Abstract

Object

Surgical revascularization for moyamoya disease prevents cerebral ischemic attacks by improving cerebral blood flow (CBF). It is undetermined, however, how rapid increase in CBF affects chronic ischemic brain during the acute stage in childhood moyamoya disease.

Materials and methods

The present study includes nine consecutive cases of patients with childhood moyamoya disease (2~8 years old, 6.2 in average), who underwent superficial temporal artery–middle cerebral artery (STA–MCA) anastomosis on 17 hemispheres. We prospectively performed single-photon emission computed tomography 1 and 7 days after 17 surgeries. The follow-up period ranged from 12 to 37 months (24.9 in average).

Results

The outcome of 17 surgeries was excellent (disappearance of transient ischemic attack) in 14 hemispheres (82.4%) and good (reduction of transient ischemic attack) in three hemispheres (17.6%). No patient suffered peri-operative infarction, except for one (5.9%) manifesting as pseudolaminar necrosis in a part of the cerebral cortex supplied by STA–MCA bypass at the subacute stage, which did not affect his long-term neurological status. One patient (5.9%) presented with transient facial palsy due to hyperperfusion, which resolved within several days. No patient manifested permanent neurological deterioration during the follow-up period.

Conclusion

The STA–MCA anastomosis is a safe and effective treatment for childhood moyamoya disease. We recommend routine CBF measurement for avoiding surgical complications including both cerebral ischemia and hyperperfusion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Moyamoya disease is a chronic, occlusive cerebrovascular disease with unknown etiology characterized by bilateral steno-occlusive changes at the terminal portion of the internal carotid artery and an abnormal vascular network at the base of the brain [19]. Surgical revascularization for moyamoya disease is believed to prevent cerebral ischemic attacks by improving cerebral blood flow (CBF), and superficial temporal artery (STA)–middle cerebral artery (MCA) anastomosis with or without indirect pial synangiosis is generally employed as the standard surgical treatment for moyamoya disease [4, 9–11, 20].

The immediate improvement of cerebral hemodynamics by STA–MCA anastomosis is considered to be one of the major advantages of this procedure [9, 11] compared to the indirect pial synangiosis [1, 12, 13, 17, 18], the alternative treatment for pediatric moyamoya disease. However, it is undetermined how rapid increase in CBF affects chronic ischemic brain during the acute stage in childhood moyamoya disease. To address this issue, we prospectively performed N-isopropyl-p-[123I] iodoamphetamine single-photon emission computed tomography (123I-IMP-SPECT) within 1 week after STA–MCA anastomosis in nine consecutive cases with childhood moyamoya disease operated on 17 hemispheres. In this report, we sought to evaluate the outcome of STA–MCA anastomosis for childhood moyamoya disease, especially focusing on the neurological events during the acute stage including peri-operative ischemic complication and cerebral hyperperfusion.

Materials and methods

The present study includes nine consecutive patients (2~8 years old, mean 6.2) with childhood moyamoya disease operated on 17 hemispheres by the same surgeon (M.F.) in Tohoku University Hospital from November 2004 to November 2006. All patients were strictly followed up in our institute with the mean follow-up period of 24.9 months (12~37 months). All patients satisfied the diagnostic criteria of the Research Committee on Spontaneous Occlusion of the Circle of Willis of the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Japan, except for one patient with akin-moyamoya disease with neurofibromatosis type-I (case-1 in Table 1). All patients underwent STA–MCA anastomosis with encephalo-duro-myo-synangiosis (EDMS) and dural pedicle insertion [4]. The CBF was routinely measured by 123I-IMP-SPECT 1 and 7 days after surgery in all patients. The 1.5 or 3 T magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) were routinely performed 2 and 8 days after surgery. The MRI includes diffusion-weighted images (DWI), fluid attenuated inversion recovery, T1-/T2-weighted images, and T2*-weighted images.

Results

Among nine consecutive patients with 17 surgeries, all patients obtained the disappearance (six cases, 66.6%) or reduction of ischemic symptoms (three cases, 33.3%) during the follow-up period (Table 1). The outcome of 17 surgeries was excellent (disappearance of transient ischemic attack (TIA)) in 14 hemispheres (82.4%) and good (reduction of TIA) in three hemispheres (17.6%). No patients suffered from peri-operative cerebral infarction, except for one patient (5.9%) presenting with pseudolaminar necrosis in a part of cerebral cortex supplied by STA–MCA bypass at the subacute stage, which did not affect his long-term neurologic status (case-6). There were no radiological changes including cerebral infarction and hemorrhage in 17 operated hemispheres as well as in one hemisphere without surgery in nine cases during the follow-up period after discharge. The patency of STA–MCA bypass was confirmed in all 17 hemispheres by MRA after surgery. One patient (one hemisphere, 5.9%) suffered from transient left facial palsy due to postoperative cerebral hyperperfusion from 5 to 9 days after right STA–MCA anastomosis (case-4). The detail of this case was previously reported elsewhere [5]. One patient suffered from subcutaneous effusion (case-1), which spontaneously resolved without infectious sign within 1 month after surgery.

