Abstract

Arterio-venous fistulas may develop spontaneously, following trauma or infection, or be iatrogenic in nature. We present a rare case of a jejunal arterio- venous fistula in a 35-year-old man with a history of pancreatic head resection that had been performed two years previously because of chronic pancreatitis. The patient was admitted with acute upper abdominal pain, vomiting and an abdominal machinery-type bruit. The diagnosis of a jejunal arterio-venous fistula was established by MR imaging. Transfemoral angiography was performed to assess the possibility of catheter embolization. The angiographic study revealed a small aneurysm of the third jejunal artery, abnormal early filling of dilated jejunal veins and marked filling of the slightly dilated portal vein (13–14 mm). We considered the presence of segmental portal hypertension. The patient was treated with coil embolization in the same angiographic session. This case report demonstrates the importance of auscultation of the abdomen in the initial clinical examination. MR imaging and color Doppler ultrasound are excellent noninvasive tools in establishing the diagnosis. The role of interventional radiological techniques in the treatment of early portal hypertension secondary to jejunal arterio-venous fistula is discussed at a time when this condition is still asymptomatic. A review of the current literature is included.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Visceral arterio-venous (A-V) fistulas constitute a rare diagnosis. Previous reports mostly concentrate on splenic A-V fistulas which represent the most common type of visceral arterio-venous fistula reported in the literature to date [1]. Increases in portal venous flow are associated with small changes in portal venous pressure due to liver compliance, therefore complicating high-flow states are uncommon causes of portal hypertension [2, 3]. In a few patients with an A-V fistula, portal hypertension may develop due to a combination of increased resistance and increased flow within the portal circulation [4,5,6]. These hemodynamic differences may account for the variable patterns of presentation associated with the location of the arterio-venous fistula. Clinically, A-V fistulas located along the jejunal arteries frequently manifest with isolated signs such as bleeding, abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss and a steal phenomenon, suggesting that only a segment of the portal venous system (segmental portal hypertension) is involved [1]. The aim of patient management is treatment of the underlying cause to prevent the development of portal hypertension complications such as variceal hemorrhage and ascites.

Case Report

A 35-year-old male presented with upper abdominal pain and vomiting. Significantly, 2 years ago the patient had an episode of chronic pancreatitis, which was treated surgically by partial pancreatectomy. Since that time he had abstained from alcohol consumption. At the time of admission to the emergency unit he was normotensive and had a normal pulse rate. Abdominal examination demonstrated a nondistended abdomen, soft to palpation and without palpable resistance. Auscultation revealed a machinery-type bruit in the right and left hypochondrium. The leukocyte count of 18.5 × 10*9/1 (3.2–9.0 × 10*9/1) and the serum-amylase value of 596 U/l (63–228 U/l) indicated the presence of an acutely mild pancreatitis.

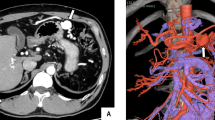

With a suspected clinical diagnosis of mild acute pancreatitis and a visceral arterio-venous fistula, MR-imaging (MRi) was performed on the same day which revealed an A-V fistula arising from the superior mesenteric artery (Fig. 1) and signs of acute exudative pancreatitis. There was no regional hypoperfusion or necrosis within the pancreatic parenchyma.

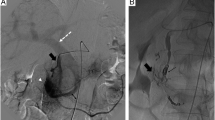

In view of these findings, embolization via the superior mesenteric artery was attempted. The initial abdominal aortic angiogram revealed an A-V fistula arising from the superior mesenteric artery (Fig. 2). Selective arteriography of the superior mesenteric artery was performed with a 5 F Cobra catheter (William Cook AG, Medical Products, DK-4632 Bjaeverskov) in an attempt to localize the feeding artery. The selective angiographic study of the superior mesenteric artery revealed a tortuous course of the third branch of a jejunal artery (Fig. 3), with a terminal aneurysm and a fistulous communication to a dilated jejunal vein, with abnormal early filling of this vein and marked filling of the slightly dilated portal vein.

