Abstract

The Internet has the potential to reduce search frictions by allowing individuals to identify faster a larger set of available options that conform to their preferences. One market that stands to benefit from this process is that of marriage. This paper empirically examines the implications of Internet diffusion in the USA since the 1990s on one aspect of this market—marriage rates. Exploring sharp temporal and geographic variation in the pattern of consumer broadband adoption, I find that the latter has significantly contributed to increased marriage rates among 21–30 year-old individuals. A number of tests suggest that this relationship is causal and that it varies across demographic groups potentially facing thinner marriage markets. I also provide some suggestive evidence that Internet has likely crowded out other traditional meeting venues, such as through family and friends.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The last 15 years have witnessed a dramatic explosion in the growth of the Internet. The first wave of this technology—dial-up connection—was widely introduced in the USA in the early 1990s, whereas the second—broadband—began to diffuse after the 1996 Telecommunications Act.Footnote 1 This second wave has arguably been more influential for the evolution of daily communications, activities, and transactions (NTIA 2004, 2010). The online environment has become a close alternative to traditional offline markets, with the additional potential advantage of efficiency. It enables access to a virtual space that supplies consumers with an abundance of product-specific options in a short amount of time. Given that in a traditional offline setting search is often impeded by the substantial difficulty to identify all the available alternatives, the Internet is thought to offer a centralized solution to this problem, thereby reducing search frictions.

Two markets that are characterized by such frictions, and therefore stand to benefit from the growing presence of the Internet, are those of labor and marriage. To date, a number of studies have documented the active role of the Internet in the worker-firm matching process.Footnote 2 The market for romantic partners functions in ways similar to the labor market. Individuals are in search of a partner, and there is difficulty to identify potentially suitable mates, uncertainty regarding match quality, an optimal stopping rule for search, and turnover. While economists have acknowledged the theoretical potential of the Internet to affect search and matching in the marriage market as well, little progress has been made due to data limitations (Stevenson and Wolfers 2007; Hitsch et al. 2010). This paper aims to fill this gap by testing whether the diffusion of this technology has had a measurable impact on one of the aspects of the marital search process—the transition into first marriage. To my knowledge, this is the first paper to empirically address this link.

A preliminary glance in the data suggests that an association between flows into marriage and Internet diffusion exists and is striking. According to Rosenfeld and Thomas (2012), this technology is the second most popular venue of meeting a partner after traditional offline social networking, especially among young people. Among couples that met in 1994–1998, 3.9 % report having met online for the first time. Interestingly, this number has risen to 11 and 20 % for couples that met between 1999–2003 and 2004–2006, respectively.Footnote 3 This is unsurprising, given that the last two periods also coincide with the beginning of an era of dramatic growth in high-speed and broadband Internet technologies that has profoundly transformed the social landscape.

To offer more rigorous evidence on the link between the Internet and marriage rates, I exploit the sharp geographic (state) and temporal variation in the pattern of home broadband adoption between 1990 and 2005. Conditioning on a number of individual and state, time-varying characteristics in a setting with state, year fixed effects, and state-specific trends, I find that expansions in Internet availability are associated with significant increases in marriage rates in the benchmark 21–30-year-old white population. The effect is also sizeable and significant for African-Americans, a minority group potentially facing a relatively thinner marriage market. Quantitatively, the estimates suggest that the realized increase in broadband penetration throughout this period has contributed to higher marriage rates in the benchmark population by roughly 13–33 % relative to what they might have been in the absence of this technology. A series of falsification tests based on the timing of the advent of broadband as well as an instrumental variable strategy provide strong suggestive evidence in favor of the causal interpretation of this result.

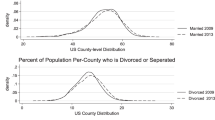

Whereas the analysis focuses on the transition into first marriage, the Internet may have been a powerful force in shaping other marital decisions as well. For instance, if marriages initiated through the Internet are of higher quality, they will likely be more durable. Consequently, the incidence of divorce and remarriage may decrease. While the Current Population Survey (CPS), my main data source, does not provide information to study these outcomes appropriately, I use the available data to evaluate whether the Internet has impacted on the propensity of the ever married population to be in a formal relationship at all times. I find that such an effect exists and is positive, namely that Internet expansion is associated with higher propensity to be married as opposed to be separated/divorced. However, it is not possible to distinguish whether this is due to first marriages being more durable or to remarriage being facilitated by the presence of the Internet.

While the empirical analysis largely focuses on establishing whether this technology can improve matching efficiency, plausible mechanisms underlying this potential relationship are also discussed. In particular, I show that online dating usage is associated with increases in marriage rates and I discuss suggestive evidence that the Internet has played a displacing rather than complementary role in the social arena, likely crowding out other traditional forms of search such as through friends and family. Furthermore, it appears that the presence of the Internet has had a negative impact on social capital accumulation, as it has significantly reduced the time young people spend on socializing and physically communicating.

This work complements related research by Hitsch et al. (2010), which relies on data from an online dating service to infer revealed mate preferences. One key finding is that the match outcomes in the online dating market appear to be approximately efficient in the sense that they are the outcomes that would arise in an environment with no search frictions. Nevertheless, because of data restrictions, the authors cannot address whether online meetings result in offline partnerships and subsequently to marriage. This is one direction where this paper contributes.

This research makes two other important contributions. First, it relates to the literature on determinants of the timing of first marriage. This is a particularly crucial decision for women since it is critically tied to human capital accumulation and career considerations.Footnote 4 Moreover, it is worth highlighting that, whereas the median age at first marriage rose precipitously throughout the 1970s and 1980s, these trends interestingly began to level off in the mid-to-late 1990s, exactly when advanced Internet services emerged.Footnote 5 While these trends cannot be viewed in isolation from the relative strength of other factors affecting fertility timing or educational and occupational opportunities, it is still interesting to identify whether recent technological advancements, such as the Internet, can partly account for the relative acceleration in marriage rates among 21–30-year-old individuals post-1990 compared to what otherwise would have been expected, given the preexisting declining marriage propensities observed in this group.

Finally, these findings complement the recent, policy-relevant research on the economic implications of broadband, a technology whose benefits will still take time to be fully revealed. Since its advent, a wide range of policies subsidizing Internet infrastructure have arisen and resources have been devoted to promote universal deployment. Studies that sought to evaluate such benefits have predicted faster economic growth for broadband-using communities, emphasizing the importance of this technology for regional development (see Lehr et al. 2006; Gillett and Lehr 1999; Crandall and Jackson 2001; Forman et al. 2012; and Greenstein and McDevitt 2009). Establishing that there are also indirect effects on social aspects, such as family formation, that have implications for the operation of the labor market, highlights the impact of the Internet as a technology with far-reaching effects.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes a conceptual framework to motivate the relationship between Internet diffusion and marriage flows. Section 3 presents the data, and Section 4 details the empirical strategy. Section 5 discusses the results, addresses identification concerns, and presents a heterogeneity analysis of the main findings. Section 6 provides a discussion of potential underlying mechanisms, and Section 7 concludes.

2 Conceptual framework

Search frictions play an important role in the functioning of labor and marriage markets and are typically studied in the context of dynamic search models. This framework, in particular, has been extensively used to model the marital search process (Becker 1973, 1974; Becker et al. 1977; Montgomery and Trussell 1986; Burdett and Coles 1997). In a basic infinite horizon search model, individuals search for suitable partners and receive offers drawn from some known distribution. Search continues until a partner is found whose quality equals or exceeds an endogenously determined reservation value. In this setup, the instantaneous exit rate to marriage depends on the probability of receiving a marriage proposal and on the probability of its acceptance. The latter is in turn a function of the reservation value, which is determined by parameters such as search costs, discount rate, reservation utility in single state and the probability of receiving an offer.

