Abstract

This paper examines the response of household debt to households’ perception of house prices using data from the first wave of the Household Finance and Consumption Survey. Whereas the literature has hitherto emphasized the effects of housing wealth on consumption, this study concentrates on the effects on debt accumulation—distinguishing mortgage debt from non-mortgage debt and inspecting over-indebtedness. Different measures of housing wealth are considered, controlling for tenure years. The findings reveal that the effects of housing wealth differ by type of loans and with the measure of housing wealth. Over-indebtedness is driven by the same factors that determine mortgage debt, suggesting a strong association between having outstanding liabilities from the primary residence and the risk of entering into default. Further estimations by different income and wealth classes revealed dissimilar housing wealth effects, with non-mortgage debt tending to rise among lower-income households and over-indebtedness tending to be larger among the wealthier.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Until the 2007–2008 global economic crisis, advanced economies went through a period of increased liquidity and historically low interest rates in which household debt accumulated faster than the GDP growth rate. Alongside that, while house prices kept rising steadily to reach alarming levels in several countries, new mortgage contracts on offer made housing ownership less prohibitive, thus inflating the share of homeowners among the total population. In the aftermath of the crisis, indebted households felt under pressure to sell their residential properties at low market values, often incurring losses to avoid defaulting. This contributed to a climate of instability for which households’ former financial choices were heavily blamed.

There has been a surge in studies on the macroeconomic impacts of housing and the housing market (e.g. Kivedal 2014; Kuang 2014; Christensen et al. 2016; Rubio and Carrasco-Gallego 2016; Guerrieri and Iacoviello 2017; Lambertini et al. 2017), motivated by the acknowledgement that within advanced economies, housing wealth accounts for about half of households’ wealth and that it tended to move together with aggregate consumption after the II World War (Iacoviello 2005). In the class of DSGE models, housing is included among households’ preferences, while both the effects of credit shocks on households’ decisions and the association between rising expectations of house prices and their actual increase are checked. The expansion of housing wealth as a result of increases in housing prices is shown to smooth collateral constraints and to fuel debt-driven consumption.

By placing households’ choices at the heart of the mechanism that explains the business cycle, these models have ascertained the need to test their results with microdata. Concurrently, empirical studies have corroborated that changes in housing prices impact households’ consumption, investment, and borrowing decisions (Case et al. 2005; Mian et al. 2013) and their financial behaviour in general (Campbell 2006). When homeowners recognize the appreciation of housing prices as a permanent capital gain, they adjust their consumption levels in response to both the positive effect on their lifetime wealth and the decline of the value of their outstanding liabilities which are mostly with a mortgage. Moreover, homeowners’ borrowing constraints are relaxed once housing prices increase, and consumption is then stimulated (Campbell and Cocco 2007; Mian and Sufi 2014). In this framework, and given that the residential property is a non-liquid asset, with the prospect of appreciating housing prices, households may feel the urge to contract new loans to smooth consumption, adjusting their current expenditure to their new perceived wealth. In fact, to understand the drivers of household indebtedness it is crucial to take into account the role played by the household perception of housing prices in their decision to demand new credit.

This paper studies the effects of a change in housing wealth, as reported by its homeowner and in comparison with its acquisition cost, on the average amounts of debt held by Portuguese households. The study relies on microdata retrieved from the Household Finance and Consumption Survey (Household Finance and Consumption Network 2013) and focuses on the impact of an increase in housing valuation on household debt accumulation, discriminating total debt, mortgage debt, and non-mortgage debt. Also, since the residential property represents at once the largest fraction of the typical homeowner’s debt as the major share of their wealth, it seems natural to also inspect how wealth perception from housing prices encourages accumulating debt up to risky levels. To this end, additional estimations capture housing wealth effects on over-indebtedness relying on a measure of risk that combines three standard thresholds of risky debt.

This paper is different from the existing literature in four aspects. First, by assessing housing wealth through household appraisal of house prices, it distinguishes the absolute appreciation of housing from its average annual appreciation. Economic psychology has emphasized how biased perceptions mould a household’s financial decisions and hence should be considered when studying households’ behaviours. The second aspect is the examination of the effects of housing wealth on debt rather than on consumption. Whenever the housing markets signal an upsurge, liquidity-constrained homeowners face an opportunity to access other consumption goods through debt. Third, by studying over-indebtedness, an issue often neglected in the literature; a household holding high outstanding liabilities is most likely a homeowner who borrowed to buy the residential property and uses their dwelling as a warranty. The fourth aspect is the refining of the analysis to take into account households’ distribution by income and wealth, and performing estimations to perceive whether there are significant differences in a household’s response to housing wealth across these distributions.

