Abstract

Anti-U1-RNP antibodies are necessary for the diagnosis of mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD), but they are also prevalent in other connective tissue diseases, especially systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), from which distinction remains challenging. We aimed to describe the presentation and outcome of patients with anti-U1-RNP antibodies and to identify factors to distinguish MCTD from SLE. We retrospectively applied the criteria sets for MCTD, SLE, systemic sclerosis (SSc) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) to all patients displaying anti-U1-RNP antibodies in the hospital of Caen from 2000 to 2020. Thirty-six patients were included in the analysis. Eighteen patients (50%) satisfied at least one of the MCTD classifications, 11 of whom (61%) also met 2019 ACR/EULAR criteria for SLE. Twelve other patients only met SLE without MCTD criteria, and a total of 23 patients (64%) met SLE criteria. The most frequent manifestations included Raynaud’s phenomenon (RP, 91%) and arthralgia (67%). We compared the characteristics of patients meeting only the MCTD (n = 7), SLE (n = 12), or both (n = 11) criteria. Patients meeting the MCTD criteria were more likely to display SSc features, including sclerodactyly (p < 0.01), swollen hands (p < 0.01), RP (p = 0.04) and esophageal reflux (p < 0.01). The presence of scleroderma features (swollen hands, sclerodactyly, gastro-oesophageal reflux), was significantly associated with the diagnosis of MCTD. Conversely, the absence of those manifestations suggested the diagnosis of another definite connective tissue disease, especially SLE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) is an autoimmune disease first described in 1972 by Sharp et al. [1]. It is a clinical and biological entity defined as a connective tissue disease (CTD) with overlapping features of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), polymyositis/dermatopolymyositis (PM/DM) and/or systemic sclerosis (SSc), and it is biologically associated with autoantibodies directed against the U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein autoantigen (U1-snRNP or U1-RNP) [2]. U1-RNP antibodies are required for diagnosis, but they are also found in 13% of SLE [3, 4], 5–10% of SSc [5] and healthy controls [6].

Diagnosis of MCTD is challenging given the overlapping symptoms found in different connective tissue diseases. The heterogeneity of disease presentations explains why three different classifications, all dating from 1987, have been proposed for the diagnosis of MCTD. [1, 7, 8] The classifications from Sharp, Alarçon-Segovia and Kasukawa have been applied in different studies and have helped diagnose MCTD with sensitivities of 42%, 73% and 75%, respectively [9, 10]. However, some retrospective studies showed that up to 70% of patients diagnosed with MCTD at onset experienced an evolution of the MCTD into a distinct connective tissue disease over a follow-up period of 10 years [11,12,13,14,15]. It was thus proposed that MCTD could be a kind of undifferentiated CTD (UCTD) [11, 16, 17]; this concept is supported by studies showing that the clinical presentation of MCTD at diagnosis and after a 5-year follow-up was comparable with that of UCTD [18]. Additionally, in studies dealing with MCTD, some patients satisfying the MCTD classification criteria also meet the criteria for another connective tissue disease, SLE in most cases [16, 18,19,20,21].

snRNP is a nuclear RNA complex of U1-snRNP, comprising U1-A, U1-C and U1-70 K subunits, bound to 5 Sm proteins. Typically, MCTD is associated with autoantibodies directed against the U1-A, U1-C and U1-70 K proteins of snRNP, whereas SLE is associated with autoantibodies directed against Sm proteins, to which they are highly specific [22]. However, the distinction between the two can remain challenging, as cross-reactivity between the two can occur [23], and some immunoblotting techniques detect antibodies directed against the Sm/RNP complex without distinction. In addition, approximately 20% of patients diagnosed with MCTD display anti-dsDNA autoantibodies and anti-Sm autoantibodies [9, 24], which emphasizes the challenge of distinguishing MCTD from SLE. Finally, the existence of MCTD as a distinct connective tissue disease remains controversial, and the clinical relevance of anti-U1-RNP positivity is unclear [21, 25,26,27]. Although CTDs belong to the same family of autoimmune rheumatic diseases, both their management and prognosis drastically differ. Therefore, improving our knowledge about the different presentations appears crucial to properly classifying patients [28,29,30].

In this monocentric study, we aimed to deeply analyze the clinical presentation and outcomes of patients positive for U1-RNP antibodies. Based on their clinical presentations, we analyzed whether the three aforementioned classification criteria for MCTD or the criteria for SLE, SSc and RA could be applied to each patient. According to the different disease patterns we observed, we aimed to identify factors at baseline and during follow-up that helped to better distinguish MCTD from SLE.

Patients and methods

Study population and data collection

The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Caen Normandie and of the Caen University Hospital Center (Approval No. 2020–1489).

Until 2019, the immunodots used in the department of Immunology at the Caen University Hospital only detected anti-Sm/RNP without distinction between anti-U1-RNP and anti-Sm antibodies. In 2020, detection of anti-U1-RNP became available.

