Abstract

Background

Acute colonic diverticulitis is a common clinical condition. Severity of the disease is based on clinical, laboratory, and radiological investigations and dictates the need for medical or surgical intervention. Recent clinical trials have improved the understanding of the natural history of the disease resulting in new approaches to and better evidence for the management of acute diverticulitis.

Methods

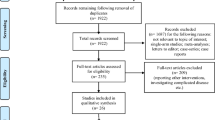

We searched the Cochrane Library (years 2004–2015), MEDLINE (years 2004–2015), and EMBASE (years 2004–2015) databases. We used the search terms “diverticulitis, colonic” or “acute diverticulitis” or “divertic*” in combination with the terms “management,” “antibiotics,” “non-operative,” or “surgery.” Registers for clinical trials (such as the WHO registry and the https://clinicaltrials.gov/) were searched for ongoing, recruiting, or closed trials not yet published.

Results

Antibiotic treatment can be avoided in simple, non-complicated diverticulitis and outpatient management is safe. The management of complicated disease, ranging from a localized abscess to perforation with diffuse peritonitis, has changed towards either percutaneous or minimally invasive approaches in selected cases. The role of laparoscopic lavage without resection in perforated non-fecal diverticulitis is still debated; however, recent evidence from two randomised controlled trials has found a higher re-intervention in this group of patients.

Conclusions

A shift in management has occurred towards conservative management in acute uncomplicated disease. Those with uncomplicated acute diverticulitis may be treated without antibiotics. For complicated diverticulitis with purulent peritonitis, the use of peritoneal lavage appears to be non-superior to resection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Acute diverticulitis is among the top 10 diagnoses of patients presenting to the general physician or at the emergency department with acute abdominal pain [1]. The role of the clinician is to establish the severity of the disease, based on the clinical findings and results of appropriate investigations. This will then determine the subsequent need for medical or surgical intervention. As evident from a number of guidelines issued in the past, there has been considerable variation in recommendations and approaches to patients with acute diverticulitis [2–8]. Much of the variation has been based on a weak or complete lack of evidence for which to make recommendations. Also, considerable variation in strategies and management choices still exist between and within regions [9, 10]. As our understanding of this disease has evolved, so have the available strategies for managing it. As a consequence, a less invasive approach to the medical and surgical treatment of acute diverticulitis has emerged.

In this contemporary review, we report on the recent understanding of acute diverticulitis as a spectrum between simple, self-resolving disease to the need for medical, radiological, and surgical intervention. We aimed to review the best evidence for a stratified management of patients with either acute uncomplicated or complicated diverticulitis.

Methods

We aimed to identify studies which reported on the diagnosis of acute diverticulitis along with its subsequent medical and surgical management. The databases including the Cochrane Library (years 2004–2015), MEDLINE (years 2004–2015), and EMBASE (years 2004–2015) were searched. We used the search terms “diverticulitis, colonic” or “acute diverticulitis” or “divertic*” in combination with the terms “management,” “antibiotics,” “non-operative,” or “surgery.” We included systematic reviews and meta-analyses pertinent to the topics, along with reported randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and cohort studies. Registers for clinical trials (such as the WHO registry and the https://clinicaltrials.gov/) were searched for ongoing, recruiting, or closed trials not yet published. We largely selected publications from the search period in the English language, but did not exclude commonly referenced and highly regarded older publications. We also searched the reference lists of articles identified by this search strategy and selected those we judged relevant by the above criteria.

A formal grading of all evidence, such as by the Oxford Evidence-Based Medicine or Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation , was not systematically done, unless already performed and reported in identified studies. However, the type of study or collective data were specifically cited where applicable and, where evidence is weak or even lacking, this has been commented on in each specific section.

