Abstract

Injuries resulting from blows with beer steins are a frequent occurrence during annual autumn fairs or at beer halls in South Germany and Austria. The majority of these cases are tried in court and thus being assessed by a forensic medicine expert. The article at hand gives a short overview on the injury potential of one-litre beer steins and explains the key variables to consider when analyzing beer stein injuries. On the basis of representative cases, which were assessed by specialists from the Institute of Legal Medicine of the Munich University over the last 5 years, the main biomechanical aspects and resulting injuries of one-litre beer stein assaults are discussed. Several severe and potentially life-threatening injuries have been observed after an assault with a one-litre beer stein. There is a discrepancy between the mechanical stability of brand new and used steins and the corresponding injuries, which can be explained by a decrease in impact tolerance of the steins with their use. In general, a blow with a one-litre glass or stonework beer stein to the head can cause severe and even life-threatening blunt as well as sharp trauma injuries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

One-litre beer steins are an inherent part of (beer) culture in southern Germany and parts of Austria. This special drinking vessel, which is made of glass or stonework not only brings joy to millions of people. There are more than five million Oktoberfest visitors every year in addition to the many smaller annual autumn fairs in south Germany and Austria. One-litre steins are also used in many regional restaurants throughout the whole year. These drinking vessels can cause severe or even lethal injuries, when misused as a weapon. The aim of this article is to give a short overview on the injury potential of beer stains and the key variables to consider when analyzing a particular situation from a forensic biomechanical standpoint. On top of that, a few cases from the archive of the Institute of Legal Medicine of the Munich University will be presented, which clearly demonstrate the wide range of injury outcomes that can result from the interaction between a one-litre stein and the human body.

Empirical data

There is no comprehensive data source regarding the use of beer steins and/or other drinking glasses as weapons. Since 2011, the city of Munich and/or its police headquarters have been publishing the number of assaults committed with a beer stein during the annual Oktoberfest. The police registered a rather stable number of cases ranging from 34 to 69 each year and constituting 9 to 16% of all documented criminal assaults during this event [1,2,3,4,5].

The search in the archive of the Institute of Legal Medicine in Munich (covering large parts of south Bavaria with approximately seven million inhabitants) revealed a total of 42 cases involving the usage of a one-litre beer stein as a weapon over a 5-year period (2012–2016). In this context, it is remarkable that during the same time interval, only 4 cases could be found in the archive in which a smaller stein (0.5 l) was used.

For the time span between 2004 and 2010, 31 cases with expert witness testimonies by the employees of our Institute were reported [6]. Seven victims suffered a bony lesion and three times an impression fracture of the skull occurred, which had to be treated surgically.

Giving the nature of circumstances, it is very difficult, if not impossible, to obtain reliable information regarding the details of each assault. Not only the participants, but also the witnesses are frequently drunk and their statements of the event have very little common ground. Because of that, only the typical “probable” features of such incidents can be described and evaluated in a forensic biomechanical assessment. Most of the assailants and victims are males, the typical assault consists of a single blow with the stein to the head (in 8 cases out of the total 42 a throw of the one-litre stein was described instead of a blow, in one case only more than two blows were indicated). In two cases, an assault was described in which the stein was initially broken and used primarily for stabbing.

The most common injuries resulting from assaults with a one-litre stein in the above sample group of 42 cases were skin lacerations (present in 30 cases). It is frequently difficult to objectively ascertain their causation by blunt or sharp violence from the available data. However, in cases with one reported blow and multiple wounds it is evident that most of the injuries must have been caused by glass (or stonework) fragments. Bony injuries were not very frequent. In 5 cases, the victims suffered at least one fracture (all of them in the face region) and in 2 cases one or more broken teeth were documented.

