Abstract

Introduction

Complicated diaphragmatic hernia (DH) can be congenital or acquired. Congenital diaphragmatic hernias (CDH) are rare and often can be asymptomatic until adulthood. Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia (TDH) is a complication that occurs in about 1–5% of victims of road accidents and in 10–15% of penetrating traumas of the lower chest. CDH and TDH are potentially life-threatening conditions, and the management in emergency setting still debated. This study aims to evaluate the surgical treatment options in emergency setting.

Methods

A bibliographic research reporting the item “emergency surgery” linked with “traumatic diaphragmatic rupture” and “congenital diaphragmatic hernia” was performed. Several parameters were recorded including sex, age, etiology, diagnosis, treatment, site and herniated organs.

Results

The research included 146 articles, and 1542 patients were analyzed. Most of the complicated diaphragmatic hernias occurred for a diaphragmatic defect due to trauma, only 7.2% occurred for a congenital diaphragmatic defect. The main diagnostic method used was chest X-ray and CT scan. Laparotomic approach still remains predominant compared to the minimally invasive approach.

Conclusion

Surgery is the treatment of choice and is strongly influenced by the preoperative setting, performed mainly with X-ray and CT scan. Minimally invasive approach is safe and feasible but is highly dependent on the surgeon's expertise, especially in emergency setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Diaphragmatic hernia (DH) is a defect of the diaphragm which allows the passage of an organ, or part of it, into the thoracic cavity. DH can be congenital or acquired. Congenital diaphragmatic hernias (CDH) are rare. CDH prevalence ranges from 1.7 to 5.7 per 10,000 births [1] with a survival rate of 67% [2]. Normally, during the eighth week of gestation, the diaphragm formation divides the thoracic cavity from the peritoneal one. The premature bowel returns to the abdomen or the incomplete development of the diaphragm are the etiopathological factors of CDH [3]. Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia (TDH) occurs in about 1–5% of victims of road accidents and in 10–15% of penetrating traumas of the lower chest [4].

Complicated DH is a rare problem encountered by Emergency Department. The diagnosis and management of complicated DH can be a medical issue; the onset of symptoms is subsequent to the traumatic event. Often the symptoms may occur even months or years after the injury [5].

There is no consensus about the indications to surgery and the timing. This study aims to evaluate the surgical treatment options in emergency setting.

Methods

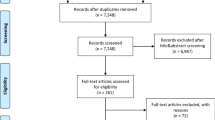

An extensive bibliographic research of literature according to PRISMA criteria was performed (Fig. 1). Medline and PubMed were consulted in order to identify articles reporting the item “emergency surgery” from 1983 up to May 2020, and then, it has been meshed using the Boolean operator “AND” and “OR” with the following mesh terms: “traumatic diaphragmatic rupture” and “congenital diaphragmatic hernia.” Additional articles were searched by manual identification from the key articles.

Inclusion criteria articles in English language, reporting “emergency surgery” for diaphragmatic hernia (congenital and traumatic). In case of multiple papers from the same group of authors, an effort was made to identify duplicate paper.

Exclusion criteria non-English papers, patients under 19 years, hiatal or paraesophageal hernias, procedures performed in “elective setting” have been excluded.

Several parameters were recorded and analyzed including: sex, mean age, etiology, diagnosis (chest X-ray, CT scan, barium studies, MRI and others), treatment (laparoscopic, laparotomic, thoracoscopic, thoracotomic, thoracoabdominal, robotic, damage control surgery), use of mesh, site (right or left) and herniated organs.

Results

In the present review, 146 articles were included (Fig. 1, Table 1).

Among the 1542 analyzed patients, 809 (52.4%) were male and 379 (24.5%) were female. In the remaining 354 (22.9%), sex was not specified. The average age was 47.7 (SD ± 18.3) years. Considering the etiology, the cause of hospitalization was trauma in 1261 patients (81.7%) and CDH in 113 (7.2%). Among these, 50 (3.2%) were Bochdalek's hernias (BH) and 54 (3.5%) were Morgagni's hernias (MH). Five patients had previously performed surgery, 5 were pregnant, and in 151 patients the etiological diagnosis was not reported.

Trauma patients were younger than patients who developed symptoms for a congenital diaphragmatic defect (45.1 vs. 53.1 years). Mean age of Bochdalek’s hernia patients was 47.2 ± 18.3 years while in patients with Morgagni’s hernia was 64.1 ± 19.2 years.

In 709 cases (45.9%), the defect was located on the left side of the diaphragm while in 273 cases (17.7%) on the right one. In only 10 cases (all traumas), the defect was bilateral, and in 550 patients the site of the herniation was not specified (Table 2). The left hemidiaphragm was more involved than the right one: trauma (644 vs. 207), Bochdalek (34 vs. 14), post-surgery DH (4 vs. 1), during pregnancy DH (4 vs. 1). Unlike the others, Morgagni’s hernias mainly occur on the right side compared to the left side (45 vs. 9) (Table 3).

Chest X-ray was the most common diagnostic test used in 697 patients (45.2%). CT scan also plays a major role in instrumental diagnostic methods and was used in 315 cases (20.4%). In our analysis, the other methods were much less used: barium studies in 15 cases, US in 15, gastrografin swallow in 5, MRI in 8, EGDS in 5 and manometry in only 1 case. Diagnosis was achieved intraoperatively 6 performed. Diagnostic tests were not performed in 12 patients because they were unstable. Diagnostic methods could not be deduced in 463 patients. Of the 1261 trauma patients, a delayed presentation (> 7 days) has been reported in 297 cases. Surgery was performed the same day of hospital admission in 47 trauma patients (interval time range: 1 to 9 h). Surgery was performed in the first week after trauma in 100 cases. Data about time interval from trauma to surgery have not been reported in 817 patients.

