Abstract

Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) patients carrying hepatitis C virus (HCV) have higher risk of treatment toxicity and complications. The aim of this study was to assess the impact of HCV in a series of DLBCL patients treated with immunochemotherapy. 321 patients (161 M/160F; median age, 66 years) diagnosed with de novo DLBCL in a single center between 2002 and 2013 were included. Immunodeficiency-related lymphomas were excluded. HCV+ cases were defined by the presence of IgG anti-HCV. Main clinico-biological characteristics and outcome were analyzed according to the viral status. Two hundred ninety patients were HCV− and 31 HCV+. HCV+ patients were older (median age 71 vs. 64 years, P = 0.03), had more often B symptoms (P = 0.013), spleen (P = 0.003), and liver (P = 0.011) involvement, higher rate of early death (<4 months, P = .001), and shorter overall survival (OS). Eleven HCV+ patients had cirrhosis criteria. HCV+ patients with impaired liver function before or during treatment showed inferior OS. Elevated pre-treatment bilirubin correlated also with higher liver toxicity. In a multivariate analysis that included R-IPI score, serum beta2-microglobulin (β2m), HCV status, and presence of cirrhosis, only R-IPI, β2m, and cirrhosis showed independent prognostic impact on OS. The presence of HCV in DLBCL patients entails higher number of complications and early deaths; however, liver impairment and not the hepatitis viral status was the key feature in the outcome of the patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma subtype in Western countries and is characterized by aggressive clinical behavior [1]. CHOP chemotherapy has been the mainstay of therapy for decades, with complete remission (CR) rates of 50% and 5-year overall survival (OS) of 30–40%. The addition of rituximab, an anti-CD20 antibody, significantly improved the outcome in young and elderly patients [2], becoming the standard of care nowadays.

The prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) is around 1.6–2.6% [3]. Many epidemiological studies have associated HCV with the development of some types of lymphomas, including DLCBL [4]. Moreover, different studies have described that DLBCL patients with HCV+ have specific clinico-biological characteristics [5, 6]. In this line, a recent manuscript has shown that NOTCH pathway is more frequently mutated in HCV+ patients [7]. Some studies have revealed that high pre-treatment transaminase levels or HCV viral load are associated with higher incidence of liver toxicity, although with limited impact on OS [8–10]. Despite recent publications, many aspects of the prognostic impact of HCV infection in DLBCL patients, tolerance to chemotherapy, and clinical outcome remain controversial. Thus, the management of patients with DLBCL carrying hepatitis C virus is still a challenge at the clinical setting. The aim of the present study was to analyze the main clinico-biological features and outcome HCV+ patients with DLBCL treated in a single institution in the rituximab era.

Patients and methods

Patients

A total of 321 patients (median age, 66 years; male/female distribution 161/160), diagnosed with DLBCL in a single institution between 2002 and 2013 were included. The only criterion of inclusion was the availability of histological material and hepatitis C serology. We excluded patients with a recognized disease phase of follicular lymphoma or another type of indolent lymphoma with subsequent transformation into a DLBCL, as well as those with immunodeficiency-associated lymphoma, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders, and also those with intravascular, primary central nervous system, primary effusion, or primary mediastinal lymphoma.

At diagnosis, physical examination, blood tests with blood cell counts and serum biochemistry, including β2-microglobulin (β2m) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, CT or PET scan and bone marrow biopsy were performed. Main clinico-biological variables were recorded and analyzed. R-IPI, a revised version of the International Prognosis Index (IPI) for patients treated with immunochemotherapy, was used [11]. All patients received immunochemotherapy unless intolerance or toxicity to rituximab. The standard regimen was the combination of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) every 3 weeks for a total of 6 cycles. Response to therapy, progression-free survival (PFS), and OS were defined by standard criteria [12].

Median follow-up of surviving patients was 4.0 years (range, 0.1–12.2). Median PFS and OS were 4.4 and 10.4 years, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1).

This retrospective study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of Hospital Clinic Barcelona and complied with all of the provisions of the Helsinki Declaration. Informed consent from each participant or each participant’s guardian was obtained.

HCV assessment and liver function determinations

HCV+ patients were considered those with the presence of serum antibodies against HCV. Viral RNA was determined by quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain.

Serum liver function tests were performed at diagnosis and before each cycle of immunochemotherapy. Levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and total bilirubin, were collected for analysis. These three variables were determined using chemoluminescent microparticle immunoassay. The definition and grading of hepatic toxicity were based on the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.0). Liver cirrhosis was diagnosed clinically by ultrasonographical findings suggestive of cirrhosis such as nodular liver surface and splenomegaly (>12 cm), by transient elastography with fibrosis stage F4 (≥14 kPa), or liver biopsy showing a fibrosis score > 4 (METAVIR).

