Abstract

The objective of this study was to identify factors associated with anal sphincter laceration in primiparous women. A subpopulation of 40,923 primiparous women at term with complete data sets was abstracted from a state-wide perinatal database in Germany. Outcome variable was anal sphincter laceration. Independent variables were 17 known obstetrical risk factors/conditions/interventions impacting childbirth recorded on the perinatal data collection sheet. Cross table analysis followed by logistic regression analysis was used for data analysis. Logistic regression showed episiotomy (OR, 3.23; CI, 2.73–3.80) and forceps delivery (OR, 2.68, CI, 2.17–3.33) to be most strongly associated with anal sphincter laceration. Women with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, and smokers had a significantly lower risk of anal sphincter laceration. Local, pudendal, and epidural analgesia all reduced the risk of anal sphincter laceration. Iatrogenic factors most strongly associated with anal sphincter laceration in primiparous women include routine episiotomy and forceps delivery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 2001, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations introduced anal sphincter lacerations as a quality indicator of obstetrical care and, as of 2003, started publicizing this information for accredited hospitals [1]. The rationale is that these lacerations can result in significant long-term morbidity including, but not limited to, dyspareunia, flatal and fecal incontinence, anorectal abscess, and rectovaginal fistula [1, 2]. As active measures to “protect” the perineum, e.g., perineal massage, have been and continue to be investigated without any of them showing a clear-cut benefit [3–5], the commissions advisory panel apparently intended to promote the prudent application of obstetrical interventions that are know to be associated with anal sphincter laceration, e.g., routine episiotomy or forceps delivery [6–8]. Among extensive existing literature, there are only few studies that have large enough numbers to permit a comprehensive analysis of the contemporary process of parturition [7, 9, 10].

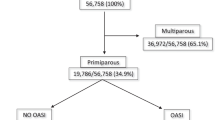

Drawing on a large state-wide perinatal database spanning the years from 1991–1997 including 40,923 complete data sets, we set out juxtaposing maternal factors, fetal factors, and contemporary obstetrical interventions and anal sphincter laceration to determine if and to what extent those factors may contribute to this condition.

Materials and methods

We used a version of the perinatal database of the State of Schleswig–Holstein, Germany between 1991 and 1997 containing data that had been blinded in compliance with national and state health data protection regulations. This study has been reviewed by Wayne State University’s Human Investigation Committee and found to qualify for exemption according to paragraph #2 of 45 CFR 46.101 (b) of the Code of Federal Regulations of the Department of Health and Human Services. Data used in this paper had been collected prospectively at the time of admission for delivery. Upon taking the mother’s “history and physical” data already entered in a prenatal care booklet, it was reviewed with the mother. This data pertained to past health issues, those existing at the beginning of and those having arisen during pregnancy. This information was then transferred to a data collection form divided into five sections: maternal socio-demographic characteristics, course of pregnancy including risk factors, delivery characteristics including indications for operative delivery, characteristics of the neonate, and postpartum maternal complications. The data collection sheet did not provide for entry of different types of episiotomy. On a monthly basis, each delivery unit in the state of Schleswig–Holstein forwards the perinatal data sheets to a central collecting agency, where the data is entered into a computer and checked for plausibility.

Inclusion criteria for our study were nulliparity, singleton pregnancy, 37–42 completed weeks gestation, vertex presentation, and vaginal delivery of a live or still born baby.