The diversity of the injury outcomes resulting from an assault with a one-litre beer stein (made of glass) can be demonstrated by the following cases (from the archives of the Institute of Legal Medicine of the LMU Munich, not limited to the years 2012–2016):

A 42-year-old female victim was hit at the left side of the head by a thrown beer stein at the Oktoberfest and immediately bled from the left ear. The patient was adequately responsive at any point of time and displayed a left temporal skin laceration. A CT-scan showed a left parietal skull fracture with an adjacent epidural haematoma (maximum width 6 mm) and a left petrous bone fracture affecting the left temporo-mandibular joint. An otorhinolaryngologist found a haematotympanon and a hypacusis on the left side, the tympanic membrane was intact. The treatment was conservative.

A 33-year-old male victim was hit twice by a beer stein to the head and suffered two skin lacerations at the right parietal region. The performed CT-diagnostics revealed an impression fracture (4 to 5 mm) of the right parietal bone, which was not accompanied by an intracranial haemorrhagee. The impressed fragment (size approx. 2 × 3 cm, with multiple fractures) was surgically removed.

A 19-year-old male victim was hit with a beer stain in the face. The diagnostics incl. CT-scans revealed multiple skin lacerations in the left temporal and orbital region incl. both the upper and the lower eyelid, a penetration injury of the left eyeball with a leakage of the intraocular substance and a prolapse of the iris, an active bleeding from the A. angularis and two foreign objects (glass shards) within the soft tissue of the left eye cavity. It is to note that the only known witness described a blow with a beer stain whereas the assailant stated that he hit the victim with a wine glass instead.

During a brawl between two groups of young males, one suspect picked up a glass shard from a broken beer stein and stabbed the 24-year-old victim to the chest. The victim suffered two wounds in the anterior thorax region, one of which penetrated the left chest cavity and caused a haematopneumothorax. No organ injury was documented.

A 24-year-old male victim was hit at the left side of his head by a thrown beer stein. The stein broke into several pieces when it hit the head. The injuries were limited to three small skin lacerations in the left occipital region.

To the authors’ knowledge, there is not a single assault case with a beer stein, which ultimately caused the death of the victim. However, we can report one lethal accident with a glass stein:

A 54-year-old man was found at his workplace, a big hotel kitchen, in a large pool of blood, in a half-seated position with his neck just above the shards of a one-litre beer stein made of glass lying on the ground. He showed one skin laceration in the right eyebrow region (with a glass fragment found in the wound) and another deep wound in the right neck region. The M. sternocleidomastoideus, the V. jugularis interna were completely severed and the A. carotis communis partially severed, the fifth cervical vertebra showed a serrated defect. According to the autopsy result, the man bled to death. Based on the analysis of all ascertained traces, the most probable cause of the lethal injuries was assumed a slip/trip and a fall of the victim with the stein held in one hand and an interaction of his face and neck with stein fragments during the landing.

Basic physical properties of beer steins

The typical one-litre beer stein is made of glass and has a mass of approx. 1.3 kg. The steins made of stonework show a higher degree of variability regarding the mass; we registered weights in the range of 1.05 up to 1.27 kg. The typical shape and material thickness of the steins are visualized in CT-scans (Figs. 1 and 2). Both materials are virtually non-deformable. The handle, which is positioned in the midsection of the beer mug, attached approximately at the upper and lower third, makes the usage of the stein (both for drinking and striking) easy.

Forensic biomechanical considerations

When used as a striking tool, the biomechanical load of a one-litre beer stein imposed on the victim depends on the intensity of the strike. The single most important parameter is the impact velocity of the stein (in most cases the head of the victim does not contribute to the impact velocity to a relevant extent). The impact velocity depends on the ability of the assailant to strike (or throw) and on his motivation (i.e. how much of his potential he is actually using to accelerate the stein towards the head). In order to get basic information about the order of magnitude of the velocities that can be reached when striking with a stein, we performed lab measurements with two “average” male volunteers (both approx. 177 cm and 84 kg) without special training (no professional experience in boxing, sports involving throwing or similar). With a one-litre stein (1270 g), held at the handle and accelerated in an overhead movement (striking in a hammer-like manner), they achieved comparable maximum velocities of up to 12.5 ms−1 (45 kph). As expected, the lighter half-litre stein (688 g) could be swung even faster (up to 15.5 ms−1 for one and 16.5 ms−1 for the other volunteer). The velocity was measured approximately at breast height of the volunteers (120 cm above the ground; this corresponds roughly to the head position of a person sitting on a typical beer bank).

