Abstract

Apicomplexan parasites cause serious illnesses, including malaria, in humans and domestic animals. The presence of apicortins is predominantly characteristic of this phylum. All the apicomplexan species sequenced contain an apicortin which unites two conserved domains: DCX and partial p25alpha. This paper identifies novel apicortin orthologs in silico and corrects in several cases the erroneous sequences of hypothetical apicortin proteins of Cryptosporidium, Eimeria, and Theileria genera published in databases. Plasmodium apicortins, except from Plasmodium gallinaceum, differ significantly from the other apicomplexan apicortins. The feature of this ortholog suggests that only orthologs of Plasmodiums hosted by mammals altered significantly. The free-living Chromerida, Chromera velia, and Vitrella brassicaformis, contain three paralogs. Their apicomplexan-type and nonapicomplexan-type apicortins might be “outparalogs.” The fungal ortholog, Rozella allomycis, found at protein level, and the algal Nitella mirabilis, found as Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly (TSA), are similar to the known Opisthokont (Trichoplax adhaerens, Spizellomyces punctatus) and Viridiplantae (Nicotiana tabacum) ones, since they do not contain the long, unstructured N-terminal part present in apicomplexan apicortins. A few eumetazoan animals possess apicortin-like (partial) sequences at TSA level, which may be either contaminations or the result of horizontal gene transfer; in some cases the contamination has been proved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Apicomplexan parasites (e.g., Toxoplasma and Plasmodium) cause serious illnesses in humans and domestic animals. Species in the genus Plasmodium cause malaria from which over 1 million people die each year. Other members of the phylum Apicomplexa are responsible for animal sicknesses such as coccidiosis and babesiosis resulting in significant economic burden for animal husbandry.

A new protein, termed apicortin, has recently been identified and thought to occur only in apicomplexans and in the placozoan animal Trichoplax adhaerens (Orosz 2009). Apicortins unite two conserved domains, a DCX motif and a partial p25alpha sequence, which are separately found in other proteins, in doublecortins and TPPPs (Tubulin Polymerization Promoting Proteins), respectively (Orosz 2009). The DCX (doublecortin) domain (Pfam03607, IPR003533) is named after the brain-specific X-linked gene doublecortin (Sapir et al. 2000). The whole p25alpha domain (Pfam05517 or IPR008907) of 140–160 aa length occurs in the members of the TPPP protein family (Orosz 2012; Ovádi and Orosz 2009; Vincze et al. 2006). It is not a structural domain but was generated automatically based on sequence alignment from Prodom 2004.1 for the Pfam-B database (http://www.sanger.ac.uk//cgi-bin/Pfam/getacc?PF05517). The partial p25alpha domain, a 30–32 aa long sequence, occurs independently from the other parts of the p25alpha domain as well, mostly but not exclusively in protists (Orosz 2012). The function of apicortins is unknown; however, both the p25alpha and DCX domains play an important role in the stabilization of microtubules (Hlavanda et al. 2002; Tirián et al. 2003; Sapir et al. 2000; Kim et al. 2003), which suggests a similar role for apicortin.

Apicortin received its name on the basis of its occurrence (Apicomplexa) and one of its characteristic domains (doublecortin). Genomes and sequence data, which have become recently available, show that apicortin is, indeed, a characteristic protein of the phylum of Apicomplexa. It is present in the genomes of all currently sequenced apicomplexan parasites (Babesia bovis, Cryptosporidium spp., Eimeria tenella, Plasmodium spp., Theileria spp., Toxoplasma gondii, Neospora caninum) (Orosz 2009, 2011). Proteins of the Plasmodium genus differ somewhat from the other apicortins since they lack a very characteristic Rossman-like sequence, GXGXGXXGR. Apicortin is one of the most abundant proteins of the placozoan animal, T. adhaerens (Ringrose et al. 2013). Otherwise its occurrence is very limited; it has only been identified in the chytrid fungus, Spizellomyces punctatus (Orosz 2011). New genomes and sequence data suggest that its phylogenetic distribution is probably wider than thought previously.

Methods

Database Homology Search

Accession numbers of protein and nucleotide sequences refer to the NCBI GenBank database, except if otherwise stated. The database search was started with an NCBI blast search. The queries were sequences of apicortins of various phylogenetic groups (T. adhaerens, fungi, various apicomplexan families) and if a new apicortin was found which belonged to a new phylogenetic group, its sequence was used also as a query. BLASTP and TBLASTN analyses (Altschul et al. 1997) were performed on protein and nucleotide sequences available at the NCBI website, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/. Additional search was carried out at specific apicomplexan web sites, GeneDB, ApiDB, CryptoDB, PiroplasmaDB, ToxoDB, and PlasmoDB (Aurrecoechea et al. 2007, 2009; Gajria et al. 2008; Heiges et al. 2006; Hertz-Fowler et al. 2004; http://www.genedb.org/; http://eupathdb.org/eupathdb/). Nucleotide sequences identified in BLASTN searches were translated in the reading frames denoted in the BLASTN hit, taking frame shifts or introns of genomic sequences into account. Orthology was established if three criteria were fulfilled: the BLAST E-score was lower than 1e-5; the query and the hit were reciprocal best-hits and the new protein/nucleotide contained both the partial p25alpha and DCX domains. The European Bioinformatics Institute InterPro (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/) (Hunter et al. 2009), the Pfam protein families (http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/) (Finn et al. 2008) and the CDD (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/cdd.shtml) (Marchler-Bauer et al. 2007) databases were checked for proteins possessing both DCX and partial p25alpha domains not detected by BLAST.