Results

In patients with acute abdominal pain presenting to the emergency department, reliance on clinical diagnosis of diverticulitis can result in too many missed diagnoses of diverticulitis (up to 36 %) or incorrect suspicion of diverticulitis [11–13]. A simplified clinical decision rule has been proposed with an excellent positive predictive value (81–100 %) for diagnosis of acute diverticulitis in patients who present with the complete triad of ‘absence of vomiting,’ ‘tenderness in the left lower quadrant,’ and ‘CRP of more than 50 mg/L.’ However, the triad alone identifies only up to 25 % of patients with diverticulitis [13]. Imaging is thus important to increase diagnostic accuracy and allow risk stratification early in the clinical course.

Diagnostic imaging

In studies with selected patients, computed tomography (CT) demonstrates high accuracy for the diagnosis of acute diverticulitis with a sensitivity of 94 % (87–97 %) and a specificity of 99 % (90–100 %) [14, 15]. CT is better than ultrasound (US) in performing an alternative diagnosis in patients with clinical suspicion of diverticulitis and allows better detection of complicated disease. In a large prospective cohort of unselected patients, presenting with acute abdominal pain, sensitivity for the diagnosis of acute diverticulitis was somewhat lower (81 % (74–88 %)) than that in selected patients but specificity remained high (99 % (98–99 %)) [14]. US had a moderate sensitivity (61 % (52–70 %)) but a good specificity (99 % (99–100 %)) for the diagnosis of acute diverticulitis in an unselected population [14].

As treatment strategies have become less aggressive and more tailored to the stage of diverticulitis, accurate staging of the disease has become increasingly important (Table 1). Hinchey’s traditional classification (Fig. 1) for perforated diverticulitis from 1978 was based on clinical and surgical findings [16, 17]. The modern Hinchey classification is a fully CT-based modification of the original Hinchey classification [18]. Ambrosetti defined a further classification based on CT imaging [19]. Both classifications do not specify the various stages of complicated diverticulitis. A new CT-based classification focuses on complicated diverticulitis only, which is an important extension of existing classifications (Table 2) [20]. Classification may help compare patients across cohorts and identify patients at risk of further complications, such as those with small abscesses. It may also allow identification of patients for successful conservative treatment of complicated diverticulitis.

Hinchey classification. The classical Hinchey classification of a mesocolic/pericolic inflammation and/or abscess, b a (larger) pelvic abscess, c perforation with localized or generalized purulent peritonitis, and d perforation with fecal contamination and generalized peritonitis

Treatment strategies

The treatment of acute diverticulitis is stratified and should be considered either as a treatment of a mild and non-complex inflammatory disease (which is often self-limiting), or a treatment of a severe and complex disease with systemic affection. Traditionally, patients were put nil by mouth, prescribed intravenous antibiotics, and admitted to hospital as part of the treatment regimen.

Uncomplicated acute diverticulitis

Outpatient management

Outpatient management of patients with simple uncomplicated acute diverticulitis is feasible in those with tolerance to oral intake, no severe comorbidity, and with appropriate social support [5]. There is no published evidence that dietary alterations (e.g. high-fiber diets) or laxatives have any effect on disease outcome [5].

Indications and role of antibiotics

Simple acute diverticulitis is in the majority of cases a self-limiting process. Antibiotics are still routinely prescribed in many cases of uncomplicated disease and continue to be recommended in some guidelines [21]. A Cochrane systematic review from 2012 concluded that the role of antibiotics in uncomplicated acute diverticulitis is not adequately investigated [22]. However, recent studies on the best treatment for CT-proven mild, uncomplicated diverticulitis demonstrate that these patients can be managed expectantly without antibiotics, either as inpatients or as outpatients according to the severity of the complaints (Table 2) [23]. One randomized controlled trial (AVOD trial) demonstrated no benefit of routine use of antibiotics over no antibiotics in terms of complications, need for emergency surgery, hospital stay, or recurrence at 12 months in 623 patients with mild diverticulitis [24]. Unfortunately, 40 % of the included patients in this trial had a recurrent episode of diverticulitis rather than a primary episode. A long accrual period and no standardized antibiotic treatment may also have resulted in a performance bias. A second RCT, with a multicenter, randomized, controlled, pragmatic, non-inferiority design (DIABOLO), found no difference in median time to recovery, readmission rates, complications, recurrent diverticulitis, or need for sigmoid resection in 528 patients with a CT-proven first episode of acute, left-sided, uncomplicated diverticulitis, between antibiotic treatment and simply observation [25].