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 13.0 using cross table analysis with χ 2-testing to determine differences in rates between anal sphincter laceration and presence or absence of obstetrical risk factors/conditions/interventions impacting child birth defined in the perinatal data collection sheet. Those shown to be associated with anal sphincter laceration were included in logistic regression analysis to determine whether they were independently associated with anal sphincter laceration. A sample size estimate revealed that 18,779 complete data sets were needed to demonstrate an association between variables and anal sphincter laceration with a p < 0.001 and a power of 99% [11]. Bonferroni’s correction was used with exact two-sided p < 0.005 (p = 0.05/17) based on 17 variables considered significant to alert for any variables in the logistic regression that may indicate mere chance than true association with anal sphincter association. For practical obstetrical purposes, continuous variables were transformed into interval variables such as to allow for analysis of interval scales. For practical, statistical reasons up to a maximum of seven intervals rather than percentiles were chosen: duration of labor, seven increments of 2 h starting at <2 h, ending at ≥12 h; active pushing as of the woman’s urge to push, seven increments of 5 min starting at <5 min, ending at ≥30 min; birth weight, seven increments of 250 g starting at <2,500 g, ending at ≥4,000 g; head circumference, seven increments of 1 cm starting at <32 cm, ending at ≥38 cm. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the weight recorded at the last prenatal visit before delivery; women were classified into BMI <25, 25–29.9, 30–34.9, 35–39.9, and ≥40. For variables with several classes (maternal BMI, birth weight, head circumference, duration of labor, duration of pushing, and analgesia), in logistic regression analysis, the class consisting of the highest number of women was chosen as the reference class. Outcome variable was absence or presence of anal sphincter laceration. Independent dichotomous variables were: advanced maternal age (AMA, age < or ≥35 years), cigarette smoking, prolonged first (>6 h) and second (>2 h) stage of labor, episiotomy, vertex malpresentation, e.g., occiput posterior, operative vaginal delivery separately for forceps and vacuum, labor augmentation with oxytocin, and administration of i.v. tocolytics (fenoterol; i.v. push or, e.g., after a prolonged deceleration as long as needed to have a fetal heart rate between 120 and 160 bpm for 30 min).

Results

From 170,258 singleton pregnancies, 40,923 complete data sets of women meeting inclusion criteria were used. The study population was exclusively of Caucasian origin. Table 1 displays descriptive statistics as well as results of cross table analysis and logistic regression of obstetrical risk factors/conditions/interventions impacting child birth in women without and with anal sphincter laceration.

Women with anal sphincter laceration were slightly older than those without the affliction (28.4 ± 4.0 vs 27.1 ± 4.5 years, mean ± standard deviation; p < 0.001). Moreover, women with anal sphincter laceration had longer been in labor (9.0 ± 5.7 h vs 8.1 ± 5.3 h; p < 0.001), had longer been actively pushing (22 ± 15 min vs 19 ± 14 min; p < 0.001), and their off-spring had higher birth weights (3,600 ± 430 g vs 3,455 ± 430 g; p < 0.001) and greater head circumferences (35.4 ± 1.5 cm vs 34.9 ± 1.4 cm; p < 0.001) than controls.

Bivariate (cross table) analysis revealed significantly higher proportions of age ≥35 years, i.v. tocolysis, prolonged second stage of labor, oxytocin augmentation, episiotomy, forceps, vacuum, and abnormal vertex presentation in women who suffered from anal sphincter laceration than in those who did not (Table 1).

In contrast, women who smoked cigarettes and women with a BMI > 30 kg/m2 had lower rates of anal sphincter laceration (Table 1).

The following 17 variables were forcedly entered into logistic regression: age ≥ 35 years, BMI, smoker, oxytocin augmentation, i.v. tocolysis, analgesia, abnormal vertex presentation, prolonged first stage, prolonged second stage, duration of labor, duration of pushing, pyrexia in labor, episiotomy, forceps, vacuum, birth weight, and head circumference. Among these, the following were significantly associated with anal sphincter laceration: episiotomy (OR, 3.23; CI 2.73–3.80), forceps delivery (OR, 2.68; CI, 2.17–3.32), abnormal vertex presentation (OR, 1.71; CI, 1.43–2.04), use of fenoterol (OR, 1.33; CI, 1.15–1.54), and vacuum delivery (OR, 1.21; 1.03–1.42; Table 1). Whereas anal sphincter lacerations were observed in any birth weight or head circumference category, as compared with the reference groups 3,250–3,499 g and 35–35.9 cm, a significant and steady increase in laceration rates started to be seen at birth weights greater than 3,750 g [3,750–3,999 g (OR, 1.21; CI, 1.04–1.41) and ≥4,000 g (OR, 1.53; CI, 1.29–1.80); Fig. 1] and head circumferences of 36 cm and greater [36–36.9 cm (OR, 1.21; CI, 1.06–1.37), 37–37.9 cm (OR, 1.23; CI, 1.04–1.46), and ≥38 cm (OR, 1.55; CI, 1.22–1.96); Fig. 2]. Duration of pushing, but not duration of labor, was significantly associated with anal sphincter lacerations after more than 25 min [25–29.9 min (OR, 1.29; CI, 1.04–1.60) and ≥30 min (OR, 1.32; CI, 1.11–1.48)] in this model (Figs. 3 and 4). Whereas oxytocin labor augmentation was not associated with anal sphincter lacerations, fenoterol administration increased the risk by 33% (OR, 1.33; CI, 1.15–1.54; Table 1).