Phylogenetic Analysis

Multiple alignments of sequences were carried out by the Clustal Omega program (Sievers et al. 2011). Multiple sequence alignment used for constructing phylogenetic trees is shown in Online Resource 1. Bayesian analysis was performed using MrBayes v3.1.2 (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck 2003). Default priors and the WAG model (Whelan and Goldman 2001) were used assuming equal rates across sites. Two independent analyses were run with three heated and one cold chains (temperature parameter 0.2) for 3 × 106 generations, with a sampling frequency of 0.01 and the first 25 % of the generations were discarded as burn-in. The two runs converged in all cases. The tree was drawn using the program Drawgram.

The Phylip package version 3.696 (Felsenstein 2008) was used to build the Maximum Likelihood (ML) phylogenetic trees with bootstrap values. One thousand datasets were generated using the program Seqboot from the original data, i.e., the multiple alignments done by Clustal Omega. This was followed by running the program Proml (Protein Maximum Likelihood) on each of the datasets in the group, using the JTT (Jones–Taylor–Thornton) model (Jones et al. 1992). A consensus tree (from all the 1000 trees) was generated using the program Consense. The trees were drawn using the program Drawgram.

Prediction of Unstructured Regions

Sequences were submitted to the IUPRED server freely available at http://iupred.enzim.hu/ (Dosztányi et al. 2005), in the “long disorder” mode. Sequences were also submitted to the VSL2B server optimized for proteins containing both structure and disorder (Obradovic et al. 2005) and freely available at http://www.dabi.temple.edu/disprot/predictorVSL2.php.

Results and Discussion

Identification of New Apicortins

BLASTP and TBLASTN analyses (Altschul et al. 1997) were performed on protein and nucleotide sequences available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (USA) and other websites (cf. Methods) using the sequences of placozoan, fungal and apicomplexan apicortins as queries. Since apicortins contain two different domains thus various domain databases were also checked for proteins possessing both the DCX and the partial p25alpha domains not detected by BLAST. The results of the search, i.e., the new (hypothetical) apicortins not known before, are listed in Table 1 and the sequences in Online Resource 2.

Protist Apicortins

Apicortins of Apicomplexa

Most of the novel findings are, not surprisingly, apicomplexan proteins and sometimes nucleotides. All the apicomplexan species, belonging either to Aconoidasida or Conoidasida, seem to contain apicortin. It is true for the recently sequenced Plasmodium, Babesia, Theileria, and Eimeria species, similarly to their orthologs, which were known and listed earlier (Orosz 2009, 2011). Besides them, new species of Conoidasida, namely Cyclospora cayetanensis, Hammondia hammondi, Sarcocystis neurona, Ascogregarina taiwanensis, and Gregarina niphandrodes, have been identified as apicortin-possessing ones. Most of the new apicortins are hypothetical proteins.

Apicortins of Chromerida

Both of the recently discovered chromerids, Chromera velia (Moore et al. 2008) and Vitrella brassicaformis (Oborník et al. 2012), closely related to Apicomplexa, contain three apicortins; two paralogs of both species are more similar to each other than to the third one.

Nonprotist Apicortins

Apicortins of Fungi

Besides the known S. punctatus (Orosz 2011), another fungus, the Cryptomycota Rozella allomycis, has been found to contain an apicortin protein (EPZ32946). The parasitic genus Rozella forms the deepest branching clade of fungi (Lara et al. 2010) and is mostly known to parasitize water molds. R. allomycis itself is an obligate parasite of the Blastocladiomycotan fungus Allomyces. Both S. punctatus and R. allomycis possess a flagellum. There is a strong correlation between the presence of the p25alpha domain and that of the eukaryotic cilium/flagellum (Orosz and Ovádi 2008). The vast majority of Fungi lost the flagellum (Liu et al. 2006), and, indeed, both apicortin and TPPP can be found exclusively in flagellated fungi (Blastocladiomycota, Chytridiomycota, Cryptomycota).

Animal Apicortins?

Until now only one early branching animal, T. adhaerens, was known to contain apicortin (Orosz 2009; Ringrose et al. 2013). Surprisingly, some animals seem to possess apicortin-like sequences which can be identified at TSA level. Only an insect, Aleochara curtula, contains the whole sequence. TSAs of Machilis hrabei and Teleopsis dalmanni lack the N-terminus, similarly to a TSA from the crustacean Caligus rogercresseyi. These hiatuses are consequences of the incomplete sequencing data, however, TSAs lacking the whole N-terminal part, including the p25alpha domain, cannot be considered as apicortins until the whole sequences are not established. Finally, although a TSA of Apostichopus japonicus also lacks a significant part of the N-terminus, but this Echinodermata possesses apicortin since the established sequence contains enough amino acids to recognize it.

Apicortins of Viridiplantae

A complete apicortin was found as TSA in Nitella mirabilis and a partial one in Salicornia europaea. These findings have great significance since only a Nicotiana tabacum EST sequence was known earlier as plant apicortin (Orosz 2011). Moreover, the partial sequence of S. europaea, a close relative of N. tabacum, is practically identical with the corresponding part of the tobacco sequence but differs significantly from that of the algal N. mirabilis. It suggests that these hits are real ones and not due to some kind of contamination.

Correction of Published Apicortin Sequences

In certain cases, due to the shortcomings of sequencing, some parts of apicomplexan apicortins cannot be established (cf. Online Resource 2). In another cases, the sequences of hypothetical proteins published in databases should be corrected. They include both recently identified and previously known sequences. The reason for the incorrect sequences is in each case that the exon boundaries were not recognized properly. The corrections can be made by comparing the sequences of apicortins belonging to the same genus (Cryptosporidium, Eimeria, Theileria), as well as by comparing protein sequences with WGS nucleotide ones based on the conservative exon–intron structure of closely related apicortins. A detailed example is given for Eimeria acervulina apicortin in Online Resource 3. All the corrections are listed in Online Resource 4.