As far as surgical treatment is concerned, the open approach is the one widely used. Laparotomy, thoracotomy and thoracoabdominal approach were used in 907 cases (58.8%), 184 (11.9%) and 42 (2.7%) patients, respectively. Laparoscopic, thoracoscopic and robotic approaches were used in 103 (6.6%), 28 (1.8%) and 3 (0.1%) patients, respectively. A conservative management was chosen in 11 patients for contraindications to surgery or because they were unstable. In 22 patients, along with the repair of the diaphragmatic defect, another associated procedure was performed (mainly splenectomy, gastrectomy and colectomy). Damage control surgery (DCS) was performed in only 12 patients. In one patient, a colopexy was performed to cover, without repairing, a massive diaphragmatic defect.

The use of meshes has been observed only in 55 cases, 17 times with laparotomic approach and 35 times with laparoscopy.

The treatment for each category of diaphragmatic hernias is summarized in Table 4.

The stomach was the most common herniated organ in 176 cases, followed by the colon, in 125 cases, the omentum (90 cases), the small bowel (95 cases) and the spleen (44 cases). Liver and kidney involvement were observed in 32 and 5 patients, respectively. In 68 cases, there was no finding of abdominal organs in the chest, while for 906 patients, this information was not reported.

Discussion

The symptomatology of complicated diaphragmatic hernias can vary greatly depending also on their etiology. In CDH, the symptoms can be varied and occur at different times. Symptomatic CDH in the childhood derives from pulmonary hypoplasia because the herniation of the organs in the chest during prenatal period prevents the development of the lungs [6]. In spite of our series does not suggest it clearly, literature reports BH as the most frequent among the CDH [7, 8]. The MH are rarer. MH have an anterior development and derive from a closure defect of the sternal part of the diaphragm with the seventh chondrocostal arch. They can remain asymptomatic, and often, the diagnosis is an incidental finding during other instrumental test (chest X-ray) [9, 10]. CDH in the adulthood can present with non-specific respiratory and gastrointestinal disorders. Gastrointestinal problems at the diagnosis can be more common in the left-sided hernias, where the absence of the liver allows the migration of the abdominal organs into the thorax, sometimes causing mild (dyspepsia, recurrent or non-specific abdominal pain) or acute (obstructions or flies) abdominal symptoms. In right-side CDH, respiratory symptoms are predominant [11, 12]. TDH presentation symptoms may vary depending on the type of trauma (blunt or penetrating), on the amount of energy absorbed by the body and on the involved side. The most common cause of TDH is a traumatic event that creates an increase gradient between the abdominal and thoracic compartment with a rupture mainly at the level of the embryonic melting points. Penetrating traumas are the most frequent, but the diaphragmatic defects are generally smaller than the blunt ones [13]. Small chronic traumatic events such as coughing or obesity acting over time may cause the exhaustion of already existing hiatuses or the rupture of weaknesses. In fact, in some cases the symptoms may not be present for many months or years after the trauma [5]. Pregnancy also plays a fundamental role in this context; increased abdominal pressure that occurs in this period contributes to the rupture of the diaphragm in its weaknesses point or can unmask congenital diaphragmatic defects. It is a rare situation, and in our series, it occurred in 5 cases (0,5%), but in some cases, it may endanger the life of the fetus; therefore, it must not be ignored [14,15,16,17].

CDH have a different rupture site’s prevalence depending on the type of considered hernia. BH occur more frequently on the left side (80%), [18] MH mainly develop on the right side, but sometimes it can be bilateral or develops on the left side [3]. Our analysis also follows the literature, indeed 68% of BH developed on the left side (34 vs. 14), while almost all MH are on the right one (83%, 45/54). Considering TDH, in our series as well as in literature, the left hemidiaphragm is more commonly involved in blunt or penetrating injuries. This is probably due to the protective effect of the liver for the right hemidiaphragm on the blunt trauma, and the fact that most people use their right hand on the penetrating trauma [19]. The great variability in the etiology of trauma also determines the possibility the defect develops in both hemidiaphragms; in our review, there are only 6 bilateral herniations and all have traumatic origin [20,21,22].

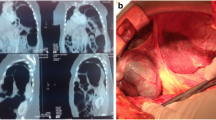

In a “border” pathology between the thorax and the abdomen, a correct preoperative diagnostic work-up is essential. A precise diagnosis inevitably influences the surgeon in choosing the most correct approach to the patient with complicated diaphragmatic hernia. The most used diagnostic test in both our series and literature is chest X-ray. It allows to show an opaque hemithorax with deviation of the mediastinum and when the nature of the thoracic contents is uncertain, nasogastric tube’s course can help in the diagnosis. Soft opacity in the thorax with or without gas can be a sign of hernial sac, and in larger hernias, loops of bowel or the transverse, can also be visualized in the chest [3]. CT scan, with a sensitivity and specificity of 14–82% and 87%, respectively, is considered the diagnostic gold standard [23, 24]. Unlike chest X-ray, which can be normal in case of intermittent herniation, CT scan determines the presence, location and size of the diaphragmatic defect. CT scan can evaluate the intrathoracic herniation of abdominal contents and related complications [25]. Even in one case, in our unit the diagnostic accuracy of CT scan was fundamental to recognize some ischemia signs, such as the forward displacement of the gastric bubble, the missing of the gastric folds and the absence of gastric walls contrast enhancement (Fig. 2). The other diagnostic tests, barium studies, gastrografin swallow, EGDS, US and manometry are much less used in the considered articles. Barium studies can help in revealing barium filling stomach or bowels within the thorax with the strict segment of intestine at hernia site of the diaphragm, while MRI, not performable in emergency, may be used in selected patients (pregnant) [17, 26] in the study of the herniated structures and associated abdominal organ’s injuries [3].

Although there is no consensus on the indications and timing of surgery. Surgery seems to be the treatment of choice for complicated diaphragmatic hernia, both congenital and traumatic. Hernias, especially congenital and accidentally diagnosed, should be corrected even if the patient is asymptomatic because the risk of strangulation or incarceration [10, 27]. In case of complications, surgery is mandatory [23]. Smaller diaphragmatic defects can be primarily closed with a non-absorbable suture [28, 29] while for larger defects, where the primary suture would develop excessive tension due to the considerable loss of tissue, or also in order to reinforce the suture, meshes should be used [30, 31]. The biologic mesh represents an alternative to the synthetic one due to its lower rate of hernia recurrence, higher resistance to infections and lower risk of displacement [23, 32, 33]. The surgical approach can be either thoracotomic or laparotomic depending on the diagnostic investigation’s result and on the surgeon's preferences and skills. The thoracotomic approach, with the addition of a separate laparotomy when indicated, can be recommended especially in chronic herniation in order to reduce visceral-pleural adhesions and to avoid intra-thoracic visceral perforation [34]. Sometimes, thoracoabdominal approach may be necessary in emergency setting, when it is difficult to identify visceral abdominal lesions or to exclude bilaterality [35,36,37].

