Abstract

Summary

Fall risk does not significantly impact on the efficacy of the bisphosphonate clodronate in reducing the incidence of fracture.

Introduction

The debate about the efficacy of skeletal therapies on fracture risk in women at increased risk of falling continues. We determined whether fall risk impeded the efficacy of clodronate to reduce osteoporotic fracture incidence.

Methods

This is a post hoc analysis of a 3-year placebo-controlled study of bisphosphonate clodronate involving 5,212 women aged 75 years or more. At entry, self-reported multiple falls in the previous month and ability to rise from a chair were documented. Their interaction with treatment efficacy was examined using Poisson regression.

Results

Oral doses of clodronate at 800 mg daily reduced osteoporotic fracture incidence by 24% (hazard ration (HR) 0.76, 95% confidence interval 0.63–0.93). The efficacy was similar in women with recent multiple falls compared to those without (HR 0.61 vs. 0.77, p value for interaction >0.30) or impaired ability in rising compared to those with no impairment (HR 0.79 vs. 0.74, respectively; p value > 0.30).

Conclusion

Fall risk does not significantly impact on the anti-fracture efficacy of clodronate. If confirmed with other agents, fall risk may be incorporated into risk assessment tools designed to target skeletal therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The World Health Organisation has recently developed a sophisticated algorithm for the estimation of 10-year fracture probability of individuals [1–4]. This algorithm (the FRAX® tool; www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX) computes fracture probabilities with or without the input of femoral neck bone mineral density (BMD), but its clinical utility, like that of other clinical risk algorithms, is dependent on the efficacy of treatments, predominantly bisphosphonates, in those identified to be at high risk. Fall risk is an important contributor to fracture risk prediction [5–7] but is currently not included in the FRAX algorithm. This reflects in part a paucity of appropriate information in the cohorts used to derive the FRAX tool and also a lack of consensus about the appropriate intervention that might be indicated in those deemed to be at high risk. Whilst several physical intervention strategies have been shown to reduce the incidence of falls, at least in the short term, the effect of such interventions to significantly reduce fracture incidence remains unproven [7, 8]. Furthermore, the efficacy of treatments targeted at the skeleton, such as the bisphosphonates, to reduce fracture risk in patients with fall-related risk factors remains controversial. Most notably, the failure of risedronate to significantly reduce non-vertebral and hip fracture risk in a subgroup of elderly women recruited on the basis of risk factors largely related to fall risk [9] suggested that bisphosphonate therapy may not be appropriate in such patients.

We have previously shown that the bisphosphonate clodronate decreases osteoporotic fracture risk in elderly women [10] and is effective in those identified to be at high risk using the FRAX tool [11]. In this analysis, we wished to examine the interaction between reported fall history and a surrogate marker of fall risk, the sit-to-stand test [12], on fracture risk reduction in the same prospective study to determine if fall risk impacted on bisphosphonate efficacy.

Participants and methods

The study has been described in detail elsewhere [10]. Briefly, this was a double-blind, prospective, randomised, placebo-controlled, single-centre study in elderly community-dwelling women aged 75 years or more. Participants were recruited randomly from general practice lists and did not need to have proven osteoporosis nor any other known risk factors for fracture. The study had the prior approval of the South Sheffield Research Ethics Committee.

All baseline assessments were carried out during a single clinic visit between 1996 and 1999 with follow-up visits thereafter conducted in the community by a team of study nurses at 6-month intervals to undertake collection of fracture data, adverse events and hospitalisations as well as to collect and dispense study medication.

Each participant underwent a detailed and comprehensive assessment of her general health, fracture history and a number of measurements of bone density, muscle strength and postural stability. Bone mineral density was measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry at the hip using a Hologic QDR4500 Acclaim densitometer. None of the results of the baseline assessments of fracture risk, including bone density values, were communicated to the participants.

Recent fall history and the sit-to-stand test

Physical examinations comprised a number of measures of muscle strength and postural stability including the sit-to-stand test from a chair. The latter measure was not timed but entailed the study nurse grading the individual’s ability into one of three categories: unable to stand, difficulty in sit-to-stand and no difficulty. In the present analysis, those with no difficulty in standing were compared to those with difficulty or inability to stand (the combination is termed impaired ability). In addition, all participants were also interviewed using the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys’ (UK) disability survey instrument [13]. Briefly, this assesses disabilities of locomotion, reaching/stretching, dexterity, vision, hearing, behaviour, communication, disfigurement, bladder/bowel control, consciousness, intellectual function, independent daily activities and personal care. Within the locomotion domain, we were able to identify those who reported multiple recent falls defined as more than one fall in the previous month.

