Abstract

Purpose

Septoplasty is a common rhinological procedure intended to relieve symptoms of chronic nasal obstruction. However, there remains a question as to whether patients obtain symptom improvement and are satisfied with surgical outcomes in the months and years after septoplasty. This review aims to evaluate the long-term efficacy of functional septoplasty for nasal septal deviation.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature was conducted from November 2014 to March 2016 using the Cochrane, EMBASE, and PubMed databases. Prospective trials concerning functional septoplasty, which assessed subjective outcomes and included long-term follow-up data (≥ 9 month post-septoplasty) were included.

Results

2189 articles were screened with seven meeting the criteria for inclusion. Patient satisfaction was assessed in six studies, with rates of satisfaction provided in three of these, ranging from 69 to 100%. Two studies assessed the degree of patient satisfaction, with one study indicating that 88% of patients were moderately satisfied or better at 1 year post-op, and the other reporting that 50% of patients were satisfied. In assessing symptom relief, several methods were used, including validated questionnaires, with varying degrees of improvement in nasal obstruction reported.

Conclusions

Septoplasty appears to be a far from perfect treatment for nasal obstruction due to septal deviation. However, given the heterogeneity of data and lack of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), future RCTs and use of validated questionnaires would enable generation of superior levels of evidence. We suggest future prospective trials evaluating prognostic factors in septoplasty, to better inform patients and facilitate the development of guidelines for surgical intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chronic nasal obstruction (NO) is common with estimates of up to one-third of the general population [1, 2]. Of the proposed causes of nasal obstruction, nasal septal deviation (NSD) is also commonplace with studies, showing that half or more of the general population may have NSD, although not all people with septal deviation have associated obstructive symptoms [3,4,5]. Nasal obstruction attributed to nasal septal deviation has been demonstrated to be responsible for an array of symptoms that decrease patients’ quality of life [6]. Unsurprisingly, septoplasty is one of the most common rhinological procedures performed for the treatment of chronic nasal obstruction due to septal deviation, with a reported 260,000 operations completed in the United States in 2006 alone [2]. Outcomes of septoplasty can be divided into objective or subjective patient-reported outcome measurements (PROMs) [7]. One of the simplest subjective measurements is the proportion of patients satisfied. The Swedish Septoplasty Register, one of the nine sub-registers within the Swedish Quality Register of Otorhinolaryngology, is a large-scale database that reported a satisfaction rate of 76.5% among patients (n = 1868) who were surveyed 6 months after surgery [8]. Another commonly used PROM is the visual analogue scale (VAS). This is an easy tool that may be used to measure the level of satisfaction with surgery or the severity of symptoms; however, an issue with VAS is that of inter-rater variability [9]. To allow for more consistent measures of nasal symptoms, Steward et al. developed the Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) scale, which has become a widely used validated questionnaire for evaluating subjective nasal obstruction [6]. Other commonly used subjective measurements include the Fairley Nasal Symptom Questionnaire (FNQ), the SNOT-22, and the Glasgow Benefit Inventory (GBI) [7]. Of these scales, the NOSE, FNQ, and SNOT-22 are specific to rhinological symptom evaluation, while the GBI is more widely used to assess benefit from the full spectrum of otorhinolaryngological procedures [7]. Objective measures such as rhinomanometry and acoustic rhinometry have been studied as well, and a review of the literature indicates that septoplasty improves objective rhinometric outcomes [10].

However, there are conflicting data regarding correlation of objective and subjective outcomes of septoplasty, with some studies finding a correlation [11,12,13,14,15,16] and others that do not demonstrate any correlation [17,18,19,20,21]. With these varying results, some clinicians have put more emphasis on subjective outcomes as the primary outcome of clinical relevance [22]. There is a wide body of research into patient-related outcomes of septoplasty, yet the collective findings of long-term studies have not been analyzed.

