Abstract

Requisite to routine casework involving unidentified skeletal remains is the formulation of an accurate biological profile, including sex estimation. Choice of method(s) is invariably related to preservation and by association, available bones. It is vital that the method applied affords statistical quantification of accuracy rates and predictive confidence so that evidentiary requirements for legal submission are satisfied. Achieving the latter necessitates the application of contemporary population-specific standards. This study examines skeletal pelvic dimorphism in contemporary Western Australian individuals to quantify the accuracy of using pelvic measurements to estimate sex and to formulate a series of morphometric standards. The sample comprises pelvic multi-slice computer tomography (MSCT) scans from 200 male and 200 female adults. Following 3D rendering, the 3D coordinates of 24 landmarks are acquired using OsiriX® (v.4.1.1) with 12 inter-landmark linear measurements and two angles acquired using MorphDb. Measurements are analysed using basic descriptive statistics and discriminant functions analyses employing jackknife validation of classification results. All except two linear measurements are dimorphic with sex differences explaining up to 65 % of sample variance. Transverse pelvic outlet and subpubic angle contribute most significantly to sex discrimination with accuracy rates between 100 % (complete pelvis—10 variables) and 81.2 % (ischial length). This study represents the initial forensic research into pelvic sexual dimorphism in a Western Australian population. Given these methods, we conclude that this highly dimorphic bone can be used to classify sex with a high degree of expected accuracy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In routine and nontraditional investigations, a forensic anthropologist draws upon an intimate and specialized knowledge of human anatomy and osteology complemented by established morphoscopic (visual—observational) and morphometric (linear—measurement) standards. Those standards are used to identify biological attributes in the skeleton, such as (but not limited to) basic differences between sex and age-related landmarks. In satisfying requirements for legal admissibility, morphometric approaches have a robust statistical foundation readily accepted when appropriate contemporary population-specific standards are applied. Geographically and genetically isolated human groups, however, display population-specific skeletal characteristics, many of which are evident in the relative expression and magnitude of sexually dimorphic features [1, 2].

For the forensic practitioner, the latter is an important consideration in selecting appropriate anthropological standards, especially as it is well established that the application of non-population-specific standards (e.g. for estimating sex) results in a reduction in classification accuracy [3–5]. Another important consideration concerns the representativeness of available anthropological standards. Repositories of documented human skeletons have traditionally provided the necessary biological data for the development of population-specific standards. Those repositories, however, represent a chronological ‘snapshot’ of a given population at an earlier time. Populations are not ‘stagnant’, and skeletal morphological variations continually arise due to secular trends and increasing ethnic admixture due to global migration [4, 6].

For forensic practice in Western Australia and Australia, in general, there is a paucity of contemporary population-specific morphometric skeletal standards, largely due to the unavailability of the required sources of biological data for their development, e.g. contemporary documented skeletal collections. Recent research has established that the virtual analysis of medical imaging modalities offer an appropriate, reliable and arguably more representative source of contemporary population-specific data from which skeletal standards can be developed [7–10]. This latter approach is essential in countries that do not have access to, or a capacity to build, contemporary skeletal collections representative of their modern population.

A variety of diverse methodological approaches have been developed and employed to quantify pelvic sexual dimorphism. Amongst the most readily applied are those based on the morphoscopic assessment of features known to be sexually dimorphic, such as the os pubis region following the method of Phenice [11], or the shape of the greater sciatic notch [12]. Other established methods employ the measurement and statistical analysis of distances and angles (morphometric—e.g. [13–15]) or 3D configurations of landmark coordinates (geometric morphometric—e.g. [16–21]). In a forensic context, the method(s) selected must by necessity be expedient and easy to apply, reliable (minimal subjectivism) but still yielding an acceptable accuracy rate with a small associated sex bias and a probabilistic estimate of the confidence in the prediction. Morphoscopic methods tend to be more subjective and less amenable to the quantification of accuracy rates and predictive confidence, albeit there is a burgeoning research interest in statistically facilitating the latter (e.g. [22, 23]). Less subjective morphometric approaches are, therefore, traditionally favoured when quantifiable accuracy and statistical confidence in the final estimation is required.

