Abstract

To look for the spectrum of infections and the factors predisposing to infection in patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc). In this retrospective study, demographic, clinical features, details of infections, immunosuppressive therapy, and outcomes of patients with SSc attending clinics at department of Clinical Immunology and Rheumatology, Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow, India from 1990 to 2022 were captured. Multivariable-adjusted logistic regression was applied to identify independent predictors of infection. Data of 880 patients, mean age 35.5 ± 12 years, and female: male ratio 7.7:1, were analyzed. One hundred and fifty-three patients had at least 1 infection with a total of 233 infectious episodes. Infections were most common in lung followed by skin and soft tissue. Tuberculosis was diagnosed in 45 patients (29.4%). Klebsiella was the commonest non-tubercular organism in lung and Escherichia coli in urinary tract infections. In comparison to matched control group, patients with infection had a greater number of admissions due to active disease, odds ratio (OR) 6.27 (CI 3.23–12.18), were receiving immunosuppressive medication OR, 5.05 (CI 2.55–10.00), and had more digital ulcers OR, 2.53 (CI 1.17–5.45). Patients who had infection had more likelihood for death OR, 13.63 (CI 4.75 -39.18). Tuberculosis is the commonest infection and lung remains the major site of infection in patients with SSc. Number of hospital admissions, digital ulcers and immunosuppressive therapy are predictors of serious infection in patients with SSc. Patients with infections had more likelihood of death.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Systemic sclerosis [SSc] is a complex chronic autoimmune connective tissue disease characterized by vasculopathy, abnormal and excessive deposition of extracellular matrix in the skin and internal organs, and the presence of autoantibodies. [1, 2] Patients with SSc have increased susceptibility to infections, primarily stemming from the disease itself and its associated complications. The presence of interstitial lung disease [ILD] [3], digital ulcers [DU], and calcinosis contribute to increased risk of respiratory and skin infections [4]. Additionally, the increased use of immunosuppression in the management of SSc further heightens the risk of infections. However, recent trials with Tocilizumab [TCZ] [5, 6], Cyclophosphamide [7] and Abatacept [ABA] [8] in SSc did not report an increased risk of infections.

Among rheumatic diseases, SSc has the highest standardized mortality ratio [SMR], indicating a greater risk of death in comparison to the general population [9]. A meta-analysis conducted until 2006 revealed a SMR of 3.53 among patients with SSc [10]. However, emerging evidence suggests that non-systemic sclerosis [non-SSc]-related causes account for a substantial proportion of both mortality and hospital admissions in SSc patients, approaching 50% in recent studies. Among these non-SSc-related causes, infections are a significant contributing factor [10,11,12,13,14]. A study conducted by Chung et al. between 2002 and 2003 demonstrated that infections ranked among the top three causes of mortality in SSc patients, approximating 13% of fatal events [15]. In contrast, a study conducted by Poudel et al. a decade later [2012–2013] revealed that among deceased patients with SSc, the most frequent diagnoses were; infection [32.7%], pulmonary involvement [20%], and cardiovascular events [15.7%]. The study also found that non-opportunistic infections had a significantly high adjusted odds ratio [OR] for death [3.36, 95% confidence interval 2.73–4.41] [16].

While infections in SSc are acknowledged, comprehensive characterization of infection types, predictors of serious infections, and their impact on outcomes is less explored in the literature. Identifying such predictors of infections can aid in close monitoring, early intervention, and appropriate management strategies to mitigate serious infection risks. The present study focuses on one of the largest cohorts of SSc patients from India, providing insights that may differ from studies carried out in the West or in different ethnic populations. Findings from this study could potentially affect clinical practice.

The present study is a retrospective audit of clinic files aimed to characterize the spectrum of infections in Cohort of SSc in xxxxxx[xxxxx],xxx, and to identify predictors of serious infections and their influence on patient outcomes.

