Abstract

A 2-year-old girl presented with severe abdominal pain due to a giant iliac artery aneurysm. We embolized the internal iliac artery with microcoils and then eliminated the aneurysmal sac using a BeGraft peripheral stent without any complications. To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous reports of a transcatheter giant iliac artery intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Iliac artery aneurysms are very rare in children. There are no data regarding the frequency of these aneurysms; only a few case reports have been published [1,2,3]. The greater the diameter of the aneurysm is, the higher the risk of rupture, which is life threatening. Symptoms usually occur due to the compression of surrounding tissues. In adults, treatment entails surgical or endovascular repair [4]. Our case involved a 2-year-old patient with a giant symptomatic iliac artery aneurysm that was successfully treated by the transcatheter approach with a BeGraft peripheral stent. This is the first case presented in the literature.

Case Report

A 2-year-old patient was examined for abdominal pain and was referred to our clinic upon detection of a giant aneurysm in the left iliac artery. The physical examination revealed a painful pulsatile mass in the left lower quadrant. No etiological factor was found in the rheumatologic tests, and trauma etiology was not detected from the anamnesis. The infection parameters were negative. She had a history of long-term neonatal intensive care due to prematurity, but an umbilical artery catheter had not been inserted.

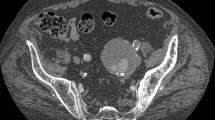

Abdominal ultrasonography revealed a pulsatile mass in the left umbilical quadrant, and a three-dimensional computerized angiography showed that the iliac artery aneurysm was isolated (Fig. 1). The gigantic aneurysm was seen extending from the left common iliac artery to the femoral artery along the external iliac artery, and the internal iliac artery originated from the aneurysm.

A transcatheter intervention was planned because of the risk of surgery. A 5F sheath was placed in both femoral arteries. As seen by imaging after the injection of contrast material, the widest part of the aneurysm was 26.4 mm, and the length of the aneurysm was 36 mm (Fig. 2a). The left internal iliac artery was then embolized with four platinum 18-2-2 Hilal embolization microcoils (Cook, Bloomington, IN, USA) due to the risk of retrograde filling from the potential collateral circulation (Fig. 2b). A 6F long sheath was advanced from the left femoral artery to the iliac bifurcation. The peripheral BeGraft 6 × 58-mm covered stent (Bentley InnoMed, Hechingen, Germany) was extended from the iliac bifurcation to the peripheral iliac artery and was inflated at an atmospheric pressure of 9. As seen from the control injection, iliac artery patency was achieved, and there was no leakage into the aneurysmal sac (Fig. 2c, d).

a The extension and tortuosity of the left external iliac artery aneurysm from the common iliac artery to the external iliac artery were imaged after the injection of contrast material. b Microcoil embolizations of the internal iliac artery through the aneurysmal sac to prevent retrograde filling. c, d After the placement of the peripheral BeGraft-covered stent, the aneurysmal sac was eliminated, and the flow provided patency

After the procedure, clopidogrel and aspirin tablets were started at antiplatelet doses; clopidogrel was discontinued when the skin demonstrated mild, focal bleeding 1 month later. Both intrastent blood flow and femoral artery flow were monitored without any problems by monthly Doppler ultrasonography in the 8-month follow-up.

Discussion

In children, iliac artery aneurysms are usually caused by infection, collagen tissue disease, trauma, or arthritis. Primary iliac artery aneurysms are very rare. Moreover, iliac artery aneurysms are rarely observed in older patients with isolated or abdominal aortic aneurysms. Surgical treatment can be difficult due to patient age, aneurysm size, and native vessel diameter [1,2,3]. Even if the patient has no symptoms, treatment should be performed urgently because of the risk of rupture and peripheral embolization [4]. In addition, after surgery, long-term continuity of the graft material should be ensured. Femoral veins can be successfully used as interposition grafts in bilateral isolated iliac artery aneurysms in children aged 3 years; however, this approach may carry the risk of peripheral edema and circulatory disorders [3]. No pediatric transcatheter treatment has been reported in the literature thus far. Endovascular treatment seems to be possible; it was successful in our case with careful intervention and the use of appropriate equipment. The small diameter of the delivery sheath of the BeGraft-covered stent represents an important advantage for pediatric patients. However, the peripheral aortic BeGraft stent can be dilated up to a diameter of 8 mm in subsequent procedures. This diameter is unlikely to cause a clinical problem in adult women since the iliac artery has an average diameter of 9 mm.

Coil embolization of the proximal initiation of the internal iliac artery can both prevent retrograde collateral circulation of the aneurysm sac and facilitate access of the contralateral circulation to end organs via the collaterals. This may lead to patient buttock claudication, epigastric ischemic pain, and decreased reproductive organ blood supply [4].

There is no difference in the patency of the iliac artery or the mortality risk in adults between endovascular and surgical treatment; however, endovascular treatment has a significant advantage in terms of decreasing morbidity [4]. We believe that in the pediatric age group, the reductions in both morbidity and mortality are considerable with transcatheter treatment. Pediatric treatment without a transcatheter has been reported in the literature. It is possible to perform a careful endovascular intervention with the use of appropriate equipment, as in our case, for the treatment of iliac artery aneurysms.

Long-term follow-up is necessary for these patients due to the need to monitor the continuity of stent flow, the possibility of stent predilatation, and the risk of new aneurysms.

References

Lee JH, Oh C, Youn JK et al (2016) Right iliac arterial aneurysm in a 4-year-old girl who does not have a right external iliac artery. Ann Surg Treat Res 91:265–268

Krysiak R, Zylkowski J, Jaworski M et al (2019) Neonatal idiopathic aneurysm of the common iliac artery. J Vasc Surg Cases Innov Tech 5:75–77

Chithra R, Sundar RA, Velladuraichi B et al (2013) Pediatric isolated bilateral iliac aneurysm. J Vasc Surg 58:215–216

Kirkwood ML (2019) Surgical and endovascular repair of iliac artery aneurysm. UpToDate, Waltham, MA

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethical committee.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Başpınar, O., Vuruşkan, E., Coşkun, S. et al. Transcatheter Treatment of a Symptomatic Giant Iliac Artery Aneurysm with a BeGraft Peripheral Stent in a 2-Year-Old Child. Pediatr Cardiol 41, 1067–1070 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-019-02266-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-019-02266-1