Standard search theory predicts that, all else equal, higher search costs will increase the probability of marriage. This is because they tend to reduce the value of continued search as single relative to marriage thereby lowering the minimum quality (reservation) value the individual would accept. Nevertheless, an increase in the offer arrival rate has a theoretically ambiguous effect on the propensity to marry. On the one hand, it directly increases the probability of receiving an offer and therefore the probability of quitting search to enter marriage. On the other hand, however, the increased likelihood of receiving an offer enhances the expected value of continued search as single and thereby the required reservation threshold. The latter effect implies a decline in the probability that a marriage offer will become acceptable.

Within the above framework, the Internet could be perceived as a means of decreasing search frictions by reducing the cost of search and/or increasing the offer arrival rate. Diminished search costs could occur for several reasons. In an offline, decentralized environment, searching for a suitable partner can be a lengthy process accompanied by uncertainty regarding match quality and psychological costs associated with personal encounters and potential rejections. An online centralized marriage market instead could resolve a number of these issues. This is because it allows for targeted search along certain desirable characteristics while the users retain a degree of anonymity. Within a short time period, a set of plausible matches can be identified, which is possibly larger than the set formed via the individual’s offline social network. While the latter is an enticing feature of the online market, it may still entail additional costs in the form of greater time and effort investment from the side of the user, not only to learn how to navigate through a computerized system but also, more importantly, to disentangle truly compatible types among the expanding pools of identified candidates. This is especially relevant, given the degree of misrepresentation and lying that occurs online with respect to individual physical appearance or marital status.Footnote 6 Moreover, such time and effort costs are over and above any explicit monetary costs for the usage of these online services. If the decrease in search costs and the associated net gains in efficiency indeed occur and are significant enough, then, all else equal, we would expect a negative relationship between Internet diffusion and marriage rates.

Nevertheless, another plausible and likely simultaneous to the reduction in search costs effect of Internet diffusion is an increase in the offer arrival rate. In this case, search theory predicts that the probability of marriage could be affected in any direction. Greater exposure to potential mates through the Internet will enhance the frequency of offers and therefore the likelihood of marriage. However, as the offer probability rises, so does the desired reservation quality. Consequently, the likelihood of accepting an offer declines as well as the probability of marriage. Hence, the net impact of an Internet-induced increase in the frequency of offers on marriage is ambiguous.

These arguments essentially suggest that, from a theoretical standpoint, the overall effect of Internet diffusion on marriage is a priori unclear, as each of the underlying proposed mechanisms can influence its likelihood in a potentially different direction.Footnote 7 The goal of the subsequent sections is to address the empirical counterpart of this question, namely uncovering the potential impact of Internet expansion on marriage propensities and highlighting the implications for the marital responses of various demographic groups with likely different search costs and arrival offer rates within their own marriage markets.

3 Data and descriptive statistics

3.1 Data

To establish a link between Internet diffusion and marriage patterns, I exploit variation in marriage rates and broadband penetration within states over time and across states. The main analysis relies on data from two sources. First, to measure marriage propensities, I use the information on the current marital status of the respondents from the March CPS supplements (King et al. 2010; years 1990–1995 and 2001–2006). The outcome of interest is whether the individual has ever been married. The baseline sample consists of approximately 180,660 white (non-Hispanic) males and females aged 21–30 years old. This primary age group includes individuals who have recently been or currently are in the marriage market and so are more likely to be affected by current marriage and labor market conditions. Hence, this outcome likely captures transitions into first marriage. Because there are important differences in the marriage patterns of whites (non-Hispanics), African-Americans (Seitz 2009), and Hispanics, I choose to study the decisions of these groups separately. First, I focus on the behavior of the white non-Hispanic population, and in Section 5.4, I discuss heterogeneous effects for other racial groups.

Based on the abovementioned definition, online Appendix Table 1 describes age-specific marriage rates across states at four points in time: in 1990 and 1995, when Internet technology and, in particular, broadband was virtually nonexistent; in 2001, at the very early stages of broadband; and in 2006. Clearly, marriage propensities have been falling over time, a phenomenon that was particularly prevalent in the mid-1970s and 1980s. There is, however, substantial state heterogeneity in the way marriage rates have evolved over time. While in certain states marriage rates continued to fall rapidly (Arizona, Kentucky, Louisiana, Tennessee), in others, the fall happened at the same fairly constant rate (Alabama, California, Georgia, Ohio) or even at a much slower pace (Delaware, DC, New York, Colorado). While this preliminary pass-through in the data is purely descriptive, the goal of this paper is to examine to what extent these trends are causally affected by the simultaneous growth in broadband Internet technology.

Figure 1 tracks the propensity to marry by the age of 40 for cohorts aged 21 years old in 1980, 1985, 1990, 1995, and 2000.Footnote 8 First of all, as is depicted, marriage propensities grow substantially less after the age of 30. By then, the vast majority of individuals have already been married once. Therefore, ages 21–30 years are the appropriate range to focus on. Moreover, while the propensity to marry at relatively younger ages has significantly fallen overtime, the propensity to marry by the age of 30 and even more by the age of 40 has fluctuated much less. This is an important observation because it implies that the decay in marriage rates for this focal group mostly refers to a marriage delay rather than an overall rejection of the concept of marriage. In this sense, search theory provides an appropriate framework to address variations in the marital search decision (see Loughran 2002 for a similar argument).

I supplement the data on marriage rates from the CPS with information on state-level broadband diffusion as well as other state covariates. The broadband market is an industry that has been growing very rapidly since the 1996 Telecommunications Act facilitated entry of more telecommunication service providers. The data on broadband penetration is obtained from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Statistical Reports on Broadband Deployment. These reports summarize data on high-speed Internet subscribership gathered through the Form 477 that qualifying carriers are required to file twice a year. I focus on broadband adoption by households since home is the most typical point of Internet access. Information on residential broadband penetration first became available by the FCC in December 2000 and is recorded annually since then. While deployment started taking place after 1996, the FCC does not publicly report any state-specific statistics on diffusion referring to the 1996–1999 period.

I measure the evolution of home broadband diffusion during 2000–2005 by the number of residential high-speed lines per 100 people in a state.Footnote 9 Since this information is only available at the state level, it naturally restricts the definition of the local marriage market to also be the state. Because the CPS records individual behavior in the March of each year while data on broadband adoption are collected later in December, I assume that marriage patterns in a given year are affected by the level of Internet availability recorded in the December of the previous year. For instance, marriage rates recorded in March 2001 are assumed to be influenced by broadband availability as measured in December 2000. This effectively means that I use the changes in the evolution of broadband between 2000 (the first year the FCC makes available such data) and 2005 to explain changes in marital patterns between 2001 and 2006.

Because I only observe changes in Internet diffusion and marriages after the advent of broadband, the importance of preexisting trends will not be adequately accounted for. For this reason, I take advantage of the fact that prior to 1996, home broadband penetration was virtually nonexistent, and I supplement the 2001–2006 marriage sample with CPS years 1990–1995 and setting, hence, the number of pre-1996 residential broadband lines to 0.Footnote 10 Therefore, the final sample spans the years 1990–1995 (pre-broadband era) and 2001–2006 (post-broadband era).