Recently, laparoscopic or thoracoscopic approach is becoming more feasible and safer allowing a lower hospital length stay and a lower morbidity rate [31, 38,39,40]. Despite this, our analysis reveals that open approaches are still predominant. This could be related to the majority of trauma hernias in which the laparoscopic approach is still very limited. A differentiated analysis of the etiology shows that most of the minimally invasive approaches have been used in repair of complicated CDH, while almost all of the complicated TDH have been approached with laparotomy. A further and even more recent approach is the robotic one, which allows a detailed anatomical visualization and a more precise dissection, but literature findings are poor. In our series, the robotic approach has been used only in 3 patients, [41, 42] and this can be determined by the high costs and the nature of the pathology that often occurs in “emergency setting” compared to “elective setting.” Damage control surgery (DCS) can be an advantageous/rescue alternative in emergency management of the patient with complicated DH although there is no general consensus on its use mainly due to the intra-abdominal hypertension and the abdominal compartment syndrome that may result [43]. DCS can be useful especially in complicated TDH. In unstable patients or damaged/bleeding organs, a second look may be required. The re-exploration of the abdomen 24/48 h later can help surgeon in recognizing the vital/non-vital areas of an ischemic organ leading him in resection [44].

Conclusion

Complicated CDH and TDH have different etiology but similar management. Surgery is the treatment of choice and is strongly influenced by the preoperative setting, performed mainly with chest X-ray and CT scan. DCS can be considered especially in traumas and can offer an advantage in management of the compromised patients. Minimally invasive approach is safe and feasible and offers advantages in terms of hospitalization and lower morbidity rate but is highly dependent on the surgeon's expertise, especially in emergency setting.

Abbreviations

- DH:

-

Diaphragmatic hernia

- CDH:

-

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia

- ADH:

-

Acquired diaphragmatic hernia

- MH:

-

Morgagni’s hernia

- TDH:

-

Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia

References

Garne E, Haeusler M, Barisic I, Gjergja R, Stoll C, Clementi M (2002) Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: evaluation of prenatal diagnosis in 20 European regions. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 19(4):329–333

Baerg J, Kanthimathinathan V, Gollin G (2012) Late-presenting congenital diaphragmatic hernia: diagnostic pitfalls and outcome. Hernia 16(4):461–466

Eren S, Ciris F (2005) Diaphragmatic hernia: diagnostic approaches with review of the literature. Eur J Radiol 54(3):448–459

Meyers BF, McCabe CJ (1993) Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Occult marker of serious injury. Ann Surg 218(6):783–790

Lerner CA, Dang H, Kutilek RA (1997) Strangulated traumatic diaphragmatic hernia simulating a subphrenic abscess. J Emerg Med 15(6):849–853

Hosgor M, Karaca I, Karkiner A et al (2004) Associated malformations in delayed presentation of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg 39(7):1073–1076

Harrison MR, de Lorimier AA (1981) Congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Surg Clin North Am 61(5):1023–1035

Torfs CP, Curry CJ, Bateson TF, Honore LH (1992) A population-based study of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Teratology 46(6):555–565

Kimmelstiel FM, Holgersen LO, Hilfer C (1987) Retrosternal (Morgagni) hernia with small bowel obstruction secondary to a Richter's incarceration. J Pediatr Surg 22(11):998–1000

Nguyen T, Eubanks PJ, Nguyen D, Klein SR (1998) The laparoscopic approach for repair of Morgagni hernias. JSLS 2(1):85–88

Kitano Y, Lally KP, Lally PA (2005) Late-presenting congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg 40(12):1839–1843

Cullen ML, Klein MD, Philippart AI (1985) Congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Surg Clin North Am 65(5):1115–1138

Lu J, Wang B, Che X et al (2016) Delayed traumatic diaphragmatic hernia: a case-series report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 95(32):e4362

Sano A, Kato H, Hamatani H et al (2008) Diaphragmatic hernia with ischemic bowel obstruction in pregnancy: report of a case. Surg Today 38(9):836–840

Eglinton T, Coulter GN, Bagshaw P, Cross L (2006) Diaphragmatic hernias complicating pregnancy. ANZ J Surg 76(7):553–557

Luu TD, Reddy VS, Miller DL, Force SD (2006) Gastric rupture associated with diaphragmatic hernia during pregnancy. Ann Thorac Surg 82(5):1908–1910

Genc MR, Clancy TE, Ferzoco SJ, Norwitz E (2003) Maternal congenital diaphragmatic hernia complicating pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 102(5 Pt 2):1194–1196

Brown SR, Horton JD, Trivette E, Hofmann LJ, Johnson JM (2011) Bochdalek hernia in the adult: demographics, presentation, and surgical management. Hernia 15(1):23–30

Lomoschitz FM, Eisenhuber E, Linnau KF, Peloschek P, Schoder M, Bankier AA (2003) Imaging of chest trauma: radiological patterns of injury and diagnostic algorithms. Eur J Radiol 48(1):61–70

Bergeron E, Clas D, Ratte S et al (2002) Impact of deferred treatment of blunt diaphragmatic rupture: a 15-year experience in six trauma centers in Quebec. J Trauma 52(4):633–640

Zantut LF, Machado MA, Volpe P, Poggetti RS, Birolini D (1993) Bilateral diaphragmatic injury diagnosed by laparoscopy. Rev Paul Med 111(3):430–432

Brown GL, Richardson JD (1985) Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia: a continuing challenge. Ann Thorac Surg 39(2):170–173

