Abstract

Diet is a modifiable factor implicated in chronic systemic inflammation, and the mediterranean dietary pattern is considered to be a healthy model in terms of morbidity and mortality. The main aim of this study was to evaluate the adherence to the mediterranean diet in patients with Psoriatic Arthritis (PsA) and its impact on disease activity. A cross-sectional observational study was conducted in a cohort of 211 consecutive PsA patients. We evaluated PsA activity by disease activity index for PSoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA) and composite psoriatic disease activity index (CPDAI). The NCEP-ACT III criteria were used to identify subjects with MetS, and in each subject, we evaluated body mass index (BMI). A validated 14-item questionnaire for the assessment of adherence to the mediterranean diet (PREDIMED) was recorded for all the enrolled subjects. Patients showed a median age of 55 (48–62) and disease duration was 76 (36–120) months. 27.01% of patients were classified as having MetS. The median of the mediterranean diet score (MDS) was 7 (6–9). A moderate adherence to mediterranean diet was found in 66.35% of the entire cohort; 15.64% and 18.01% of the patients showed low- and high adherence to the dietary pattern, respectively. We found a negative association between DAPSA and adherence to mediterranean diet (B = − 3.291; 95% CI − 5.884 to − 0.698). DAPSA was positively associated with BMI (B = 0.332; 95% CI 0.047–0.618) and HAQ ( B = 2.176; 95% CI 0.984–3.368). Results from our study evidenced that in PsA patients, higher levels of disease activity as measured by DAPSA correlated with low adherence to mediterranean diet, suggesting potential benefit of antinflammatory properties of this dietary pattern.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is an inflammatory arthropathy associated with psoriasis and heterogenous manifestations [1, 2]. Among those, atherosclerosis, obesity, and metabolic syndrome (MetS) have been described as possible phenotypic aspects of the underlining inflammatory process [3,4,5].

However, high severity of PsA and increased prevalence of cardiovascular (CV) disease and its risk factors have also been explained by unhealthy lifestyle and nutritional aspects [6].

Diet is a modifiable factor implicated in chronic systemic inflammation, as well in psoriatic disease. Nevertheless, the relationship between dietary pattern and PsA incidence and severity has been scarcely studied [7, 8]. Particularly, it has been demonstrated that PsA patients have an excessive consumption of calories, lipids, fatty acids, and cholesterol [9]. Furthermore, very low energy diet along with short-term weight loss treatment has been found to be associated with significant positive effects on articular and entheseal severity in PsA patients with obesity [10].

Intermittent fasting (Ramadan fasting) has been reported to be associated with beneficial effects on PsA disease activity, expressed by disease activity index for Psoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA) and bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index (BASDAI), enthesitis, and dactylitis, independently by weight loss [11]. This has been hypothesized related to impact of fasting on proinflammatory mechanisms [11].

Moreover, obese PsA patients under biological therapy receiving hypocaloric diet with a weight loss > 5% had more frequently a minimal disease activity than those with weight loss < 5% [12].

Among dietary patterns, the Mediterranean diet is considered to be a healthy model in terms of morbidity and mortality [13]. It is characterized by a high intake of fruits, vegetables, legumes cereals, and fish, which are rich in vitamins, anti-oxidant, and anti-inflammatory nutrients. This dietary pattern comprises also low–moderate intake of dairy products, eggs, and poultry as well as low consumption of sweets, red meat, and wine. The main source of dietary fat is represented by monounsaturated fatty acids’ compounds contained by the extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) [14].

Main results of studies on Mediterranean diet and psoriasis suggest an independent inverse association between compliance with the Mediterranean diet and psoriasis occurrence, severity, and quality of life [15,16,17,18].

To our knowledge, there are no studies investigating correlation between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and severity of PsA.

For this reason, we conducted a multicentric cross-sectional observational study to evaluate the adherence to the Mediterranean diet in patients with PsA and its impact on disease activity.

Patients and methods

A multicentric cross-sectional observational study has been conducted in a cohort of PsA patients of five Rheumatology Units from the University of Naples Federico II, Naples (Italy); University of L’Aquila, L’Aquila (Italy); Università Campus Bio-Medico, Rome (Italy); University of Rome Tor Vergata, Rome (Italy); and Sant’Andrea Hospital, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome (Italy).