Complicated acute diverticulitis

The management of complicated diverticulitis continues to be debated. Complicated diverticulitis includes acute diverticulitis with abscesses (Hinchey II), purulent peritonitis (Hinchey III), and fecal peritonitis (Hinchey IV). Clearly, patients who are septic after perforated diverticulitis or have diffuse peritonitis with evidence of free air require an immediate operation with appropriate resuscitation if deemed fit for surgery. On the other hand, those who are non-septic and have contained perforations may be managed operatively or non-operatively, depending on subtle clinical details and the evolution of the course of the disease.

In the absence of compelling symptoms and signs, Hinchey grade I or II diverticulitis is usually managed without surgery. Hinchey II disease is frequently treated with antibiotics and percutaneous drainage (for abscess size >5 cm). Hinchey III and IV disease typically requires an operation. The controversy concerns the need for resection with a diverting stoma (so-called Hartmann’s procedure) versus resection with a primary anastomosis. Added to the debate is the approach of laparoscopic lavage (with no resection) for perforation and generalized peritonitis (Hinchey grade III) without fecal contamination.

Evolving treatment strategies

The treatment of diverticulitis has evolved towards a more conservative and minimally invasive approach (Fig. 2). The standard of care for complicated or perforated diverticulitis has evolved from a Hartmann’s procedure, to resection and primary anastomosis, then to treatment with antibiotics and percutaneous drainage in a carefully selected subset of patients (Hinchey II).

Evolving management strategies for acute complicated diverticulitis. Evolving concept in surgical management with the development of adjunct therapies and development of supportive disciplines. A more tailored, personalized treatment is being developed. Results from ongoing RCTs will further provide risk–benefit estimates for appropriate decision making

Two randomized trials have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of primary anastomosis in complicated diverticulitis. The first trial by Binda et al. was stopped prematurely after inclusion of only 90 out of the targeted 600 patients, because of slow accrual [26]. Being underpowered, the mortality (2.9 vs 10.7 %; P = 0.247) and morbidity (35.3 vs 46.4 %; P = 0.38) were not significantly different between the patients undergoing resection with primary anastomosis and those with Hartmann procedure. The second trial of Oberkofler et al. reported a comparable overall complication rate when both resection and stoma reversal operations were evaluated (84 vs. 80 %, P = 0.813), but with more serious complications in the Hartmann’s group [27].

The choice of performing either a Hartmann’s procedure or a primary anastomosis in the individual patient needs careful clinical evaluation of the perceived risks and benefits. Recommendations are still largely based on case studies and expert opinion [28]. Results from the resection arm in the LADIES trial will likely provide some answers in the future (Fig. 2) [29]. The level of training of the operating surgeon also dictates which treatment strategy is used.