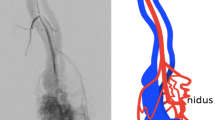

The catheter was subsequently placed superselectively into the origin of the third branch of the jejunal artery, which was shown to divide into a cranial and caudal branch. This was followed by coaxial passage of an infusion microcatheter FAS-Tracker 18 (Boston Scientific Cork Ltd, Medi-Tech Target, Ireland) into the caudal branch of the third jejunal artery. After inserting two 5 mm microcoils (Boston Scientific Cork Ltd, Medi-Tech Target, Ireland) into the caudal branch, one coil was flushed into the dilated jejunal vein and one coil into the right branch of the portal vein. Following the additional insertion of three 7 mm microcoils, angiography showed complete embolization of the caudal branch and revealed that the true feeder was indeed the cranial branch of the third jejunal artery. Subsequently, coil embolization of the cranial branch with three 7 mm diameter coils was performed (Fig. 4).

Following microcoil embolization of the arterio-venous fistula, angiography of the superior mesenteric artery revealed complete occlusion (arrowhead) of the A-V fistula (Fig. 5). Despite displacement of two smaller coils across the dilated jejunal vein into the right portal vein branch, there were no procedural complications and liver function tests remained normal following the embolization.

Discussion

Well-known etiologies of visceral arterio-venous fistulas include trauma, arterial rupture, infection and iatrogenic causes [7,8,9,10]. In contrast to spontaneous aneurysm formation and spontaneous development of an A-V fistula, a traumatic or iatrogenic cause of the fistula, as was present in our case, is easier to explain [11,12,13,14].

An acquired arterio-venous fistula, as that described in our case report, can be the sequel of pancreatitis, but iatrogenic procedures such as suture ligation of an artery and an adjacent vein are much more commonly the cause [10,28]. The etiology of the A-V fistula described in our case report, is certainly more likely to be the result of a previous surgical procedure than the result of perforation of a pseudoaneurysm following vascular degeneration due to pancreatitis. A definite cause, however, cannot be established with certainty in this case.

An iatrogenic jejunal A-V fistula, however, constitutes a rare diagnosis. In the case of portal hypertension secondary to a visceral A-V fistula, closure of this shunt is sufficiently adequate therapy [15,16,17,18,19,20] The clinical presentation and symptoms of patients with visceral A-V fistulas are similar to the symptoms of patients with portal hypertension due to chronic liver disease. The distinguishing and most frequently observed clinical sign in patients with a visceral arterio-venous fistula is a machinery-type bruit (61%) in the abdomen [1, 21]. Our review of the literature revealed that only a few patients with a splenic A-V fistula (16%) had no symptoms or signs of portal hypertension [1, 21, 22].

Traditionally, surgical ligation of the artery supplying the fistula or simple resection of the vascular anomaly has been performed to date. Recently, however, embolization of A-V fistulas has increasingly been performed in place of surgery due to the relatively high peri-operative mortality rate and in view of the rapid development of various new interventional techniques [7, 8, 11, 13, 23]. Steel coils, agents for permanent embolic occlusion and detachable balloons are examples of materials that may be used to treat visceral A-V shunts [15, 19, 24, 25].

The method of choice for embolization of a jejunal arterio-venous fistula is the Tracker-18 infusion catheter using microcoils as embolization material. This 3 F (1 mm) coaxial catheter can be inserted through any angiography catheter that allows passage of a 0.97 mm (0.038-inch) wire. An extremely thin guide wire with a diameter of 0.46 mm (0.018 inches) and a long platinum tip, allows superselective insertion of the catheter into the corresponding arterial branch. The microcatheter is then introduced over the guide wire. Microcoils selected according to the inner diameter of the microcatheter (0.46 mm/0.018 inches) are subsequently used for embolization. The coils, designed for the occlusion of small arterial vessels with a diameter of 3–7 mm, are positioned with the use of a special ultra-thin wire placed through the microcatheter or flushed with saline through the microcatheter.

The angiographic embolization technique described in the presented case should be used to embolize visceral A-V fistulas and to replace the more complex embolization techniques such as detachable microballoons or liquid embolization materials. The advantage of the described technique using a Tracker-18 catheter is the high selectivity with which segmental and terminal branches of visceral A-V fistulas can be embolized. With this technique, mesenteric infarction, one of the potential complications of embolization, can often be avoided.

Careful measurement of the diameter of the feeding artery and of the arterio- venous fistula is important to avoid displacement of coils into draining jejunal veins or into the portal vein. When there is doubt, a larger coil should preferentially be employed. With exact placement of the coils, the risk of segmental mesenteric infarction is extremely low. Displacement of coils into the portal vein normally does not result in a complication, similar to the displacement of coils into the lung [26,27].

