Abstract

The objective of the study was to determine the evidence of intratympanic steroids injections (ITSI) for efficacy in the management of the following inner ear diseases: Ménière’s disease, tinnitus, noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) and idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss (ISSNHL). The data sources were literature review from 1946 to December 2014, PubMed and Medline. A systematic review of the existing literature was performed. Databases were searched for all human prospective randomized clinical trials using ITSI in at least one treatment group. The authors identified 29 prospective randomized clinical trials investigating the benefits of an intratympanic delivery of steroids. Six articles on Ménière’s disease were identified, of which one favored ITSI over placebo in vertigo control. Of the five randomized clinical trials on tinnitus therapy, one study found better tinnitus control with ITSI. The only available trial on NIHL showed significant hearing recovery with combination therapy (ITSI and oral steroids therapy). Seventeen studies were identified on ISSNHL, of which 10 investigated ITSI as a first-line therapy and 7 as a salvage therapy. Studies analysis found benefits in hearing recovery in both settings. Due to heterogeneity in treatment protocols and follow-up, a meta-analysis was not performed. Given the low adverse effects rates of ITSI therapy and good patient tolerability, local delivery should be considered as an interesting adjunct to the therapy of the ISSNHL and NIHL. Only one article over six where ITSI therapy offers potential benefits to patients with Ménière’s disease in the control of tinnitus and vertigo was found. ITSI does not seem to be effective in the treatment of tinnitus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Intratympanic injections for inner ear disease were first described by Trowbridge in 1944 [1] and a variety of treatment protocols have since been suggested. The rationale of locally delivered steroids is to allow the drug to reach tissues of interest with a high dosage, yet avoiding the adverse effects of systemic administration. The semi-permeable properties of the round window membrane allow intratympanic steroids to access the perilymph by pinocytosis and diffusion [2]. This bypassing of the hemato-cochlear barrier results in up to 1.270-fold higher steroids concentrations into the perilymph [3] when compared to systemic administration.

Corticosteroid receptors have been identified in both cochlear and vestibular tissues, suggesting that gene expression can be altered to produce anti-inflammatory effects [4]. Dexamethasone intratympanic injections have been shown to increase cochlear blood flow by 29 % [5] and increase the expression of aquaporin-1 [6], a key regulator in perilymphatic fluid homeostasis. Therefore, the inner ear’s physiology can be modulated by steroids and this explains why neurotologic disorders that have an inflammatory origin may respond to this drug.

This article reviews published evidence on the use of locally delivered steroids for treatment of inner ear pathologies suspected to have an inflammatory or autoimmune physiopathology. The objective is to identify inner ear diseases for which patients can benefit from ITSI.

Method

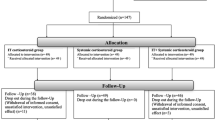

After approval from our institutional review board committee, PubMed and Medline Databases were searched for all human prospective randomized clinical trials with a treatment arm receiving ITSI. The following research terms were used: steroids, corticosteroids, prednisolone, methylprednisolone, dexamethasone glucocorticoids, intratympanic, transtympanic, inner ear disease, labyrinth diseases. Inner ear diseases of interest were identified through article titles and individually added to the search protocol. Authors reviewed all potential papers based on available abstracts and complete articles analysis. Articles’ references were also screened for potential additional studies. When multiple articles had been published by the same author for a growing series of patients, only the latest article, hence the one with the largest number of participants was included. Articles in languages other than English and French were also excluded. Database search included studies published between 1946 and December 2014.

Results

Databases search identified four inner ear diseases for which ITSI was used in a prospective randomized clinical trial: Ménière’s Disease, tinnitus, noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) and idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss (ISSNHL). After duplicates removal and screening, 29 articles remained for analysis.

For Ménière’s Disease, 6 articles were identified and listed in Table 1. When feasible, extraction of study data followed the recommendations of the Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery [7]. Of the selected articles, three [8–10] found no benefit of ITSI over placebo. One of these studies [10] compared a dexamethasone poloxamer gel to a placebo and found no statistical significance (p = 0.086) in the reduction of number of vertigo-days per month (−0.201 vs −0.124) and no statistical significance (p = 0.055) in the reduction of the tinnitus handicap inventory score (−15.0 vs −4.0).

One study [11] found that low-dose intratympanic gentamycin injections (ITGI) provided better vertigo control over ITSI and another found that vertigo was similarly controlled with ITGI, ITSI and endolymphatic sac decompression (ESD) [12].

