Abstract

Decisions and determinants of decisions to prolong or shorten life in the course of fatal diseases like ALS are poorly understood. Decisions and desire for hastened death of N = 93 ALS patients were investigated in a prospective longitudinal approach three times in the course of 1 year. Determinants of decisions were evaluated: quality of life (QoL), depression, feeling of being a burden, physical function, social support and cognitive status. More than half of patients had a positive attitude towards life-sustaining treatments and they had a low desire for hastened death. Of those with undecided or negative attitude, 10 % changed attitudes towards life-sustaining treatments in the course of 1 year. Patients’ desire to hasten death was low and decreased significantly within 1 year despite physical function decline. Those with a high desire for hastened death decided against invasive therapeutic treatments. QoL, depression and social support were not predictors for vital decisions and remained stable. Feeling of being a burden was a predictor for decisions against life-supporting treatments. Throughout physical function loss, decisions to prolong life are flexibly adapted while desire to shorten life declines. QoL was stable and not a predictor for vital decisions, even though anticipated low QoL has been reported to be the reason to request euthanasia. In contrast, feeling of being a burden in decision making needs more attention in clinical counselling. Considering a patient’s possible adaptation processes in the course of a fatal disease is necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the course of irreversible physical decline, people are often confronted with vital decisions [1, 2]. To assist the patients’ needs and decisions in the course of a disease such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a challenging issue for physicians, caretakers and families [3].

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is one of the most devastating neurological conditions with cardinal symptoms of progressive loss of mobility and verbal communication leading to death within 3–5 years. ALS is regarded as a rare disease; nevertheless, ALS has been prominent in the debate of assisted suicide and euthanasia [23]. In Oregon, about 0.4 % of terminal cancer patients requested lethal prescriptions, whereas 5 % of ALS patients did [24]. In the Netherlands, 20 % of ALS patients die as a result of life-shortening measures like euthanasia [1, 4]. In bordering Flanders, where only one out of two euthanasia cases are officially reported, a majority of those unreported cases requested euthanasia verbally [5]. Numbers of ALS patients’ initial verbal request for physician-assisted suicide shortly after diagnosis may be as high as 56 % [6], but only a minority finally request life-shortening treatments in Oregon [4, 7, 8]. In countries like Germany [9] and Switzerland [10], the numbers for actual request of life-shortening interventions is similarly low. Therapeutic treatments with life-prolonging and quality of life-assuring effects such as non-invasive ventilation may be used more frequently in these countries [9]. Whether good palliative care and provision of therapeutic treatments antagonizes desire for hastening death has been debated [4].

Previous studies reported that patients with ALS focus on the present state in decision making rather than anticipating future progression [11]. They often seem to adopt a wait-and-see strategy regarding treatment options [12] and gradually adjust to disabilities imposed by the condition [13]. An unbiased, patient-centered view and a scientifically based knowledge of the patients’ needs are a prerequisite for good counselling [13]. Instead, doctors, caregivers, and patients alike, lack knowledge about options and patients’ preferences [14]. Furthermore, psychological defence mechanisms to explore the actual needs of patients of health care practitioners prevails [4].

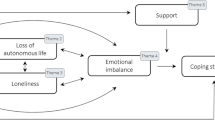

Decision making is influenced by a range of factors like individual preferences and available coping strategies [11, 15]. Quality of life may constitute a determinant of decision making in ALS and a poor quality of life is one of the most important reasons for requesting physician-assisted suicide in Oregon [8]. In the present study, we use the concept of hedonic quality of life, which refers to more transient feelings, such as life satisfaction and happiness opposed to eudaemonic health related QoL, which focuses on functioning, achievements and capabilities. The former can be measured with subjective and global quality of life which is known to be good in ALS [16, 17]. This type of QoL is not associated with loss of physical function [16, 17] and is highly underestimated by healthy persons [18]. Other possible determinants of decision making in ALS such as depression [1, 19], hopelessness [7], social support [7] and feeling of being a burden [20] have been reported by physicians and caregivers in some retrospective studies but not in others [1], whereas the presence of religious beliefs are usually determinants in patients who decide against euthanasia [1, 3]. Furthermore, cognitive impairments have been described in up to 50 % of ALS patients [21] and may interfere with decision making capabilities. The need for prospective studies to describe accurately the relationship of physical and psychological symptoms of ALS patients in the process of vital decision making is essential [4].

