Abstract

Introduction

Acute akathisia is a neuropsychiatric syndrome with a negative effect on illness outcome. Its incidence in patients treated with antipsychotics has shown to be highly variable across studies.

Objectives

Our goals were to investigate prevalence, risk factors for the development of acute akathisia, and differences in incidence between antipsychotics in a sample of 493 first episode non-affective psychosis patients.

Methods

This is a pooled analysis of three prospective, randomized, flexible-dose, and open-label clinical trials. Patients were randomized assigned to different arms of treatment (haloperidol, quetiapine, olanzapine, ziprasidone, risperidone, or aripiprazole). Akathisia was determined using the Barnes Akathisia Scale at 6 weeks after antipsychotic initialization. Univariate analyses were performed to identify demographic, biochemical, substance use, clinical, and treatment-related predictors of acute akathisia. Considering these results, a predictive model based of a subsample of 132 patients was constructed with akathisia as the dependent variable.

Results

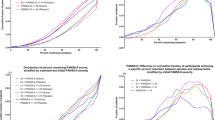

The overall incidence of akathisia was 19.5%. No differences in demographic, biochemical, substance use, and clinical variables were found. Significant incidence differences between antipsychotics were observed (Χ 2 = 68.21, p = 0.000): haloperidol (57%), risperidone (20%), aripiprazole (18.2%), ziprasidone (17.2%), olanzapine (3.6%), and quetiapine (3.5%). The predictive model showed that the type of antipsychotic (OR = 21.3, p = 0.000), need for hospitalization (OR = 2.6, p = 0.05), and BPRS total score at baseline (OR = 1.05, p = 0.03) may help to predict akathisia emergence.

Conclusions

Among second generation antipsychotics, only olanzapine and quetiapine should be considered as akathisia-sparing drugs. The type of antipsychotic, having been hospitalized, and a more severe symptomatology at intake seem to predict the development of acute akathisia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Acute akathisia is a neuropsychiatric syndrome consisting of a combination of subjective and objective psychomotor restlessness (Sachdev 1995) that usually emerges a few days or weeks after starting or raising the dose of antipsychotic medications or after reducing the dose of drugs used to treat extrapyramidal symptoms (Miller et al. 1997; Espi-Forcen et al. 2016). In clinical practice, it is underdiagnosed because of the difficulty in identifying the subjective symptoms (Hirose 2003). Several lines of evidence suggest that akathisia may be associated to a low or high activity of dopaminergic projections from the midbrain to the ventral (nucleus accumbens) or dorsal striatum (Loonen and Stahl 2011, Stahl 2013), producing an imbalance between dopamine and acetylcholine in the striatum (Stahl 2013).

The prevalence of akathisia in patients treated with antipsychotics is highly variable across different studies. It has been described that the prevalence of akathisia is approximately 25% in individuals on first generation antipsychotics (FGA) (Miller et al. 1997; Berna et al. 2015), whereas a recent study carried out in routine clinical practice reported a lower prevalence (18.5%) in patients taking second generation antipsychotics (SGA) (Berna et al. 2015).

Acute akathisia may have a negative impact on clinical outcome. It is associated to higher levels of anxiety (Hansen 2001; Kim and Byun 2010), discomfort, and dysphoria, and may increase the risk of suicide (Cematbasoglu et al. 2001; Hansen 2001; Seemüller et al. 2012) and worsen the course of psychosis (Mathews et al. 2005; Caseiro et al. 2012), partly because it is associated with dropping out of treatment (Berardi et al. 2000). Hence, the ability to predict its emergence could be of important clinical interest especially in first episode psychosis (FEP), as akathisia usually emerges during the first weeks following the onset of treatment. The influences of clinical or demographic factors predisposing patients to the development of acute akathisia remain unsolved. Whereas past studies indicate that neither age nor gender significantly influenced the prevalence of akathisia (Miller et al. 1997; Chong et al. 2002), there seems to be evidence of an association between this syndrome and a prior presence of substance abuse, especially cocaine (Maat et al. 2008; Potvin et al. 2009). Smoking seems to not reduce the symptoms of akathisia (De León et al. 2006). The relationship between akathisia and a measurable deficit in body iron stores has been studied with unequal findings (Barnes et al. 1992; Soni et al. 1993; Hofmann et al. 2000; Kuloglu et al. 2003; Cotter and O’Keeffe 2007). The available data regarding the association of akathisia with other risk factors, such as cognitive dysfunction (Kim and Byun 2007), duration of illness (Hansen et al. 2013), or acculturation (Sundram et al. 2008), are inconclusive. Respecting the risk of developing akathisia with specific antipsychotics, two systematic reviews suggest that SGAs are more benign that FGAs (Haddad et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2013), whereas differences between individual SGAs appear to be less clear, in part because of the paucity of head-to-head comparison studies (Miller et al. 2008; Peluso et al. 2012; Haddad et al. 2012; Leucht et al. 2013).

