Abstract

Purpose

The mean reported healing rate after meniscal repair is 60 % of complete healing, 25 % of partial healing and 15 % of failure. However, partially or incompletely healed menisci are often asymptomatic in the short term. It is unknown whether the function of the knee with a partially or incompletely healed meniscus is disturbed in the long term. The purpose of this study was to assess the long-term outcomes of meniscal repairs according to the initial rate of healing.

Methods

Forty-one consecutive meniscal repairs were performed between 2002 and 2003. The median age at the time of surgery was 22 years (9–40). There were 25 medial and 16 lateral menisci. When present, all ACL lesions underwent reconstruction (61.3 % of cases). According to Henning’s criteria, by Arthro-CT at 6 months, twenty cases had healed completely, seven partially healed and four cases healed incompletely.

Results

At a mean follow-up of 114 ± 10 months, 31 patients were retrospectively followed for clinical and imaging assessments. Objective IKDC score was good in 92 % of the cases (17 IKDC A, 8 B and 2 C). The mean KOOS distribution was as follows: pain 94.3 ± 9; symptoms 90.9 ± 15; daily activities 98.7 ± 2; sports activities 91.1 ± 14; and quality of life 91.5 ± 15. Twenty-three patients displayed no signs of osteoarthritis when compared to the non-injured knee, six patients had grade 1 osteoarthritis and two grade 2. The subjective IKDC score did not decrease with time (ns). Moreover, there were no differences between lateral and medial menisci (ns), in stable or stabilised knees (ns). The initial meniscal healing rate did not significantly influence clinical or imaging outcomes (ns). Four patients with no healing underwent a meniscectomy (12.9 %).

Conclusion

Arthroscopic all-inside meniscal repair with hybrid devices may provide long-term protective effects, even if the initial healing is incomplete.

Level of evidence

Case series, Level IV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Arthroscopic meniscal repair has been the procedure of choice for many years to treat traumatic vertical lesions occurring in a vascularised area. The goal of meniscal repair should include early pain relief, healing of the tear and prevention of secondary lesions and joint degeneration.

Several studies showed that meniscal repair results in less degenerative changes than partial or subtotal meniscectomy [20, 23, 26]. Despite this knowledge, a meniscectomy is performed in 65 % of vertical meniscus tears during ACL reconstruction [18].

Current meniscal repair techniques reduce the tear to a stable configuration, with 60–80 % complete healing [4, 8, 21]. Repaired menisci, even partially healed, are often asymptomatic in the short- to mid-term [6, 16].

There is no evidence in the literature that incompletely healed menisci continue to function properly as load distributors protecting the weight-bearing surfaces.

The purpose of this study was to assess the long-term outcomes of meniscal repairs performed in stable or stabilised knees. The hypothesis was that partially or unhealed repaired menisci would clinically deteriorate with time, and that the incidence of articular degenerative changes would be higher when compared to completely healed repaired menisci, according to Henning’s criteria.

Materials and methods

During 2002 and 2003, 41 meniscal tears were repaired in 23 men and 18 women. The median age at the time of meniscal repair was 22 years (range 9–40 years). This is a long-term retrospective study of patients whose preliminary clinical outcomes and healing rates were published 1 year after repair [21].

The meniscal tears involved 29 right knees and 12 left knees, and the tears were located in 25 (61 %) medial and 16 lateral menisci (39 %). All tears were vertical, located in the red–red or red–white zone. At the time of meniscal repair, patients with ACL deficiency also underwent arthroscopically assisted bone-patellar tendon-bone autograft reconstruction (59 %). The demographics of the patients are summarised in Table 1. The median length of the meniscal tear was 20 mm (range 15–35).

Thirty-eight repairs were carried out using FastFix® hybrid devices (Smith & Nephew, Andover, MA); three suture repairs were performed using a combination of #0 non-braided absorbable mattress sutures with an outside-in technique and FastFix® devices. The median number of sutures or hybrid devices needed was 3 (range 1–7).

After repair, the involved leg was placed in a brace for 4 weeks. Full weight bearing was immediately allowed with the brace in full extension. Flexion was limited to 90° during 4 weeks. ACL reconstruction did not alter the rehabilitation.

