Abstract

We used custom mega-prostheses in 57 patients with aggressive benign and malignant tumours of the proximal humerus. The most common tumour was osteosarcoma, followed by giant cell tumour and chondrosarcoma. We achieved extra-articular and wide resection margins in all primary malignant tumours and narrow margins in benign and metastatic tumours. Six patients died of disease, 4 patients developed local recurrences and 43 were continuously disease free at an average follow-up of 5.5 years (range 2–14.5 years). Five patients required revision replacements. The most common complications were proximal subluxation and aseptic loosening. Functional outcome was satisfactory in 78% of cases.

Résumé

Nous avons traité 57 malades avec une tumeur bénigne agressive ou une tumeur maligne de l’humérus proximal par résection et remplacement par prothèse massive sur mesure. La tumeur la plus commune était l’ostéosarcome suivi par la tumeur à cellules géantes et le chondrosarcome. Nous avons obtenus des résection extra — articulaires et larges dans toutes les tumeurs malignes et des résections marginales dans les tumeurs bénignes et métastatiques. Six malades sont morts de maladie, quatre malades ont développé des récidives locales et 43 étaient sans maladie à un suivi moyen de 5,5 (2–14,5) années. 5 malades ont nécessité des reprises prothétiques. Les complications les plus communes étaient la subluxation proximale et le descellement aseptique. Le résultat fonctionnel était satisfaisant dans 78% des cas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Curative resections of the tumours of proximal humerus have been made possible in this era of limb salvage, with accurate staging and clear preoperative imaging defining the margins of resection [13]. For high-grade sarcomas, careful patient selection, supported by neo-adjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy with a multi-disciplinary approach, has helped orthopaedic oncologists attain recurrence and mortality rates comparable to those with amputations [4, 5, 21, 23]. However, reconstruction of the proximal humerus remains controversial, with reports that come down for or against various options [9, 10, 20, 25]. The purpose of this study was to analyse the complications and the oncological and functional results of custom mega-prosthetic proximal humeral replacement while evaluating the prosthetic survival rates.

Materials and methods

Between April 1989 and August 2001, 63 patients with proximal humeral tumours underwent limb salvage resection and reconstruction in various institutions. We describe those 57 patients who were followed up for a minimum period of 2 years following custom mega-prosthetic replacement. There were 28 males and 29 females, mostly in the second or third decade of life, ranging in age from 8 to 69 years (mean 27.9 years). The mean follow-up period was 5.5 years.

Diagnosis and grade of tumours

There were 24 patients with osteosarcoma (Fig. 1), 11 aggressive giant cell tumours, 7 chondrosarcomas, 5 metastatic lesions and 2 cases of Ewing’s sarcoma (Table 1). Pre-operative staging evaluation was accomplished using plain radiography in all cases, computerized tomography (31 cases); magnetic resonance imaging (15 cases) and technetium bone scans (12 patients) to assess the soft tissue spread and distant bone metastases. Angiography was performed in four patients.

Histopathological diagnosis was established pre-operatively with open biopsy in 28 patients and closed biopsy or aspiration cytology in the rest. Enneking stages IIA and IIB [7] were those most commonly encountered in malignant tumours, and all the 11 giant cell tumours and both aneurysmal bone cysts were aggressive (stage B 3) . Soft tissue encroachment was observed in 20 cases, and 25 patients presented with pathological fracture. The average length of lesion was 108.3 cm (range 50–210 cm).

Resection

Resection of the two aneurysmal bone cysts (stage B 3) and two angiofibromas (stage B 2) resulted in segmental defects that were large enough to warrant a mega-prosthetic replacement. Also the giant cell tumours were aggressive with extensive involvement of the entire proximal humerus, and hence even a marginal resection left us with a segmental loss that necessitated endoprosthetic reconstruction. Resection margins achieved were extra-articular and wide in 38 malignant sarcomas that were in stages IB, IIA or IIB; marginal in the rest of the tumours, including metastatic lesions.

Adjuvant treatment

Pre-operative chemotherapy was given to 19 patients with malignant tumours. Four patients (one giant cell tumour, 1 metastasis from prostate carcinoma and two cases of osteosarcoma) were referred to us after receiving preoperative radiotherapy. Two patients with giant cell tumour, one with chondrosarcoma and two with osteosarcoma had undergone prior excision or resection with inadequate margins. All patients with osteosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma and multiple myeloma received post-operative chemotherapy.