Representative cases

Case-2

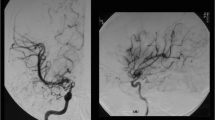

An 8-year-old girl presented with repeated TIA on her right hand and subsequent minor completed stroke. MRI on admission demonstrated cerebral infarction at the left occipital lobe with multiple ischemic changes at the bilateral paraventricular region, and MRA demonstrated steno-occlusive changes at the terminal portions of the bilateral internal carotid arteries as well as at the left posterior cerebral artery with the abnormal network-like vessels at the bilateral basal ganglia, which satisfied the diagnostic criteria for moyamoya disease [19]. The STA–MCA anastomosis with pial synangiosis was performed on the left hemisphere without complication. Postoperative 123I-IMP-SPECT showed significant increase in CBF on the operated hemisphere (Fig. 1b), and MRA/MRI demonstrated apparently patent STA–MCA bypass without ischemic change. She underwent right STA–MCA bypass 4 weeks later without complication, which also resulted in significant increase in CBF on the right hemisphere (Fig. 1c) with apparently patent STA–MCA bypass without ischemic change as shown by postoperative SPECT and MRA/MRI. Her TIA completely disappeared after surgery, and she did not suffer neurological deterioration during the follow-up period of 34 months. MRA 12 months after the initial surgery showed apparently patent STA–MCA bypass with significant development of pial synangiosis bilaterally (Fig. 2a).

Case-6

An 8-year-old boy presented with TIA on his left extremities and subsequent minor completed stroke. MRI on admission demonstrated cerebral infarction at the right parieto-occipital lobe, and MRA demonstrated steno-occlusive changes at the terminal portions of the bilateral internal carotid arteries and the presence of abnormal network-like vessels at the bilateral basal ganglia, which satisfied the diagnostic criteria for moyamoya disease [19]. The STA–MCA anastomosis with pial synangiosis was performed on the right hemisphere. The anastomosis was performed between the stump of the STA (0.8 mm in diameter) and the proximal portion of the M4 segment (0.8 mm in diameter) that supplied the frontal lobe. The 123I-IMP-SPECT 1 day after surgery showed no apparent change in CBF on the operated hemisphere compared to the pre-operative findings. Postoperative MRA showed the apparently patent STA–MCA bypass (Fig. 3a, arrow). Eight days after surgery, however, he suffered from severe monoparesis on his left hand when DWI demonstrated a linear high-intensity lesion at the right pre-central gyrus (arrow in Fig. 4a), which was not evident by the previous MRI (Fig. 4a). The use of anti-platelet agent and edaravone, a novel free radical scavenger, gradually relieved the symptom, and the linear high-intensity lesion by DWI disappeared 5 days later (Fig. 4c). His symptom returned to pre-operative status 3 months after the initial surgery. He underwent left STA–MCA anastomosis on the left hemisphere 4 months after initial surgery without complication. MRA 10 months after the initial surgery showed apparently patent STA–MCA bypass with significant development of pial synangiosis (arrow in Fig. 3b), when the right pre-central gyrus showed atrophic change, consistent with the pseudolaminar necrosis (arrows in Fig. 4d and h). There was no stroke during the follow-up period, and he obtained the improvement of TIA.

Case 6. MR imaging 1 day (a, e), 9 days (b, f), 14 days (c, g), and 10 months (d, h) after right STA–MCA anastomosis. Linear high signal intensity sign by DWI transiently appeared at pre-central gyrus 9 days after right STA–MCA anastomosis (arrow in b), where delayed atrophic change was evident 10 months after surgery (arrows in d, h), consistent with pseudolaminar necrosis

