Abstract

Introduction

Our aim was to study any correlation between pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POP-Q) and ultrasound measurement of prolapse in women from a normal population and to identify the method with a stronger association with prolapse symptoms.

Methods

A cross-sectional study of 590 parous women responding to the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory was carried out. They were examined using POP-Q and transperineal ultrasound, and correlation was tested using Spearman’s rank test. Numerical measurements and significant prolapse (POP-Q ≥ 2 in any compartment or bladder ≥10 mm, cervix ≥0 mm or rectal ampulla ≥15 mm below the symphysis on ultrasound) were compared in symptomatic and asymptomatic women (Mann–Whitney U and Chi-squared tests).

Results

A total of 256 women had POP-Q ≥ 2 and 209 had significant prolapse on ultrasound. The correlation (rs) between POP-Q and ultrasound was 0.69 (anterior compartment), 0.53 (middle), and 0.39 (posterior), p < 0.01. Women with a “vaginal bulge” (n = 68) had greater descent on POP-Q and ultrasound in the anterior and middle compartments than asymptomatic women, p < 0.01. For women with a symptomatic bulge, the odds ratio was 3.8 (95% CI 2.2–6.7) for POP-Q ≥ grade 2 and 2.4 (95% CI 1.4–3.9) for prolapse on ultrasound. A sensation of heaviness (n = 90) and incomplete bladder emptying (n = 4) were more weakly associated with ultrasound (p = 0.03 and 0.04), and splinting (n = 137) was associated with POP-Q Bp, p = 0.02.

Conclusion

POP-Q and ultrasound measurement of prolapse had moderate to strong correlation in the anterior and middle compartments and weak correlation in the posterior compartment. Both methods were strongly associated with the symptom “vaginal bulge,” but POP-Q had a stronger association than ultrasound.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse is a common condition, and up to 20% of women in western countries undergo prolapse surgery during their lifetime [1]. The most specific symptom of prolapse is “seeing or feeling a vaginal bulge” [2]. Prolapse of the urinary bladder, bowel, and uterus can be associated with a wide range of other pelvic floor symptoms, such as incomplete bladder and bowel emptying, frequent urination, urinary and anal incontinence, and sexual dysfunction [2, 3]. The proportion of women feeling a vaginal bulge increases with increasing prolapse grade [4]. On the other hand, many women with smaller prolapses are asymptomatic, and there is no consensus about what is regarded as normal or abnormal support of the vaginal wall and uterus [5, 6]. Discrepancy between symptoms and clinical findings is common, and a general agreement is that only symptomatic prolapse needs treatment [7, 8].

Since 1996, the International Continence Society (ICS) pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POP-Q) system has been the gold standard for quantification of anatomical prolapse at clinical examination [3]. As anatomy does not always correlate with urinary and bowel symptoms, in some women, additional diagnostic tools are needed to make qualified decisions on conservative or surgical treatment. Imaging modalities such as defecography, cystography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been used to investigate the functional anatomy of the bladder and bowel in patients with pelvic floor disorders [9]. Transperineal ultrasound is a new alternative for the investigation of functional anatomy of the pelvic floor, and cut-offs have been suggested to define clinically relevant descent of the urinary bladder, cervix, and rectum in relation to the sensation of a vaginal bulge [10]. If ultrasound is a better diagnostic tool than POP-Q for women with prolapse, this should be offered as a complement to clinical examination for all women with prolapse symptoms. We are unaware of any previous study examining the correlation and agreement between POP-Q and ultrasound measurements in women from a normal population.

The aim of the present study was to explore any correlation and agreement between POP-Q and ultrasound measurements of prolapse in women from a normal population and to identify the method with a stronger association with prolapse symptoms.

Materials and methods

This was a secondary analysis of data collected in a cross-sectional study of parous women from a normal population who delivered their first child at Trondheim University Hospital, Norway between 1990 and 1997. A total of 847 women, who in 2013 had responded to a questionnaire regarding pelvic floor disorders, were invited to a clinical examination including POP-Q and transperineal ultrasound, regardless of symptoms and any previous gynecological surgery.