Reconstruction

The required dimensions of the prosthesis were estimated using X-rays in all patients. The material that was used to indigenously manufacture these prostheses was surgical stainless steel 316 L in 49 patients and titanium in 8 patients. Stainless steel wires or Dacron tapes were used for static suspension to secure the prosthesis proximally to the acromion process. The distal stem of the prosthesis was fixed with polymethylmethacrylate cement in the distal medullary canal (Fig. 2).

Follow- up radiograph of the patient in Fig. 1, after wide resection and custom mega-prosthetic replacement

Results

Patients were evaluated every 3 months during the first year and 6 monthly for the next 2 years with physical examination and plain radiography. Long-term follow up was annual. The average duration of follow-up was 5.5 years (range 2–14.5 years). One patient with osteosarcoma and one with aneurysmal bone cyst were lost to follow-up after 3.5 and 5 years respectively.

Complications

One patient had an intra-operative tear of the brachial artery that was repaired successfully with a saphenous venous graft. Two patients had post-operative radial nerve palsy that persisted even months after surgery. In one patient the distal humeral medullary canal splintered and was secured with stainless steel cerclage wiring until union was achieved.

Two patients developed deep wound infection that necessitated removal and revision in one patient after biological quiescence had been achieved. Operative debridement and appropriate antibiotics controlled the infection in the other, though his functional outcome was poor.

Mechanical complications included proximal migration of the prosthesis in six patients and aseptic loosening of the distal stem in two, requiring revision in both cases. Two prostheses, one made of stainless steel and the other of titanium, had to be revised following fracture of the humeral stem. Disassembly of the proximal stainless steel wires causing posterior dislocation was encountered in one patient.

Three patients with osteosarcoma and one with chondrosarcoma (stage IIB) had local recurrence after a mean period of 14.5 months. All four of these recurrent tumours were excised with wider margins. Two patients with osteosarcoma developed lung metastasis, of whom one died and the other was still alive at 53 months of follow-up, with an asymptomatic chest lesion that was detected at 42 months. Three patients with metastatic tumours and three with osteosarcoma died due to distant metastasis.

Functional outcome

As two patients were lost to follow-up, functional outcome was evaluated in 55 patients, using Enneking’s modified system of functional evaluation after surgical management of musculoskeletal tumours [6]. This system’s rating takes into account active range of movement at the shoulder, pain, stability, deformity, strength in shoulder abduction, functional activity and emotional acceptance. The maximum attainable abduction was 45°, chiefly by scapulo-thoracic movement. Rotations at the shoulder were restricted to a maximum of 15° in those patients who underwent wide resections that sacrificed the rotator cuff. Excellent functional outcomes were achieved in 18 patients, good in 25, giving a satisfactory function rate of 78%. Seven patients had a fair outcome, while the outcome in five patients was rated poor.

Oncological outcome

Of the 55 patients available at the latest follow-up, 43 were continuously disease-free and in 4 patients there was no evidence of disease following surgical management of local recurrence. One patient with osteosarcoma and another with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma were alive with disease, and six patients had died of disease (Table 1).

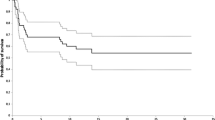

Survivorship analysis

Survival analysis was carried out using the Kaplan–Meier survivorship method, taking death as end point for patient survival and mechanical failure, revision or both as end point for prosthesis survival. Prosthetic survival rates were calculated for all the patients (Fig. 3) and were 94.5% and 83% at 5 and 10 years respectively. Five-year survival rate computed for 34 patients (Fig. 4) with proximal humeral primary sarcomas was 83.2%.

Discussion

Reconstruction of proximal humerus after tumour resection with autogenous grafts, osteoarticular allografts, prosthetic replacements, allograft–prosthetic composites and autograft–prosthetic composites have all been described in the literature [1–3, 20, 24]. Each of these methods has been the subject of extensive discussion, and each presents unique problems. Endoprosthetic replacement of proximal humerus with modular or customized prostheses is a safe, realistic and reliable [13, 19, 25] option that offers the lowest complication rates [19] and immediate stability for aggressive recovery of active shoulder movement, which facilitates normal functioning of the elbow and hand [16].