The aim of this study is to review the existing evidence on PROMs from prospective trials with long-term follow-up duration, which was defined by the authors as 9 months or greater. Nine months were selected based on a long-term trial by Jessen et al. which showed no statistically significant difference in satisfaction rates between 9 month and 9 year post-operatively [23]. It was postulated that similar data from studies with a follow-up time beyond 9 months could potentially be generalizable to 9 years. We focused on evaluating patient satisfaction rates and the persistence of nasal obstruction symptoms. Our intention is to provide information that can help clinicians and patients evaluate whether septoplasty is a suitable treatment option for nasal obstruction due to septal deviation and thus minimize treatment failure.

Methods

The study design was informed by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist (http://www.prisma-statement.org). From Nov 2014 to Mar 2016, two authors searched the Pubmed, EMBASE, and Cochrane databases using MeSH search terms (Appendix A) using a database generated in November 2014. The target patient population was adults with nasal obstruction and nasal septal deviation treated with septoplasty as the only surgical intervention. Only prospective studies written in the English language that evaluated patient-related outcome measurements, with a minimum of 9 month follow-up were included. Data from an arm (or arms) of patients who met the above criteria within a trial were also included. For quality assurance, in March 2016, a repeat search was performed to look for additional papers meeting the inclusion criteria during the review timeframe, but this process was not included in the results, as no additional publications meeting the inclusion criteria were found by the searching author.

Assessment of quality

Quality assessment was performed independently by two reviewers using the criteria laid down in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions ‘Risk of Bias’ tool. An assessment was performed for six of the seven specific domains (types of bias) described in the handbook and a judgement of either “high” risk, “unclear” risk, or “low” risk was made. According to the handbook, the seventh domain (sequence generation) was not assessed, as allocation was not randomized in the studies included in this review.

Summary of data

A meta-analysis was not feasible for this review due to significant heterogeneity of data; therefore, a qualitative approach summarizing the results was completed.

Results

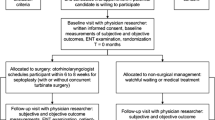

Two authors searched the PubMed and EMBASE databases, screening 2189 abstracts or full-length articles and assessing 200 full text articles for eligibility, with seven studies meeting the inclusion criteria and involving 461 patients for analysis. The reviewers were in complete agreement with Cohen’s kappa κ = 1 (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

We identified seven studies that satisfied the selection criteria for this review and each manuscript was fully examined by all authors. All studies were of prospective trials. Sample sizes ranged from 30 to 141 patients. Follow-up durations ranged from 9 months to 10 years. Patient ages ranged from 15 to 63 years [23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. The study characteristics are summarized in Table 1 with a detailed summary of subjective patient outcomes in Table 2.

Risk of bias

Figures 2 and 3, respectively, show the within-studies and across-studies risk of bias according to the domains of the Cochrane handbook ‘Risk of Bias’ tool. Notably, across all included studies, there was a high risk of selection bias in the form of lack of allocation concealment. Blinding proved to be problematic across all studies, with 100% of studies judged to have either high or unclear risk of bias in the form of participant, personnel, and outcome measure blinding. Additional information or clarification of results was sought from one group of investigators who were not available for reply [24]. Of the included studies, the study by Jessen et al. was found to be at high risk of bias in five of the six assessed domains, with the other domain (performance bias) judged to be of unclear risk [23]. The particular characteristics of the included studies, particularly the fact that patient-reported outcomes were sought via a variety of subjective scales, underlie the high risk of performance bias. The high risk of selection bias, performance bias, and detection bias were related to the fact that the studies were not controlled.

Patient satisfaction

In six of the studies, patient satisfaction was assessed by directly surveying patients to ascertain whether or not they felt satisfied with their surgery. The way in which satisfaction was reported varied among these studies: Three studies reported outcomes as either “satisfied” or “dissatisfied,” with satisfaction rates of 69% [23], 84% [24], and 100% [25]. Two studies assessed the degree of satisfaction with categorical responses [27, 29]. In the study by Illum, 50% of patients reported being satisfied, 22% were partly satisfied, with the remainder being unsatisfied at 5 year post-op [27]. Pirila et al. stratified the degree of satisfaction into “very high”, “high”, “moderate”, and “low”. The Pirila study reported that satisfaction was moderate or better in 88% of patients 1 year following septoplasty [29]. Two studies used numerical scales to assess levels of satisfaction after surgery [26, 27]. Haroon et al. obtained a mean satisfaction rate of 4.6, on a scale ranging from 0 (no sense of change) to 5 (highly satisfied) at an average follow-up time of 20.1 months after surgery [26]. Konstantinidis et al. report patient satisfaction in their discussion, but it appears that they may have equated improvement in nasal obstruction with patient satisfaction [28].