A Norwegian translation of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory Short-Form was part of the questionnaire [11]. Questions related to symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse were: “Do you usually experience pressure in the lower abdomen?”, “Do you usually experience heaviness or dullness in the lower abdomen?”, “Do you usually have a bulge or something falling out that you can see or feel in the vaginal area? “, “Do you usually experience a feeling of incomplete bladder emptying?”, “Do you ever have to push up in the vaginal area with your fingers to start or complete urination?”, “Do you feel you have not completely emptied your bowels at the end of a bowel movement?”, and “Do you usually have to push on the vagina or around the rectum to have a complete bowel movement?” A positive response to each question was recorded.

Study participants were examined in 2013–2014 by the first author (IV), who was blinded to the background characteristics and symptoms of prolapse and incontinence. Women were examined in the supine position after bladder and bowel emptying, with the hips and knees semi-flexed, and the lower abdomen covered to hide any surgical scars. Prolapse was quantified at maximum Valsalva according to the POP-Q system in 0.5-cm intervals, providing the staging of prolapse: stage 0 (no prolapse), stage 1 (distal-most part of the prolapse >1 cm above the hymen), stage 2 (distal-most part of the prolapse ≤1 cm above or below the hymen), stage 3 (distal-most part >1 cm below the hymen), and stage 4 (complete eversion of the vagina and uterus) [3]. Three POP-Q points were used for the analyses: the furthest descending point in the anterior vaginal wall (Ba), posterior vaginal wall (Bp), and the cervix (C) or vaginal vault in the case of previous hysterectomy. A prolapse stage 2 or more (POP-Q ≥ 2) in any compartment was counted as significant.

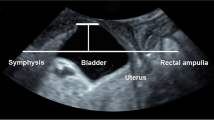

Acquisition of 3D/4D ultrasound volumes of the pelvic floor, lower urinary tract, and rectum was performed using a GE Voluson S6 ultrasound device, with a RAB 4- to 8-MHz abdominal three-dimensional (3D) probe, acquisition angle 85°, placed on the woman’s perineum and introitus. Volumes were acquired at rest, maximum pelvic floor contraction, and Valsalva maneuver. Off-line analysis of the ultrasound volumes was performed using 4DView software version 14 Ext. 0 (GE Medical Systems) by the second author (RGR) at an average of 30 months later, blinded to the women's demographics, POP-Q score, and symptoms. Two-dimensional images in the mid-sagittal plane were used for the evaluation of pelvic organ descent, as described previously [10]. Descent of the urinary bladder, cervix, and rectal ampulla was measured at Valsalva as the vertical distance (in millimeters) of the furthest descending part of each organ from a horizontal line drawn through the inferior–posterior margin of the symphysis pubis (Fig. 1). Positions above this line were recorded as positive and those below as negative values. A significant prolapse was defined as bladder descent ≥10 mm below the symphysis and the rectal ampulla ≥15 mm below the symphysis [10, 12]. Abnormal descent of the cervix on ultrasound has been suggested to be 15 mm above the symphysis [13], which corresponds to the POP-Q point C of −5. As C −5 is not counted as clinically relevant by most clinicians, we choose to use a cut-off of 0 mm, which corresponds to C −1 and prolapse grade 2 [12, 13]. Enterocele was diagnosed if the small bowel or omentum was seen at the level of the symphysis or below, and rectal intussusception was defined as an inversion of the anterior wall of the rectal ampulla into the anal canal [14, 15].

Descent measured by ultrasound as the organs’ vertical distance from the horizontal line drawn from the inferior border of the symphysis pubis (SP). The vertical distance from the horizontal line for the urinary bladder (UB), cervix (Cx), and rectal ampulla (RA) were a 32 mm, 31 mm, and 13 mm at rest and b −3 mm, 18 mm, and −8 mm at Valsalva (B)

Informed consent was obtained from all study participants. The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK midt 2012/666) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov with the identifier NCT01766193. No sample size calculations were performed for this study, as it was a secondary analysis, and sample size analysis was performed for the outcome measures for the parent study, where the aim was to study the prevalence of pelvic floor muscle trauma after different modes of delivery [16].

