Abstract

Purpose

Past suicide attempts (SA) are a major contributor to suicide. The prevalence of SA in pregnant and postpartum women varied significantly across studies. Therefore, this meta-analysis was conducted to examine the prevalence of SA and its mediating factors in this population.

Methods

Relevant articles published in PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, PsycINFO, Medline complete, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure database (CNKI), Chinese Wanfang and Chongqing VIP database were systematically searched from inception to March 28, 2019. Titles, abstracts and full texts were reviewed independently by three researchers. Studies were included if they reported data on SA prevalence or provided relevant data that enabled the calculation of SA prevalence. Data were extracted by two researchers and checked by one senior researcher. The random-effects model was used to analyze data by the CMA 2.0 and Stata 12.0, with the high degree of statistical heterogeneity present. The primary outcomes were prevalence of SA with 95% CI during pregnancy and during the first-year postpartum.

Results

Fourteen studies covering 6,406,245 pregnant and postpartum women were included. The pooled prevalence of SA was 680 per 100,000 (95% confidence interval 0.10–4.69%) during pregnancy and 210 per 100,000 (95% confidence interval 0.01–3.21%) during the first-year postpartum. Data source was significantly associated with prevalence of SA in the subgroup analysis (pregnancy, p < 0.001; the first-year postpartum, p = 0.013).

Conclusion

The prevalence of SA is not high in pregnant and postpartum women. Due to the potential loss of life and negative impact of SA on health outcomes, however, careful screening and effective preventive measures should be implemented for this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Suicide is a major global public health challenge [1, 2]. Approximately, 800,000 individuals (annual rate of 10.6 per 100,000 population) die from suicide annually, with a suicide rate of 13.5 per 100,000 population in men and 7.7 per 100,000 population in women [3]. Persons with a past suicide attempt (SA) [4] usually have 20–30 times higher risk of future completed suicide than those without [5]. The global annual prevalence of self-reported SA is approximately 0.3% [6, 7]. Apart from increased likelihood of completed suicide, SA is highly associated with other negative outcomes, such as physical injuries, hospitalization, and increased treatment burden [8, 9]. For instance, a study found that global rate of years of life lost (YLL) associated with suicidality was 458.4 (438.5–506.1) per 100 000, accounting for 2.18% (1.9–2.2%) of total YLL [10]. Another study in Switzerland found that the extrapolated direct medical cost for medical treatment of SA per year amounted to 191 million Swiss Francs (CHF) [11].

Pregnant and postpartum women with SA also have various negative outcomes; for example, suicidality was associated with 2.2–13% of maternal deaths [12,13,14,15], greater risk of premature labor and caesarean delivery, and increased need for blood transfusion [16, 17]. To allocate health resources, develop relevant policies, implement effective preventive measures and treatment, and reduce poor SA-related health outcomes of in pregnant and postpartum women, better understanding of SA patterns is important. In the past years, a range of studies have examined the prevalence of SA and its correlates among pregnant and postpartum women, with mixed findings. For instance, one study found that the prevalence of SA was 40 per 100,000 pregnant women and risk factors included premature labor, cesarean delivery, and need for blood transfusion [18], while another study found that the prevalence of SA was 5190 per 100,000 pregnant women and risk factors included anxiety/depression, and experience of verbal or physical/sexual abuse [19]. In contrast, a study found that prevalence of SA was 10 per 100,000 postpartum women and risk factors included single, widowed or divorced marital status, history of a caesarean delivery or suicidality, and postpartum depression [20].

To date, no meta-analysis or systematic review synthesized the prevalence and correlates of SA; thus, we conducted this meta-analysis to examine the prevalence and moderating factors (e.g., study design and sites, sample size and mean age) of SA in pregnant and postpartum women. Based on previous findings that pregnant and postpartum depression was common [21,22,23,24] and the association between depression and suicidality [25, 26], we hypothesized that SA in pregnant and postpartum women would be common.

Methods

Data sources and search strategies

The study protocol has been reviewed in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO: CRD42020188798). This meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline. A systematic review of relevant publications in PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, PsycINFO, Medline complete, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure database (CNKI), Chinese Wanfang and Chongqing VIP database was independently searched by three researchers (WWR, YY and TJM) from the inception dates of the target databases up to March 28, 2019. The following search terms were used: attempted suicide, suicide attempt, suicide attempt*, parasuicide*, suicide*, self-injurious behavior, postpartum, perinatal, antenatal, mother, mom, maternal, wife, pregnant women.

Study eligibility

Titles and abstracts of relevant publications were screened, and then the full texts were read independently by the same three researchers. Any disagreements were resolved by a discussion and consensus, with final arbitration by with a senior researcher (YTX) if necessary. Studies were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: (a) SA occurred during pregnancy or the first-year postpartum; (b) cross-sectional or cohort studies; (c) studies reporting prevalence of SA or providing relevant data that enabled the calculation of prevalence of SA. Case reports, study protocols, editorials, systematic reviews and those conducted in special populations [such as those with mental disorders or major medical conditions, or health professionals] were excluded.