Quality of life

Konstantinidis et al. evaluated quality of life using the Glasgow benefit inventory to assess subjective outcomes 2–3 years after septoplasty. Patients were divided into “below criterion” or “above criterion” groups, based on the median postoperative FNQ score. Mean total GBI for the below and above criterion groups were 6.34 and 23.88, respectively. GBI results did not reflect a significant change in health status following septoplasty, even in the above criterion group [28].

Symptom relief after septoplasty

Sensation of nasal obstruction following septoplasty was assessed by several different methods. Haroon et al. used the NOSE scale 6, which evaluates obstruction along with nasal discharge and headache, giving a collective score based on all three symptoms. Septoplasty improved the mean sense of symptom score from 6 pre-operatively to 0.7 after surgery [26]. Konstantinidis et al. assessed symptoms using the FNQ. Improvement in mean FNQ score for nasal obstruction improved from 2.4 before septoplasty to 1.8 after surgery. Their FNQ analysis revealed that 45% of patients had improved nasal airflow, while 43% experienced no change, and 12% reported poorer breathing [28].

The other studies used did not employ validated questionnaires. De Sousa Fontes et al. used the “Overall evaluation of the severity of rhinosinusal symptoms” questionnaire, which originated from a guidance document by the Rhinosinusitis Initiative [25, 30]. Nasal obstruction is one of the ten symptoms assessed by this scoring system, and the number reported represents the sum of scores from the ten individual symptoms. The study found that septoplasty significantly decreased severity of nasal symptoms from 6.12 pre-operatively to 2.01 post-operatively [25]. Three studies assessed only the sensation of nasal obstruction [23, 27, 29]. Jessen et al. found that 26% of patients were free of nasal obstruction 9 years following septoplasty [23]. Pirila et al. reported that 40% of patients were totally free from obstruction and 35% had mild obstruction, compared to a preoperative assessment revealing 93% of patients reported their nasal obstruction to be moderately or more severe [29]. Illum found that 53% of patients had persistent nasal obstruction after surgery [27]. Bohlin did not directly state how many patients reported nasal obstruction after septoplasty, but did not that six patients underwent re-operation due to persistent nasal obstruction [24].

Correlation of subjective and objective outcomes

Pirila et al. reported a positive correlation between postoperative satisfaction and increased nasal valve area measured by acoustic rhinometry. The correlation was statistically significant with regard to minimal cross-sectional area at the nasal valve and the overall minimal cross-sectional area on the deviated side. In addition, there was an inverse correlation between satisfaction and decreased nasal flow on the pre-operatively wider side [29]. The other studies in this review did not statistically assess correlation between subjective and objective outcomes.

Follow-up duration

Follow-up duration ranged from 12 months to 10 years and 9 months. Included studies showed variable follow-up points. Jessen et al. followed up at 9 months and again at 9 years, and found that the number of patients satisfied did not significantly differ between the two assessments. However, when symptoms of nasal obstruction were assessed, 51% reported being symptom free at 9 months, whereas only 26% were symptom free at 9 years [23]. Studies in this review also included multiple follow-up times, but data from earlier assessments that did not meet the 9 month follow-up duration criterion were not included [26].

Discussion

Our review of long-term patient-reported outcome measures demonstrates that septoplasty may be beneficial for patients who suffer from nasal obstruction due to septal deviation, based on satisfaction rates and decreases in symptom severity from baseline. Despite these positive outcomes, many patients still experience nasal obstruction after surgery. In two of the studies in this review, more patients reported satisfaction with their surgery than reported being symptom free [23, 27]. In one of these studies, only 26% of patients reported being free of nasal obstruction after 9 years [23]. Furthermore, one study showed that septoplasty did not result in significant changes in health status as measured by GBI [28]. This demonstrates the need for improved patient selection and identification of prognostic factors to minimize failure rates.