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Correlation between the numerical values of POP-Q and ultrasound was tested using Spearman’s rank correlation (rs); bladder position on ultrasound was tested against Ba, the rectal ampulla against Bp, and the cervix against C. rs = 0 implied no agreement, rs > 0.3 weak agreement, rs > 0.5 moderate agreement rs > 0.7 strong agreement, and rs = 1 perfect agreement. Then, the agreement between POP-Q ≥ 2 and significant prolapse on ultrasound was tested using Cohen’s kappa (κ). Venn diagrams were used to show the agreement among symptoms, POP-Q ≥ 2, and significant prolapse on ultrasound.

Then, median values for POP-Q and ultrasound measurements were calculated and compared in symptomatic and asymptomatic women using the Mann–Whitney U test for “seeing or feeling a vaginal bulge,” “sensation of pressure,” and “heaviness.” Only POP-Q Aa and urinary bladder on ultrasound were tested against “pushing to empty” and “sensation of incomplete bladder emptying,” and only POP-Q Bp and rectal ampulla on ultrasound were tested against “splinting” (having to push on the vagina or around the rectum to have a complete bowel movement) and “sensation of incomplete bowel emptying.”

Finally, Chi-squared test was used to calculate odds ratios (ORs) for POP-Q ≥ 2 and significant prolapse on ultrasound for women with the most specific prolapse symptom: “seeing or feeling a vaginal bulge.” In addition, intussusception on ultrasound was tested against “splinting” and “sensation of incomplete bowel emptying.” We used a p value <0.05 to define statistical significance for all analyses.

Results

Six-hundred and eight women answered the questionnaire and were examined using POP-Q and ultrasound. We included 590 women with complete datasets; 13 ultrasound volumes had not been stored properly, and 5 volumes were of poor image quality, (Supplementary material). Baseline characteristics and the prevalence of the main outcome variables are listed in Table 1. The women were significantly older than the background population from which they were recruited (47.9 years, p < 0.01), but other demographics and prevalence of prolapse symptoms were similar [17].

Correlation and agreement between the POP-Q and ultrasound are shown in Table 2. The strongest correlation and agreement were found in the anterior compartment and weakest in the posterior compartment. Figure 2 is a Venn diagram of the overlap between “seeing or feeling a vaginal bulge,” POP-Q ≥ 2 , and any significant prolapse on ultrasound. Four women with a sensation of bulge and POP-Q < 2 had the prolapse diagnosis verified on ultrasound; 3 in the posterior compartment, and 1 of the cervix. POP-Q was diagnostic for 16 symptomatic women who were missed on ultrasound diagnosis. Fifteen out of 68 women with bulge symptoms (22%) had no prolapse on ultrasound or POP-Q.

Venn diagram with data from 581 women with complete datasets demonstrating overlap between symptoms (“seeing or feeling a vaginal bulge”), prolapse in any compartment on clinical examination (pelvic organ prolapse quantification [POP-Q] Aa, C or Ba ≥ −1 cm) or ultrasound (urinary bladder ≥ 10 mm, cervix ≥ 0 mm or rectal ampulla ≥ 15 mm below the symphysis)

We found a highly significant difference between symptomatic and asymptomatic women in the anterior compartment and cervix for “seeing or feeling a vaginal bulge,” (Table 3). “Sensation of heaviness” (n = 90) and “incomplete bladder emptying” (n = 4) were more weakly associated with ultrasound (p = 0.03 and 0.04), and “splinting” (n = 137) was associated with POP-Q Bp, p = 0.02. For “sensation of pressure” (n = 96), “incomplete bladder emptying” (n = 196), and “incomplete bowel emptying” (n = 192), no difference between symptomatic and asymptomatic women was found.

For women “seeing or feeling a vaginal bulge” the ORs for POP-Q ≥ 2 and significant descent on ultrasound are listed in Table 4. Eighteen women were diagnosed with rectal intussusception on ultrasound, and 11 of them had splinting symptoms. The OR was 5.5 (95% CI 2.1–14.5) for intussusception on ultrasound for women with splinting symptoms. Seven women had enterocele diagnosed by ultrasound, and 3 of them had posterior wall prolapse on clinical examination.

Discussion

In this study of parous women from a normal population, the correlation and agreement between POP-Q and ultrasound was strongest for the anterior compartment and weakest for the posterior compartment. Both methods were strongly associated with the symptom “seeing or feeling a vaginal bulge,” but POP-Q was more strongly associated than ultrasound. The association was strongest when prolapse was diagnosed in the anterior compartment.