Methods

We analyzed data from a cohort of SSc patients who visited our hospital between May 1990 and December 2019. Diagnosis of SSc were based on either 1980 ARA criteria [17] or 2013 ACR/EULAR classification criteria for Systemic sclerosis [18]. This is a retrospective study, and data was collected from both case files and electronic health information system. The attending physician entered data directly into case files during each outpatient department (OPD) visit, while details of admission and the course of hospitalization in the inpatient department (IPD) were recorded by the treating doctor, fellow-in-training, in electronic health records. Patients were followed up at every two to three months intervals. The following data were recorded; clinical features and laboratory test results [including complete blood count, renal function, liver functions, and pulmonary function tests] and imaging on a case-to-case basis. Baseline information including demographics, affected organs, and extent of disease [as measured by mRSS, pulmonary function tests] were collected. Data regarding serious infections, immunosuppressive therapy, patient outcomes, and complications were recorded. A comparison of demographic, clinical, laboratory and treatment variables was conducted between SSc patients with infection and age and sex-matched SSc control group without infection, to identify predictors of infection.

Infections that necessitated hospital admission, intravenous antibiotics, or resulted in disability or mortality were classified as serious [7, 19]. The treating rheumatologist identified infections based on their clinical judgment and supportive evidence, such as culture from the affected body fluids/tissue, serological positivity to a pathogen, polymerase chain reaction [PCR], or imaging evidence of infection. As the global COVID-19 infection affected the study population, it was not included in this analysis. Data regarding in-patient deaths were collected from the hospital electronic records, while information on out-patient mortality was obtained from patient's family, which was documented in the hospital clinic records.

Ethics

As this study was retrospective in nature, the ethics committee reviewed our research protocol and determined that obtaining informed consent from participants was not required. This exemption was granted based on the fact that the study involved analysis of data from the clinic files and electronic health records over more than three decades and did not require contact with the patients. The ethics committee's decision was documented in the approval letter with protocol number PGI/BE/129/2020, dated 21st February, from the Institutional Ethics committee, SGPGI.

Statistics

Baseline findings were presented as median [IQR] for numerical variables and percentage for categorical data. Continuous variables were interpreted using parametric student’s T-test, while categorical data were assessed using the Chi-square test or Fischer’s exact test.

We utilized multivariable-adjusted logistic regression to identify predictors of serious infection, including disease duration, organs involved, disease activity, immunosuppressive treatment, number of hospital admissions, and others. The impact of serious infection on mortality was analyzed. Statistical analysis was carried out on IBM SPSS v26.

Results

Demographics

A total of 880 patients were included in the study, with a female-to-male ratio of 7.7:1 [779 females and 101 males]. The mean age at diagnosis was 35.5 ± 12 years [ranging from 6 to 70 years]. The median duration of illness before diagnosis was 24 months [Interquartile range/IQR 12 to 60]. 323[36.7%] patients were admitted for in-patient care. Furthermore, 293[33.3%] patients had at least one admission specifically for active disease management.

The total duration of follow-up for all patients combined was 3029.33 person-years. The median follow-up duration per patient was 471.5 days [IQR ranging from 28 to 1830 days]. Most common disease subset was diffuse SSc [dSSc] [517(58.75%)], followed by limited SSc [lSSc] [283(32.1%)] whereas the rest 80 [9.1%] had sine scleroderma.

Clinical characteristics

Skin is the most common organ involved with median modified Rodnan Skin Score (mRSS) of 16 [7 to 26 IQR]. 80 [9.1%] patients had no skin involvement and 43[4.9%] patients had extensive skin involvement with mRSS more than 40. Raynaud phenomenon was the most common clinical sign present in 90.9% of patients and progressed to gangrene in 79 patients [9%]. Digital ulcers were reported by 445 [50.6%] patients at some point in their disease course. Among the musculoskeletal symptoms, 273[31%] patients had inflammatory arthritis, 92 [10.5%] patients developed myositis, and calcinosis was noted in 36 [4.1%] patients. Sicca symptoms were present in 35 patients [4%]. Dyspepsia, abdominal bloating, and poor appetite were present in 504 [57.3%] patients.

Major organs involved were; interstitial lung disease [ILD] in 452 [51.4%], pulmonary arterial hypertension [PAH] in 175 [19.9%], scleroderma renal crisis in 27 [3.06%], and cardiac involvement in 51 [5.8%] patients.