A common finding in several studies was that patients with more severe degrees of nasal obstruction experienced increased benefit from septoplasty compared to those patients with milder obstruction [29, 31, 32]. While this is not surprising, there is much heterogeneity in the way nasal obstruction is assessed, making it difficult to reliably determine the level of symptom severity that would be indicative of significant benefit from septoplasty. In regard to patient derived measurements, the NOSE questionnaire is a promising validated system [6]. Lipan et al. developed a severity classification system based on NOSE scores that can be used for consistent assignment of degree of obstruction, but large-scale studies are still needed to validate its use [33]. Similar to the development of rhinometric recommendations for selecting septoplasty candidates by Holmstrom [34], perhaps, future studies could utilize a common standardized rating system to establish reliable levels of nasal obstruction, thus enabling identification of those patients who are most likely to benefit from septoplasty.

An issue with patient derived outcome measures is that they often do not correlate with objective measures [17,18,19,20,21]. In our review, only Pirila et al. statistically correlated subjective and objective measures by reporting a positive correlation between postoperative satisfaction and increased nasal valve area measured by acoustic rhinometry [29]. This is contrary to data presented by Andre through a methodical systematic review which found a lack of correlation between subjective sensations of obstruction and objective measurements by rhinomanometry or acoustic rhinometry [21]. With inconsistencies in the evidence, the value of objective measures in the routine assessment of patients for septoplasty remains in question, particularly given the added time and cost of these tests.

Currently, the standard for evaluating nasal obstruction due to septal deviation is history and physical exam, with the decision to operate based on clinical judgement [28]. It has been shown that clinical assessment by otolaryngologists has high sensitivity, specificity, and both positive- and negative predictive value, and was, therefore, concluded to be a sufficient tool for identifying patients with nasal obstruction and deviated septum who will need septoplasty [35]. In 2015, the American Academy of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery Foundation released a consensus document supporting the practice of clinical assessment in identifying suitable candidates for septoplasty, stating that history and physical exam are sufficient for determination of candidacy for septoplasty, acknowledging that additional tests may be helpful in certain cases [36]. As demonstrated by Konstantinidis, patients selected for septoplasty suffer a biopsychosocial morbidity of disease as evaluated on GBI, which is not corrected by this operation. Although its effect was not directly studied by Konstantinidis, it can reasonably be assumed to impact satisfaction [28]. Further research would need to be conducted to explore this assumption. Nevertheless, we have demonstrated in this review that septoplasty as a definitive long-term solution is questionable.

Thus, there is a clear need to identify factors that are of prognostic value for septoplasty. Several retrospective trials have revealed that the presence of anterior septal deviation and cases involving young patients hold a better prognosis [37, 38], while female gender, previous nasal surgery, allergic rhinitis, and low airway resistance on rhinomanometry are predictors of poor septoplasty outcomes [11, 39,40,41,42]. In this review, Bohlin et al. attributed high satisfaction rates partly to the exclusion of patients with obstruction due to mucosal swelling [24]. Similarly, Haroon et al. excluded patients with nasal symptoms due to allergy, and was able to demonstrate high patient satisfaction rates along with significant declines in obstructive symptoms [26]. In line with this data, Jessen et al. found that the proportion of patients with allergy had a lower satisfaction rate (43%) compared to the entire cohort (68%) [23]. Note, however, a study by Bothra et al., involved septoplasty on patients with allergic rhinitis, but reported that each of those patients felt satisfied with the surgery further illustrating the heterogeneity of outcomes [43]. While the aforementioned poor predictive factors may diminish the efficacy of septoplasty, surgical intervention may still be warranted in some of these cases, and further research is needed to better elucidate the predictors of both poor and favorable outcomes of functional septoplasty. Ideally, obtaining a better knowledge of outcome predictors will ensure the judicious selection of septoplasty patients, such that both subjective and objective measures of a successful outcome can be demonstrated. Ultimately, the goal of any procedure is to benefit the patient—therefore, it is of the utmost importance that septoplasty patients report high levels of satisfaction with their surgeries, whether or not there is an accompanying objective measure of procedural success. An RCT of surgical versus non-surgical management of NO due to NSD has been registered in The Netherlands which should produce exciting results for the future of nasal obstruction management [44].