Our findings indicate that when deciding how much debt to accumulate, households do respond to housing wealth but with opposite sensibilities and different magnitudes given the measure of housing wealth. These suggest that the type of perception on housing wealth is relevant when capturing its effect on debt. Moreover, households were shown to display opposite behaviours in their choice of mortgage debt and non-mortgage debt, meaning that their decisions take into account which type of counterpart they get in exchange for their liabilities—that is, whether a consumption good is a reliable asset as well, or just a consumption good. Lastly, results by income and wealth indicated that lower-income households were more prone to use housing as collateral, with wealthier households displaying relatively higher over-indebtedness ratios in response to housing wealth.

The paper unfolds as follows. The next section looks at the most relevant literature on this subject. Section 3 presents the model variables and the data and methodology. Section 4 presents and discusses the results of estimations. Section 5 concludes.

2 Literature review

Within traditional economic theory, debt is a side effect of households’ consumption decisions, as in Modigliani and Brumberg (1954)’s life-cycle model and in Friedman (1957)’s permanent income hypothesis. Forward-looking consumers acting in complete markets choose an even pattern of current and future consumption to maximize lifetime utility given their intertemporal budget constraint. The life-cycle profile of savings resembles a characteristic hump-shaped curve, with indebtedness occurring in early life and retirement depleting individual savings. The more the household income flow is hump-shaped, the higher the level of debt needed to smooth out consumption. Lifetime wealth that comprises lifetime income, owned assets, and their value is crucial for this intertemporal decision-making process.

The newer versions of these models introduced uncertainty together with a precautionary motive for saving (Skinner 1987). In the buffer-stock savings model (Deaton 1991; Carroll 1992), consumers define a target wealth-to-income ratio and adjust savings to precautionary motives, the impatience of consumers who heavily discount the future, and their borrowing constraints in imperfect credit markets. Consumers dissave whenever the wealth stock is above its target, which typically occurs during economic expansions, while economic recessions give rise to prudent behaviours triggered by pessimism towards employment, with savings tending to increase.

Relying on these micro-foundations, a special class of macroeconomic models performs simulations to test for symmetry of the housing wealth effects on consumption along the upward and downward trends of the business cycle. In these models, both housing and consumption figure in households’ utility, housing can be used as collateral for new loans, and house price fluctuations affect at once households’ borrowing capacity and the return from producing new houses (Iacoviello 2005; Iacoviello and Neri 2010). Surges in housing demand or in housing prices loosen the collateral constraint of borrowers and boost credit by the associated wealth effect, increasing access to consumption (Lambertini et al. 2013; Christensen et al. 2016; Kim and Chung 2016; Rubio and Carrasco-Gallego 2016). The asymmetric effects of housing booms and busts are then related to the extent of housing collateral constraints. Along the upward trend of the business cycle, house price increases expand housing wealth and smooth households’ collateral constraints, fuelling debt-driven consumption (Guerrieri and Iacoviello 2017). As soon as house prices start to decline, collateral constraints shrink consumption possibilities and accentuate the economic depression. In this context, expectations of rising house prices produce a quantitative impact on macroeconomic fluctuations, changing mortgage credit and consumption. Kuang (2014) models the connection between housing and credit cycles, emphasizing the reinforcing role that seems to exist between house prices, optimism, and credit, with the latter, in its turn, reinforcing the cycle of optimism and increasing house prices, producing a self-fulfilling prophecy. Burnside et al. (2016) who explored the role of social interactions among agents with heterogeneous beliefs broached the possibility that the recent steep rise in house prices corresponded to a speculative bubble. The housing market was shown to be sensitive to anticipated beliefs of macroeconomic developments and to generate business cycle fluctuations.

Shiller (2007) highlighted the need to consider behavioural features in order to understand housing markets and interpret the origins of the US house bubble. According to this author, there is a feedback mechanism by which past price increases nurture future price expectations until a first sudden drop in prices causes a bubble burst. The story told by the public and by the media contaminates households’ perceptions and generates, as Shiller terms it, a social epidemic of optimism for real estate, wherein the impression of owning a unique property whose value is about to increase leads households to raise consumption, boosting the economy. To focus on wealth effects, the empirical analysis should rely on microdata keeping in mind that housing dominates households’ portfolios. In a precursor to these studies, Engelhardt (1996) shows that while housing capital gains increase the propensity to consume, without symmetry in households’ responses to losses and gains, the losses increase other forms of non-housing savings and the gains leave consumers’ behaviour towards savings unchanged. Campbell and Cocco (2007) estimated the house price elasticity of consumption, distinguishing old homeowners whose elasticity was about 1.7 from young renters with a close to zero effect. In both cases, these effects were found to be more significant for credit-constrained households. Focusing on land prices in Japan, Muellbauer and Murata (2009) found negative wealth effects on consumption that they attributed to underdeveloped credit markets and to inheritance taxes favouring land and housing. Aron et al. (2012) confirmed this result in a comparison between Japan, the UK, and the USA and claimed that different degrees of credit market liberalization are responsible for different housing wealth effects for those countries and specifically for the negative effect in Japan’s case. Mian et al. (2013) estimated a positive housing wealth effect on consumption but with pronounced regional heterogeneity within the USA, with poorer regions or regions where households were more leveraged displaying a higher marginal propensity to consume out of housing. Arrondel et al. (2015) found the wealth effect changing across the wealth distribution for both housing wealth and financial assets, with it being higher at the bottom end of the wealth distribution and for financial assets.