Laparoscopic lavage

The use of laparoscopic lavage for perforated purulent diverticulitis has gradually increased since its introduction in 1996. Prospective and retrospective data have shown that evacuating the pus and lavaging the peritoneal cavity through the laparoscope is enough to treat selected patients with perforated diverticulitis. The proponents of this method believe in its simplicity and effectiveness, whereas the skeptics argue that too many patients need urgent surgery afterwards. Four trials have been undertaken in recent years and early results from three of these have now been published (Fig. 2). The LADIES trial is a four-arm RCT from the Netherlands, investigating the surgical treatment of complicated diverticulitis [29]. The LOLA arm, designed to investigate whether laparoscopic lavage and drainage is a safe and effective treatment for patients with purulent peritonitis was stopped prematurely after recruitment of 90 patients, due to a significantly increased number of adverse events in the lavage group compared to the sigmoidectomy group in interim analysis. Need for in-hospital surgical re-interventions accounted for most of the adverse events with 18 occurring in the lavage group compared to two in the sigmoidectomy group (P = 0.0011). The authors have concluded that laparoscopic lavage was not superior to sigmoidectomy in terms of major morbidity and mortality at 12 months following surgery and that re-intervention rates are higher in the laparoscopic arm [29]. They also note that in 75 % of those in the laparoscopic arm initial lavage does allow source control but better measures are required to identify those with persistent perforations and perforated cancers.

The results of a second study, the SCANDIV trial, have recently been reported. The authors found an increase in reoperations in those treated with lavage without fecal peritonitis compared to colonic resection (20.3 % (15/74) vs 5.7 % (4/70) P = 0.01). The authors conclude that laparoscopic lavage does not reduce severe short-term post-operative complications and has led to worse outcomes such as higher reoperation rates and therefore could not support the use of lavage for perforated diverticulitis [30]. However, the long-term results comparing the need for future events (stoma take-backs, new diverticulitis episodes, need for elective procedures) are awaited for overall morbidity and outcome comparison.

Currently, the LapLAND study (NCT01019239) from Ireland and the DILALA (ISRCTN82208287) are comparing laparoscopic lavage versus resection for Hinchey 3 diverticulitis. The DILALA short-term results in 83 perforated Hinchey III diverticulitis patients randomized between laparoscopic lavage and Hartmann procedure have demonstrated the feasibility of lavage [31]. Long-term outcomes are now needed to evaluate the overall benefit such as avoidance of stoma formation, mortality, and reoperation rates for recurrent symptoms or attacks. Current evidence from RCTs therefore suggests a higher short-term reoperation rate in those treated with laparoscopic lavage and no evidence of a reduction in major complications.

Outcomes and follow-up

Recurrence

Reported recurrence rates following an episode of acute diverticulitis requiring hospital admission for medical treatment vary from 13.3 to 42 %, depending on the diagnostic criteria used for acute diverticulitis and the follow-up period reported. The largest of these retrospective series reported data on 2366 medically treated patients with a median follow-up of 8.9 years with a recurrence rate of 13.3 % [32]. The majority of recurrences reported in these studies occurred early following the initial presentation. The true burden of recurrent disease may be greater as none of these studies reported episodes of recurrence treated in the community.

Recent studies have proposed that the majority of patients do not recur and that, if they do, the severity of the disease is not likely to be higher than that in the previous uncomplicated episodes [33]. In fact, as demonstrated in the DIVER trial, the frequency of perforation nearly halves with each subsequent episode, from 25 % in the first episode to 12 % with the second, to 6 % with the third, and to 1 % with further episodes [34]. Other factors, such as age, severity of the disease, immuno-compromising co-morbidities, family history, or extent of the involved colon, have not been clearly proven as risk factors for recurrence.

Recurrent diverticulitis does not seem to be age dependent. There are conflicting data regarding the risk of recurrence for younger (age <50 years) versus older patients. In a systematic review, disease recurrence rates in younger patients were significantly higher than those of elderly patients (RR 1.70, 95 % CI 1.31–2.21) [35]. However, the included studies did not report their follow-up period per group clearly, thus potentially introducing a follow-up bias. More recent data suggest that recurrence rate and outcome are not worse in younger patients. In a recent large retrospective cohort, recurrence rate after a median follow-up of 22 months is comparable among groups (25.6 % (111 of 463) for younger patients versus 23.8 % (208 of 978) in patients over 50 years of age [36].

