Abstract

Giant cell arteritis (GCA), more common in Northern European populations, has limited data in Arabcountries. Our study reports GCA’s clinical manifestations in Jordan and reviews published research on GCA across Arab nations. In this retrospective analysis, GCA patients diagnosed from January 2007 to March 2019 at a Jordanian academic medical center were included through referrals for temporal artery biopsy (TAB). A comprehensive search in PubMed, Scopus, and the DOAJ (Directory of Open Access Journals) databases was conducted to identify all relevant English-language manuscripts from Arab countries on GCA without time limitations. Among 59 diagnosed GCA patients, 41 (69.5%) were clinically diagnosed with a negative TAB, and 19 (30.5%) had a positive result. Females comprised 74.6% (n = 44) with 1:3 male-female ratio. The mean age at diagnosis was 67.3 (± 9.5) years, with most presenting within two weeks (n = 40, 67.8%). Headache was reported by 54 patients (91.5%). Elevated ESR occurred in 51 patients (78%), with a mean of 81 ± 32.2 mm/hr. All received glucocorticoids for 13.1 ± 10 months. Azathioprine, Methotrexate, and Tocilizumab usage was 15.3% (n = 9), 8.5% (n = 5), and 3.4% (n = 2), respectively. Remission was observed in 57.6% (n=34), and 40.7% (n = 24) had a chronic clinical course on treatment. Males had higher biopsy-based diagnoses (p = .008), and biopsy-diagnosed patients were older (p = .043). The literature search yielded only 20 manuscripts originating in the Arab world. The predominant study types included case reports and retrospective analyses, with only one case series and onecase-control study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is a chronic inflammatory vasculitis involving the aorta and its major branches [1, 2]. GCA is believed to be most prevalent among older Europeans, particularly Northern Europeans (Scandinavians) [3, 4]. The diagnosis of GCA is based on the clinical presentation of a newly occurring temporal headache accompanied by symptoms like jaw claudication, visual disturbances, systemic features, evidence of large vessel involvement in vascular imaging, and/or histopathological findings indicating inflammation in the temporal artery [4]. Once diagnosed, typical treatment recommendations include oral/intravenous glucocorticoids and other medications such as methotrexate and tocilizumab [5, 6]. From an epidemiological standpoint, GCA has been the most extensively studied of all systemic vasculitides, but most data are derived from European studies [3, 7, 8]. Despite the well-documented geographic variation, which has the potential to influence disease classification and patient care, the EULAR and ACR guidelines rely heavily on this body of data as a foundation for their GCA management recommendations [5, 6, 9, 10]. Limited studies about GCA have been done in different countries in the Arab region, like Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, and Egypt [11,12,13,14,15]. This study aims to study the epidemiological, histopathological, and clinical features of GCA patients in Jordan for the first time and to comprehensively review all published research on GCA from the Arab world.

Methods

Study design and population

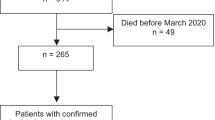

This retrospective study was conducted at the University of Jordan Hospital, the primary teaching hospital affiliated with the University of Jordan School of Medicine. Cases of GCA were recognized through the retrieval of all temporal artery biopsies (TAB) conducted between January 2007 and March 2019 from the pathology laboratory database. Our team had previously published details on TAB utilization for the diagnosis of GCA in a prior study [16]. Subsequently, patients’ files were meticulously reviewed to extract relevant data for this investigation, as outlined in the data collection section below. The study encompassed patients diagnosed with GCA The study encompassed patients diagnosed with GCA according to the American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of GCA, even in cases where biopsies yielded negative results.

Data collection

Information on demographics and clinical aspects, covering gender, age at the time of TAB, presenting symptoms, comorbidities, and medication details, were extracted from medical records. Additionally, the study documented laboratory findings, encompassing C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) levels, white blood cell count, hemoglobin, and serum albumin.