This monocentric retrospective study included all consecutive patients with positive anti-Sm/RNP antibodies screened in the Department of Immunology of our hospital between 2000 and 2020, and each serum sample was then tested for the presence of anti-U1-RNP antibodies (Scleroderma Profile 10 IgG DOT, Eurobio Scientific). All patients with positive anti-U1-RNP antibodies were included in the analysis. Ten consecutive patients with positive anti-Sm/RNP antibodies but negative anti-U1-RNP antibodies who fulfilled the 2019 ACR/EULAR criteria for SLE [31] were included as the control group for SLE.

Medical records were reviewed retrospectively, and patient data, including clinical, biological and radiological information, treatments and outcomes, were collected by a single investigator (IE).

Data were extracted from the first medical reports. Briefly, in each patient, we retrieved demographics and clinical data at onset, including skin symptoms (rash, Raynaud’s phenomenon, photosensitivity, alopecia, swollen hands, sclerodactyly, joint symptoms (arthralgia, arthritis), digestive symptoms, (gastroesophageal reflux, transit disorder), dyspnea, myalgia, neurological symptoms (central nervous system involvement, peripheral neuropathy, psychiatric disorders), thoracic pain and mucosal dryness.

Laboratory tests included blood count, hemoglobin, red and white blood cell and platelet counts, urinalysis, 24-h urine protein excretion, serum creatinine, C-reactive protein (CRP), creatine kinase protein (CK), and liver enzymes. Anti-nuclear antibodies (ANAs) were detected on Hep-2 cells by indirect immunofluorescence. The ANA assay (ImmuGlo™ ANA HEp-2 Substrate, Immco) was considered positive when serum titers were above 1:160 [32]. Serum concentrations of autoantibodies were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for anti-RNP/Sm, anti-Sm, anti-SSA/Ro, anti-SSB/La (ENAcombi, Orgentec), antidsDNA (Anti-DNA Antibody, double-stranded, Sigma), anti-CCP (AESKULISA CCP IgG, Eurobio Scientific) and rheumatoid factor (RF, in-house ELISA adapted from [33]). IgG anti-U1-RNP antibodies were detected using the Scleroderma Profile 10 IgG DOT (Eurobio Scientific), and a result > 5 UA was considered positive, as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Antiphospholipid antibodies (anti-cardiolipin, lupus anticoagulant and Anti-β2- glycoprotein (anti-B2GPI)) were analyzed by ELISA (Cardiolipin from Sigma and B2GPI from Eurodiagnostica), and were considered positive if they tested positive twice in a 12-week period [34]. Anti-β2-GPI was considered positive if IgG was > 5 UA/mL or IgM was > 10UA/mL. Anticardiolipin was considered positive if IgG was > 4 UGPL or IgM was > 4 UMPL according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Lupus anticoagulant (LAC) was analyzed both by dilute Russel viper venom time (dRVVT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and was considered positive if either one was positive.

Complement exploration included the detection of C3 and C4 by nephelometry, and total hemolytic complement (CH50) was assessed by lytic assay.

Other immunologic tests retrieved included Coombs test, serum protein electrophoresis and detection of cryoglobulinemia.

When available at diagnosis and during follow-up, we retrieved echocardiography, chest computed tomography, capillaroscopy, pulmonary function testing, and histology (e.g., renal or salivary gland biopsy) results for each patient. Treatments and outcomes were also collected. Finally, we noted the final diagnosis retained by the physician in charge of the patient.

In case of missing data (exam not performed or not reported in medical records), statistical analyses only considered available data.

Classifications and definitions

In each patient, we applied the three classification criteria sets for MCTD [1, 7, 8], and ACR/EULAR criteria for SLE, SSc, RA, and Sjögren syndrome [35,36,37,38,39]. Patients could satisfy multiple criteria sets. Patients were classified with MCTD if they satisfied at least one of the three criteria set for MCTD.

We divided the included patients into four groups:

-

“MCTD without SLE criteria”: patients fulfilling at least one MCTD criteria set but not the SLE criteria set

-

“SLE without MCTD criteria”: patients meeting the SLE criteria but none of the MCTD criteria sets

-

“MCTD and SLE criteria”: patients meeting the SLE criteria and at least one MCTD criteria set.

-

“Unclassified”: patients fulfilling none of the CTD classification criteria sets.

We collected data from echocardiography and high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) for the detection of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) and interstitial lung disease (ILD) when available, either at diagnosis or during follow-up.

PAH was definitive when mean pulmonary arterial pressure was ≥ 2 mmHg measured with right heart catheterization and suspected when pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) using tricuspid valve velocity was approximately ≥ 40 mmHg on echocardiography. [40]

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) was assessed by HRCT showing ground-glass opacities, reticulations, traction bronchiectasis, bronchiolestasis or honeycombing and/or pulmonary function test (PFT) displaying restrictive ventilator defect defined by total lung capacity (TLC) < 80% or diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon dioxide (DLCO) < 80% [41].

Worsening of ILD was defined by an increase in radiological anomalies assessed by a trained radiologist or deterioration of restrictive ventilator defect or DLCO measured with PFT.

Myositis was defined by myalgia with high titers of CK associated with muscle inflammation assessed by muscle biopsy and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [42].

Pericarditis was defined by the association of thoracic pain, elevated troponin and pericardial effusion in echocardiography [43].

Mucosal dryness was explored with labial salivary gland biopsy and classified using the Chisholm and Mason grading system [44].