Most studies that have studied risk factors for developing akathisia have been carried out with chronic or institutionalized patients, often cross-sectionally and with no relation to acute psychosis treatment. A few studies to date have compared the risk of acute akathisia among the commonly used antipsychotics in drug-naïve FEP patients (Green et al. 2006; Möller et al. 2008; Pappa and Dazzan 2009; Haddad et al. 2012; Amr et al. 2013; Lee et al. 2016). There seems to be a narrow threshold between the dose needed to reduce positive symptoms and that for producing akathisia (Robinson et al. 2005). Both high doses and rapidly increasing doses of antipsychotic drugs have been related to the development of acute akathisia (Mathews et al. 2005; Basu and Brar 2006; Poyurovsky 2010).

The aim of this study is to prospectively investigate the incidence of acute akathisia at 6 weeks in a large sample of drug-naïve FEP patients. Analyses will include both the incidence differences between antipsychotics as well as the identification of risk factors involved in the development of akathisia.

Methods

Study setting

Data for the present research were obtained from a large epidemiological cohort of patients who have been treated in a longitudinal intervention program of FEP called PAFIP (Programa de Atención a Fases Iniciales de Psicosis) conducted at the University Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla in Cantabria, Spain. The main procedures that are carried out in this program have been described previously (Pelayo-Terán et al. 2008). The program was approved by the local institutional review board and informed consent was attained from patients and their families prior to inclusion.

Subjects

From February 2001 to August 2015, all patients with FEP were included in PAFIP according to the following criteria: (1) age between 15 and 60, (2) residency in the catchment area, (3) experiencing their first episode of psychosis, (4) no prior treatment with antipsychotic medication or, if previously treated, a total time of adequate antipsychotic treatment shorter than 6 weeks, and (5) DSM-IV criteria for brief psychotic disorder, schizophreniform disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or psychotic disorder not otherwise specified. Patients were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (1) DSM-IV criteria for drug dependence, (2) DSM-IV criteria for mental retardation, and (3) history of neurological disorder or brain injury. The diagnoses were confirmed by an experienced psychiatrist, applying the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I) 6 months following the baseline visit.

Study design

This is a pooled analysis of three different clinical trials encompassing all first episode patients who were admitted to PAFIP from 2001 to 2015 (NCT02305823, EudraCT 2013-005399-16) (Crespo-Facorro et al. 2006, 2014). These three clinical trials were prospective, randomized, flexible-dose, and open-label. Patients were randomly assigned to different arms of treatment (haloperidol, quetiapine, olanzapine, ziprasidone, risperidone, or aripiprazole) according to the research protocol of each clinical trial. Out of 541 patients who were initially included in the pooled analysis, 48 subjects were excluded from the final analysis since they did not have any post-baseline akathisia measure (Barnes Akathisia Scale). Therefore, the final sample consisted of 493 subjects. At intake, all but 36 patients were antipsychotic naïve. Those patients who were taking antipsychotics at the moment of inclusion into the program underwent a 5-day washout period before starting treatment. No patients were diagnosed with akathisia prior to randomization. Mean antipsychotic dose expressed as chlorpromazine equivalent (CPZeq; mg/day) (APA 2013; Wood 2003) was as follows: haloperidol 3–9 mg/day (150–450 mg/day of chlorpromazine), risperidone 3–6 mg/day (150–300 mg/day of chlorpromazine), olanzapine 5–20 mg/day (100–400 mg/day of chlorpromazine), quetiapine 100–600 mg/day (133.33–800 mg/day of chlorpromazine), ziprasidone 40–160 mg/day (66.67–266.67 mg/day of chlorpromazine), and aripiprazole 5–30 mg/day (66,67–400 mg/day of chlorpromazine). The study’s protocol allowed for the use of anticholinergic agents, benzodiazepines and antidepressants for clinical reasons. Anticholinergic medication was never used prophylactically.