Ethical approval

The research protocol obtained approval from the Ethics Committee of the University of Jordan Hospital (IRB approval number: 67/2018/3476), and the study adhered to the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS version 22.0 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) software package. Descriptive statistics were used to present sample characteristics, including counts, percentages, means, and standard deviations. The association between outcomes and categorical independent variables was examined through the Chi-square test. At the same time, the t-test was employed to assess the relationship between outcomes and continuous independent variables. Following the validation of all statistical hypotheses, a binary logistic regression test was used to determine the outcome’s determinants. A p-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant.

Results

Sample characteristics

Fifty-nine patients diagnosed with GCA were cared for at the Jordan University Hospital (2008–2019). Forty-four patients were females (74.6%), while 15 patients were males (25.4%), yielding a male-female ratio of 1:3. The age at diagnosis ranged between 48 and 85 years, with a mean of 67.3 (± 9.5) years. Morbidities before the GCA diagnosis included 45 with hypertension (76.3%), 38 with diabetes (64.4%), 24 with ischemic heart disease (40.7%), and four with hypothyroidism (6.8%).

Patients were initially evaluated by rheumatologists in 24 (40.7% of cases), neurologists in 20 (33.9%), and ophthalmologists in 11 (18.6%), while other specialties first assessed the remaining four (6.8% of cases). Forty patients (67.8%) reported less than two weeks of symptoms at the time of the first presentation, seven patients (11.9%) reported six months of symptoms, and six (10.2%) reported symptoms for longer than a month.

The most frequently reported symptom was headache, which was reported by 54 patients (91.5%), followed by blurred vision in 23 (39%), PMR symptoms in 19 (32.2%), jaw claudication in 18 (30.5%), vision loss in 7 (11.9%), and temporal artery pulselessness and tenderness reported by seven patients (6.8%) (Table 1).

In 23 patients (39%), the ophthalmologic examination yielded normal findings, while in five patients (8.5%), it showed anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, and an additional five patients (8.5%) exhibited optic disc swelling. The status of the eye examination was unknown in the remaining 16 patients (27%) (Table 2). Among those with anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (n = 5), one (20%) reported vision loss, one (20%) reported blurred vision, one (20%) reported decreased visual activity, and two (40%) had no visual symptoms. Similarly, among those with optic disc swelling (n = 5), one (20%) reported vision loss, three (60%) reported blurred vision, and the remaining one patient (20%) had no visual symptoms.

Laboratory results

Regarding laboratory investigations (Table 2), 51 (78%) patients had elevated Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rates (ESR) ranging between 35 and 125 mm/hour (mean = 81 ± 32.2 mm/hour), 29 patients (49.2%) had elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), 23 patients (39%) had leukocytosis, 20 patients (33.9%) had anemia, five patients (8.5%) had elevated serum alkaline phosphatase, and four patients (6.8%) had low serum albumin.

Clinical management of the patients

Out of 59 patients, 45 (76.3%) were hospitalized at presentation, and all received glucocorticoids for a mean duration of 13.1 ± 10 months. Among them, 21 patients (35.6%) initially received glucocorticoids intravenously, followed by glucocorticoids Orally. Glucocorticoid-sparing immunosuppressant treatment included Azathioprine in nine (15.3%) of the patients and Methotrexate in five (8.5%), while Tocilizumab was utilized in only two patients (3.4%). Follow-up duration ranged from 1 to 123 months (mean = 23.6 ± 30.4 months). Remission was observed in 34 (57.6%) patients, while 24 (40.7%) patients had a chronic clinical course on treatment, and one (1.7%) patient experienced vision loss complications. Echo findings showed diastolic dysfunction in 27 (45.8%) patients, systolic dysfunction in two (3.4%), and none had an aortic aneurysm.

Biopsy proved GCA versus clinically based GCA

Out of the 59 patients, 41 (69.5%) received a clinical diagnosis of GCA despite a negative TAB, whereas only 18 (30.5%) were diagnosed with a positive TAB result. Two patients had delayed bleeding at the biopsy site, but the patients reported no other significant side effects. Comparisons between the two groups indicated that males have a significantly higher likelihood of being diagnosed through biopsy results than females (p = .008), and patients diagnosed based on biopsy results are significantly older (p = .043). However, the two groups did not differ in the length of symptoms before diagnosis, types of symptoms, laboratory results, or clinical outcome (Table 3).