Infections

Out of 880 patients, 153 patients [17.4%] experienced at least one infection during the illness. Among these individuals, 46 patients [5.2% of the total] had recurrent infections. Among the patients who experienced infections, the lung was the most common site, accounting for 46.3% [71/153] of the cases. Additionally, infections affecting the skin and soft tissue [SSTI] were also prevalent, representing 21.8% [51/233] of the cases. Urinary tract infection [UTI] was noted in 9.8% [23/233] of patients. Seven patients had fungal infection [Table 1] 12 patients had a viral infection, 50% of which were due to herpes zoster.

Tuberculosis [TB] was the most common infection in the lungs accounting for one-third of all infections. A total of 45 [5.1%] patients had tuberculosis which was limited to lung in 25 patients, extrapulmonary TB was diagnosed in 17 patients, and 9 of them presented with TB lymphadenitis. Three patients had disseminated tuberculosis [Table 2].

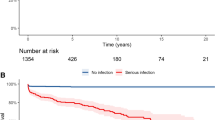

After tuberculosis, Klebsiella pneumoniae was the second most common organism isolated from lung infection. A total of 12 patients had Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated, 2/3rd of them from sputum culture. 15% [23/153] of patients with infection had UTI requiring admission with 52.2% [12/23] of these being due to Escherichia coli. Staphylococcus aureus was the most common organism isolated from skin and soft tissue [45.5% [15/33] of culture-proven SSTI]. Pseudomonas aeruginosa was implicated in 7 patients and Streptococcus pneumoniae in 6 patients. Enterococcus species was isolated from 5 patients [Table 2 and Fig. 1]. Uncommon infections included 1 patient with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy [PMLE] [radiological diagnosis] and Citrobacter freundii osteomyelitis.

Common infectious organisms and source of isolation. #SSTI: Skin and soft tissue, GI: Gastrointestinal tract, UTI: Urinary tract infection; Few uncommon infections in our cohort included, Dengue and Aspergillus in 2 patients each, Hepatitis C in 3 patients, malaria, Acinetobacter, Citrobacter, Hemophilus influenzae, Proteus mirabilis, Chicken pox, Neisseria and Salmonella typhi in 1 patient each

Mortality

There was a total of 45 in-hospital deaths due to infection. More than one-third of deaths were secondary to lung involvement with pneumonia accounting for 19 deaths. Seven deaths were attributed to gastrointestinal tract [GIT] infection, six to malignancy, and four deaths were attributed to congestive heart failure. Infections had an odds ratio of 13.63 [95% CI 4.74 to 39.18], for mortality.

Immunosuppressive medications

In the present study, in SSc with infection group, 23 out of 52 patients had received more than one immunosuppressant during the illness. Most frequently used immunosuppressants were cyclophosphamide, MMF, Tacrolimus, Methotrexate and Rituximab [Table 3]. Low-dose Prednisolone [≤ 7.5 mg/day] was used in patients with inflammatory arthritis/myositis /serositis for the shortest period with either gradual tapering and discontinuation or continued at 0.1 mg/kg/day as maintenance dose. Cumulative/average dose of prednisolone was not captured. As a policy, we never used pulse methylprednisolone for the risk of SRC.

Autoantibodies

Antinuclear antibodies [ANA] were positive in 91.2% of patients tested [n = 654 patients]. ANA was negative in 56 patients; centromere pattern was present in 21 patients. Most common autoantibody detected was anti-Scl 70 [59%, 324/552] and anti-centromere was detected in 4% patients among patients who were tested for anti-extractable nuclear antigen [ENA].

A comparison between SSc patients with infection and SSc patients without infection, matched for age and gender, was carried out. While patients with infection had more hospital admissions, they also had more admissions for active disease management with an odds ratio of 6.27 [3.23 to 12.18] [Table 4]. Patients with infection had longer follow-up durations and shorter time intervals from symptom onset to diagnosis. Presence of Raynaud phenomenon, DU, GERD, sicca symptoms, presence of ILD or PAH, and history of SRC showed statistically significant risk of having infection in univariate analysis [Table 4]. Patients who contracted infection had higher mRSS as compared to the control group. However, in multivariable-adjusted analysis, total number of admissions, patients with DU, and those receiving or had received immunosuppressive treatment ever had a significantly predicted risk of infection [Table 5].