During the first phase of the contact between the stein and the skull, the impact force summons and is then transferred onto the target area. For the assessment of injury risk, the relation between the impact tolerance of the head (i.e. the skull) and the impact strength of the stein is essential. If the stein is the first to break, the impact force cannot rise anymore and no (further) blunt skull trauma is to be expected. If, on the other hand, the impact strength of the stein exceeds the one of the skull, fractures and associated (maybe even lethal) injuries can occur.

Given the physical properties of the one-litre stein, it is possible to produce a strike that has the potential to cause severe head trauma (traumatic brain injury). In physical terms, a sufficient momentum can be produced (the product of the mass and the velocity of the stein moving towards the victim’s head). The biomechanical impact tolerance of the human head has been studied extensively. The minimum impact force leading to fractures in different skull regions has been reported to be less than 1 kN for the nasal and some other facial bones, approx. 3–6 kN for the temporo-parietal region and approx. 10–12 kN for the occipital area of the head [7,8,9,10,11,12]. In this context, it needs to be pointed out that the biomechanical tolerance exhibits a high degree of interindividual variability and that the only way to assess such individual tolerance in a specific case would be lab testing of the person at hand.

Assessment of mechanical stability of the steins

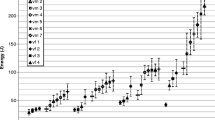

In order to ascertain the force level at which one-litre steins of glass brake, we performed a series of lab measurements. As a human head surrogate, we used the aluminium core of the Hybrid III crash-test dummy head that was covered by a layer of silicon (Deguform—additive-curing silicone duplicating compound, thickness 0.8–1.0 cm). The dummy head was placed on a KISTLER force plate recording the reaction force in all three dimensions at 5000 Hz. A motion analysis system (Motion Analysis Corp., Santa Rosa, CA, USA) with the Cortex software was used along with 12 Eagle cameras. A recording frequency of 500 Hz was used. The 3D motion of a marker placed on the stein opposite to the handle was recorded, and the velocity of the marker was calculated. The impact velocity was defined as the mean velocity over the last five frames (0.01 s) prior to the contact to the dummy head. A single male volunteer (38 years, 176 cm, 84 kg) carried out strikes with either the side or the bottom of the one-litre stein held at the handle. In the first series of measurements, a set of brand new steins was used. The first strike was performed quite lightly. If the stein did not brake, another strike in the same constellation was performed with (subjectively) higher impact intensity. This procedure was repeated until the stein broke or the measured maximum force exceeded 10 kN. This force level was set for the sake of the volunteer’s safety and the safety of the equipment (the force plate is designed to measure forces up to 10 kN). The force level of 10 kN is sufficiently high to assume that a skull fracture would be possible.

A total number of 44 strikes were performed with the brand new steins. At first, 34 strikes with the side of each stein were performed as described above. As seen in Table 1, only two of the new steins broke, all the rest withstood forces above 10 kN without breaking apart.

When striking with the bottom, none of the steins broke, even though the maximum force exceeded the level of 10 kN in every single case.