Running, swimming, and cycling were begun at 3 months. Return to full athletic participation was authorised at 6 months.

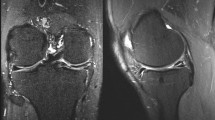

The criteria for meniscal healing were based on arthro-CT, according to Henning [9], in which a tear was classified as incompletely healed if the heal was over at least 50 % of the thickness of the tear. A failure was defined as healing of less than 50 % of the thickness at any point over the length of the tear.

Six months after the procedure, twenty cases displayed complete healing, seven were partially healed and four healed incompletely. Although a meniscal width reduction after repair was found in the initial study, a correlation with clinical outcomes or degenerative changes were found in the long term.

The median follow-up period was 9.7 years (range 9–10 years). At the time of follow-up, both the injured and uninjured knees were examined; pain, range of motion, stability and swelling were recorded. Patients returned Lysholm, International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) and KOOS forms, including a general questionnaire determining their current function. Failure of repair was defined as patients developing symptoms of joint line pain and/or locking and/or swelling requiring repeat arthroscopy and partial or subtotal meniscectomy.

Bilateral weight-bearing radiographs, including AP, lateral, schuss or Rosenberg and skyline views at 30° of flexion, were performed preoperatively and at follow-up.

They were reviewed according to the grading by Ahlback and Rydberg [2].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with Statview® (v 5.0, SAS Institute Inc.). For the comparison of quantitative and qualitative variables, the Student-Fisher method was used. For the analysis of the results according to healing rates (three subgroups), the Kruskal–Wallis test was used. To compare the quantitative variables, the coefficient of correlation was used. The level of significance was set to 0.05.

Results

At a median follow-up of 9.7 years, a total of 31 patients were reviewed. Ten patients were lost to follow-up. Four patients showed no healing and a recurrence of symptoms, and underwent a subsequent meniscectomy of the medial meniscus at a median follow-up of 33 months (range 12–46 months) after meniscal repair and concomitant ACL reconstruction, leaving 27 patients for final analysis.

The median and mean Lysholm scores were 100 (range 80–100) and 94.7 ± 8, respectively. The median and mean IKDC scores were 94 (range 62–100) and 89.8 ± 11, respectively.

The KOOS distribution was as follows: pain 94.3 ± 9; symptoms 90.9 ± 15; ADL 98.7 ± 2; sports activities 91.1 ± 14; and quality of life 91.5 ± 15 (Fig. 1).

There was no deterioration in the clinical outcomes with time when comparing IKDC scores at 1 year and at final follow-up (ns).

On clinical examination, the mean active flexion was 139° (range 120–150). There were no extension lag signs. The objective IKDC score was grade A in 17 patients, B in eight and C in two.

According to the Ahlback osteoarthritis scoring system, when compared to the contralateral healthy knee, nineteen patients (70 %) displayed no degenerative changes, six (22.5 %) had a grade 1 joint space narrowing of the repaired compartment and two (7.5 %) had a grade 2 joint space narrowing.

Patients with radiological degenerative changes (≥grade 1) gave less favourable results on the KOOS form than patients without changes (ns).

In both subgroups of medial and lateral repair, clinical and radiological results were statistically similar (ns). There were no differences among stable or stabilised knees (ns).

There was no correlation between the initial healing rate and clinical outcomes at follow-up (IKDC, Lysholm, KOOS scores, ns, Fig. 1). The initial healing rate did not influence chondral degenerative changes at follow-up (ns). There were six postoperative complications: four failures, as noted above, underwent secondary meniscectomies, and two experienced secondary rupture of the ACL requiring reconstruction (with confirmation of the meniscal healing during arthroscopy).

Discussion

The most important finding of this study was that the clinically successful repaired menisci exhibited good long-term clinical results and a low to moderate incidence of osteoarthritis in this small group of stable or stabilised knees.

Studies publishing long-term outcomes of meniscal repair have been also reviewed (Table 2) [1, 5, 7, 10–13, 15, 17, 19, 22, 24, 25, 27]. Some deteriorating outcomes after repair have been published, with increased secondary meniscectomy rates in the long term, especially with the use of meniscal arrows [11, 24]. With other techniques, successfully repaired menisci may remain so with time. In the reference papers listed in Table 2, the failure rate ranged from 3 to 32 %.