Mortality

The largest studies reporting the mortality associated with hospital admission for acute diverticulitis have used data from the NIS and reported in-hospital mortality only. These studies have reported a reduction in mortality following hospital admission over time with a reduction from 1.6 % in 1998 to 1.0 % during 2004–2005 and a 55 % relative reduction in-hospital mortality from 4.5 to 2.5 % during 2002–2007 with a reduction in mortality following surgery for acute diverticulitis from 5.7 to 4.3 % across the same period [37].

Need for colonoscopy at follow-up

Current guidelines still recommend routine follow-up colonoscopy after a first attack of acute diverticulitis to confirm the diagnosis and exclude malignancy [38]. The recommendation for colonoscopy after an episode of acute diverticulitis is merely based on expert opinion and dates back to the time before widespread use of CT to diagnose acute diverticulitis. Colonoscopy is burdensome, costly, and time-consuming and has the risk of procedure-related morbidity. The yield of colonoscopy after acute diverticulitis diagnosed by adequate imaging techniques is questionable.

There are two different issues posed by those in favor of colonoscopy: (a) the need to exclude malignancy (fear of misdiagnosis) and (b) a presumed higher risk of colorectal carcinoma (CRC) in patients who encountered acute diverticulitis. Patients with diverticulosis or diverticulitis have no higher incidence of polyps or CRC when using age-stratified analysis [39]. The yield of advanced colonic neoplasia during colonoscopy after acute diverticulitis is equivalent to that detected in asymptomatic average-risk screening participants. A systematic review has found an estimated pooled prevalence of 5.0 % (CI 3.8–6.7 %) for advanced colonic neoplasia and 1.5 % (CI 1.0–2.3 %) for CRC at follow-up after an episode of CT-confirmed acute diverticulitis [40]. Follow-up colonoscopy may be needed in patients with an equivocal diagnosis at CT or with a protracted clinical course. Patients presenting with rectal bleeding or with change in bowel habit prior to their initial episode may also warrant a colonoscopy. A recent study has compared colonoscopy and CTC in the follow-up of 108 diverticulitis patients: CTC is better tolerated but the detection accuracy of small polyps is poor, and no advanced neoplasia was found in this cohort [41].

Elective colectomy after resolved acute diverticulitis

Routine elective (segmental) colectomy after two attacks of diverticulitis was once considered standard of care, but this has changed with new evidence [42]. The risk of perforation and peritonitis decreases with each attack, contrary to previous beliefs [43]. The outcomes following elective surgery in patients having undergone successful non-operative management indicate that patients have more complications and higher costs than those following resection for cancer with up to one in five patients having persistent symptoms [44, 45]. Results from the DIRECT trial (NTR1478), a randomized comparison of elective resection for recurrent diverticulitis versus non-operative treatment, are expected following the interruption of the trial after interim analysis [46]. Given the relative confusion that exists about the natural history of uncomplicated diverticulitis, it is recommended that the decision to offer an elective colectomy should be individualized.

Discussion

This review presents current available evidence on the diagnosis and the medical and surgical treatment of patients with acute diverticulitis and its complications. Current evidence supports a stratified approach to management based on clinical and radiological features. Due to the broad nature of this review, we were unable to follow standard methodologies for systemic review. However, we have reported our search strategy and only included articles which were relevant to the current management of acute diverticulitis and its complications.

The diagnosis of acute diverticulitis is made on clinical suspicion; however, to allow appropriate risk stratification diagnostic imaging is essential. The modality of choice for radiological investigation is CT. It allows stratification of patients into those with uncomplicated simple acute diverticulitis and those with complicated disease. This distinction is imperative if current best evidence is to be applied to this group of patients. Current guidelines suggest that all patients with a clinical suspicion of acute diverticulitis and no prior history should have the diagnosis confirmed by radiological imaging on that admission [47].

Antibiotic therapy has been mandated in patients with acute diverticulitis; however, there is now evidence from two RCTs and a Cochrane review, which suggest that in those patients with CT-confirmed uncomplicated acute diverticulitis antibiotics can be safely withheld [24, 25]. The full results of the DIABOLO trial will be required before firm recommendations on the use of antibiotics in this group of patients can be issued; however, the currently reported results are encouraging.