Assessments

For the purpose of the present investigation, only the first 6 weeks following the onset of treatment was considered, since this is the critical period for the onset of acute akathisia. The scale used to evaluate the presence of akathisia was the Barnes Akathisia Scale (BAS) (Barnes 1989). The BAS was designed so that those using it would be directed to look for the characteristic motor phenomena as well as systematically probe the subjective aspects of akathisia, including the amount of discomfort and distress that might be reasonably attributed to the condition. With the information gained, an overall measure of severity could be made using the global item (0: absent, 1: questionable, 2: mild akathisia, 3: moderate akathisia, 4: marked akathisia, and 5: severe akathisia). The use of the global item for diagnosis of akathisia has proven to have high inter-rater validity as well as adequate reliability when compared to neurophysiological complementary tests (Barnes 1989; Janno et al. 2005). The diagnoses of akathisia are determined by a score ≥2 on the global item of the BAS (Barnes 1989). In our study, the presence of akathisia was evaluated at baseline and at 6 weeks following the onset of antipsychotic treatment. At baseline, all patients had a BAS global score <2; namely, they did not have neither objective nor subjective symptoms of akathisia.

With regard to those patients who were taking biperiden during the follow-up and with a BAS global score of <2 at 6-week assessment, medical record was reviewed to verify if they have met DSM-IV criteria for the diagnosis of neuroleptic-induced akathisia at any point during the follow-up period. If they met these criteria, they were also considered as akathisic patients.

Sociodemographic and clinical information were obtained from patients and their relatives at baseline: age, duration of untreated illness (DUI), and duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) were coded as continuous variables, whereas gender, level of studies, need for hospitalization, and use of substances of abuse were coded as binary variables. At entry, general psychopathology was assessed with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (Flemenbaum and Zimmermann 1973), whereas positive and negative dimensions of psychosis were measured with the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) (Andreasen 1984), and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (Andreasen 1983). Fasting venous blood samples were collected at baseline, and were analyzed for glycemia, serum iron and copper, vitamin B12, and folic acid by automated methods. Antipsychotics and other concomitant treatments were recorded during the following 6 weeks.

Statistical analysis

All data were tested for normality (using Shapiro-Wilk test and normal probability plot) and equality of variances (using Levene test). Univariate analyses were performed to identify plausible demographic, clinical, and treatment-related predictors of acute akathisia. Sociodemographic and clinical variables, as well as the differences between antipsychotics were analyzed by group (akathisic and non-akathisic) using the chi-square test. Continuous variables were also analyzed by group using the t test, W-Wilcoxon, or ANOVA as necessary. A post hoc pairwise comparison in akathisia rates was established between groups of antipsychotic drugs, performing repeated chi-square tests with a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Additionally, a logistic regression model was carried out with akathisia as the dependent variable. For this part of the analysis, our sample population was separated into two groups based on which antipsychotic they received. The variables introduced as predictors were those with a significance level equal or lower than 20% in the univariate analysis, those associated with the severity of the illness at onset, and also those suggestive of having a role in the development of acute akathisia. Backward stepwise selection was used to create the final model. This procedure performs a sequential exclusion of variables based on p values ≥0.10, which is complementary with the inclusion of those ≤0.05.

STATA 14.2 was used for statistical analyses. Statistical tests were two-tailed with a 95% confidence interval.

Results

Sample characteristics

According to the Shapiro-Wilk test and normal probability plot, all variables followed a normal distribution except for the DUP. Parametric tests were thus used for all variables except for DUP, where a non-parametric test was used (W-Wilcoxon). The Levene test showed equality of variance for all variables.

Incidence of acute akathisia

Acute akathisia was diagnosed in 96 patients (19.5%) at 6 weeks after randomization. Out of 96 patients, 66 (68.75%) were diagnosed using the BAS at 6 weeks and 30 (31.25%) were patients who were taking biperiden during the follow-up period, had a BAS global score of <2 at 6-week assessment, and were diagnosed with acute akathisia because they had objective or subjective symptoms of akathisia recorded in their clinical history.

Differences in sociodemographic and clinical variables

As shown in Table 1, there were no statistically significant differences between akathisic and non-akathisic patients in terms of demographic and clinical variables (all ps > 0.1) nor between the two groups in additional laboratory parameters: serum iron, p = 0.10; glycemia, p = 0.670; serum copper, p = 0.700; vitamin B12, p = 0.458; and folic acid, p = 0.843.

Comparison between antipsychotic groups

Out of 493 subjects of the entire sample, 143 were initially randomized to aripiprazole, 125 to risperidone, 58 to quetiapine, 58 to ziprasidone, 55 to olanzapine, and 54 to haloperidol. The incidence of akathisia was significantly associated with the antipsychotic drug at baseline (Χ 2 = 68.21; p = 0.000), as can be seen in Table 2. Prescription rates at baseline of benzodiazepines (Χ 2 = 0.09; p = 0.765), antidepressants (Χ 2 = 0.27; p = 0.606), and antipsychotic doses (t = 0.11; p = 0.912) were comparable between the two groups. However, there was a statistically significant difference of CPZeq mean doses when antipsychotics were compared head to head. Patients on olanzapine and quetiapine had the highest CPZeq mean doses (p = 0.000).

