Abstract

Cutaneous sarcomas are a heterogeneous group of rare mesenchymal neoplasms representing less than 1% of malignant tumors. Histology report remains the cornerstone for the diagnosis of these tumors. The most important clinicopathologic parameters related to prognosis include larger tumor size, high mitotic index, head and neck location, p53 mutations, depth of infiltration and histological grade, vascular and perineural invasion as well as the surgical margins status. Applying advanced biopsy techniques might offer more precise assessment of surgical margins, which constitutes a significant precondition for the management of these tumors. The management of cutaneous soft tissue sarcomas requires a multidisciplinary approach. Surgery remains the standard treatment, nonetheless adjuvant therapy may be required, consisting of radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and molecular targeted therapies to improve treatment outcomes. The role of molecular profiling in the treatment of uncontrolled disease is promising, but it may be offered to a relatively small proportion of patients and its use is still considered experimental in this setting. Due to the rarity of the disease, there is a need for knowledge and experience to be shared, pooled, organized and rationalized so that recent developments in medical science can have a major impact on the disease course. Multicenter clinical trials are needed to improve the care of patients with cutaneous sarcomas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cutaneous soft tissue sarcomas constitute a rare group of mesenchymal spindle cell neoplasms of the dermis and subcutis with large pathogenetic heterogeneity and represent less than 1% of malignant tumors [1]. DermatofibrosarcomaProtuberans (DFSP) constitutes the most common entity while other primary cutaneous neoplasms include Leiomyosarcoma (LMS), Malignant Undifferentiated Sarcomas (older term Malignant Fibrous Histiocytoma-MFH), Pleomorphic Dermal Sarcoma (PDS) (also known as Atypical Fibroxanthoma-AFX), Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS), Liposarcoma, Vascular Sarcomas (Cutaneous Angiosarcoma-CA) and Kaposi Sarcoma (KS), as well as some rare modalities, such as Myxoinflammatory Fibroblastic Sarcoma and Myxofibrosarcoma [2].

Histology remains the keystone for the diagnosis of these tumors. It should be noted that the exclusion of other dermal neoplasms such as melanoma is of exceptional importance, due to their possibly aggressive and malignant course. Genetics and molecular biology have revealed crucial aberrations in the natural history of these tumors. Thus, targeted therapies have been added to the therapeutic armamentarium of the clinicians dealing with cutaneous sarcomas [3].

Surgical excision ensuring negative surgical margins remains the mainstay οf local disease treatment. In the case of local recurrence or subtotal excision and when re-excision is not an option, radiotherapy (RT) and systemic chemotherapy can be employed. However, the ideal treatment algorithm in case of metastatic and/or recurrent disease is not defined in detail in the major treatment guidelines (European society for medical oncology—ESMO, National Comprehensive Cancer Network-NCCN) for the majority of these sarcomas.

Methods

A systematic literature review was performed based on database search in PubMed/MEDLINE and included articles up to July 2020. The terms used for the search were ‘Cutaneous’, ‘sarcomas’ and synonyms combined with one or more of the following: ‘factors’, ‘biopsy’, ‘chemotherapy’, ‘treatment’, ‘survival’, ‘recurrence’ and synonyms. Pre-clinical, clinical phase I, II, randomized phase III and IV studies, reviews, meta-analyses and abstracts of important meetings were analyzed. Articles published in English were included.