In cases of complicated disease with free perforation and purulent peritonitis, the current trend towards the use of laparoscopic lavage has not been supported by two recently published trials [29, 30]. Laparoscopic lavage in the short term was associated with increased morbidity and mortality with higher re-intervention rates when compared to sigmoid resection. Long-term results from these studies will be required to determine if any long-term advantages to minimally invasive treatments such as stoma avoidance and long-term need for surgical intervention are apparent.

In patients undergoing an open procedure, there is no strong evidence to support the use of a Hartmann’s procedure or primary anastomosis with only two small trials completed to date both of which lacked power [26]. The choice between the two procedures often comes down to the level of experience of the operating surgeon along with patient specific risk factors such as comorbidity, sepsis, and degree of contamination. Results from the resection arm of the LADIES trial may help inform current practice in this area.

Following admission with acute diverticulitis, recurrence rates are low and current evidence suggests no increase in risk of recurrence in younger patients. Mandated elective resection after two episodes of acute diverticulitis is no longer supported given the low risk of recurrence and subsequent development of complicated disease; therefore, decisions regarding elective resection should be made on an individual patient basis.

Current understanding of acute diverticulitis permits a diversified management plan, and a stratified approach tailored to the disease severity. Most mild episodes can be treated as an outpatient without the need for antibiotics or dietary restrictions (Table 3). The optimal surgical strategy is to be further refined.

References

Viniol A, Keunecke C, Biroga T et al (2014) Studies of the symptom abdominal pain—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam Pract 31(5):517–529

Vennix S, Morton DG, Hahnloser D et al (2014) Systematic review of evidence and consensus on diverticulitis: an analysis of national and international guidelines. Colorectal Dis 16(11):866–878

Leifeld L, Germer CT, Bohm S et al (2014) S2 k guidelines diverticular disease/diverticulitis. Z Gastroenterol 52(7):663–710

Pappalardo G, Frattaroli FM, Coiro S et al (2013) Effectiveness of clinical guidelines in the management of acute sigmoid diverticulitis. Results of a prospective diagnostic and therapeutic clinical trial. Ann Ital Chir 84:171–177

Andeweg CS, Mulder IM, Felt-Bersma RJ et al (2013) Guidelines of diagnostics and treatment of acute left-sided colonic diverticulitis. Dig Surg 30(4–6):278–292

Fujita T (2012) Feasibility of the practice guidelines for colonic diverticulitis. Surgery 151(3):491–492

Andersen JC, Bundgaard L, Elbrond H et al (2012) Danish national guidelines for treatment of diverticular disease. Dan Med J 59(5):C4453

SSAT. SSAT Patient Care Guidelines: Surgical Treatment of Diverticulitis. 2007 [cited 2014 31.12.2014]; Available from: http://www.ssat.com/cgi-bin/divert.cgi

Jafferji MS, Hyman N (2014) Surgeon, not disease severity, often determines the operation for acute complicated diverticulitis. J Am Coll Surg 218(6):1156–1161

O’Leary DP, Lynch N, Clancy C et al (2015) International, Expert-Based, consensus statement regarding the management of acute diverticulitis. JAMA Surg 150(9):899–904

Lameris W, van Randen A, van Es HW et al (2009) Imaging strategies for detection of urgent conditions in patients with acute abdominal pain: diagnostic accuracy study. BMJ 338:b2431

Laurell H, Hansson LE, Gunnarsson U (2007) Acute diverticulitis–clinical presentation and differential diagnostics. Colorectal Dis 9(6):496–501 dicussion 501–492

Kiewiet JJ, Andeweg CS, Laurell H et al (2014) External validation of two tools for the clinical diagnosis of acute diverticulitis without imaging. Dig Liver Dis 46(2):119–124

van Randen A, Lameris W, van Es HW et al (2011) A comparison of the accuracy of ultrasound and computed tomography in common diagnoses causing acute abdominal pain. Eur Radiol 21(7):1535–1545