The results of the measurements performed with brand new glass steins suggest a very high mechanical stability of the glass steins, higher than the one of the skull (especially the typical target regions in stein assaults—the face, the frontal and the temporo-parietal regions). This is contradictory to the above presented empirical data with relatively few bony lesions and multiple wounds caused by sharp violence (that are consistent with breaking of the stein). This phenomenon can only be explained by a reduced mechanical stability of used (microfractured) steins. In order to verify this hypothesis, which was also suggested in the literature [13], a new set of measurements was performed with used glass steins. A total number of 18 steins were obtained from one of the beer tent operators at the Oktoberfest. While we were assured that each of the steins was used multiple times, no visible signs of mechanical damage to the steins were present. On the one hand, 13 of the used steins were hit with their side using the exact same protocol as described above. As can be seen in Table 2, all of the used steins broke before the predefined maximum value of 10 kN was reached. The measured forces ranged between 2.8 and 7.0 kN and was thus substantially lower than the predefined maximum of 10 kN. A total number of 10 steins were used for strikes with the bottom. Seven of the steins broke, while the remaining three withstood forces of 10 kN without breaking apart (lower part of Table 2). Since these three steins still did not show any sign of mechanical damage, they were used again for testing their stability in side impacts as seen in Table 2.

In order to compare the baseline mechanical stability of stonework and glass steins, a third set of lab tests was performed. The only difference in the test setup was the method of velocity measurement—instead of the Motion Analysis System, an Olympus® i-Speed 3 high-speed camera was used at 2000 Hz. Using six brand new one-litre stonework steins (as depicted in Fig. 1), the results summarized in Table 3 were achieved. All three steins of the side impact experiment and two out of the three bottom impacts broke. The measured maximum impact forces ranged from 5.3 to 7.2 kN in the side impacts and from 3.9 kN to above 10 kN in bottom impacts.

Discussion

The lab test results show that brand new steins have a high degree of mechanical stability. Typically, they do not brake at force levels reported as necessary for the production of skull fractures. However, with use the steins can become more fragile and thus can break on impact to the head without causing skull fracture (a scenario mostly observed in assault cases).

From a forensic biomechanical point of view, it is essential to note that there is no way of establishing the state and/or age of the stein optically or otherwise. In other words, an assailant holding a stein cannot know whether it is new or not.

The wall thickness of one-litre beer glass steins is approximately two times higher than the one reported for beer bottles (2–3.6 mm, [14]) and thus it is obvious that the amount of blunt force that can be delivered by using one-litre beer steins to the head is potentially significantly higher.

A forcefully performed strike to the head with the side and especially the even more mechanically robust bottom of an one-litre stein (made of glass or clay) can lead to serious blunt force head injuries such as skull fractures and associated complications (intracerebral bleeding etc.). The thicker bottom region is more solid and strikes with the bottom thus more dangerous with regards to blunt force trauma. The impact forces measured in strikes that did not lead to stein damages were found in the region of (or above) the biomechanical tolerance of the skull. Interestingly, in test series with the same stein, the maximum force measured in the experiments with stein damages lay consistently below the highest values for tests without stein breakage. This phenomenon might contribute to rather mild (limited to the skin) blunt force injuries in cases with breaking of the stein. Of course, it cannot be reasoned that a massive strike is “safer” because of this registered force reduction (in case the stein is stable enough, the risk of skull fracture increases with a rising velocity and thus intensity).

It should be noted that apart from the primary injuries, the sequelae of a possible uncontrolled fall to the ground can be life-threatening. This hazard is relevant, especially as most of the victims are alcohol-intoxicated.

Even though no cases of an actual fatal outcome of an assault with a one-litre beer stein are known to the authors, serious injuries resulting from both blunt and sharp violence occurred that clearly have the potential to put the victim’s life at risk.

In the experiments, we could not observe any characteristic patterns regarding the number, size and shape of fragments resulting from a broken glass stein and the dummy head. The only consistent observable fact was that the upper part of the stein stayed intact in a crown-like form (see Fig. 3) in several cases after an impact with the bottom of the stein and never after an impact with the side. Thus, a preserved upper ring frame of the stein suggests an impact with its bottom. In our study with smaller (0.5 l) stonework steins some more basic regularity was observable [15, 16]. It is notable that the fragments of the broken stein can spread to a considerable distance from the point of impact. Superficial skin injuries caused by glass shards at distances of up to 2 m from the impact location appear possible.