While it is known that the feeling of nasal obstruction is more common in rhinological patients, another area needing more study is the potential for the association of other sino-nasal symptoms with the feeling of nasal obstruction [45]. The authors could not find any studies comparing correlations of various sino-nasal symptoms with the symptom of nasal obstruction, which raises the intriguing possibility that nasal obstruction may be not be the best evaluator of subjective outcome when performing septoplasty—at least in a subset of patients [45].

Another important consideration is that of patient-related psychological factors. Mental health conditions have been associated with nasal pathologies such as chronic rhinosinusitis; it would, therefore, be of value to study whether the presence of co-morbid mental health conditions in those with established nasal obstruction alters patient-reported outcomes [45]. The GBI is a validated general quality of life assessment, and the Sino-Nasal-Outcome-Test (SNOT-20 and SNOT-22) scales are validated sino-nasal quality of life assessments for rhinosinusitis that have also been used in septoplasty studies [46,47,48,49]. Within these are psychological domains evaluating fatigue, sadness, embarrassment, and frustration, among others [46,47,48]. A future study focusing on psychological factors and mental health issues with correlation to subjective outcomes of septoplasty may be warranted. Qualitative studies could also be embarked upon, to explore whether those burdened with psychological issues perceive airflow differently to those not having co-morbid psychological complaints.

Our study focused on assessing long-term subjective outcomes of septoplasty, since it can take several months for full recovery of the nasal structures after surgery. The study by Jessen et al. showed a decline in patients who were free from nasal obstruction at 9 years (26%) compared to 9 month post-op (51%) [23]. This finding is in agreement with data from a retrospective study by Sundh et al., which reported that 53% of patients were symptom free at 6 months post-operatively, but only 18% of patients remained symptom free at 34–70 months following septoplasty [50]. These results suggest that septoplasty may not be an effective solution to nasal obstruction long term. Many studies that were not included in this review also assessed patients at multiple time points, but did not extend their follow-up beyond our 9 month cutoff. It should be noted, however, that one study in this review found no difference in nasal symptom severity between earlier and later follow-up assessments [25]. Haroon et al. even found a positive temporal correlation between time and satisfaction with decreased nasal obstruction and increased satisfaction scores from the third to the 12th month review [26]. This suggests that early follow-up data may be generalizable to long-term outcomes.

Limitations of the review

Limitations of this review include the small number of included studies, exclusion of studies not published in English, heterogeneity of data, and percentage of loss to follow-up in the individual studies. Because of study variation across multiple categories, including patient population, surgical intervention, outcome measures, and follow-up duration, we were unable to perform a meta-analysis. In addition, because septoplasty is often combined with various associated procedures including turbinectomy, we attempted to limit variation by selecting studies that performed septoplasty only, with the caveat that this may not be generalizable to all otolaryngologists’ approach to the correction of nasal obstruction due to nasal septal deviation [27].

Conclusion

The manifestations of nasal airway obstruction are legion, and comprise a highly complex constellation of symptoms to assess, given the multitude of variables involved. Years of prospective trials in septoplasty suggest widely differing degrees of success in long-term patient-reported outcomes. Clinical assessment via history and physical exam has long been the gold standard in identifying patients for whom septoplasty is indicated, yet we have demonstrated in this review that it has not been sufficient to ensure consistently good outcomes for all patients. Further research is necessary to improve the quality of studies in the literature. It should also aim to improve the way in which candidacy for septoplasty is determined. In particular, a focus of future research should be to ascertain which preoperative characteristics are predictive of both subjectively and objectively positive septoplasty outcomes. In addition, resources should be devoted to establishing standardized methods for assessing symptom severity, to improve utility and enable accurate and easy comparison among populations and studies. Ultimately, identification of reliable prognostic factors will enable a more far-sighted and methodical approach to the selection of patients for functional septoplasty.