Testini M, Girardi A, Isernia RM et al (2017) Emergency surgery due to diaphragmatic hernia: case series and review. World J Emerg Surg 12:23

Kurniawan N, Verheyen L, Ceulemans J (2012) Acute chest pain while exercising: a case report of Bochdalek hernia in an adolescent. Acta Chir Belg 113(4):290–292

Magu S, Agarwal S, Singla S (2012) Computed tomography in the evaluation of diaphragmatic hernia following blunt trauma. Indian J Surg 74(4):288–293

Ngai I, Sheen JJ, Govindappagari S, Garry DJ (2012) Bochdalek hernia in pregnancy. BMJ Case Rep. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2012-006859

Grillo IA, Jastaniah SA, Bayoumi AH et al (2000) Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia: an Asir region (Saudi Arabia) experience. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 42(1):9–14

Okyere I, Okyere P, Glover P (2019) Traumatic right diaphragmatic rupture with hepatothorax in Ghana: two rare cases. Pan Afri Med J 33:256. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2019.33.256.17061

Mittal A, Pardasani M, Baral S, Thakur S (2018) A rare case report of Morgagni hernia with organo-axial gastric volvulus and concomitant para-esophageal hernia, repaired laparoscopically in a septuagenarian. Int J Surg Case Rep 45:45–50

Choy KT, Chiam HC (2019) Dyspnoea and constipation: rare case of large bowel obstruction secondary to an incarcerated Morgagni hernia. BMJ Case Rep 12(6):e229507

Mohamed M, Al-Hillan A, Shah J, Zurkovsky E, Asif A, Hossain M (2020) Symptomatic congenital Morgagni hernia presenting as a chest pain: a case report. J Med Case Rep 14(1):13

Antoniou SA, Pointner R, Granderath FA, Köckerling F (2015) The use of biological meshes in diaphragmatic defects—an evidence-based review of the literature. Front Surg 2:56

Coccolini F, Agresta F, Bassi A et al (2012) Italian biological prosthesis work-group (IBPWG): proposal for a decisional model in using biological prosthesis. World J Emerg Surg 7(1):34

Mansour KA (1997) Trauma to the diaphragm. Chest Surg Clin North Am 7(2):373–383

Nursal TZ, Ugurlu M, Kologlu M, Hamaloglu E (2001) Traumatic diaphragmatic hernias: a report of 26 cases. Hernia 5(1):25–29

Massloom HS (2016) Acute bowel obstruction in a giant recurrent right Bochdalek's hernia: a report of complication on both sides of the diaphragm. North Am J Med Sci 8:252–255

Barbetakis N, Efstathiou A, Vassiliadis M, Xenikakis T, Fessatidis I (2006) Bochdaleck's hernia complicating pregnancy: case report. World J Gastroenterol 12(15):2469–2471

Rehman A, Maliyakkal AM, Naushad VA, Allam H, Suliman AM (2018) A lady with severe abdominal pain following a zumba dance session: a rare presentation of Bochdalek hernia. Cureus 10(4):e2427

Horton JD, Hofmann LJ, Hetz SP (2008) Presentation and management of Morgagni hernias in adults: a review of 298 cases. Surg Endosc 22(6):1413–1420

Susmallian S, Raziel A (2017) A rare case of Bochdalek hernia with concomitant para-esophageal hernia, repaired laparoscopically in an octogenarian. Am J Case Rep 18:1261–1265

Jambhekar A, Robinson S, Housman B, Nguyen J, Gu K, Nakhamiyayev V (2018) Robotic repair of a right-sided Bochdalek hernia: a case report and literature review. J Robot Surg 12(2):351–355

Hunter LM, Mozer AB, Anciano CJ, Oliver AL, Iannettoni MD, Speicher JE (2019) Robotic-assisted thoracoscopic repair of right-sided Bochdalek hernia in adults: a two-case series. Innovations (Phila) 14(1):69–74

Coccolini F, Biffl W, Catena F et al (2015) The open abdomen, indications, management and definitive closure. World J Emerg Surg 10:32

He S, Sade I, Lombardo G, Prabhakaran K (2017) Acute presentation of congenital diaphragmatic hernia requiring damage control laparotomy in an adult patient. J Surg Case Rep 2017(7):rjx144. https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjx144

Coolidge AM, Czerniach D, Wiener DC (2019) Intestinal tamponade. Ann Thorac Surg 108(3):e193–e194

Costa Almeida C, Caroco TV, Nogueira O, Infuli A (2019) Laparoscopic repair of a Morgagni hernia with extra-abdominal transfascial sutures. BMJ Case Rep 12(1):e227600. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2018-227600

Porojan VA, David OI, Coman IS et al (2019) Traumatic diaphragmatic lesions—considerations over a series of 15 consecutive cases. Chirurgia (Bucur) 114(1):73–82

Zanotti D, Fiorani C, Botha A (2019) Beyond belsey: complex laparoscopic hiatus and diaphragmatic hernia repair. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 101(3):162–167

Zhao L, Han Z, Liu H, Zhang Z, Li S (2019) Delayed traumatic diaphragmatic rupture: diagnosis and surgical treatment. J Thorac Dis 11(7):2774–2777

Al-Thani H, Jabbour G, El-Menyar A, Abdelrahman H, Peralta R, Zarour A (2018) Descriptive analysis of right and left-sided traumatic diaphragmatic injuries; case series from a single institution. Bull Emerg Trauma 6(1):16–25

Arikan S, Dogan MB, Kocakusak A et al (2018) Morgagni's hernia: analysis of 21 patients with our clinical experience in diagnosis and treatment. Indian J Surg 80(3):239–244

Gao R, Jia D, Zhao H, WeiWei Z, Yangming WF (2018) A diaphragmatic hernia and pericardial rupture caused by blunt injury of the chest: a case review. J Trauma Nurs 25(5):323–326

Gurrado A, Isernia RM, De Luca A et al (2018) Congenital diaphragmatic disease: an unusual presentation in adulthood. Case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 48:34–37

Tarcoveanu E, Georgescu S, Vasilescu A et al (2018) Laparoscopic management in Morgagni hernia—short series and review of literature. Chirurgia (Bucur) 113(4):551–557