Discussion

Data from the present study indicated that infections particularly of lung, skin and soft tissue, and urinary tract are commonly observed in patients with SSc. Amongst lung infections, Mycobacterium tuberculosis predominates over other bacterial, viral and fungal infections. In addition, the locally defective barriers in the skin from DU or pre-existing lung pathology from ILD resulted in infections. The patients who had a high prevalence of DU, arthritis, and ILD indicated that most of them had active disease as well as severe SSc [more prevalent ILD, PAH, SRC]—resulting in a greater number of hospital admissions and frequent use of immunosuppressants, ± corticosteroids, which might have predisposed to infections. Patients who had infection tend to remain on follow-up for a greater length of time. They also had more symptomatic disease as suggested by a shorter interval for making a diagnosis from the time of symptom onset.

Lung is the most common site of infectious complications in most series, involving up to 24% of the events [1] possibly due to ILD, which is seen in almost 50–60% of SSc patients and is one of the leading causes of death in many series [20]. Around 40% of these deaths are due to lung infection [21]. In our cohort, lung infection was the most common site accounting for 46.3% of cases with tuberculosis followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae being the most frequently isolated organisms. Earlier studies from Taiwan had reported risk of tuberculosis in SSc is 2.81 times for TB overall and 2.53 for pulmonary TB [22, 23]. Age more than 60 years, and PAH were associated with increased risk of tuberculosis. SSc was a risk for TB and has hazard ratio of 2.99 [95 CI 1.58–5.63]. A study by Hsu et al. investigating the burden of opportunistic infections in rheumatic diseases found an incidence ratio (IR) of 31.6 per 1000 person-years in SSc [24]. Specifically, herpes zoster, candidiasis, and tuberculosis had IRs of 19.9, 4.51, and 4.32 per 1000 person-years, respectively. The risk of opportunistic infections was highest in the first year following the diagnosis [24]. Among patients who received dexamethasone pulse therapy, pulmonary TB was seen in 9% and extrapulmonary TB in 20% [25]. We had 45 patients with tuberculosis, with 44.4% of infections being extrapulmonary. We also observed that patients who had TB were younger and had a greater number of infections compared to those who had non-tubercular infections. Such a high frequency of Tuberculosis in our series may be due to high endemicity of tuberculosis in India. According to a World Health Organization report, in 2021, eight countries represented over two-thirds of global TB cases with India [28%] contributing the highest number of cases [26]. Another reason could be immunosuppressive treatment, which predisposes towards a greater risk of reactivation of TB, and finally, non-affordability of treatment drugs by those who are infected due to poverty. All these reasons might have contributed to high TB prevalence in our cohort.

The issue of screening for latent tuberculosis in patients with SSc remains unresolved till date as skin thickening is likely to affect the result of tuberculin skin test and there is no gold standard cut off to predict positive test. Out of 45 patients with TB in our cohort, only 15 were screened for latent TB before starting immunosuppressive drugs. There was not a uniform policy to screen for latent TB in our unit till 2015 and 40 out of 45 patients with TB belonged to this period. A total of 636 patients were enrolled in the cohort during this period. After 2015 screening for latent TB was practiced routinely, a total of 244 patients were added to our cohort and only 5 patients developed TB. Thus, it may be prudent to point out that screening for latent TB should be a mandatory clinical practice in patients with SSc even in endemic countries like India as it is likely to bring down the incidence of TB and affect the consequent morbidity and mortality.

Breach in skin due to any cause and that too in an ischemic environment is a perfect recipe for difficult-to-treat infection and patients with DU tend to have ulcers lingering on for few weeks or even months. In a Turkish study, presence of digital ulcers [OR 2.85(1.36–5.89)] and cardiac involvement [OR 2.80(1.25–6.29)] were associated with increased risk of serious infection [27]. At times, DU infections can progress to deeper tissues like bone and may cause osteomyelitis. The incidence of osteomyelitis may reach 8%, escalating to 17% among patients with active DU, and surging to 42% if any signs of infection like pus discharge or fever are present [4, 28,29,30]. Similar to our study, other study has also reported the most common organisms as Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [31]. We had a patient with osteomyelitis of a distal phalange secondary to Citrobacter freundii. She in addition had gangrene, DU, mRSS of 33 and required cervical sympathectomy. Chronic administration of low-dose corticosteroids has been reported to predispose to infections caused by pyogenic bacteria; staphylococcus, streptococcus and enterobacteriaceae [32]. However, in the present study the number of patients ever exposed to or were receiving prednisolone at the time of infection was not different between the infection vs non-infection groups. Therefore, role of corticosteroids in predisposing to bacterial infections in the present study seems less likely.