Results

Epidemiology, histopathologic profile and immunohistochemistry

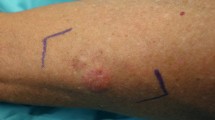

While the vast majority of cutaneous sarcomas usually affects elderly patients with their peak incidence in the 6th to 8th decade, DFSP is more likely to occur in early and middle adulthood [3]. Clinical presentation usually consists of a painless tumor, mostly observed in the trunk and proximal extremities [4]. Histological examination of DFSP reveals a proliferation of uniform spindle tumor cells incorporated into fibrous stroma that have minimal cytoplasm, indistinct margin and present minimal mitotic activity [5, 6]. The growth pattern of these tumor cells is characterized by asymmetry and a characteristic infiltration of subcutaneous fat, which resembles a honeycomb pattern [7]. Except for cutaneous and subcutaneous fat, the fascia, muscle, and bone may be also infiltrated by these tumors with lateral margins being distinctly larger than clinical in most of the cases [8]. Concerning the immunohistochemistry of these tumors, it should be mentioned that they exhibit positivity for CD34 and negativity for Factor XIIIa, which may be useful for the differentiation from other cutaneous sarcomas [9, 10]. DFSP is considered as a low malignant type, with a propensity to recur locally after resection. However, the prognosis is good with a 5-year relative survival rate up to 99% while its metastatic profile is fortunately very low [11]. Although there is no staging system for the prediction of clinical outcomes, some clinicopathologic parameters are more likely to predict the recurrence incidence and affect survival rates [5, 12]. Indeed, older age, male gender, larger tumor size, high mitotic index, head and neck location and p53 mutations seem to be associated with worse prognosis affecting both recurrence and survival. Identification of the translocation t(17;22) (q22;q13), which results in the formation of a fusion gene between beta-type platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFRB) gene and the collagen type 1 alpha1 (COL1A1) gene, is pathognomonic for this tumor type. Furthermore, it reveals that the activation of PDGFRB signaling pathway is crucial for the pathogenesis of DFSP. This molecular finding has offered the option of targeted therapies (imatinib) and potentially innovative immunotherapy approaches.

Similar to DFSP, Cutaneous Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) represents a rare dermal sarcoma accounting for less than 3% of dermal sarcomas that grow slowly [13]. In contrast to deep LMS, superficial ones are found in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue and present a lower metastatic rate, not exceeding 15% [13]. Given the more favorable prognosis for dermal LMS, it is worth mentioning that infiltration depth and histological grade may constitute prognostic factors for these tumors [14]. Cutaneous LMS is exhibited with an infiltrative growth pattern consisting of atypical spindle cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, nuclear atypia and multiple mitoses [14]. The diagnosis depends on findings of hemorrhagic and necrotic regions, atypical smooth muscle cells and the expression of the vimentin, α-smooth muscle actin, and desmin, that is observed in 60% of cases [17, 18]. With regard to their immuno-histochemical profile, these tumors present positivity for SMA, desmin, and h-caldesmon [19, 20]. Cutaneous LMS presents a locally aggressive behavior with estimated recurrence and survival rates after excision as high as 60% and 92%, respectively [21]. Indeed, researchers have noticed recurrences even after adequate resections with wide margins, of about 5 mm [22]. Except for the depth of infiltration and histological grade, other factors are considered to be important, including mitotic rate, necrosis, vascular invasion as well as tumor size [23]. In particular, it has been illustrated that tumors with size up to 2 cm compared to those larger than 5 cm exhibit survival rates of approximately 95% versus 30%, respectively [24].

Undifferentiated Sarcomas constitute approximately one-fifth of cutaneous soft tissue sarcomas when KS cases are not incorporated [15]. These tumors mostly occur in elderly males, in the head and neck region and extremities [25]. The histological profile of Undifferentiated Sarcoma includes short and ovoid spindle cells with a great number of mostly atypical mitoses. There is usually observed a great variety of cells (inflammatory, giants, macrophages) and regions with characteristic necrosis. With regard to immunohistochemistry, the majority of cases present positivity for XIIIa, SMA and CD68 and express the molecular markers desmin and CD34 [26]. Similar to other cutaneous sarcomas, undifferentiated sarcomas present locally aggressive behavior, which explains both the high recurrence rates, estimated between 30 and 71%, as well as their metastatic behavior that reaches approximately 40% of reported cases [27].

Regarding vascular sarcomas, Kaposi Sarcoma (KS) is the most frequent type of soft tissue sarcoma, accounting for approximately 70% of cases in the United States [21]. It is a locally aggressive tumor, strongly associated with the Human Herpes Virus 8 infection [28]. KS is commonly found in patients with immunodeficiency diseases, such as AIDS, affecting either lymph nodes or organs. Additionally, it mainly affects males and children in African countries where there is a significant association between morbidity and mortality [29]. The cellular nature of KS remains indistinguishable. The histopathological findings include spindle-shaped cells, vascular proliferation, erythrocytes blood cells and lymphoplasmacytic infiltration of these lesions [30]. Several markers are found positive in the immunochemistry, which are expressed by almost all of these spindle cells. Concerning the fact that both the lymphatic and vascular endothelium compose the spindle cells, both endothelial markers, such as CD31, CD34, ERG, FLI-1, and markers of lymphatic endothelium, such as vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (VEGFR3) and D2-40, are being expressed [31, 32]. However, it is noteworthy that there is still no effective therapy for the disease. Indeed, although highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART) has led to the reduction of the Kaposi Sarcoma incidence, no total regression has been observed yet [33]. RT, surgery and chemotherapy may complete the therapeutic approach of KS, while molecular targeted therapies are currently investigated.