Consecutive PsA patients attending the five outpatient Rheumatology Units were enrolled from January 2019 to May 2019. The study was approved on 22/06/2015 by the Federico II Naples Hospital Local Ethics Committee (protocol no: 15-126) and was conducted in conformity with the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. A written informed consent for the anonymous use of data was obtained from all participants.

Inclusion criteria were both sexes, age > 18 years, and the fulfilment of CASPAR (Classification criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis) criteria [19, 20]. The exclusion criteria were: (1) current use of corticosteroids, (2) recent use of at least 6 months of corticosteroids, and (3) endocrinopathies and use of progestins.

In detail, the following data were recorded for each PsA patient: age, gender, vital signs, PsA duration, previous and/or actual treatments, and current comorbidities.

Assessment of disease activity

To measure PsA activity, the composite disease severity scores, DAPSA, and composite psoriatic disease activity index (CPDAI) were assessed.

For DAPSA, we summed the following variables: Tender and Swollen Joints Count (TJC68, SJC66), patient global assessment (PtGA), patient pain on a 10 cm visual analogue scale (VAS), and C-reactive protein (CRP) [21, 22]. We measured CPDAI score by the use of 68 TJC and 66 SJC, dactylitis (count of digit involved), enthesitis [leeds enthesitis index (LEI)], skin involvement by psoriasis severity index (PASI) and dermatology life quality index questionnaire (DLQI), health assessment questionnaire (HAQ), and axial involvement by BASDAI [23].

We also assessed axial involvement by the use of the single measure bath ankylosing spondylitis functional index (BASFI).

Assessment of metabolic parameters

Anthropometric parameters recorded were height and weight. In each subject, weight and height were used to calculate the BMI [weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2), kg/m2]. The degree of obesity was established according to a scale based on BMI cut-off points: 25 ≤ 30 kg/m2 (overweight), 30–34.9 kg/m2 (grade I obesity), 35–39.9 kg/m2 (grade II obesity), and ≥ 40 kg/m2 (grade III obesity or severe obesity), respectively.

For the definition of MetS, we used the following parameters: serum concentrations of total cholesterol (TC), HDL-C, TG and plasma glucose concentration, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Patients with a blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg or those on anti-hypertensive drugs were considered as high blood pressure sufferers. Then, the NCEP-ACT III criteria were used to identify subjects with MetS [24].

A validated 14-item questionnaire for the assessment of adherence to the Mediterranean Diet (PREDIMED) [25] was recorded for all the enrolled subjects during a face-to-face interview between the patient and a rheumatologist. Briefly, for each item was assigned score 1 and 0; PREDIMED score was calculated as follows: 0–5, lowest adherence; 6–9, moderate adherence; ≥ 10–14, highest adherence.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were described by median (25–75th Pctl), while categorical variables were described as percentages (%). The Shapiro–Wilk test has been used to test the normality of data. Fisher’s exact test has been used for analysis of contingency table, while Kruskal–Wallis has been used to compare ranks. Using DAPSA as dependent variable, a multiple linear regression analysis model was set up considering for multivariable analysis every variable with p < 0.1 in univariate analysis. For all the analysis, STATA v.14 has been used.

Results

On the basis of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 211 subjects were included in the study.

Main demographic, anthropometric and clinical characteristics of the study population are reported in Table 1.

The patient population was Caucasian (100%) with a large preponderance of females (62.09%) and a median age of 55 (48–62). Disease duration (namely, time from diagnosis of PsA) was 76 (36–120) months. According to NCEP-ACT III criteria, 27.01% of patients were classified as having MetS.

Conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) were used by 41.71% of the patients, and particularly, 28.44% were receiving methotrexate, 9.48% sulfasalazine, 1.42% cyclosporine A, and 2.37% leflunomide. Biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs) or the phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) inhibitor, apremilast, were used by 60.66% of the patients and particularly, 0.9% infliximab, 9.48% etanercept, 16.11% adalimumab, 0.95% certolizumab pegol, 13.74% golimumab, 9.48% ustekinumab, 3.32% secukinumab, and 6.64% apremilast.

The measures of PsA activity showed a median DAPSA value of 16.33 (7.3–24.1) and CPDAI of 3 (2–6).