Apicortins belonging to various genera are characterized by specific intron–exon structures that are partly conserved among them (Fig. 1). The most conserved exon boundary, which is present in apicortins of T. adhaerens, fungi, Chromerida, all Coccidia (Eimeriadae and Sarcocystidae) and A. taiwanensis but is missing from all Aconoidasida (Plasmodium, Theileria, Babesia) and Cryptosporidium, is in the middle of the partial p25alpha domain. (This exon starts in each case with a glycine which is conserved even in apicortins not possessing this exon boundary). There are three further boundaries which are present in more than one genus; while Coccidia species have the most, six, exons. Interestingly, A. taiwanensis has an almost similar exon–intron structure as that of Coccidia. Theileria, Babesia, and Cryptosporidium apicortins lost 2, 3, and 4 introns, respectively (Table 1). Plasmodium apicortin genes generally do not contain introns except the members of the Laverania and Haemamoeba subgenus, where the first 15–20 amino acids of the N-terminal part, similarly to the vast majority of the apicomplexan apicortins, i.e., Coccidia and Piroplasmida, are coded by a separate exon.

Domain end exon structure of apicortins. Gray shading labels the partial p25alpha and the DCX domains. Stripes show the position of the Mss4-like domain in Plasmodium falciparum according to the InterPro Database. The start of the exons and their first amino acids are indicated. Italic and underlined amino acids are encoded by nucleotides of two exons. Dashed lines in Rozella allomycis show that its sequence after the partial p25alpha domain continues at the amino acid A30. The question mark in Ascogregarina taiwanensis apicortin shows that the last part of its sequence is missing

Characterization of the Regions of the Apicortins

The various apicortins can be classified into two main groups according to their structure: apicomplexan ones, without exception, possess a long, unstructured N-terminal part, while nonapicomplexan ones lack it. It was suggested that it is an “innovation” of this phylum that can play a functional role in protein–protein complex formation (Orosz 2011) and may be in connection with the parasite–host interactions. (Here I note that the N-terminus of the newly identified apicomplexan apicortins is also predicted to be disordered—cf. Fig. 2). Interestingly, their free-living Chromerida “cousins” seem to possess apicortins lacking this part, which is in accordance with this hypothesis. (In fact, Cvel_6797 of C. velia has an N-terminal part, which is significantly shorter than those of the apicomplexan apicortins but longer than those of other orthologs).

Disorder prediction of Eimeria mitis apicortin by VSL2B (solid line) and IUPRED (dotted line) predictors. Disorder prediction values for the given residues are plotted against the amino acid residue number. The significance threshold, above which a residue is considered to be disordered, set to 0.5, is shown. The polyglutamine sequence, the partial p25alpha, and DCX domains are indicated by bold lines at the bottom of the plot

The long disordered N-terminal part of these proteins is not conserved among the species belonging to different genus; and not even among the proteins of the various subgenera of Plasmodium spp. In the case of Plasmodium orthologs, this part of the proteins of the rodent (Vinckeia) and primate (Plasmodium) parasites is rather different, and in Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium reichowi (Laverania group) apicortins this part is even more distinct as well as in the only sequenced avian parasite, Plasmodium gallinaceum (Haemamoeba subgenus). It is known that unstructured regions usually evolve faster than structured ones since they are more tolerant to mutations (Chen et al. 2006). Additionally, the rapid evolution of these disordered regions may provide adaptive benefits (Feng et al. 2006), which can be important in their interactions.

P. falciparum and P. reichowi have a further speciality as well: according to the InterPro database (Hunter et al. 2009), their N-terminal part also contains an Mss4-like domain (IPR011057) (Fig. 3). It is a ubiquitously occurring domain which was named after Mss4, a conserved accessory factor for Rab GTPases, functioning as ubiquitous regulators of intracellular membrane trafficking (Zhu et al. 2001). Mss4 itself has a complex fold consisting of several coiled beta-sheets, and it involves a duplication of tandem repeats of two similar structural motifs. It contains a zinc-binding site as well. However, none of these characteristics can be found in these Plasmodium apicortins.

Multiple sequence alignment of apicortins by Clustal Omega. In general, apicortins of only one species per genus are shown. Amino acids, which are identical and biochemically similar in the majority of the proteins, are indicated by black and gray shading, respectively. The letters x and o label the partial p25alpha and the DCX domains, respectively. The N- and C-terminal ends are not shown

All the Eimeria apicortins contain in the N-terminal end a polyglutamine sequence with a length of 6–18 amino acids. Eimeria protein-coding sequences are known to be extremely rich in homopolymeric amino acid repeats (HAARs), the extent of which is greater in Eimeria than in any other organism sequenced to date (Reid et al. 2014). The most common repeat in Eimeria genus is the trinucleotide CAG, which occurs mostly in coding sequences, and encodes preferentially alanine or glutamine. HAARs of this type, encoding strings of at least seven amino acids, were found in 57 % of E. tenella genes. Reid et al. (2014) found that glutamine HAARs occurred mainly in regions with medium to high solvent accessibility. Due to the glutamine repeats, the N-terminus of the Eimeria apicortins is predicted to be disordered with the highest, near 100 %, probability, which provides, indeed, high solvent accessibility. The disorder prediction plot of E. mitis shows a typical apicortin profile (Orosz 2011): a long disordered N-terminus, with the highest disorder tendency at the polyglutamine sequence, a disordered interdomain linker and a highly ordered DCX domain (Fig. 2).