Statistical analysis

The clinical characteristics between groups were compared using a Chi-square method for categorical variables, Student’s t test for continuous variables and non-parametric tests when necessary. Actuarial survival analysis was performed by the Kaplan-Meier method and differences assessed by the log-rank test. To evaluate the prognostic impact of different variables in response to treatment, PFS, and OS, multivariate analyses were performed with the stepwise proportional hazards model (Cox model). All statistical tests were two-sided, and the differences were considered statistically significant at a P value less than 0.05. Statistical analyses were carried out with R-studio v.3.3 and SPSS v.22.

Results

Prevalence of HCV infection and initial characteristics of the patients

Among the 321 included patients, 31 were HCV+ (9.7%). Five of these cases were also anti-HBV core positive (antigen S negative). HCV genotype was known in 10 cases: type 1b, 9; and type 4, 1. Viral RNA load was assessed in 22 HCV+ patients, being detectable in 21 (95%). Five patients had been previously treated for HCV (interferon with or without ribavirin) with no response, while three patients have been treated after CR with interferon-free regimens, attaining a sustained viral response, although with short follow-up. In addition, 11 HCV+ patients had compensated cirrhosis.

Clinico-biological features at the time of DLBCL diagnosis and outcome according to viral status are detailed in Table 1. Compared to cases without hepatitis, HCV+ patients were older (median age 71 vs. 64 years, P = 0.03), had more often B symptoms (P = 0.013), as well as spleen (P = 0.003) and liver (P = 0.011) involvement.

Immunochemotherapy and liver toxicity

The proportion of patients treated with adriamycin-containing regimens was 244 of 260 cases (90%) without hepatitis and 23 of 31 (74%) for HCV+ patients. The main reason to avoid adriamycin was advanced age (≥80 years in 26/38 patients).

As detailed in Table 2, pre-treatment ALT levels were elevated (≥2.5× upper normal limit (UNL)) in 18/284 patients (6%) without hepatitis, whereas HCV+ patients had high levels in 3/30 (10%). Pretreatment serum bilirubin was elevated (≥2 mg/dL) in 13/284 patients (5%) without hepatitis and in 6/29 HCV+ patients (21%, P < .001).

During the treatment period, 34 cases developed liver toxicity grade ≥ 2 (WHO): 22/282 HCV− cases (8%) vs. 12/28 HCV+ (43%) (P < .001). Five patients showed liver decompensation during the treatment period (ascites, three events; upper gastrointestinal bleeding, two events); all cases were HCV+. These five patients met cirrhosis criteria and died within 4 months from diagnosis. Non-hepatic complications (89% infections) were also seen more frequently in HCV+ patients (67% vs. 41%; P = .009). No statistical differences were seen among the groups regarding completion of planned therapy or dose-adjustment of adriamycin. However, HCV+ patients with elevated pretreatment bilirubin less frequently completed the initial planned treatment (25% vs. 80%, P = .059).

Patients who developed liver toxicity had an inferior OS compared to those who did not (5-year OS 48% vs. 63%, P = .014).

Upon completion of immunochemotherapy, 28/313 (9%) patients had high serum transaminases and/or bilirubin, including 17 who developed such toxicity during treatment. Elevation of pre-treatment bilirubin predicted higher incidence of grade ≥2 hepatic toxicity (39 vs. 9%; P = 0.02) and worse OS (5-year OS 62 vs. 40%; P = 0.007).

Response to therapy and outcome

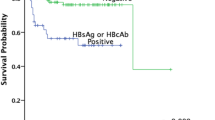

Response to treatment according to the viral status is detailed in Table 1. Five-year PFS for HCV- and HCV+ was 51% (95% CI 45–58) and 33% (95% CI 18–57), respectively (P = .056, Fig. 1a). Variables predicting poor PFS were high serum LDH, β2-microglobulin, low albumin, and high risk R-IPI (P < 0.01 in all cases). One hundred eleven patients died during follow-up.