All reported incident fractures were confirmed by hospital notes, discharge/GP letters, copies of radiographic reports or review of radiographs if necessary. Only verified fractures were included in statistical analyses and were defined as “clinical fractures” as they had presented symptomatically and triggered radiological investigation. The current analysis is confined to incident osteoporotic clinical fractures (excludes high-trauma fractures and those of the skull, nose, face, hand, finger, feet, toe, ankle and patella fractures regardless of trauma level) [14].

Validation of fall history and impaired ability in sit-to-stand test as markers of increased fall risk

This was undertaken in three ways; firstly, we examined the relationship between the two variables at study entry; secondly, we looked at the relationship between both and diseases that were specifically enquired about at study entry. These included diseases known to be associated with an increased risk of falls and/or fracture such as previous stroke [15, 16], Parkinson’s disease [17, 18], diabetes mellitus (insulin dependent and non-insulin dependent, separately) [19], hypo- and hyper-thyroidism and osteoarthritis [20]. Finally, we examined how baseline falls or impaired ability to stand predicted future falls, particularly those not associated with fracture. During follow-up, all hospital admissions as a result of a fall, including those not associated with fracture, were recorded as serious adverse events and these admissions were verified from hospital records, discharge summaries or GP letters.

Following randomisation, the women received either clodronate at 800 mg daily (two Bonefos® 400-mg tablets once daily or one tablet twice daily) or an identical placebo. The intervention was continued for 3 years and concomitant calcium and vitamin D supplementation was not given.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were undertaken on an intent-to-treat basis so that all osteoporotic fractures were included in the analyses regardless of whether the women were taking study medication or not.

The baseline characteristics of those women with reported multiple falls in the previous month or impaired sit-to-stand test (defined as difficulty or inability) were compared by analysis of variance or chi-square tests where appropriate. Poisson regression [21] was used to examine the interaction between the zero–one variable recent fall (or impaired stand-up test) and the zero–one variable clodronate treatment. Briefly, a Poisson model was used to study the relationship between age, the time since baseline, treatment, falls/stand on the one hand and on the other hand the risk of fracture. The hazard function was assumed to be exp(β 0 + β 1 · current time from baseline + β 2 · current age + β 3 · stand/falls + β 4 · treatment + β 5 · stand/falls · treatment). The beta coefficients reflect the importance of the variables as in a logistic or Cox model, and β x = 0 denotes that the corresponding variable does not contribute to fracture risk. Thus, a beta coefficient of zero for the interaction (product) (β 5) means that the efficacy of clodronate is the same independently of the risk variable (standing or falls).

Results

The total follow-up during the 3-year study was similar in both study groups (7,761 and 7,628 person-years for placebo and clodronate, respectively), with a median treatment exposure of 2.9 years for both treatment groups. There were no major differences between women assigned to clodronate and those assigned to placebo with respect to the reasons for discontinuation of the study.

Baseline comparisons

At baseline, data on self-reported falls and/or impaired sit-to-stand tests were available in 92.6% and 99.9% of women, respectively. Amongst those with captured data, self-reported multiple falls in the last month were documented in 4% of women, and impaired sit-to-stand was recorded in 31%. Women with self-reported multiple falls were significantly older but did not differ significantly in the prevalence of other FRAX risk factors from those not reporting such falls (Table 1). Impaired ability in the sit-to-stand test was associated with increased reports of multiple falls, older age, a higher prevalence of prior fractures, more frequent glucocorticoid exposure and self-reported rheumatoid arthritis (Table 1). Importantly, however, impaired ability in rising from a chair was associated with a higher body mass index and femoral neck BMD expressed as the Z-score (Table 1). The prevalence values of baseline medical conditions in those women reporting recent falls or experiencing difficulty in the sit-to-stand tests are shown in Table 1. Whilst the prevalence of some of these diseases was low, it was still possible to observe an association between them and the reported falls or impaired ability to stand.