The present study joins an ongoing long-term research programme attempting to fortify forensic capabilities in contemporary Australia through the development and implementation of statistically sound methods for human identification based on novel analyses of 3D digital images. The latter has thus far involved both method validation studies [7, 8] and the formulation of anthropological standards [e.g. 24, 25]. This current research examines pelvic sexual dimorphism of contemporary adult Western Australians with the specific aim to quantify the reliability and accuracy of using measurements to estimate sex and to formulate a series of morphometric standards suitable for application in both complete and fragmentary pelves.

Materials and methods

Materials

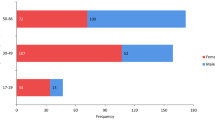

The pelvic measurements analysed in the present study were acquired from 3D volume-rendered multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT) scans of 400 individuals (200 males, 200 females) who presented to various Western Australian (Perth region) hospitals for pelvic clinical evaluation of symptoms most frequently relating to trauma, tumours and/or cancer and vascular disease. The MDCT scans are of patients admitted from 2005 to 2012, with 91 % of the study sample presenting for evaluation in 2011 to 2012 alone. The mean male age is 44.9 years (SD, 12.9) with a range of 18–64 and the mean female age is 45.3 years (SD, 11.5) with a range of 18–64 years. In Australia, research involving accessing patient data of living individuals must be in accordance with the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007–updated 2009) [26]. This requires all scans to be de-identified prior to receipt by the chief investigator (DF), with only sex and age data retained.

Patient ethnicity is not recorded at any time during clinical evaluation as such data is deemed not medically relevant. The ethnic composition of the sample overall is taken as being representative of the Western Australian population as a whole, which according to the latest census data is predominantly Caucasian in origin [27]. Scans presenting obvious congenital or acquired pelvic pathology (e.g. serious fractures) were excluded if normal morphology and/or our ability to acquire reliable measurements were compromised. Research ethics approval was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Western Australia (RA/4/1/4362).

Methods

Computed tomography data and pelvic measurements

Pelvic patient CT imaging was performed using MDCT on a Phillips Brilliance 64 scanner (Philips Healthcare, North Ryde, Australia) with an average beam width of 1.02 mm (range, 0.625–2.50 mm) and images reconstructed to the same slice thickness. Following 3D volume rendering, the 3D coordinates of 24 anatomical landmarks were acquired (by AF) using OsiriX® (version 3.9–64 bit); a total of 12 linear inter-landmark measurements and two angles are then calculated using MorphDb (an in-house developed database application). Landmarks are accordingly defined and illustrated in Table 1 and Fig. 1, respectively, with measurement definitions provided in Table 2.

Landmarks used in the present study (see Table 1 for landmark key)

Statistical analyses

Measurement precision was evaluated prior to primary data collection using four randomly selected pelves measured (by AF) on four occasions with a minimum of 1 day between repeat measurements. Intra-observer error was quantified using the relative technical error of measurement (rTEM) and coefficient of reliability (R)—see Ward et al. [28] and Weinberg et al. [29] for specific method. Quantification of bilateral measurement variation was performed in PERMANOVA using a hierarchical ANOVA to assess whether individual variation (i.e. the average of the two sides of each individual), even when the effect of sex is held constant, is significantly larger than residual variation (i.e. the differences between sides of each individual).

Normal descriptive statistics were calculated (i.e. mean, standard deviation, range), following which sexual dimorphism in the pelvis is assessed and quantified using one-way ANOVA. The sex prediction accuracy of the pelvic linear measurements and angles was explored through a series of cross-validated discriminant analysis employing direct (single and multiple variables) and stepwise approaches. The statistical robustness of the cross-validated discriminant analyses was further evaluated through the calculation of average and percentile (95 %) posterior probabilities for correctly classified individuals. Predictive accuracy of the morphometric variables was also compared using a receiver operator curve (ROC) and the corresponding area under curve (AUC); the 95 % confidence interval (CI) for AUC is also estimated [30]. For the most dimorphic traits, univariate measurement demarking points are calculated corresponding to the midpoint between mean female and male values, together with observed measurement values with posterior probabilities closest to 0.8, 0.9 and 0.95. Those readers seeking further detailed explanation of the latter statistical approaches can consult Franklin et al. [7, 8, 24] for specific methods.