Cutaneous Angiosarcomas (CA) constitute aggressive vascular tumors representing 2% of soft tissue sarcomas mostly found in the head and neck region of elderly individuals [34]. They are detected more frequently in males and the etiologic risk factors include history of prior radiation, chronic lymphedema after mastectomy in women and chronic skin exposure to ultraviolet light [35, 36]. CA are tumors composed of spindle cells with various differentiations [14]. Vascular channels with atypical endothelium are usually observed in well-differentiated tumors while lesions with increased mitoses and absence of erythrocytes are characteristics in high-grade tumors [37, 38]. The immuno-histochemical findings that are helpful in the diagnosis of CA include the expression of the markers CD31, CD34, ERG FLI-1 and cytokeratins [39]. Unlike other superficial sarcomas, CA has a poorer prognosis because of their propensity for early metastases through the blood stream to lungs, bone, liver or brain [40]. Studies have noted that the 5-year survival rate ranges from 20 to 45% [41]. Factors related to a poor prognosis include older age, tumor size larger than 45 mm, depth of invasion greater than 3 mm, higher mitotic rate, the anatomic region of the tumor (location on the head and neck have more favorable prognosis) as well as failure to achieve clear surgical margins [42]. Due to the presence of positive surgical margins in approximately 80–90% of reported cases, a generally high local recurrence rate is reported in the literature that exceeds 70% or even 80% [43].

Rare histologic subtypes of cutaneous sarcomas have also been described. Pleomorphic Dermal Sarcomas (PDS) are rare neoplasms mainly observed in the sun-exposed skin of the elderly [16]. The histological profile of PDS is characterized by pleomorphic, epithelioid, atypical spindle cells, combined with giant multinucleated tumor cells presenting frequent and atypical mitoses, including abnormal forms [14, 44]. PDS has a nodular, exophytic growth and despite the fact that they are often presented within the dermis, findings of subcutis or vascular invasion can be observed, indicating more aggressive tumor behavior [45]. Regarding the immuno-histochemical profile, most of the cases present positive reactions to CD34 and less frequently to SMA and EMA [46]. Although these tumors have a low metastatic profile, which is estimated lower than 5%, the presence of some factors, such as deep infiltration, necrosis, vascular and perineural invasion, is significantly associated with higher local recurrence and metastatic rates [47].

Lastly, other rare tumor types include Myxoinflammatory Fibroblastic Sarcoma and Myxofibrosarcoma. The former mostly appears in middle-aged individuals and presents high local recurrence rates [48]. The latter is a rare tumor which also has recurrence rates of 50–60%, regardless of histological grade. Additionally, those tumors with a more aggressive histological grade, are related to an increased metastatic profile ranging from 20 to 35% [49].

The role of histological examination

Improved histological examination constitutes a precondition for the enhanced management of these tumors. Fine-needle aspiration, core biopsy, incisional and excisional biopsy, are reliable biopsy techniques [50]. However, before the biopsy, several demographic and tumor-related factors, such as patient age and sex, tumor size and location, the subclinical extent of the tumor, the number of required surgical excisions for the achievement of clear surgical margins, as well as the depth of invasion and the esthetic outcome should be evaluated by clinicians [50].