The baseline characteristics of women randomly assigned to clodronate treatment were similar to those in the placebo group including the proportions of women reporting previous multiple falls (4% vs. 3%, respectively; p > 0.30) and demonstrating impaired sit-to-stand (32 vs. 31%, p > 0.30; other data not shown).

Relationships between fall history, sit-to-stand and incident falls and fractures

During the 3-year intervention period, 272 women were admitted to hospital for fall-related injuries, excluding those admitted with an associated fracture. A baseline reported history of multiple falls in the previous month was associated with an increased risk of subsequent hospital admission with a serious fall (excluding falls associated with fractures; 12.1% vs. 4.7%, odds ratio (OR) 2.78, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.73–4.47; Fig. 1). Similarly, impaired sit-to-stand ability was also significantly associated with a higher future risk of hospital admission due to a serious fall but without fracture (8.3% vs. 3.8%, OR 2.30, 95% CI 1.80–2.94; Fig. 1).

Incident osteoporotic fractures were recorded in 419 women. Poisson regression demonstrated that falling was associated with an increased risk of future osteoporotic fracture, though this did not reach statistical significance (hazard ratio (HR) 1.49, 95% CI 0.95–2.33, p = 0.086). A similar relationship was observed for incident hip fractures though the confidence intervals were much wider (HR 1.17 0.37–3.74). Impaired ability in the sit-to-stand test was associated with a significant increase in the risk of future osteoporotic fracture (HR 1.58, 95% CI 1.29–1.93, p < 0.001) and the risk of hip fracture (HR 2.04 1.28–3.25, p = 0.003; Fig. 2). Recent multiple falls and impaired ability in the sit-to-stand test remained significant predictors of future osteoporotic fracture independent of the 10-year probability of fracture estimated by FRAX, with femoral neck BMD included (HR 1.93 1.21–3.07, p = 0.006 and HR 1.38 1.09–1.75, p = 0.007, respectively).

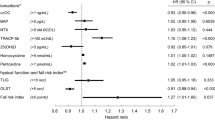

Impact of impaired sit-to-stand on efficacy of clodronate to reduce osteoporotic fracture risk

Oral clodronate at 800 mg daily was associated with 24% reduction in osteoporotic fracture incidence (HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.63–0.93; Fig. 3). The efficacy of clodronate was similar in women with a self-reported history of recent multiple falls compared to those without (HR, 95% CI 0.61, 0.24–1.52 vs. 0.77, 0.63–0.95; p value for interaction >0.30; Fig. 3). Similar efficacy of clodronate was also observed in women with impaired ability in the sit-to-stand test compared to those with no difficulty in rising (HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.58–1.06 vs. 0.74 and 0.57–0.96, respectively; p value for interaction with treatment >0.30; Fig. 3).

Impact of clodronate on the incidence of osteoporotic fractures over 3 years of treatment in women included in this analysis with or without a recent history of multiple falls or impaired ability in the sit-to-stand test. The horizontal line represents the overall efficacy (hazard ratio) for clodronate on osteoporotic fractures

Discussion

Falls are a major cause of disability in older people. One third of those aged 65 years or over who live in the community fall each year and this figure rises to 50% in those cared for in institutions [7]. Approximately 5% of such falls result in a non-vertebral fracture and up to 1% are associated with hip fractures. Approximately 14,000 people a year die in the UK as a result of an osteoporotic hip fracture [22]. The need to successfully reduce serious injury, including fractures, in elderly women at increased risk of falling is a widely established goal of management in many guidelines [23, 24]. However, whilst many studies have addressed strategies to successfully reduce fall risk, to date, none of these, either individually or in meta-analyses, have shown convincing reductions in the incidence of fracture [7, 8]. In contrast, many placebo-controlled studies of skeletally targeted therapies have shown significant reductions in fracture risk at both vertebral and non-vertebral sites, including studies of bisphosphonates, strontium ranelate and teriparatide [25–28]. Recruitment to these studies has largely been on the basis of low bone mineral density and/or prior osteoporotic fracture, but it is also important to note that they did not exclude patients with increased fall risk at study entry. However, most did not document baseline fall history and so have been unable to report the interaction between fall risk and anti-fracture efficacy. The results of our analysis suggest that the efficacy of the bisphosphonate clodronate is not influenced by fall risk, defined by a recent history of multiple falls or as impaired ability in standing up from a chair.