In the remaining study, Garduno-Aaya et al. [2] found better vertigo control with ITSI over placebo (82 vs 57 %), a statistically significant improvement in subjective hearing (35 vs 10 %) and a statistically significant improvement in subjective tinnitus loudness and aural fullness (48 vs 20 %).

For tinnitus control, five prospective randomized trials were identified and listed in Table 2. Three studies [13–15] compared ITSI to placebo and found no benefit in tinnitus score improvement. One study [16] compared intratympanic dexamethasone, intratympanic prednisolone and oral carbamazepine and found no benefit in the ITSI groups. The study by Shim et al. [17] is the only study where tinnitus was improved in a statistically significant manner with ITSI (25.8 vs 9.8 % in control group).

In the treatment of NIHL, only one randomized clinical trial on humans was available [18] (Table 3). Of the 27 patients receiving combination therapy (systemic and ITSI), 51.9 % improved their pure tone average (PTA) by more than 15 dB and 66.7 % improved their speech discrimination score (SDS) by 15 % or more. Recovery rates for PTA and SDS were significantly better in the combination therapy group when compared to systemic therapy alone.

Ten studies investigated ITSI as first-line therapy for ISSNHL recovery (Table 4). Two studies [19, 20] found that ITSI therapy was equivalent to systemic therapy in hearing level (HL) improvement, and one [21] found that combination therapy was similar to systemic steroids. Of the two studies [22, 23] comparing systemic, ITSI and combination therapy, one found that combination therapy was superior to systemic treatment alone (87.5 vs 44.4 %). As for the four remaining studies, three [24–26] found that combination therapy was superior to systemic therapy and one [27] favored ITSI over placebo.

For salvage therapy in ISSNHL, 8 studies were identified (Table 5). All but one found that ITSI therapy was superior to control, placebo or systemic therapy.

Discussion

A meta-analysis of the identified literature was not performed due to the heterogeneous nature of the data. Studies used different treatment protocols, definitions of SSNHL and Ménière’s disease, definitions of outcome criteria, and timeframes for follow-up. Reported studies described the use of different steroids: dexamethasone or methylprednisolone. A single study [16] in our review compared methylprednisolone to dexamethasone injections and found no difference in tinnitus control between groups. In their pharmacokinetics studies in 1999, Parnes et al. [28] compared these two molecules. They found that methylprednisolone was superior to dexamethasone as peak concentrations were higher and remained higher for longer duration. Other authors have argued that higher concentrations of methylprednisolone were sampled in the endolymph due to decreased absorption by cochlear and vestibular tissues. To this day, no clinical data favors one over the other.

Given the natural evolution of Ménière’s disease, it has been suggested that study protocols always include a placebo group. Of the listed studies in Table 1, only 3 included a placebo group. The studies by Lambert et al. [10] and Garduno-Aaya et al. [2] were both of Level 1 evidence [29], but only the latter suggested benefits in vertigo and tinnitus control over placebo. The study by Silverstein et al. [8] found no difference between ITSI and placebo, but was criticized for being a crossover study. No benefits were found at 3 weeks, before the crossover, the only time point unbiased by the potential carry-over effect.

Paragache et al. [9] compared ITSI to medical therapy, comprising salt, caffeine, nicotine and alcohol restriction with cinnarizine and betahistidine hydrochloride. No difference was measured between the two groups in vertigo, tinnitus or hearing loss recovery (Table 1). However, the patients in the ITSI group were instilled the lowest dexamethasone concentration of all reported studies in this review: 20 times less than the usually used concentration of 4 mg/mL. With the expected dose–response relationship of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases to steroids, one can expect that the used steroid concentration was too low to produce any therapeutic effect.

The two remaining randomized studies interested in Ménière’s disease compared ITSI to ITGI. Together with our previously published local experience [30], ITGI seems to offers better vertigo control over ITSI. However, given the potential cochlear toxicity of gentamycin, ITGI should only be considered for patients with non-serviceable hearing.

In tinnitus therapy, one study [17] found benefits of ITSI over a control group. Patients were selected for having unilateral idiopathic tinnitus for less than 3 months. The authors hypothesized that in the early stage of disease; the cochlear lesion causing tinnitus can be reversed. Because minimal plastic change has occurred in the central auditory pathway, early administration of ITSI may enable cochlear lesion recovery and restore neural hyperactivities of the central auditory pathway. Unfortunately, there was no placebo group in this study so results were not compared to the natural evolution of the disease. Also, patients’ last follow-up was at 3 months, so long-term benefits were not assessed. Yet, this study suggests that patients might benefit from a reduced time between tinnitus onset and therapy.