A similar correlation and agreement between ultrasound and POP-Q was found in previous studies in patient populations [12, 18]. Dietz et al. examined 825 women, but found weaker agreement for all compartments (anterior 75%, middle 69%, and posterior 63%) than our study [12]. In that study, more women had greater prolapses, and interpretation of ultrasound volumes could be difficult when the prolapse exceeded the level of the hymen. In our study, all POP-Q measurements were undertaken by one examiner, also eliminating any inter-rater disagreement for this parameter. Broekhuis et al. examined the correlation between ultrasound and POP-Q in 61 women and found a moderate correlation (rs = 0.58) only for the anterior compartment [18]. A likely explanation for the poorer correlation in the posterior compartment in all these studies is that a prolapse of the posterior vaginal wall at clinical examination is not synonymous with rectocele, and the clinical distinction between rectocele and enterocele is difficult. POP-Q is measured in relation to the introitus/perineum, and ultrasound in relation to the symphysis, and any perineal descent occurring at Valsalva could have a greater impact on measurements in the posterior than in the anterior and middle compartments.

The symptom with strongest correlation with POP-Q and ultrasound measurements of prolapse was “seeing or feeling a vaginal bulge.” This is also in agreement with existing literature [2]. For women “seeing or feeling a vaginal bulge,” the ORs were higher for POP-Q ≥ 2 than for prolapse on ultrasound for all three compartments, indicating that POP-Q is a better diagnostic tool than ultrasound. For both methods, the ORs were higher if prolapse was diagnosed in the anterior and middle compartments, implying that posterior compartment prolapse is less symptomatic. The Venn diagram showed that ultrasound confirmed the prolapse diagnosis in only 4 symptomatic women in whom prolapse was not detected at POP-Q examination, whereas POP-Q was diagnostic for 16 women for whom prolapse was missed on ultrasound diagnosis. Some previous studies have found that clinical and ultrasound assessment both correlate with prolapse symptoms, whereas others have found that ultrasound has an inferior performance compared with clinical examination [18,19,20].

Twenty percent of women with bulge symptoms in the present study had no significant prolapse on ultrasound or POP-Q examination. We have no information that explains why these women had a sensation of a vaginal bulge. Pelvic floor muscle training can reduce symptoms in women with small prolapses [21], and weaker pelvic floor muscle contraction is a possible explanation for discordance between symptoms and anatomy. Another explanation is that some study participants were not able to perform a proper Valsalva without levator co-activation, which could have masked a clinically relevant prolapse in this examination setting.

Other symptoms were more weakly correlated with POP-Q and ultrasound measurements. “Splinting” was associated with descent on POP-Q, and “pushing to empty urinary bladder” was associated with bladder descent on ultrasound. This indicates that difficulties with bladder and bowel emptying also depend on factors other than the degree of prolapse, supported by findings in previous studies [8, 22]. Constipation and bowel motility disturbances are common causes of bowel emptying difficulties, and a spastic pelvic floor could be another explanation [23]. Therefore, surgical treatment of prolapse in patients with emptying difficulties does not necessarily lead to symptom relief [24]. Other causes of bladder and bowel symptoms should be investigated before considering prolapse surgery, especially in the absence of a significant anatomical prolapse [8, 22]. As this study was performed on women from a normal population, other symptoms may have a stronger association with POP-Q or ultrasound measurements in patient populations.

For the posterior compartment, ultrasound has the potential to reveal information about rectal intussusception, internal herniation, and enterocele, which could be important in the evaluation and planning of treatment for women with prolapse [14, 25]. As ultrasound is available in most gynecological departments, this should be performed for women with bowel-emptying difficulties and no prolapse on POP-Q before referring to other imaging modalities. Ultrasound can also be used to diagnose levator ani muscle trauma. This is important when choosing treatment and informing patients, as women with major levator trauma are at an increased risk for expulsion of a ring pessary and of prolapse recurrence after surgery [26, 27].

One strength of this study is the large number of women recruited from a normal population. We could therefore demonstrate a similar and even stronger association among POP-Q, ultrasound, and prolapse symptoms than previous studies in patient populations [12, 18]. We used a Norwegian translation of a validated questionnaire about symptoms of pelvic floor disorders. Standardized criteria were used to define pelvic organ prolapse on clinical examination (POP-Q) and ultrasound.