The number of re-excisions and tumor growth pattern might predict tumor aggressiveness [51]. Several factors should be assessed through the examination of hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections with microscope. Characteristically, the tumor growth pattern, cellularity, cells’ appearance, amount and type of matrix formation, tumor and adjacent tissue interfaces, vascularity, tumor necrosis, and mitotic activity should be evaluated [50]. Excisional biopsies are usually required for the confirmation of smaller lesions and punch biopsies for larger ones [52]. The intraoperative frozen section biopsy may be useful for the evaluation of surgical margins. In the case of positive pathological results, either further excision or adjuvant RT is needed [53]. A re-excision is useful to fully determine the extent of horizontal, lateral and vertical tumor growth as well as the defect size of the tumor [51]. The intraoperative frozen analysis may effectively reveal surgical margins, thus leading to decreased rates of incomplete resections [54]. In the absence of this technique, both the extent of the tumor and the depth of invasion may be assessed by magnetic resonance (MR) imaging [53]. Furthermore, several studies reported better local control evaluation with the use of 3D histology, to assess both lateral and deep surgical margins [55]. The use of high-quality paraffin sections with 3D histology might deeply reveal subclinical extensions leading to reduced local recurrence rates and accordingly to better local control of the tumor [56].

Treatment options

The management of cutaneous soft tissue sarcomas requires a multidisciplinary approach. Surgery is the main therapeutic approach, which in combination with radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and molecular targeted therapies ensures the most favorable outcomes [57]. Multiple studies have widely described the significant association between clear surgical margins and lower recurrence rates, and accordingly better prognostic outcomes [58]. However, it should be mentioned that the anatomic region where the tumor is located (e.g., the head and neck region), is associated with better or worse outcomes, despite the fact that surgical resection margins are similar [57].

A wide local excision (WLE) or Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) may be applied to remove the lesion, although it is not well-defined which modality is superior to the other [58]. Obviously, factors, such as tumor characteristics and the existence of expertized clinicians, should always be taken into consideration before the final choice [59]. However, although WLE was traditionally used as the main treatment, MMS seems to be a more effective modality. Specifically, the reduction of surgical margins may offer a tissue-sparing advantage, which implies improved outcomes, both cosmetically and functionally [7]. MMS especially benefits more superficial lesions, where there is an increased cosmetic interest. Furthermore, its effective contribution to the reduction of recurrences is attributed to the fact that both deep and circumferential margins can be well assessed and evaluated by this approach, which is highlighted by multiple reviews and studies [62, 63]. Νonetheless, in case of inadequate surgical margins, repeated excisions, or in palliative occasions, RT, chemotherapy, and targeted therapies may be incorporated in the whole therapeutic procedure aiming to improve the prognosis of these patients [64].

Radiotherapy is described as more efficacious in larger and more aggressive tumors as well as in case of close margins, perineural invasion, or when there appears increased morbidity after a possible re-excision [65]. Several studies have described the beneficial role of RT in DFSP either preoperatively or as an adjuvant treatment in case of unclear surgical margins with good local control [66]. Doses of 50–70 Gy have been employed, with more recent studies showing that 50 Gy may be adequate [67]. Despite the fact that there are no forceful data about the role of RT in LMS, it should be considered in case of unclear margins and high-grade tumors with size larger than 5 cm [68].

The gold standard of treatment for undifferentiated sarcomas is the complete surgical resection, which may be accompanied by RT in case of unclear resection margins [15]. Additionally, given the management of patients with CA, apart from the clear benefit of adjuvant RT in large unresectable tumors, some studies also investigate the potentially favorable role of adjuvant chemotherapy in combination with targeted drug therapies to the improvement of poor survival of these patients [69]. Furthermore, regarding the rare modality of Myxofibrosarcoma that presents a high rate of local recurrence and poor prognosis, there are conflicting data about the role of RT because of the radio-resistant nature of these tumors [70]. On the contrary, RT may possess a valuable role in the case of unresectable or recurrent tumors in patients with PDS, which is well illustrated by several studies [71].

The role of chemotherapy in patients with both DFSP and LMS in the adjuvant setting is debatable. Nonetheless, chemotherapy might be beneficial for locally advanced high-risk tumors. In the case of metastasis, systemic therapy is given with palliative intent [72]. Both ESMO and NCCN guidelines describe the most efficacious therapeutic options for cutaneous sarcomas. Specifically, in advanced, unresectable, recurrent, or metastatic disease of DFSP, some studies highlight the role of targeted drug therapies such as imatinib [73,74,75]. In cases of metastasized LMS, conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy regimens used in soft tissue sarcomas are usually applied. For angiosarcomas, systemic treatment with taxane-based chemotherapy is currently used. However, promising results regarding the efficacy of immunotherapy agents to CA were recently published including anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody and tyrosine kinase inhibitors [76]. Finally, KS, when treated with chemotherapy systematically, liposomal doxorubicin, or paclitaxel, has shown positive results [77, 78].