Tonini V, Gozzi G, Cervellera M (2018) Acute pancreatitis due to a Bochdalek hernia in an adult patient. BMJ Case Rep 2018:bcr2017223852. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2017-223852

Ayane GN, Walsh M, Shifa J, Khutsafalo K (2017) Right congenital diaphragmatic hernia associated with abnormality of the liver in adult. Pan Afr Med J 28:70

Manson HJ, Goh YM, Goldsmith P, Scott P, Turner P (2017) Congenital diaphragmatic hernia causing cardiac arrest in a 30-year-old woman. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 99(2):e75–e77

Abdullah M, Stonelake P (2016) Tension pneumothorax due to perforated colon. BMJ Case Rep 2016:bcr2016215325. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2016-215325

Bhatt NR, McMonagle M (2016) Recurrence in a laparoscopically repaired traumatic diaphragmatic hernia: case report and literature review. Trauma Mon 21(1):e20421

De la Cour CD, Teklay B (2016) Acute post-partum presentation of Bochdalek hernia in a grown-up woman. Ugeskr Laeger. 178(44)

Harada M, Tsujimoto H, Nagata K et al (2016) Successful laparoscopic repair of an incarcerated Bochdalek hernia associated with increased intra-abdominal pressure during use of blow gun: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 23:131–133

Kumar A, Bhandari RS (2016) Morgagni hernia presenting as gastric outlet obstruction in an elderly male. J Surg Case Rep 2016(7):rjw126. https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjw126

Manipadam JM, Sebastian GM, Ambady V, Hariharan R (2016) Perforated gastric gangrene without pneumothorax in an adult Bochdalek hernia due to volvulus. J Clin Diagn Res 10(4):Pd09-10

Razi K, Light D, Horgan L (2016) Emergency repair of Morgagni hernia with partial gastric volvulus: our approach. J Surg Case Rep. 2016(8)

Siow SL, Wong CM, Hardin M, Sohail M (2016) Successful laparoscopic management of combined traumatic diaphragmatic rupture and abdominal wall hernia: a case report. J Med Case Rep 10:11

Atef M, Emna T (2015) Bochdalek hernia with gastric volvulus in an adult: common symptoms for an original diagnosis. Medicine (Baltimore) 94(51):e2197

Haratake N, Yamazaki K, Shikada Y (2015) Diaphragmatic hernia caused by heterotopic endometriosis in Chilaiditi syndrome: report of a case. Surg Today 45(9):1194–1196

Sutedja B, Muliani Y (2015) Laparoscopic repair of a Bochdalek hernia in an adult woman. Asian J Endosc Surg 8(3):354–356

Tokur M, Demiroz SM, Sayan M (2015) Non-traumatic tension gastrothorax in a young lady. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 21(4):306–308

Debergh I, Fierens K (2014) Laparoscopic repair of a Bochdalek hernia with incarcerated bowel during pregnancy: report of a case. Surg Today 44(4):753–756

Gali BM, Bakari AA, Wadinga DW, Nganjiwa US (2014) Missed diagnosis of a delayed diaphragmatic hernia as intestinal obstruction: a case report. Niger J Med 23(1):83–85

Moussa G, Thomson PM, Bohra A (2014) Volvulus of the liver with intrathoracic herniation. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 96(7):e27–29

Nakamura T, Masuda K, Thethi RS et al (2014) Successful surgical rescue of delayed onset diaphragmatic hernia following radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 20(4):295–299

Newman MJ (2014) A mistaken case of tension pneumothorax. BMJ Case Rep 2014:bcr2013203435. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2013-203435

Ota H, Kawai H, Matsuo T (2014) Video-assisted minithoracotomy for blunt diaphragmatic rupture presenting as a delayed hemothorax. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 20:911–914

Topuz M, Ozek MC (2014) Right ventricle collapse secondary to hepatothorax caused by diaphragm rupture due to blunt trauma. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 20(6):463–465

Tyagi S, Steele J, Patton B, Fukuhara S, Cooperman A, Wayne M (2014) Laparoscopic repair of an intrapericardial diaphragmatic hernia. Ann Thorac Surg 97(1):332–333

Wigley J, Noble F, King A (2014) Thoracoabdominal herniation-but not as you know it. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 96(5):e1–2

Elangovan A, Chacko J, Gadiyaram S, Moorthy R, Ranjan P (2013) Traumatic tension gastrothorax and pneumothorax. J Emerg Med 44(2):e279–280

Husain M, Hajini FF, Ganguly P, Bukhari S (2013) Laparoscopic repair of adult Bochdalek's hernia. BMJ Case Rep 2013:bcr013009131. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2013-009131

Patle NM, Tantia O, Prasad P, Das PC, Khanna S (2013) Laparoscopic repair of right sided Bochdalek hernia—a case report. Indian J Surg 75(Suppl 1):303–304

Safdar G, Slater R, Garner JP (2013) Laparoscopically assisted repair of an acute traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. BMJ Case Rep 2013:bcr013009415. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2013-009415

Sonthalia N, Ray S, Khanra D et al (2013) Gastric volvulus through Morgagni hernia: an easily overlooked emergency. J Emerg Med 44(6):1092–1096

Vega MT, Maldonado RH, Vega GT, Vega AT, Lievano EA, Velazquez PM (2013) Late-onset congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 4(11):952–954

John PH, Thanakumar J, Krishnan A (2012) Reduced port laparoscopic repair of Bochdalek hernia in an adult: a first report. J Minim Access Surg 8:158–160

Hyngstrom JR, Hu CY, Xing Y et al (2012) Clinicopathology and outcomes for mucinous and signet ring colorectal adenocarcinoma: analysis from the national cancer data base. Ann Surg Oncol 19(9):2814–2821

Nayak HK, Maurya G, Kapoor N, Kar P (2012) Delayed presentation of congenital diaphragmatic hernia presenting with intrathoracic gastric volvulus: a case report and review. BMJ Case Rep 2012:bcr012007332. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2012-007332