A strand of the empirical literature has focused on the role of housing as collateral for new loans (Goodhart and Hofmann 2007). Oikarinen (2009) shows that house prices cause consumption loans to increase, accentuating the business cycle and the fragility of the financial sector. Gimeno and Martínez-Carrascal (2010), however, claim that while the collateral from house prices determines households’ borrowing capacity, fluctuations in house prices change housing wealth, define the level of households’ expenditure and borrowing, and even contribute to a sense of no over-indebtedness. For Cooper (2013), the additional collateral from changes in housing values impacts consumption of borrowing on constrained households, in line with Mian and Sufi (2014)’s results who maintain that constrained households that borrow are more prone to spend from housing wealth.

Common causes could also be explaining the correlation between house prices and consumption. A shock over an underlying variable, such as income expectations, would move house prices and consumption in the same direction (Attanasio et al. 2009). A permanent increase in factor productivity would affect both agents’ current wages and future wage expectations, causing a pro-cyclical movement of both consumption and house prices. A monetary policy shock could be an additional common cause (e.g. Robstad 2017).

3 Data and methodology

3.1 The Household Finance and Consumption Survey

This paper builds on household-level data collected from the first wave of the Household Finance and Consumption Survey (HFCS), which took place during the second quarter of 2010. The HFCS is run by the European Central Bank and aims to be representative of each country’s population. In the Portuguese case, 8800 households were interviewed and results were reported for 4404. The survey contains information on wealth, income, and socio-demographics such as the age of the head of the household and household composition, education, the region where the household lives, homeownership status, and total indebtedness, distinguishing mortgage debt from non-mortgage debt. The households’ financial constraints are also reported, along with negative past events.

The unit of observation of the empirical model is the household, but socioeconomic data were collected at the individual level. For that purpose, the adult male was identified as the household representative whenever possible, eliminating heterogeneity through gender (e.g. Costa and Farinha 2012). To capture housing wealth effects, the analysis focused on the population of homeowners corresponding to 2986 households.

3.2 Dependent and explanatory variables

To examine the effect that perceived house prices have on debt, this study considers the following dependent variables: total debt, mortgage debt, non-mortgage debt of households who hold mortgage debt at the same time, non-mortgage debt of households who do not hold mortgage debt, and a ratio of over-indebtedness. The first four variables capture households’ total outstanding liabilities measured in euros as reported by the HFCS.

The measure of risky indebtedness is a composite variable that combines indicators of excessive debt. The first indicator defines as extreme, a debt value 3 times higher than the household’s annual income. The second indicator classifies as extreme, a debt value that exceeds 75% of the total household wealth. The third measure compares debt service with household income and establishes the alarm threshold at 40% of this ratio. The following ratio was calculated for each of these thresholds:

where \( r_{ij} \) is the measure of over-debt for indicator \( j \) and household \( i \), \( R_{ij} \) is the ratio of type \( j \) over-debt of household \( i \), \( R_{j} \) is the threshold ratio defined for indicator \( j \), and \( R_{{{ \hbox{max} }j}} \) is the maximum value observed for indicator \( j \) across the household distribution. The ratio of risky debt for each household \( i \) is calculated as the average value of the three indicators:

This variable is positive for households displaying over-indebtedness. A common feature of all the dependent variables considered in this analysis is the fact that they are limited at zero and that the majority of the population is clustered at this boundary as reported in the next section.

The main explanatory variables capture the appreciation of the residential property along tenure years by comparing the “property value at the time of its acquisition” with the “current price of household’s main residence” as reported by the household. Two variables were considered: the rate of housing valuation which is the ratio between the main residence current price and at the time of its acquisition, and the average annual rate of housing valuation corresponding to the former ratio normalized by tenure years. The additional explanatory variables of this model are tenure years and the dummy variable homeownership controlling for households who have bought or built their main residence. Lastly, the variable housing initial equity measures the difference between the residential property price at the time of its acquisition and the amount of credit borrowed to purchase it.

Age, marital status, and education refer to features of the reference person. Dummy variables identify the marital status, discerning married, widow(er), and divorced (the reference group being the singletons), and the highest full education degree, distinguishing secondary education, and tertiary education (the reference group including up to a primary school diploma).

Types of household are captured through dummy variables and consider households with only adults, households with adults and dependants, and with one adult and dependants. Dependants are individuals younger than 25 years old who do not receive income, cohabit with the household and are not the household reference person or his spouse/partner, or his parent/grandparent. Further covariates are the number of dependants, the total number of individuals, and the number of employed adults, all in the household.