The sit-to-stand test [29, 30] has been widely studied as a marker of postural control, lower extremity strength and proprioception. Several studies have shown it to be associated with or predictive of increased fall risk in older adults [12, 31–33]. The ability of subjects to perform the sit-to-stand test has been captured in a number of ways ranging from subjective to timed assessments of multiple tests [30, 34]. We chose to make a subjective assessment in the present study, and it was thus important to validate the observed test results against recognised clinical correlates. The performance of sit-to-stand in our study was comparable to that in previous studies in terms of its association with diseases causing impaired mobility, reports of recent falls and the future incidence of falls, including those not associated with fracture.

Our observation of no interaction between fall risk and the efficacy of clodronate is in contrast to the apparent lack of efficacy of the bisphosphonate risedronate on hip and non-vertebral fractures in women aged 80 years and older recruited on the basis of non-skeletal clinical risk factors [9]. The latter risk factors included difficulty standing from a sitting position, a poor tandem gait, a fall-related injury during the previous year, a low psychomotor score (considered to indicate an increased risk of falling), current smoking or smoking during the previous 5 years, a maternal history of hip fracture, a previous hip fracture and a hip axis length of 11.1 cm or greater. Measurements of femoral neck BMD were only undertaken at study entry in approximately one third of these elderly women. Risedronate was associated with a non-significant 20% reduction in hip fracture risk and 10% decrease in non-vertebral fracture risk in this study population [9]. This study has a number of major limitations that may have impacted on the outcome. Firstly, though recruited on the basis of clinical risk factors, the individual risk factors were not recorded in sufficient detail to allow an examination of treatment efficacy with the individual factors. In the risedronate study, unlike our study, all participants received concomitant calcium and vitamin D supplementation which also may have decreased the incidence of falls in both groups, leading to a further reduction in the power of the study. However, data for the impact of calcium and/or vitamin D supplementation on fall and fracture risk remain inconclusive [35, 36]. More importantly perhaps, the loss to follow-up in the risedronate study was quite substantial—complete follow-up data were only available in just over half (58%) of the study participants and those lost to follow-up had a higher prevalence of risk factors for fracture including being older, lighter and smoking more [9]. All of these factors contribute to uncertainty about the study outcome in this elderly cohort. In our study, complete follow-up data were available in 82% of the cohort at 3 years and this rises to 90% if deaths are taken into account.

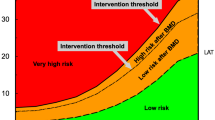

If patients who fall respond to a pharmacologic skeletal intervention as well as those that do not fall, as suggested in the present study, this would have a number of implications for clinical practise. For example, if an individual is identified at high risk on the basis of clinical risk factors alone using the FRAX® tool and that individual has a high fall risk, intervention with a bisphosphonate or other skeletal treatment would be warranted as efficacy is similar in the presence of fall risk. This would not of course exclude simultaneous intervention strategies to reduce fall risk, but it would seem inappropriate to use only the latter strategy and ignore the use of bone-targeted therapy as suggested by some [37].

In addition, account should be taken of a history of falls in the interpretation of the FRAX result. Intervention thresholds will increasingly be based on fracture probabilities [1, 38, 39], so that a given fracture probability that lies somewhat below the intervention threshold may identify a patient in whom treatment should be considered.

We recognise that it is important to confirm our findings in independent studies. If they are confirmed and if fall risk gives information independently of the other FRAX risk variables, then fall risk should be incorporated into future algorithms. This will, however, demand information on fall risk using a standardised instrument as well as the risk variables currently used in multiple-population-based cohorts.