A high incidence of esophageal candidiasis in SSc patients being treated with proton pump inhibitors [PPIs] was reported [33, 34]. Compromised esophageal motility, which is a common gastrointestinal [GI] feature of SSc, might create a favourable environment for the overgrowth of Candida, leading to the development of candidiasis. This was uncommonly reported in recent years, yet we had 3 patients with esophageal candidiasis in our cohort. Therefore, it is worth noting that the continuous usage of proton pump inhibitors [PPIs] and antibiotics for bacterial overgrowth are factors that should be implicated as potential risks for infection in SSc patients [1].

In scleroderma lung study, five cases of pneumonia were reported in the cyclophosphamide arm as against one in the placebo arm in the first 1 year of treatment [35]. Cyclophosphamide has been described as a low-risk drug for predisposing to PMLE [progressive multifocal leuko-encephalopathy] which was diagnosed in one patient who had to be treated with intravenous immunoglobulin [IVIG] [36]. A recent meta-analysis of cyclophosphamide compared with mycophenolate mofetil [MMF] in ILD found no difference in pneumonia rates between the two [37,38,39]. We noted that patients on immunosuppressive medications tend to develop infection more as compared to those who did not receive any immunosuppressive therapy.

A study of serious infection with systemic sclerosis in the US population had most presentations with pneumonia in 45% of patients similar to the present study. Sepsis was noted in 32% of patients while it was less in our study [40].

Two comprehensive meta-analyses, encompassing data from the 1960s to the first decade of the 2000s, highlighted that infections accounted for approximately 7% of deaths in individuals with SSc [10, 41]. A French study reported that patients with SSc had a five times higher risk of infection-related deaths in comparison to general population [42]. In our study, 1/3rd of deaths were due to infection with lung infection being implicated in 50% of these cases. Thus, high index of suspicion especially in patients with risk factors of susceptibility to infection, early diagnosis and treatment may minimize risk of mortality. Given the high frequency of TB in the present study, we recommend following screening protocol for latent TB as per local guidelines before initiation of immunosuppressive medications, more so for countries like India where endemicity of TB is high. Patients on corticosteroids should be screened with interferon gamma release assays as corticosteroids are known to mask tubercular skin testing [43].

The strengths of our study are its size and its expansion over a wide period of more than three decades. With the help of electronic health records, the bulk of the information regarding admissions, indications for admissions, outcomes and laboratory parameters were available for most of the patients.

Limitations of the study are that it is a retrospective study where some of the data is missing when electronic health records were not robust before the year 2000. Many deaths outside the hospital settings might have been caused by infections, details of which could not be documented in some cases due to recall bias of the relative providing information about the death. We did not have access to death certificates of these patients issued either by practitioners/hospitals or by the state/national authorities. Though corticosteroids have been sparingly used in our unit ever since its inception still information about low dose corticosteroids was not captured in the study. Even low-dose corticosteroids may increase susceptibility to infections if used over a prolonged period.

Conclusion

Patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc) are particularly susceptible to infections in the lungs, skin, soft tissues, and urinary tract. Tuberculosis, both pulmonary and extra-pulmonary, is notably prevalent, followed by pyogenic bacterial pneumonias and urinary tract infections (UTIs). Our study identifies the number of hospital admissions, the presence of DU, and the use of immunosuppressive therapy as key predictors of serious infections in SSc patients. Furthermore, infections constitute a significant cause of mortality within this patient population.

Perspectives and gaps in research

For clinicians, regular monitoring for infections, early detection, managing risk factors like frequent hospital admissions, digital ulcers, and immunosuppressive therapy, implementing preventive measures such as vaccinations and prophylactic antibiotics, and adopting a multidisciplinary approach can improve patient outcomes. For researchers, identifying additional predictors, investigating underlying mechanisms, identification of biomarkers of early infections, evaluating the impact of immunosuppressive therapies, and encouraging data sharing and collaborative research are key to enhancing infection management strategies and advancing knowledge in systemic sclerosis.