The histology of renal biopsies was analyzed using the International Society of Nephrology for Lupus nephritis [38].

Statistical analysis

The categorical variables were analyzed by using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact probability test as appropriate. Continuous variables in two or three groups were compared using the Mann–Whitney test or the Kruskal–Wallis test, respectively.”

The statistical analyses were computed using JMP 9.0.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A p ≤ 0.05 defined statistical significance.

Results

Ninety-nine patients with anti-Sm/RNP antibodies were identified between 2000 and 2020, of which thirty-six were positive for anti-U1-RNP antibodies (36%).

Classification (Table 1)

Eighteen patients (50%) satisfied at least one of the MCTD criteria classifications, 11 of whom (61%) also met the ACR/EULAR criteria for SLE. Twelve other patients only met SLE criteria without MCTD criteria, and a total of 23 patients (64%) met SLE criteria. Six patients remained unclassified (17%). Only two of the 36 patients included (6%) solely met the MCTD criteria, and 16 of the 18 patients (89%) who fulfilled the MCTD criteria additionally meet the criteria for another CTD.

Seven patients fulfilled at least one of the MCTD criteria sets but not the SLE criteria sets and constituted the group “MCTD without SLE”. Twelve patients fulfilled SLE criteria but none of the MCTD criteria sets and were included in the group “SLE without MCTD”. Eleven patients met both SLE and MCTD criteria and constituted the group “MCTD and SLE criteria”. While 5/7 patients (71%) with MCTD without SLE and 8/12 patients (67%) with SLE without MCTD were diagnosed as such by physicians, the 11 patients with MCTD and SLE criteria received heterogeneous diagnoses: MCTD (n = 6, 50%), SLE (n = 2, 17%), overlap syndrome, SSc and UCTD (n = 1 each, 8%).

Baseline characteristics (Table 2)

Clinical data at diagnosis were available for all 36 patients. Thirty-one patients were women (86%), and the median age at diagnosis of the CTD was 32 [14–67] years. Tobacco use was reported in 11 patients (31%). The most common manifestations included Raynaud’s phenomenon (29 patients, 91%) and arthralgia (24 patients, 67%). Scleroderma-like manifestations such as telangiectases, swollen hands, sclerodactyly, digital ulcers and esophageal reflux were reported in 17–28% of patients, while SLE manifestations including alopecia, malar rash and lymphadenopathy were reported in 17–31%. Sjögren syndrome features were reported in 13 patients (36%), 9 of whom (70%) displayed focal lymphocytic sialadenitis. A scleroderma pattern was observed in 10 out of the 19 patients (53%) who underwent nailfold capillaroscopy, including 6 who also displayed scleroderma manifestations and 1 who exhibited isolated Raynaud’s phenomenon, and consisted of giant capillaries (n = 5), hemorrhages (n = 4) and capillary losses (n = 2).

Hypergammaglobulinemia was observed in 20 patients (56%) with a median of 20,3 [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46] g/L. Hypocomplementemia was reported in 17/33 patients (52%) and consisted of low C3 in 14 patients and low C4 in 11.

The most frequently used treatments were hydroxychloroquine and glucocorticoids in 26 (72%) and 27 (75%) patients, respectively. The use of immunosuppressant drugs was necessary in 19 (53%) patients, 10 of whom (53%) required more than 1 immunosuppressant. Immunosuppressant therapy was prescribed for organ involvement in nine patients (47%) and skin/joint manifestations in 10 (53%). The most commonly used immunosuppressants were mycophenolate mofetil (n = 10) and methotrexate (n = 9). Cyclophosphamide was used in five patients, four of whom displayed lupus nephritis and one who had anti-phospholipid syndrome with acute ischemic stroke.

Distinction between SLE and MCTD in patients with anti-U1-RNP antibodies (Table 3)

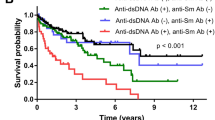

We compared the characteristics of patients meeting both MCTD and SLE criteria (n = 11), isolated SLE (SLE without MCTD criteria, n = 12) and isolated MCTD (MCTD without SLE criteria, n = 7) (Table 3). Unclassified patients were not included in this analysis (n = 6) and each patient was only included once in the appropriate diagnosis group (n = 30). The demographics did not differ between groups. MCTD without SLE criteria patients were more likely to display scleroderma-like symptoms than patients meeting the SLE criteria, although 50% of them did not meet the SSc criteria. RP was twice as frequent in patients with MCTD without SLE criteria (7/7 vs 6/12, p = 0.04) and swollen hands were four times more frequent than in patients with MCTD and SLE criteria (5/7 vs 0/12, p < 0.01). Sclerodactyly and gastroesophageal reflux occurred in 57–71% of MCTD patients but in only 45–27% of patients meeting MCTD and SLE criteria and never in SLE without MCTD patients (p < 0.01). Biologically, hypocomplementemia was a hallmark of patients meeting SLE criteria, which was displayed by 8/9 patients (89%) meeting MCTD and SLE criteria and 7 patients (59%) meeting SLE but not MCTD criteria versus 0 patients meeting MCTD but not SLE criteria (p < 0.01). However, SLE features such as alopecia, malar rash and anti-Sm positivity did not differ between groups. Anti-dsDNA positivity was significantly more frequent in patients meeting the SLE criteria (67% vs 0%, p = 0.01). Lupus nephritis always occurred in patients meeting SLE without MCTD and MCTD with SLE criteria; it occurred in six patients of the SLE without MCTD criteria group and in two of the MCTD and SLE criteria group, and was responsible for renal failure in two patients of the without MCTD criteria group. Mucosal dryness was more frequent in patients meeting the MCTD and SLE criteria (64% versus 8–43% in the two other groups, p = 0.02), and 57% of them fulfilled the ACR/EULAR criteria for Sjögren syndrome. Anti-SSA antibodies were present in 17 of these patients (64%).