As evident in Table 2, haloperidol-randomized patients developed more akathisia (57%) and required anticholinergic agents more often (76%) than did patients administered the other antipsychotics. Repeated chi-square tests, after adjustment by Bonferroni correction, revealed that akathisia was significantly higher in the haloperidol group than in the remaining groups: haloperidol vs risperidone (Χ 2 = 24.55, p = 0.000), haloperidol vs aripiprazole (Χ 2 = 29.33, p = 0.000), haloperidol vs ziprasidone (Χ 2 = 19.44, p = 0.000), haloperidol vs olanzapine (Χ 2 = 37.32, p = 0.000), and haloperidol vs quetiapine (Χ 2 = 39.18, p = 0.000). Meanwhile, the rate of akathisia among patients administered risperidone (20%) and aripiprazole (18.2%) was greater than olanzapine (3.6%) and quetiapine (3.5%): risperidone vs olanzapine (Χ 2 = 8.00; p = 0.023), risperidone vs quetiapine (Χ 2 = 8.63, p = 0.017), aripiprazole vs olanzapine (Χ 2 = 6.92, p = 0.043), and aripiprazole vs quetiapine (Χ 2 = 7.47, p = 0.031). In respect to the incidence of akathisia with ziprasidone (17%), no significant differences between this antipsychotic and other SGAs were not found: ziprasidone vs olanzapine (Χ 2 = 5.51, p = 0.095), ziprasidone vs quetiapine (Χ 2 = 5.95, p = 0.073), ziprasidone vs risperidone (Χ 2 = 0.19, p = 1.000), and ziprasidone vs aripiprazole (Χ 2 = 0.02, p = 1.000). Finally, the rate of akathisia was similar between both aripiprazole and risperidone (Χ 2 = 0.14, p = 1.000) and olanzapine and quetiapine (Χ 2 = 0.003, p = 1.000).

Predictive model

The final aim of the current study was to identify possible risk factors in the development of akathisia. As it was mentioned before, for this part of the analysis our sample population was separated into two groups based on which antipsychotic they received. The “pro-akathisic” group consisted of those patients that had received one of the antipsychotics with higher incidence of akathisia: haloperidol, risperidone, or aripiprazole. The “non-akathisic” group consisted of those patients who had received one of the low incidence antipsychotics: ziprasidone, olanzapine, or quetiapine. From the original sample population, 132 patients were selected that had available data across the following variables: type of antipsychotic at baseline (pro/non-akathisic), age at onset of psychosis, serum iron level, total score on BPRS at baseline, total score on SAPS at baseline, smoker status (yes/no), and need for hospitalization (yes/no).

After adjusting the model in accordance with backward stepwise selection, the results reveal that the type of antipsychotic drug (OR = 21.3; p = 0.000), need for hospitalization (OR = 2.6; p = 0.05), and total-score on BPRS at baseline (OR = 1.05; p = 0.03) significantly accounted for incidence of akathisia. The model was statistically significant (LR Χ 2 = 36.72; p = 0.000) and accounted for 22.7% of the variance (pseudo R 2 = 0.2268). The model correctly predicted 78% of patient outcomes, with high specificity (87.0%) but lower sensitivity (57.5%). The positive predictive value of the model was 65.7%, whereas the negative predictive value was higher (82.5%). In addition, the ROC (receiver operating characteristic) curve showed an area under the curve (AUC) of 81%.