The reason that two microcoils passed through the AV fistula and entered the portal venous system can be explained on the following grounds: The diameter of the A-V fistula was underestimated despite utilization of a superselective catheter technique and the coil diameter of 5 mm that was selected proved to be too small. In addition, the tip of the infusion microcatheter was placed immediately proximal to the arterio-venous fistula. As a result of the selected coil diameter and the injection pressure, one coil was flushed through the A-V fistula into the dilated jejunal vein and one coil into the right branch of the portal vein. In response to this complication, the procedure was successfully completed using the larger diameter (7 mm) coils.

In principle, the use of a microcatheter system and microcoils is a safe procedure with a low complication rate for embolization of A-V fistulas, especially when dealing with a vascular region that is anatomically difficult to catheterize, such as that supplied by the mesenteric arteries. In this situation the microcatheter technique is easier to perform using microcoils than using detachable balloons, where as a rule, catheters with a wide lumen are required. Furthermore, by selection of a balloon size that is too small, there is danger that the balloon itself may migrate through the A-V fistula. On the basis of the difficulty of placement, we consider the use of tissue glue to be a complicated and exceptionally hazardous procedure.

Although the migration of a microcoil into the portal venous system does not result in any major complication, it is advisable to resort primarily to a larger coil size in order to prevent possible migration. In this case, however, there is the risk that the coil may stretch out somewhat within the vessel, thus necessitating the use of several coils to occlude the vascular segment. In addition, the fact that small side branches in the segment proximal to the fistula may be occluded must be considered.

In conclusion, management of a jejunal arterio-venous fistula by embolization with microcoils was found to be an effective method of treating this condition in its early stages, especially in avoiding the development of portal hypertension. To our knowledge, no similar reports describing this embolization technique have been published to date.

References

J Vauthey RJ Tomczak T Helmberger P Gertsch C Forsmark J Caridi A Reed MR Langham G Lauwers P Goffette J Lerut (1997) ArticleTitleThe arterioportal fistula syndrome: clinicopathologic features, diagnosis, and therapy 113 1390–1401

TD Boyer (1995) ArticleTitlePortal hypertensive haemorrhage: pathogenesis and risk factors Semin Gastrointest Dis 6 125–133 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:BymD38vgvVM%3D Occurrence Handle7551969

CW Van Way MJ Crane DH Riddel JH Foster (1971) ArticleTitleArteriovenous fistula in the portal circulation Surgery 70 876–890 Occurrence Handle5124667

TD Boyer (1990) Portal hypertension and bleeding oesophageal varices D Zakim TD Boyer (Eds) Hepatology PA Saunders Philadelphia 572–615

JA Schilling FW McKee (1953) ArticleTitleLate follow-up on experimental hepatic-portal arteriovenous fistulae Surg Forum 4 392–397 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:CyuC3cjltFM%3D Occurrence Handle13187306

GD Zuidema WD Gaisford MR Abell TM Brody Sa Neill CG Child (1963) ArticleTitleSegmental portal arterialization of canine liver Surgery 53 689–698 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:CC2C1Mrps1E%3D Occurrence Handle14004067

PL Redmond DA Kumpe (1988) ArticleTitleEmbolisation of an intrahepatic arterioportal fistula: case report and review of the literature Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 11 274–277

PD Orons AB Zajko CA Jungrels (1994) ArticleTitleArterioportal fistula causing portal hypertension and variceal bleeding: treatment with a detachable balloon J Vasc Interv Radiol 5 373–376 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:ByuB2czhvFQ%3D Occurrence Handle8186610

J Bakker SG Robben FW Hazebroek M Meradji (1994) ArticleTitleCongenital arterioportal fistula of the liver with reversal of flow in the superior mesenteric vein Pediatr Radiol 24(3 198–199

DG Metzger (1972) ArticleTitleMesenteric arteriovenous fistula Am J Surg 124 767 Occurrence Handle10.1016/0002-9610(72)90135-3 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:CSyD2cnhvFc%3D Occurrence Handle4539037

R Gartside RL Gamelli (1987) ArticleTitleSplenic arterio-venous fistula J Trauma 27 671–673 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:BiiB2MvivFM%3D Occurrence Handle3599115