Online Appendix Table 1 summarizes state-specific changes in this measure during the period of study. As is evident, there is significant variability in deployment within and across years and states. In 2005, there were on average about 14 lines per 100 people up from 0.9 in 2000, but across states, adoption varied from 0.14 lines in 2000 in Mississippi to 3.18 lines in New Hampshire. Nevertheless, even though the speed of diffusion within the examined 5-year period has been remarkable, penetration took place much more slowly in certain states (Iowa, Kentucky, S. Dakota) than in others (New Jersey, Connecticut, Maryland).

There are two main conceptual issues associated with this measure of Internet diffusion. First of all, it is a measure that captures evolution in the availability of this technology and not individual Internet usage per se which, in particular, pertains to the focal group aged 21–30 years old. While this can be perceived as a limitation of the analysis, broadband diffusion remains to be an informative and policy-relevant parameter and is likely more exogenous than the respondent’s own Internet usage.

Second, broadband diffusion focuses on high-speed Internet subscribership and, as such, it does not directly reflect variation in dial-up usage over the period of study. The dial-up access was a predominant form of Internet connection until the early 2000s, but since then, its incidence leveled off and subsequently plummeted. According to statistics published by the (NTIA 2004, 2010), there has been a dramatic crowding out of dial-up connection by broadband: the number of households with high-speed or broadband connections grew from 9.9 million in September 2001 to 22.4 million in October 2003. Dial-up connections declined by 12.7 % or 5.6 million households during the same period. In 2009, only 5 % of all households were using dial-up while 64 % were broadband subscribers. In addition, the decline in the share of dial-up users has been more than offset by the expansion of broadband Internet users, leading to a net increase of Internet usage from home at the extensive margin.Footnote 11 The shift towards broadband reflects the fact that the latter allows faster access to a greater volume of information, thus significantly improving the online experience of the users.

The crowding out of dial-up connection and the advent of broadband have likely transformed the economic as well as social landscape and, in particular, the way people connect and communicate at all levels. Broadband is associated with more intensive use of the Internet from consumers and also with their engagement to a wider variety of online activities. This is especially true for communication activities such as emailing or sending instant messages (NTIA 2010). The pumped up consumer demand for new virtual activities related to broadband deployment has further accelerated business innovation by introducing new consumer applications and services (ITU 2012). While the significant crowding out of dial-up connection does not necessarily imply that broadband is more effective at improving matching, it is suggestive that it may have at least facilitated and intensified the use of the Internet as an intermediary for partner search. Increasingly, more people access the Web than before and can resort to online resources as a fast and possibly more efficient way of meeting others (via email, instant messaging, chat rooms, online dating). At the same time, the number of social networking and online dating sites offering such services has been rapidly expanding.Footnote 12 For these reasons, broadband rather than dial-up penetration is potentially a more relevant measure of Internet penetration during the period of study and even more so for younger individuals, who tend to use broadband more intensively and whose marital choices are the outcome of interest.

Finally, the analysis is supplemented with a broad set of aggregate covariates, controlling for factors that could affect both broadband deployment and marriage decisions. I include two sets of state-level, time-varying covariates. First, to account for the fact that broadband deployment is influenced by a number of demographic and economic aspects of the local market, I introduce controls that capture economic prosperity, business activity, and the demographic composition of the state. These are population density, the fraction of the population that is nonwhite, the fraction of the population in various age groups, log GDP, median household income, unemployment rate, as well as the number of firms operating in high-tech sectors that are presumably more prone to adoption of advanced Internet technology (Prieger 2003; Stevenson 2006, 2009; Forman et al. 2012).Footnote 13

In addition to these controls, I include a set of state covariates that are race and age-specific, aiming at describing relevant economic opportunities and demographic and regional factors correlated with both broadband deployment and marriage decisions among 21–30-year-old individuals (Blau et al. 2000). These covariates are as follows: the sex ratio which is defined as the number of men over the number of women in a given group, female and male wages, schooling, and the fraction of people residing in a metropolitan area as a proxy for urbanicity. For the baseline model detailed in the next section, this set of controls represents state means calculated for 21–30-year-old white individuals. When other population subgroups are discussed in Section 5.4, these controls are appropriately adjusted to reflect the characteristics (in terms of age, race, and/or education) of the group of interest. Population density, urbanicity, and the sex ratio are also proxies for local marriage market conditions. Population density and urbanicity could be viewed as influencing the probability of meeting a partner, while the sex ratio the extent of local competition for age and race-eligible partners.Footnote 14

Online Appendix Table 2 provides summary statistics for the abovementioned covariates in selected sample years. Online Appendix Table 3 displays the results from a regression of household broadband penetration during 2000–2005 on the list of state covariates previously mentioned as well as state and year fixed effects. Coefficients of variables that are statistically significant at conventional levels are only reported. The results suggest that population density, the age composition of the state, its level of education, as well the strength of the high-tech sector are among the most important determinants of broadband expansion. As some of these determinants likely influence marriage patterns, the empirical analysis controls for all these potentially confounding factors.

3.2 Internet expansion and marriage rates: preliminary evidence

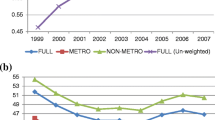

Figure 2 provides the first pass-through in the data highlighting the source of variation employed in order to identify the impact of Internet diffusion on marriage rates. As formally explained in the next section, this effect is identified from variation in marriage rates and Internet penetration within states over time and across states. This strategy importantly eliminates biases due to state-specific time-invariant unobservable factors correlated with the level of broadband deployment and marriage rates. Figure 2 associates changes in the share of (white) ever married 21–30-year-old individuals between 2001 and 2006 to changes in broadband diffusion within states in these years, hence netting out fixed unobservable state characteristics. This figure essentially previews my main result: marriage rates grew on average more in states with greater increases in broadband penetration.

Figure 3 displays the difference in the change in marriage rates between 2001–2006 and 1990–1995 graphed against the difference in the change in broadband diffusion between 2000–2005 and 1990–1995 (essentially zero). This approach eliminates state-specific time-invariant unobservable factors that are correlated with changes in marriage rates and broadband expansion. The figure suggests an even steeper positive relationship between the variables of interest once such factors are accounted for. While the preliminary evidence presented in these figures is suggestive of a potentially causal link between the two variables, the remaining of the paper seeks to more formally establish whether this is indeed the case.

Change in % of ever married population (2001–2006 versus 1990–1995). The figure displays the difference in the change in the share of 21–30-year-old white ever married population between 2001–2006 and 1990–1995 in a given state graphed against the change in broadband diffusion between 2000–2005 and 1990–1995 in the same state. Broadband diffusion is measured by the number of residential high-speed lines per 100 people in a state. Data sources include annual March CPS supplements (cross sections 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005) and FCC statistical reports on broadband deployment (years 2000 and 2005). Broadband diffusion was essentially zero in 1990 and 1995. Population estimates by state are obtained from the Census Bureau

4 Econometric methodology

The search model briefly outlined in Section 2 suggests that the propensity to marry in a given period depends on an exogenously determined offer arrival rate and a reservation value. The first component is a function of the local marriage market conditions influenced by, for instance, the sex ratio or the degree of local Internet availability, whereas the second component is affected by elements such as the cost of soliciting offers, the individual’s discount rate, single-state reservation utility, as well as the offer arrival rate. Assuming that these variables are in turn functions of observable and unobservable individual characteristics, the propensity to marry can be estimated in reduced form by the following linear probability model:

where Married i s t is a dichotomous variable that is equal to 1, if respondent i residing in state s in year t has ever been married and 0 otherwise.Footnote 15 Vector X i s t contains basic demographic individual characteristics such as the respondent’s education as well as whether she resides in a metropolitan area.Footnote 16 To capture the impact of age on the marriage behavior I add age dummies. Their addition allows interpreting the dependent variable as the propensity to marry by a given age. Z s t is a vector of state variables including population density and age and race-specific state covariates, such as sex ratio, wages and schooling. The set of all variables forming vector Z is described in Section 3.1 Internet s t is the variable of interest measured by the number of residential high-speed Internet lines per 100 people in a given state and year.