Disclaimer

-

1.

No part of this manuscript is copied or published elsewhere. No part of this study has been presented in any national or international conferences but was accepted for publishing in EULAR 2024.

Abhishek GP, Ahmed S, Agarwal V (2024) AB1185 Serious infections in systemic sclerosis: a single centre data of 30 years. Ann he Rheum Dis 83:1928. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2024-eular.5140

Data availability

Data pertaining to this study is available with the corresponding author and will be shared on reasonable request.

References

Barahona-Correa JE, De la Hoz A, López MJ, Garzón J, Allanore Y, Quintana-López G (2020) Infections and systemic sclerosis: an emerging challenge. Revista Colombiana de Reumatología (English Edition) 27:62–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcreue.2019.12.004

Rongioletti F, Ferreli C, Atzori L, Bottoni U, Soda G (2018) Scleroderma with an update about clinico-pathological correlation—Giornale italiano di dermatologia e venereologia: organo ufficiale, Societa italiana di dermatologia e sifilografia1 53(2):208–215. https://doi.org/10.23736/s0392-0488.18.05922-9

Bussone G, Berezné A, Mouthon L (2009) Complications infectieuses de la sclérodermie systémique. La Presse Médicale 38(2):291–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lpm.2008.11.003

Allanore Y, Denton CP, Krieg T, Cornelisse P, Rosenberg D, Schwierin B, Matucci-Cerinic M (2016) Clinical characteristics and predictors of gangrene in patients with systemic sclerosis and digital ulcers in the digital ulcer outcome registry: a prospective, observational cohort. Ann Rheum Dis 75(9):1736–1740. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209481

Khanna D, Lin CJ, Furst DE, Goldin J, Kim G, Kuwana M, Allanore Y, Matucci-Cerinic M, Distler O, Shima Y, van Laar JM (2020) Tocilizumab in systemic sclerosis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med 8(10):963–974. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30318-0

Khanna D, Denton CP, Jahreis A, van Laar JM, Frech TM, Anderson ME, Baron M, Chung L, Fierlbeck G, Lakshminarayanan S, Allanore Y (2016) Safety and efficacy of subcutaneous tocilizumab in adults with systemic sclerosis (faSScinate): a phase 2, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 387(10038):2630–2640. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00232-4

Schlabs M, Pawlak-Buś K, Leszczyński P (2015) Retrospective analysis of infections prevalence in patients with progressive systemic sclerosis treated with cyclophosphamide. J Med Sci 84(3):152–156. https://doi.org/10.20883/medical.e12

Khanna D, Spino C, Johnson S, Chung L, Whitfield ML, Denton CP, Berrocal V, Franks J, Mehta B, Molitor J, Steen VD (2020) Abatacept in early diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis: results of a phase II investigator-initiated, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 72(1):125–136. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.41055

Mok CC, Kwok CL, Ho LY, Chan PT, Yip SF (2011) Life expectancy, standardized mortality ratios, and causes of death in six rheumatic diseases in Hong Kong. China Arthritis Rheum 63(5):1182–1189. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.30277

Elhai M, Meune C, Avouac J, Kahan A, Allanore Y (2012) Trends in mortality in patients with systemic sclerosis over 40 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Rheumatology 51(6):1017–1026. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ker269

Tyndall AJ, Bannert B, Vonk M, Airò P, Cozzi F, Carreira PE, Bancel DF, Allanore Y, Müller-Ladner U, Distler O, Iannone F (2010) Causes and risk factors for death in systemic sclerosis: a study from the EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research (EUSTAR) database. Ann Rheum Dis 69(10):1809–1815. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2009.114264

Netwijitpan S, Foocharoen C, Mahakkanukrauh A, Suwannaroj S, Nanagara R (2013) Indications for hospitalization and in-hospital mortality in Thai systemic sclerosis. Clin Rheumatol 32:361–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-012-2131-0

Sampaio-Barros PD, Bortoluzzo AB, Marangoni RG, Rocha LF, Del Rio AP, Samara AM, Yoshinari NH, Marques-Neto JF (2012) Survival, causes of death, and prognostic factors in systemic sclerosis: analysis of 947 Brazilian patients. J Rheumatol 39(10):1971–1978. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.111582