Toydemir T, Akinci H, Tekinel M, Suleyman E, Acunas B, Yerdel MA (2012) Laparoscopic repair of an incarcerated bochdalek hernia in an elderly man. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 67(2):199–201

Vassileva CM, Shabosky J, Boley T, Hazelrigg S (2012) Morgagni hernia presenting as a right middle lobe compression. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 18(1):79–81

Vernadakis S, Paul A, Kykalos S, Fouzas I, Kaiser GM, Sotiropoulos GC (2012) Incarcerated diaphragmatic hernia after right hepatectomy for living donor liver transplantation: case report of an extremely rare late donor complication. Transpl Proc 44(9):2770–2772

Agrafiotis AC, Kotzampassakis N, Boudaka W (2011) Complicated right-sided Bochdalek hernia in an adult. Acta Chir Belg 111(3):171–173

Baloyiannis I, Kouritas VK, Karagiannis K, Spyridakis M, Efthimiou M (2011) Isolated right diaphragmatic rupture following blunt trauma. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 59(11):760–762

Okan I, Bas G, Ziyade S et al (2011) Delayed presentation of posttraumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 17(5):435–439

Altinkaya N, Parlakgumus A, Koc Z, Ulusan S (2010) Morgagni hernia: diagnosis with multidetector computed tomography and treatment. Hernia 14(3):277–281

Andreev AL, Protsenko AV, Globin AV (2010) Laparoscopic repair of a posttraumatic left-sided diaphragmatic hernia complicated by strangulation and colon obstruction. JSLS 14(3):410–413

Dente M, Bagarani M (2010) Laparoscopic dual mesh repair of a diaphragmatic hernia of Bochdalek in a symptomatic elderly patient. Updates Surg 62(2):125–128

Hamid KS, Rai SS, Rodriguez JA (2010) Symptomatic Bochdalek hernia in an adult. JSLS 14(2):279–281

Walchalk LR, Stanfield SC (2010) Delayed presentation of traumatic diaphragmatic rupture. J Emerg Med 39(1):21–24

Akhtar K, Qurashi K, Rizvi A, Isla R (2009) Emergency laparoscopic repair of an obstructed Bochdalek hernia in an adult. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 70(12):718–719

Fraser JD, Craft RO, Harold KL, Jaroszewski DE (2009) Minimally invasive repair of a congenital right-sided diaphragmatic hernia in an adult. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 19(1):e5–7

Kavanagh DO, Ryan RS, Waldron R (2008) Acute dyspnoea due to an incarcerated right-sided Bochdalek's hernia. Acta Chir Belg 108(5):604–606

Laaksonen E, Silvasti S, Hakala T (2009) Right-sided Bochdalek hernia in an adult: a case report. J Med Case Rep 3:9291

Ouazzani A, Guerin E, Capelluto E et al (2009) A laparoscopic approach to left diaphragmatic rupture after blunt trauma. Acta Chir Belg 109(2):228–231

Ozpolat B, Dogan OV, Yucel E (2009) Delayed diaphragmatic hernia: an unusual complication of tube thoracostomy. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 15(6):617–618

Peer SM, Devaraddeppa PM, Buggi S (2009) Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia-our experience. Int J Surg 7(6):547–549

Sung HY, Cho SH, Sim SB et al (2009) Congenital hemidiaphragmatic agenesis presenting as reversible mesenteroaxial gastric volvulus and diaphragmatic hernia: a case report. J Korean Med Sci 24(3):517–519

Tan KK, Yan ZY, Vijayan A, Chiu MT (2009) Management of diaphragmatic rupture from blunt trauma. Singap Med J 50(12):1150–1153

Boyce S, Burgul R, Pepin F, Shearer C (2008) Late presentation of a diaphragmatic hernia following laparoscopic gastric banding. Obes Surg 18(11):1502–1504

Esmer D, Alvarez-Tostado J, Alfaro A, Carmona R, Salas M (2008) Thoracoscopic and laparoscopic repair of complicated Bochdalek hernia in adult. Hernia 12(3):307–309

Gourgiotis S, Rothkegel S, Germanos S (2008) Combined diaphragmatic and urinary bladder rupture after minor motorcycle accident (report of a case and literature review). Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 14(2):163–166

Hung YH, Chien YH, Yan SL, Chen MF (2008) Adult Bochdalek hernia with bowel incarceration. J Chin Med Assoc 71(10):528–531

Mohammadhosseini B, Shirani S (2008) Incarcerated Bochdalek hernia in an adult. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 18(4):239–241

Terzi A, Tedeschi U, Lonardoni A, Furia S, Benato C, Calabro F (2008) A rare cause of dyspnea in adult: a right Bochdalek's hernia-containing colon. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 16(5):e42–44

Tsuboi K, Omura N, Kashiwagi H, Kawasaki N, Suzuki Y, Yanaga K (2008) Delayed traumatic diaphragmatic hernia after open splenectomy: report of a case. Surg Today 38(4):352–354

Vogelaar FJ, Adhin SK, Schuttevaer HM (2008) Delayed intrathoracic gastric perforation after obesity surgery: a severe complication. Obes Surg 18(6):745–746

Wu YS, Lin YY, Hsu CW, Chu SJ, Tsai SH (2008) Massive ipsilateral pleural effusion caused by transdiaphragmatic intercostal hernia. Am J Emerg Med 26(2):252.e253–254

Campbell AS, O'Donnell ME, Lee J (2007) Mediastinal shift secondary to a diaphragmatic hernia: a life-threatening combination. Hernia 11(4):377–379

Igai H, Yokomise H, Kumagai K, Yamashita S, Kawakita K, Kuroda Y (2007) Delayed hepatothorax due to right-sided traumatic diaphragmatic rupture. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 55(10):434–436

Rifki Jai S, Bensardi F, Hizaz A, Chehab F, Khaiz D, Bouzidi A (2007) A late post-traumatic diaphragmatic hernia revealed during pregnancy by post-partum respiratory distress. Arch Gynecol Obstet 276(3):295–298

Rosen MJ, Ponsky L, Schilz R (2007) Laparoscopic retroperitoneal repair of a right-sided Bochdalek hernia. Hernia 11(2):185–188