Discussion

The overall incidence of akathisia at 6 weeks was 19.5%. A higher incidence of akathisia was identified in individuals on the FGA haloperidol. These findings are consistent with those reported in clinical trials also conducted on FEP samples (Green et al. 2006; Möller et al. 2008; Haddad et al. 2012; Amr et al. 2013; Lee et al. 2016). Some authors have suggested that the differences between SGA and FGA on akathisia rates may result from a use of markedly high doses of haloperidol in regular clinical practice (Kumar and Sachdev 2009). Interestingly, in our study the initial and 6-week mean dose of haloperidol was somewhat low when compared with SGA doses. In fact, as shown in Table 2, the highest CPZeq mean doses at baseline and at 6 weeks were found in those patients treated with olanzapine and quetiapine, respectively, which are the two antipsychotics with the lowest ratios of akathisia (p = 0.000). However, it is important to take into account that the validity of CPZeq across first and second generation antipsychotics has not been convincingly demonstrated and that these equivalences are not related to dopamine D2 receptor antagonism of each individual antipsychotic (Atkins et al. 1997; Danivas and Venkatasubramanian 2013; Stahl 2013). Several studies (Mathews et al. 2005; Basu and Brar 2006; Opjordsmoen et al. 2009; Poyurovsky 2010) found that if antipsychotics were analyzed separately, akathisia emerged with more probability in those patients with higher doses or rapidly increasing doses of whatever type of antipsychotic. Other authors have argued that the ratio of akathisia depends on the type of antipsychotic and the combination of two or more antipsychotics (Lieberman et al. 2003; Berna et al. 2015). Large multisite clinical trials did not reveal significant differences on akathisia rates between different SGAs, either in chronic (Miller et al. 2008) or in FEP populations (Gafoor et al. 2010). The relative scarcity of head-to-head studies results in quite inadequate evidence on the issue. We have found a fairly clear gradation between different SGAs, both in the incidence of akathisia and in the need for adjuvant anticholinergic medication. Whereas risperidone and aripiprazole were associated with an increased risk of acute akathisia, this risk seems to be very low for olanzapine and quetiapine (San et al. 2012; Leucht et al. 2013). Ziprasidone appears to take an intermediate place between them. The rate of akathisia in the current sample was very similar for risperidone and aripiprazole. This stands in contrast with recent findings where aripiprazole was associated with a higher incidence than risperidone (Robinson et al. 2015). It has also been suggested that antipsychotics that do not notably cause sedation (risperidone or aripiprazole) do not mask the effects of akathisia as those antipsychotics (olanzapine and quetiapine) that are known to cause sedation (Thomas et al. 2015). Finally, the use of benzodiazepines or antidepressants at baseline seems not to influence the incidence of akathisia. Antidepressant prescription was nonetheless very limited, restraining the implications of this conclusion.

No differences in either baseline demographic or clinical features were observed between akathisic and non-akathisic patients. In contrast to other motor symptoms, which have been described in drug-naïve patients and have therefore been linked to the pathophysiology of schizophrenia (Pappa and Dazzan 2009; Peralta and Cuesta 2011), akathisia might be a treatment-derived syndrome. We failed to confirm previous findings based on chronic patients that linked an increased prevalence of akathisia with the use of substances of abuse, namely, cocaine (Potvin et al. 2006), alcohol (Hansen et al. 2013), or cannabis (Zhornitsky et al. 2010). Finally, our data do not support the relationship between tobacco smoking and lower rates of akathisia (De León et al. 2006).

In our study, serum iron levels were higher in the akathisic group, although this difference was not statistically significant. The hypothesis that low serum iron levels are associated with the development of akathisia (O’Loughlin et al. 1991; Kuloglu et al. 2003) was originated from a possible pathophysiological analogy between akathisia and restless leg syndrome. However, this hypothesis was not demonstrated in other studies (Soni et al. 1993; Hofmann et al. 2000). As far as we know, this is the first study where serum iron levels were somewhat higher in the akathisic group.

With regard to the predictive model, there are also some important considerations to highlight. The introduction of serum iron level as a possible predictor variable resulted in a decrease in the original sample from 493 to 132 patients. The rationale behind entering serum iron level in the predictive model was that serum iron levels were higher in our akathisic group than expected according to former investigations and also because the significance was under 20% in the univariate analysis (p = 0.10). This smaller sample led to a classification accuracy of 78%. As the results showed, type of antipsychotic, need for hospitalization, and total-score on BPRS were indicative of incidence of akathisia. The effect of the type of antipsychotic in developing akathisia has already been discussed above. Next, we consider the other two predictor variables: need for hospitalization and total score on BPRS. These two variables might both be associated with the need to use higher doses and rapidly increasing doses of antipsychotics at onset to reduce the severity of symptoms, which in turn can increase the risk of developing akathisia (Basu and Brar 2006; Opjordsmoen et al. 2009; Poyurovsky 2010). Taken together, they appear to predict the emergence of acute akathisia in FEP.

This study has several limitations that should be considered. First, despite a high homogeneity between three study protocols, the pooling of results into an open single case-control study reduces the statistical power of the findings. Second, neither patients nor clinical assessors were blind to treatment conditions, which could have had an impact on the reported akathisia rates. Nevertheless, as a non-industry-funded study, the risk for systematic error on measured outcomes is limited. Third, although the study sample was considerably large (n = 493) at outset, available information for some variables (e.g., serum iron level) limited the sample to far fewer patients (n = 132). Fourth, the clinical impact of acute akathisia in terms of dropping out of treatment, worsening of psychosis, or increasing the risk of suicide was not measured in this short-term study. These questions will be analyzed in future research of long-term patient outcomes.