Steen VD, Medsger TA (2007) Changes in causes of death in systemic sclerosis, 1972–2002. Ann Rheum Dis 66(7):940–944. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2006.066068

Chung L, Krishnan E, Chakravarty EF (2007) Hospitalizations and mortality in systemic sclerosis: results from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Rheumatology 46(12):1808–1813. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kem273

Ram Poudel D, George M, Dhital R, Karmacharya P, Sandorfi N, Derk CT (2018) Mortality, length of stay and cost of hospitalization among patients with systemic sclerosis: results from the National Inpatient Sample. Rheumatology 57(9):1611–1622. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/key150

M AT (1980) Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Arthritis Rheum 13:577–580

Van Den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, Johnson SR, Baron M, Tyndall A, Matucci-Cerinic M, Naden RP, Medsger TA Jr, Carreira PE, Riemekasten G (2013) 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum 65(11):2737–2747. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.38098

Dixon WG, Symmons DP, Lunt M, Watson KD, Hyrich KL, Silman A (2007) Serious infection following anti–tumor necrosis factor α therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: lessons from interpreting data from observational studies. Arthritis Rheum 56(9):2896–2904. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.22808

Jang HJ, Woo A, Kim SY, Yong SH, Park Y, Chung K, Lee SH, Leem AY, Lee SH, Kim EY, Jung JY (2023) Characteristics and risk factors of mortality in patients with systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Ann Med 55(1):663–671. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2023.2179659

Tanaka M, Koike R, Sakai R, Saito K, Hirata S, Nagasawa H, Kameda H, Hara M, Kawaguchi Y, Tohma S, Takasaki Y (2015) Pulmonary infections following immunosuppressive treatments during hospitalization worsen the short-term vital prognosis for patients with connective tissue disease-associated interstitial pneumonia. Mod Rheumatol 25(4):609–614. https://doi.org/10.3109/14397595.2014.980384

Ou SM, Fan WC, Cho KT, Yeh CM, Su VY, Hung MH, Chang YS, Lee YJ, Chen YT, Chao PW, Yang WC (2014) Systemic sclerosis and the risk of tuberculosis. J Rheumatol 41(8):1662–1669. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.131125

Lu MC, Lai CL, Tsai CC, Koo M, Lai NS (2015) Increased risk of pulmonary and extra-pulmonary tuberculosis in patients with rheumatic diseases. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 19(12):1500–1506. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.15.0087

Hsu CY, Ko CH, Wang JL, Hsu TC, Lin CY (2019) Comparing the burdens of opportunistic infections among patients with systemic rheumatic diseases: a nationally representative cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther 21:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-019-1997-5

Ahmad QM, Shah IH, Nauman Q, Sameem F, Sultan J (2008) Increased incidence of tuberculosis in patients of systemic sclerosis on dexamethasone pulse therapy: a short communication from Kashmir. Indian J Dermatol 53(1):24–25

Global tuberculosis report. https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2022/tb-disease-burden/2-1-tb-incidence#:~:text=In%202021%2C%20eight%20countries%20accounted,Congo%20[2.9%25]%20

Mouthon L, Carpentier PH, Lok C, Clerson P, Gressin V, Hachulla E, Bérezné A, Diot E, Van Kien AK, Jego P, Agard C (2014) Ischemic digital ulcers affect hand disability and pain in systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol 41(7):1317–1323. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.130900

Yayla ME, Yurteri EU, Torğutalp M, Eroğlu DŞ, Sezer S, Dinçer AB, Gülöksüz EG, Yüksel ML, Yilmaz R, Ateş A, Turğay TM (2022) Causes of severe infections in patients with systemic sclerosis and associated factors. Turkish J Med Sci 52(6):1881–1888. https://doi.org/10.55730/1300-0144.5535

Braun-Moscovici Y, Keidar Z, Braun M, Markovits D, Toledano K, Tavor Y, Sabbah F, Rozin A, Dolnikov K, Balbir-Gurman A (2017) SAT0368 The prevalence of osteomyelitis in infected digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis patients. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-eular.6474