Unfortunately, problems may arise from past management, due to short follow-up periods, retrospective and single-center experience data. To pool and enhance experience concerning sarcomas, more trials and data sharing are needed (phase 1b to phase 2 at least required). Cooperation will have a positive impact on time of accrual and diminished lead time biases. Informatics may also be useful in overcoming the problems of the past. Additionally, timing data sharing and cooperation will be useful in defining the role of different methods, such as molecular diagnostic and modern treatment procedures.

Conclusion

Cutaneous sarcomas are a heterogeneous group of rare mesenchymal neoplasms. The most common entities are DFSP, LMS, CA and KS. The histology report is important for the correct diagnosis of these tumors, while the exclusion of melanoma is crucial. Surgery remains the mainstay of therapy for patients with cutaneous sarcomas. Systemic treatment with RT, cytotoxic chemotherapy, targeted therapies and immunotherapy are offered to metastasized patients.

Multiple clinical trials are currently underway to evaluate novel therapies for sarcomas [79]. Despite an overall favorable prognosis, new therapeutic options, diagnostic and prognostic tools need to be developed to enhance the care for patients with cutaneous soft tissue sarcomas.

Availability of data and materials

Not needed.

Code availability

Not needed.

Abbreviations

- DFSP:

-

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans

- LMS:

-

Leiomyosarcoma

- PDS:

-

Pleomorphic dermal sarcoma

- AFX:

-

Atypical fibroxanthoma

- RMS:

-

Rhabdomyosarcoma

- CA:

-

Cutaneous angiosarcoma

- KS:

-

Kaposi sarcoma

- RT:

-

Radiotherapy

- PDGFRB:

-

Platelet-derived growth factor receptor

- VEGFR3:

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3

- HAART:

-

Highly active antiretroviral treatment

- MR:

-

Magnetic resonance

- WLE:

-

Wide local excision

- MMS:

-

Mohs micrographic surgery

References

Mentzel T (2011) Sarcomas of the skin in the elderly. Clin Dermatol 29(1):80–90

Wollina U, Koch A, Hansel G et al (2013) A 10-year analysis of cutaneous mesenchymal tumors (sarcomas and related entities) in a skin cancer center. Int J Dermatol 52(10):1189–1897

Maire G, Fraitag S, Galmiche L, Keslair F et al (2007) A clinical, histologic, and molecular study of 9 cases of congenital dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Arch Dermatol 143(2):203–210

Edelweiss M, Malpica A (2010) Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans of the vulva: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 13 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 34(3):393–400

Bowne WB, Antonescu CR, Leung DHY, Katz SC et al (2000) Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. A clinicopathologic analysis of patients treated and followed at a single institution. Cancer 88:2711–2720

Gloster HM Jr, Harris KR, Roenigk RK (1996) A comparison between Mohs micrographic surgery and a wide surgical excision for the treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. J Am Acad Dermatol 35:82–87

Llombart B, Serra-Guillén C, Monteagudo C, López Guerrero JA et al (2013) Dermatofibrosarcomaprotuberans: a comprehensive review and update on diagnosis and management. Semin Diagn Pathol 30(1):13–28

Guillen DR, Cockerell CJ (2001) Cutaneous and subcutaneous sarcomas. Clin Dermatol 19:262–268

Stranahan D, Cherpelis BS, Glass LF, Ladd S et al (2009) Immunohistochemical stains in Mohs surgery: a review. DermatolSurg 35:1023–1034

Haycox CL, Odland PB, Olbricht SM, Piepkorn M (1997) Immunohistochemical characterization of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with practical applications for diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol 37:438–444

Lemm D, Mügge LO, Mentzel T, Höffken K (2009) Current treatment options in dermatofibrosarcomaprotuberans. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 135:653–665

Takahira T, Oda Y, Tamiya S, Yamamoto H et al (2004) Microsatellite instability and p53 mutation associated with tumor progression in dermatofibrosarcomaprotuberans. Hum Pathol 35:240–245

Deneve JL, Messina JL, Bui MM, Marzban SS et al (2013) Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: treatment and outcomes with a standardized margin of resection. Cancer Control 20(4):307–312