Apart from the differences in the N-terminus, the sequences are similar in general, concerning both the first and the second domains and the interdomain part (Fig. 3). In the partial p25alpha domain, there are two kinds of notable differences. First, this part of the N. tabacum EST sequence lacks a few, otherwise conserved amino acids. Second, and most importantly, proteins of the Plasmodium genus and that of the fungus, R. allomycis lack the final part of this domain, the very characteristic Rossman-like sequence, GXGXGXXGR, thus the presence of the partial p25alpha domain is hardly recognizable. However, the first member of the Haemamoeba subgenus of the Plasmodium genus, P. gallinaceum, the sequencing of the genome of which has been in progress, contains an apicortin and its sequence differs significantly from those of the other Plasmodium species and is more similar to the other apicomplexan apicortins. It contains the whole partial p25alpha domain, including the Rossman-like sequence as well. This fact suggests that originally Plasmodium apicortins were more similar to the other orthologs than today.

Otherwise, the sequences are very similar, independently whether the protein belongs to the Apicomplexa or not. The same statement is valid for the interdomain part as well except in the case of the fungi orthologs. The S. punctatus protein is more different in this part than the other orthologs, while in the R. allomycis apicortin the linker region is limited only for a few amino acids. The first part of this region of Plasmodium proteins, except that of P. gallinaceum, also differs somewhat from those of the other apicomplexan orthologs. The interdomain parts were predicted to contain a short disordered segment, suggesting that it functions as a flexible linker between the two domains (Orosz 2011).

In the DCX domain, there is overall similarity between the two groups (apicomplexans and others); there is no exception: the similarity occurs through the whole domain in all orthologs. Finally, apicortins contain a short C-terminal tail.

Phylogenetic Considerations

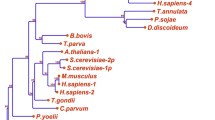

Phylogenetic tree of apicortins was constructed by Bayesian and by ML analysis as well using S. punctatus apicortin as an outgroup (Fig. 4). The amino acids of the very long and different N-termini and those of the short C-termini were omitted from the multiple sequence alignment which served as a basis for the analysis. As I mentioned, in some cases the database sequences had to be corrected. Not fully sequenced apicortins were not considered except from A. taiwanensis since only two sequences of gregarines have been established. The trees somewhat differ from each other and correspond to the species phylogeny in the most cases. Common characteristics of both trees are that apicomplexan and nonapicomplexan apicortins are generally clustered separately. We should remember that only apicomplexan ones possess the disordered N-terminus, which part was not taken into account at the construction of the trees.

Phylogenetic tree of apicortins. The numbers at the nodes represent Bayesian posterior probability values and Maximum Likelihood (ML) bootstrap values calculated from 1000 replicates shown only for the main branches of the tree. The label “-” indicates that the branch was not supported by the ML analysis. Species belonging to Apicomplexa are labeled by black, to Chromerida by red, to Opisthokonta (animals, fungi) by blue, to Viridiplantae (plants, green algae) by green color (Color figure online)

Apicomplexan Apicortins

All the various apicomplexan families, i.e., Babesiidae, Theileriidae, Eimeriidae, Sarcocistidae, Cryptosporiidae, form separated clades as well as Plasmodiidae. Both Gregarinidae and Lecudinidae are represented only with one species. Within Plasmodium, the various subgenera (Vinckeia, Laverania, Plasmodium, Haemamoeba) constitute also separate clades. The relative positions of the families in the Bayesian tree correspond to the species phylogeny (e.g., Barta and Thomson 2006; Templeton et al. 2010) in the most cases. Gregarinasina are considered as the most “archaic” apicomplexan group branching at the base of the phylum (Leander 2008; Templeton et al. 2010). Indeed, A. taiwanensis and G. niphandrodes apicortins are at the base of the apicomplexan clade. Plasmodiums are sisters to Piroplasmida (Theileriadae and Babesiadae) and they are sisters to Coccidia (Eimeriadae and Sarcocystidae). Theileriadea and Babesiadae, and Eimeriadae and Sarcocystidae, respectively, are sisters to each other. However, Cryptosporidium are within Piroplasmida, which does not meet the expectation. Of course, it does not over-write the accepted species phylogeny since a tree from a single molecular sequence represents only the phylogeny of that gene. It should be noted that due to the biased taxon sampling the evaluation of the correct phylogenetic relationship is not an easy task; e.g., the very careful Bayesian analysis carried out by Morrison (2009) never placed the Haemosporidia (including Plasmodium) with the Piroplasmida, which is their traditionally expected location. In contrast to the Bayesian tree, in the ML tree the mutual positions of the various apicomplexan families are not resolved.