References

Vainio-Mattila J (1974) Correlations of nasal symptoms and signs in random sampling study. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 318:1–48

Bhattacharyya N (2010) Ambulatory sinus and nasal surgery in the United States: demographics and perioperative outcomes. Laryngoscope 120(3):635–638

Ahn JC et al (2016) Prevalence and risk factors of chronic rhinosinusitus, allergic rhinitis, and nasal septal deviation: results of the Korean national health and nutrition survey 2008–2012. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 142(2):162–167

Salihoglu M et al (2014) Examination versus subjective nasal obstruction in the evaluation of the nasal septal deviation. Rhinology 52(2):122–126

Stefanini R et al (2012) Systematic evaluation of the upper airway in the adult population of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 146(5):757–763

Stewart MG et al (2004) Development and validation of the Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) scale. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 130(2):157–163

Rhee JS, McMullin BT (2008) Outcome measures in facial plastic surgery: patient-reported and clinical efficacy measures. Arch Facial Plast Surg 10(3):194–207

Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, S.N.B.o.H.a.W. (2013) Quality and Efficiency in Swedish Health Care—Regional Comparisons 2012, S.N.B.o.H.a. Welfare, Editor. Ordförrådet AB, Stockholm

Andrews PJ et al (2015) The need for an objective measure in septorhinoplasty surgery: are we any closer to finding an answer? Clin Otolaryngol 40(6):698–703

Moore, M. and R. Eccles (2011) Objective evidence for the efficacy of surgical management of the deviated septum as a treatment for chronic nasal obstruction: a systematic review. Clin Otolaryngol 36(2):106–113

Sipila J, Suonpaa J (1997) A prospective study using rhinomanometry and patient clinical satisfaction to determine if objective measurements of nasal airway resistance can improve the quality of septoplasty. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 254(8):387–390

Tompos T et al (2010) Sensation of nasal patency compared to rhinomanometric results after septoplasty. Eur Arch Oto Rhino Laryngo 267(12):1887–1891

Kjaergaard T, Cvancarova M, Steinsvag SK (2009) Nasal congestion index: a measure for nasal obstruction. Laryngoscope 119(8):1628–1632

Larsen K, Oxhoj H (1988) Spirometric forced volume measurements in the assessment of nasal patency after septoplasty. A prospective clinical study. Rhinology 26(3):203–208

Kimbell JS et al (2012) Computed nasal resistance compared with patient-reported symptoms in surgically treated nasal airway passages: a preliminary report. Am J Rhinol Allergy 26(3):e94–e98

Murrell GL (2014) Correlation between subjective and objective results in nasal surgery. Aesthet Surg J 34(2):249–257

Constantinides MS, Adamson PA, Cole P (1996) The long-term effects of open cosmetic septorhinoplasty on nasal air flow. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 122(1):41–45

Kahveci OK et al (2012) The efficiency of Nose Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) scale on patients with nasal septal deviation. Auris Nasus Larynx 39(3):275–279

Daudia A et al (2006) A prospective objective study of the cosmetic sequelae of nasal septal surgery. Acta Otolaryngol 126(11):1201–1205

Hsu HC et al (2017) Evaluation of nasal patency by visual analogue scale/nasal obstruction symptom evaluation questionnaires and anterior active rhinomanometry after septoplasty: a retrospective one-year follow-up cohort study. Clin Otolaryngol 42(1):53–59

Andre RF et al (2009) Correlation between subjective and objective evaluation of the nasal airway. A systematic review of the highest level of evidence. Clin Otolaryngol 34(6):518–525

Arunachalam PS et al (2001) Nasal septal surgery: evaluation of symptomatic and general health outcomes. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 26(5):367–370

Jessen M, Ivarsson A, Malm L (1989) Nasal airway resistance and symptoms after functional septoplasty: comparison of findings at 9 months and 9 years. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 14(3):231–234

Bohlin L, Dahlqvist A (1994) Nasal airway resistance and complications following functional septoplasty: a ten-year follow-up study. Rhinology 32(4):195–197

De Sousa Fontes A, Sandrea Jimenez M, Chacaltana Ayerve RR (2013) Endoscopic septoplasty in primary cases using electromechanical instruments: surgical technique, efficacy and results. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp 64(5):317–322

Haroon Y, Saleh HA, Abou-Issa AH (2013) Nasal soft tissue obstruction improvement after septoplasty without turbinectomy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 270(10):2649–2655