Although these studies published results with arrows, outside-in or inside-out techniques, this is the first study to report long-term outcomes of meniscal repairs using all-inside hybrid devices.

It has been shown that the long-term consequence of meniscectomy is an increased incidence of osteoarthritis, whereas successful meniscal repairs seem to lower these rates [20, 26]. In the literature review of long-term results after meniscal repair, the incidence of osteoarthritis ranged from 8 to 35 % (Table 2).

Melton et al. [15] compared three subgroups of patients having either meniscal repair, an intact meniscus or meniscectomy during ACL reconstruction, at a median follow-up of 10 years. Patients with meniscal repair had a mean IKDC of 84.2 compared with a mean score of 70.5 (p = 0.008) in patients who had undergone meniscectomy and 88.2 (p = 0.005) in patients with intact menisci.

McGinty [14] showed that 62 % of their patients with a subtotal meniscectomy had degenerative chondral lesions, compared to 36 % of their patients treated with partial meniscectomy, at mid-term follow-up. Stein et al. [26] compared arthroscopic partial meniscectomy and meniscal repair at 3 and 8 years. They found better clinical results and fewer osteoarthritic changes in the repaired group, especially in young patients.

Paxton et al. [20] published a literature review comparing meniscal repair and partial meniscectomy. In the long-term, meniscal repair was associated with higher Lysholm scores and less degeneration than partial meniscectomy.

Different rates of healing are reported after meniscal repair. The rate of complete healing after meniscal repair is only around 60 % in the literature [2, 28].

Ahn et al. [3] reviewed meniscal repairs among 140 patients undergoing simultaneous arthroscopic ACL reconstruction. Among them, 84.3 % of meniscal repairs were completely healed at the second-look arthroscopy. The clinical success rate was 96.4 % because patients in the incompletely healed group showed no clinical symptoms associated with residual meniscal tears. The status of the incompletely healed meniscus and its association with the risk of increasing failure rate with time and long-term protective effect on cartilage are still unknown. In our study, there were no decreasing outcomes with time, even for partially healed menisci, and the repaired meniscus, if still present, seemed to retain a biomechanical function protecting cartilage from degenerative changes.

Limitations of this study were that 10 patients were not available at 10 years, and that the number of patients involved was small. Nevertheless, the preoperative and operative data of the 10 patients lost to follow-up were comparable to the 31 reviewed patients, avoiding some major bias. A 75 % follow-up rate for a 10-year clinical study in a young population is acceptable when compared to other studies.

Overall, a partial healing of a repaired meniscus is not detrimental in the long term if the patient remains pain free and/or does not need a subsequent meniscectomy.

Conclusion

A long-term protective effect of the meniscus against degenerative joint disease might be preserved after repair, even if the initial healing is incomplete. The incidence of joint space narrowing is low. Therefore, repair of a ruptured meniscus is recommended whenever possible, despite risks of partial healings or outright failure.

References

Abdelkafy A, Aigner N, Zada M, Elghoul Y, Abdelsadek H, Landsiedl F (2007) Two to nineteen years follow-up of arthroscopic meniscal repair using the outside-in technique: a retrospective study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 127:245–252

Ahlback S, Rydberg J (1980) X-ray classification and examination technics in gonarthrosis. Lakartidningen 77:2091–2093, 2096

Ahn JH, Lee YS, Yoo JC, Chang MJ, Koh KH, Kim MH (2010) Clinical and second-look arthroscopic evaluation of repaired medial meniscus in anterior cruciate ligament-reconstructed knees. Am J Sports Med 38:472–477

Ahn JH, Wang JH, Yoo JC (2004) Arthroscopic all-inside suture repair of medial meniscus lesion in anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knees: results of second-look arthroscopies in 39 cases. Arthroscopy 20:936–945

Brucker PU, von Campe A, Meyer DC, Arbab D, Stanek L, Koch PP (2011) Clinical and radiological results 21 years following successful, isolated, open meniscal repair in stable knee joints. Knee 18:396–401

Cannon WD Jr, Vittori JM (1992) The incidence of healing in arthroscopic meniscal repairs in anterior cruciate ligament-reconstructed knees versus stable knees. Am J Sports Med 20:176–181