Regarding therapeutics, methylprednisolone pulses were used in seven patients in the group SLE without MCTD criteria; for lupus nephritis in five patients and for the anti-phospholipid syndrome (APS) with ischemic stroke and digital ulcers in one patient. There was no difference in glucocorticoid, hydroxychloroquine, or immunosuppressant use among the three groups. The outcome was overall favorable in the three groups with no death after a mean follow-up of 6 years. Complications at follow-up did not statistically differ between groups and included pericarditis (n = 4), immune cytopenias (n = 3), scleroderma renal crisis (n = 1), myositis (n = 1), and PAH (n = 1). There was no increase in ILD in the affected patients in any group. Deterioration of pulmonary function testing occurred in one patient in the SLE without MCTD criteria and MCTD and SLE criteria groups (mean decrease in DLCO of 28 mmHg). Radiological ILD did not increase, and no specific treatment was undertaken.

Distinction between SLE patients with and without anti-U1-RNP antibodies (Table 4)

We compared the characteristics of the 11 patients with anti-U1-RNP antibodies belonging to the SLE without MCTD criteria group with the ten patients with SLE with anti-Sm/RNP but without anti-U1-RNP antibodies. Overall, there was no difference between the two groups. Raynaud’s phenomenon was the most frequent symptoms in both groups (six patients in each group, 50–60%).

Scleroderma-like features, including swollen hands, telangiectases, sclerodactyly and gastroesophageal reflux, were rare and occurred in 0–30% of patients in both groups, while SLE features, such as malar rash, alopecia, lymphadenopathy, hypocomplementemia and anti-Sm/anti-dsDNA positivity, were displayed in 20–70% of patients. ILD occurred in one patient with anti-U1-RNP antibodies and in two without. There was no difference in the prevalence of scleroderma-like or SLE features between the two groups.

Unclassified patients

Six patients met none of the criteria sets for CTDs. The most frequently reported features were Raynaud’s phenomenon (100%), arthralgias (three patients, 50%), transit disorders (three patients, 50%), lymphopenia and hypergammaglobulinemia (four patients, 67%).

The diagnoses made by physicians were autoimmune hepatitis, paraneoplastic lupus, ankylosing spondylitis in one patient each and MCTD in three patients. The outcome was favorable in all patients but one who died of complications of pre-existing colorectal cancer. All remained with an unclassified disease at the end of the follow-up.

Discussion

Here, we describe a series of 36 patients with anti-U1-RNP antibodies in a monocentric university hospital study. We show that while anti-U1-RNP positivity is classically associated with MCTD, the vast majority of our patients met the criteria for another definitive CTD, most often SLE. We found that patients with anti-U1-RNP antibodies have a common presentation of Raynaud’s phenomenon and arthralgia and/or synovitis. Patients meeting SLE criteria displayed features and complications associated with SLE, while patients only meeting MCTD criteria exhibited an SSc-like pattern, namely, Raynaud’s phenomenon, sclerodactyly, and gastroesophageal reflux. We also found that the swollen hand pattern was more specifically associated with MCTD without SLE.

None of the two patients fulfilling only the MCTD criteria experienced the evolution of the MCTD into another definitive CTD during follow-up. A quarter of patients had organ involvement requiring immunosuppressants, without distinction between groups, which confirms the potential for an aggressive course in anti-U1-RNP-associated CTD previously described [9, 45, 46].

Though they share many clinical features, the existence of specific life-threatening manifestations has made it imperative to distinguish SLE from MCTD. While SLE and MCTD display common immune pathways, such as interferon-gamma involvement and IL-2/IL-4 production, it was suggested that differences in immune activation of TLR3 in MCTD and TLR7 in SLE could account for the differences in clinical presentation between the two diseases, particularly the higher prevalence of lung involvement in MCTD [2, 19]. Our results are in accordance with previous works. Patients who satisfied MCTD criteria seemed more likely to develop lung involvement than patients without MCTD but with SLE criteria. This finding is concordant with the rarity of anti-dsDNA-positive patients in a published series of MCTD patients with ILD [47]. Conversely, nephritis only occurred in patients who satisfied at least SLE criteria but in no patient with isolated MCTD. This distinction of nosologic patterns at diagnosis and during follow-up thus appears relevant as it can guide the monitoring of patients during the follow-up. Accordingly, the monitoring of patients with anti-U1-RNP antibodies and SLE criteria should probably be the same as for other patients with SLE, including a regular measurement of proteinuria, and excluding the annual repetition of cardiac echography and HRCT in asymptomatic patients [31, 48]. Conversely, our data suggest that patients with MCTD without SLE criteria may more likely suffer from lung and gastrointestinal involvement. Although pulmonary complications in isolated MCTD, including ILD and PAH, were rare in our series, other studies described higher rates up to 65% PAH [49, 50] and 53% ILD [10, 50].