Illum P (1997) Septoplasty and compensatory inferior turbinate hypertrophy: long-term results after randomized turbinoplasty. Eur Arch Oto Rhino Laryngol 254(Suppl 1):S89–S92

Konstantinidis I et al (2005) Long term results following nasal septal surgery. Focus on patients’ satisfaction. Auris Nasus Larynx 32(4):369–374

Pirila T, Tikanto J (2001) Unilateral and bilateral effects of nasal septum surgery demonstrated with acoustic rhinometry, rhinomanometry, and subjective assessment. Am J Rhinol 15(2):127–133

Meltzer EO et al (2006) Rhinosinusitis: developing guidance for clinical trials. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 135(5 Suppl):S31–S80

Anderson K et al (2016) The impact of septoplasty on health-related quality of life in paediatric patients. Clin Otolaryngol 41(2):144–148

Hong SD et al (2015) Predictive factors of subjective outcomes after septoplasty with and without turbinoplasty: can individual perceptual differences of the air passage be a main factor? Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 5(7):616–621

Lipan MJ, Most SP (2013) Development of a severity classification system for subjective nasal obstruction. JAMA Facial Plast Surg 15(5):358–361

Holmstrom M (2010) The use of objective measures in selecting patients for septal surgery. Rhinology 48(4):387–393

Sedaghat AR et al (2013) Clinical assessment is an accurate predictor of which patients will need septoplasty. Laryngoscope 123(1):48–52

Han JK et al (2015) Clinical consensus statement: septoplasty with or without inferior turbinate reduction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 153(5):708–720

Dinis PB, Haider H (2002) Septoplasty: long-term evaluation of results. Am J Otolaryngol 23(2):85–90

Gandomi B, Bayat A, Kazemei T (2010) Outcomes of septoplasty in young adults: the Nasal Obstruction Septoplasty Effectiveness study. Am J Otolaryngol 31(3):189–192

Siegel NS et al (2000) Outcomes of septoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 122(2):228–232

Zeng R et al (2014) Univariate and multivariate analyses for postoperative bleeding after nasal endoscopic surgery. Acta Otolaryngol 134(5):520–524

Karatzanis AD et al (2009) Septoplasty outcome in patients with and without allergic rhinitis. Rhinology 47(4):444–449

Mondina M et al (2012) Assessment of nasal septoplasty using NOSE and RhinoQoL questionnaires. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 269(10):2189–2195

Bothra R, Mathur NN (2009) Comparative evaluation of conventional versus endoscopic septoplasty for limited septal deviation and spur. J Laryngol Otol 123(7):737–741

van Egmond MM et al (2015) Effectiveness of septoplasty versus non-surgical management for nasal obstruction due to a deviated nasal septum in adults: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 16:500

Prus-Ostaszewska M et al (2017) The correlation of the results of the survey SNOT-20 of objective studies of nasal obstruction and the geometry of the nasal cavities. Otolaryngol Pol 71(2):1–7

Hopkins C et al (2009) Psychometric validity of the 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test. Clin Otolaryngol 34(5):447–454

Piccirillo JF, Merritt Jr MG, Richards ML (2002) Psychometric and clinimetric validity of the 20-Item Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT-20). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 126(1):41–47

Robinson K, Gatehouse S, Browning GG (1996) Measuring patient benefit from otorhinolaryngological surgery and therapy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 105(6):415–422

Bugten V et al (2016) Quality of life and symptoms before and after nasal septoplasty compared with healthy individuals. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord 16:13.

Sundh C, Sunnergren O (2015) Long-term symptom relief after septoplasty. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 272(10):2871–2875

Acknowledgements

Mr. Lars Eriksson for his expertise in generating search criteria. Dr. Emma Badenoch-Jones for her guidance and support in the systematic review of journal articles.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors do not have any financial conflicts of interest. One author is a practicing Otolaryngologist who performs septoplasty as a non-financial conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tsang, C.L.N., Nguyen, T., Sivesind, T. et al. Long-term patient-related outcome measures of septoplasty: a systematic review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 275, 1039–1048 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-018-4874-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-018-4874-y