Rout S, Foo FJ, Hayden JD, Guthrie A, Smith AM (2007) Right-sided Bochdalek hernia obstructing in an adult: case report and review of the literature. Hernia 11(4):359–362

Barrett J, Satz W (2006) Traumatic, pericardio-diaphragmatic rupture: an extremely rare cause of pericarditis. J Emerg Med 30(2):141–145

Iso Y, Sawada T, Rokkaku K et al (2006) A case of symptomatic Morgagni's hernia and a review of Morgagni's hernia in Japan (263 reported cases). Hernia 10(6):521–524

Testini M, Vacca A, Lissidini G, Di Venere B, Gurrado A, Loizzi M (2006) Acute intrathoracic gastric volvulus from a diaphragmatic hernia after left splenopancreatectomy: report of a case. Surg Today 36(11):981–984

Barakat MJ, Vickers JH (2005) Necrotic gangrenous intrathoracic appendix in a marfanoid adult patient: a case report. BMC Surg. 5:4

Chai Y, Zhang G, Shen G (2005) Adult Bochdalek hernia complicated with a perforated colon. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 130(6):1729–1730

Gupta V, Singhal R, Ansari MZ (2005) Spontaneous rupture of the diaphragm. Eur J Emerg Med 12(1):43–44

Ransom P, Cornelius P (2005) Stabbing chest pain: a case of intermittent diaphragmatic herniation. Emerg Med J 22(6):460–461

Tiberio GA, Portolani N, Coniglio A, Baiocchi GL, Vettoretto N, Giulini SM (2005) Traumatic lesions of the diaphragm. Our experience in 33 cases and review of the literature. Acta Chir Belg 105(1):82–88

Abboud B, Jaoude JB, Riachi M, Sleilaty G, Tabet G (2004) Intrathoracic transverse colon and small bowel infarction in a patient with traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Case report and review of the literature. J Med Liban 52(3):168–170

Dalton AM, Hodgson RS, Crossley C (2004) Bochdalek hernia masquerading as a tension pneumothorax. Emerg Med J 21(3):393–394

Kara E, Kaya Y, Zeybek R, Coskun T, Yavuz C (2004) A case of a diaphragmatic rupture complicated with lacerations of stomach and spleen caused by a violent cough presenting with mediastinal shift. Ann Acad Med Singap 33(5):649–650

Sirbu H, Busch T, Spillner J, Schachtrupp A, Autschbach R (2005) Late bilateral diaphragmatic rupture: challenging diagnostic and surgical repair. Hernia 9(1):90–92

Niwa T, Nakamura A, Kato T et al (2003) An adult case of Bochdalek hernia complicated with hemothorax. Respiration 70(6):644–646

Guven H, Malazgirt Z, Dervisoglu A, Danaci M, Ozkan K (2002) Morgagni hernia: rare presentations in elderly patients. Acta Chir Belg 102(4):266–269

Kanazawa A, Yoshioka Y, Inoi O, Murase J, Kinoshita H (2002) Acute respiratory failure caused by an incarcerated right-sided adult Bochdalek hernia: report of a case. Surg Today 32(9):812–815

Sato M, Kosaka S (2002) Minimally invasive diagnosis and treatment of traumatic rupture of the right hemidiaphragm with liver herniation. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 50(12):515–517

Bujanda L, Larrucea I, Ramos F, Munoz C, Sanchez A, Fernandez I (2001) Bochdalek's hernia in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol 32(2):155–157

Carreno G, Sanchez R, Alonso RA et al (2001) Laparoscopic repair of Bochdalek's hernia with gastric volvulus. Surg Endosc 15(11):1359

Fisichella PM, Perretta S, Di Stefano A et al (2001) Chronic liver herniation through a right Bochdalek hernia with acute onset in adulthood. Ann Ital Chir 72(6):703–705

Prieto Nieto I, Perez Robledo JP, Rosales Trelles V, De Miguel IR, Fernandez Prieto A, Calvo CA (2001) Gastric incarceration and perforation following posttraumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Acta Chir Belg 101(2):81–83

Pross M, Manger T, Mirow L, Wolff S, Lippert H (2000) Laparoscopic management of a late-diagnosed major diaphragmatic rupture. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 10(2):111–114

Saito Y, Yamakawa Y, Niwa H et al (2000) Left diaphragmatic hernia complicated by perforation of an intrathoracic gastric ulcer into the aorta: report of a case. Surg Today 30(1):63–65

De Waele JJ, Vermassen FE (1999) Splenic herniation causing massive haemothorax after blunt trauma. J Accid Emerg Med 16(5):383–384

Colliver C, Oller DW, Rose G, Brewer D (1997) Traumatic intrapericardial diaphragmatic hernia diagnosed by echocardiography. J Trauma 42(1):115–117

Allen MS, Trastek VF, Deschamps C, Pairolero PC (1993) Intrathoracic stomach presentation and results of operation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 105(2):253–258

Girzadas DV Jr, Fligner DJ (1991) Delayed traumatic intrapericardial diaphragmatic hernia associated with cardiac tamponade. Ann Emerg Med 20(11):1246–1247

Thomas S, Kapur B (1991) Adult Bochdalek hernia—clinical features, management and results of treatment. Jpn J Surg 21(1):114–119

Bush CA, Margulies R (1990) Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia and intestinal obstruction due to penetrating trunk wounds. South Med J 83(11):1347–1350

Chidamdaram M, Eyres KS, Szabolcs Z, Ionescu MI (1988) Management problems of coincident traumatic diaphragmatic hernia and myocardial infarction. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 36(3):167–169

Feliciano DV, Cruse PA, Mattox KL et al (1988) Delayed diagnosis of injuries to the diaphragm after penetrating wounds. J Trauma 28(8):1135–1144

Gardezi SA, Chaudhry AM, Sial GA et al (1986) Congenital diaphragmatic hernia in the adult. J Pak Med Assoc 36(1):16–20

Saber WL, Moore EE, Hopeman AR, Aragon WE (1986) Delayed presentation of traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. J Emerg Med 4(1):1–7