Validated recommendations for the assessment and management of MCTD are required. Some studies recommended not systematically screening asymptomatic patients with MCTD for ILD [30]. However, the occurrence of shortness of breath in these patients should be closely monitored because of the high frequency of pulmonary complications. Carpintero et al. reported a series of 79 patients with anti-U1RNP antibodies, among whom 47% met both the Alarcon-Segovia and SLICC criteria and displayed mixed clinical features but had less renal involvement and increased lung disease [51]. In our series, while 72% of patients meeting MCTD criteria met ≥ 2 criteria sets, 45% of patients meeting both MCTD and SLE criteria sets met only one classification set, and none met the three sets, which reflects the ambiguity of these cases and advocates for the need for tools to better classify these patients. Mesa et al. [52] developed a novel classification rule, “Lu-vs-M”, to distinguish SLE from MCTD in unclear cases with an overall accuracy of 88%. They identified several discriminating items, some of which were described in our analyses, such as anti-dsDNA antibody positivity, hypocomplementemia and skin sclerosis, as well as other items that were not significant in our series, including calcinosis, thrombopenia and CPK elevation. In accordance with previous studies, the reactivity for U1-RNP peptides was associated with IgG-based reactivity in MCTD patients versus IgM-based reactivity in SLE patients [4, 45, 52, 53]; while the authors found that anti-IgM reactivity for anti-U1-RNP seemed helpful in unclear cases for the diagnosis of SLE, its routine use is not warranted, as its detection requires specific blot dots.

The question of whether patients with SLE criteria and anti-U1-RNP antibodies should be considered as SLE or unclassified CTD still remains unresolved. We observed no differences in the presentation or outcomes of SLE patients with and without anti-U1-RNP antibodies. Our study thus may suggest that anti-U1-RNP antibodies might be included in the immunological patterns of SLE, as are anti-Sm or anti-dsDNA antibodies. However, other studies have suggested a higher frequency of scleroderma-like features in SLE patients harboring anti-RNP antibodies, including sclerodactyly and ILD, along with more severe nail fold capillaroscopy [4, 54]. Conversely, research has reported that lupus nephritis may occur less frequently in SLE patients with anti-RNP antibodies [4] which was not supported in our series. These discrepancies might be explained by our low number of patients in each group. The strength of our study is the inclusion of all patients with anti-U1-RNP antibody positivity in our center over the last two decades. Moreover, our monocentric study provides a glimpse of the real-life experience of a cohort of anti-U1-RNP-positive patients, as attested by the low frequency of life-threatening complications displayed. However, this study has several limitations, especially its retrospective nature resulting in missing data. In addition, the retrospective testing of anti-U1-RNP antibodies could have led to the exclusion of patients whose serum was unavailable. Since patients were evaluated by different physicians during follow-up, some information biases might exist regarding the notification of symptoms. However, all physicians in our department are experimented with the evaluation and care of patients with CTD. Future studies should include standardized data collection to minimize this bias.

The small sample size limits the interpretation and external validity of our observations precluding any definite conclusions. Our observations require replication in larger prospective studies. Although we performed statistical analyses, some of them found significant differences, we believe the main interest of our study is to provide a real-life picture of clinical and biological phenotypes of patients with anti-U1-RNP antibodies. In addition, we aimed to highlight the difficulty classifying patients using the different currently available classifications.

Finally, worsening ILD was based on the opinions of the radiologists and pneumologists in charge of the patients. Some discrepancies may thus exist among patients regarding the cut-off values above which ILD was considered worsening.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the need for validated tools to classify patients with anti-U1-RNP antibodies remains critical, and the available criteria sets appear unfit for a subset of unclear cases. Our study, however, showed that some patients with positive anti-U1-RNP antibodies displayed features suggestive of isolated MCTD, which appears as a distinct condition. Other patients showed a true overlap with SLE, which may be considered a pattern of this disease. This observational study requires further larger studies to improve the classification of these patients, especially as some of them remain unclassified.

Open data sharing statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

References

Sharp GC, Irvin WS, Tan EM, Gould RG, Holman HR (1972) Mixed connective tissue disease-an apparently distinct rheumatic disease syndrome associated with a specific antibody to an extractable nuclear antigen (ENA). Am J Med 52:148–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(72)90064-2

Greidinger EL, Hoffman RW (2005) Autoantibodies in the pathogenesis of mixed connective tissue disease. Rheum Dis Clin N Am 31:437–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdc.2005.04.004

Cervera R, Khamashta MA, Hughes GRV (2009) The Euro-lupus project: epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus in Europe. Lupus 18:869–874. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203309106831

Dima A, Jurcut C, Baicus C (2018) The impact of anti-U1-RNP positivity: systemic lupus erythematosus versus mixed connective tissue disease. Rheumatol Int 38:1169–1178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-018-4059-4