Results

Precision of measurement and bilateral variation

The rTEM and R values calculated from the repeat measurements of four pelves are presented in Table 3. The rTEM values range between 0.41 % (transverse pelvic inlet) and 2.80 % (angle of the greater sciatic notch). With the exception of pubic and iliac lengths, all measurements have an R value ≥0.92. In all tests, averaged individual variation (with sex differences controlled for) is highly significantly larger (P < 0.001) than residual asymmetric variation (Table 4) and remains significant even after an over-conservative Bonferroni correction for eight tests (significance level alpha = 0.006). On the basis of these analyses, the measurement data for the left and right sides are accordingly averaged. It is important to note that all analyses involving combined linear measurements and angles are also evaluated using standardized variables (z scores) with results equivalent to those based on raw (non-standardized) data. Only the latter, which are more readily interpretable, are presented (Table 4).

Univariate comparisons

The mean, standard deviation and range of the 14 pelvic and sacral measurements are presented in Table 5. For the measurements taken in the complete pelvis (transverse pelvic inlet and outlet), it is apparent that the mean female values are significantly larger than those of the male individuals. Similarly, both pelvic angle measurements (subpubic angle and angle of the greater sciatic notch) are significantly larger in females. The mean values of the remaining measurements (with the exception of pubic length and sacral breadth) are statistically significantly larger in male individuals (Table 5). Sex differences explain up to 65.0 % of sample variance, and based on F-statistic values, the measurements expressing the greatest dimorphism are subpubic angle and transverse pelvic outlet (Table 5).

Cross-validated discriminant analyses

-

a.

Direct single variable

A series of single-variable DFAs are performed to evaluate the sex classification accuracy of the most sexually dimorphic individual measurements. Thus, only those measurements with an expected cross-validated accuracy of correct assignment by sex of ≥80 % and an associated sex bias of ≤5 % are presented. A total of five measurements met the required inclusion criteria (functions 1–5—Table 6), which thereafter are used to formulate demarking points (see “Demarking points” below). Subpubic angle has the highest sex classification rate (accuracy, 93.2 %; sex bias, −2.5 %); the accuracy of the remaining measurements range between 92.5 % (transverse pelvic outlet) and 81.2 % (iliac length) (Table 6).

-

b.

Direct and stepwise multiple variable

A series of direct multiple measurement (i.e. non-stepwise) discriminant standards, designed specifically for application in pelves of varying preservation, were formulated (functions 6–9). Expected classification accuracies range between 96.5 and 84.5 %, with associated sex biases of 0 to −3.0 % (Table 6). In the stepwise analysis, a total of 10 variables are selected, which correctly referred 100 % of individuals to their respective sex (Table 6). Discriminant equations, group centroids and sectioning point values for functions 6–10 are presented in Table 7.

-

c.

Classification accuracy and sex bias

The accuracy of the discriminant functions was further evaluated by plotting the average percentage of correctly classified individuals (Fig. 2a—solid black line). The sex bias is represented in the profile plot as a loss of accuracy by subtracting it from the classification accuracy (dashed grey line). Variables are rank ordered from highest to lowest accuracy for sex estimation. The highest accuracy achieved was 100 % for the stepwise analysis (function no. 10—10 variables selected), and the next most accurate predictors with an expected accuracy of 96.5 % (sex bias, −2.0 %) were the combined pelvic angles (subpubic angle and angle of the greater sciatic notch—function no. 8), followed by the innominate bone and subpubic angle (both with accuracies >90 % even when ‘corrected’ for the sex bias).