We report a prospective study in a large cohort of N = 93 ALS patients in advanced stages of the disease to investigate patients’ decisions and attitudes to treatments with a life-prolonging effect (non-invasive ventilation, invasive ventilation and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy) [14, 22] and desire for hastened death in the course of ALS. Furthermore, we aimed at determining factors leading to such decisions. Patients were interviewed three times within 1 year.

Methods

Design

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients were consecutively recruited at the outpatient clinic of the department of neurology at the University of Ulm and at the Charité Berlin. They were assessed three times in the course of 1 year (initial interview, 6 and 12 months later; Fig. 1). All questionnaires were presented in each interview, except the extended cognitive evaluation, which was conducted at the initial interview only. The initial interview lasted about 2–4 h, the following interviews after 6 and 12 months lasted about 1.5–3 h. Interviews were guided by a trained psychologist (S.S. or S.N.) who filled out the questionnaires.

Progression of possible determinants of decisions in the course of ALS. ALS-FRS-r ALS functional rating scale mean score; no depression, incidence of patients without clinically relevant depression; global and individual quality of life mean score; shaded area and dashed lines indicate theoretical progress of factors before our study based on clinical experience of interviewers S.S. and S.N., remaining area depicts actual study data

Participants

N = 93 ALS patients participated in this study at first interview (Table 1). Sample size was determined for a power of 80 % and α = 0.05 for medium effects (ε = 0.4) which were expected due to previous findings [15]. For the interview after 6 months (N = 43) and 12 months (N = 31), dropouts were either due to death (N = 15, equivalent to 16 % after 12 months) or physical/mental inability (N = 47, equivalent to 51 % after 12 months) to participate. Patients were diagnosed according to the El Escorial criteria (Table 1). Patients were moderately to severely impaired according to the ALS functional ratings scale (revised form, ALSFRS-R) [25]. All had been informed prior to the study regarding life-sustaining and quality of life-assuring techniques such as non-invasive ventilation (NIV), invasive ventilation via tracheostoma (IV) or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) by the treating physician.

None of the participants had any neurological or psychiatric diagnosis (other than ALS) and none used psychologically active medication.

Exclusion criteria were major cognitive impairments assessed by mini mental state examination (MMSE <22) [26]. Patients were interviewed by a certified clinical psychologist. The responsible physician confirmed that the patient had sufficient time to adapt to the diagnosis (at least 6 months). The study was approved by the ethics committees of the University of Ulm and the University of Berlin and has, therefore, been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. All participants gave informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

Decision status

A 120-item questionnaire (decision status, treatment status and determinants of decisions) regarding NIV, IV and percutaneous PEG was used (response options for decision status “decided for”, “decided against”, “undecided”, options for present treatments status “with NIV/IV/PEG” or “without NIV/IV/PEG”). Questions included “Did you seek information how to shorten life?” and “Should euthanasia be allowed?" (response options “yes” or “no”). Determinants asked about patients' “feeling of being a burden” (on a Likert scale from 1 = “not at all” to 4 = “yes indeed”).

Furthermore, the desire to hasten death was evaluated with the schedule of attitudes towards hastened death (SAHD [27]; range 0–20; >10 indicates clinically significant desire for hastened death).

Determinants of decision

Quality of life and depression

Global quality of life (QoL) was assessed with the anamnestic comparative self-assessment (ACSA [28]; range −5 for as bad as possible and +5 as good as possible), subjective QoL was assessed with the schedule for the evaluation of subjective quality of life (SEIQoL [29]; range 0 for as bad as possible and 100 as good as possible). Depression was measured with the Allgemeine Depressionsskala (ADSK [30]; German version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, CES-D, range 0–60; threshold >16).

Social support

Perceived social support was evaluated with the emotional scale of the social support scale (Soziale Unterstützungsskala SOZU K 22 [31]; 5-point Likert scale range from 1 = 'not at all' to 5 = 'yes indeed').

Cognition

Cognitive performance was assessed with explorative interview and MMSE [26] (range 0–30, threshold <26 for mild dementia).