Household income aggregates all sorts of income received by household members during 2009, the year that precedes the interview, and is converted into logarithms. It includes regular income, namely employee income, income from self-employment, income from pensions and other regular social transfers, the outcome of household’s assets portfolio, comprising private business and financial assets, real estate property and other sources, and income from regular private transfers. To examine the extent to which the impact of income on debt differs between those who have a high school diploma and all the others, an interaction term between the two variables is considered. Total wealth consists of real and financial wealth including the value of real estates, vehicles, businesses, and valuables, the set of household deposits, bonds, pension plans, mutual funds, and other financial assets, and their values are converted into logarithms.

To assess the impact of a household’s financial status, the model considers the dummy variables credit constraints and past adverse change(s). Credit constraints follow the definitions from the Household Finance and Consumption Network (2013); thus, respondents classified as credit constrained are those who applied for a loan in the previous 3 years and were either totally or partially turned down, or received a lower amount than they had applied for. This dummy also comprises respondents who reported not having applied for a loan due to perceived credit constraints. Past adverse change(s) captures households who reported that at least one of its members had unfavourable job changes, a substantial reduction in their net worth in the 3 years that precede the interview, an unusually low income during the year reported in the interview, or an increase in regular expenses.

3.3 Debt and housing valuation

The Portuguese housing market is noticeable for the prevalence of homeownership. According to the HFCS, about 72% of Portuguese households held a residential property in 2010, a fact that can be ascribed to a poorly legislated and incipient housing renting market. Table 1 displays descriptive statistics for the models’ dependent and explanatory variables. The typical individual in this sample is a 56-year-old married male with basic education, owning his residential property for 22 years, a period along which this asset rose in value by a factor of 18.7 against an average annual valuation of 0.5. The household average annual income is 21,956 euros, while the average accumulated wealth is about 224,750 euros. Other interesting features concern the reporting of odd events, the majority of households revealed having had adverse changes in the recent past although only 2.9% denoted liquidity constraints.

Table 2 reports summary statistics for positive values of debt and over-debt along with the percentage of the population that has reported holding debt. Only 37% of the population held outstanding liabilities from a residential property, owing amounts that on average were above the average value of total debt held by 44.2% of the population. A meagre share of 7.3% of the homeowners only had non-mortgage debt, while 17.1% of Portuguese homeowners were over-indebted given at least one of the three criteria of excessive debt. These statistics point to dependent variables clustered at zero.

Table 3 displays average debt against quartiles of housing wealth and tenure years. There are evident similarities between the distributions of the rate of housing valuation and tenure years, the size of debt and risky debt decreasing from the bottom to the top of the distribution. The exception is only non-mortgage debt whose distribution exhibits an inverted U-shape with a peak at the third quartile. The distribution of debt by quartiles of the average annual rate of housing valuation describes an inverted U-shape with a peak at the second quartile. As a whole, the distributions suggest that the size of debt is associated with homeownership, that debt fades with time, and that the housing wealth effects on debt may differ. Buying a residential property seems to represent a considerable financial effort for Portuguese households, which is mainly felt immediately after its acquisition or when its valuation is low.

3.4 Methodology

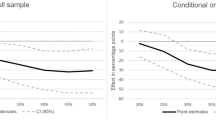

In the next sections, the housing wealth effect on debt is estimated by applying the Tobit model (Tobin 1958) that regresses a dependent variable with many observations clustered at a certain limiting value. Since the majority of the individuals in this sample do not hold debt (the median of the dependent variables is zero), the Tobit model is an appropriate framework to estimate these impacts. To avoid biased and inconsistent estimates in these types of limited value cases, linear regression models such as ordinary least squares which assume that the dependent variable is normally distributed cannot be used. The full sample can be considered with the maximum likelihood estimation of the Tobit model specified as follows:

where \( x \) is a vector of explanatory variables and \( \varepsilon_{i} \) is the normally and independently distributed error term. \( y_{i}^{*} \) is a latent variable that is observed for values greater than zero (positive values of debt and over-debt) and censored for the value zero. Its counterpart is the observed variable \( y_{i} \) defined as:

It is possible to calculate the unconditional and conditional marginal effects on the observed variable by considering or not the information that the observed variable is positive. These marginal effects are represented by the expressions:

where \( \gamma = f\left( z \right)/F\left( z \right) \) with \( f \) and \( F, \) respectively, the probability and the cumulative density functions, \( z = \beta 'x_{i} /\sigma , \) and \( \sigma \) is the standard error of the error term.

4 Model estimations

4.1 Total debt and mortgage debt

The first step is to estimate a baseline model that examines the overall relationship between perceived wealth from housing and mortgage debt, the most common form of debt among homeowners. Table 4 exhibits the maximum likelihood estimation results of the Tobit model and the marginal effects conditional on positive values of the latent variable for both total debt and mortgage debt. Features of the population are held at their mean values and then changed one by one, to estimate a ceteris paribus effect on the dependent variables of a variation in each attribute.