References

Fujiwara S, Nakamura T, Orimo H, Hosoi T, Gorai I, Oden A, Johansson H, Kanis JA (2008) Development and application of a Japanese model of the WHO fracture risk assessment tool (FRAX). Osteoporos Int 19(4):429–435

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Johansson H, McCloskey E (2008) FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporos Int 19(4):385–397

Dawson-Hughes B, Tosteson AN, Melton LJ 3rd, Baim S, Favus MJ, Khosla S, Lindsay RL (2008) Implications of absolute fracture risk assessment for osteoporosis practice guidelines in the USA. Osteoporos Int 19(4):449–458

Tosteson AN, Melton LJ 3rd, Dawson-Hughes B, Baim S, Favus MJ, Khosla S, Lindsay RL (2008) Cost-effective osteoporosis treatment thresholds: the United States perspective. Osteoporos Int 19(4):437–447

Sambrook PN, Cameron ID, Chen JS, Cumming RG, Lord SR, March LM, Schwarz J, Seibel MJ, Simpson JM (2007) Influence of fall related factors and bone strength on fracture risk in the frail elderly. Osteoporos Int 18(5):603–610

Geusens P, Milisen K, Dejaeger E, Boonen S (2003) Falls and fractures in postmenopausal women: a review. J Br Menopause Soc 9(3):101–106

Gillespie LD, Gillespie WJ, Robertson MC, Lamb SE, Cumming RG, Rowe BH (2003) Interventions for preventing falls in elderly people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4):CD000340

Gates S, Fisher JD, Cooke MW, Carter YH, Lamb SE (2008) Multifactorial assessment and targeted intervention for preventing falls and injuries among older people in community and emergency care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj 336(7636):130–133

McClung MR, Geusens P, Miller PD, Zippel H, Bensen WG, Roux C, Adami S, Fogelman I, Diamond T, Eastell R, Meunier PJ, Reginster JY (2001) Effect of risedronate on the risk of hip fracture in elderly women. Hip Intervention Program Study Group. N Engl J Med 344(5):333–340

McCloskey EV, Beneton M, Charlesworth D, Kayan K, deTakats D, Dey A, Orgee J, Ashford R, Forster M, Cliffe J, Kersh L, Brazier J, Nichol J, Aropuu S, Jalava T, Kanis JA (2007) Clodronate reduces the incidence of fractures in community-dwelling elderly women unselected for osteoporosis: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized study. J Bone Miner Res 22(1):135–141

McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Oden A, Vasireddy S, Kayan K, Pande K, Jalava T, Kanis JA (2008) Ten year fracture probability identifies women who will benefit from clodronate therapy—additional results from a placebo-controlled, randomised clinical trial. Osteoporos Int 20:811–817

Nevitt MC, Cummings SR, Kidd S, Black D (1989) Risk factors for recurrent nonsyncopal falls. A prospective study. JAMA 261:2663–2668

Martin J, White A (1988) The prevalence of disability among adults. OPCS surveys of disability in Great Britain Report 1. OPCS Social Survey Division HMSO, London

Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, Jonsson B, de Laet C, Dawson A (2001) The burden of osteoporotic fractures: a method for setting intervention thresholds. Osteoporos Int 12(5):417–427

Melton LJ 3rd, Brown RD Jr, Achenbach SJ, O'Fallon WM, Whisnant JP (2001) Long-term fracture risk following ischemic stroke: a population-based study. Osteoporos Int 12(11):980–986

Ramnemark A, Nilsson M, Borssen B, Gustafson Y (2000) Stroke, a major and increasing risk factor for femoral neck fracture. Stroke 31(7):1572–1577

Johnell O, Melton LJ 3rd, Atkinson EJ, O'Fallon WM, Kurland LT (1992) Fracture risk in patients with parkinsonism: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Age Ageing 21(1):32–38

Taylor BC, Schreiner PJ, Stone KL, Fink HA, Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Bowman PJ, Ensrud KE (2004) Long-term prediction of incident hip fracture risk in elderly white women: study of osteoporotic fractures. J Am Geriatr Soc 52(9):1479–1486

Schwartz AV, Sellmeyer DE, Ensrud KE, Cauley JA, Tabor HK, Schreiner PJ, Jamal SA, Black DM, Cummings SR (2001) Older women with diabetes have an increased risk of fracture: a prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86(1):32–38

Arden NK, Nevitt MC, Lane NE, Gore LR, Hochberg MC, Scott JC, Pressman AR, Cummings SR (1999) Osteoarthritis and risk of falls, rates of bone loss, and osteoporotic fractures. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Arthritis Rheum 42(7):1378–1385

Breslow NE, Day NE (1987) Statistical methods in cancer research, vol. II. IARC scientific publications no. 32. IARC, Lyon, pp 131–135

Department of Health (2001) National service framework for older people. London, Department of Health

American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Panel on Falls Prevention (2001) Guideline for the prevention of falls in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 49(5):664–672