Additionally, at first interview in N = 58 ALS patients verbal fluency was assessed with the Regensburg fluency test (Regensburger Wortflüssigkeitstest) [32], attention and frontal inhibition was assessed with a version free of motor requirements of the D2-test [33] (in-house computer adaptation) [34].

Statistics

Repeated measures ANOVA with time as factor was performed separately for independent variables, “desire for decisions for life-prolonging treatments (PEG/NIV/IV)” and “desire for hastened death (SAHD)”; and dependent variables, physical function (ALS-FRS-r), quality of life (SEIQoL, ACSA), depression (ADSK), social support (SOZU); and the factor “feeling of being a burden”.

Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA was performed for decisions for life-prolonging treatments (PEG/NIV/IV) and dependent variable physical disability (ALS-FRS-r), age, quality of life (SEIQoL, ACSA), depression (ADSK), social support (SOZU) and the factor “feeling of being a burden”.

Using multivariate logistic regression, we examined which variables predicted desire for hastened death. Variables were psychological determinants such as quality of life (ACSA, SEIQoL), depression (ADSK) and feeling to be a burden as well as external determinants such as physical function (ALS-FRS-r), age and social support (SOZU). Only participants with complete data sets were included. As data were frequently not normally distributed, non-parametric statistics were used.

The statistical analysis was performed with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 16.0. The significance level was adjusted two-tailed at p = 0.05.

Results

Vital decisions

Initially, up to half of the patients decided on life-sustaining treatment. About half were undecided (Table 2).

Of those with undecided or negative attitudes, there was a significant increase in decisions for IV and PEG towards acceptance in the course of 1 year. For NIV the increase was not significant.

The desire for hastened death was low (Fig. 3) and decreased during the first 6 months (F = 6.72, p = 0.01*). It remained low throughout the study despite the fact that physical function declined (Table 2; Fig. 2). None of the other possible determinants of decision (QoL, depression, social support, feeling of being a burden) changed significantly in the course of a year (Fig. 2). Indicators of psychosocial adaptation such as high subjective quality of life (SEIQoL score >70 on a scale of 100 indicates a good QoL), and neutral to positive global quality of life (ACSA) and low depression (ADSK) were stable throughout the study (Table 2; Fig. 2).

About one-third of the patients (N = 35) responded “yes” for the item “Did you seek information how to shorten life?” and more than two-thirds (N = 63) responded “yes” for the item “Should euthanasia be allowed?"

Determinants of decisions

Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA was performed for decisions for life-prolonging treatments and actual treatment choices (PEG/NIV/IV) and determinants (psychological, external and desire for hastened death).

Psychological determinants

Subjective and global quality of life and depression were not significantly different between patients who decided for life-prolonging decisions (NIV/IV/PEG) and those who decided against. The variable “feeling of being a burden” was significantly different between patients who decided for NIV, PEG and IV (trend) compared to those who decided against those treatments (Table 3).

QoL and depression were no significant predictors for desire for hastened death.

The variable “feeling of being a burden” was a significant predictor for desire for hastened death (F = 16.22, p < 0.001).

External determinants: physical disability, age, social support

Physical disabilities were significantly predominant in patients who decided for NIV and for PEG but not for IV compared to those patients who decided against (Table 3).

Physical disabilities were not significant predictors for desire for hastened death.

Neither age nor perceived social support were predictors for decisions towards life-sustaining treatments nor for the desire for hastened death.

Determinants and actual treatment choices

Physical disabilities were significantly different between people with ventilation and PEG, and those without.

Patients with ventilation and PEG had a significantly higher “feeling of being a burden” compared to those without. The other determinants were not different between groups (Table 3).

Desire for hastened death and actual treatment choices

Desire for hastened death and decisions for invasive life-prolonging treatments (IV/PEG) were negatively associated: Those who decided for life-prolonging treatments (IV/PEG) had a significantly lower desire for hastened death than those who decided against. Desire for hastened death and decisions for NIV were not associated (Table 3).