Performance of predictors in cross-validated discriminant analyses: a average percentage of correctly classified individuals before (black solid line) and after (grey dashed lines) subtracting the absolute value of the sex bias, b Posterior probability (PP) range for correctly classified individuals—average (black solid line) and percentiles including 95 % of observed PP (dashed grey lines) and c AUC (black solid line) and estimated CI. The grey shaded background is to emphasize the ranges with the highest observed accuracy (>90 %), confidence (>0.9) and AUC (>0.98)

Posterior probabilities

The predictors that showed the highest classification accuracy also had the highest mean posterior probabilities (e.g. functions 10, 8 and 9—all have average values above 0.95), and the mean posterior probabilities for the remaining functions are all larger than 0.85 (Table 6; Fig. 2b). The 95 % range of variation in posterior probabilities is relatively wide for all functions, although the lower boundary for the stepwise predictors is considerably higher at 0.981 (Table 6; Fig. 2b).

ROC/AUC and random chance baseline

The results of the AUC analysis are consistent with the classification accuracy and posterior probability data outlined above. The most accurate predictors and their relative order are identical with the stepwise predictors having the highest AUC value, followed by functions 8 and 9, respectively (Table 6; Fig. 2c). The overall difference between the highest and lowest AUC values is small (1.000–0.914), and when the predictors with the closest AUC values are compared, it is evident that, with the exception of the stepwise function, there is a degree of overlap in the estimated confidence intervals (Table 6; Fig. 2c). In all discriminant analyses, the average cross-validated classification accuracy is larger than both the empirical average random chance baseline (i.e. the probability of correctly classifying an individual by mere chance) and its 95th upper percentile, 50.0 and 55.0 %, respectively [see 31, 32].

Demarking points

Demarking points (midpoints and points with posterior probabilities ≥0.8) are presented in Table 8 for the best performing single measurements and visually summarized in Fig. 3 using a spider web plot, as in Franklin et al. [24]. Demarking points represent the respective threshold values for each measurement above or below male or female classification. If posterior probability values ≥0.80 are used as classification thresholds (instead of the ‘standard’ 0.50 value), average cross-validated predictive accuracy for individuals falling within those ranges is (depending on the measurement used) between 61.8 % (≥0.95) and 81.0 % (≥0.80) for the most accurate predictors (transverse pelvic outlet, subpubic angle) and between 27.8 % (≥0.95) and 61.8 % (≥0.80) for the least accurate variables (ischial length, acetabular width, angle of the greater sciatic notch).

Discussion

Diagnostic radiology is deeply entrenched in the forensic sciences, with recent significant advances including the Virtopsy Project [33], which clearly advocated the forensic potential of advanced imaging technologies. In modern practice, whole body postmortem imaging prior to autopsy is now largely recognized as a standard practice in most forensic institutes [34]. The rapid growth of forensic radiological and imaging techniques have, however, not only found widespread application in general forensic medicine, but also in other related disciplines, such as forensic anthropology. In considering applications in the latter discipline, MDCT scanning (both clinical and forensic) affords the opportunity to not only assess pathology and/or trauma in the human skeleton but to also acquire contemporary population-specific data that can be used to formulate standards for the estimation of routinely assessed biological attributes in the skeleton, including age [35–37], sex [8, 10, 24, 38, 39], and stature [39, 40].

The accurate estimation of sex in decomposed or skeletal remains is clearly an important consideration towards facilitating the identity of an unknown individual, especially since other elements of the biological profile are generally estimated using sex-specific standards (e.g. age and stature). The likelihood of an incorrect estimation is further compounded when non-population-specific standards are applied. With respect to the latter, the importance of developing contemporary standards utilizing biological data from medical imaging modalities (e.g. MDCT) cannot be understated. The results of this study clearly and expectedly establish that the pelvis is highly sexually dimorphic in a contemporary Western Australian population and that it is possible to estimate sex (whether intact or fragmented os coxae) with a high level of expected accuracy.