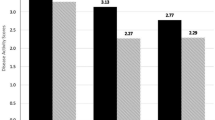

The median of the mediterranean diet score (MDS) was 7 (6–9). A moderate adherence to Mediterranean Diet was found in 66.35% of the entire cohort; 15.64% and 18.01% of the patients showed low and high adherences to the dietary pattern, respectively.

There were no significant differences in any of the variables between males and females.

A significant difference in age among classes of adherence to Mediterranean diet (low, moderate, or high adherence) was found (p = 0.04). Particularly, we found a significant difference in age between patients in low adherence to Mediterranean diet [51 (45–58) years] compared with patients with high adherence [58 (52–62) years] (p = 0.01).

Using the Kruskal–Wallis test, no significant difference in CRP levels among the three classes of adherence to Mediterranean diet has been demonstrated (p = 0.2) (Table 2).

Results of the univariate and multivariate linear regression analyses examining the factors associated with disease activity as measured by DAPSA are shown in Table 3. Intriguingly, the adjusted linear regression model showed a negative association between DAPSA and adherence to Mediterranean diet intended as classes (B = − 3.291; 95% CI − 5.884 to − 0.698). Moreover, DAPSA were negatively associated with male sex (B = − 4.999; 95% CI − 8.120 to − 1.877) and the treatment with bDMARDs or apremilast (B = − 5.326; 95% CI − 8.381 to − 2.271), whereas it was positively associated with BMI B = 0.332; 95% CI 0.047–0.618) and HAQ (B = 2.176; 95% CI 0.984–3.368).

Discussion

The aim of the study was to investigate the correlation between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and PsA activity, as measured by DAPSA and CPDAI. In particular, the study was conducted highlight possible PsA activity differences between patients grouped according to the class of adherence to Mediterranean diet.

Our cohort was represented by more than 200 patients, mainly represented by females (62%). Enrolled patients showed a long disease duration (above 6 years) and above 27% of patients were classified as having MetS.

At time of evaluation, we found low/moderate disease activity as evaluated by CPDAI [3 (2–6)] and DAPSA [16.33 (7.3–24.1)]. These results were expected as 60% of patients were taking bDMARDs or apremilast treatment and the remaining population was taking csDMARDs’ therapy.

When we assessed the adherence to the Mediterranean Diet by the PREDIMED questionnaire, a moderate or high adherence to Mediterranean Diet was found in more than half of the enrolled patients. Low adherence to the dietary pattern was found in above 15.64% of the cohort and this correlated with a high PsA activity, as measured by DAPSA.

The univariate analysis failed in demonstrating an association between disease activity and the adherence to Mediterranean diet. Despite this, in a multivariate model adjusted for sex, BMI, HAQ, and type of pharmacological treatment, we found that a higher PsA activity, as measured by DAPSA, was associated with low adherence to Mediterranean diet. The calculation of DAPSA included CRP; however, in this study, CRP levels were not significant different among the classes of adherence.

Our findings are concordant with results from studies showing an inverse association between compliance with the Mediterranean diet and psoriasis severity, and inflammatory state [15,16,17,18, 26].

However, further studies are needed for evaluating the impact of Mediterranean Diet on inflammatory parameters in PsA patients. Until today, the current study represents the first one focusing on Mediterranean Diet in PsA. Evidence to support the association between lower inflammation and other specific dietary patterns is limited [27]. Among those, an intermittent fasting has been reported to be associated with positive effects on PsA severity as measured by DAPSA; in addition, a very low energy diet with short-term weight loss showed a significant positive effect on articular and entheseal severity in obese PsA patients [10, 11]. Weight loss achieved by diet, or also in concomitance of physical exercise, has been reported more effective than anti-inflammatory therapy alone in improving the symptoms and systemic inflammation with significant reductions in the serum levels of CRP and several proinflammatory molecules in obese PsA patients [28].

Our study also showed that DAPSA resulted positively associated with BMI, sustaining the possible link between the severity of the disease, metabolic manifestations and dietary pattern [29]. This is in line with recent evidences in which PsA inflammation and obesity are considered as strictly interconnected [30, 31]. However, the underlying mechanisms linking obesity and PsA severity have not yet been completely clarified. Indeed, if on one hand, obesity has been reported a factor associated with a systemic low-grade inflammation, on the other hand, elevated BMI could sustain an elevated articular biomechanical stress with an increased inflammatory response [32, 33]. It is plausible that these two mechanisms could concur to promote inflammatory processes in psoriatic disease [32, 33].