Discussion

This study aimed to characterize Giant Cell Arteritis (GCA) within the Jordanian population. Over a span of 12 years, 59 patients were diagnosed with GCA through referrals for temporal artery biopsy (TAB). The likelihood of a significantly higher number of GCA cases is low, as our institution consistently refers all suspected cases to TAB, except in occasional instances where patients decline biopsy and choose clinical management.

Most patients in this study were females with a male-female ratio of 1:3, keeping with the general observation of female predominance in this disease [33,34,35]. Gender-based variations exist in immune responses, and women were shown to demonstrate greater susceptibility to drug effects than men [36]. The average age of patients at the time of diagnosis was 67 years, aligning with the literature, which indicates that GCA is less prevalent in individuals under 50 [5, 37]. Age-related remodeling of the immune system, both innate and adaptive, and age-related damage to the arterial wall may increase the risk of developing GCA [38]. However, the specific triggers and mechanisms of chronic damage in GCA remain unidentified [39]. The current pathogenic model is based on histopathological and immunopathological investigations showing arterial wall inflammation involving CD4 + T lymphocytes and macrophages, often organizing into granulomatous structures with the formation of giant cells [40]. There is a remarkable loss of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) and elastic fibers, which may potentially promote the development of aneurysms. Intimal hyperplasia and lumen blockage are caused by inflammation-induced vascular remodeling, which is the source of ischemic complications of the disease [40, 41].

Our institution utilizes a fast-track system of referring patients to specialists, with most patients having reported less than two weeks of symptoms at the time of the first presentation. It has been demonstrated that accelerated diagnostic and treatment procedures for GCA via Fast-track pathways, such as immediate referral to a specialist and the beginning of glucocorticoid therapy, can reduce the risk of GCA’s feared complications, such as vision loss [42]. New-onset headache is frequently encountered as a common presenting symptom of GCA and stands out among the most prevalent symptoms associated with GCA. In our patient cohort, headache was the most frequently reported symptom (91.5% of patients), followed by blurred vision, PMR, and jaw claudication—notably, none of the patients presented with limb claudication, peripheral ischemia, or stroke. In a study involving 240 Spanish patients with biopsy-confirmed GCA, 86.4% presented with headache, and in 33% of cases, it was the initial symptom [43].

Evidence of ocular complications was seen in a minority of the patients, as only five patients had anterior ischemic neuropathy, and the other five patients had optic disc swelling. In two studies done in Sweden, only 85 out of 840 GCA patients and 1618 out of 12,048 patients developed visual complications [44, 45]. Factors predicting ocular complications in these studies included male gender, hypertension, diabetes, absence of headache or abnormal temporal artery findings during clinical examination, use of β-adrenergic inhibitors, low C-reactive protein (CRP) levels at the time of diagnosis, and the lack of Polymyalgia Rheumatica (PMR) symptoms.

TAB is frequently recommended in all suspected cases of GCA as the gold standard for diagnosis [5], despite its limited sensitivity arising from the disease’s segmental nature and the patient’s presentation with a cranial or large-vessel phenotype [46]. Imaging and biopsy were shown to have comparable diagnostic values if the evaluators were competent with these techniques [6].

In our study, 70% of patients received clinical diagnoses of GCA despite negative TAB results. Notably, males were more frequently diagnosed based on biopsy results than females, and this subgroup exhibited a significantly older age. In a prospective, multicenter French study comprising 207 biopsy-proven and 85 negatively biopsied GCA patients, the biopsy-diagnosed group slightly included more females [47]. Furthermore, findings from a survey of 102 patients who underwent TAB Saudi Arabia indicated that patients diagnosed with biopsy results were significantly older, affirming the consistency with our study’s results [11].