The set of results displays significant resemblances, exposing debt as mostly the consequence of purchasing a residential property. The estimates for the marginal effects of the housing variables were all significant, at least at the 1% level, thus corroborating the strong connection between homeownership and debt. However, the two main explanatory variables revealed opposite effects on households’ outstanding liabilities. Debt and mortgage debt were found to respond positively to the rate of housing valuation, and to having incurred costs with the purchase of the residential property, but to respond negatively to the average annual rate of housing valuation, to tenure years, and to initial equity. A unit increase in the rate of housing valuation was shown to expand debt and mortgage debt by 166 and 197 euros, respectively, among those with positive debt. Yet, a unit increase in the average annual rate of housing valuation displayed conditional marginal effects of − 7559 and − 8367 euros, respectively, on debt and mortgage debt. It seems that households perceive housing wealth differently if doing straight comparisons between the initial price of housing and its apparent valuation, or if normalizing this increase by the number of tenure years.

Two factors may be contributing to these findings. First, the most valued houses may be those bought in the distant past at relatively lower prices, their owners having a residual mortgage debt from the long-term contract celebrated at its purchase or having contracted new mortgage debt to refurbish it. Secondly, debt involves a planned financial effort that is assessed by households on an annual basis and compared to its annual market appreciation, and that comparison may incite paying off debt. A higher annual average valuation may encourage homeowners to write off their outstanding liabilities with what might have been understood as a reliable and promising asset. In this case, the effect of housing wealth on mortgage debt should encourage moving from a state of partial tenure to one of complete tenure, thus allocating wealth to what is seen as a solid investment.

The results on other variables that control for the impact of housing reinforce the contribution of homeownership to debt and mortgage debt. The negative effect from tenure years validates homeowners planning their housing financial effort within a given lifetime period. Not surprisingly, a lower initial financial effort was found to act in the same direction. Overall, homeowners’ debt is the reverse of being able to invest in housing and to consume it at the same time.

Further control variables in the model displayed the expected results. The most relevant finding is that a household’s composition moulds its outstanding liabilities: debt/mortgage debt intensifies among households in which several adults and dependants cohabit, so too with the number of dependants and with employed adults. An additional individual in the household decreased the value of debt holdings, possibly capturing poorer households in which many elements are forced to cohabit. In general, outstanding liabilities are higher among medium-size younger households with dependants, especially if the reference person has become divorced.

Income and wealth contributed to increasing the holdings of debt and mortgage debt, with the magnitude of the wealth effect exceeding that of income, perhaps reflecting a collateral effect. Nevertheless, the income of the highly educated was negatively related to their liabilities, pointing to heterogeneous responses of the population to debt. The inversion of the coefficient suggests some form of financial literacy, with higher education increasing risk aversion.

Debt is often related to credit constraints or unexpected and adverse events. Liquidity constraints were found to contribute positively to debt, suggesting reverse causality, namely households with higher outstanding liabilities reporting to be credit constrained. Another possible explanation, especially since credit constraints are not statistically significant for mortgage debt, is the use of credit cards and their high interest rates. The value of household debt was also found to be directly related to unexpected odd events, a result that discards precautionary savings motives across the Portuguese population and places debt as a buffer that allows households to keep up with past life patterns while income does not recover.

4.2 Non-mortgage debt

The estimations from the previous section may reflect causality and endogeneity, especially between house prices and mortgage debt. In fact, the possibility that increases in house prices push debt to a higher level cannot be excluded. However, by estimating a model for non-mortgage debt it is possible to focus on the effects of housing wealth on consumption. The results for non-mortgage debt are displayed in Table 5, distinguishing two dependent variables: outstanding non-mortgage liabilities of households that also hold mortgage debt (non-mortgage debt), and solely non-mortgage debt possibly implying that mortgage debt has already been paid off (only non-mortgage debt). The loss of statistical significance of the coefficients that capture the effects of housing wealth stood out clearly in the first model, indicating that the appraisal of housing wealth is not relevant for households deciding how much accumulated non-mortgage debt to hold when they still have outstanding liabilities with a mortgage. The estimates for non-mortgage debt revealed a changed scenario: across households with positive non-mortgage debt, a unit increase in the rate of housing valuation contributed to a decrease in debt of about 76 euros. The effects of the average annual rate of housing valuation were shown to be symmetric to the later ones, augmenting debt holdings by 2291 euros. Besides the inversion of the housing wealth coefficients, these are also symmetric to the estimations for total debt and mortgage debt, revealing reverse effects of housing wealth by type of debt. Our findings suggest that homeowners without outstanding liabilities from a costly and crucial consumption good—their residential property—respond to relatively higher annual valuations of the asset that most likely represents their largest wealth share by contracting new loans to increase consumption as if displaying a subjective backwards impatience. If impatience dominates households’ decisions, it is natural to expect the following confidence response: the perception of increased wealth increasing current outstanding liabilities with the purchase of consumption goods. Moreover, the results expose distinct effects of perceived wealth from housing on further loans depending on whether these are meant to invest in the main asset or to use on consumption goods after the accomplishment of the housing acquisition.