A relatively favourable region for reconstruction of large segments after resection of musculoskeletal tumours [13], proximal humeral endoprosthetic replacement is still a major challenge, in terms of both oncological cure and limitation of functional handicap [3], that needs to be addressed.

Achieving disease-free margins should be the prime concern in malignant lesions. However, extra-articular wide resections of high-grade extra-compartmental lesions sacrifice the rotator cuff or the abductor mechanism, so that osteoarticular allografts cannot be recommended [9]. Moreover, the high rates of complications [12] such as joint instability, fracture, transmission of infection [22], non-union and rejection that are observed with osteoarticular allografts preclude [10] such a choice for proximal humeral tumours.

The local recurrence rate of 7% of our series is comparable to that found by Malawer et al. [11, 13], who reported a lower recurrence rate (2 of 29 patients) for the proximal humerus than for all other sites. Wittig et al. [25] recorded no recurrences in a 10-year follow-up of extra-articular resections in 22 patients with high-grade osteosarcoma of the proximal humerus, reconstructed by cemented endoprosthetic replacement.

The two deep infections that we encountered were in giant cell tumours, of which one had had undergone prior excision and bone grafting. This infection rate of 3.5% is equivalent to those found in other similar series by Fuhrmann et al. [8] and Malawer et al. [11, 13] and superior to those reported in osteoarticular allograft series by O’Connor et al. [15] and Gebhardt et al. [9] who stated rates of 9% and 15% respectively.

As regards giant cell tumours, although endoprosthetic replacement may not be the first line of treatment, resection of large and histological aggressive tumours may necessitate reconstruction, whereby endoprosthesis has proven to be a viable option. The present authors have used endoprosthetic replacement for 11 of the 16 patients with highly aggressive proximal humeral giant cell tumours treated in their institution.

With improving overall and disease-free survival rates (78% in our series), tumoral resections call for a durable reconstructive option as most of the patients are young. Unrestricted motion cannot be realized with any method of reconstruction after resections that excise part or all of the deltoid or the rotator cuff. The most important mechanical complication of proximal humeral endoprosthesis [8] is a proximal subluxation of the head, painfully impinging on the subacromial arch. Such complications met with in six of our patients were moderate, causing partial disability and restriction of all movements at the joint, lowering the acceptance levels. This eventually affected the function in all six cases, resulting in a fair or poor rating. All of these six patients refused revision surgery. They underwent extensive soft tissue resection, compromising the stability of the joint. Use of Dacron tapes as part of the primary procedure was inadequate to provide optimal stability and function. Although we did not employ any net or mesh to prevent such a complication, their use may be beneficial in such patients.

The decline in the prosthetic survival rate from 94.5% at 5 years to 88.3% at 10 years with a revision rate of 8.7% cannot be attributed to one single factor. Future studies need to focus on modifying prosthetic design [14, 18] and materials to reduce proximal migration, fracture and aseptic loosening of the humeral stem. Component sizes and design should be guided by an in-depth understanding of the variations in proximal humeral morphology, especially when the normal anatomy is distorted. Even so, these survival rates indicate a mechanical and functional advantage over allograft arthrodesis [15, 17].

The long-term oncological results depend largely on the stage of disease and the quality of resection. A reconstructive option that is employed after careful patient selection and pre-operative counselling with regard to the limitations eventually improves the post-operative acceptance levels. Custom mega-prosthetic replacement is an interesting therapeutic option with limited complication rates, giving a useful functional limb compared to other forms of reconstruction.

References

Asavamongkolkul A, Eckardt JJ, Eilber FR, Dorey FJ, Ward KG, Kelly CM, Wiraganowicz PZ, Kabo JM (1999) Endoprosthetic reconstruction for malignant upper extremity tumors. Clin Orthop Relat Res 360:207–220

Bos G, Sim F, Pritchard D, Shives T, Rock M, Askew L, Chao E (1987) Prosthetic replacement of the proximal humerus. Clin Orthop Relat Res 224:178–191

De Wilde LF, Van Ovost E, Uyttendaele D, Verdonk R (2002) Results of an inverted shoulder prosthesis after resection for tumor of the proximal humerus. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 88:373–378

Eckhardt, JJ, Eilber FR, Dorey FJ, Mirra JM (1985) The UCLA experience in limb salvage surgery for malignant tumors. Orthopedics 8:612–621