Laméris W, Randen A, Bipat S et al (2008) Graded compression ultrasonography and computed tomography in acute colonic diverticulitis: meta-analysis of test accuracy. Eur Radiol 18(11):2498–2511

Hinchey EJ, Schaal PG, Richards GK (1978) Treatment of perforated diverticular disease of the colon. Adv Surg 12:85–109

Wasvary H, Turfah F, Kadro O et al (1999) Same hospitalization resection for acute diverticulitis. Am Surg 65(7):632–635 discussion 636

Kaiser AM, Jiang JK, Lake JP et al (2005) The management of complicated diverticulitis and the role of computed tomography. Am J Gastroenterol 100(4):910–917

Ambrosetti P, Grossholz M, Becker C et al (1997) Computed tomography in acute left colonic diverticulitis. Br J Surg 84(4):532–534

Dharmarajan S, Hunt SR, Birnbaum EH et al (2011) The efficacy of nonoperative management of acute complicated diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum 54(6):663–671

Schechter S, Mulvey J, Eisenstat TE (1999) Management of uncomplicated acute diverticulitis: results of a survey. Dis Colon Rectum 42(4):470–475 discussion 475–476

Shabanzadeh DM, Wille-Jorgensen P (2012) Antibiotics for uncomplicated diverticulitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 11(92):CD009092

de Korte N, Unlu C, Boermeester MA et al (2011) Use of antibiotics in uncomplicated diverticulitis. Br J Surg 98(6):761–767

Chabok A, Pahlman L, Hjern F et al (2012) Randomized clinical trial of antibiotics in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. Br J Surg 99(4):532–539

Unlu C, de Korte N, Daniels L et al (2010) A multicenter randomized clinical trial investigating the cost-effectiveness of treatment strategies with or without antibiotics for uncomplicated acute diverticulitis (DIABOLO trial). BMC Surg 10:23

Binda GA, Karas JR, Serventi A et al (2012) Primary anastomosis vs nonrestorative resection for perforated diverticulitis with peritonitis: a prematurely terminated randomized controlled trial. Colorectal Dis 14(11):1403–1410

Oberkofler CE, Rickenbacher A, Raptis DA et al (2012) A multicenter randomized clinical trial of primary anastomosis or Hartmann’s procedure for perforated left colonic diverticulitis with purulent or fecal peritonitis. Ann Surg 256(5):819–826 discussion 826–817

Moore FA, Catena F, Moore EE et al (2013) Position paper: management of perforated sigmoid diverticulitis. World J Emerg Surg 8(1):55

Vennix S, Musters GD, Mulder IM et al (2015) Laparoscopic peritoneal lavage or sigmoidectomy for perforated diverticulitis with purulent peritonitis: a multicentre, parallel-group, randomised, open-label trial. Lancet 386(10000):1269–1277

Schultz JK, Yaqub S, Wallon C et al (2015) Laparoscopic lavage vs primary resection for acute perforated diverticulitis: The SCANDIV Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 314(13):1364–1375

Angenete E, Thornell A, Burcharth J et al (2016) Laparoscopic lavage is feasible and safe for the treatment of perforated diverticulitis with purulent peritonitis: the first results from the randomized controlled trial DILALA. Ann Surg 263(1):117–122. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000001061

Broderick-Villa G, Burchette RJ, Collins JC et al (2005) Hospitalization for acute diverticulitis does not mandate routine elective colectomy. Arch Surg 140(6):576–581 discussion 581–573

Etzioni DA, Chiu VY, Cannom RR et al (2010) Outpatient treatment of acute diverticulitis: rates and predictors of failure. Dis Colon Rectum 53(6):861–865. doi:10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181cdb243