Home acquisition was found to limit households’ additional financial decisions, dropping non-mortgage debt holdings by 1103 euros. One extra tenure year helps households overcome their behavioural constraints, inducing additional loans to satisfy consumption needs. In contrast to the effect on mortgage debt, a higher initial housing equity displays a positive effect on consumption debt. When compared to the results for mortgage debt, the fact that the signs of the coefficients for the set of housing variables are inverted reveals housing as a special good for homeowners. Homeowners consume through an investment that retains their largest wealth share, possibly decreasing their cash-on-hand and limiting access to other consumption goods. When homeowners perceive the housing market to be signalling an increase in their lifetime savings, they feel they can adjust their consumption levels upwards, but to do so they need to demand additional credit. When contracting new loans, these households react as if anticipating the wealth effect is permanent. The fact that these results are only confirmed for those that do not hold outstanding liabilities with a mortgage reveals precautionary behaviours among Portuguese homeowners, who seem to take their chances with consumption based on housing wealth after having finished the investment on their lifetime security. The increase in mortgage debt may also correspond to a substitution effect from the increase in house prices, leading households to prefer to consume goods whose relative price has become cheaper and that is backed by the double nature of housing.

Liquidity-constrained households were predicted to hold higher non-mortgage outstanding liabilities, a puzzling fact that once again may relate to reverse causality or, on the other hand, to the use of credit cards by those that have less access to credit.

Socioeconomic variables seem to play a minor role in explaining the size of non-mortgage debt held by the fraction of the Portuguese population that does not hold mortgage liabilities. The exceptions were households with dependants and a number of employed adults, where both were found to be positively related to non-mortgage debt. However, the set of socioeconomic variables becomes relevant to explain the size of non-mortgage debt for households holding mortgage liabilities, debt increasing with income, and decreasing with age. Across the household distribution, a 1% increase in income produced an increase of about 864 euros on non-mortgage debt, as if a relative position at the top of the income distribution induced optimism about a household’s future income expectations and incited an increase in consumption through debt.

4.3 Over-indebtedness estimation results

About 17.1% of Portuguese households exhibited very high outstanding liabilities and were classified as over-indebted. The results for the estimations of over-debt are displayed in Table 6. As can be seen, the model contains fewer variables than the previous ones given the loss of statistical significance of several variables. A first overall impression is the resemblance between the signs of the coefficients for those estimations and those found for debt and mortgage debt. The rate of housing valuation was found to be positively related to the over-debt ratio, while the average annual rate of housing valuation, tenure years, and initial housing equity were negatively related to over-debt. The statistical significance of these coefficients corroborates homeownership as a relevant feature of over-indebtedness. Since tenure years contribute to eroding over-indebtedness, the risk of defaulting seems to be higher for households owning newer residential properties, indicating impatience as a reason for over-indebtedness.

When perception is measured as a relative concept—how much the residential property valuation was per year—and if the ratio of over-debt increases with the perception of housing valuation irrespective of tenure years, a risk-aversion behaviour similar to that found in debt and mortgage debt estimations emerges. It is as if a residential property that is annually relatively well valued triggers precautionary behaviours among households. Again, this indicates a better control of closer information than of a time distant one, with households’ perception becoming more accurate when comparing the mortgage debt annual interest costs to their annual housing valuation. Initial housing equity was shown to decrease the ratio of risky indebtedness, a result that reaffirms the contribution of housing to households’ liabilities and shows there is a greater likelihood of risky behaviours in adverse contexts.

Control variables partially replicated the results found for debt and mortgage debt, such as age decreasing the magnitude of over-indebtedness, or the number of employed adults increasing it. Total wealth was positively related to this ratio, signalling that financial institutions demand a warranty in exchange for loans and indicating that for a household it is difficult to hold debt above 75% of their aggregate wealth. In its turn, a 1% increase in income was seen to decrease the ratio of over-debt, which is most likely the consequence of having built this indicator from two income thresholds. It is worth noting the replication of results for past adverse changes and liquidity constraints, both statistically significant at the 1% level, and displaying positive effects, suggesting that risky behaviours are not necessarily deliberate but rather the result of unpredicted detrimental events such as unemployment.

Even if over-debt is the joint result of outstanding liabilities from a mortgage and consumption goods, the estimations point to housing as the main driver of risky debt. Housing is highly valued by homeowners who consume it and assume it as their lifetime investment. Occasionally, to own it they nearly default.

4.4 High- and low-income groups

The size of debt might also be associated with socioeconomic features of the population such as their relative income or relative wealth. Poorer households may depend more on credit to smooth consumption, especially when they anticipate an increase in future income within a context of economic growth. Nevertheless, the poorer may be more credit constrained, with the richer having easier access to debt from having collateral. In each case, dissimilar levels of income and wealth could lead to different debt responses to housing valuation. To test this, further estimations were performed for different groups of households classified either by their annual income or by wealth. Table 7 displays average amounts of debt and ratios of risky debt for households located at the top and at the bottom of the income and wealth distributions. For both variables, the top group is shown to hold higher amounts of debt, with larger disparities for average mortgage liabilities than for non-mortgage debt. A higher income level reduces over-indebtedness, while higher wealth increases it.