φ s and ρ t are state and year fixed effects respectively. The former capture any state-specific time-invariant characteristics that simultaneously influence broadband deployment and marriage rates. Year fixed effects control for unobserved factors affecting the likelihood of marriage that are common to all states in a given year. Hence, the parameter of interest, β 1, is solely identified from within-state variation in broadband penetration and marriage over time. Cross-sectional variation does not contribute to the estimates. As long as the fixed effects do not vary over time, this approach will yield unbiased estimates of β 1. Finally, Eq. 1 is estimated using the available sampling weights. The standard errors are corrected to take account of the clustered structure of the error term as well as the fact that Internet diffusion varies at a higher level of aggregation than the individual units. To obtain heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors, I cluster them by state and year.

The estimation of Eq. 1 using fixed effects will provide useful inference about the causal impact of Internet penetration on marriage, if Internet diffusion is truly exogenous. This assumption will not hold if, for instance, there are unobserved factors that trend over time within a state and are correlated with broadband diffusion and marriage or if states that were already experiencing increasing marriage rates were more likely to adopt the new technology. Then, the estimated effect would simply reflect a continuation of this preexisting trend. To assess these possibilities, I supplement (1) with state-specific linear time trends. In this case, Internet-related marriage effects are identified using a within-state variation in the marriage rate (relative to the national trend) after netting out state-specific time trends. While this is a more conservative estimation strategy, as it eliminates strong cross-sectional variation not only in the levels but also in the trends in marriage and Internet diffusion, it will importantly highlight whether omitted variable bias due to gradually evolving unobserved state characteristics is driving the main results. This strategy will also address the importance of preexisting state-specific conditions. The fact that the baseline sample dates back to 1990 and includes 5 years prior to the advent of broadband (1990–1995) will allow to more credibly identify such trends (Wolfers 2006).

I address further potential identification concerns related to the omitted variable bias in four different ways. First, I consider models with region-year and division-year interactions in order to investigate the importance of different sources of spatial heterogeneity. These terms will sweep out between-region (division) variation, and therefore, estimates will be based on variation solely within each region (division) over time. Second, using the specific timing of the diffusion of broadband (largely after the 1996 Telecommunications Act), I construct a series of falsification checks, aiming at testing whether broadband diffusion in the 2000s can predict marriage rates and other marriage-related outcomes in the years when broadband did not exist. Third, I investigate whether the identified effect is biased by the presence of reverse causality driven by immigration decisions of married individuals towards states with a certain level of Internet penetration. Fourth, I implement an instrumental variable strategy where Internet diffusion is instrumented with household telephone diffusion in 1955. The rationale for the instrument is based on the hypothesis that Internet diffusion may follow long-standing patterns in the adoption of other communication technologies and, in particular, that of the telephone. While the possibility of endogeneity cannot be completely ruled out, the results from Section 5.2 seem to overwhelmingly support the causal interpretation of the estimated effects.

5 Results

5.1 Baseline estimates

Table 1 reports the results from the estimation of specification (1). Recall that the sample spans the years 1990–1995 (pre-broadband era) and 2001–2006 (post-broadband) and consists of 21–30-year-old white respondents. The covariates are progressively introduced in the estimated model. Column 1 presents the results when no individual or state covariates are included. In column 2, gender and age structure controls are introduced, which are significant determinants of broadband penetration and marriage decision. Individual controls for education and metropolitan status are subsequently added in column 3, and state covariates are introduced in column 4. Columns 1 to 5 present the estimates using the pooled sample and columns 6 to 9 the estimates of Eq. 1 by gender. While the flows into marriage are the combined result of actions of both sides of the market, it is possible that a state variable, such as Internet penetration, has a differential effect on men and women.

The results uniformly indicate that broadband diffusion has significantly increased marriage rates among 21–30-year-old individuals. The coefficient of interest in the pooled sample is 0.0052 and implies that one extra broadband line per 100 people is associated with an increase in the proportion of ever married individuals by 0.52 percentage points. When state-specific trends are allowed for, the coefficient further increases to 0.0075. This result suggests that the relationship between Internet penetration and marriage rates is not spurious and, furthermore, that unobserved factors associated with rising marriage propensities have actually made states less likely to adopt the new technology. Quantitatively, the estimated effects presented in columns 4 and 5 (preferred specifications) imply that an increase in broadband diffusion by 1 line from the 2000–2005 average of 7.9 lines (that is an increase of 12.6 %) is associated with an increase in marriage rates by approximately 1.2–1.7 % relative to the 2001–2006 mean (0.435). Gender-specific marriage responses are qualitatively similar to the pooled estimates. While in the plain fixed effects model the estimates are somewhat lower for women, this discrepancy disappears once state-specific trends are introduced. This suggests that unobserved heterogeneity is likely more important for the female decision to marry.Footnote 17

Online Appendix Table 4 displays analytically coefficient estimates of all the remaining covariates included in Eq. 1. They overall have the expected signs. In particular, marriage decisions are significantly affected by the local marriage market conditions proxied by urbanicity and the sex ratio. A higher number of men relative to women decrease the chances that a woman remains single, while the opposite is true for men. To allow for this differential effect of the sex ratio on the propensity to marry by gender, the pooled benchmark model further includes an interaction of this variable with a gender dummy. Moreover, the odds of getting married are positively related to the population density of the state and to urbanicity. This result is likely due to the fact that the size of the market is an increasing function of the population of the state, while more urban areas are typically more densely populated, which would also tend to increase the meeting rate. While urbanicity is important regardless of gender, it appears that the density is a stronger determinant of the marriage decision of women. Finally, the size of the age-eligible marriage population also matters: the greater the share of younger individuals (aged 16–35 years old) in the total population, the higher the marriage rates would be. Regarding the significance of the local economic environment for marriage decisions, the results suggest that factors such as the income or development level (measured by GDP) of the state have no significant effects on the propensity to marry. Finally, areas where the high-tech economy is more developed display lower marriage rates.Footnote 18

5.2 Identification of a causal relationship

The identifying assumption of the empirical strategy is that, conditional on all covariates, the diffusion of broadband Internet is exogenous. This assumption can be violated due to the presence of unobserved heterogeneity that is not adequately controlled for by the time-varying state covariates, state and year fixed effects, as well as state-specific linear time trends. In this section, I further assess the validity of the exogeneity assumption by performing a series of tests. These will enhance our understanding of whether a causal interpretation can be attached to the baseline estimates.