Zhou et al. [18] found that combination therapy was superior to systemic steroids alone for patients exposed to noise trauma who had shown no spontaneous recovery within the first 72 h. Eighty-one percent of the recruited patients had been exposed to fireworks or military training noise. The therapeutic effects of steroids are thought to arise from their protective effects on injured cells [31, 32] by stabilization of cellular membranes, scavenging of oxygen free radicals and by inhibition of phospholipase A2. This first human study on ITSI therapy for NIHL shows promising results. However, sample size was small (53 patients) and patient selection was heterogeneous. Further studies are needed to confirm these benefits.

The use of ITSI for treatment of ISSNHL has been studied in two settings: as first-line and as salvage therapy. Given the unethical considerations of offering placebo as first-line therapy to patients suffering from ISSNHL, most studies compared combination to systemic therapy.

Four of these studies found that combination therapy was superior to systemic therapy alone and three found that combination therapy was equivalent to systemic treatment. Hence as first-line therapy of ISSNHL, adding ITSI to systemic therapy significantly improved patients’ outcome in more than half of the available studies. The used steroid concentrations in the positive studies ranged from methylprednisolone 12 mg/mL to dexamethasone 12 mg/mL (Table 4). Furthermore, Rauch et al. [19] designed a non-inferiority trial involving 205 patients and found that ITSI alone was not inferior to oral therapy. Hence, with recovery rates ranging from 55 % [22] to 96 % [27] the added benefits of ITSI need to be considered. The addition of ITSI to ISSNHL therapy may allow the use of lower systemic doses, thereby minimizing their adverse effects.

When considering salvage therapy in ISSNHL, ITSI groups had PTA improvement of 15 dB or more that ranged from 37.5 % [33] to 54.5 % [34]. The benefits on hearing levels were also significantly higher with ITSI in all but one study. Hence the available evidence supports the use of ITSI in salvage therapy.

In the six positive studies reported in Table 5, salvage therapy was administered, if no response was noted, 10–13 days after first-line systemic therapy. The used steroid concentration ranged from methylprednisolone 40 mg/mL to dexamethasone 5 mg/mL. Therefore, physicians should consider offering ITSI to patients suffering from ISSNHL after as little as 10 days into an unsuccessful first-line systemic therapy regiment.

Adverse events of ITSI therapy include ear pain at time of injection, caloric vertigo, dizziness, infection and persistent tympanic perforation. All of these side effects are either transient or easily curable. Pain and caloric vertigo can be, respectively, minimized with the use of fine needles and adequate steroid temperature at time of injection. Hence, when compared to systemic administration of steroids, intratympanic delivery is safe and can easily be managed by otolaryngologists.

Conclusion

Due to heterogeneity in treatment protocols and follow-up, a meta-analysis was not performed. Our review found only one article over six where ITSI therapy offers potential benefits to patients with Ménière’s disease in the control of tinnitus and vertigo. Patients affected with ISSNHL seem to benefit from ITSI in both first-line and salvage therapy. Only one human study was found on NIHL and its results showed a statistically significant improvement on hearing thresholds. Furthermore, our review showed that ITSI does not seem to be effective in the treatment of tinnitus.

Given the low adverse effects rates of ITSI therapy and good patient tolerability, local delivery should be considered as an interesting adjunct to the therapy of the idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss and noise induced hearing loss. However, despite the number of published studies on this delivery modality, it is yet difficult to recommend a specific treatment protocols for these inner ear conditions. A tailored approach based on patient’s tolerance and response seems most appropriate. The inner ear diseases presented in this study are all thought arise from an inflammatory or an autoimmune process. Therefore, expect a dose–response relationship with ITSI therapy and future local delivery devices offering increased and prolonged release might improve recovery rates.

References

Trowbridge BC (1944) Injection of the tympanum for chronic conductive deafness and associated tinnitus aurium: a preliminary report on the use of ethylmorphine hydrochloride. Arch Otolaryngol 39(6):523–526. doi:10.1001/archotol.1944.00680010542012

Garduno-Anaya MA, Couthino De Toledo H, Hinojosa-Gonzalez R, Pane-Pianese C, Rios-Castaneda LC (2005) Dexamethasone inner ear perfusion by intratympanic injection in unilateral Meniere’s disease: a two-year prospective, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 133(2):285–294. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2005.05.010

Bird PA, Begg EJ, Zhang M, Keast AT, Murray DP, Balkany TJ (2007) Intratympanic versus intravenous delivery of methylprednisolone to cochlear perilymph. Otol Neurotol 28(8):1124–1130. doi:10.1097/MAO.0b013e31815aee21

Rarey KE, Curtis LM (1996) Receptors for glucocorticoids in the human inner ear. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 115(1):38–41