Diet is a modifiable factor implicated in chronic systemic inflammation. Mediterranean diet is considered to be a healthy model in terms of morbidity and mortality [13, 14]. Several studies have evidenced the anti-inflammatory effects of the Mediterranean diet, as it could be reducing circulating proinflammatory cytokines [34,35,36,37,38].

The anti-inflammatory properties on arthritis could be explained by different mechanisms, mainly represented by effects of several compounds of Mediterranean Diet, such as oleic acid, monounsaturated fatty acids, polyphenol extract, anti-oxidant agents, and the inhibitor of cyclooxygenase-2, resveratrol [39, 40]. Furthermore, dietary fiber favoring beneficial effects on gut microbiota could have a role in improving the regulation of gut immune responses [41,42,43,44,45].

Results from our study open a new research area on the possible anti-inflammatory role of the Mediterranean dietary pattern in PsA. It has been yet highlighted that lifestyle interventions as well dietary modification should be implemented for PsA patients [46].

In 2018, the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation proposed evidence-based dietary recommendations for adults with psoriasis and PsA. In these recommendations, it is suggested dietary weight reduction with a hypocaloric diet in overweight and obese PsA patients. It is recommended also that adults with PsA supplement their standard medical therapies with dietary interventions to reduce disease severity [47].

The Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) recommends that all PsA patients should be encouraged to achieve and maintain a healthy body weight [48] and an appropriate dietary pattern, by Mediterranean Diet, could represent a useful strategy for this aim.

Furthermore, the identification of PsA patients with a high inflammatory pattern and cardiometabolic manifestations could represent a key step to implement preventive approaches, such as dietary modifications along with appropriate pharmacological strategies. The whole diet approach seems particularly promising to reduce the inflammation associated with MetS and this can be a promising strategy also in psoriatic disease [49].

The main limitations of the study were represented by the absence of patients naïve to cs- and bDMARDs and by the cross-sectional design that does not allow to fully establish if adherence to the Mediterranean diet is related to the severity of the disease.

Among advantages of our study, DAPSA represents a valid composite disease activity measure, and in comparison with CPDAI, it is recognized to better correlate with subclinical inflammatory severity [50,51,52,53]. Furthermore, we excluded patients with endocrinopathies and current or recent treatment with glucocorticoids and progestins, for avoiding factors interfering with components of MetS and dietary intake.

On the basis of our findings, we hypothesized that Mediterranean diet could be considered a healthy model for PsA patients, but further studies are needed.

These could evaluate the relation between the adherence to Mediterranean Diet and PsA activity also by the use of other validated questionnaires, such as the MedDietScore, the Mediterranean Lifestyle (MEDLIFE) index, and the questionnaire derived from the Spanish EPIC Cohort Study (Relative Mediterranean Diet Score) [54,55,56,57].

Conclusion

In conclusion, results from our cohort have evidenced that high PsA activity, as measured by DAPSA, is associated with low adherence to Mediterranean Diet, suggesting that PsA patients could benefit of antinflammatory properties of this dietary pattern.

Further studies on larger sample size and naive patients are advocated to identify a possible impact of Mediterranean dietary pattern on disease severity.

Data availability

All data relevant to the study are included in the article.

References

Caso F, Costa L, Atteno M, Del Puente A, Cantarini L, Lubrano E, Scarpa R (2014) Simple clinical indicators for early Psoriatic Arthritis detection. Springerplus 3:759

Scarpa R, Caso F, Costa L, Peluso R, Del Puente A, Olivieri I (2017) Psoriatic disease 10 years later. J Rheumatol 44:1298–1301

Costa L, Caso F, D’Elia L, Atteno M, Peluso R, Del Puente A, Strazzullo P, Scarpa R (2012) Psoriatic Arthritis is associated with increased arterial stiffness in the absence of known cardiovascular risk factors: a case control study. Clin Rheumatol 31:711–715

Costa L, Caso F, Ramonda R, Del Puente A, Cantarini L, Darda MA, Caso P, Lorenzin M, Fiocco U, Punzi L, Scarpa R (2015) Metabolic syndrome and its relationship with the achievement of minimal disease activity state in Psoriatic Arthritis patients: an observational study. Immunol Res 61:147–153