Discussion

The present study demonstrated the favorable outcome of STA–MCA anastomosis with routine postoperative CBF evaluation by SPECT in patients with childhood moyamoya disease (Table 1). Despite the safety and the long-term efficacy of STA–MCA anastomosis reported in the previous literatures [9–11, 20], a substantial number of children with moyamoya disease, as much as 59.3% of patients with STA–MCA anastomosis, were reported to suffer transient neurological deterioration during the acute stage after surgery [20]. The exact mechanism of this transient deterioration has been totally undetermined due to the lack of postoperative CBF analysis and MR study during the acute stage after STA–MCA anastomosis [20]. In our series, the final outcome of 17 surgeries was excellent (disappearance of TIA) in 14 hemispheres (82.4%) and good (reduction of TIA) in two hemispheres (17.6%). No patient suffered from permanent neurological deficit postoperatively, while two patients (11.8%) manifested transient neurological deterioration due to cerebral hyperperfusion in one patient (5.9%) and pseudolaminar necrosis in the other (5.9%), as diagnosed by the routine postoperative 123I-IMP-SPECT and MRA/MRI. Postoperative management based on these evaluations successfully led to the resolution of the symptoms. Thus, we recommend routine 123I-IMP-SPECT and MR angiography/imaging during the acute stage, as the clinical manifestation of hyperperfusion and ischemia is similar but the management of each condition is contradictory [4].

Postoperative hyperperfusion syndrome [8, 21] has been considered to be less common in patients with moyamoya disease [9, 10] due to the relatively low flow revascularization obtained by surgery for moyamoya disease. However, increasing evidences suggest that STA–MCA anastomosis for moyamoya disease, especially in adult cases, could also result in symptomatic cerebral hyperperfusion such as transient focal neurological deficit [4, 5, 7, 15] or delayed intracerebral hemorrhage [6]. The incidence of symptomatic hyperperfusion is as high as 38.2% in patients with adult-onset moyamoya disease [4], while the final outcome of these patients was excellent despite their temporary deterioration during the acute stage [4]. Contrary to adult-onset moyamoya disease, symptomatic hyperperfusion was reported only in a limited case among children [5], and the incidence of such phenomenon was undetermined among patients with childhood moyamoya disease. The present study indicated, for the first time, that the incidence of symptomatic cerebral hyperperfusion was 5.9% in childhood moyamoya disease, which was much lower that that of adult-onset moyamoya disease [4]. The reason why adult-onset patients are more vulnerable to cerebral hyperperfusion is totally undetermined. Certain biological background in adult patients may contribute to the high incidence of symptomatic hyperperfusion, and this issue remained to be elucidated in the future study.

Long-term follow-up of the neurological function including cognitive functions and the anatomical changes in the affected brain is needed, because exposure to sublethal levels of reactive oxygen species during reperfusion to the chronic ischemic brain can affect organelles, and thus lead to delayed neuronal damage by apoptosis [2, 3]. In fact, case-6 manifested as delayed pseudolaminar necrosis in a part of the cerebral cortex supplied by STA–MCA bypass at the subacute stage, suggesting the involvement of reperfusion injury. Besides this particular case, however, no patient in this series showed delayed cortical damages such as the expansion of cerebral infarction and the atrophic change at the chronic stage. Postoperative cerebral hyperperfusion could also be associated with impairment of cognitive function in patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy [16], which was reported to be prevented by pre-administration of a free radical scavenger [14]. Thus, we use edaravone, a novel free radical scavenger [14], to counteract the deleterious effect of reperfusion into the chronic ischemic brain of moyamoya patients during the acute stage. Further evaluation is necessary to clarify the underlying mechanism of both pseudolaminar necrosis and cerebral hyperperfusion after STA–MCA anastomosis in childhood moyamoya disease in a future study.

Conclusion

The STA–MCA anastomosis is a safe and effective treatment for pediatric moyamoya disease, although it has a substantial risk for cerebral hyperperfusion and delayed cortical damage such as pseudolaminar necrosis. We recommend routine CBF measurement for the differential diagnosis between cerebral hyperperfusion and ischemic attack, as the treatments for these conditions are contradictory.

References

Choi JU, Kim DS, Kim EY, Lee KC (1997) Natural history of moyamoya disease: comparison of activity of daily living in surgery and non surgery groups. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 99(Suppl 2):S11–S18

Fujimura M, Morita-Fujimura Y, Noshita N, Sugawara T, Kawase M, Chan PH (2000) Cytosolic antioxidant copper, zinc-superoxide dismutase prevents the early release of mitochondrial cytochrome c in ischemic brain after transient focal cerebral ischemia in mice. J Neurosci 20:2817–2824

Fujimura M, Tominaga T, Chan PH (2005) Neuroprotective effect of antioxidant in cerebral ischemia: role of neuronal apoptosis. Neurocrit Care 2:59–66

Fujimura M, Kaneta T, Mugikura S, Shimizu H, Tominaga T (2007) Temporary neurologic deterioration due to cerebral hyperperfusion after superficial temporal artery–middle cerebral artery anastomosis in patients with adult-onset moyamoya disease. Surg Neurol 67:273–282