Discussion

Decisions

The present study is the first prospective study on decisions to prolong or shorten life in a large population of ALS patients. ALS patients showed no end-of-life-oriented despair but decided for life-sustaining treatments indicating positive attitudes towards life. Half of the patients expressed the explicit desire for non-invasive life-prolonging treatments even at the initial interview. In the course of 1 year, there was a significantly increasing number of patients deciding for invasive life-prolonging treatments (IV/PEG), particularly in those patients who had previously either negative or undecided attitudes towards life-prolonging treatments. This illustrates the “wait-and-see” strategy [11, 12] of ALS patients as they adapt and adjust their preferences concerning requests of invasive treatments. Those who decided for invasive life-prolonging treatments had a significantly lower desire for hastened death than those who decided against. Therefore, decisions for invasive life-sustaining treatments antagonize desire to shorten life or vice versa [4].

Patients had no desire for hastened death and it declined even more in the course of ALS progression despite physical function decline. It was far below the threshold for clinically relevant desire for hastened death [27]. About two-thirds of the patients thought that euthanasia should be allowed. One-third of the patients actively searched for information on how to shorten life. But when physical disabilities progress, patients still value life, and only a small percentage of patients consider life-shortening treatments [4, 8–10, 19]. In other regions, e.g. in the Netherlands, up to 20 % of ALS patients request life-shortening treatments [3]. These numbers are incompatible with patients’ attitudes and decisions to end life in the present study and other studies in different regions [4, 10].

Determinants of decision

Quality of life and depression were not determinants for decisions for life-prolonging treatments nor for the desire to shorten life. The lack of an association between depression and requests for life-shortening treatments is in line with previous studies [1, 7, 8]. For QoL, this lack of association has not been shown before. An anticipated poor quality of life was one of the most important reasons for requesting physician-assisted suicide in Oregon [8] and probably in other locations as well. Yet, our prospective data do not support that low QoL is prevalent or predictive. Hedonic QoL was good and depression was low and stable throughout the study despite significant decrease in physical function [16, 17, 35]. A drop in quality of life and increase in depression may follow the diagnosis but after a few months a majority of patients achieve equilibrium, as our data suggest. Differences in QoL between patients are likely due to pre-existing individual differences [36].

We found the “feeling of being a burden” to be a significant determinant of decision against life-prolonging treatment and for the desire to hasten death. Furthermore, those patients with ventilation and/or PEG had a significantly stronger “feeling of being a burden” than those without. The issue of “feeling to be burden” seems to be predominant in patients with terminal illness [37] and this is the first prospective data providing evidence for the association of vital decision making and “feeling of being a burden” in a large cohort of ALS patients. In Maessen’s [1] retrospective study, caregivers did not report this item to be important in the case of deceased ALS patients but in Oregon, terminally ill patients (including six ALS patients) in favour of assisted suicide reported great distress due to the feeling of being a burden [7, 8]. In an environment in which proper physical (and cognitive) functioning is requested for social inclusion, people with disability and terminal illness are prone to experience themselves as being a burden because they do not fulfill these requirements.

Physical disabilities determined the desire for therapeutic treatments, meaning that the more patients were advanced in their disease, the higher the probability to ask for NIV and PEG. NIV is an established procedure that is regularly used in the early course of the disease [22]. PEG seems to have similar therapeutic implications [38], whereas for IV the determinants of decisions are more heterogeneous. Ventilated patients and/or with PEG had the same QoL and depression rate as non-ventilated patients and/or those without PEG. Thus, in line with previous results [17], ventilated patients experience a satisfying quality of life and are not depressed [39]. This is also true for patients with PEG. Cognitive impairments were excluded and did not account for any differences or lack of differences between groups. Therefore, the satisfactory QoL in patients with NIV/IV and/or PEG compared to those without is not a function of incapability to comprehend the impact of the diagnosis but rather a result of the adaptation processes.

Concerning the desire of hastened death, external factors like loss of physical functioning [40], age [1] and perceived social support were not predictors. This supports the notion that lack of social support is not necessarily relevant for the desire to shorten life [8] and the desire to shorten life does not increase while physical function declines or age increases [1]. As opposed to positive attitudes for life-prolonging treatments, which increased in the course of physical function decline, desire to hasten death and physical disabilities both declined in the course of ALS.