To start with, in columns 2 to 5 of Table 2, I explore a different source of identification that relies on variation in marriage rates and Internet diffusion within regions and census divisions. In columns 2 and 3, I introduce interactions between the four census regions and the year fixed effects and with and without allowing respectively state-specific linear time trends. In columns 4 and 5, I instead consider interactions between the period fixed effects and the nine census divisions. These spatial interactions are a flexible way of accounting for changes in underlying regional or division-level factors that trend arbitrarily over time. As can be seen, the estimates survive these stringent tests even when state trends are introduced, hence providing support in favor of the robustness of the baseline effects (Table 1).Footnote 19

Another source of bias could be due to reverse causality induced by the moving decisions of more marriage-oriented people towards states with a certain level of Internet penetration. To investigate this issue, I use the limited information in the March CPS on the migration status of the respondent in the past year to define a moving dummy for whether the individual switched states since last year. When this term is included in the baseline specifications in columns 6 and 7 (Table 2), the coefficient of interest is only negligibly affected. Cross-state migration, instead, has an individually significant effect on marriage propensities.Footnote 20

In Table 3, I use the timing in the advent of broadband to perform a series of falsification tests for the validity of the exogeneity assumption. Broadband Internet’s wide diffusion was primarily realized after 1995. As a result, logic suggests that there should not be any association between future adoption and marriage propensities prior to that point. If a systematic relationship is detected, then this indicates that the exogeneity of broadband deployment is likely violated.

To implement this falsification strategy, I study how changes in broadband diffusion between 2000 and 2005 affect changes in marriage propensities between 1985 and 1990.Footnote 21 The years 1985–1990 refer to a period when not only broadband Internet did not exist but even basic Internet technology had not yet broadly diffused among households. Hence, if Internet penetration is truly exogenous, there should be no association between future Internet adoption and marriage patterns long before this technology was adopted by consumers. Column 2 presents the results from a regression akin to that in column 1, where marriage propensities in 1985–1990 are projected on broadband diffusion in 2000–2005 as well as the remaining covariates over the same period. The estimate is nearly 0 and statistically insignificant. In columns 3–6, I repeat the same exercise using 1985–1990 changes for a different set of dependent variables that are highly correlated with marriage: fertility measured by the propensity to have a child in the population aged 21–30 years old, the share of 21–30-year-old individuals that have obtained a college degree, the propensity of those aged 25–35 years old to divorce, and finally, the state’s sex ratio pertaining to 21–30-year-old whites.Footnote 22 In all cases, future adoption has no predictive power on the outcomes measured before advanced or even basic Internet telecommunications emerged. These results provide further supportive evidence of the exogeneity condition.

5.2.1 Instrumental variable analysis

Finally, as an additional check, I supplement my main findings with the results from an IV specification. To construct my instrument, I consider the hypothesis that Internet diffusion may follow long-standing patterns in the adoption of other communication technologies by households and, in particular, that of the telephone (see Stevenson 2006 for a similar argument). To test this hypothesis, I study the relationship between modern broadband diffusion and residential telephone adoption in 1955.Footnote 23

In online Appendix Fig. 1, I plot state broadband diffusion in 2005 against that predicted by telephone ownership in 1955. The figure unsurprisingly displays a strong predictive power of these historical patterns of telephone adoption and lends support to the null that Internet penetration resembles the historical adoption of similar types of innovations. Furthermore, this strong relationship is not exclusive to 2005 but extends to all sample years.

The fact that the diffusion of the telephone several decades ago can predict contemporaneous Internet diffusion implies that there are certain state-specific characteristics that drive overall technological penetration, which are relatively stable over time. These characteristics could reflect land/housing features, basic infrastructure, or attitudes and cultural preferences for innovation.Footnote 24 While it is not unlikely that these determinants are also correlated with marriage, the fact that they have been stable over time indicates that any underlying endogenous relationship should be captured by the presence of state fixed effects already included in the baseline model. In other words, if openness to innovation and social liberalism have steadily shaped technological change and family formation in certain states over time, then these bias-inducing unobserved factors should be accounted for by the inclusion of state fixed effects precisely because of their stable nature.

The first and second stage results are presented in Table 4. Notice that because telephone adoption in 1955 is time-invariant while contemporaneous Internet adoption is not, the instrument is interacted with year fixed effects to allow for time variation. Year fixed effects remain in the model as separate covariates. The first-stage estimates suggest that telephone adoption in 1955 is a significant predictor of current Internet diffusion, as already indicated by online Appendix Fig. 1. Moreover, the value of the F statistic implies that the instrument is strong, while the Hansen J statistic further suggests that it is independent of the error process. Turning to the second stage, the IV estimate is significant and in-line with the ordinary least square (OLS) effects presented in Tables 1 and 2, although quantitatively larger: an increase in the level of broadband adoption by one additional line per 100 people results in an increase in marriage propensities by 1.3 percentage points.Footnote 25 Overall, the IV results in combination with the specifications and falsification tests presented in Tables 2 and 3 are suggestive of a causal relationship between Internet diffusion and marriage rates.Footnote 26

5.3 Interpretation of the baseline effects

How can we interpret the results presented in Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4, and what do they imply about the trajectory of marriage rates post-1990? To evaluate the magnitude of the estimated effects, I will use as a lower bound of the impact of Internet expansion the baseline estimate of 0.0052 (Table 1, column 4) and as an upper bound the IV estimate of 0.013 (Table 4). These coefficients indicate an increase in marriage rates by 0.52–1.3 percentage points when broadband penetration increases by one additional line per 100 people. This is a 0.9–2.4 % increase from the 1990 average (0.548), which corresponds to the time when Internet technology had not yet diffused among consumers. Since broadband penetration increased from 0 to 14 lines per 100 people between 1990/1995 and December 2005, extrapolating the measured coefficient to current (2006) circumstances implies that marriage rates are currently higher by roughly 13.2–33.2 % from what they might have been if this technology did not exist.Footnote 27

Alternatively, consider another potential thought experiment. The share of ever married white individuals aged 21–30 years old was 0.734 in 1974 and 0.548 in 1990. This means that during this 16-year period, marriage rates fell by 18.6 percentage points. Now, assume that nothing else (other than Internet diffusion) changes in the subsequent post-1990 period (relative to the 1974–1990 period) and that marriage rates continue to fall by the same absolute amount between 1990 and 2006. This would imply that the 2006 marriage rate among 21–30-year-old individuals should have been 0.362. The data, however, indicate that the actual share of ever married individuals in this age group is 0.412. That is, the current level is 13.8 % higher relative to the theoretically predicted level of 0.362. Hence, under the strong assumption that the same conditions prevailed between 1990 and 2006 as they did between 1974 and 1990, these back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that Internet diffusion could entirely account for the relative deceleration in the long-standing trend towards rapidly falling rates of marriage among 21–30-year-old individuals.

5.4 Heterogeneity analysis

The analysis presented so far indicates that Internet diffusion has played an important role in transforming one of the aspects of the marriage market, namely the transition into first marriage. The results from a number of tests suggest that this relationship is also causal. However, it is unlikely that the effect has been uniform across the entire population. As the costs and benefits of search vary across demographic groups along with their opportunities to access the Internet, we might observe broadband diffusion having a more pronounced effect on the marital outcome of certain groups—possibly facing thinner markets or more difficulties in meeting potential mates such as same-sex couples or racial minorities—versus others. In Table 5, I explore such possibilities.Footnote 28

In columns 2 and 3, I assess whether Internet diffusion has similarly altered the marital decisions of younger (aged 16–20) and older (aged 31–35) groups relative to the 21–30-year-old core population. The results suggest that there is a significant impact on the marriage response of younger individuals. An increase in Internet expansion by one additional line per 100 individuals is associated with an increase in marriage propensities of 16–20-year-old individuals by 0.5–0.7 percentage points. This corresponds to a roughly 8–11 % increase in marriage rates in this group from the 1990 average (0.065). There is no discernible effect among relatively older individuals. This is not surprising as the majority of respondents in this group, and especially women, have already been married at least once by the age of 30.