In summary, almost 20% of patients will develop akathisia during the first weeks after initiating antipsychotic treatment. The incidence of akathisia varies depending on the type of antipsychotics administered. Haloperidol showed the greatest incidence of akathisia. Among SGAs, risperidone and aripiprazole (pro-akathisic) are associated with a higher rate of akathisia than olanzapine and quetiapine (non-akathisic). The type of antipsychotic (pro-/non-akathisic), need for hospitalization, and a more severe symptomatology at intake (total score on BPRS at baseline) seem to predict the development of acute akathisia. Further studies are needed to verify risk factors in the development of acute akathisia as well as to study their clinical impact at medium and long terms.

References

American Psychiatric Association (APA) (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington [DSM-V]

Amr M, Lakhan SE, Sanhan S, Al-Rhaddad D, Hassan M, Thiabh M, Shams T (2013) Efficacy and tolerability of quetiapine versus haloperidol in first-episode schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial. Int Arch Med 6(1):47

Andreasen NC (1983) The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City: University of Iowa

Andreasen NC (1984) The Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Iowa City: University of Iowa

Atkins M, Burgess A, Bottomley C, Riccio M (1997) Chlorpromazine equivalents: a consensus of opinion for both clinical and research applications. Psychiatr Bull 21:224–226

Barnes TR (1989) A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry 154:672–676

Barnes TR, Halstead SM, Little PW. Relationship between iron status and chronic akathisia in an in-patient population with chronic schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry, 1992;791–6.

Basu R, Brar JS (2006) Dose-dependent rapid-onset akathisia with aripiprazole in patients with schizoaffective disorder. Neuropsychoatr Dis Treat 2(2):241–243

Berardi D, Giannelli A, Barnes TR (2000) Clinical correlates of akathisia in acute psychiatric inpatients. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 15(4):215–219

Berna F et al (2015) Akathisia: prevalence and risk factors in a community-dwelling sample of patients with schizophrenia. Results from the FACE-SZ dataset. Schizophr Res 169(1–3):255–261

Caseiro O, Pérez-Iglesias R, Mata I, Martínez-García O, Pelayo-Terán JM, Tabarés-Seisdedos R, Ortiz-Garcia de la Foz V et al (2012) Predicting relapse after a first episode of non-affective psychosis: a three-year follow-up study. J Psychiatr Res 46(8):1099–1105

Cematbasoglu E, Schultz SK, Andreasen NC (2001) The relationship of akathisia with suicidality and depersonalization among patients with schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Clin Nerosci 13(3):336–341

Chong SA, Mythily, Remington G (2002) Clinical characteristics and associated factors in antipsychotic-induced akathisia of Asian patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 59(1):67–71

Cotter PE, O’Keeffe ST (2007) Improvement in neuroleptic-induced akathisia with intravenous iron treatment in a patient with iron deficiency. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 78(5):548

Crespo-Facorro B, Pérez-Iglesias R, Mata I, Ramírez-Bonilla M, Martínez-García O, Llorca J, Vázquez-Barquero J (2006) A practical clinical trial comparing haloperidol, risperidone and olanzapine for the acute treatment of first-episode nonaffective psychosis. Psychopharmacology 219:225–233

Crespo-Facorro B, Ortiz V, Mata I, Ayesa-Arriola R, Suárez-Pinilla P, Valdizan E, Martínez-García O, Pérez-Iglesias R (2014) Treatment of first-episode non-affective psychosis: a randomized comparision of aripiprazole, quetiapine and ziprasidone. Psychopharmacology 219:225–233

Danivas V, Venkatasubramanian G (2013) Current perspectives on chlorpromazine equivalents: comparing apples and oranges! Indian J Psychiatry 55(2):207–208

De León J, Díaz FJ, Aguilar MC, Jurado D, Gurpegui M (2006) Does smoking reduce akathisia? Testing a narrow version of the self-medication hypothesis. Schizophr Res 86(1–3):256–268

Espi-Forcen F, Matsoukas K, Alice Y (2016) Antipsychotic-induced akathisia in delirium: a systematic review. Palliat SupportCare 14:77–84

Flemenbaum A, Zimmermann RL (1973) Inter- and intra-rater reliability of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep 32:783–792

Gafoor R, Landau S, Craig TK, Elanjithara T, Power P, McGuire P (2010) Esquire trial: efficacy and adverse effects of quetiapine versus risperidone in first-episode schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol 30(5):600–606

Green AI, Lieberman JA, Hamer RM, Glick ID, Gur RE, Kahn RS, McEvoy JP et al (2006) Olanzapina and haloperidol in first episode psychosis: two-year data. Schizophr Res 86(1–3):234–243

Haddad PM, Das A, Keyhani S, Chaudhry IB (2012) Antipsychotic drugs and extrapyramidal side effects in first episode psychosis: a systematic review of head-head comparisons. J Psychopharmacol 26(5 Suppl):5–26