Data extraction

Data of study and participant characteristics were independently extracted by two researchers (YY and TJM). Any disagreements were resolved by a discussion, consensus, or consulting another researcher (WWR). Study (publication year and language, country, continent, study design, initial sample size, actual sample size, attrition rate, study site, source of data, and year of survey) and participant characteristics (period, time, mean age and standard deviation, age range and primipara), and suicide attempt-related data (i.e., frequency) were extracted.

Quality assessment

Study quality was assessed using the Parker’s quality evaluation tool for prevalence studies [27], which has been widely used [28,29,30]. The tool contains six items, including definition and representativeness of targeted population, sampling methods, response rate, definition of the target symptom or diagnosis and validation of the assessment instrument. Each item was rated as “1 (yes)” or “0 (no or unclear)”. The total score ranges from 1 to 6 with a higher score indicating better quality [31]. All studies were independently assessed by two researchers (YY and TJM).

Statistical analyses

Prevalence of SA with 95% CI was calculated using the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model with Natural Log transformation. Heterogeneity was examined using the Q and I2 statistic, and significant heterogeneity was defined as p value ≤ 0.05 in the Q test and I2 > 50%. Publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of the funnel plots, Begg’s and Egger’s tests. The “metatrim” command with the linear trimming estimator was performed in trim and fill adjusted analysis [32]. Subgroup analyses were performed to examine the moderating associations between SA prevalence and the following categorical variables: publication language (English or Chinese), type of study site (hospital, community, or mixed), study design (cross-sectional or longitudinal), and continent (i.e., Asia, America, Europe or Africa). The associations between prevalence of SA and continuous variables including year of publication, survey year based on end year, sample size, age and study quality were analyzed by meta-regression analyses [33]. Sensitivity analyses were used to examine the robustness of the primary results by excluding the included studies one by one. STATA, Version 12.0 for Windows (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA) and CMA, Version 2 (Biostat Inc., Englewood, New Jersey, USA). Significance level was set at 0.05 (two-sided).

Results

Study selection and characteristics

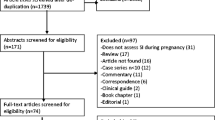

In the literature search, 1464 relevant studies were identified; of them, 420 were excluded due to duplicates, 955 were excluded by screening titles and abstracts, then 75 were excluded by reviewing the full texts. Finally, 14 studies with 6,406,245 participants were included. The procedure of study selection is summarized in Fig. 1. One study provided data of SA in both antenatal and postnatal women; therefore, the data were extracted and analyzed in two separate groups [34]. Study and participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. The included studies (antenatal: n = 8; postnatal: n = 5; antenatal and postnatal: n = 1) were published between 2006 and 2019, with the sample size ranging from 32 to 4,833,286. Five studies were conducted in Asia, two in Europe, two in Africa, four in North America, and one in South America. Two studies were longitudinal [34, 35], while the remaining were cross-sectional.

Quality assessment, publication bias and sensitivity analysis

Table S1 shows that quality assessment scores of the 14 studies, ranging from 3 to 6, with the median of 4. The funnel plot was symmetrical, and Egger’s and Begg’s tests did not suggest publication bias [antenatal: (Egger: t = 2.21, p = 0.063; Begg: Z = − 0.63, p = 0.532); postnatal: (Egger: t = 0.87, p = 0.435; Begg: Z = − 0.19, P = 0.851); Fig. 2]. The Duval and Tweedies’s trim and fill analysis did not reveal any missing studies, which indicates that no missing effect size qualitatively affected the pooled results. Sensitivity analyses did not find individual study which could significantly change the robustness of the primary results.

Prevalence of suicide attempt, subgroup and meta-regression analyses

During pregnancy, the pooled prevalence of SA was 680 per 100,000 (n = 4,883,231; 95% CI 0.10–4.69%; I2 = 99.6%; Fig. 3). During the first year of postpartum, the pooled prevalence of SA was 210 per 100,000 (n = 1,568,376; 95% CI 0.01–3.21%; I2 = 99.5%; Fig. 3). Subgroup analyses found that data collected in field surveys were associated with higher prevalence of SA in both pregnancy and the first year of postpartum (both p < 0.05), while other study characteristics were not associated with prevalence of SA (Table 2). The prevalence estimates of SA by study site and continent are presented in Figures S1 and S2. Meta-regression analysis did not find any study characteristics significantly associated with prevalence of SA (p values > 0.05, Table 2).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first meta-analysis to examine the worldwide prevalence of SA in pregnant and postpartum women. The prevalence of SA was 680 per 100,000 (95% CI 0.10–4.69%) within the pregnancy period and 210 per 100,000 (95% CI 0.01–3.21%) within the first postpartum year. The SA during prenatal and postpartum period could be due to several reasons. First, prenatal and postpartum depression is common [36, 37], which is a major risk factor for suicide-related behaviours including SA [38]. Second, prenatal and postpartum women often experience psychological symptoms related to suicide-related behaviours, such as premenstrual irritability, perceived pregnancy complications, negative attitude toward pregnancy, anxiety about birth, and social withdrawal [35, 39, 40]. Third, some studies [41, 42] found that certain delivery methods, such as caesarean delivery, were associated with increased SA risk [20] among women who are introverted and have high emotionality [43] and lower self-efficacy [44]. Fourth, intimate partner violence, including verbal abuse, physical and/or sexual violence, is associated with increased risk of SA during pregnancy [19].