Caso F, Del Puente A, Oliviero F, Peluso R, Girolimetto N, Bottiglieri P, Foglia F, Benigno C, Tasso M, Punzi L, Scarpa R, Costa L (2018) Metabolic syndrome in Psoriatic Arthritis: the interplay with cutaneous involvement. Evidences from literature and a recent cross-sectional study. Clin Rheumatol 37:579–586

Peluso R, Caso F, Tasso M, Sabbatino V, Lupoli R, Dario Di Minno MN, Ursini F, Costa L, Scarpa R (2019) Biomarkers of subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with Psoriatic Arthritis. Open Access Rheumatol 11:143–156

Minihane AM, Vinoy S, Russell WR et al (2015) Low-grade inflammation, diet composition and health: current research evidence and its translation. Br J Nutr 114:999–1012

Daïen CI, Sellam J (2015) Obesity and inflammatory arthritis: impact on occurrence, disease characteristics and therapeutic response. RMD Open 1:e000012

Solis MY, de Melo NS, Macedo ME, Carneiro FP, Sabbag CY, Lancha Júnior AH, Frangella VS (2012) Nutritional status and food intake of patients with systemic psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis associated. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 10:44–52

Klingberg E, Bilberg A, Björkman S, Hedberg M, Jacobsson L, Forsblad-d’Elia H, Carlsten H, Eliasson B, Larsson I (2019) Weight loss improves disease activity in patients with Psoriatic Arthritis and obesity: an interventional study. Arthritis Res Ther 21:17

Adawi M, Damiani G, Bragazzi NL, Bridgewood C, Pacifico A, Conic RRZ, Morrone A, Malagoli P, Pigatto PDM, Amital H, McGonagle D, Watad A (2019) The Impact of intermittent fasting (Ramadan Fasting) on Psoriatic Arthritis disease activity, enthesitis, and dactylitis: a multicentre study. Nutrients. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11030601

Di Minno MN, Peluso R, Iervolino S, Russolillo A, Lupoli R, Scarpa R, CaRRDs Study Group (2014) Weight loss and achievement of minimal disease activity in patients with Psoriatic Arthritis starting treatment with tumour necrosis factor α blockers. Ann Rheum Dis 73:1157–1162

Sofi F, Macchi C, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A (2014) Mediterranean diet and health status: an updated meta-analysis and a proposal for a literature-based adherence score. Public Health Nutr 17:2769–2782

Petersson S, Philippou E, Rodomar C, Nikiphorou E (2018) The Mediterranean diet, fish oil supplements and Rheumatoid arthritis outcomes: evidence from clinical trials. Autoimmun Rev 17:1105–1114

Korovesi A, Dalamaga M, Kotopouli M, Papadavid E (2019) Adherence to the Mediterranean diet is independently associated with psoriasis risk, severity, and quality of life: a cross-sectional observational study. Int J Dermatol 58:e164–e165

Molina-Leyva A, Cuenca-Barrales C, Vega-Castillo JJ, Ruiz-Carrascosa JC, Ruiz-Villaverde R (2019) Adherence to Mediterranean diet in Spanish patients with psoriasis: cardiovascular benefits? Dermatol Ther 32:e12810

Phan C, Touvier M, Kesse-Guyot E, Adjibade M, Hercberg S, Wolkenstein P, Chosidow O, Ezzedine K, Sbidian E (2018) Association between mediterranean anti-inflammatory dietary profile and severity of psoriasis: results from the NutriNet-Santé Cohort. JAMA Dermatol 154:1017–1024

Barrea L, Balato N, Di Somma C, Macchia PE, Napolitano M, Savanelli MC, Esposito K, Colao A, Savastano S (2015) Nutrition and psoriasis: is there any association between the severity of the disease and adherence to the Mediterranean diet? J Transl Med 13:18

Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P, Marchesoni A, Mease P, Mielants H, CASPAR Study Group (2006) Classification criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum 54:2665–2673

Tillett W, Costa L, Jadon D, Wallis D, Cavill C, McHugh J, Korendowych E, McHugh N (2012) The classification for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) criteria—a retrospective feasibility, sensitivity, and specificity study. J Rheumatol 39:154–156

Scarpa R, Caso F (2018) Spondyloarthritis: which composite measures to use in Psoriatic Arthritis? Nat Rev Rheumatol 14:125–126

Schoels M, Aletaha D, Funovits J et al (2010) Application of the DAREA/DAPSA score for assessment of disease activity in Psoriatic Arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 69:1441–1447