Winchester DS, Hocker TL, Brewer JD et al (2014) Leiomyosarcoma of the skin: clinical, histopathologic, and prognostic factors that influence outcomes. J Am AcadDermatol 71(5):919–925

Hollmig ST, Sachdev R, Cockerell CJ, Posten W et al (2012) Spindle cell neoplasms encountered in dermatologic surgery: a review. Dermatol Surg 38(6):825–850

Beer TW, Drury P, Heenan PJ (2010) Atypical fibroxanthoma: a histological and immunohistochemical review of 171 cases. Am J Dermatopathol 32:533–540

Luzar B, Calonje E (2010) Morphological and immunohistochemical characteristics of atypical fibroxanthoma with a special emphasis on potential diagnostic pitfalls: a review. J Cutan Pathol 37:301–309

Evans HL, Smith JL (1980) Spindle cell squamous carcinomas and sarcoma-like tumors of the skin: ac comparative study of 38 cases. Cancer 45:2687–2697

Mathew RA, Schlauder SM, Calder KB, Morgan MB (2008) CD117 immunoreactivity in atypical fibroxanthoma. Am J Dermatopathol 30:34–36

Volpicelli ER, Fletcher CD (2012) Desmin and CD34 positivity in cellular fibrous histiocytoma: an immunohistochemical analysis of 100 cases. J Cutan Pathol 39(8):747–752

Rouhani P, Fletcher CDM, Devesa SS, Toro JR (2008) Cutaneous soft tissue sarcoma incidence patterns in the US. An analysis of 12,114 cases. Cancer 113:616–627

Fields JP, Helwig EB (1981) Leiomyosarcoma of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Cancer 47:156–169

Massi D, Beltrami G, Mela MM, Pertici M et al (2004) Prognosticfactors in soft tissue leiomyosarcoma of the extremities: a retrospective analysis of 42 cases. Eur J Surg Oncol 30:565–572

Lang RG Jr (2008) Textbook of Dermatologic Surgery. Malignant tumors of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Padova: Piccin Nuova Libraria. 435–70

Abou-Jaoude M, El Ali M (2009) Malignant fibrous histiocytoma: a case report and literature review. Int Surg 94:196–200

Anderson CE, Al-Nafussi A (2009) Spindle cell lesions of the head and neck: an overview and diagnostic approach. Diagn Histopathol 15:264–272

Peiper M, Zurakowski D, Knoefel WT, Izbicki JR (2004) Malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the extremities and trunk: an institutional review. Surgery 135:59–66

Dittmer DP, Damania B (2013) Kaposi sarcoma associated herpesvirus pathogenesis (KSHV)—an update. Curr Opin Virol 3(3):238–244

Parkin DM (2006) The global health burden of infection- associated cancers in the year 2002. Int J Cancer 118:3030–3044

Cassarino DS, DeRienzo DP, Barr RJ (2006) Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comprehensive clinicopathologic classification. Part Two J Cutan Pathol 33:261–279

Salmon PJM, Hussain W, Geisse JK, Grekin RC et al (2011) Sclerosing squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, an underemphasized locally aggressive variant: a 20-year experience. Dermatol Surg 37:664–670

Dotto JE, Glusac EJ (2006) P63 is a useful marker for cutaneous spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma. J CutanPathol 33:413–417

Nguyen HQ, Magaret AS, Kitahata MM, VanRompaey SE et al (2008) Persistent Kaposi sarcoma in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: characterizing the predictors of clinical response. AIDS 22(8):937–945

Buehler D, Rice SR, Moody JS, Rush P et al (2014) Angiosarcoma outcomes and prognostic factors, a 25-year single institution experience. Am J Clin Oncol 37:473–479

Cuccia F, Figlia V, Palmeri A, Verderame F et al (2017) Helical tomotherapy® is a safe and feasible technique for total scalp irradiation. Rare Tumors 9(1):6942

Mentzel T, Schildhaus HU, Palmedo G, Büttner R et al (2012) Post-radiation cutaneous angiosarcoma after treatment of breast carcinoma is characterized by MYC amplification in contrast to atypical vascular lesions after radiotherapy and control cases: clinicpathological, immunohistochemical and molecular analysis of 66 cases. Mod Pathol 25(1):75–85