In considering the level of intra-observer measurement error, it was evident that 7/14 measurements had R values of ≥0.95 and 12/14 measurements were ≥0.90 (Table 3). There is little guidance in the published literature as what constitutes an ‘acceptable’ level of measurement error; however, in an analysis of linear data acquired in MDCT cranial scans, we previously asserted that any measurements with an R value below 0.90 should be treated cautiously, especially if the associated rTEM is above 5 % [7]. In the present study, there were only two measurements below that threshold (IL and PL), albeit both had low rTEM values (1.75 and 0.97 %), respectively (Table 3). It is known that measurements made in actual bone specimens tend to be more precise than their MDCT counterparts, although differences due to data acquisition techniques (including operator differences) may be negligible in relation to the population variance (e.g. [7]). Furthermore, by virtue of the specific anatomy of the adult pelvis, most landmarks are either defined by maxima of curvature (type II) or are extremal points (type III) [41]. Taken in combination, the latter imply that the precision of pelvic measurements will likely be lower than that expected of other regions, such as the skull, comprising a larger proportion of type I landmarks that are defined by discrete juxtapositions of tissues [7, 41]. Overall, this study demonstrates acceptably high precision in the acquisition of pelvic measurements from three-dimensionally reconstructed multi-slice computer tomography (MSCT) scans with a range of R and rTEM values (x̄, 0.94/1.32; min., 0.78/0.41; max., 1.0/2.80) very similar to that of a previous study on cranial data (x̄, 0.94/1.00; min., 0.75/0.41; max, 1.00/2.54 [7]).

The present study confirms that, of the bones thus far studied, the pelvis is the single most accurate element for the estimation of skeletal sex in a contemporary Western Australian population, as the highest classification accuracy achieved using cranial [24] and sternal [25] variables was 90.0 and 84.5 %, respectively. The high level of dimorphism in the pelvis is not unexpected given the morphology of this region is the result of a long-term adaptation to facilitate bipedal locomotion and parturition through the maternal birth canal [42]. One of the most dimorphic measurements (transverse pelvic outlet—Table 5) is part of the true pelvis, through which an infant must pass in the birthing process [43, 44]. The subpubic angle is also highly dimorphic (Table 5), with the wide angle observed in female individuals known to be (in part) related to the pronounced lateral growth of the ischia—another example of a morphological configuration inferentially related to obstetrics [45]. The mean subpubic angle values for the Western Australian population (♂, 69.0° and ♀, 89.4°) are comparable to previously published values in other populations (e.g. White South African: ♂, 70.7° and ♀, 93.9° [46]; White American: ♂, 63.7° and ♀, 88.4° [47]), which is consistent with both expectations in samples whose ancestry is mainly Caucasian, and the observation that the bias in MDCT data is small and has a negligible effect on accuracy.

The remaining measurements, with the exception of pubic length and the anterior height of the sacrum, demonstrate significant sexual dimorphism (Table 5). Nonsignificant sexual dimorphism in the measurement of pubic length appears to be common to other populations, including Black and White South Africans [2] and modern Italians [15]. In comparison to one recent study [1], mean anterior height of the sacrum for Western Australian males is similar to values reported for a modern Greek sample (e.g. 108.1 and 108.8 mm, respectively); however, the females of the former population presented comparatively larger mean values (106.2 and 101.7 mm, respectively) and are thus more similar in size to males from their population (hence, the lack of dimorphism). Irrespective, however, in this study, discriminant analysis of the sacral variables yielded poor sex classification accuracy (highest was 68.8 %), which is why no functions are presented for this bone. Zech et al. [48] report sex classification accuracy rates consistently below 80 % in their analysis of sacral CT scans, which similarly confirms comparatively lower levels of dimorphism in this bone.

In critically evaluating the accuracy of the various discriminant analyses performed, it is clearly evident that the highest expected accuracy and greatest confidence are achieved when the complete pelvis is available for analysis (e.g. functions 1 and 10—Table 6 and Fig. 2a). Regardless of robust statistical quantification in a large sample with validated results, however, it is pertinent to recommend due caution in expecting a faultless classification to hold true outside of the original study sample. With the addition of a larger study sample and by increased variability, it is possible that classification rates may be reduced. Justification of the latter supposition is beyond the scope of this research but it does offer an appropriate avenue for further investigation. In fact, to what extent our results are generalizable within or even outside Australia (e.g. other populations predominantly Caucasian in composition) is an appropriate avenue for further investigation by the wider anthropological community and offers an interesting possibility to explore the robustness (or weakness) of findings from one geographic region when applied elsewhere.