Shirwany NA, Seidman MD, Tang W (1998) Effect of transtympanic injection of steroids on cochlear blood flow, auditory sensitivity, and histology in the guinea pig. Am J Otol 19(2):230–235

Fukushima M, Kitahara T, Fuse Y, Uno K, Doi K, Kubo T (2004) Changes in aquaporin expression in the inner ear of the rat after i.p. injection of steroids. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 553:13–18. doi:10.1080/03655230410017599

Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium guidelines for the diagnosis and evaluation of therapy in Meniere’s disease. American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Foundation, Inc (1995) Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 113(3):181–185

Silverstein H, Isaacson JE, Olds MJ, Rowan PT, Rosenberg S (1998) Dexamethasone inner ear perfusion for the treatment of Meniere’s disease: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, crossover trial. Am J Otol 19(2):196–201

Paragache G, Panda NK, Ragunathan M, Sridhara (2005) Intratympanic dexamethasone application in Meniere’s disease-Is it superior to conventional therapy? Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 57(1):21–23. doi:10.1007/bf02907620

Lambert P, Lambert S, Nguyen K, Maxwell D, Tucci L, Lustig M, Fletcher M, Bear C (2012) A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study to assess safety and clinical activity of OTO-104 Given as a single intratympanic injection in patients with unilateral Ménière’s Disease. Otol Neurotol 33(7):1257–1265

Casani AP, Piaggi P, Cerchiai N, Seccia V, Franceschini SS, Dallan I (2012) Intratympanic treatment of intractable unilateral Meniere disease: gentamicin or dexamethasone? A randomized controlled trial. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 146(3):430–437. doi:10.1177/0194599811429432

Sennaroglu L, Sennaroglu G, Gursel B, Dini FM (2001) Intratympanic dexamethasone, intratympanic gentamicin, and endolymphatic sac surgery for intractable vertigo in Meniere’s disease. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 125(5):537–543

Choi SJ, Lee JB, Lim HJ, In SM, Kim JY, Bae KH, Choung YH (2013) Intratympanic dexamethasone injection for refractory tinnitus: prospective placebo-controlled study. Laryngoscope 123(11):2817–2822. doi:10.1002/lary.24126

Araujo MF, Oliveira CA, Bahmad FM Jr (2005) Intratympanic dexamethasone injections as a treatment for severe, disabling tinnitus: does it work? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 131(2):113–117. doi:10.1001/archotol.131.2.113

Topak M, Topak A, Sahin Yilmaz T, Ozdoganoglu HB, Yilmaz M, Ozbay M (2009) Intratympanic methylprednisolone injections for subjective tinnitus. J Laryngol Otol 123(11):1221–1225

She W, Dai Y, Du X, Yu C, Chen F, Wang J, Qin X (2010) Hearing evaluation of intratympanic methylprednisolone perfusion for refractory sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 142(2):266–271. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2009.10.046

Shim HJ, Song SJ, Choi AY, Hyung Lee R, Yoon SW (2011) Comparison of various treatment modalities for acute tinnitus. Laryngoscope 121(12):2619–2625. doi:10.1002/lary.22350

Zhou Y, Zheng G, Zheng H, Zhou R, Zhu X, Zhang Q (2013) Primary observation of early transtympanic steroid injection in patients with delayed treatment of noise-induced hearing loss. Audiol Neurootol 18(2):89–94. doi:10.1159/000345208

Rauch SD, Halpin CF, Antonelli PJ, Babu S, Carey JP, Gantz BJ, Goebel JA, Hammerschlag PE, Harris JP, Isaacson B, Lee D, Linstrom CJ, Parnes LS, Shi H, Slattery WH, Telian SA, Vrabec JT, Reda DJ (2011) Oral vs intratympanic corticosteroid therapy for idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a randomized trial. JAMA 305(20):2071–2079. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.679

Hong SM, Park CH, Lee JH (2009) Hearing outcomes of daily intratympanic dexamethasone alone as a primary treatment modality for ISSHL. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 141(5):579–583. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2009.08.009

Koltsidopoulos P, Bibas A, Sismanis A, Tzonou A, Seggas I (2013) Intratympanic and systemic steroids for sudden hearing loss. Otol Neurotol 34(4):771–776. doi:10.1097/MAO.0b013e31828bb567

Lim HJ, Kim YT, Choi SJ, Lee JB, Park HY, Park K, Choung YH (2013) Efficacy of 3 different steroid treatments for sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a prospective, randomized trial. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 148(1):121–127. doi:10.1177/0194599812464475