Early deaths (within 4 months of diagnosis, N = 31) occurred more frequently in HCV+ (26 vs. 8%, P = .005). Causes of early death for HCV+ patients were complications during treatment (8 of 8 cases, including 3 hepatic decompensations), while for HCV- patients causes were progression (9 of 21) and complications during treatment (12 of 21) (P = .003). Causes of death of HCV- patients were toxicity during treatment (n = 22, 23%), lymphoma progression (n = 59, 63%), and late complications (n = 13, 14%). For the HCV+, causes were toxicity during treatment (n = 8, 45%), progression (n = 7, 39%), and late complications (n = 3, 17%) (P = .001). Five-year OS was 63 and 37% for HCV− and HCV+ patients, respectively (P = .001, Fig. 1b). Other variables predicting poor OS were high serum LDH, β2-microglobulin, low albumin, and high risk R-IPI (P < 0.01 in all cases).

Regarding the 31 HCV+ patients, pre-treatment elevated bilirubin was associated with shorter OS (P < .001; Fig. 2a), while the presence of pre-treatment transaminase (ALT or AST) levels above normal did not significantly impact OS. Patients who met cirrhosis criteria showed shorter OS than those who did not (5-year OS 9 vs. 56% (P = .005); Fig. 2b). Of note, 10/11 patients with cirrhosis eventually died, with a median OS of 3.3 months.

A multivariate analysis was performed in order to assess the impact of R-IPI (very good vs. good vs. poor), HCV status (negative vs. positive), β2m (low vs. high), and cirrhosis (absence vs. presence). In the final model with 306 patients, R-IPI (hazard ratio [HR] 2.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.69–7.3; P = .02), high β2m (HR 1.76; 95% CI, 1.16–2.68; P = .008) and presence of cirrhosis (HR 4.66; 95% CI, 2.23–9.76; P < .001) were the only variables with independent impact on OS.

Finally, we applied the recently published score for HCV+ DLBCL patients in our cases [13], showing a 5-year OS of 33, 45, and 17% for patients with low, intermediate, and high risk, respectively (P = .012).

Discussion

In the present series, the prevalence of HCV among DLBCL patients was 9.7%, higher than the prevalence of 1.7% described in the general Spanish population [14]. This is in line with other reports in DLBCL patients [8]. Of note, 90% of HCV+ cases (9 out of 10) had a type 1 genotype, a proportion similar to other series [9, 15].

In our study, HCV+ patients were older, had more often B symptoms, spleen and liver involvement, while PFS was not significantly different from HCV− patients. Five-year OS for HCV+ patients was shorter compared to HCV− cases (37 vs. 63%), but this difference was not confirmed in the multivariate analysis. These findings are in agreement with other series [8–10] and confirm that HCV infection alone is not the most significant risk factor for outcome in DLBCL patients. On the contrary, we observed that the presence of cirrhosis was a key point for shorter OS. In fact, HCV+ patients without cirrhosis had an almost identical outcome as compared to the non-infected patients. In other words, it seems that it is not the presence of HCV infection, but the liver damage that unfavorably impacts on the outcome of DLBCL patients. Thus, treatment decisions should not be based solely on the presence of chronic hepatitis C infection. These results have yet to be confirmed, since some cases lacked the viral load data, and hence, it is not possible to rule out false positive cases or spontaneous remissions.

As expected, pre-treatment levels of bilirubin were elevated more often in HCV+ than in HCV− patients. In agreement with other series, liver toxicity also occurred more often in HCV+ patients, including those with normal pre-treatment values of bilirubin or transaminases [9, 10]. In our series, HCV+ patients with elevated pretreatment bilirubin less frequently completed the initial planned treatment. Therefore, liver function should be carefully monitored before, during and after treatment, and adjust the dose of drugs accordingly to minimize liver damage.

We also observed an increase in the rate of infections in HCV+ cases, especially in the cirrhotic patients. Thus, antibiotic prophylaxis should be considered in these patients with elevated bilirubin or ALT at diagnosis or during therapy. In this sense, it is of note that HCV+ patients had a higher incidence of early death (<4 months), all due to complications during treatment (sepsis and liver decompensation). This phenomenon remarks the higher incidence of toxicity during treatment, especially in cirrhotic patients.

Recently, an HCV prognostic score was proposed for HCV+ DLBCL patients that included viral load, serum albumin, and performance status. In this study, it stratified the outcome of patients better than the IPI score [13]. Of note, this score was based on more than 500 patients, although it has not yet been validated. In our series, patients with high risk (two or three risk factors) had a similar outcome as described (5-year OS of 20%). However, for low and intermediate risk patients, there was no difference in OS, probably due to the low number of cases. As expected, low albumin and poor performance status (ECOG >1) correlated with an inferior outcome, not only in HCV+ patients.