Symbas PN, Vlasis SE, Hatcher C Jr (1986) Blunt and penetrating diaphragmatic injuries with or without herniation of organs into the chest. Ann Thorac Surg 42(2):158–162

Clark DE, Wiles CS 3rd, Lim MK, Dunham CM, Rodriguez A (1983) Traumatic rupture of the pericardium. Surgery 93(4):495–503

Clarke DL, Greatorex B, Oosthuizen GV, Muckart DJ (2009) The spectrum of diaphragmatic injury in a busy metropolitan surgical service. Injury 40(9):932–937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2008.10.042

Mjoli M, Oosthuizen G, Clarke D, Madiba T (2015) Laparoscopy in the diagnosis and repair of diaphragmatic injuries in left-sided penetrating thoracoabdominal trauma: laparoscopy in trauma. Surg Endosc 29(3):747–752. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3710-8

Bairagi A, Moodley SR, Hardcastle TC, Muckart DJ (2010) Blunt rupture of the right hemidiaphragm with herniation of the right colon and right lobe of the liver. J Emerg Trauma Shock 3(1):70–72. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-2700.58659

Kwon J, Lee JC, Moon J (2019) Diagnostic significance of diaphragmatic height index in traumatic diaphragmatic rupture. Ann Surg Treat Res 97(1):36–40. https://doi.org/10.4174/astr.2019.97.1.36

Houston J, Jalil R, Isla A (2012) Delayed presentation of post-traumatic diaphragm rupture repaired by laparoscopy. BMJ Case Rep 2012:bcr-2012-007372. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2012-007372

Powell L, Chai J, Shaikh A, Shaikh A (2019) Experience with acute diaphragmatic trauma and multiple rib fractures using routine thoracoscopy. J Thorac Dis 11(Suppl 8):S1024–S1028. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2019.03.72

Shaban Y, Elkbuli A, McKenney M, Boneva D (2020) Traumatic diaphragmatic rupture with transthoracic organ herniation: a case report and review of literature. Am J Case Rep 21:e919442. https://doi.org/10.12659/AJCR.919442

Chughtai T, Ali S, Sharkey P, Lins M, Rizoli S (2009) Update on managing diaphragmatic rupture in blunt trauma: a review of 208 consecutive cases. Can J Surg 52(3):177–181

Pehar M, Vukoja I, Rozić D, Mišković J (2012) Spontaneous diaphragmatic rupture related to local invasion by retroperitoneal liposarcoma. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 94(1):e18–e19. https://doi.org/10.1308/003588412x13171221499423

Ercan M, Aziret M, Karaman K, Bostancı B, Akoğlu M (2016) Dual mesh repair for a large diaphragmatic hernia defect: an unusual case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 28:266–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.10.015

Muroni M, Provenza G, Conte S et al (2010) Diaphragmatic rupture with right colon and small intestine herniation after blunt trauma: a case report. J Med Case Rep 4:289. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1947-4-289

Aborajooh EA, Al-Hamid Z (2020) Case report of traumatic intrapericardial diaphragmatic hernia: laparoscopic composite mesh repair and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep 70:159–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2020.04.077

Vyas PK, Godbole C, Bindroo SK, Mathur RS, Akula B, Doctor N (2016) Case-based discussion: an unusual manifestation of diaphragmatic hernia mimicking pneumothorax in an adult male. Int J Emerg Med 9(1):11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-016-0108-5

Öz N, Kargı AB, Zeybek A (2015) Co-existence of a rare dyspnea with pericardial diaphragmatic rupture and pericardial rupture: a case report. Kardiochir Torakochirurgia Pol 12(2):173–175. https://doi.org/10.5114/kitp.2015.52865

Lee JY, Sul YH, Ye JB, Ko SJ, Choi JH, Kim JS (2018) Right-sided diaphragmatic rupture in a poly traumatized patient. Ann Surg Treat Res 94(6):342–345. https://doi.org/10.4174/astr.2018.94.6.342

Kumar A, Bagaria D, Ratan A, Gupta A (2017) Missed diaphragmatic injury after blunt trauma presenting with colonic strangulation: a rare scenario. BMJ Case Rep 2017:bcr2017221220. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2017-221220

Lim BL, Teo LT, Chiu MT, Asinas-Tan ML, Seow E (2017) Traumatic diaphragmatic injuries: a retrospective review of a 12-year experience at a tertiary trauma centre. Singap Med J 58(10):595–600. https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2016185

Gu P, Lu Y, Li X, Lin X (2019) Acute and chronic traumatic diaphragmatic hernia: 10 years experience. PLoS ONE 14(12):e0226364. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226364

Simpson J, Lobo DN, Shah AB, Rowlands BJ (2000) Traumatic diaphragmatic rupture: associated injuries and outcome. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 82(2):97–100

Ganie FA, Lone H, Lone GN et al (2013) Delayed presentation of traumatic diaphragmatic hernia: a diagnosis of suspicion with increased morbidity and mortality. Trauma Mon 18(1):12–16. https://doi.org/10.5812/traumamon.7125

Xenaki S, Lasithiotakis K, Andreou A, Chrysos E, Chalkiadakis G (2014) Laparoscopic repair of posttraumatic diaphragmatic rupture. Report of three cases. Int J Surg Case Rep 5(9):601–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2014.07.007

Davoodabadi A, Fakharian E, Mohammadzadeh M, Abdorrahim Kashi E, Mirzadeh AS (2012) Blunt traumatic hernia of diaphragm with late presentation. Arch Trauma Res 1(3):89–92. https://doi.org/10.5812/atr.7593

Nain PS, Singh K, Matta H, Parmar A, Gupta PK, Batta N (2014) Review of 9 cases of diaphragmatic injury following blunt trauma chest; 3 years experience. Indian J Surg 76(4):261–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-012-0602-9

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Perrone, G., Giuffrida, M., Annicchiarico, A. et al. Complicated Diaphragmatic Hernia in Emergency Surgery: Systematic Review of the Literature. World J Surg 44, 4012–4031 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-020-05733-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-020-05733-6