Abbara S, Seror R, Henry J, Chretien P, Gleizes A, Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Mariette X, Nocturne G (2019) Anti-RNP positivity in primary Sjögren’s syndrome is associated with a more active disease and a more frequent muscular and pulmonary involvement. RMD Open 5:e001033. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2019-001033

Li X, Liu X, Cui J, Song W, Liang Y, Hu Y, Guo Y (2019) Epidemiological survey of antinuclear antibodies in healthy population and analysis of clinical characteristics of positive population. J Clin Lab Anal 33:e22965. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.22965

Alarcón-Segovia VMD (1987) Classification and diagnostic criteria for mixed connective tissue disease. pp 33–40

Kasukawa TTR (1987) Preliminary diagnostic criteria for classification of mixed connective tissue disease. Mix connect tissue dis anti-nucl antibodies. Elsevier Science Publishers B.V (Biomedical Division), Amsterdam, pp 41–47

Cappelli S, Randone SB, Martinovic D, Tamas MM, Pasalic K, Allanore Y, Mosca M, Talarico R, Opris D, Kiss CG, Tausche AK, Cardarelli S, Riccieri V, Koneva O, Cuomo G, Becker MO, Sulli A, Guiducci S, Radic M, Bombardieri S, Aringer M, Cozzi F, Valesini G, Ananyeva L, Valentini G, Riemekasten G, Cutolo M, Ionescu R, Czirják L, Damjanov N, Rednic S, Cerinic MM (2012) “To be or not to be”, ten years after evidence for mixed connective tissue disease as a distinct entity. Semin Arthritis Rheum. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.07.010

John KJ, Sadiq M, George T, Gunasekaran K, Francis N, Rajadurai E, Sudarsanam TD (2020) Clinical and immunological profile of mixed connective tissue disease and a comparison of four diagnostic criteria. Int J Rheumatol 2020:9692030. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/9692030

Gendi NS, Welsh KI, Van Venrooij WJ, Vancheeswaran R, Gilroy J, Black CM (1995) HLA type as a predictor of mixed connective tissue disease differentiation. Ten-year clinical and immunogenetic followup of 46 patients. Arthritis Rheum 38:259–266. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.1780380216

De Clerck LS, Meijers KA, Cats A (1989) Is MCTD a distinct entity? Comparison of clinical and laboratory findings in MCTD, SLE, PSS, and RA patients. Clin Rheumatol 8:29–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02031065

LeRoy EC, Maricq HR, Kahaleh MB (1980) Undifferentiated connective tissue syndromes. Arthritis Rheum 23:341–343. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.1780230312

Nishioka R, Zoshima T, Hara S, Suzuki Y, Ito K, Yamada K, Nakashima A, Tani Y, Kawane T, Hirata M, Mizushima I, Kawano M (2021) Urinary abnormality in mixed connective tissue disease predicts development of other connective tissue diseases and decrease in renal function. Mod Rheumatol. https://doi.org/10.1080/14397595.2021.1899602

Hetlevik SO, Flatø B, Rygg M, Nordal EB, Brunborg C, Hetland H, Lilleby V (2017) Long-term outcome in juvenile-onset mixed connective tissue disease: a nationwide Norwegian study. Ann Rheum Dis 76:159–165. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209522

Frandsen PB, Kriegbaum NJ, Ullman S, Høier-Madsen M, Wiik A, Halberg P (1996) Follow-up of 151 patients with high-titer U1RNP antibodies. Clin Rheumatol 15:254–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02229703

Alves MR, Isenberg DA (2020) “Mixed connective tissue disease”: a condition in search of an identity. Clin Exp Med 20:159–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10238-020-00606-7

Swanton J, Isenberg D (2005) Mixed connective tissue disease: still crazy after all these years. Rheum Dis Clin N Am 31:421–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdc.2005.04.009

Carpintero M, Martinez L, Fernandez I, Romero AG, Mejia C, Zang Y, Hoffman R, Greidinger E (2015) Diagnosis and risk stratification in patients with anti-RNP autoimmunity. Lupus. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203315575586

Reichlin M (1976) Problems in differentiating SLE and mixed connective-tissue disease. N Engl J Med 295:1194–1195. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM197611182952112

van den Hoogen FH, Spronk PE, Boerbooms AM, Bootsma H, de Rooij DJ, Kallenberg CG, van de Putte LB (1994) Long-term follow-up of 46 patients with anti-(U1)snRNP antibodies. Br J Rheumatol 33:1117–1120. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/33.12.1117

Migliorini P, Baldini C, Rocchi V, Bombardieri S (2005) Anti-Sm and anti-RNP antibodies. Autoimmunity 38:47–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/08916930400022715

Lemerle J, Renaudineau Y (2016) Anti-Sm and Anti-U1-RNP antibodies: an update. Lupus Open Access. 1:1–4. https://doi.org/10.35248/2684-1630.16.1.e104

Burdt MA, Hoffman RW, Deutscher SL, Wang GS, Johnson JC, Sharp GC (1999) Long-term outcome in mixed connective tissue disease: longitudinal clinical and serologic findings. Arthritis Rheum 42:899–909. https://doi.org/10.1002/1529-0131(199905)42:5%3c899::AID-ANR8%3e3.0.CO;2-L