Nonapicomplexan Apicortins

The few apicortins of Opisthokonta and Viridiplantae are well separated from those of the Apicomplexa and Chromerida except the tentative animal apicortin, A. curtula identified as TSA, which can be found within the Apicomplexa clade. It is placed with G. niphandrodes apicortin with maximal probability. Since gregarines are parasites of invertebrates, including insects, it would be possible that this insect TSA is present due to contamination. This suggestion is supported by BLASTX search, using this TSA as query, which gives two kinds of hits, corresponding to its two halves: one is an apicortin of various apicomplexan species; the best one is from G. niphandrodes (XP_011128898; e-value: 1-e76); the other one is a hypothetical protein with unknown function from G. niphandrodes (XP_011131420; e-value: 4-e26) (Online resource 5). This latter protein has been found only in this species and does not possess any ortholog at all. The contamination might be valid for the other apicortin-like TSAs of animal origin, which do not have the complete sequence, including A. japonicus (Japanese see cucumber), an echinodermata. See cucumbers (class Holothuroidea) host archigregarines as well; e.g., Leptosynapta clarki is parasitized by Veloxidium leptosynapte (Wakeman and Leander 2012). Another answer would be a horizontal gene transfer between the parasites and their hosts. However, the choice between these alternatives is difficult, since the sequences are rather different from those of the known gregarine apicortins and do not possess the specific N-terminal part. If complete archigregarine sequences were known the answer would be possible.

Here I should mention that sometimes the contamination of the genomic sequences available in databases is evident. The WGS of Colinus virginianus, a bird, contains a sequence which is very similar to the apicortins of the Sarcocystidae, T. gondii, N. caninum and H. hammondi and shows 91 % identity to a WGS sequence of S. neurona. However, as it was shown elsewhere (Orosz 2015), the published genome of C. virginianus is contaminated by a not-yet-identified Sarcocystis species; e.g., it contains the significant part of the apicomplexan organelle, apicoplast. Similarly, the Rhipicephalus microplus TC356 mRNA sequence (GenBank: JT844686.1) (Heekin et al. 2012) is a contamination from B. bovis. The sequence is identical with that of the B. bovis apicortin coding sequence although the first part, coding 75 amino acids, is missing (Online Resource 6).

Chromerid Apicortins

The recently identified two chromerids, C. velia and V. brassicaformis, are the only species which contain three apicortins. These photosynthetic algae are closely related to apicomplexan parasites and share various morphological and molecular characteristics with them. Former phylogenetic analysis strongly and consistently supported it; they either form two distinct lineages with V. brassicaformis more closely related to apicomplexans (Janouškovec et al. 2010) or are sisters to them (Woo et al. 2015). According to the present analysis, one of the apicortin paralogs in both species, Vbra_15441 from V. brassicaformis and Cvel_6797 from C. velia, is sister to apicomplexan orthologs.

Two paralogs of both chromerids form a separate clade, which is sister to the clade of (apicomplexan apicortins + Vbra_15441 + Cvel_6797) in the Bayesian tree with high support. These clades together (the Alveolate apicortins) are separated from others with a high (0.99) support. However, in the ML tree, this separation does not hold. The latter chromerid paralogs are obviously the results of in-species duplications. However, the presence of three kinds of apicortins in C. velia and V. brassicaformis is not only the result of species-specific gene duplications but also the consequence of another gene duplication occurring in a common ancestor of these chromerids. In this case, we may consider their apicomplexan-like apicortin and nonapicomplexan-like apicortins as “outparalogs.” It signs paralogs in the given lineage that evolved by gene duplications happening before the speciation event (for this definition see Sonnhammer and Koonin 2002). The question is when it occurred. It might be happened in the direct chromerid ancestor as a lineage-specific event. Alternatively, and supported by the phylogenic analyses, it could be occurred in an early common ancestor of chromerids and Apicomplexa and one of these two ancient gene types was lost in the common ancestor of Apicomplexa but retained in chromerids. The progressive, lineage-specific gene losses during apicomplexan evolution have recently been demonstrated, in accordance with the change of life style from free-living to parasitic one (Woo et al. 2015). The Bayesian and the ML analyses suggest different answers what this early common ancestor was. According to the Bayesian tree, it can be the common ancestor of chromerids and Apicomplexa or that of the common ancestor of Myzozoa (see the next paragraph). The ML tree allows the common ancestor of Opisthokonta, Archaeplastida, and Chromalveolata, or even the common eukaryote ancestor. Finally, it should be added that horizontal transfer of the nonapicomplexan-like apicortin gene by the common ancestor of C. velia and V. brassicaformis also remains a possible scenario.

Recent analysis by Janouškovec et al. (2015) has shown that chromerids and colpodellids (predatory, nonphotosynthetic alveolates) form a single monophyletic sister group to apicomplexans with strong support. The group was named as “chrompodellids” by the authors. Within this group, however, neither chromerids nor colpodellids are monophyletic. No apicortin can be found among the available colpodellid sequences. However, no complete colpodellid genome is known so far; thus, at the current time, it is an open question whether they contain apicortin. Chrompodellids plus apicomplexans and dinoflagellates plus perkinsids form a monophyletic clade within Alveolata (Gile and Slamovits 2014; Janouškovec et al. 2015), which is collectively called myzozoans (Cavalier-Smith and Chao 2004), and is sister to Ciliata, another phylum of alveolates. Complete genomes of several ciliates are known; however, they do not possess apicortin. The draft genome of a dinoflagellate, Symbiodinium minutum, has been recently established (Shoguchi et al. 2013), but it does not seem to contain apicortin. However, the WGS of a Perkinsidae, Perkinsus marinus, contains a sequence homologous to apicortin (Orosz 2011), although the transcriptome analysis by Joseph et al. (2010), which identified several thousands of potential orthologs of known proteins, has not found apicortin among them. The presence of apicortin in Apicomplexa, in Chromerida, and maybe in Perkinsidae (at least its remnants in the genome) suggests that the common ancestor of Myzozoa also possessed apicortin. This wider phyletic occurrence makes less enigmatic the impressive presence of this protein in apicomplexans. However, outside of Myzozoa, apicortin occurs only episodically.