It is well supported in the literature that pelvic measurements can be used to estimate sex with expected classification rates above 90 % [e.g. 13–15, 49]. Previous similar studies in other populations demonstrate that using innominate measurements only (e.g. no pelvic angles or measurements of the true pelvis) it is possible to achieve classification accuracies of 93.5 % (modern Greek population [1]) to 94–95.5 % (South African populations [2]); both the combination of measurements used in those analyses and the level of accuracy achieved are comparable to function no. 9 of the present study (94.0 %—see Table 6 and Fig. 2a).

The various single-variable demarking points presented here contribute to provide simple measurements for a first numerical evaluation of sex and help to increase the applicability of our standards to damaged and/or fragmentary remains. These may be encountered where the mechanism of death involves explosive trauma, high velocity impacts, dismemberment or there has been deleterious postmortem influences, such as animal scavenging. Further, the spider web plot shown in Fig. 3 represents a relatively novel and intuitive visual tool for a rapid preliminary estimation of sex that offers statistical confidence in the degree of error and uncertainty in the final estimation.

Conclusion

This project has further contributed to the growing repository of contemporary morphometric anthropological standards for the Western Australian milieu, confirmed that a multivariate approach to numerical classification is most effective and also showed that even a single measurement, such as the subpubic angle, can predict sex in adults with more than 93 % cross-validated accuracy and an average posterior probability (i.e. predictive confidence) larger than 90 %. Although not yet tested on individuals outside of Western Australia, it is not unreasonable to theorize that these standards would have forensic utility in other Australian judiciaries. The statistically quantified and robust standards presented here are likely to be more representative of the Australian population as a whole compared to existing morphometric standards available in the published literature that are based on the analysis of geographically and/or temporally removed populations. Empirical testing of the latter assertions offers an interesting potential avenue of future research.

References

Steyn M, İşcan MY (2008) Metric sex determination from the pelvis in modern Greeks. Forensic Sci Int 179:86.e1–e6

Patriquin ML, Steyn M, Loth SR (2005) Metric analysis of sex differences in South African black and white pelves. Forensic Sci Int 147:119–127

Franklin D, Flavel A, Kuliukas A, Hart R, Marks MK (2012) The development of forensic anthropological standards in Western Australia. In: Proceedings of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences LXIV, pp. 361–362

Ross AH, Ubelaker DH, Kimmerle EH (2011) Implications of dimorphism, population variation, and secular change in estimating population affinity in the Iberian Peninsula. Forensic Sci Int 206:214-e1–214-e5

Franklin D, Freedman L, Milne N (2005) Sexual dimorphism and discriminant function sexing in indigenous South African crania. HOMO J Comput Hum Biol 55:213–228

Franklin D, Cardini A, Oxnard CE (2010) A geometric morphometric approach to the quantification of population variation in sub-Saharan African crania. Am J Hum Biol 22:23–35

Franklin D, Cardini A, Flavel A, Kuliukas A, Marks MK, Hart R, Oxnard C, O’Higgins P (2012) Concordance of traditional osteometric and volume-rendered MSCT interlandmark cranial measurements. Int J Leg Med 127:1–16

Franklin D, Cardini A, Flavel A, Kuliukas A (2012) Linear measurements and geometric morphometric data for quantifying cranial sexual dimorphism: preliminary investigations in a Western Australian population. Int J Leg Med 126:549–558

Verhoff MA, Marcel A, Ramsthaler F, Krähahn J, Deml U, Gille RJ, Grabherr S, Thali MJ, Kreutz K (2008) Digital forensic osteology—possibilities in cooperation with the Virtopsy® project. Forensic Sci Int 174:152–156

Ramsthaler F, Kettner M, Gehl A, Verhoff MA (2010) Digital forensic osteology: morphological sexing of skeletal remains using volume-rendered cranial CT scans. Forensic Sci Int 195:148–152