Hansen L (2001) A critical review of akathisia, and its possible association with suicidal behavior. Hum Psychopharmacol 16:495–505

Hansen LK, Nausheen B, Hart D, Kingdon D (2013) Movement disorders in patients with schizophrenia and a history of substance abuse. Hum Psychopharmacol 28(2):192–197

Hirose S (2003) The causes of underdiagnosing akathisia. Schizophr Bull 29(3):547–558

Hofmann M, Seifritz E, Botschev C, Kräuchi K, Müller-Spahn F (2000) Serum iron and ferritin in acute neuroleptic akathisia. Psychiatry Res 93(3):201–207

Janno S, Holi MM, Tuisku K, Wahlbeck K (2005) Actometry and Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale in neuroleptic-induced akathisia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 15(1):39–41

Kim JH, Byun HJ (2007) Association of subjective cognitive dysfunction with akathisia in patients receiving stable doses of risperidone or haloperidol. J Clin Pharm Ther 32(5):461–467

Kim JH, Byun HJ (2010) The relationship between akathisia and subjective tolerability in patients with schizophrenia. Int J Neurosci 120:507–511

Kuloglu M, Atmaca M, Ustündag B, Canatan H, Gecici O, Tezcan E (2003) Serum iron levels in schizophrenic patients with or without akathisia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 13(2):67–71

Kumar S, Sachdev PS (2009) Akathisia and second-generation antipsychotic drugs. Curr Opin Psychiatry 22:293–299

Lee EH, Hui CL, Lin JJ, Ching EY, Chang WC, Chan SK, Chen EY (2016) Quality of life and functioning in first-episode psychosis Chinese patients with different antipsychotic medications. Early Interv Psychiatry 10(6):535–539

Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, Mavridis D, Örey D, Richter F et al (2013) Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 382:951–962

Lieberman JA, Tollefson G, Tohen M, Green AI, Gur RE, Kahn R, McEvoy J et al (2003) Comparative efficacy and safety of atypical and conventional antipsychotic drugs in first-episode psychosis: a randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine versus haloperidol. Am J Psychiatry 160(8):1396–1404

Loonen AJ, Stahl SM (2011) The mechanism of drug-induced Akathsia. CNS Spectr 16(1):7–10

Maat A, Fouwels A, de Haan L (2008) Cocaine is a major risk factor for antipsychotic induced akathisia, parkinsonism and dyskinesia. Psychopharmacol Bull 41(3):5–10

Mathews M, Gratz S, Adetunji B, George V, Mathews M, Basil B (2005) Antipsychotic-induced movement disorders: evaluation and treatment. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2(3):36–41

Miller CH, Hummer M, Oberbauer H, Kurtzhaler I, DeCol C, Fleischhacker WW (1997) Risk factors for the development of neuroleptic induced akathisia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 7(1):51–55

Miller DD, Caroff SN, Davis SM, Rosenheck RA, McEvoy JP, Saltz BL, Riggio S et al (2008) Extrapyramidal side-effects of antipsychotics in a randomised trial. Br J Psychiatry 193(4):279–288

Möller HJ, Riedel M, Jäger M, Wickelmaier F, Maier W, Kühn KU, Buchkremer G et al (2008) Short- term treatment with risperidone or haloperidol in first-episode schizophrenia: 8-week results of a randomized controlled trial within the German Research Network on Schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 11(7):985–997

O’Loughlin V, Dickie AC, Ebmeier KP (1991) Serum iron and transferrin in acute neuroleptic induced akathisia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 54(4):363–364

Opjordsmoen S, Melle I, Friis S, Haarh U, Johannessen JO, Larsen TK, Rund BR et al (2009) Stability of medication in early psychosis: a comparison between second-generation and low-dose first-generation antipsychotics. Early Interv Psychiatry 3(1):58–65

Pappa S, Dazzan P (2009) Spontaneous movement disorders in antipsychotic-naïve patients with first-episode psychoses: a systematic review. Psychol Med 39(7):1065–1076

Pelayo-Terán JM, Pérez-Iglesias R, Ramírez-Bonilla M, González-Blanch C, Martínez-García O, Pardo-García G, Rodríguez-Sánchez JM et al (2008) Epidemiological factors associated with treated incidence of first-episode non-affective psychosis in Cantabria: insights from the Clinical Programme on Early Phases of Psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry 2(3):178–187

Peluso MJ, Lewis SW, Barnes TR (2012) Extrapyramidal motor side-effects of first- and second-generation antipsychotic drugs. Br J Psychiatry 200(5):387–392