TE Gudmundsen M Lie H Ostensen (1988) ArticleTitleSplenic arterio-venous fistula. Case-report Acta Chir Scand 153 1313–1314

D Campbell JG Geragthy MM McNicholas JJ Murphy (1991) ArticleTitleDelayed presentation of traumatic splenic arterio-venous fistula Ir Med J 84 129–130 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:By2B1czmtlA%3D Occurrence Handle1817121

Uflacker Renan, Selby J. Bayne, Chavin Kenneth, Rogers Jeffrey, Baliga Prabhakar (2002) Transcatheter splenic artery occlusion for treatment of splenic artery steal syndrome after orthotopic liver transplantation. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 6:300–306

DL Ridout SP Bralow A Chait M Nusbaum (1989) ArticleTitleHepatoportal fistula treated with detachable balloon embolotherapy Am J Gastroenterol 84 63–66 Occurrence Handle2912033

YN Applbaum JW Renner (1987) ArticleTitleSteel coil embolisation of hepatoportal fistulae Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 10 75–79

P Ramchandani NJ Goldenberg RL Soulen RI White (1983) ArticleTitleIsobutyl 2-cyanoacrylate embolisation of hepatoportal fistula AJR 140 137–140 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:BiyD1MjhsFA%3D Occurrence Handle6600302

GP Aithal BJ Alabdi JDG Rose OFW James M Hudson (1999) ArticleTitlePortal hypertension secondary to arterioportal fistula: two unusual cases Liver 19 343–347 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1Mzosleqsg%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10459634

Takuji Yamagami, Toshiyuki Nakamura, Tsunehiko Nishimura (2000) Portal hypertension secondary to spontaneous arterio-portal fistulas: transcatheter arterial embolisation with n-butyl cyanoacrylate and microcoils. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 23:400–402

Angle FJ, Matsumoto AH, McGraw KJ, Hagspiel KD, Spinosa DJ, McCullough CS (1999) Percutaneous embolisation of a high-flow pancreatic transplant arteriovenous fistula 22(2):147–149

CP Strassburg JS Bleck H Rosenthal (1996) ArticleTitleDiarrhoea, massive ascites, and portal hypertension: rare case of a splenic arterio-venous fistula Z Gastroenterol 34 243–244 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:BymA3c%2FmsFA%3D Occurrence Handle8686353

Charles EK (2002) Portal hypertension: collaborative hypertext of Radiology Medical College of Wisconsin

BJ Phillips AJ Fabrega (2000) ArticleTitleEmbolisation of a mesenteric arteriovenous fistula following pancreatic allograft: the steal effect Transplantation 70(10 1529–1531 Occurrence Handle10.1097/00007890-200011270-00022

Toshiya Shibata, Tadashi Sagoh, Fumie Ametani, Yoji Maetani, Kyo Itoh, Junji Konishi (2002) Transcatheter microcoil embolotherapy for ruptured pseudoaneurysm following pancreatic and biliary surgery. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 25(3):180–185

L Defreyne I De Schrijver P Vanlangenhove M Kunnen (2002) ArticleTitleDetachable balloon embolisation of an aneurysmal gastroduodenal arterioportal fistula Eur Radiol 12(1 231–236 Occurrence Handle10.1007/s003300100935

RW Prokesch AA Bankier A Ba-Ssalamah W Schima TR Bader J Lammer (2001) ArticleTitleDisplacement of coils into the lung during embolotherapy: clinical importance and follow-up with helical CT Acad Radiol 8(6 501–508 Occurrence Handle10.1016/S1076-6332(03)80622-0

OF Hennessy RN Gibson DJ Allison (1986) ArticleTitleUse of giant steel coils in the therapeutic embolisation of a superior mesenteric artery-portal vein fistula CVIR 9 42–45 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:BimB3Mjps1Y%3D

Peer A, Slutzki S, Witz E, Abrahmsohn R, Bogokowsky H, Leonov Y (1989) Transcatheter occlusion of inferior mesenteric arteriovenous fistula: a case report. 12:35–37

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Fax 0041 31 6324874

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sonnenschein, M., Anderson, S., Lourens, S. et al. A Rare Case of Jejunal Arterio-Venous Fistula: Treatment with Superselective Catheter Embolization with a Tracker-18 Catheter and Microcoils. CVIR 27, 671–674 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-004-0101-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-004-0101-x