Battaglia A, Burchette R, Cueva R (2008) Combination therapy (intratympanic dexamethasone + high-dose prednisone taper) for the treatment of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Otol Neurotol 29(4):453–460. doi:10.1097/MAO.0b013e318168da7a

Arastou S, Tajedini A, Borghei P (2013) Combined intratympanic and systemic steroid therapy for poor-prognosis sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Iran J otorhinolaryngol 25(70):23–28

Gundogan O, Pinar E, Imre A, Ozturkcan S, Cokmez O, Yigiter AC (2013) Therapeutic efficacy of the combination of intratympanic methylprednisolone and oral steroid for idiopathic sudden deafness. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 149(5):753–758. doi:10.1177/0194599813500754

Arslan N, Oguz H, Demirci M, Safak MA, Islam A, Kaytez SK, Samim E (2011) Combined intratympanic and systemic use of steroids for idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Otol Neurotol 32(3):393–397. doi:10.1097/MAO.0b013e318206fdfa

Filipo R, Attanasio G, Russo FY, Viccaro M, Mancini P, Covelli E (2013) Intratympanic steroid therapy in moderate sudden hearing loss: a randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Laryngoscope 123(3):774–778. doi:10.1002/lary.23678

Parnes LS, Sun AH, Freeman DJ (1999) Corticosteroid pharmacokinetics in the inner ear fluids: an animal study followed by clinical application. Laryngoscope 109(7 Pt 2):1–17

Phillips B BC, Sackett D et al (2009) Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine levels of evidence (last updated March 2009). http://www.cebm.net/?o=1025. Accessed April 2014

Gabra N, Saliba I (2013) The effect of intratympanic methylprednisolone and gentamicin injection on Meniere’s disease. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 148(4):642–647. doi:10.1177/0194599812472882

Hall ED (1992) The neuroprotective pharmacology of methylprednisolone. J Neurosurg 76(1):13–22. doi:10.3171/jns.1992.76.1.0013

Kawabata H, Takada K, Katori R (1995) Effect of methylprednisolone on metabolism and contractility in the stunned myocardium. Angiology 46(10):895–904

Li P, Zeng XL, Ye J, Yang QT, Zhang GH, Li Y (2011) Intratympanic methylprednisolone improves hearing function in refractory sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a control study. Audiol Neurootol 16(3):198–202. doi:10.1159/000320838

Plontke SK, Lowenheim H, Mertens J, Engel C, Meisner C, Weidner A, Zimmermann R, Preyer S, Koitschev A, Zenner HP (2009) Randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial on the safety and efficacy of continuous intratympanic dexamethasone delivered via a round window catheter for severe to profound sudden idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss after failure of systemic therapy. Laryngoscope 119(2):359–369. doi:10.1002/lary.20074

Ahn JH, Yoo MH, Yoon TH, Chung JW (2008) Can intratympanic dexamethasone added to systemic steroids improve hearing outcome in patients with sudden deafness? Laryngoscope 118(2):279–282. doi:10.1097/MLG.0b013e3181585428

Zhou Y, Zheng H, Zhang Q, Campione PA (2011) Early transtympanic steroid injection in patients with ‘poor prognosis’ idiopathic sensorineural sudden hearing loss. ORL 73(1):31–37. doi:10.1159/000322596

Wu HP, Chou YF, Yu SH, Wang CP, Hsu CJ, Chen PR (2011) Intratympanic steroid injections as a salvage treatment for sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Otol Neurotol 32(5):774–779. doi:10.1097/MAO.0b013e31821fbdd1

Lee JB, Choi SJ, Park K, Park HY, Choo OS, Choung YH (2011) The efficiency of intratympanic dexamethasone injection as a sequential treatment after initial systemic steroid therapy for sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 268(6):833–839. doi:10.1007/s00405-010-1476-8

Xenellis J, Papadimitriou N, Nikolopoulos T, Maragoudakis P, Segas J, Tzagaroulakis A, Ferekidis E (2006) Intratympanic steroid treatment in idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a control study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 134(6):940–945. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2005.03.081

Ho HG, Lin HC, Shu MT, Yang CC, Tsai HT (2004) Effectiveness of intratympanic dexamethasone injection in sudden-deafness patients as salvage treatment. The Laryngoscope 114(7):1184–1189. doi:10.1097/00005537-200407000-00010

Acknowlegments

No funding received for this work from any of the following organizations: NIH, Welcome Trust, HHMI or other.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lavigne, P., Lavigne, F. & Saliba, I. Intratympanic corticosteroids injections: a systematic review of literature. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 273, 2271–2278 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-015-3689-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-015-3689-3