Rates of anal sphincter laceration in different birth weight classes in 40,293 primiparous women. Numbers, number of cases in class; asterisks, statistically significantly different (p < 0.001) from reference class (column in gray) as determined by logistic regression analysis. Odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals: <2,750 g (OR, 0.580 and CI, 0.42–0.80), 2750–2,999 g (OR, 0.64; CI, 0.51–0.80), 3,000–3,249 g (OR, 0.80 and CI, 0.68–0.93), 3,500–3,749 g (OR, 1.12 and CI, 0.98–1.29), 3,750–3,999 g (OR, 1.21; CI, 1.04–1.41), and ≥4,000 g (OR, 1.53 and CI, 1.29–1.80)

Rates of anal sphincter laceration in different head circumference classes of newborns in 40,293 primiparous women. For legend, see Fig. 1. Odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals: <33 cm (OR, 0.73 and CI, 0.53–1.01), 33–33.9 cm (OR, 0.89 and CI, 0.73–1.08), 34–34.9 cm (OR, 0.98 and CI, 0.86–1.13), 36–36.9 cm (OR, 1.21 and CI, 1.06–1.37), 37–37.9 cm (OR, 1.23 and CI, 1.04–1.46), and ≥38 cm (OR, 1.55 and CI, 1.22–1.96)

Rates of anal sphincter laceration in different duration-of-labor classes in 40,293 primiparous women. For legend, see Fig. 1. Odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals. <2 h (OR, 0.74 and CI, 0.44–1.25), 2–3.9 h (OR, 1.07 and CI, 0.89–1.27), 4–5.9 h (OR, 0.93 and CI, 0.80–1.07), 8–9.9 h (OR, 1.0 and CI, 0.86–1.16), 10–11.9 h (OR, 1.14 and CI, 0.96–1.34), and ≥12 h (OR, 1.14 and CI, 0.98–1.31)

Rates of anal sphincter laceration in different duration-of-active-pushing classes in 40,293 primiparous women. For legend, see Fig. 1. Odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals. <5 min (OR, 0.88 and CI, 0.64–1.20), 5–9.9 min (OR, 0.97 and CI, 0.83–1.14), 10–14.9 min (OR, 1.02 and CI, 0.89–1.18), 20–24.9 min (OR, 1.15 and CI, 0.99–1.38), 25–29.9 min (OR, 1.29 and CI, 1.04–1.60), and ≥30 min (OR, 1.32 and CI, 1.15–1.52)

Compared to “no analgesia”, local, pudendal, or epidural analgesia all reduced the risk of anal sphincter laceration (Table 1). Interestingly, women who smoked and those with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 had a significantly lower risk of anal sphincter laceration (Fig. 5).

Rates of anal sphincter laceration in different BMI classes in 40,293 primiparous women. For legend, see Fig. 1. Odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals: <25 (OR, 1.15 and CI, 1.02–1.30), 30–34.9 (OR, 0.88 and CI, 0.78–0.98), 35–39.9 (OR, 0.55 and CI, 0.43–0.71), and ≥40 (OR, 0.63 and CI, 0.42–0.95)