Conclusion

These data suggest that patients change their attitudes positively towards life and learn to cope with the disease [15]. Decisions are adapted accordingly. Possible determinants of decisions like QoL, depression and perceived social support are stable. Quality of life is not a determinant of negative or positive decisions and it is high in patients with invasive life-prolonging treatments. The “feeling of being a burden” is a predominant issue in ALS patients in decisions against life and needs to be specifically addressed in clinical counselling.

The data may enable clinicians and caretakers to best support patients in their decision making process. Hastened death decisions [8, 10] have to be circumvented by considering patient’s possible adaptation processes in the course of a fatal disease.

References

Maessen M, Veldink JH, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, de Vries JM, Wokke JH, van der Wal G, van den Berg LH (2009) Trends and determinants of end-of-life practices in ALS in the Netherlands. Neurology 73(12):954–961

Oliver DJ, Turner MR (2010) Some difficult decisions in ALS/MaND. Amyotroph Later Scler 11(4):339–343

Veldink JH, Wokke JH, van der Wal G, Vianney de Jong JM, van den Berg LH (2002) Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide among patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in The Netherlands. N Engl J Med 346:1638–1644

Ganzini L, Block S (2002) Physician-assisted death—a last resort? N Engl J Med 346:1663–1665

Smets T, Bilsen J, Cohen J, Rurup ML, Mortier F, Deliens L (2010) Reporting of euthanasia in medical practice in Flanders, Belgium: cross sectional analysis of reported and unreported cases. BMJ 341:c5174

Ganzini L, Johnston WS, Mcfarland BH, Tolle SW, Lee MA (1998) Attitudes of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and their care givers toward assisted suicide. N Engl J Med 339:967–973

Ganzini L, Silveira MJ, Johnston WS (2002) Predictors and correlates of interest in assisted suicide in the final month of life among ALS patients in Oregon and Washington. J Pain Symptom Manage 24(3):312–317

Ganzini L, Goy ER, Dobscha SK (2009) Oregonians’ reasons for requesting physician aid in dying. Arch Intern Med 169(5):489–492

Kühnlein P, Kübler A, Raubold S, Worell M, Kurt A, Gdynia HJ, Sperfeld AD, Ludolph AC (2008) Palliative care and circumstances of dying in German ALS patients using non-invasive ventilation. Amyotroph Later Scler 9:91–98

Stutzki R, Schneider U, Reiter-Theil S, Weber M (2012) Attitudes toward assisted suicide and life-prolonging measures in Swiss ALS patients and their caregivers. Front Psychol 3:443

Hogden A, Greenfield D, Nugus P, Kiernan MC (2012) What influences patient decision-making in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis multidisciplinary care? A study of patient perspectives. Patient Prefer Adherence 6:819–838

Burchardi N, Rauprich O, Hecht M, Beck M, Vollmann J (2005) Discussing living wills. A qualitative study of a German sample of neurologists and ALS patients. J Neurol Sci 237(1–2):67–74

Robinson EM, Phipps M, Purtilo RB, Tsoumas A, Hamel-Nardozzi M (2006) Complexities in decision making for persons with disabilities nearing end of life. Top Stroke Rehabil 13(4):54–67

Bach JR (2003) Threats to ”informed” advance directives for the severely physically challenged? Arch Phys Med Rehabil 84(4:2):23–28

Matuz T, Birbaumer N, Hautzinger M, Kübler A (2010) Coping with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: an integrative view. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 81(8):893–898

Kübler A, Winter S, Ludolph AC, Hautzinger M, Birbaumer N (2005) Severity of depressive symptoms and quality of life in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 19:182–193

Lulé D, Häcker S, Ludolph A, Birbaumer N, Kübler A (2008) Depression and quality of life in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Dtsch Arztebl Int 105(23):397–403

Lulé D, Ehlich B, Lang D, Sorg S, Heimrath J, Kübler A, Birbaumer N, Ludolph AC (2013) Quality of life in fatal disease: the flawed judgement of the social environment. J Neurol 260(11):2836–2843

Ganzini L, Goy ER, Dobscha SK (2008) Prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients requesting physicians’ aid in dying: cross sectional survey. BMJ 337:a1682

Singer PA, Martin DK, Kelner M (1999) Quality end-of-life care: patients’ perspectives. JAMA 281:163–168