No significant differences were observed between those diagnosed based on biopsy and those diagnosed based on clinical grounds regarding symptom duration, symptom types, laboratory results, or outcome. In the French study referenced above comparing these groups, the time from symptom onset to diagnosis was similar. Jaw claudication and temporal artery abnormalities were more frequent in the biopsy-positive group, while headache and PMR symptoms were notably more prevalent in the clinically diagnosed group. Sudden blindness occurred more frequently in the biopsy-positive group, while troubled vision showed a comparable occurrence in both groups [47]. Even though elevated inflammatory markers were found in over three-quarters of the patients in our study, high ESR was not correlated with positive TAB. In a study of 764 GCA patients, the estimated sensitivity of ESR for a positive TAB was 84.1%, emphasizing the need for cautious use and careful interpretation of inflammatory markers, especially concerning the timing of disease sampling [48].

In our study, all patients received glucocorticoids for a duration between 1 and 76 months. Twenty-one received parenteral (IV) glucocorticoids upon presentation, followed by oral glucocorticoids. Similarly, in the study in Saudi Arabia, all patients were treated with either intravenous or oral glucocorticoids before or after obtaining the results of TAB, and treatment lasted from 3 days to 6 years [11].

Initiation of high-dose oral glucocorticoids rather than moderate-dose glucocorticoids is recommended for all patients with GCA [5]. The appropriate dosage and method of glucocorticoid administration for newly diagnosed GCA depend on the presence of potential GCA-related visual symptoms, such as vision loss, or cerebrovascular events like stroke or transient ischemic attack. In such cases, a larger initial dose of glucocorticoids is required and should be promptly administered [5, 49]. The optimal duration for GCA glucocorticoid therapy is not defined and should be personalized. Additionally, glucocorticoid-sparing immunosuppressants like Tocilizumab or methotrexate are advised [6].

Only 16 patients in our study population utilized glucocorticoid-sparing agents, with 9 using Azathioprine, 5 using Methotrexate, and 2 using Tocilizumab. This limited usage may be attributed to many patients being diagnosed before the now widely accepted recommendations for administering glucocorticoid-sparing agents. Several studies highlight the effectiveness of immunosuppressants in GCA treatment. In a small study of 31 patients with GCA, PMR, or both, Azathioprine significantly reduced the mean prednisolone dose at 52 weeks [50]. As per Methotrexate, its adjunctive use with glucocorticoids led to a lower risk of relapses and reduced glucocorticoids exposure among 161 patients evaluated in randomized trials [51]. A year-long trial with 251 patients showed that achieving remission without glucocorticoids in GCA patients was superior to Tocilizumab compared to the placebo, and the drug has been approved as a treatment for GCA [5, 52]. Additionally, another study suggested that Mycophenolate might be considered a glucocorticoids -sparing agent, particularly for patients unresponsive to conventional therapy or those for whom glucocorticoids dosage reduction is strongly recommended [53].

We conducted a comprehensive search across PubMed, Scopus, and the Directory of Open Access databases to locate English-language manuscripts from Arab countries on Giant Cell Arteritis (GCA), with no restrictions on the timeframe. The search utilized keywords, including “Giant,” “Temporal arteritis,” and “Arab,” along with individual keywords for each Arab country (Algeria, Bahrain, Comoros, Djibouti, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen) (Table 4). Our search revealed only 20 studies conducted in the Arab world; 6 were in Saudi Arabia, five were in Lebanon, three were in Egypt, two were in Tunisia, and one was in Jordan, Morocco, Bahrain, UAE, and Kuwait. Of these, most were case reports and retrospective studies with only one case series and one case-control. The ages of the patients ranged from 60 to 80 years. Most of the patients in the retrospective studies presented with the well-known symptoms of GCA: headache, hardened and tender temporal arteries, jaw claudication, diplopia, and vision loss. Details of these studies can be found in Table 4.

The study’s results should be interpreted with awareness of certain limitations that might be addressed in future research. The study’s retrospective nature and the method of patient inclusion relied on reviewing referrals to TAB to determine whether patients could be diagnosed with GCA, potentially influencing the actual number of patients.

In conclusion, the Giant Cell Arteritis GCA diagnosis is uncommon in Jordan and rare among Arabs. The presenting symptoms and outcomes observed in this population are consistent with existing literature; however, there is a notable gap in research and awareness concerning GCA in this region. Therefore, further investigations and increased awareness are warranted to enhance our understanding of GCA’s prevalence, clinical manifestations, and management within the Jordanian and broader Arab populations.