Mumtaz A, Gallagher P, Kirby B, Waxman R, Coates LC, Veale JD, Helliwell P, FitzGerald O (2011) Development of a preliminary composite disease activity index in Psoriatic Arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 70:272–277

Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (2001) Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 285:2486–2497

Martínez-González MA, García-Arellano A, Toledo E, Salas-Salvadó J, Buil-Cosiales P, Corella D, Covas MI, Schröder H, Arós F, Gómez-Gracia E, Fiol M, Ruiz-Gutiérrez V, Lapetra J, Lamuela-Raventos RM, Serra-Majem L, Pintó X, Muñoz MA, Wärnberg J, Ros E, Estruch R, PREDIMED Study Investigators (2012) A 14-item Mediterranean diet assessment tool and obesity indexes among high-risk subjects: the PREDIMED trial. PLoS ONE 7:e43134

Bonaccio M, Cerletti C, Iacoviello L, de Gaetano G (2015) Mediterranean diet and low-grade subclinical inflammation: the Moli-sani study. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets 15:18–24

Almodóvar R, Zarco P, Otón T, Carmona L (2018) Effect of weight loss on activity in Psoriatic Arthritis: a systematic review. Reumatol Clin 14:207–210

Abou-Raya A, Abou-Raya S, Helmii M (2014) Effect of exercise and dietary weight loss on symptoms and systemic inflammation inobese adults with Psoriatic Arthritis: randomized controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-eular.2760

Chimenti MS, Caso F, Alivernini S, De Martino E, Costa L, Tolusso B, Triggianese P, Conigliaro P, Gremese E, Scarpa R, Perricone R (2019) Amplifying the concept of Psoriatic Arthritis: the role of autoimmunity in systemic psoriatic disease. Autoimmun Rev 18:565–575

Costa L, Ramonda R, Ortolan A, Favero M, Foti R, Visalli E, Rossato M, Cacciapaglia F, Lapadula G, Scarpa R (2019) Psoriatic Arthritis and obesity: the role of anti-IL-12/IL-23 treatment. Clin Rheumatol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04663-6

Caso F, Postiglione L, Covelli B, Ricciardone M, Di Spigna G, Formisano P, D’Esposito V, Girolimetto N, Tasso M, Peluso R, Navarini L, Ciccozzi M, Margiotta DPE, Oliviero F, Afeltra A, Punzi L, Del Puente A, Scarpa R, Costa L (2019) Pro-inflammatory adipokine profile in Psoriatic Arthritis: results from a cross-sectional study comparing PsA subset with evident cutaneous involvement and subset “sine psoriasis”. Clin Rheumatol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04619-w

Eder L, Abji F, Rosen CF, Chandran V, Gladman DD (2017) The association between obesity and clinical features of Psoriatic Arthritis: a case-control study. J Rheumatol 44:437–443

McGonagle D, Tan AL, Benjamin M (2008) The biomechanical link between skin and joint disease in psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis: what every dermatologist needs to know. Ann Rheum Dis 67:1–4

Casas R, Sacanella E, Estruch R (2014) The immune protective effect of the Mediterranean diet against chronic low-grade inflammatory diseases. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets 14:245–254

Gotsis E, Anagnostis P, Mariolis A, Vlachou A, Katsiki N, Karagiannis A (2015) Health benefits of the Mediterranean Diet: an update of research over the last 5 years. Angiology 66:304–318

Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G (2014) Mediterranean dietary pattern, inflammation and endothelial function: a systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention trials. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 24:929–939

Schwingshackl L, Missbach B, König J, Hoffmann G (2015) Adherence to a mediterranean diet and risk of diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Nutr. 18:1292–1299

Salas-Salvadó J, Garcia-Arellano A, Estruch R, Marquez-Sandoval F, Corella D, Fiol M, Gómez-Gracia E, Viñoles E, Arós F, Herrera C, Lahoz C, Lapetra J, Perona JS, Muñoz-Aguado D, Martínez-González MA, Ros E, PREDIMED Investigators (2008) Components of the mediterranean-type food pattern and serum inflammatory markers among patients at high risk for cardiovascular disease. Eur J Clin Nutr 62:651–659