Peralta V, Cuesta MJ (2011) Neuromotor abnormalities in neuroleptic-naive psychotic patients: antecedents, clinical correlates, and prediction of treatment response. Compr Psychiatry 52(2):139–145

Potvin S, Pampoulova T, Macini-Marie A, Lipp O, Bouchard RH, Stip E (2006) Increased extrapyramidal symptoms in patients with schizophrenia and a comorbid substance use disorder. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 77(6):796–798

Potvin S, Blanchet P, Stip E (2009) Substance abuse is associated with increased extrapyramidal symptoms in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 113:181–188

Poyurovsky M (2010) Acute antipsychotic-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry 196:89–91

Robinson DG, Woerner MG, Delman HM, Kane JM (2005) Pharmacological treatments for first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 31(3):705–722

Robinson DG, Gallego JA, John M, Petrides G, Hassoun Y, Zhang JP, López L et al (2015) A randomized comparison of aripiprazole and risperidone for the acute treatment of first-episode schizophrenia and related disorders: 3-month outcomes. Schizophr Bull 41(6):227–1236

Sachdev P (1995) The epidemiology of drug-induced akathisia: part I. Acute akathisia. Schizophr Bull 21(3):431–449

San L, Arranz B, Pérez V, Safont G, Corripio I, Ramírez N et al (2012) One-year, randomized, open trial comparing olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone and ziprasidone effectiveness in antipsychotic-naive patients with a first-episode psychosis. Psychiatry Res 200:693–701

Seemüller FS, Mayr A, Musil R, Jäger M, Maier W, Klingenberg S, Heuser I et al (2012) Akathisia and suicidal ideation in first episode schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol 32(5):694–698

Soni SD, Tench D, Routledge RC (1993) Serum iron abnormalities in neuroleptic-induced akathisia in schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry 163:669–672

Stahl SM (2013) Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology. Neuroscientific basis and practical applications, 4th edn. Cambridge Medicine

Sundram S, Lambert T, Piskulic D (2008) Acculturation is associated with the prevalence of tardive dyskinesia and akathisia in community-treated patients with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 117(6):474–478

Thomas JE, Caballero J, Harrington CA (2015) The incidence of akathisia in the treatment of schizophrenia with aripiprazole, asenapine and lurasidone: a meta-analysis. Curr Neuropharmacol 13(5):681–691

Wood SW (2003) Chlorpromazine equivalent doses for the newer atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry 64(6):663–667

Zhang JP, Gallego JA, Robinson DG, Malhotra AK, Kane JM, Correll CU (2013) Efficacy and safety of individual second-generation vs. first-generation antipsychotics in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 16(6):1205–1218

Zhornitsky S, Stip E, Pampoulova T, Rizkallah E, Lipp O, Bentaleb LA, Chiasson JP, Potvin S (2010) Extrapyramidal symptoms in substance abusers with and without schizophrenia and in nonabusing patients with schizophrenia. Mov Disord 25(13):2188–2194

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the PAFIP researchers who helped with data collection and specially acknowledge Gema Pardo. Finally, we should also like to thank the participants and their families for enrolling in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Prof. Crespo-Facorro has received speaking honoraria (advisory board and educational lectures) and travel expenses from Otsuka, Lundbeck and Johnson & Johnson in the last three years. Dr. Juncal-Ruiz has received travel expenses from Lundbeck in the last three years. Drs. Ramirez-Bonilla and Suarez-Pinilla have received travel expenses from Lundbeck and Johnson & Johnson in the last three years. Prof. Tabares-Seisdedos, Dr. Gomez-Arnau, Mrs. Martinez-Garcia, Mr. Ortiz-Garcia and Mr. Neergaard report no additional financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article.

Funding

The present study was carried out at the Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla, University of Cantabria, Santander, Spain, under the following grant support: Instituto de Salud Carlos III PI020499, PI050427, PI060507, Plan Nacional de Drugs Research Grant 2005-Orden sco/3246/2004, SENY Fundació Research Grant CI 2005–0308007 and Fundación Marqués de Valdecilla API07/011. Unrestricted educational and research grants from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Johnson & Johnson provided support to PAFIP activities. No pharmaceutical industry has participated in the study concept and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the results, and drafting the manuscript. The study, designed and directed by B C-F, conformed to international standards for research ethics and was approved by the local institutional review board.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Juncal-Ruiz, M., Ramirez-Bonilla, M., Gomez-Arnau, J. et al. Incidence and risk factors of acute akathisia in 493 individuals with first episode non-affective psychosis: a 6-week randomised study of antipsychotic treatment. Psychopharmacology 234, 2563–2570 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-017-4646-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-017-4646-1