Columns 4 and 5 present the results by education group. The estimates for college graduates as opposed to individuals not having a college degree are not statistically different from each other, suggesting that the Internet has affected the search behavior of both groups in a similar manner. In columns 6 and 7, I ask whether populations in urban areas profit more from greater Internet access than populations residing outside of the central city. The effect in this case could theoretically go either way. In urban areas, the Internet is more accessible but potentially more expensive. There are also more opportunities to meet people offline. However, because the set of options expands, it may take longer to locate the most appropriate match. On the other hand, in less urban areas, deployment has been slower but Internet access has been possibly more affordable, while the pool of potential partners is relatively limited. The results suggest that all individuals have responded to Internet diffusion regardless of their location status. Nevertheless, respondents in central cities have altered their marriage behavior significantly more in response to broadband expansion relative to respondents residing in less centrally located areas.Footnote 29

Finally, in columns 8 and 9, I explore whether marriage responses of other racial groups resemble those of whites. If some of these populations perceive themselves as facing thinner marriage markets and Internet helps to alleviate this concern, then expanding adoption may substantially improve matching efficiency for these groups. I find that Internet penetration has contributed to increased marriage rates among (non-Hispanic) Blacks but not among Hispanics. While the IV estimate for the latter group is sizeable, it is statistically insignificant. The effect on the black population is quantitatively similar to the effect on the white marriage rates. The presence of broadband is associated with an increase in black marriage rates by 0.50–1.7 percentage points, which amounts to a 1.3–4.5 % increase from the 1990 level (0.377).Footnote 30

5.5 Other outcomes

If the Internet has successfully affected transitions into first marriage, a natural question is whether it has also shaped other marital outcomes such as remarriage and divorce. CPS only reports the current marital status of the respondent and therefore does not distinguish between the first and subsequent marriages. This means that I cannot explicitly relate Internet diffusion to remarriage or ever divorced rates. For this reason, I compute another potentially informative statistic: whether individuals aged 25–35 and 36–55 years old, respectively, are currently married as opposed to divorced or separated. This variable is meant to capture the propensity to be matched at all times conditional on ever been married. I would expect a positive relationship between Internet diffusion and these quantities, if the Internet (i) either allows individuals to establish more suitable and therefore lengthier first matches or (ii) facilitates post-breakup marital search. Case (ii) is associated with higher propensity to enter faster another formal relationship given separation.

Table 6 displays the results. The estimates suggest that greater Internet adoption has not only induced more marriages among 21–30-year-old individuals but has also increased the overall propensity of individuals to be in formal relationships. This is true for both age groups. Future research, relying on more suitable data, should shed some light on whether this result reflects lengthier first marriages and/or faster remarriage.Footnote 31

6 Discussion

The key result of the empirical analysis is that Internet technology has contributed to more marriages in recent years. The objective of this section is to elaborate on the potential channels through which such a transformation has taken place. In particular, two relevant mechanisms are discussed. First, how people use the Internet to look for a partner, and second, whether online methods have crowded out more traditional forms of search. The answer to these questions is seriously complicated by the lack of relevant information in the large publicly available datasets. For that matter, since the CPS supplements do not provide any such information, I turn to a number of alternative sources.

Regarding the usage of online resources for partner search, the September 2005 survey released by the Pew Internet and American Life Project as well as by Dutton et al. (2008) provide some preliminary information on the ways respondents employ the Internet to meet people. According to Dutton et al. (2008), 49 % of the romantically linked couples that were surveyed met through an online dating website, 13 % through chat rooms, 12 % via instant messaging, and 12 % via social networking websites. Also, other ways were reported such as emailing or browsing for information about the local singles scene. It is interesting to note that among the couples who reported having met online, more than 50 % responded that they have done so via a way other than a dating website. Hence, it is important to emphasize that, although dating through organized matchmaking sites seems to be an easy and efficient way of meeting people (Hitsch et al. 2010), individuals appear to be using online resources in a much broader way when looking for a partner. Having said this, the baseline estimates (Table 1) can be interpreted as the overall effect of direct and indirect ways the Internet is utilized to look for a partner, from online dating to searching online for offline singles events.

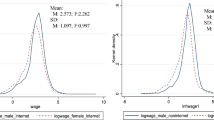

I provide more rigorous evidence on the link between online dating usage and marriage by using related information from the Pew Internet surveys.Footnote 32 A question on the usage of online dating sites for partner search was asked during the 2000 and 2002–2006 surveys. This information was organized in state-year averages and merged with the baseline CPS sample. Table 7 (A) presents results from estimation of Eq. 1 using state-level online dating usage as the covariate of interest in lieu of Internet adoption. The estimate suggests that, conditional on state and year fixed effects as well as state-specific linear time trends, growing utilization of online dating services is associated with higher marriage propensities. In particular, an increase in usage by 1 percentage point implies a statistically significant increase in marriage propensity by 7.8 percentage points. This suggests an increase in the share of ever married 21–30-year-old individuals by roughly 17 % relative to the mean.Footnote 33

The abovementioned estimate implies that this new form of social intermediation has been effective at improving matching efficiency. Has it displaced or complemented, however, other more traditional forms of search? Preliminary descriptive evidence supportive of a crowding out effect is offered by Rosenfeld and Thomas (2012). Using information on how a sample of romantically linked individuals first met, they show that some of the most traditional ways of meeting partners experienced significant declines post-1995. These include meeting through friends, co-workers, family, school, the neighborhood, and church. The Internet instead gained unambiguously in importance and in particular among homosexual couples. While these conclusions are drawn from plain data tabulations, the mere fact that nearly all offline forms of meeting have been in decline during the Internet era suggests that the Internet might have played a displacing rather than complementary role in the social arena.

I provide further statistical evidence in-line with the abovementioned finding using time use data on the socializing habits of single young Americans aged 21–30 years old. This information is obtained from the American Time Use Survey (ATUS) (Hoffert et al. 2013) and covers the period 2003–2006. I construct two outcome variables of interest: the amount of leisure time (in minutes) an individual spent on socializing with others (friends, parents, co-workers, neighbors) and the amount of individual leisure time spent on using the computer without the presence of others. While the ATUS does not elaborate on the precise activities the individual performed with a computer, the overall time allocated on this activity likely includes the time spent on using online dating sites, social networking sites, emailing, and chatting.Footnote 34 If Internet diffusion has indeed displaced traditional offline forms of search in favor of online alternatives, then we might also expect a decrease in the amount of time spent socializing with others likely accompanied by an increase in the time spent alone using a computer. In other words, if personal interaction (with friends, family, neighbors) declines in the Internet era, then the likelihood of meeting potential partners through ones’ offline social network may also diminish.