Phenice TW (1969) A newly developed visual method of sexing the os pubis. Am J Phys Anthropol 30:297–301

Buikstra JE, Ubelaker DH (1994) Standards for data collection from human skeletal remains, Arkansas Archaeological Survey Research Series No. 44, Arkansas

Schulter-Ellis FP, Hayek LC, Schmidt DJ (1985) Determination of sex with a discriminant analysis of new pelvic bone measurements: part II. J Forensic Sci 30:178–185

Gómez-Valdés JA, Ramírez GT, Molgado SB, Sain-Leu PH, Caballero JLC, Sánchez-Mejorada G (2011) Discriminant function analysis for sex assessment in pelvic girdle bones: sample from the contemporary Mexican population. J Forensic Sci 56:297–301

Vacca E, Di Vella G (2012) Metric characterization of the human coxal bone on a recent Italian sample and multivariate discriminant analysis to determine sex. Forensic Sci Int 222:401.e1–401.e9

Steyn M, Pretorius E, Hutten L (2004) Geometric morphometric analysis of the greater sciatic notch in South Africans. HOMO J Comput Hum Biol 54:197–206

Gonzalez PN, Bernal V, Perez SI (2009) Geometric morphometric approach to sex estimation of human pelvis. Forensic Sci Int 189:68–74

Bytheway JA, Ross AH (2010) A geometric morphometric approach to sex determination of the human adult os coxa. J Forensic Sci 55:859–864

Velemínská J, Krajíček V, Dupej J, Goméz-Valdés JA, Velemínský P, Šefčáková A, Pelikán J, Sánchez-Mejorada G, Brůžek J (2013) Technical note: geometric morphometrics and sexual dimorphism of the greater sciatic notch in adults from two skeletal collections: the accuracy and reliability of sex classification. Am J Phys Anthropol 152:558–565

Bilfeld MF, Dedouit F, Rousseau H, Sans N, Braga J, Rouge D, Telmon N (2012) Human coxal bone sexual dimorphism and multislice computed tomography: geometric morphometric analysis of 65 adults. J Forensic Sci 57:578–588

Franklin D, Flavel A, Cardini A, Marks MK (2013) Pelvic sexual dimorphism in a Western Australian population: integration of geometric and traditional morphometric approaches. In: Proceedings of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences LXV, pp. 419–420

Walker PL (2008) Sexing skulls using discriminant function analysis of visually assessed traits. Am J Phys Anthropol 136:39–50

Hefner JT (2009) Cranial nonmetric variation and estimating ancestry. J Forensic Sci 54:985–995

Franklin D, Cardini A, Flavel A, Kuliukas A (2013) Estimation of sex from cranial measurements in a Western Australian population. Forensic Sci Int 229:158.e1–158.e8

Franklin D, Flavel A, Kuliukas A, Cardini A, Marks MK, Oxnard CE, O’Higgins P (2012) Estimation of sex from sternal measurements in a Western Australian population. Forensic Sci Int 217:230.e1–230.e5

National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (2013) National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research—updated 2013. http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines/publications/e72

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2012) Ancestry. http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/censushome.nsf/home/factsheetsa?opendocument&navpos=450

Ward RE, Jamison PL (1991) Measurement precision and reliability in craniofacial anthropometry: implications and suggestions for clinical applications. J Craniofac Genet Dev Biol 11:156–164

Weinberg SM, Scott NM, Neiswanger K, Marazita ML (2005) Intraobserver error associated with measurements of the hand. Am J Hum Biol 17:368–371

Sanfilippo PG, Cardini A, Hewitt AW, Crowston JG, Mackey DA (2009) Optic disc morphology-rethinking shape. Prog Retin Eye Res 28:227–248

Kovarovic K, Aiello LC, Cardini A, Lockwood CA (2011) Discriminant function analyses in archaeology: are classification rates too good to be true? J Archaeol Sci 38:3006–3018

Evin A, Cucchi T, Cardini A, Vidarsdottir US, Larson G, Dobney K (2013) The long and winding road: identifying pig domestication through molar size and shape. J Archaeol Sci 40:735–743