Conclusions

The recent data strengthen our view that the presence of apicortins is predominantly characteristic of the phylum of Apicomplexa. All the sequenced apicomplexan species, without exception, contain an apicortin. This paper identifies novel apicortin orthologs and corrects in several cases the erroneous sequences of hypothetical apicortin proteins of Cryptosporidium, Eimeria and Theileria genera published in databases. The sequences of apicortins of the Plasmodium genus, except P. gallinaceum, member of the Haemamoeba subgenus, differ significantly from the other apicomplexan apicortins. The feature of this newly identified ortholog suggests that originally Plasmodium apicortins were more similar to the other ones than today and only orthologs of Plasmodiums hosted by mammals altered significantly. Apicomplexan apicortins contain a long, unstructured N-terminus which is different in the various apicomplexan families and cannot be found in the few nonapicomplexan orthologs. It is true even for their closest Alveolate relatives, the recently described Chromerida. These species, C. velia and V. brassicaformis, are the only ones which contain more than one (actually, three) paralogs. Their apicomplexan-type and nonapicomplexan-type apicortins might be considered as “outparalogs.” Some new Opisthokont orthologs have also been found. The fungal one, R. allomycis, found at protein level, is similar to the known Opisthokont (T. adhaerens, S. punctatus) ones. The algal N. mirabilis apicortin was found as TSA. An apicortin from an insect, A. curtula, and one from an echinodermata, A. japonicas, found also as TSAs, are more surprising findings since in Eumetazoa no apicortin has been found until know. However, we should be cautious until whole genome sequences will be available; they may be either contaminations or, less probably, the result of horizontal gene transfer. However, there are other cases when the contamination can be proved.

References

Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 25:3389–3402

Aurrecoechea C, Brestelli J, Brunk BP, Dommer J, Fischer S, Gajria B, Gao X, Gingle A, Grant G, Harb OS, Heiges M, Innamorato F, Iodice J, Kissinger JC, Kraemer E, Li W, Miller JA, Nayak V, Pennington C, Pinney DF, Roos DS, Ross C, Stoeckert CJ Jr, Treatman C, Wang H (2009) PlasmoDB: a functional genomic database for malaria parasites. Nucleic Acids Res 37:D539–D543

Aurrecoechea C, Heiges M, Wang H, Wang Z, Fischer S, Rhodes P, Miller J, Kraemer E, Stoeckert CJ Jr, Roos DS, Kissinger JC (2007) ApiDB: integrated resources for the apicomplexan bioinformatics resource center. Nucleic Acids Res 35:D427–D430

Barta JR, Thompson RC (2006) What is Cryptosporidium? reappraising its biology and phylogenetic affinities. Trends Parasitol 22:463–468

Cavalier-Smith T, Chao EE (2004) Protalveolate phylogeny and systematics and the origins of Sporozoa and dinoflagellates (phylum Myzozoa nom. nov.). Eur J Protistol 40:185–212

Chen JW, Romero P, Uversky VN, Dunker AK (2006) Conservation of intrinsic disorder in protein domains and families: II. functions of conserved disorder. J Proteom Res 5:888–898

Dosztányi Z, Csizmok V, Tompa P, Simon I (2005) IUPred: web server for the prediction of intrinsically unstructured regions of proteins based on estimated energy content. Bioinformatics 21:3433–3434

Felsenstein J (2008) PHYLIP (Phylogeny inference package) version 3.696, Department of Genome Sciences and Department of Biology University of Washington Seattle WA. http://evolution.genetics.washington.edu/phylip.html

Feng ZP, Zhang X, Han P, Arora N, Anders RF, Norton RS (2006) Abundance of intrinsically unstructured proteins in P, falciparum and other apicomplexan parasite proteomes. Mol Biochem Parasitol 150:256–267

Finn RD, Tate J, Mistry J, Coggill PC, Sammut SJ, Hotz HR, Ceric G, Forslund K, Eddy SR, Sonnhammer EL, Bateman A (2008) The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res 36:D281–D288

Gile GH, Slamovits CH (2014) Transcriptomic analysis reveals evidence for a cryptic plastid in the colpodellid Voromonas pontica a close relative of chromerids and apicomplexan parasites. PLoS One 9:e96258. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096258

Gajria B, Bahl A, Brestelli J, Dommer J, Fischer S, Gao X, Heiges M, Iodice J, Kissinger JC, Mackey AJ, Pinney DF, Roos DS, Stoeckert CJ Jr, Wang H, Brunk B (2008) ToxoDB: an integrated Toxoplasma gondii database resource. Nucleic Acids Res 36:D553–D556

Heekin AM, Guerrero FD, Bendele KG, Salvidar L, Scoles GA, Gondro C, Nene V, Djikeng A, Brayton KA (2012) Analysis of Babesia bovis infection-induced gene expression changes in larvae from the cattle tick Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus. Parasit Vectors 5:162. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-5-162

Heiges M, Wang H, Robinson E, Aurrecoechea C, Gao X, Kaluskar N, Rhodes P, Wang S, He CZ, Su Y, Miller J, Kraemer E, Kissinger JC (2006) CryptoDB: a Cryptosporidium bioinformatics resource update. Nucleic Acids Res 34:D419–D422

Hertz-Fowler C, Peacock CS, Wood V, Aslett M, Kerhornou A, Mooney P, Tivey A, Berriman M, Hall N, Rutherford K, Parkhill J, Ivens AC, Rajandream MA, Barrell B (2004) GeneDB: a resource for prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms. Nucleic Acids Res 32:D339–D343

Hlavanda E, Kovács J, Oláh J, Orosz F, Medzihradszky KF, Ovádi J (2002) Brainspecific p25 protein binds to tubulin and microtubules and induces aberrant microtubule assemblies at substoichiometric concentrations. Biochemistry 417:8657–8664