Table 7 (B and C) presents the results from the estimation of a model similar to Eq. 1 where the outcome variables are the amount of leisure time spent socializing with others and the amount of time spent alone on using a computer for nonwork-related purposes. The model is estimated using individual-level ATUS data for the survey years 2003–2006 on a sample of single (never married) respondents aged 21–30 years old. The estimates indicate that Internet availability is associated with significantly less time spent on interacting with others, which may imply a declining propensity to meet potential partners through traditional offline ways. On the other hand, time spent alone using a computer for leisure has significantly increased as a result of greater Internet availability. These effects do not only offer indirect support to the hypothesis that the Internet has likely reshaped the venues through which relationships are formed but also signify that this technology has profound and seemingly negative implications for social capital accumulation among young people and, in particular, of the type formed outside the household.Footnote 35

7 Conclusion

The Internet’s potential to change matching has been studied in the context of the labor and housing markets. The goal of this paper is to explore the impact of this technology on matching efficiency in the marriage market and, in particular, on the transition into first marriage. From a theoretical perspective, the Internet can be viewed as a mechanism that may reduce search frictions by increasing the arrival rate of offers or by reducing search costs. Since these mechanisms can affect the probability of marriage in different directions, the overall impact of Internet diffusion on marriage is theoretically a priori unclear. Therefore, determining the direction of this effect is ultimately an empirical question. To my knowledge, this is the first paper to empirically undertake this task.

To plausibly identify this effect, I exploit temporal and geographic variation in the diffusion of broadband Internet among households, which rapidly began to take place since the 1996 Telecommunications Act. I find that Internet expansion is associated with increased marriage rates in the benchmark population of 21–30-year-old whites. Similar effects are identified for younger individuals in the same racial group as well as for African-Americans. Whereas the available data do not allow determining which online search methods are effective, suggestive evidence is offered that the Internet has crowded out other traditional methods of meeting potential partners and that online dating services contribute to increased marriage rates.

While the analysis strongly suggests that Internet is a powerful technology with real effects on family formation, the quality of the matches formed through the Internet remains to be an open question. Although match quality may improve as the Internet allows for the selection of mates with desired characteristics, the easiness and the speed of meeting new divorcees make divorce an attractive option while increasing the likelihood of remarriage. In this context, I show that Internet availability improves the chances of being matched at all times (conditional on ever getting married) as opposed to be separated or divorced. However, I cannot disentangle whether this is due to the Internet leading to more stable matches or due to facilitating remarriage. Future research on this topic relying on better data will need to separately address these possibilities.

Notes

This was the first major amendment of the US telecommunications law since the Communications Act of 1934. Among the primary goals of the 1996 Act was the deregulation of the broadcasting market and the promotion of competition in the telecommunications industry by encouraging the entry of any communications business in the market. It was also the first time that the Internet was included in broadcasting and spectrum allotment.

Labor market outcomes that have been considered are unemployment duration, employer-to-employer flows, job search behavior, and the quality of employment matches. See Kuhn and Skuterund 2004; Kuhn and Mansour 2014; Fountain 2005; Stevenson, and Hadass 2004. For other outcomes, also see Brown and Goolsbee 481; Liebowitz and Zentner 2012; Goolsbee and Guryan 2006; and Kroft and Pope 2014.

Rosenfeld and Thomas 2012 conduct a descriptive sociological analysis of the ways the Internet has changed the market for romantic partners in the USA. His analysis is based on data from the How Couples Meet and Stay Together survey (HCMST). It is a nationally representative survey of 4,000 adults of whom almost 80 % are romantically linked to a spouse. Nontraditional, same-sex couples are oversampled. For a similar study covering Australia, the UK, and the USA, see Dutton et al. 2008.

There is an extensive literature linking early marriage for women to lower educational achievement and poverty (Klepinger et al. 1995; Dahl 2010) and early fertility to lower labor market earnings (Blackburn et al. 1993; Loughran and Zissimopoulos 2009). Goldin and Katz (2002) and Bailey (2006) also discuss how another technological phenomenon, oral contraception, affected labor force participation and the occupational choices of women in the 1970s via increases in the age at first marriage and age at first birth.

Median age at first marriage for women (men) was 23.9 (26.1) in 1990, 24.5 (26.9) in 1995, 25.1 (26.8) in 2000, and 25.3 (27.1) in 2005 (census estimates).

In a survey organized by Pew Internet (2005), more than 50 % of the Internet users agreed that misinformation regarding the true marital status is an important concern. Moreover, 20 % of those looking for a partner but who have never used online personals revealed that the lack of trust towards these sites is the main reason why they have not explored this venue. However, despite the fact that some stigma regarding online dating still persists, most Internet users do not view it simply as the last resort.

These arguments, essentially, also imply an ambiguous effect of the Internet on divorce and remarriage. If targeted search leads to matches of more compatible people, such matches will likely be more stable. However, if meeting people becomes easier at all times and ages so that a divorce seems less costly, then this could imply entering a marriage less thoughtfully to begin with. In the latter case, we might expect higher marriage rates (related to Internet expansion) but also higher incidence of divorce. I provide some preliminary suggestive evidence on the link between Internet diffusion and divorce in Section 5.5.

This figure is constructed as follows. Consider, for instance, the cohort aged 21 years old in 1980. This cohort will be 25 years old in 1984, 30 in 1989, 35 in 1994, and 40 in 1999. Hence, I calculate the fraction of ever married population aged (i) 21 in 1980, (ii) 25 in 1984, (iii) 30 in 1989, (iv) 35 in 1994, and (v) 40 in 1999 and then plot these five points on the graph.

(i) High-speed lines are defined as those that provide speeds exceeding 200 kbps in at least one direction. (ii) Prior to June 2005, providers with fewer than 250 high-speed lines in service in a particular state were not required to report data for that state. Small providers of high-speed connections are therefore underrepresented in the earlier data. This change in the filing requirement potentially introduces some measurement error in the measure of broadband diffusion, which likely attenuates my estimates. (iii) The FCC lumps, together in a single category, the high-speed lines that connect residential and small business end-user customers (as opposed to medium and large business, institutional or government end-user customers). A high-speed line is considered as being provided to an end user in the residential and small business category, if the customer orders a high-speed service of a type that is normally associated with residential customers. Unfortunately, there is no way to infer the share of these lines that are exclusively ordered by residential customers (as opposed to small businesses) and so the provided combined measure is the closest information available to household broadband adoption. This remains a limitation of the analysis and likely consists another potential source of measurement error. Henceforth, when the terms residential or home/household broadband/high-speed lines are used in the text to refer to the measure of broadband diffusion followed in this paper, it should be understood that this limitation has been applied. (iv) For confidentiality purposes, the FCC does not report the information on broadband deployment for Wyoming in 2000.

See Forman et al. (2012) for a similar strategy. The March CPS supplements provide annual information on the marital status of the respondents for all years since 1962.

It is worth noting that the broadband’s rate of diffusion has outpaced that of many other popular technologies in the past such as video cassette recorders and personal computers (NTIA 2004).

Most social networking and online dating sites such as Facebook, Google + , Classmates.com, eHarmony, and Yahoo Personals were lunched in the post-broadband era, that is, after 1996.

(i) An additional potential indicator of the surrounding economic environment, which can also influence the decision of marriage, is the evolution of house prices (Lehr et al. 2006). This variable is available from the census for only a subset of years of my baseline sample. For this reason, it is not part of the standard set of covariates used for model estimation. Controlling for this factor, however, in the subset of available sample years, essentially left the estimates unchanged. Furthermore, cellular telephony was another communication technology that began to diffuse before 1996 and which is likely complementary to broadband. This is because Internet connection can also be achieved through cell phones. FCC reports data on mobile phone subscribership by state in the years after 1998. Restricting the sample to the 2001–2006 period and controlling for cell phone adoption does not change the baseline estimates. Results are available upon request. (ii) To define high-tech industries, I follow Hecker (1999).