Eggli S, Wegmuller H, Kosina J, Huckell C, Jakob RP (1995) Long-term results of arthroscopic meniscal repair. An analysis of isolated tears. Am J Sports Med 23:715–720

Grant JA, Wilde J, Miller BS, Bedi A (2012) Comparison of inside-out and all-inside techniques for the repair of isolated meniscal tears: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med 40:459–468

Henning CE, Lynch MA, Clark JR (1987) Vascularity for healing of meniscus repairs. Arthroscopy 3:13–18

Johnson MJ, Lucas GL, Dusek JK, Henning CE (1997) Isolated arthroscopic meniscal repair: a long-term outcome study (more than 10 years). Am J Sports Med 27:44–49

Lee GP, Diduch DR (2005) Deteriorating outcomes after meniscal repair using the meniscus arrow in knees undergoing concurrent anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: increased failure rate with long-term follow-up. Am J Sports Med 33:1138–1141

Logan M, Watts M, Owen J, Myers P (2009) Meniscal repair in the elite athlete: results of 45 repairs with a minimum 5-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med 37:1131–1134

Majewski M, Stoll R, Widmer H, Muller W, Friederich NF (2006) Midterm and long-term results after arthroscopic suture repair of isolated, longitudinal, vertical meniscal tears in stable knees. Am J Sports Med 34:1072–1076

McGinty JB (1996) The importance of the meniscus. Am J Knee Surg 9:109

Melton JT, Murray JR, Karim A, Pandit H, Wandless F, Thomas NP (2011) Meniscal repair in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a long-term outcome study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 19:1729–1734

Morgan CD, Wojtys EM, Casscells CD, Casscells SW (1991) Arthroscopic meniscal repair evaluated by second-look arthroscopy. Am J Sports Med 19:632–637 (discussion 7–8)

Muellner T, Egkher A, Nikolic A, Funovics M, Metz V (1999) Open meniscal repair: clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings after twelve years. Am J Sports Med 27:16–20

Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD (2012) Treatment of meniscus tears during anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 28:123–130

Owen J (2005) 12.9 Year results of meniscal repair using an arthroscopically assisted inside-out technique. J Bone Joint Surg 87-B:151

Paxton ES, Stock MV, Brophy RH (2011) Meniscal repair versus partial meniscectomy: a systematic review comparing reoperation rates and clinical outcomes. Arthroscopy 27:1275–1288

Pujol N, Panarella L, Selmi TA, Neyret P, Fithian D, Beaufils P (2008) Meniscal healing after meniscal repair: a CT arthrography assessment. Am J Sports Med 36:1489–1495

Rockborn P, Gillquist J (2008) Results of open meniscus repair. Long-term follow-up study with a matched uninjured control group. J Bone Joint Surg Br 82:494–498

Shelbourne KD, Dersam MD (2004) Comparison of partial meniscectomy versus meniscus repair for bucket-handle lateral meniscus tears in anterior cruciate ligament reconstructed knees. Arthroscopy 20:581–585

Siebold R, Dehler C, Boes L, Ellermann A (2007) Arthroscopic all-inside repair using the meniscus arrow: long-term clinical follow-up of 113 patients. Arthroscopy 23:394–399

Steenbrugge F, Verdonk R, Verstraete K (2002) Long-term assessment of arthroscopic meniscus repair: a 13-year follow-up study. Knee 9:181–187

Stein T, Mehling AP, Welsch F, von Eisenhart-Rothe R, Jager A (2010) Long-term outcome after arthroscopic meniscal repair versus arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for traumatic meniscal tears. Am J Sports Med 38:1542–1548

Tengrootenhuysen M, Meermans G, Pittoors K, van Riet R, Victor J (2011) Long-term outcome after meniscal repair. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 19:236–241

van Trommel MF, Simonian PT, Potter HG, Wickiewicz TL (1998) Different regional healing rates with the outside-in technique for meniscal repair. Am J Sports Med 26:446–452

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pujol, N., Tardy, N., Boisrenoult, P. et al. Long-term outcomes of all-inside meniscal repair. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 23, 219–224 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-013-2553-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-013-2553-5