Fujimura M, Kaneta T, Shimizu H, Tominaga T (2007) Symptomatic hyperperfusion after superficial temporal artery–middle cerebral artery anastomosis in a child with moyamoya disease. Childs Nerv Syst 23:1195–1198

Fujimura M, Shimizu H, Mugikura S, Tominaga T (2008) Delayed intracerebral hemorrhage after superficial temporal artery–middle cerebral artery anastomosis in a patients with moyamoya disease: possible involvement of cerebral hyperperfusion and increased vascular permeability. Surg Neurol (in press)

Furuya K, Kawahara N, Morita A, Momose T, Aoki S, Kirino T (2004) Focal hyperperfusion after superficial temporal artery–middle cerebral artery anastomosis in a patient with moyamoya disease. Case report. J Neurosurg 100:128–132

Heros RC, Scott RM, Ackerman RH, Conner ES (1984) Temporary neurological deterioration after extracranial–intracranial bypass. Neurosurgery 15:178–185

Houkin K, Ishikawa T, Yoshimoto T, Abe H (1997) Direct and indirect revascularization for moyamoya disease: surgical techniques and peri-operative complications. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 99(Suppl 2):S142–145

Houkin K, Nonaka T, Baba T (2005) Peri-operative complications in surgical treatment for moyamoya disease. Annual report 2004 by the Research Committee on Spontaneous Occlusion of the Circle of Willis (moyamoya disease), pp 47–50

Ishikawa T, Houkin K, Kamiyama H, Abe H (1997) Effects of surgical revascularization on outcome of patients with pediatric moyamoya disease. Stroke 28:1170–1173

Kim SK, Wang KC, Kim IO, Lee DS, Cho BK (2002) Combined encephaloduroarteriosynangiosis and bifrontal encephalogaleo(periosteal)synangiosis in pediatric moyamoya disease. Neurosurgery 50:88–96

Matsushima T, Inoue TK, Suzuki SO, Inoue T, Ikezaki K, Fukui M (1997) Surgical techniques and the results of a fronto-temporo-parietal combined indirect bypass procedure for children with moyamoya disease: a comparison with the results of encephalo-duro-arterio-synangiosis alone. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 99(Suppl 2):S123–S127

Ogasawara K, Inoue T, Kobayashi M, Endo H, Fukuda T, Ogawa A (2004) Pretreatment with the free radical scavenger edaravone prevents cerebral hyperperfusion after carotid endarterectomy. Neurosurgery 55:1060–1067

Ogasawara K, Komoribayashi N, Kobayashi M, Fukuda T, Inoue T, Yamada K, Ogawa A (2005) Neural damage caused by cerebral hyperperfusion after arterial bypass surgery in a patient with moyamoya disease: case report. Neurosurgery 56:E1380

Ogasawara K, Yamadate K, Kobayashi M, Endo H, Fukuda T, Yoshida K, Terasaki K, Inoue T, Ogawa A (2005) Postoperative cerebral hyperperfusion associated with impaired cognitive function in patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy. J Neurosurg 102:38–44

Scott RM, Smith JL, Robertson RL, Madsen JR, Soriano SG, Rockoff MA (2004) Long-term outcome in children with moyamoya syndrome after cranial revascularization by pial synangiosis. J Neurosurg 100(2 Suppl Pediatrics):142–149

Shirane R, Yoshida Y, Takahashi T, Yoshimoto T (1997) Assessment of encephalo-galeo-myo-synangiosis with dural pedicle insertion in childhood moyamoya disease: characteristics of cerebral blood flow and oxygen metabolism. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 99(Suppl 2):S79–S85

Suzuki J, Takaku A (1969) Cerebrovascular ‘moyamoya’ disease. Disease showing abnormal net-like vessels in base of brain. Arch Neurol 20:288–299

Taki W, Tanaka M, Miyamoto S, Nagata I, Kikuchi H (1995) Postoperative transient neurological deficit in children with moyamoya disease. Annual report 1994 by the Research Committee on Spontaneous Occlusion of the Circle of Willis (moyamoya disease), pp 88–93

van Mook R, Rennenberg G, Schurink R, van Oostenbrugge W, Mess P, Hofman P (2005) Cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome. Lancet Neurol 4:877–888

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fujimura, M., Kaneta, T. & Tominaga, T. Efficacy of superficial temporal artery–middle cerebral artery anastomosis with routine postoperative cerebral blood flow measurement during the acute stage in childhood moyamoya disease. Childs Nerv Syst 24, 827–832 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-007-0551-y

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-007-0551-y