In an omitted analysis but available upon request, I supplemented the baseline specifications (Table 1) with an additional covariate, measuring the state’s household telephone penetration. The latter might be especially relevant as a potential proxy for the role of dial-up connection, which requires a telephone line. This control was not statistically significant in any specification and its inclusion did not modify any of the baseline estimates.

Individuals who cohabit as unmarried partners can only be identified in the data after 1995. Approximately 5 % of the individuals report living with an unmarried partner in the period 2001–2006. I treat individuals who cohabit as singles. However, the main findings remain intact if I treat them as married or if I eliminate them completely from my sample.

(i) Given the well-documented issues of linear probability models, I have also experimented with a probit specification. The coefficient of Internet diffusion was 0.0059 with a standard error of 0.002. (ii) Rates of 1.2–1.7 % result from 0.0052/0.435 and 0.0075/0.435, respectively, where 0.435 is the percentage of ever married white (non-Hispanic) population aged 21–30 years between 2001 and 2006. (iii) The unit of measurement of broadband diffusion is lines per 100 people in a state. To convert this to units of Internet usage, I proceed as follows. First, I use the 2000, 2001, and 2003 CPS Computer and Internet Use Supplements to construct an individual measure of home Internet usage. Then, I assign broadband penetration by state and survey year and regress Internet usage among 21–30-year-old (non-Hispanic) whites on broadband diffusion, basic individual covariates, state, year fixed effects, and state-specific time trends. The obtained coefficient is 0.012 and statistically significant. This implies that an expansion in household broadband by 1 line per 100 people increases home Internet usage in the focal demographic group by 1.2 percentage points. (iv) The instrumental variable (IV) coefficients are also very similar for men and women (0.013 and 0.01, respectively) and strongly statistically significant. Since both sides of the market are affected by Internet diffusion in very similar ways, in the remaining of the analysis, I pool the two samples together and study the combined effect.

(i) These effects generally remain in the model with state-specific linear time trends. The fraction of the population that is nonwhite as well as state GDP and household income become significant determinants of the decision of females (share nonwhite, GDP) and males (income), respectively, to marry in this extended model. (ii) As marriage and technology diffusion are dynamic processes, it is plausible that a given level of Internet penetration has lagged effects on the marriage response beyond the 3-month lag that is implied by the timing that the two variables are measured. To study the potential presence of such effects, I first use the Akaike criterion to select the model of distributed lags with the best fit. This amounts to estimating (1) with the contemporaneous level of Internet diffusion as well as its third and fifth lag. The estimated coefficients are 0.005 (s.e. 0.0018), -0.0016 (s.e. 0.0033), and 0.0092 (s.e. 0.0062), respectively. While the immediate effect remains almost identical to the coefficient estimated in the column 4 of Table 1, the lagged terms are not individually distinguishable from zero. The three coefficients are, however, jointly statistically significant. Moreover, note that the coefficient of the fifth lag is quantitatively larger than the contemporaneous estimate, implying nonnegligible long-term effects of Internet diffusion: an increase in Internet penetration by one additional line per 100 people in a given year will, all else constant, increase marriage rates by 0.9 percentage points 5 years later. Taking into account the lagged effects, over a 5-year period, a unit increase in Internet diffusion has a cumulative impact on marriage rates of 1.2 percentage points. This suggests an increase in marriage propensity by roughly 2.6 % from an overall mean of 0.484 during the entire period of study (0.012/0.484).

I have also experimented with models including up to a quartic state-specific time trend, with and without allowing for region-year interactions. The results are qualitatively robust and within the range of estimates displayed in Table 2.

As information on the state of residence in the previous year is not reported in 1995, conditioning on cross-state migration results in a small sample size reduction.

I have repeated this falsification test, experimenting with other temporal windows for the dependent variables. I did not find any systematic relationship between future diffusion and past outcomes in any of these cases. This falsification strategy is similar to that of Forman et al. (2012).

I focus on the age group of 25–35-year-old individuals when studying divorce response, because this is when first divorces likely take place. This specification also serves as a useful falsification check for the results presented in Section 5.5 concerning the impact of Internet adoption on other marital outcomes.

Residential telephone adoption is measured by the number of residential phones per family in a given state in 1955. I obtain information on the number of residential telephones in 1955 and the number of families from the 1956 County and City data book. In 1955, there were approximately 0.97 residential telephones per family. State adoption rates, however, varied from 0.40 (Mississippi) to 1.21 (New Jersey). No information is recorded for Alaska, which implies a small reduction in sample size when the IV specification is implemented.

In online Appendix Figs. 2 and 3 , I graph state broadband diffusion in 2005 against that predicted by the share of farm households in 1930 and the share of households in 1960 having hot- and/or cold-piped water (proxy for the presence of basic infrastructure). As expected, the states that adopted advanced telecommunication technologies in recent years are indeed those that had better infrastructure and a smaller share of the population residing in farms. The fact that such characteristics in 1930 and 1960 predict contemporaneous Internet diffusion provides further suggestive evidence in favor of the stability of these factors as determinants of technological diffusion over the course of the last 40 years.

(i) The IV estimates are robust to the exclusion of years 1990–1995 and to the inclusion of regional trends. I have also experimented with the share of farm households by state in 1930 and the share of households in a state having piped water in 1960 as alternative instruments. They are both strong predictors of household broadband adoption and produce very similar effects to the baseline instrument. (ii) The fact that the IV estimate is larger than the OLS is consistent with the presence of measurement error in the baseline regressions. Measurement error is a possibility since prior to 2005, the number of actual high-speed lines was likely underreported, given that smaller providers were not required to report to the FCC (see footnote 9).

One possible way to test the exclusion restriction of the instrument is to check whether telephone penetration in 1955 directly predicts marital patterns prior to the advent of broadband. Under the identifying assumption, the instrument should have no predictable power. Indeed, regressing marriage rates prior to broadband (1985–1995) on the instrument (interacted with year fixed effects) as well as state and year dummies, I find no significant effect between the two quantities.

(i) This is 0.0052* 14/0.548 and 0.013* 14/0.548, respectively, where 0.548 is the percentage of ever married white (non-Hispanic) population aged 21–30 years in 1990. (ii) In light of the calculations explained in footnote 17, an increase in residential broadband penetration by 14 lines per 100 people translates to a sizeable increase in home Internet usage by 17 percentage points. As people use broadband to access the Internet from other locations (such as at work), this is likely only a lower bound of the overall increase in Internet usage induced by broadband.

Table 5 shows OLS and IV estimates in order to provide a lower and an upper bound of the effect.

The March CPS does not formally distinguish between urban and less urban areas. Hence, I define an area as urban on the basis of the metropolitan status of the respondent. I categorize the individual as residing in an urban area if he/she reports living in the central city of a metropolitan statistical area (MSA). If instead a broader definition is chosen whereby urban reflects whether an individual resides in a metro area, then the results clearly indicate that the baseline effects are driven by respondents living in MSAs.

Using the 2005 Pew Internet and American Life Project Survey, I find that conditional on being an Internet user, young African-Americans are as likely as whites to use online personals. This observation pertains to other survey years as well and is also reflective of the fact that, while racial digital divide still persists, the share of African-Americans that are Internet users increased dramatically between 2000 and 2011, especially when compared to other racial groups. The share of Black (non-Hispanic) adults using the Internet increased from 35 % in June 2000 to 71 % in August 2011. For whites (non-Hispanic), the change was relatively more modest climbing from 49 to 80 % within the same period. For Hispanics, Internet usage increased from 40 to 68 % (Pew Internet and American Life Project report; Zickuhr and Smith 2012).