Limitations

The number of tested steins is limited and the cut-off level of maximum force at 10 kN makes a statistical analysis impossible. However, the results are very convincing and while we cannot offer valid data regarding the values of stein stability, the conclusions relevant from the point of forensic biomechanics appear fully justified.

In order to ensure the highest possible proximity to real-world situations, the impact constellation was not standardized; the strikes were performed by a volunteer.

Conclusions

A blow with a one-litre stein made of glass or stonework to the head can lead to severe and even life-threatening injuries. The discrepancy between the high mechanical stability of brand new steins compared to the human skull and the relatively small number of skull (and associated intracranial) injuries resulting from assaults with one-litre steins can be explained by a decrease in impact tolerance of the steins with their use.

In case the beer stein fractures (due to the impact on the head), the remaining stump with its sharp-edged margins as well as other fragments might turn into a sharp instrument that can cause severe injuries.

Severe and potentially life-threatening injuries have been observed after an assault with a one-litre beer stein.

References

Sicherheitsreport 2013. Polizeipräsidium München. Access via internet www.polizei.bayern.de (15.09.2017)

Sicherheitsreport 2014. Polizeipräsidium München. Access via internet www.polizei.bayern.de (15.09.2017)

Sicherheitsreport 2015. Polizeipräsidium München. Access via internet www.polizei.bayern.de (15.09.2017)

Sicherheitsreport 2016. Polizeipräsidium München. Access via internet www.polizei.bayern.de (15.09.2017)

Das 179. Münchner Oktoberfest. Münchner Statistik, 2. Quartalsheft, Jahrgang 2013. Statistisches Amt der Landeshauptstadt München. Access via internet https://www.muenchen.de/rathaus/dam/jcr:6b201efa-12fb-4539.../mb13201.pdf (15.09.2017)

Dorfner P (2014). Analyse von Maßkrugschlägen hinsichtlich potentiell lebensgefährlicher Verletzungen. Dissertation, Ludwig-Maximilian University Munich

Cormier J, Manoogian S, Bisplinghoff J, Rowson S, SantagoA MNC, Duma S (2010) Ann Adv Automot Med 54:3–14

Nahum AM, Gatts CW, Danforth JP (1968). Impact tolerance of the skull. Proc 12th Stapp car crash conference: 302-317

Allsop D, Perl R, Warner C (1991). Force/deflection and fracture characteristics of the temporo-parietal region of the human head. Proc 35th Stapp car crash conference: 269-278

Schneider DC, Nahum AM (1972). Impact studies of facial bones and skull. Proc 16th Stapp car crash conference: 186-203

Nyquist GW, Cavanaugh JM, Goldberg SJ, King AI (1986). Facial impact tolerance and response. Proc 30th Stapp car crash conference: 379-400

Yoganandan N, Pintar F (2004) Biomechanics of temporo-parietal skull fracture. Clin Biomech 19:225–239

Sheperd JP, Huggett RH, Kidner G (1993) Impact resistance of bar glasses. J Trauma 35(6):936–938

Bolliger SA, Ross S, Oesterhelweg L, Thali MJ, Kneubuehl BP (2009) Are full or empty beer bottles sturdier and does their fracture-threshold suffice to break the human skull? J Forensic Legal Med 16(3):138–142

Kunz SN, Tutsch-Bauer E, Graw M, Adamec J (2016) Blows to the skull with a beer stein. Biomechanical aspects of a 0.5l beer stein as a striking weapon. Rechtsmedizin 26(3):189–196

Kunz SN, Lochner S, Bedacht M, Adamec J (2016) Specific biomechanical aspects of a beermug injury. Kriminalistik 2:87–93

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Adamec, J., Dorfner, P., Graw, M. et al. Injury potential of one-litre beer steins. Int J Legal Med 133, 1075–1081 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-018-1803-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-018-1803-y