Data availability

Data available upon reasonable request.

References

Castañeda S et al (Mar. 2022) Advances in the treatment of Giant Cell Arteritis. J Clin Med 11(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/JCM11061588

Jennette JC et al (2013) Jan., 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum 65(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/ART.37715

Watts, Scott (2014) Epidemiology of vasculitis. Case Stud Clin Psychol Science: Bridging Gap Sci Pract no August 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/MED/9780199659869.003.0002

Koster MJ, Matteson EL, Warrington KJ (2018) Large-vessel giant cell arteritis: diagnosis, monitoring and management. Rheumatology (Oxford) 57(suppl_2):ii32–ii42. https://doi.org/10.1093/RHEUMATOLOGY/KEX424

Maz M et al (2021) 2021 American College of Rheumatology/Vasculitis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Giant Cell Arteritis and Takayasu Arteritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 73(8):1349–1365. https://doi.org/10.1002/ART.41774

Hellmich B et al (Jan. 2020) 2018 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of large vessel vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis 79(1):19–130. https://doi.org/10.1136/ANNRHEUMDIS-2019-215672

Sonnenblick M, Nesher G, Friedlander Y, Rubinow A (1994) Giant cell arteritis in Jerusalem: a 12-year epidemiological study. Br J Rheumatol 33(10):938–941. https://doi.org/10.1093/RHEUMATOLOGY/33.10.938

Watts RA, Lane S, Scott DGI (2005) What is known about the epidemiology of the vasculitides? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 19(2):191–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BERH.2004.11.006

Kobayashi S, Fujimoto S (2013) Epidemiology of vasculitides: differences between Japan, Europe and North America. Clin Exp Nephrol 17(5):611. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10157-013-0813-9

Duhaut P, Bosshard S, Ducroix JP (2004) Is giant cell arteritis an infectious disease? Biological and epidemiological evidence. Presse Med 33(19 Pt 2):1403–1408. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0755-4982(04)98939-7

Chaudhry IA, Shamsi FA, Elzaridi E, Arat YO, Bosley TM, Riley FC (2007) Epidemiology of giant-cell arteritis in an arab population: a 22‐year study. Br J Ophthalmol 91(6):715. https://doi.org/10.1136/BJO.2006.108845

Khalifa M, Karmani M, Jaafoura NG, Kaabia N, Letaief AO, Bahri F (2009) Epidemiological and clinical features of giant cell arteritis in Tunisia. Eur J Intern Med 20(2):208–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EJIM.2008.07.030

The incidence of giant cell arteritis in Jerusalem over a 25-year period: annual and seasonal fluctuations - PubMed. Accessed: Aug. 10, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17428357/

Shahin AA et al (2018) The distribution and outcome of vasculitic syndromes among egyptians: a multi-centre study including 630 patients. Egypt Rheumatologist 40(4):243–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EJR.2018.01.001

Attia DHS, Abdel RA, Noor, Salah S (2019) Shedding light on vasculitis in Egypt: a multicenter retrospective cohort study of characteristics, management, and outcome. Clin Rheumatol 38(6):1675–1684. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10067-019-04441-4

Alnaimat F et al (2021) Clinical and technical determinants of positive temporal artery biopsy: a retrospective cohort study. Rheumatol Int 41(12):2157–2166. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00296-021-05028-6

Bosley TM, Riley FC (1998) Giant cell arteritis in Saudi Arabia. Int Ophthalmol 22(1):59–60. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006167213695/METRICS

Habib HM, Essa AA, Hassan AA (Feb. 2012) Color duplex ultrasonography of temporal arteries: role in diagnosis and follow-up of suspected cases of temporal arteritis. Clin Rheumatol 31(2):231–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10067-011-1808-0

Gruener AM, Chang JR, Bosley TM, Al-Sadah ZM, Kum C, McCulley TJ (2017) Relative frequencies of arteritic and nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy in an arab population. J Neuroophthalmol 37(4):382–385. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNO.0000000000000491