Annest NM, Grekin SJ, Stone MS, Messingham MJ (2007) Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: a tumor of the head and neck. Dermatol Surg 33:528–533

Bernstein SB, Roenigk RK (1996) Leiomyosarcoma of the skin. Dermatol Surg 22:631–635

Cook TF, Fosko SW (1998) Unusual cutaneous malignancies. Semin Cutan Med Surg 17:114–132

Meis-Kindblom JM, Kindblom LG (1998) Angiosarcoma of soft tissue: a study of 80 cases. Am J SurgPathol 22:683–697

Wollina U, Hansel G, Schönlebe J, Averbeck M et al (2011) Cutaneous angiosarcoma is a rare aggressive malignant vascular tumour of the skin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 25:964–968

Mobini N (2009) Cutaneous epithelioid angiosarcoma: a neoplasm with potential pitfalls in diagnosis. J Cutan Pathol 36:362–369

Foote MC, Burmeister B, Burmeister E, Bayley G et al (2008) Desmoplastic melanoma: the role of radiotherapy in improving local control. ANZ J Surg 78:273–276

Sobanko JF, Meijer L, Nigra TP (2009) Epithelioid sarcoma: a review and update. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2(5):49–54

Mark RJ, Poen JC, Tran LM, Fu YS et al (1996) Angiosarcoma. A report of 67 patients and a review of the literature. Cancer 77(11):2400–2406

Pawlik TM, Paulino AF, McGinn CJ, Baker LH et al (2003) Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp: a multidisciplinary approach. Cancer 98:1716–1726

Miller K, Goodlad JR, Brenn T (2012) Pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: adverse histologic features predict aggressive behavior and allow distinction from atypical fibroxanthoma. Am J Surg Pathol 36(9):1317–1326

Lang JE, Dodd L, Martinez S, Brigman BE (2006) Case reports: acralmyxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma: a report of five cases and literature review. Clin Orthop Relat Res 445:254–260

Patt JC, Haines N (2016) Soft tissue sarcomas in skin: presentations and management. Semin Oncol 43(3):413–418

Choi JH, Ro JY (2018) Cutaneous spindle cell neoplasms: pattern-based diagnostic approach. Arch Pathol Lab Med 142(8):958–972

Welsch K, Breuninger H, Metzler G, Sickinger F et al (2018) Patterns of infiltration and local recurrences of various types of cutaneous sarcomasfollowing three-dimensional histology. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 16(12):1434–1442

Tan YG, Chia CS, Loh WL, Teo MC (2016) Single-institution review of managing dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. ANZ J Surg 86(5):372–376

Woo KJ, Bang SI, Mun GH, Oh KS et al (2016) Long-term outcomes of surgical treatment for dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans accordingto width of gross resection margin. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 69(3):395–401

Smith-Zagone MJ, Schwartz MR (2005) Frozen section of skin specimens. Arch Pathol Lab Med 129:1536–1543

Veronese F, Boggio P, Tiberio R, Gattoni M et al (2017) Wide local excision vs. Mohs Tübingen technique in the treatment of dermatofibrosarcomaprotuberans: a two-centre retrospective study and literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 31(12):2069–2076

Eberle FC, Kanyildiz M, Schnabl SM, Schulz C et al (2014) Three dimensional (3D) histology in daily routine: practical implementation and its evaluation. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 12(11):1028–1035

Ugurel S, Kortmann RD, Mohr P, Mentzel T et al (2013) Brief S2k guidelines-Dermatofibrosarcomaprotuberans. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 11(3):16–19

Lindner NJ, Scarborough MT, Powell GJ, Spanier S et al (1999) Revision surgery in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans of the trunk and extremities. Eur J Surg Oncol 25:392–397

Hamid R, Hafeez A, Darzi AM, Zaroo I et al (2013) Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: role of wide local excision. South Asian J Cancer 2:232–238

Kokkinos C, Sorkin T, Powell B (2014) To Mohs or not to Mohs. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 67(1):23–26

Meguerditchian AN, Wang J, Lema B, Kraybill WG et al (2010) Wide excision or Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of primary dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Am J Clin Oncol 33:300–303