Rosillo MA, Sanchez-Hidalgo M, Sanchez-Fidalgo S, Aparicio-Soto M, Villegas I, Alarcon-de-la-Lastra C (2016) Dietary extra-virgin olive oil prevents inflammatory response and cartilage matrix degradation in murine collagen-induced arthritis. Eur J Nutr 55:315–325

Rosillo MA, Alcaraz MJ, Sanchez-Hidalgo M, Fernandez-Bolanos JG, Alarcon-de-laLastra C, Ferrandiz ML (2014) Anti-inflammatory and joint protective effects of extravirgin olive-oil polyphenol extract in experimental arthritis. J Nutr Biochem 25:1275–1281

Chimenti MS, Perricone C, Novelli L, Caso F, Costa L, Bogdanos D, Conigliaro P, Triggianese P, Ciccacci C, Borgiani P, Perricone R (2018) Interaction between microbiome and host genetics in Psoriatic Arthritis. Autoimmun Rev 17:276–283

Scher JU, Ubeda C, Artacho A, Attur M, Isaac S, Reddy SM, Marmon S, Neimann A, Brusca S, Patel T, Manasson J, Pamer EG, Littman DR, Abramson SB (2015) Decreased bacterial diversity characterizes the altered gut microbiota in patients with Psoriatic Arthritis, resembling dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel disease. Arthritis Rheumatol 67:128–139

Chimenti MS, Triggianese P, De Martino E, Conigliaro P, Fonti GL, Sunzini F, Caso F, Perricone C, Costa L, Perricone R (2019) An update on pathogenesis of Psoriatic Arthritis and potential therapeutic targets. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 15:823–836

Zhong D, Wu C, Zeng X, Wang Q (2018) The role of gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of rheumatic diseases. Clin Rheumatol 37:25–34

Oliviero F, Spinella P, Fiocco U, Ramonda R, Sfriso P, Punzi L (2015) How the mediterranean diet and some of its components modulate inflammatory pathways in arthritis. Swiss Med Wkly 145:w14190

Sinnathurai P, Capon A, Buchbinder R, Chand V, Henderson L, Lassere M, March L (2018) Cardiovascular risk management in rheumatoid and Psoriatic Arthritis: online survey results from a national cohort study. BMC Rheumatol. 2:25

Ford AR, Siegel M, Bagel J, Cordoro KM, Garg A, Gottlieb A, Green LJ, Gudjonsson JE, Koo J, Lebwohl M, Liao W, Mandelin AM 2nd, Markenson JA, Mehta N, Merola JF, Prussick R, Ryan C, Schwartzman S, Siegel EL, Van Voorhees AS, Wu JJ, Armstrong AW (2018) Dietary recommendations for adults with psoriasis or Psoriatic Arthritis from the medical board of the national psoriasis foundation: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol 154:934–950

Coates LC, Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, Soriano ER, Laura Acosta-Felquer M, Armstrong AW, Bautista-Molano W, Boehncke WH, Campbell W, Cauli A, Espinoza LR, FitzGerald O, Gladman DD, Gottlieb A, Helliwell PS, Husni ME, Love TJ, Lubrano E, McHugh N, Nash P, Ogdie A, Orbai AM, Parkinson A, O’Sullivan D, Rosen CF, Schwartzman S, Siegel EL, Toloza S, Tuong W, Ritchlin CT (2016) Group for research and assessment of psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis 2015 treatment recommendations for Psoriatic Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 68:1060–1071

Giugliano D, Ceriello A, Esposito K (2006) The effects of diet on inflammation: emphasis on the metabolic syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 48:677–685

Kerschbaumer A, Smolen JS, Aletaha D (2018) Disease activity assessment in patients with Psoriatic Arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 32:401–414

Schoels MM, Aletaha D, Alasti F, Smolen JS (2016) Disease activity in Psoriatic Arthritis (PsA): defining remission and treatment success using the DAPSA score. Ann Rheum Dis 75:811–818

Salaffi F, Ciapetti A, Carotti M, Gasparini S, Gutierrez M (2014) Disease activity in Psoriatic Arthritis: comparison of the discriminative capacity and construct validity of six composite indices in a real world. Biomed Res Int 2014:528105

Husic R, Gretler J, Felber A, Graninger WB, Duftner C, Hermann J, Dejaco C (2014) Disparity between ultrasound and clinical findings in Psoriatic Arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 73:1529–1536