Mehta K et al (2022) The utility of the bilateral temporal artery biopsy for diagnosis of giant cell arteritis. J Vasc Surg 76(6):1704–1709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2022.04.043

Oumerzouk J, El Filali O, Zbitou A, Slioui B, Belasri S, Kissani N (2023) Neurological complications of giant cell arteritis: A study of 15 cases and a review of the literature. J Fr Ophtalmol 46(3):211–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JFO.2022.06.013

Al Tahan A, Al Rayess M, Abduljabbar M, Moallem MA (1997) Giant cell arteritis: report of two Saudi patients and review of the literature. Ann Saudi Med 17(2):237–239. https://doi.org/10.5144/0256-4947.1997.237

Achar KN, Al-alousi SS, Patrick JP (1994) Biliary ultrastructural changes in the liver in a case of giant cell arteritis. Br J Rheumatol 33(2):161–164. https://doi.org/10.1093/RHEUMATOLOGY/33.2.161

’Al-Alawi E, ’Al-Baharna I, ’Malik A, ’Al-Shoorqi E Giant cell arteritis: A typical case of ischaemic optic neuropathy due to GCA. International Journal of Medicine 5(2):106–108.

Haddad FG, El-Nemnoum R, Haddad F, Maalouly G, El-Rassi I (2008) Giant cell arteritis of the aorta: catastrophic complications without a preexisting aneurysm. Eur J Intern Med 19(7). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EJIM.2008.03.011

Haddad F, El-Rassi I, Haddad FG, Nemnoum R, Jebara VA (2008) Aorto-atrial fistula 10 days after dissection repair in giant cell arteritis. Ann Thorac Surg 86(5):1672–1674. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ATHORACSUR.2008.04.095

Mustafa KN, Hadidy A, Joudeh A, Obeidat FN, Abdulfattah KW (2015) Spinal cord infarction in giant cell arteritis associated with scalp necrosis. Rheumatol Int 35(2):377–381. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00296-014-3089-9

Wang SJ, Olson NJ, Kieffer KA (2016) A picture’s Worth: giant cell arteritis. Am J Med 129(9):942–944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.04.029

Albarrak AM, Mohammad Y, Hussain S, Husain S, Muayqil T (2018) Simultaneous bilateral posterior ischemic optic neuropathy secondary to giant cell arteritis: a case presentation and review of the literature. BMC Ophthalmol 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S12886-018-0994-9

Idoudi S et al (2020) Scalp Necrosis Revealing Severe Giant-Cell Arteritis. Case Rep Med 2020. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8130404

AlNuaimi D, Ansari H, Menon R, AlKetbi R, George A (2020) Large vessel vasculitis and the rising role of FDG PET-CT: a case report and review of literature. Radiol Case Rep 15(11):2246. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RADCR.2020.08.066

Mursi AM, Mirghani HO, Elbeialy AA (2022) A Case Report of Post COVID19 Giant Cell Arteritis and Polymyalgia Rheumatica With Visual Loss. Clin Med Insights Case Rep 15. https://doi.org/10.1177/11795476221088472

Dagostin MA, Pereira RMR, Dagostin MA, Pereira RMR (2020) Giant Cell Arteritis: Current Advances in Pathogenesis and Treatment. Vascular Biology - Selection of Mechanisms and Clinical Applications. https://doi.org/10.5772/INTECHOPEN.91018

Chean CS et al (2019) Characteristics of patients with giant cell arteritis who experience visual symptoms. Rheumatol Int 39(10):1789–1796. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00296-019-04422-5/TABLES/3

Gonzalez Chiappe S et al (2022) Incidence of giant cell arteritis in six districts of Paris, France (2015–2017). Rheumatol Int 42(10):1721–1728. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00296-022-05167-4/METRICS

Sakkas LI, Chikanza IC (2023) Sex bias in immune response: it is time to include the sex variable in studies of autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Rheumatol Int. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00296-023-05446-8