Biondo S, Golda T, Kreisler E et al (2014) Outpatient versus hospitalization management for uncomplicated diverticulitis: a prospective, multicenter randomized clinical trial (DIVER Trial). Ann Surg 259(1):38–44

Katz LH, Guy DD, Lahat A et al (2013) Diverticulitis in the young is not more aggressive than in the elderly, but it tends to recur more often: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 28(8):1274–1281

Unlu C, van de Wall BJ, Gerhards MF et al (2013) Influence of age on clinical outcome of acute diverticulitis. J Gastrointest Surg 17(9):1651–1656

Etzioni DA, Mack TM, Beart RWJ et al (2009) Diverticulitis in the United States: 1998–2005: changing patterns of disease and treatment. Ann Surg 249(2):210–217

Feingold D, Steele SR, Lee S et al (2014) Practice parameters for the treatment of sigmoid diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum 57(3):284–294

Meurs-Szojda MM (2008) J.S. Terhaar sive Droste, D.J. Kuik, et al., Diverticulosis and diverticulitis form no risk for polyps and colorectal neoplasia in 4,241 colonoscopies. Int J Colorectal Dis 23(10):979–984

Daniels L, Unlu C, de Wijkerslooth TR et al (2014) Routine colonoscopy after left-sided acute uncomplicated diverticulitis: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc 79(3):378–389 quiz 498-498.e375

Chabok A, Smedh K, Nilsson S et al (2013) CT-colonography in the follow-up of acute diverticulitis: patient acceptance and diagnostic accuracy. Scand J Gastroenterol 48(8):979–986

McDermott FD, Collins D, Heeney A et al (2014) Minimally invasive and surgical management strategies tailored to the severity of acute diverticulitis. Br J Surg 101(1):e90–e99

Buchs NC, Konrad-Mugnier B, Jannot AS et al (2013) Assessment of recurrence and complications following uncomplicated diverticulitis. Br J Surg 100(7):976–979 discussion 979

Van Arendonk KJ, Tymitz KM, Gearhart SL et al (2013) Outcomes and costs of elective surgery for diverticular disease: a comparison with other diseases requiring colectomy. JAMA Surg 148(4):316–321

Regenbogen SE, Hardiman KM, Hendren S et al (2014) Surgery for diverticulitis in the 21st century: A systematic review. JAMA Surg. 149(3):292–303

van de Wall BJ, Draaisma WA, Consten EC et al (2010) DIRECT trial. Diverticulitis recurrences or continuing symptoms: Operative versus conservative treatment. A multicenter randomised clinical trial. BMC Surg 10:25

Fozard JBJ, Armitage NC, Schofield JB et al (2011) ACPGBI position statement on elective resection for diverticulitis. Colorectal Dis 13:1–11

Author Contributions

KS and MB planned the review. All authors (MB, DH, GV, KS) drafted sections and performed literature searches. All authors contributed to several revisions of the manuscript sections towards the final version and approved the submitted manuscript.

Funding

DJH is funded by a National Institute for Health Research Post-Doctoral Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

MB has received grants for diverticulitis research from the Dutch Health Care and Efficacy Research (ZonMW), the Dutch Digestive Diseases Foundation (MLDS), and non-diverticulitis-related grants from Baxter, Abbott, Ipsen, LifeCell/Acelity, and GSK. She has spoken at a Dr Falk Pharmaceuticals Symposium as an invited speaker on diverticulitis. DH has received research funding from the Royal College of Surgeons of England, Research into Ageing, and the BUPA foundation for research on diverticular disease. He has spoken at a Dr Falk Pharmaceuticals Symposium as an invited speaker on diverticular disease. GV none. KS none.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Boermeester, M.A., Humes, D.J., Velmahos, G.C. et al. Contemporary Review of Risk-Stratified Management in Acute Uncomplicated and Complicated Diverticulitis. World J Surg 40, 2537–2545 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-016-3560-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-016-3560-8