A few studies analyzed the impact of antiviral therapy on the outcome of DLBCL patients, suggesting a benefit in those who receive this treatment [16, 17]. However, for the time being, the role of antiviral therapy in HCV+ associated DLBCL is unclear. Finally, an aspect to take into account in the management of HCV+ patients in the next future is the impact of the new direct-acting interferon-free antiviral treatments. Concomitant therapy for HCV and lymphoma remains to be tested, but it could potentially be an option to improve outcome, especially in those patients with liver damage.

In summary, HCV+ DLBCL patients without liver damage have a similar outcome as those cases without hepatits C, while HCV+ cases with liver damage showed an increased rate of early deaths due to complications during treatment and, as a consequence, an inferior outcome.

References

(1997) A clinical evaluation of the International Lymphoma Study Group classification of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Classification Project. Blood 89:3909–3918.

Coiffier B, Thieblemont C, Van Den Neste E et al (2010) Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5 trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: a study by the Groupe d’Etudes des Lymphomes de l’Adulte. Blood 116:2040–2045

Garcia-Fulgueiras A, Tormo MJ, Rodriguez T et al (1996) Prevalence of hepatitis B and C markers in the south-east of Spain: an unlinked community-based serosurvey of 2, 203 adults. Scand J Infect Dis 28:17–20

de Sanjose S, Benavente Y, Vajdic CM et al (2008) Hepatitis C and non-Hodgkin lymphoma among 4784 cases and 6269 controls from the international lymphoma epidemiology consortium. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 6:451–458

Besson C, Canioni D, Lepage E et al (2006) Characteristics and outcome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in hepatitis C virus-positive patients in LNH 93 and LNH 98 Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte programs. J Clin Oncol 24:953–960

Visco C, Arcaini L, Brusamolino E et al (2006) Distinctive natural history in hepatitis C virus positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: analysis of 156 patients from northern Italy. Ann Oncol 17:1434–1440

Arcaini L, Rossi D, Lucioni M et al (2015) The NOTCH pathway is recurrently mutated in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma associated with hepatitis C virus infection. Haematologica 100:246–252

Nishikawa H, Tsudo M, Osaki Y (2012) Clinical outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with hepatitis C virus infection in the rituximab era: a single center experience. Oncol Rep 28:835–840

Chen TT, Chiu CF, Yang TY et al (2015) Hepatitis C infection is associated with hepatic toxicity but does not compromise the survival of patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma treated with rituximab-based chemotherapy. Leuk Res 39:151–156

Ennishi D, Maeda Y, Niitsu N et al (2010) Hepatic toxicity and prognosis in hepatitis C virus-infected patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab-containing chemotherapy regimens: a Japanese multicenter analysis. Blood 116:5119–5125

Sehn LH, Berry B, Chhanabhai M et al (2007) The revised international prognostic index (R-IPI) is a better predictor of outcome than the standard IPI for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. Blood 109:1857–1861

Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B et al (1999) Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. NCI sponsored international working group. J Clin Oncol 17:1244

Merli M, Visco C, Spina M et al (2014) Outcome prediction of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas associated with hepatitis C virus infection: a study on behalf of the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi. Haematologica 99:489–496

Alonso Lopez S, Agudo Fernandez S, Garcia Del Val A, et al. [Hepatitis C seroprevalence in an at-risk population in the southwest Madrid region of Spain]. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016.

Pellicelli AM, Marignani M, Zoli V et al (2011) Hepatitis C virus-related B cell subtypes in non Hodgkin’s lymphoma. World J Hepatol 3:278–284

Hosry J, Mahale P, Turturro F, et al. (2016) Antiviral therapy improves overall survival in hepatitis C virus-infected patients who develop diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Int J Cancer.

Michot JM, Canioni D, Driss H et al (2015) Antiviral therapy is associated with a better survival in patients with hepatitis C virus and B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas, ANRS HC-13 lympho-C study. Am J Hematol 90:197–203

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spanish Ministry of Health (PI12/01536 and PIE1313/00033); Red Temática de Investigación Cooperativa en Cáncer (RTICC, RD12/0036/0023), all co-founded by the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER); by Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca (AGAUR, 2014 SGR 668), Generalitat de Catalunya, and by the “Josep Font” grant from Hospital Clinic Barcelona.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Ivan Dlouhy and Miguel Á. Torrente equally contributed to this manuscript

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Fig 1

Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) of the overall cohort with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (TIFF 96 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dlouhy, I., Torrente, M.Á., Lens, S. et al. Clinico-biological characteristics and outcome of hepatitis C virus-positive patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy. Ann Hematol 96, 405–410 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-016-2903-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-016-2903-8