Ince B et al (2021) Long-term follow-up of 89 patients with giant cell arteritis: a retrospective observational study on disease characteristics, flares and organ damage. Rheumatol Int 41(2):439–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00296-020-04730-1/METRICS

Mohan SV, Liao YJ, Kim JW, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM (2011) Giant cell arteritis: immune and vascular aging as disease risk factors. Arthritis Res Ther 13(4):231. https://doi.org/10.1186/AR3358

Ciccia F, Macaluso F, Mauro D, Nicoletti GF, Croci S, Salvarani C (2021) New insights into the pathogenesis of giant cell arteritis: are they relevant for precision medicine? Lancet Rheumatol 3(12):e874–e885. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2665-9913(21)00253-8

Immunohistochemical analysis of lymphoid and macrophage cell subsets and their immunologic activation markers in temporal arteritis. Influence of corticosteroid treatment - PubMed. Accessed: Aug. 10, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2787641/

Dejaco C, Brouwer E, Mason JC, Buttgereit F, Matteson EL, Dasgupta B (2017) Giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica: current challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Rheumatol 13(10):578–592. https://doi.org/10.1038/NRRHEUM.2017.142

Fast track pathway reduces sight loss in giant cell arteritis: results of a longitudinal observational cohort study - PubMed. Accessed: Aug. 10, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26016758/

Gonzalez-Gay MA, Barros S, Lopez-Diaz MJ, Garcia-Porrua C, Sanchez-Andrade A, Llorca J (2005) Giant cell arteritis: disease patterns of clinical presentation in a series of 240 patients. Medicine 84(5):269–276. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MD.0000180042.42156.D1

Saleh M, Turesson C, Englund M, Merkel PA, Mohammad AJ (2016) Visual complications in patients with biopsy-proven giant cell arteritis: a Population-based study. J Rheumatol 43(8):1559. https://doi.org/10.3899/JRHEUM.151033

Ji J, Dimitrijevic I, Sundquist J, Sundquist K, Zöller B (2017) Risk of ocular manifestations in patients with giant cell arteritis: a nationwide study in Sweden. Scand J Rheumatol 46(6):484–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/03009742.2016.1266030

Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ (2003) Giant-Cell Arteritis and Polymyalgia Rheumatica. Ann Intern Med 139(6). https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-139-6-200309160-00015

Duhaut P et al (1999) Biopsy proven and biopsy negative temporal arteritis: differences in clinical spectrum at the onset of the disease. Ann Rheum Dis 58(6):335. https://doi.org/10.1136/ARD.58.6.335

Kermani TA et al (2012) Utility of erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein for the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 41(6):866–871. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SEMARTHRIT.2011.10.005

Kokloni IN, Aligianni SI, Makri O, Daoussis D (2022) Vision loss in giant cell arteritis: case-based review. Rheumatol Int 42(10):1855–1862. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00296-022-05160-X/METRICS

De Silva M, Hazleman BL (1986) Azathioprine in giant cell arteritis/polymyalgia rheumatica: a double-blind study. Ann Rheum Dis 45(2):136–138. https://doi.org/10.1136/ARD.45.2.136

Mahr AD et al (2007) Adjunctive methotrexate for treatment of giant cell arteritis: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum 56(8):2789–2797. https://doi.org/10.1002/ART.22754

Stone JH et al (2017) Trial of Tocilizumab in Giant-Cell Arteritis. New England Journal of Medicine 377(4):317–328. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMOA1613849/SUPPL_FILE/NEJMOA1613849_DISCLOSURES.PDF

Sciascia S et al (2012) Mycophenolate mofetil as steroid-sparing treatment for elderly patients with giant cell arteritis: report of three cases. Aging Clin Exp Res 24(3):273–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03325257

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All co-authors take full responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

all authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

not applicable.

Disclaimer

No part of this manuscript is copied or published elsewhere in whole or in part in any language.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Alnaimat, F., Alduradi, H., Al-Qasem, S. et al. Giant cell arteritis: insights from a monocentric retrospective cohort study. Rheumatol Int 44, 1013–1023 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-024-05540-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-024-05540-5