Aringer M, Steiner G, Smolen JS (2005) Does mixed connective tissue disease exist? Yes. Rheum Dis Clin N Am 31:411–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdc.2005.04.007

Tani C, Carli L, Vagnani S, Talarico R, Baldini C, Mosca M, Bombardieri S (2014) The diagnosis and classification of mixed connective tissue disease. J Autoimmun 48–49:46–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.008

Ciang NCO, Pereira N, Isenberg DA (2017) Mixed connective tissue disease-enigma variations? Rheumatol Oxf Engl 56:326–333. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kew265

Barsotti S, Orlandi M, Codullo V, Di Battista M, Lepri G, Della Rossa A, Guiducci S (2019) One year in review 2019: systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 37(Suppl 119):3–14

Tanaka Y (2020) State-of-the-art treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Int J Rheum Dis 23:465–471. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185X.13817

Sparks JA (2019) Rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Intern Med 170:ITC1–ITC16. https://doi.org/10.7326/AITC201901010

Fanouriakis A, Kostopoulou M, Alunno A, Aringer M, Bajema I, Boletis JN, Cervera R, Doria A, Gordon C, Govoni M, Houssiau F, Jayne D, Kouloumas M, Kuhn A, Larsen JL, Lerstrøm K, Moroni G, Mosca M, Schneider M, Smolen JS, Svenungsson E, Tesar V, Tincani A, Troldborg A, van Vollenhoven R, Wenzel J, Bertsias G, Boumpas DT (2019) update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 78(2019):736–745. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215089

Didier K, Bolko L, Giusti D, Toquet S, Robbins A, Antonicelli F, Servettaz A (2018) Autoantibodies associated with connective tissue diseases: what meaning for clinicians? Front Immunol 9. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.00541 (accessed 6 Feb 2022

Anderson SG, Bentzon MW, Houba V, Krag P (1970) International reference preparation of rheumatoid arthritis serum. Bull World Health Organ 42:311–318

Sammaritano LR (2020) Antiphospholipid syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 34:101463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2019.101463

Petri M, Orbai A-M, Alarcón GS, Gordon C, Merrill JT, Fortin PR, Bruce IN, Isenberg D, Wallace DJ, Nived O, Sturfelt G, Ramsey-Goldman R, Bae S-C, Hanly JG, Sánchez-Guerrero J, Clarke A, Aranow C, Manzi S, Urowitz M, Gladman D, Kalunian K, Costner M, Werth VP, Zoma A, Bernatsky S, Ruiz-Irastorza G, Khamashta MA, Jacobsen S, Buyon JP, Maddison P, Dooley MA, van Vollenhoven RF, Ginzler E, Stoll T, Peschken C, Jorizzo JL, Callen JP, Lim SS, Fessler BJ, Inanc M, Kamen DL, Rahman A, Steinsson K, Franks AG, Sigler L, Hameed S, Fang H, Pham N, Brey R, Weisman MH, McGwin G, Magder LS (2012) Derivation and validation of the systemic lupus international collaborating clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 64:2677–2686. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.34473

Kay J, Upchurch KS (2012) ACR/EULAR 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria. Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 51(Suppl 6):5–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kes279

Shiboski CH, Shiboski SC, Seror R, Criswell LA, Labetoulle M, Lietman TM, Rasmussen A, Scofield H, Vitali C, Bowman SJ, Mariette X, International Sjögren’s Syndrome Criteria Working Group (2016) American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Classification Criteria for Primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a consensus and data-driven methodology involving three international patient cohorts. Arthritis Rheumatol Hoboken NJ. 69(2017):35–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.39859

Bajema IM, Wilhelmus S, Alpers CE, Bruijn JA, Colvin RB, Cook HT, D’Agati VD, Ferrario F, Haas M, Jennette JC, Joh K, Nast CC, Noël L-H, Rijnink EC, Roberts ISD, Seshan SV, Sethi S, Fogo AB (2018) Revision of the International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society classification for lupus nephritis: clarification of definitions, and modified National Institutes of Health activity and chronicity indices. Kidney Int 93:789–796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2017.11.023

van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, Johnson SR, Baron M, Tyndall A, Matucci-Cerinic M, Naden RP, Medsger TA, Carreira PE, Riemekasten G, Clements PJ, Denton CP, Distler O, Allanore Y, Furst DE, Gabrielli A, Mayes MD, van Laar JM, Seibold JR, Czirjak L, Steen VD, Inanc M, Kowal-Bielecka O, Müller-Ladner U, Valentini G, Veale DJ, Vonk MC, Walker UA, Chung L, Collier DH, Ellen Csuka M, Fessler BJ, Guiducci S, Herrick A, Hsu VM, Jimenez S, Kahaleh B, Merkel PA, Sierakowski S, Silver RM, Simms RW, Varga J, Pope JE (2013) classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American college of rheumatology/European league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 72(2013):1747–1755. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204424

Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery J-L, Gibbs S, Lang I, Torbicki A, Simonneau G, Peacock A, VonkNoordegraaf A, Beghetti M, Ghofrani A, Gomez Sanchez MA, Hansmann G, Klepetko W, Lancellotti P, Matucci M, McDonagh T, Pierard LA, Trindade PT, Zompatori M, Hoeper M, ESC Scientific Document Group (2016) 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the joint task force for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J 37:67–119. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv317

Kondoh Y, Makino S, Ogura T, Suda T, Tomioka H, Amano H, Anraku M, Enomoto N, Fujii T, Fujisawa T, Gono T, Harigai M, Ichiyasu H, Inoue Y, Johkoh T, Kameda H, Kataoka K, Katsumata Y, Kawaguchi Y, Kawakami A, Kitamura H, Kitamura N, Koga T, Kurasawa K, Nakamura Y, Nakashima R, Nishioka Y, Nishiyama O, Okamoto M, Sakai F, Sakamoto S, Sato S, Shimizu T, Takayanagi N, Takei R, Takemura T, Takeuchi T, Toyoda Y, Yamada H, Yamakawa H, Yamano Y, Yamasaki Y, Kuwana M, Joint committee of Japanese Respiratory Society and Japan College of Rheumatology (2021) 2020 guide for the diagnosis and treatment of interstitial lung disease associated with connective tissue disease. Respir Investig 59:709–740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resinv.2021.04.011

Lundberg IE, de Visser M, Werth VP (2018) Classification of myositis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 14:269–278. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2018.41

Kontzias A, Barkhodari A, Yao Q (2020) Pericarditis in systemic rheumatologic diseases. Curr Cardiol Rep 22:142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-020-01415-w

Bautista-Vargas M, Vivas AJ, Tobón GJ (2020) Minor salivary gland biopsy: Its role in the classification and prognosis of Sjögren’s syndrome. Autoimmun Rev 19:102690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102690

Vlachoyiannopoulos PG, Guialis A, Tzioufas G, Moutsopoulos HM (1996) Predominance of IgM anti-U1RNP antibodies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Br J Rheumatol 35:534–541. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/35.6.534

Abdelgalil-Ali-Ahmed S, Adam Essa ME, Ahmed AF, Elagib EM, Ahmed Eltahir NI, Awadallah H, Hassan A, Khair ASM, Ebad MAB (2021) Incidence and clinical pattern of mixed connective tissue disease in Sudanese patients at Omdurman Military Hospital: hospital-based study. Open Access Rheumatol Res Rev. 13:333–341. https://doi.org/10.2147/OARRR.S335206

Bodolay E, Szekanecz Z, Dévényi K, Galuska L, Csípo I, Vègh J, Garai I, Szegedi G (2005) Evaluation of interstitial lung disease in mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD). Rheumatol Oxf Engl 44:656–661. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keh575

Khanna D, Gladue H, Channick R, Chung L, Distler O, Furst DE, Hachulla E, Humbert M, Langleben D, Mathai SC, Saggar R, Visovatti S, Altorok N, Townsend W, FitzGerald J, McLaughlin VV (2013) Scleroderma Foundation and Pulmonary Hypertension Association, recommendations for screening and detection of connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Arthritis Rheum 65:3194–3201. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.38172

Alpert MA, Goldberg SH, Singsen BH, Durham JB, Sharp GC, Ahmad M, Madigan NP, Hurst DP, Sullivan WD (1983) Cardiovascular manifestations of mixed connective tissue disease in adults. Circulation 68:1182–1193. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.68.6.1182

Szodoray P, Hajas A, Kardos L, Dezso B, Soos G, Zold E, Vegh J, Csipo I, Nakken B, Zeher M, Szegedi G, Bodolay E (2012) Distinct phenotypes in mixed connective tissue disease: subgroups and survival. Lupus 21:1412–1422. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203312456751

Carpintero MF, Martinez L, Fernandez I, Romero ACG, Mejia C, Zang YJ, Hoffman RW, Greidinger EL (2015) Diagnosis and risk stratification in patients with anti-RNP autoimmunity. Lupus 24:1057–1066. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203315575586

Mesa A, Somarelli JA, Wu W, Martinez L, Blom MB, Greidinger EL, Herrera RJ (2013) Differential immunoglobulin class-mediated responses to components of the U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle in systemic lupus erythematosus and mixed connective tissue disease. Lupus 22:1371–1381. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203313508444

Somarelli J, Mesa A, Rodriguez R, Avellan R, Martinez L, Zang Y, Greidinger E, Herrera R (2011) Epitope mapping of the U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and mixed connective tissue disease. Lupus 20:274–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203310387180

Chebbi PP, Goel R, Ramya J, Gowri M, Herrick A, Danda D (2021) Nailfold capillaroscopy changes associated with anti-RNP antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-021-04894-4

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by IE, HdB, KK and DP. The first draft of the manuscript was written by IE and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Caen Normandie and of the Caen University Hospital Center (Approval No. 2020-1489).

Consent to participate

All patients were informed of their retrospective inclusion in this study in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Caen Normandie and of the Caen University Hospital Center.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Elhani, I., Khoy, K., Mariotte, D. et al. The diagnostic challenge of patients with anti-U1-RNP antibodies. Rheumatol Int 43, 509–521 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-022-05161-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-022-05161-w