National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2004) Falls: the assessment and prevention of falls in older people. Clinical guideline 21. NICE, London

Kanis JA, Brazier JE, Stevenson M, Calvert NW, Lloyd Jones M (2002) Treatment of established osteoporosis: a systematic review and cost–utility analysis. Health Technol Assess 6(29):1–146

Reginster JY, Seeman E, De Vernejoul MC, Adami S, Compston J, Phenekos C, Devogelaer JP, Curiel MD, Sawicki A, Goemaere S, Sorensen OH, Felsenberg D, Meunier PJ (2005) Strontium ranelate reduces the risk of nonvertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: Treatment of Peripheral Osteoporosis (TROPOS) study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90(5):2816–2822

Neer RM, Arnaud CD, Zanchetta JR, Prince R, Gaich GA, Reginster JY, Hodsman AB, Eriksen EF, Ish-Shalom S, Genant HK, Wang O, Mitlak BH (2001) Effect of parathyroid hormone (1-34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 344(19):1434–1441

Black DM, Delmas PD, Eastell R, Reid IR, Boonen S, Cauley JA, Cosman F, Lakatos P, Leung PC, Man Z, Mautalen C, Mesenbrink P, Hu H, Caminis J, Tong K, Rosario-Jansen T, Krasnow J, Hue TF, Sellmeyer D, Eriksen EF, Cummings SR (2007) Once-yearly zoledronic acid for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 356(18):1809–1822

Csuka M, McCarty DJ (1985) Simple method for measurement of lower extremity muscle strength. Am J Med 78(1):77–81

Whitney SL, Wrisley DM, Marchetti GF, Gee MA, Redfern MS, Furman JM (2005) Clinical measurement of sit-to-stand performance in people with balance disorders: validity of data for the Five-Times-Sit-to-Stand Test. Phys Ther 85(10):1034–1045

Campbell AJ, Borrie MJ, Spears GF (1989) Risk factors for falls in a community-based prospective study of people 70 years and older. J Gerontol 44(4):M112–M117

Lipsitz LA, Jonsson PV, Kelley MM, Koestner JS (1991) Causes and correlates of recurrent falls in ambulatory frail elderly. J Gerontol 46(4):M114–M122

Szulc P, Claustrat B, Marchand F, Delmas PD (2003) Increased risk of falls and increased bone resorption in elderly men with partial androgen deficiency: the MINOS study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88(11):5240–5247

Bohannon RW (1995) Sit-to-stand test for measuring performance of lower extremity muscles. Percept Mot Skills 80(1):163–166

Porthouse J, Cockayne S, King C, Saxon L, Steele E, Aspray T, Baverstock M, Birks Y, Dumville J, Francis R, Iglesias C, Puffer S, Sutcliffe A, Watt I, Torgerson DJ (2005) Randomised controlled trial of calcium and supplementation with cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) for prevention of fractures in primary care. BMJ 330(7498):1003

Grant AM, Avenell A, Campbell MK, McDonald AM, MacLennan GS, McPherson GC, Anderson FH, Cooper C, Francis RM, Donaldson C, Gillespie WJ, Robinson CM, Torgerson DJ, Wallace WA (2005) Oral vitamin D3 and calcium for secondary prevention of low-trauma fractures in elderly people (Randomised Evaluation of Calcium Or vitamin D, RECORD): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 365(9471):1621–1628

Jarvinen TL, Sievanen H, Khan KM, Heinonen A, Kannus P (2008) Shifting the focus in fracture prevention from osteoporosis to falls. BMJ 336(7636):124–126

National Osteoporosis Foundation (2008) Clinician's guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. NOF, Washington, DC

Kanis JA, Burlet N, Cooper C, Delmas PD, Reginster JY, Borgstrom F, Rizzoli R (2008) European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 19(4):399–428

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Medical Research Council and Bayer Schering Pharma for funding the original study from which this analysis is derived.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Study funded by: Bayer Schering Pharma Oy, Helsinki, Finland and Medical Research Council, London, UK

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kayan, K., Johansson, H., Oden, A. et al. Can fall risk be incorporated into fracture risk assessment algorithms: a pilot study of responsiveness to clodronate. Osteoporos Int 20, 2055–2061 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-009-0942-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-009-0942-x