One possible weakness is that symptomatic women may be easier to recruit, and the prevalence of prolapse could be higher than in the normal population from which these women were recruited. The prolapse prevalence was similar with previous studies on similar populations reporting POP-Q ≥ 2 in 35–63% of women [6, 28]. Another weakness is the cross-sectional study design, with no possibility of following the development of anatomical prolapse and symptoms over time. A previous study found that posterior vaginal prolapse did not increase the odds that defecatory symptoms would occur among asymptomatic women, but for women with established posterior vaginal prolapse, defecatory symptoms were associated with more rapid worsening of anatomical prolapse over time [29]. A follow-up of our study population after 10–15 years could add information about changes in anatomical prolapse and symptoms over time. Many women in this population had prolapse in more than one compartment. Studying women with single-compartment prolapse could have given different results [30]. Median values of descent were statistically significantly different in symptomatic and asymptomatic women, but the range values overlapped. This implies that POP-Q and ultrasound cannot be used to distinguish between women with and without symptoms and also supports the notion that only women with a symptomatic prolapse need treatment.

In conclusion, the correlation and agreement between POP-Q and ultrasound measurement of prolapse were moderate to strong in the anterior and middle compartments and weak in the posterior compartment in women from a normal population. Both methods were strongly associated with the symptom “seeing or feeling a vaginal bulge,” and POP-Q diagnosis of prolapse was more strongly associated with this symptom than ultrasound. Therefore, ultrasound cannot substitute POP-Q examination in the diagnosis of pelvic organ prolapse. Still, ultrasound can be used as a helpful complement providing additional information about enterocele, rectal intussusception, and muscle trauma, which is relevant for the choice of treatment and information for women with pelvic organ prolapse.

References

Lowenstein E, Ottesen B, Gimbel H. Incidence and lifetime risk of pelvic organ prolapse surgery in Denmark from 1977 to 2009. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26(1):49–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-014-2413-y.

Jelovsek JE, Maher C, Barber MD. Pelvic organ prolapse. Lancet. 2007;369(9566):1027–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60462-0.

Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K, Brubaker LP, DeLancey JO, Klarskov P, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175(1):10–7.

Tan JS, Lukacz ES, Menefee SA, Powell CR, Nager CW, San Diego Pelvic Floor C. Predictive value of prolapse symptoms: a large database study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16(3):203–9; discussion 209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-004-1243-8.

Swift SE, Tate SB, Nicholas J. Correlation of symptoms with degree of pelvic organ support in a general population of women: what is pelvic organ prolapse? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(2):372–7. discussion 377–9

Swift S, Woodman P, O'Boyle A, Kahn M, Valley M, Bland D, et al. Pelvic Organ Support Study (POSST): the distribution, clinical definition, and epidemiologic condition of pelvic organ support defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(3):795–806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2004.10.602.

Ellerkmann RM, Cundiff GW, Melick CF, Nihira MA, Leffler K, Bent AE. Correlation of symptoms with location and severity of pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185(6):1332–7; discussion 1337-1338. https://doi.org/10.1067/mob.2001.119078.

Bradley CS, Nygaard IE. Vaginal wall descensus and pelvic floor symptoms in older women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(4):759–66. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000180183.03897.72.

El Sayed RF, Alt CD, Maccioni F, Meissnitzer M, Masselli G, Manganaro L, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of pelvic floor dysfunction—joint recommendations of the ESUR and ESGAR Pelvic Floor Working Group. Eur Radiol. 2016;27(5):2067–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-016-4471-7.

Dietz HP, Lekskulchai O. Ultrasound assessment of pelvic organ prolapse: the relationship between prolapse severity and symptoms. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;29(6):688–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.4024.

Barber MD, Walters MD, Bump RC. Short forms of two condition-specific quality-of-life questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders (PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(1):103–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.025.

Dietz HP, Kamisan Atan I, Salita A. Association between ICS POP-Q coordinates and translabial ultrasound findings: implications for definition of 'normal pelvic organ support'. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47(3):363–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.14872.

Shek KL, Dietz HP. What is abnormal uterine descent on translabial ultrasound? Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26(12):1783–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-015-2792-8.