Discussion

During the time period of our study, obstetrics in this most northern part of Germany bordering the Scandinavian countries was characterized by almost every other woman’s labor being augmented with oxytocin, almost 10% receiving iv. fenoterol for intrauterine fetal resuscitation or for epidural placement, a comparably low rate (19%) of women receiving epidural anesthesia for pain relief, and an episiotomy rate of almost 80%. In terms of operative vaginal deliveries, obstetricians by far preferred vacuum to forceps. Given this scenario, the rate of anal sphincter lacerations was 5.2%; recent studies from Austria and the USA quote rates of 4.4 and 4.6%, respectively [6, 12]. Our analysis shows that obstetrical interventions as well as fetal and maternal factors were associated with anal sphincter lacerations. Interestingly, obstetrical interventions, predominantly episiotomy, and forceps assisted delivery had the gravest impact.

Historically, caretakers focused on avoiding anal sphincter laceration by manually supporting the perineum of head and shoulders during delivery, many times unsuccessfully [5]. One of the protagonists of perineotomy who, making necessity a virtue, tried to avoid more severe injury by intentionally creating space by means of episiotomy/perineotomy was Michaelis in Germany in 1799. In fact, he performed a midline perineotomy in a selected case; subsequently, systematic studies from the US as well as from Europe reporting favorably on this technique appeared in the literature [13–15] Indiscriminate use of episiotomy led to the currently prevailing notion that “routine” episiotomy does more harm than good [16]. Our database supports that notion with the caveat that we do not have information on the type of incision. During the study period, midline as well as mediolateral episiotomies were used, the former said to promote, whereas the latter said to protect from perineal injury [6, 9, 12, 15, 17]. Although the direction of the episiotomy seems to be important, other factors are likely to be as important, e.g., cutting the episiotomy at or shortly after the pain acme, with one expeditious cut at exactly the anticipated length or controlling expulsion of head and shoulders [8, 18].

Use of forceps in our model is the second most prominent factor in the strength of association with anal sphincter injury. This is in line with the literature where there is now unequivocal agreement that forceps-assisted vaginal delivery exposes surrounding tissues and the pelvic floor at risk for potentially severe damage [6, 7, 9, 19]. In contrast, vacuum assisted delivery in our study shows a much weaker association with anal sphincter injury than forceps-assisted delivery.

Among the remaining factors in our study shown to be associated with anal sphincter injury, “abnormal fetal vertex presentation,” e.g., occiput posterior or occiput transverse, fetal weight, head circumference, and prolonged labor have been recognized as risk factors for anal sphincter laceration in previous publications [6–9, 12, 19–22]. An additional factor in our study presenting a risk for anal sphincter lacerations was prolonged pushing, starting with the parturients urge to push of more than 25 min [18, 23]. Augmentation of labor with i.v. oxytocin is probably the most frequent medical intervention during labor. Our findings are in accord with those of others who, also, did not find oxytocin augmentation to be an independent factor associated with pelvic floor injury [24]. We did, however, find another medical intervention, i.v. administration of fenoterol, to pose an independent risk of anal sphincter laceration to the almost 10% of women in our study who received this β-sympathomimetic agent for intrauterine fetal resuscitation or to block contractions while an epidural catheter was placed. To our knowledge, the role of β-sympathomimetics has never been examined in any study of pelvic floor injuries. Beta-sympathomimetics have profound pharmacological effects including, but not limited to, increased tissue oxygen consumption, hyperglycemia, hypokalemia, and an increase in lactic acid output [25, 26]; they may alter the electro-mechanical coupling mechanism of muscle cells via calcium antagonism, which altogether potentially promotes tissue disintegration under physical stress [27, 28].

Still another “drug” that, in contrast to fenoterol, we found to have a “protective” effect on anal sphincter laceration, is nicotine, i.e., cigarette smoking. Whereas many authors reported their rates of smokers in subjects and controls, we are not aware of any who included smoking as a potentially independent predictor for anal sphincter laceration. Nicotine has common elements with the neurotransmitter acetylcholine; it can penetrate lipophilic membranes including the blood–brain barrier and the blood–placental barrier. It has been shown to elicit a wide variety of complex stimulant and depressant effects that involve the central and peripheral nervous, cardiovascular, endocrine, gastrointestinal, and skeletal motor systems [29]. Most importantly, nicotine stimulates Renshaw inhibitory neurons in the spinal cord, which leads to a skeletal muscle relaxant effect [30].