Phukan J, Elamin M, Bede P, Jordan N, Gallagher L, Byrne S, Lynch C, Pender N, Hardiman O (2012) The syndrome of cognitive impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a population-based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 83(1):102–108

Gordon PH, Salachas F, Lacomblez L, Le Forestier N, Pradat PF, Bruneteau G, Elbaz A, Meininger V (2012) Predicting survival of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis at presentation: a 15-year experience. Neurodegener Dis 12(2):81–90

Rowland LP, Shneider NA (2001) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N Engl J Med 344:1688–1700

Sullivan AD, Hedberg K, Fleming DW (2000) Legalized physician-assisted suicide in Oregon—the second year. N Engl J Med 342:598–604

Cedarbaum JM, Stambler N, Malta E, Fuller C, Hilt D, Thurmond B, Nakanishi A (1999) The ALSFRS-R: a revised ALS functional rating scale that incorporates assessments of respiratory function. BDNF ALS Study Group (Phase III). J Neurol Sci 169(1–2):13–21

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) Mini-mental state (a practical method for grading the state of patients for the clinician). J Psychiatr Res 12:189–198

Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, Stein K, Funesti-Esch J, Kaim M, Krivo S, Galietta M (1999) Measuring desire for death among the medically ill: the schedule of attitudes toward hastened death. Am J Psychiatry 156:94–100

Bernheim JL (1999) How to get serious answers to the serious question: ‘How have you been?’: subjective quality of life (QOL) as an individual experiential emergent construct. Bioethics 13:272–287

Hickey AM, Bury G, O’Boyle CA, Bradley F, O’Kelly FD, Shannon W (1996) A new short form individual quality of life measure (SEIQoL-DW): application in a cohort of individuals with HIV/AIDS. BMJ 313:29–33

Hautzinger M, Bailer M, Hofmeister D, Keller F (2012) ADS—Allgemeine Depressionsskala., Tests infoHogrefe, Göttingen

Fydrich T, Sommer G, Tydecks T, Brähler E (2009) Fragebogen zur sozialen Unterstützung (F-SozU): Normierung der Kurzform (K-14)Social Support Questionnaire (F-SozU): Standardization of short form (K-14). Z Med Psychol 18:1

Aschenbrenner A, Tucha O, Lange K (1999) RWT Regensburger Wortflüssigkeits-test., HandanweisungHogrefe, Göttingen

Brickenkamp R (1962) Aufmerskamkeits-Belastungs-Test (d2). Hogrefe, Göttingen

Lulé D, Heizmann C, Sorg S, Ludolph AC (2010) With the blink of an eye: d2 attention test in the severely paralysed. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 11(1):143–149

Robbins R, Simmons Z, Bremer B, Walsh S, Fischer S (2001) Quality of life in ALS is maintained as physical function declines. Neurology 56:442–444

Roach AR, Averill AJ, Segerstrom SC, Kasarskis EJ (2009) The dynamics of quality of life in ALS patients and caregivers. Ann Behav Med 37(2):197–206

Czell D, Bauer M, Binek J, Schocjh OD, Weber M (2013) Outcome of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy insertion in respiratory impaired amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients under non-invasive ventilation. Respir Care 58(5):838–844

Johnson JO, Sulmasy DP, Nolan MT (2007) Patients’ experiences of being a burden on family in terminal illness. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 9(5):264–269

McDonald ER, Hillel A, Wiedenfeld S (1996) Evaluation of the psychological status of ventilatory-supported patients with ALS/MND. Palliat Med 10:35–41

Munroe CA, Sirdofsky MD, Kuru T, Anderson ED (2007) End-of-life decision making in 42 patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Respir Care 52(8):996–999

Acknowledgments

This is an EU Joint Programme—Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND) project. The project is supported through the following organisations under the aegis of JPND—http://www.jpnd.eu e.g. Germany, Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF, FKZ), Sweden, Vetenskaprådet Sverige, and Poland, Narodowe Centrum Badán i Rozwoju (NCBR). This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG 336/13-2 und BI 195/54-2) and the (BMBF #01GQ0831 and BMBF #01GM1103A).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lulé, D., Nonnenmacher, S., Sorg, S. et al. Live and let die: existential decision processes in a fatal disease. J Neurol 261, 518–525 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-013-7229-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-013-7229-z