Hunter S, Apweiler R, Attwood TK, Bairoch A, Bateman A, Binns D, Bork P, Das U, Daugherty L, Duquenne L, Finn RD, Gough J, Haft D, Hulo N, Kahn D, Kelly E, Laugraud A, Letunic I, Lonsdale D, Lopez R, Madera M, Maslen J, McAnulla C, McDowall J, Mistry J, Mitchell A, Mulder N, Natale D, Orengo C, Quinn AF, Selengut JD, Sigrist CJ, Thimma M, Thomas PD, Valentin F, Wilson D, Wu CH, Yeats C (2009) InterPro: the integrative protein signature database. Nucleic Acids Res 37:D211–D215

Janouškovec J, Horák A, Oborník M, Lukeš J, Keeling PJ (2010) A common red algal origin of the apicomplexan dinoflagellate and heterokont plastids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:10949–10954. doi:10.1073/pnas.1003335107

Janouškovec J, Tikhonenkov DV, Burki F, Howe AT, Kolísko M, Mylnikov AP, Keeling PJ (2015) Factors mediating plastid dependency and the origins of parasitism in apicomplexans and their close relatives. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112:10200–102007. doi:10.1073/pnas.1423790112

Jones DT, Taylor WR, Thornton JM (1992) The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput Appl Biosci 8:275–282

Joseph SJ, Fernández-Robledo JA, Gardner MJ, El-Sayed NM, Kuo CH, Schott EJ, Wang H, Kissinger JC, Vasta GR (2010) The Alveolate Perkinsus marinus: biological insights from EST gene discovery. BMC Genomics 11:228. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-11-228

Kim MH, Cierpicki T, Derewenda U, Krowarsch D, Feng Y, Devedjiev Y, Dauter Z, Walsh CA, Otlewski J, Bushweller JH, Derewenda ZS (2003) The DCX domain tandems of doublecortin and doublecortin-like kinase. Nat Struct Biol 10:324–333

Lara E, Moreira D, López-García P (2010) The environmental clade LKM11 and Rozella form the deepest branching clade of fungi. Protist 161:116–121

Leander BS (2008) Marine gregarines: evolutionary prelude to the apicomplexan radiation? Trends Parasitol 24:60–67

Liu YJ, Hodson MC, Hall BD (2006) Loss of the flagellum happened only once in the fungal lineage: phylogenetic structure of kingdom Fungi inferred from RNA polymerase II subunit genes. BMC Evol Biol 6:74. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-6-74

Marchler-Bauer A, Anderson JB, Derbyshire MK, DeWeese-Scott C, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, Hao L, He S, Hurwitz DI, Jackson JD, Ke Z, Krylov D, Lanczycki CJ, Liebert CA, Liu C, Lu F, Lu S, Marchler GH, Mullokandov M, Song JS, Thanki N, Yamashita RA, Yin JJ, Zhang D, Bryant SH (2007) CDD: a conserved domain database for interactive domain family analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 35:D237–D240

Moore RB, Oborník M, Janouškovec J, Chrudimský T, Vancová M, Green DH, Wright SW, Davies NW, Bolch CJ, Heimann K, Šlapeta J, Hoegh-Guldberg O, Logsdon JM, Carter DA (2008) A photosynthetic alveolate closely related to apicomplexan parasites. Nature 451:959–963

Morrison DA (2009) Evolution of the Apicomplexa: where are we now? Trends Parasitol 25:375–382

Oborník M, Modrý D, Lukeš M, Cernotíková-Stříbrná E, Cihlář J, Tesařová M, Kotabová E, Vancová M, Prášil O, Lukeš J (2012) Morphology ultrastructure and life cycle of Vitrella brassicaformis n. sp., n. gen., a novel chromerid from the Great Barrier Reef. Protist 163:306–323

Obradovic Z, Peng K, Vucetic S, Radivojac P, Dunker AK (2005) Exploiting heterogeneous sequence properties improves prediction of protein disorder. Proteins 61(S7):176–182

Orosz F (2009) Apicortin, a unique protein, with a putative cytoskeletal role, shared only by apicomplexan parasites and the placozoan Trichoplax adhaerens. Infect Genet Evol 9:1275–1286

Orosz F (2011) Apicomplexan apicortins possess a long disordered N-terminal extension. Infect Genet Evol 11:1037–1044

Orosz F (2012) A new protein superfamily: TPPP-like proteins. PLoS One 7:e49276. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049276

Orosz F (2015) Two recently sequenced vertebrate genomes are contaminated with apicomplexan species of the Sarcocystidae family. Int J Parasitol 45:871–878. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2015.07.002

Orosz F, Ovádi J (2008) TPPP orthologs are ciliary proteins. FEBS Lett 582:3757–3764

Ovádi J, Orosz F (2009) An unstructured protein with destructive potential: TPPP/p25 in neurodegeneration. BioEssays 31:676–686. doi:10.1002/bies.200900008

Reid AJ, Blake D, Billington K, Browne H, Dunn M, Hung S, Kawahara F, Miranda-Saavedra D, Mourier T, Nagra H, Otto TD, Rawlings N, Sanchez A, Sanders M, Subramaniam C, Tay Y, Dear P, Doerig C (2014) Genomic analysis of the causative agents of coccidiosis in domestic chickens. Genome Res 24:1676–1685. doi:10.1101/gr.168955.113