Thali MJ, Yen K, Schweitzer W, Vock P, Boesch C, Ozdoba C, Schroth G, Sonnenschein M, Doernhoefer T, Scheurer E, Plattner T, Dirnhofer R (2003) Virtopsy, a new imaging horizon in forensic pathology: virtual autopsy by postmortem multislice computed tomography (MSCT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)—a feasibility study. J Forensic Sci 48:386–403

Manuela B, Winklhofer S, Hatch GM, Ampanozi G, Thali MJ, Ruder TD (2013) The rise of forensic and post-mortem radiology—analysis of the literature between the year 2000 and 2011. J Forensic Radiol Imaging 1:3–9

Franklin D, Flavel A (2014) Brief communication: timing of spheno-occipital closure in modern Western Australians. Am J Phys Anthropol 153:132–138

Bassed RB, Briggs C, Drummer OH (2011) Age estimation using CT imaging of the third molar tooth, the medial clavicular epiphysis, and the spheno-occipital synchondrosis: a multifactorial approach. Forensic Sci Int 212:273.e271–273.e275

Minier MD, Maret D, Vergnault M, Mokrane F, Rousseau H, Adalian P, Telmon N, Rouge D (2014) Fetal age estimation using MSCT scans of deciduous tooth germs. Int J Leg Med 128:177–182

Giurazza F, Schena E, Del Vescovo R, Cazzato RL, Mortato L. Saccomandi P, Paternostro F, Onofri L, Beomonte Zobel B (2013) Sex determination from scapular length measurements by CT scans images in a Caucasian population. In Conference proceedings: Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Conference, pp. 1632–1635

Decker SJ, Davy-Jow SL, Ford JM, Hilbelink DR (2011) Virtual determination of sex: metric and nonmetric traits of the adult pelvis from 3D computed tomography models. J Forensic Sci 56:1107–1114

Macaluso P, Lucena J (2014) Stature estimation from radiographic sternum length in a contemporary Spanish population. Int J Leg Med. doi:10.1007/s00414-014-0975-3

Bookstein FL (1997) Morphometric tools for landmark data: geometry and biology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Rosenberg K, Trevathan W (1996) Bipedalism and human birth: the obstetrical dilemma revisited. Evol Anthropol Issues News Rev 4:161–168

Oxorn H (1986) Oxorn-foote human labor & birth, 5th edn. Appleton, Norwalk

Rosenberg KR (1992) The evolution of modern human childbirth. Am J Phys Anthropol 35:89–124

Tague RG (1992) Sexual dimorphism in the human bony pelvis, with a consideration of the Neandertal pelvis from Kebara Cave, Israel. Am J Phys Anthropol 88:1–21

Small C, Brits DM, Hemingway J (2012) Quantification of the subpubic angle in South Africans. Forensic Sci Int 222:395.e1–395.e6

Tague RG (1989) Variation in pelvic size between males and females. Am J Phys Anthropol 80:59–71

Zech WD, Hatch G, Siegenthaler L, Thali MJ, Lösch S (2012) Sex determination from os sacrum by postmortem CT. Forensic Sci Int 221:39–43

Arsuaga JL, Carretero JM (1994) Multivariate analysis of the sexual dimorphism of the hip bone in a modern human population and in early hominids. Am J Phys Anthropol 93:241–257

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank A/Prof. Rob Hart, Frontier Medical Imaging International, Western Australia, for the assistance in obtaining the CT scans. We also offer our thanks to Dr Len Freedman and two anonymous referees for their helpful comments on this manuscript and to Dr. Allowen Evin for her fundamental help with the use of R. AC acknowledges the support of the Durham University Department of Anthropology and Durham International Fellowships for Research and Enterprise (DIFeREns) co-funded by Durham University and the European Union. We also acknowledge funding from a now completed ARC Discovery Grant (DP1092538) held by DF, AC and MKM.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Franklin, D., Cardini, A., Flavel, A. et al. Morphometric analysis of pelvic sexual dimorphism in a contemporary Western Australian population. Int J Legal Med 128, 861–872 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-014-0999-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-014-0999-8