Zaragoza-Martí A, Cabañero-Martínez MJ, Hurtado-Sánchez JA, Laguna-Pérez A, Ferrer-Cascales R (2018) Evaluation of mediterranean diet adherence scores: a systematic review. BMJ Open 8:e019033

Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Stefanadis C (2006) Dietary patterns: a mediterranean diet score and its relation to clinical and biological markers of cardiovascular disease risk. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 16:559–568

Sotos-Prieto M, Moreno-Franco B, Ordovás JM et al (2015) Design and development of an instrument to measure overall lifestyle habits for epidemiological research: the Mediterranean Lifestyle (MEDLIFE) index. Public Health Nutr 18:959–967

Buckland G, González CA, Agudo A, Vilardell M, Berenguer A, Amiano P, Ardanaz E, Arriola L, Barricarte A, Basterretxea M, Chirlaque MD, Cirera L, Dorronsoro M, Egües N, Huerta JM, Larrañaga N, Marin P, Martínez C, Molina E, Navarro C, Quirós JR, Rodriguez L, Sanchez MJ, Tormo MJ, Moreno-Iribas C (2009) Adherence to the mediterranean diet and risk of coronary heart disease in the Spanish EPIC Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol 170:1518–1529

Funding

No specific funding was received for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, the acquisition, and interpretation of data. All authors contributed to the critical review and revision of the manuscript and approved the final version. All the authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. FC study design, data acquisition, statistical analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the first draft of the paper, review, and acceptance; LN study design, data acquisition, statistical analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the first draft of the paper, review, and acceptance; FC study design, data acquisition, interpretation of data, review, and acceptance; APD study design, data acquisition, interpretation of data, review, and acceptance; MSC study design, data acquisition, interpretation of data, review, and acceptance; MT study design, data acquisition, interpretation of data, review, and acceptance; DC study design, data acquisition, interpretation of data, review, and acceptance; PR study design, data acquisition, interpretation of data, review, and acceptance; MC study design, statistical analysis interpretation of data, review, and acceptance; AA study design, data acquisition, interpretation of data, review, and acceptance; BL study design, data acquisition, interpretation of data, review, and acceptance; RP study design, data acquisition, interpretation of data, review, and acceptance; AA study design, data acquisition, interpretation of data, review, and acceptance; RG study design, data acquisition, interpretation of data, review, and acceptance; RS study design, data acquisition, interpretation of data, review, and acceptance; LC study design, data acquisition, interpretation of data, writing of the first draft of the paper, review, and acceptance.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in this work. Francesco Caso: conflict of interest and relationships with pharma agencies—none; Luca Navarini: conflict of interest and relationships with pharma agencies—none; Francesco Carubbi: conflict of interest and relationships with pharma agencies—none; Andrea Picchianti-Diamanti: conflict of interest and relationships with pharma agencies—none; Maria Sole Chimenti: conflict of interest and relationships with pharma agencies—none; Marco Tasso: conflict of interest and relationships with pharma agencies—none; Damiano Currado: conflict of interest and relationships with pharma agencies—none; Piero Ruscitti: conflict of interest and relationships with pharma agencies—PR received speaker honoraria and/or grants from BMS, MSD, Ely Lilly, SOBI and Pfizer outside this work; Massimo Ciccozzi: conflict of interest and relationships with pharma agencies—none; Antonio Annarumma: conflict of interest and relationships with pharma agencies—none; Bruno Laganà: conflict of interest and relationships with pharma agencies—none; Roberto Perricone: conflict of interest and relationships with pharma agencies—none; Antonella Afeltra: conflict of interest and relationships with pharma agencies—none; Roberto Giacomelli: conflict of interest and relationships with pharma agencies—RG received speaker honoraria and/or grants from Abbvie, Roche, Actelion, BMS, MSD, Ely Lilly, SOBI and Pfizer outside this work; Raffaele Scarpa: conflict of interest and relationships with pharma agencies—RS received speaker honoraria and/or grants from Abbvie, Celgene, MSD, Ely Lilly, Novartis, and Pfizer; Luisa Costa: conflict of interest and relationships with pharma agencies—none.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Caso, F., Navarini, L., Carubbi, F. et al. Mediterranean diet and Psoriatic Arthritis activity: a multicenter cross-sectional study. Rheumatol Int 40, 951–958 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-019-04458-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-019-04458-7