The estimations for non-mortgage debt were performed for the 20th and 90th income percentile and are listed in Table 8. Additional estimations took into account extreme levels of households’ wealth; however, the majority of the model variables became statistically non-significant. Except for homeownership, the two models exhibit the same sign for the coefficients of housing wealth and are in line with estimations for the total population; and, apart from tenure years, their magnitude is considerably higher for the bottom income population. Households who earn less seem to be more impatient, presenting relatively higher credit demands for consumption, suggesting that the effect of housing wealth tends to be felt more intensely by the spectrum of the population that is constrained in their access to consumption goods. The result that homeownership increases non-mortgage debt among the group of low-income households but decreases it among the rich reinforces the notion that residential property is used to smooth poorer households’ consumption. In addition, while wealth is shown to increase debt holdings among the poorer, it has a negative effect on the upper-income group, confirming that collateral effects are more relevant for poorer households.

The estimations of the ratio of risky debt by income and wealth groups displayed more statistically significant results for wealth than for income differences and are replicated in Table 9. The main difference between the two extreme wealth quartiles is the magnitude of the coefficients, with the poorer exhibiting larger absolute values for the coefficients and relatively larger than the baseline model. This suggests that if the driver of over-indebtedness is impatience related to the valuation of the main asset, the poor tend to be more cautious than the rich with regard to controlling their average annual rate of housing valuation. The warrants that financial institutions require to concede loans may be responsible for these findings, since by being less demanding with households that own valuable assets these institutions may be contributing to their risk of default.

5 Conclusion

This study tested at the household level, the assumption that housing wealth as appraised by homeowners can mould their decision on how much debt to hold. Two different measures of wealth perception were built based on the relative appreciation of housing price, both were shown to be strongly related to the amounts borrowed by households for mortgage and/or non-mortgage purposes, and significant in explaining over-indebtedness. The results proved to be conditioned by the variable chosen as the proxy of housing wealth and by the type of debt responding to these perceptions. Non-mortgage debt, which is a more unsafe form of debt, reacts positively to the average annual rate of housing valuation but negatively to its absolute value. This would suggest that households that over time experience comparatively higher valuations of their housing tend to feel confident and contract new loans for consumption purposes, with housing market behaviour feeding their impatience. The estimations for risky debt, in their turn, indicated it mainly mirrored mortgage debt, suggesting that if over-debt is the outcome of a bad decision, it will be mostly related to housing acquisition. It is worth noting that the significance of past adverse changes to explain unsafe debt holdings since these are most likely a consequence of an inability to predict decreases in income from hardship such as unemployment periods.

Estimations by classes of income and wealth, focusing on the extreme tail ends of these distributions, showed dissimilar debt responses to housing wealth from distinct population groups, even if both groups exhibit a significant housing wealth effect. Low-income homeowners were predicted to be relatively more indebted than high-income ones and to apparently resort more to housing as collateral for consumption. The wealthier displayed higher levels of over-indebtedness, suggesting that the perception of a valuable collateral can lead to unsafe behaviours nurtured by financial institutions.

This paper has several practical implications. First, households that face a relatively rapid valuation of their main residence will tend to contract additional loans to increase consumption, indicating that homeowners update the information on their intertemporal human wealth in response to perceived movements in the housing market. This optimistic effect from house price appreciation will be felt more strongly within the lower, possibly more liquidity-constrained, income group. Second, if over-debt is related to owning a house and having contracted long-run debt to purchase it, being richer tends to increase the relative amount of risky loans, while those with lower real and financial wealth most likely display lower risky ratios because their collateral imposes upper limits to indebtedness. In this case, the optimism may belong to the financial institutions which, when granting loans, treat those with lower wealth as riskier and are more willing to lend higher amounts to richer households since they deem their risk of default to be lower.

The policy implications of this work are mainly two. First, it is important to establish rules for financial institutions’ evaluation of housing when the purpose is to accept it as collateral for credit lending. Since it is not easy to monitor the housing market, a better alternative could be to consider the valuations that are recorded by the fiscal authorities for mortgage tax purposes. Secondly, since over-indebtedness seems to be related to the constraints imposed by housing acquisition, credit market conditions for housing purchase should be reconsidered to decrease the likelihood of default. This would imply a tightening of the existing requirements for granting loans against declared wealth and should be especially more pronounced with respect to what has been practised within the group of wealthier households. Nevertheless, since the largest share of Portuguese households are homeowners, these credit regulation measures need to be offset by policy measures that can enlarge the housing rental market as for instance creating a public supply of housing for rental purposes.