We recently reported that the success rate of vaginal births after cesarean is inversely associated with maternal BMI [31]. Our current data supported by those of others show that in primiparous women with vaginal birth, a higher BMI is associated with a lower rate of perineal injury [22]. On the other hand, a positive correlation between BMI and length of laceration has been reported [19, 32].

In agreement with the findings of the Collaborative Perinatal Project 1959–1965 in the USA in primiparous women, we did not find advanced maternal age being associated with perineal injuries [16].

Epidural analgesia, inaugurated by Fidel Pages in 1921 and increasingly used in obstetrics since the 1980s, has come more and more under scrutiny for its role in anal sphincter laceration, specifically for allegedly increasing duration of second stage labor and increasing risk of operative delivery; it has also been linked to an increased C/S rate and increased fetal malposition [24, 33–37]. Indeed, our cross table analysis seemed to confirm those allegations; however, when subjected to multiple logistic regression analysis and when controlled for by other forms of analgesia, we actually found a beneficial effect on anal sphincter laceration.

In conclusion, in our model, episiotomy and forceps-assisted delivery remained the strongest factors associated with anal sphincter lacerations in primiparous women at term. Numerous other factors displayed much smaller, although significant, associations with anal sphincter laceration.

References

Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) http://www.jointcommission.org/NR/rdonlyres/F438F258-BDEE-4A11-A632-27FC193C73CE/0/2zr_PR3.pdf

Fenner DE, Genberg B, Brahma P, Marek L, DeLancey JO (2003) Fecal and urinary incontinence after vaginal delivery with anal sphincter disruption in an obstetrics unit in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol 189:1543–1549 (discussion 1549–1550)

Beckmann MM, Garrett AJ (2006) Antenatal perineal massage for reducing perineal trauma. Birth 33:159

Eogan M, Daly L, O’Herlihy C (2006) The effect of regular antenatal perineal massage on postnatal pain and anal sphincter injury: a prospective observational study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 19:225–229

Goodell W (1871) A critical inquiry into the management of the perineum during labor. Am J Med Sci 61:53

Christianson LM, Bovbjerg VE, McDavitt EC, Hullfish KL (2003) Risk factors for perineal injury during delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 189:255–260

Dandolu V, Chatwani A, Harmanli O, Floro C, Gaughan JP, Hernandez E (2005) Risk factors for obstetrical anal sphincter lacerations. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 16(4):304–307

Handa VL, Harris TA, Ostergard DR (1996) Protecting the pelvic floor: obstetric management to prevent incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol 88:470–478

de Leeuw JW, Struijk PC, Vierhout ME, Wallenburg HC (2001) Risk factors for third degree perineal ruptures during delivery. BJOG 108:383–387

Handa VL, Danielsen BH, Gilbert WM (2001) Obstetric anal sphincter lacerations. Obstet Gynecol 98:225–230

Hsieh FY (1989) Sample size tables for logistic regression. Stat Med

Hudelist G, Gelle’n J, Singer C, Ruecklinger E, Czerwenka K, Kandolf O, Keckstein J (2005) Factors predicting severe perineal trauma during childbirth: role of forceps delivery routinely combined with mediolateral episiotomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 192:875–881

Broomall A (1878) The operation of episiotomy as a prevention of perineal ruptures during labor. Am J Obstet 11:517–527

Credé uC (1884) Ueber die Zweckmässigkeit der einseitigen seitlichen Incision beim Dammschutzverfahren. Archiv für Gynäkologie 24(150):148–168

Thacker SB, Banta HD (1983) Benefits and risks of episiotomy: an interpretative review of the English language literature, 1860–1980. Obstet Gynecol Surv 38:322–338

Shiono P, Klebanoff MA, Carey JC (1990) Midline episiotomies: more harm than good? Obstet Gynecol 75:765–770

Coats PM, Chan KK, Wilkins M, Beard RJ (1980) A comparison between midline and mediolateral episiotomies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 87:408–412