Dietz HP, Steensma AB. Posterior compartment prolapse on two-dimensional and three-dimensional pelvic floor ultrasound: the distinction between true rectocele, perineal hypermobility and enterocele. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;26(1):73–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.1930.

Rodrigo N, Shek KL, Dietz HP. Rectal intussusception is associated with abnormal levator ani muscle structure and morphometry. Tech Coloproctol. 2011;15(1):39–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-010-0657-1.

Volloyhaug I, Morkved S, Salvesen O, Salvesen KA. Forceps delivery is associated with increased risk of pelvic organ prolapse and muscle trauma: a cross-sectional study 16-24 years after first delivery. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46(4):487–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.14891.

Volloyhaug I, Morkved S, Salvesen O, Salvesen K. Pelvic organ prolapse and incontinence 15–23 years after first delivery: a cross-sectional study. BJOG. 2015;122(7):964–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13322.

Broekhuis SR, Kluivers KB, Hendriks JC, Futterer JJ, Barentsz JO, Vierhout ME. POP-Q, dynamic MR imaging, and perineal ultrasonography: do they agree in the quantification of female pelvic organ prolapse? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(5):541–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-009-0821-1.

Lone FW, Thakar R, Sultan AH, Stankiewicz A. Accuracy of assessing Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification points using dynamic 2D transperineal ultrasound in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23(11):1555–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-012-1779-y.

Kluivers KB, Hendriks JC, Shek C, Dietz HP. Pelvic organ prolapse symptoms in relation to POPQ, ordinal stages and ultrasound prolapse assessment. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(9):1299–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-008-0634-7.

Panman C, Wiegersma M, Kollen BJ, Berger MY, Lisman-Van Leeuwen Y, Vermeulen KM, et al. Two-year effects and cost-effectiveness of pelvic floor muscle training in mild pelvic organ prolapse: a randomised controlled trial in primary care. BJOG. 2017;124(3):511–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13992.

Grimes CL, Lukacz ES. Posterior vaginal compartment prolapse and defecatory dysfunction: are they related? Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23(5):537–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-011-1629-3.

Beer-Gabel M, Carter D. Comparison of dynamic transperineal ultrasound and defecography for the evaluation of pelvic floor disorders. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30(6):835–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-015-2195-9.

Guzman Rojas R, Kamisan Atan I, Shek KL, Dietz HP. Defect-specific rectocele repair: medium-term anatomical, functional and subjective outcomes. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;55(5):487–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.12347.

Guzman Rojas R, Kamisan Atan I, Shek KL, Dietz HP. The prevalence of abnormal posterior compartment anatomy and its association with obstructed defecation symptoms in urogynecological patients. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(6):939–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-015-2914-3.

Cheung RY, Lee JH, Lee LL, Chung TK, Chan SS. Levator ani muscle avulsion is a risk factor for vaginal pessary expulsion within 1 year for pelvic organ prolapse. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;50(6):776–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.17407.

Model AN, Shek KL, Dietz HP. Levator defects are associated with prolapse after pelvic floor surgery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;153(2):220–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.07.046.

Nygaard I, Bradley C, Brandt D; Women's Health Initiative. Pelvic organ prolapse in older women: prevalence and risk factors. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(3):489–97. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000136100.10818.d8.

Handa VL, Munoz A, Blomquist JL. Temporal relationship between posterior vaginal prolapse and defecatory symptoms. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;216(4):390.e1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2016.10.021.

Blain G, Dietz HP. Symptoms of female pelvic organ prolapse: correlation with organ descent in women with single compartment prolapse. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;48(3):317–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-828X.2008.00872.x.

Acknowledgements

We thank Christine Østerlie and Tuva K. Halle for help with identifying potential study participants and Guri Kolberg for help with the coordination of clinical examinations.

Funding

The study was financially supported by the Norwegian Women’s Public Health Association/the Norwegian Extra Foundation for Health and Rehabilitation through Extra funds, Trondheim University Hospital, Norway, and by Desarrollo médico, Clínica Alemana de Santiago. The funders played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; or in the writing of the report and decision to submit the article for publication. All researchers were independent from the funders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PPTX 41 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Volløyhaug, I., Rojas, R.G., Mørkved, S. et al. Comparison of transperineal ultrasound with POP-Q for assessing symptoms of prolapse. Int Urogynecol J 30, 595–602 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-018-3722-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-018-3722-3