References

Aron J, Duca JV, Muellbauer J, Murata K, Murphy A (2012) Credit, housing collateral, and consumption: evidence from Japan, The U.K., and The U.S. Rev Income Wealth 58:397–423

Arrondel L, Lamarche P, Savignac F (2015) Wealth effects on consumption across the wealth distribution: empirical evidence. Working paper series 1817. European Central Bank

Attanasio OP, Blow L, Hamilton R, Leicester A (2009) Booms and busts: consumption, house prices and expectations. Economica 76:20–50

Burnside C, Eichenbaum M, Rebelo S (2016) Understanding booms and busts in housing markets. J Polit Econ 124:1088–1147

Campbell JY (2006) Household finance. J. Finance 61:1553–1604

Campbell JY, Cocco JF (2007) How do house prices affect consumption? Evidence from micro data. J Monet Econ 54:591–621

Carroll CD (1992) The buffer stock theory of saving: some macroeconomic evidence. Brook Pap Econ Act 23:61–185

Case KE, Quigley JM, Shiller RJ (2005) Comparing wealth effects: the stock market versus the housing market. Adv Macroecon 5:1–32. https://doi.org/10.2202/1534-6013.1235

Christensen I, Corrigan P, Mendicino C, Nishiyama SI (2016) Consumption, housing collateral and the Canadian business cycle. Can J Econ 49:207–236

Cooper D (2013) House price fluctuations: the role of housing wealth as borrowing collateral. Rev Econ Stat 95:1183–1197

Costa S, Farinha L (2012) Households’ indebtedness: a microeconomic analysis based on the results of the households’ financial and consumption survey. Financial Stability Report. May. Banco de Portugal

Deaton A (1991) Savings and liquidity constraints. Econometrica 59:1221–1248

Engelhardt GV (1996) House prices and home owner saving behaviour. Reg Sci Urban Econ 26:313–336

Friedman M (1957) A theory of the consumption function. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Gimeno R, Martínez-Carrascal C (2010) The relationship between house prices and house purchase loans: the Spanish case. J Bank Finance 34:1849–1855

Goodhart C, Hofmann B (2007) House prices and the macroeconomy: implications for banking and price stability. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Guerrieri L, Iacoviello M (2017) Collateral constraints and macroeconomic asymmetries. J Monet Econ 90:28–49

Household Finance and Consumption Network (2013) The Eurosystem Household Finance and Consumption Survey—methodological report for the first wave. European Central Bank. http://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/ecbsp1en.pdf

Iacoviello M (2005) House prices, borrowing constraints, and monetary policy in the business cycle. Am Econ Rev 95:739–764

Iacoviello M, Neri S (2010) Housing market spillovers: evidence from an estimated DSGE model. Am Econ J: Macroecon 2:125–164

Kim JR, Chung K (2016) The role of house prices in the US business cycle. Empir Econ 51:71–92

Kivedal BK (2014) A DSGE model with housing in the cointegrated VAR framework. Empir Econ 47:853–880

Kuang P (2014) A model of housing and credit cycles with imperfect market knowledge. Eur Econ Rev 70:419–437

Lambertini L, Mendicino C, Punzi MT (2013) Leaning against boom–bust cycles in credit and housing prices. J Econ Dyn Control 37:1500–1522

Lambertini L, Mendicino C, Punzi MT (2017) Expectations-driven cycles in the housing market. Econ Model 60:297–312

Mian A, Sufi A (2014) House price gains and U.S. household spending from 2002 to 2006. NBER working papers 20152. National Bureau of Economic Research

Mian A, Rao K, Sufi A (2013) Household balance sheets, consumption, and the economic slump. Q J Econ 128:1687–1726

Modigliani F, Brumberg RH (1954) Post-Keynesians economics. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick

Muellbauer J, Murata K (2009) Consumption, land prices and the monetary transmission mechanism in Japan. CEPR discussion papers 7269. CEPR discussion papers

Oikarinen E (2009) Interaction between housing prices and household borrowing: the Finnish case. J Bank Finance 33:747–756

Robstad Ø (2017) House prices, credit and the effect of monetary policy in Norway: evidence from structural VAR models. Empir Econ 542:461–483

Rubio M, Carrasco-Gallego JÁ (2016) Liquidity, interest rates and house prices in the euro area: a DSGE analysis. J Eur Real Estate Res 9:4–25

Shiller RJ (2007) Understanding recent trends in house prices and home ownership NBER working papers 13553. National Bureau of Economic Research

Skinner J (1987) Risky income, life cycle consumption, and precautionary savings. J Monet Econ 22:237–255

Tobin J (1958) Estimation of relationships for limited dependent variables. Econometrica 26:24–36

Acknowledgements

The authors are deeply thankful to the editor and the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful and insightful comments on an earlier version of this article.

Funding

This work was supported by the FCT (Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, Portugal) under BRU-IUL (Business Research Unit - Instituto Universitário de Lisboa), Grant No. UID/GES/00315/2013.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Camões, F., Vale, S. I feel wealthy: A major determinant of Portuguese households’ indebtedness?. Empir Econ 58, 1953–1978 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-018-1602-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-018-1602-9