Samuelsson E, Ladfors L, Wennerholm UB, Gareberg B, Nyberg K, Hagberg H (2000) Anal sphincter tears: prospective study of obstetric risk factors. BJOG 107:926–931

Burrows LJ CG, Leffler KS, Witter FR (2004) Predictors of third and fourth-degree perineal lacerations. J Pelvic Med Surg 10:15–17

Cheng YW, Hopkins LM, Caughey AB (2004) How long is too long: Does a prolonged second stage of labor in nulliparous women affect maternal and neonatal outcomes? Am J Obstet Gynecol 191:933–938

Fitzpatrick M, Harkin R, McQuillan K, O’Brien C, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C (2002) A randomised clinical trial comparing the effects of delayed versus immediate pushing with epidural analgesia on mode of delivery and faecal continence. BJOG 109:1359–1365

Klein MC, Janssen PA, MacWilliam L, Kaczorowski J, Johnson B (1997) Determinants of vaginal-perineal integrity and pelvic floor functioning in childbirth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 176:403–410

Hansen SL, Clark SL, Foster JC (2002) Active pushing versus passive fetal descent in the second stage of labor: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 99:29–34

Robinson JN, Norwitz ER, Cohen AP, McElrath TF, Lieberman ES (1999) Epidural analgesia and third- or fourth-degree lacerations in nulliparas. Obstet Gynecol 94:259–262

Anotayanonth S, Subhedar NV, Garner P, Neilson JP, Harigopal S (2004) Betamimetics for inhibiting preterm labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD004352

Wischnik A, Mendler N, Schroll A, Heimisch W, Weidenbach A (1982) [The cardiac hazard of tocolysis and antagonizing possibilities. II. Communication: protection of the myocardium by means of substitution of magnesium]. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 42:537–542

Mosler KH (1975) The treatment of threatened premature labor by tocolytics, Ca++-antagonists and anti-inflammatory drugs. Arzneimittelforschung 25:263–266

Wischnik A, Mendler N, Heimisch W, Schroll A, Weidenbach A (1982) [The cardiac hazard of tocolysis and antagonising possibilities. I. The haemodynamic situation of the patient during tocolysis/Protection of the myocardium by means of cardioselective beta-blockade. Experimental results]. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 42:286–290 (author’s transl)

Domino EF (1986) Nicotine: a unique psychoactive drug-arousal with skeletal muscle relaxation. Psychopharmacol Bull 22:870–874

Domino EF, Kadoya C, Matsuoka S (1994) Recovery cycle of the Hoffmann reflex of tobacco smokers and nonsmokers: relationship to plasma nicotine and cotinine levels. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 46:527–532

Bujold E, Hammoud A, Schild C, Krapp M, Baumann P (2005) The role of maternal body mass index in outcomes of vaginal births after cesarean. Am J Obstet Gynecol 193:1517–1521

Nager CW, Helliwell JP (2001) Episiotomy increases perineal laceration length in primiparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 185:444–450

Carroll TG, Engelken M, Mosier MC, Nazir N (2003) Epidural analgesia and severe perineal laceration in a community-based obstetric practice. J Am Board Fam Pract 16:1–6

de Lange JJ, Cuesta MA, Cuesta de Pedro A (1994) Fidel pages mirave (1886–1923). The pioneer of lumbar epidural anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 49:429–431

Tan TK (1998) Epidural analgesia in obstetrics. Ann Acad Med Singap 27:235–242

Ural SH, Roshanfekr D, Witter FR (2000) Fourth-degree lacerations and epidural anesthesia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 71:231–233

Walker MP, Farine D, Rolbin SH, Ritchie JW (1991) Epidural anesthesia, episiotomy, and obstetric laceration. Obstet Gynecol 77:668–671

Acknowledgment

This study was conducted at Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan.

There was no funding associated with this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Baumann, P., Hammoud, A.O., McNeeley, S.G. et al. Factors associated with anal sphincter laceration in 40,923 primiparous women. Int Urogynecol J 18, 985–990 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-006-0274-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-006-0274-8