Giuggioli D, Manfredi A, Colaci M, Lumetti F, Ferri C (2013) Osteomyelitis complicating scleroderma digital ulcers. Clin Rheumatol 32:623–627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-012-2161-7

Giuggioli D, Manfredi A, Colaci M, Lumetti F, Ferri C (2012) Scleroderma digital ulcers complicated by infection with fecal pathogens. Arthritis Care Res 64(2):295–297. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20673

Klein NC, Go CH, Cunha BA (2001) Infections associated with steroid use. Infectious Dis Clin 15(2):423–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0891-5520(05)70154-9

Geirsson AJ, Akesson A, Gustafson T, Elner A, Wollheim FA (1989) Cineradiography identifies esophageal candidiasis in progressive systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 7(1):43–46

Hendel L, Svejgaard E, Walsøe I, Kieffer M, Stenderup A (2009) Esophageal candidosis in progressive systemic sclerosis: occurrence, significance, and treatment with fluconazole. Scand J Gastroenterol 23(10):1182–1186. https://doi.org/10.3109/00365528809090188

Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements PJ, Goldin J, Roth MD, Furst DE, Arriola E, Silver R, Strange C, Bolster M, Seibold JR (2006) Cyclophosphamide versus placebo in scleroderma lung disease. N Engl J Med 354(25):2655–2666. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa055120

Molloy ES, Calabrese CM, Calabrese LH (2017) The risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in the biologic era: prevention and management. Rheum Dis Clin 43(1):95–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdc.2016.09.009

Tashkin DP, Roth MD, Clements PJ, Furst DE, Khanna D, Kleerup EC, Goldin J, Arriola E, Volkmann ER, Kafaja S, Silver R (2016) Mycophenolate mofetil versus oral cyclophosphamide in scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease (SLS II): a randomised controlled, double-blind, parallel group trial. Lancet Respir Med 4(9):708–719. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30152-7

Zhang Guangfeng Xu, Ting ZH et al (2015) Randomized controlled study of mycophenolate mofetil and cyclophosphamide in the treatment of connective tissue disease-related interstitial lung disease. Chin Med J 95(45):3641–3645. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2015.45.001

Barnes H, Holland AE, Westall GP, Goh NS, Glaspole IN (2018) Cyclophosphamide for connective tissue disease–associated interstitial lung disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010908.pub2

Singh JA, Cleveland JD (2020) Serious infections in people with systemic sclerosis: a national US study. Arthritis Res Ther 22(1):163. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-020-02216-w

Komócsi A, Vorobcsuk A, Faludi R, Pintér T, Lenkey Z, Költő G, Czirják L (2012) The impact of cardiopulmonary manifestations on the mortality of SSc: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Rheumatology 51(6):1027–1036. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ker357

Elhai M, Meune C, Boubaya M, Avouac J, Hachulla E, Balbir-Gurman A, Riemekasten G, Airò P, Joven B, Vettori S, Cozzi F (2017) Mapping and predicting mortality from systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 76(11):1897–1905. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211448

Youssef J, Novosad SA, Winthrop KL (2016) Infection risk and safety of corticosteroid use. Rheum Dis Clin 42(1):157–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdc.2015.08.004

Acknowledgements

Authors thank Akshat Agarwal and Harshita Pandey for their voluntary contribution towards data entry, English language editing, and bibliography annotations in preparation of this manuscript

Funding

No funds were received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The conception and design of the study—AGP, LG, VA, SA; acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data—AGP, SSP, JRP, SA, VA. Drafting the article—AGP, SA, JRP, SSP, LG, AA, AL, DPM, AN, ZH, AK, RM, AR, NM, NJ; Revising it critically for important intellectual content—SA, VA, AGP, JRP, ZH, AN, LG. Final approval of the version to be submitted—All authors. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved—All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

None of the authors declare any conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Waiver of written informed consent for retrospective data retrieval was obtained from the Institute Ethics Committee, SGPGIMS, Lucknow, letter number PGI/BE/129/2020, date of approval 21-Feb-2020.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gollarahalli Patel, A., Ahmed, S., Parida, J.R. et al. Tuberculosis is the predominant infection in systemic sclerosis: thirty-year retrospective study of serious infections from a single centre. Rheumatol Int (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-024-05688-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-024-05688-0