Enneking WF (1983) Musculoskeletal tumor surgery, vol.1. Churchill Livingstone, New York, pp 378–405

Enneking WF (1987) Modification of the system for functional evaluation of surgical management of musculoskeletal tumors. In Bristol–Myers/Zimmer Orthopaedic Symposium. Limb salvage in musculoskeletal oncology. Churchill Livingstone, New York, pp 626–639

Enneking WF, Spanier SS, Goodman MA (1980) A system for the surgical staging of musculoskeletal sarcomas. Clin Orthop 153:106–120

Fuhrmann RA, Roth A, Venbrocks RA (2000) Salvage of the upper extremity in cases of tumorous destruction of the proximal humerus. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 126:337–344

Gebhardt MC, Roth YF, Mankin HJ (1990) Osteoarticular allografts for reconstruction in the proximal part of the humerus after excision of a musculoskeletal tumor. J Bone Joint Surg Am 72:334–345

Getty PJ, Peabody TD (1999) Complications and functional outcomes of reconstruction with an osteoarticular allograft after intra-articular resection of the proximal aspect of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Am 81:1138–1146

Jensen KL, Johnston JO (1995) Proximal humeral reconstruction after excision of a primary sarcoma. Clin Orthop 311:164–175

Lord CF, Gebhardt MC, Tomford WW, Mankin HJ (1988) Infection in bone allografts—incidence, nature, and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am 70: 369–376

Malawer MM, Chou LB (1995) Prosthetic survival and clinical results with use of large-segment replacements in the treatment of high-grade bone sarcomas. J Bone Joint Surg Am 77:1154–1165

Michael PL, Sam Kurutz BS (1999) Geometric analysis of commonly used prosthetic systems for proximal humeral replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 81:660–671

O’Connor MI, Sim FH, Edmund YS Chao (1996) Limb salvage for neoplasms of the shoulder girdle. Intermediate reconstructive and functional results. J Bone Joint Surg Am 78:1872–1888

Olsson E, Andersson D, Brostrom LA, Wallensten R, Nilsonne U (1990) Shoulder function after prosthetic replacement of the proximal humerus. Ann Chir Gynaecol 79:157–160

Peabody TD, Finn HA, Simon MA (1991) Allograft arthrodesis of the shoulder after extra-articular resection of malignant tumors of the proximal humerus. In: Brown KLB (ed) Complications of limb salvage. Prevention, management and outcome. International Symposium on Limb Salvage, Montreal, pp 589–592

Robertson DD, Yuan J, Bigliani LU, Flatow EL, Yamaguchi K (2000) Three-dimensional analysis of the proximal part of the humerus: relevance to arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 82:1594–1602

Rodl RW, Gosheger G, Gebert C, Lindner N, Ozaki T, Winkelmann W (2002) Reconstruction of proximal humerus after wide resection of tumors. J Bone Joint Surg Br 84:1004–1008

Shin KH, Park HJ, Yoo JH, Hahn SB (2000) Reconstructive surgery in primary malignant and aggressive benign bone tumor of the proximal humerus. Yonsei Med J 41:304–311

Simon M (1989) Limb-salvage for osteosarcoma. In: Yamamuro T (ed) New developments for limb salvage in musculoskeletal tumors. Springer, New York, pp 71–72

Tomford WW (1995) Current concepts review. Transmission of disease through transplantation of musculoskeletal allografts. J Bone Joint Surg Am 77:1742–1754

Tomita K, Aotake Y, Sugihara M, Tsuchiya H (1989) Overall results and functional evaluation of limb salvage for osteosarcoma. In: Yamamuro T (ed) New developments for limb salvage in musculoskeletal tumors. Springer, New York, pp 53–57

Wada T, Usui M, Isu K, Yamawakii S, Ishii S (1999) Reconstruction and limb salvage after resection of malignant bone tumor of the proximal humerus—a sling procedure using free vascularised fibular graft. J Bone Joint Surg Br 81:808–813

Wittig JC, Bickels J, Lellar-Graney KL, Kim FH, Malawer MM (2002) Osteosarcoma of the proximal humerus: long-term results with limb sparing surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res 397:156–176

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mayilvahanan, N., Paraskumar, M., Sivaseelam, A. et al. Custom mega-prosthetic replacement for proximal humeral tumours. International Orthopaedics (SICO 30, 158–162 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-005-0029-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-005-0029-z