Ringrose JH, van den Toorn HWP, Eitel M, Post H, Neerincx P, Schierwater B, Altelaar AFM, Heck AJR (2013) Deep proteome profiling of Trichoplax adhaerens reveals remarkable features at the origin of metazoan multicellularity. Nat Commun 4:1408. doi:10.1038/ncomms2424

Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP (2003) MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixture models. Bioinformatics 19:1572–1574

Sapir T, Horesh D, Caspi M, Atlas R, Burgess HA, Wolf SG, Francis F, Chelly J, Elbaum M, Pietrokovski S, Reiner O (2000) Doublecortin mutations cluster in evolutionarily conserved functional domains. Hum Mol Genet 9:703–712

Shoguchi E, Shinzato C, Kawashima T, Gyoja F, Mungpakdee S, Koyanagi R, Takeuchi T, Hisata K, Tanaka M, Fujiwara M, Hamada M, Seidi A, Fujie M, Usami T, Goto H, Yamasaki S, Arakaki N, Suzuki Y, Sugano S, Toyoda A, Kuroki Y, Fujiyama A, Medina M, Coffroth MA, Bhattacharya D, Satoh N (2013) Draft assembly of the Symbiodinium minutum nuclear genome reveals dinoflagellate gene structure. Curr Biol 23:1399–1408. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.05.062

Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Söding J, Thompson JD, Higgins DG (2011) Fast scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol 7:539. doi:10.1038/msb.2011.75

Sonnhammer EL, Koonin EV (2002) Orthology, paralogy and proposed classification for paralog subtypes. Trends Genet 18:619–620

Templeton TJ, Enomoto S, Chen WJ, Huang CG, Lancto CA, Abrahamsen MS, Zhu G (2010) A genome-sequence survey for Ascogregarina taiwanensis supports evolutionary affiliation but metabolic diversity between a Gregarine and Cryptosporidium. Mol Biol Evol 27:235–248

Tirián L, Hlavanda E, Oláh J, Horváth I, Orosz F, Szabó B, Kovács J, Szabad J, Ovádi J (2003) TPPP/p25 promotes tubulin assemblies and blocks mitotic spindle formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:13976–13981

Vincze O, Tőkési N, Oláh J, Hlavanda E, Zotter Á, Horváth I, Lehotzky A, Tirián L, Medzihradszky KF, Kovács J, Orosz F, Ovádi J (2006) TPPP proteins members of a new family with distinct structures and functions. Biochemistry 45:13818–13826

Wakeman KC, Leander BS (2012) Molecular phylogeny of Pacific Archigregarines (Apicomplexa) including descriptions of Veloxidium leptosynaptae n. gen., n. sp., from the sea cucumber Leptosynapta clarki (Echinodermata) and two new species of Selenidium. J Eukaryot Microbiol 59:232–245

Whelan S, Goldman N (2001) A general empirical model of protein evolution derived from multiple protein families using a maximum-likelihood approach. Mol Biol Evol 18:691–699

Woo YH, Ansari H, Otto TD, Klinger CM, Kolisko M, Michálek J, Saxena A, Shanmugam D, Tayyrov A, Veluchamy A, Ali S, Bernal A, del Campo J, Cihlář J, Flegontov P, Gornik SG, Hajdušková E, Horák A, Janouškovec J, Katris NJ, Mast FD, Miranda-Saavedra D, Mourier T, Naeem R, Nair M, Panigrahi AK, Rawlings ND, Padron-Regalado E, Ramaprasad A, Samad N, Tomčala A, Wilkes J, Neafsey DE, Doerig C, Bowler C, Keeling PJ, Roos DS, Dacks JB, Templeton TJ, Waller RF, Lukeš J, Oborník M, Pain A (2015) Chromerid genomes reveal the evolutionary path from photosynthetic algae to obligate intracellular parasites. Elife 4:e06974. doi:10.7554/eLife.06974

Zhu Z, Dumas JJ, Lietzke SE, Lambright DG (2001) A helical turn motif in Mss4 is a critical determinant of Rab binding and nucleotide release. Biochemistry 40:3027–3036

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Dr. Judit Oláh for the careful reading of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

239_2016_9749_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

2. Newly identified apicortins and similar sequences. Exons are labeled by alternating italic and bold letters. Italic and bold labeling at the same time indicates that the amino acid is encoded by nucleotides of two exons. Asterisks indicate that the sequences were corrected by the author (cf. Online Resource 3.). Underlined amino acids in Plasmodium berghei and in Plasmodium falciparum indicate that these apicortins have been known before but their sequences were corrected in the databases by the insertion of the underlined sequences. TSA, Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly; WGS, Whole Genome Shotgun; Orf—Open reading frame. Supplementary material 2 (PDF 107 kb)

239_2016_9749_MOESM4_ESM.pdf

4. Corrected apicortin sequences. Exons are labeled by alternating italic and bold letters. The sequences from the databases are in parenthesis. Wrong sequences are lined through, corrected ones are underlined. Both are labeled by small letters and grey color as well. Supplementary material 4 (PDF 15 kb)

239_2016_9749_MOESM5_ESM.pdf

5. Is Aleochara curtula GATW02017439 TSA sequence a contamination from a gregarine? Supplementary material 5 (PDF 200 kb)

239_2016_9749_MOESM6_ESM.pdf

6. Rhipicephalus microplus TC356 mRNA sequence is a contamination from Babesia bovis. Supplementary material 6 (PDF 173 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Orosz, F. Wider than Thought Phylogenetic Occurrence of Apicortin, A Characteristic Protein of Apicomplexan Parasites. J Mol Evol 82, 303–314 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00239-016-9749-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00239-016-9749-5