Loghdey MS, Varma S, Rajpara SM, Al-Rawi H et al (2014) Mohs micrographic surgery for Dermatofibrosarcomaprotuberans (DFSP): a single-centre series of 76 patients treated by frozen-section Mohs micrographic surgery with a review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 67(10):1315–1321

Lowe GC, Onajin O, Baum CL, Otley CC et al (2017) A comparison of Mohs micrographic surgery and wide local excision for treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberanswith long-term follow-up: the mayo clinic experience. Dermatol Surg 43(1):98–106

Luke JJ, Keohan ML (2012) Advances in the systemic treatment of cutaneous sarcomas. SeminOncol 39(2):173–183. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminoncol.2012.01.004

Castle KO, Guadagnolo BA, Tsai CJ, Feig BW et al (2013) Dermatofibrosarcomaprotuberans: long-term outcomes of 53 patients treated with conservative surgery and radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 86(3):585–590

Sun LM, Wang CJ, Huang CC, Leung SW et al (2000) Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: treatment results of 35 cases. Radiother Oncol 57:175–181

Williams N, Morris CG, Kirwan JM, Dagan R et al (2014) Radiotherapy for dermatofibrosarcomaprotuberans. Am J ClinOncol 37(5):430–432

Starling J 3rd, Coldiron BM (2011) Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of cutaneous leiomyosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 64(6):1119–1122

Perez MC, Padhya TA, Messina JL, Jackson R et al (2013) Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a single-institution experience. Ann Surg Oncol 20(11):3391–3397

Iwata S, Yonemoto T, Araki A, Ikebe D et al (2014) Impact of infiltrative growth on the outcome of patients with undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma and myxofibrosarcoma. J Surg Oncol 110(6):707–711

Cooper JZ, Newman SR, Scott GA, Brown MD (2005) Metastasizing atypical fibroxanthoma (cutaneous malignant histiocytoma): report of five cases. Dermatol Surg 31(2):221–225

Ng A, Nishikawa H, Lander A, Grundy R (2005) Chemosensitivity in pediatric dermatofibrosarcomaprotuberans. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 27(2):100–102

Thway K, Noujaim J, Jones RL, Fisher C (2016) Dermatofibrosarcomaprotuberans: pathology, genetics, and potential therapeutic strategies. Ann Diagn Pathol 25:64–71

Tazzari M, Indio V, Vergani B, De Cecco L et al (2017) Adaptive immunity in fibrosarcomatous dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans and response to imatinib treatment. J Invest Dermatol 137(2):484–493

Miyagawa T, Kadono T, Kimura T, Saigusa R et al (2017) Pazopanibinduced a partial response in a patientwithmetastaticfibrosarcomatousdermatofibrosarcomaprotuberanswithoutgenetictranslocationsresistanttomesna, doxorubicin, ifosfamideanddacarbazinechemotherapyandgemcitabine-docetaxelchemotherapy. J Dermatol 44(3):e21–e22

Fujisawa Y, Yoshino K, Fujimura T, Nakamura Y et al (2018) Front Oncol 8:46

Bower M, Palfreeman A, Alfa-Wali M, Bunker C et al (2014) British HIV association guidelines for HIV-associated malignancies 2014. HIV Med 15(2):1–92

Busakhala N, Kigen G, Waako P, Strother RM et al (2019) Three year survival among patients with aids-related Kaposi sarcoma treated with chemotherapy and combination antiretroviral therapy at Moi teaching and referral hospital. Kenya Infect Agent Cancer 14:24

Dagan R, Morris CG, Zlotecki RA, Scarborough MT et al (2005) Radiotherapy in the treatment of dermatofibrosarcomaprotuberans. Am J Clin Oncol 28(6):537–539

Funding

The authors declare no sources of funding, financial or non-financial interests and all relationships that could have direct or potential influence or impart bias on the present work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization the review idea: AG, AD, MT, literature search: DM, IN, AK, data analysis: IB, NT, NC, writing—original draft preparation: DS, FC, FA, MM, writing review: RADM, GI, KK Supervision: MT.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Not needed.

Consent to participate

Not needed.

Consent for publication

Not needed.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gkantaifi, A., Diamantis, A., Mauri, D. et al. Cutaneous soft tissue sarcomas: survival-related factors. Arch Dermatol Res 314, 625–631 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-021-02268-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-021-02268-1