To date, no meta-analysis on SA among pregnant and postpartum women was published; therefore, we cannot directly compare our findings with estimates from previous studies. We chose to examine differences between our study estimates and those derived from studies of one-year prevalence of SA in other populations. Prevalence of SA in this meta-analysis is similar to the one-year prevalence of SA in the female general population in some studies, e.g., the figure was 300 per 100,000 in high-income countries and 500 per 100,000 in low- and middle-income countries [7]. However, our result is lower than the figures in college female students worldwide (1260 per 100,000, 95% CI 0.82–1.8%) [45] and in Korean female adolescents (6300 per 100,000) [46]. It should be noted that different population characteristics and prevalence timeframe (e.g., during pregnancy and the postpartum period vs. 1 year) hinder direct comparisons between studies. The prevalence of SA in this study was not as high as we hypothesized, which probably may be due to the following reason. Depression is a major contributor of SA [47, 48]. However, most previous studies reporting common pregnant and postpartum depression only focused on mild-moderate depressive symptoms as measured by screening scales [49, 50], rather than the clinical diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD). Mild-moderate depressive symptoms may be more likely to increase the risk of suicidal ideation and suicide plan, rather than severe suicidality, such as SA and suicide in clinical practice. As expected, a positive association between data collected in field surveys and the prevalence of SA was found. Data scrutinized from databases were often underestimated because some useful information could not be recorded due to lack of face-to-face interviews and use of standardized instruments which were often used in field surveys.

Strengths of this study include the large sample size and use of sophisticated data analyses (e.g., subgroup and meta-regression analyses, and sensitivity analysis). However, some limitations should be noted in this meta-analysis. First, only articles in English and the Chinese languages were included, thus, those published in other languages may be missed. Second, similar to other meta-analyses of epidemiological studies on suicidality [4, 51], high heterogeneity still remained, even though subgroup analyses were performed. The source of heterogeneity may be related to certain unreported factors, such as pregnancy care, way of delivery, and family relationships. Third, some variables related to SA, such as economic status, information of prior SA in people who died of suicide, history of psychiatric disorders, substance use [8, 52], were not analyzed due to insufficient data reported by included studies. Fourth, the large difference in sample size between studies was mainly due to different source of data (e.g., secondary analyses of databases vs. survey-based samples). However, no moderating effect of the sample size on the results was found in subgroup analyses. In addition, sensitivity analyses did not find outlying studies with large or small sample size that could significantly affect the primary results. Fifth, some studies included in this meta-analysis had lower scores in quality assessment, which might bias the results. Sixth, fatal SAs were not recorded in included studies, which might bias the results. Seventh, due to the relatively low prevalence of SA and/or small sample size in some studies, the confidence intervals were large in the forest plot. Finally, most studies were conducted in Asia and North America, which limits the generalizability of the findings.

In summary, this meta-analysis found that SA is not high in pregnant and postpartum women compared to 1-year prevalence of SA in other populations. Considering the negative impact of SA on health outcomes and potential loss of life, hence clinicians should routinely screen SA in pregnant and postpartum women and undertake effective treatments if necessary, such as public education on suicide prevention and providing hotline services. Appropriate psychotropic treatments should be prescribed for those with severe psychiatric symptoms. Prospective studies on the association between SA and other demographic and clinical variables in pregnant and postpartum women are warranted in the future. In addition, international studies could be conducted to explore the impact of different sociocultural and economic factors on suicide attempt in this population.

References

Turecki G, Brent DA (2016) Suicide and suicidal behaviour. Lancet 387(10024):1227–1239. https://doi.org/10.1016/0140-6736(15)00234-2

Cheung VH, Chan CY, Au RK (2019) The influence of resilience and coping strategies on suicidal ideation among Chinese undergraduate freshmen in Hong Kong. Asia-Pacif Psychiatry 11(2):e12339. https://doi.org/10.1111/appy.12339

World Health Statistics 2019: Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. World Health Organization. 2019 [Novmber 27, 2019]. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/324835/9789241565707-eng.pdf

Dong M, Zeng L-N, Lu L, Li X-H, Ungvari GS, Ng CH, Chow IH, Zhang L, Zhou Y, Xiang Y-T (2019) Prevalence of suicide attempt in individuals with major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of observational surveys. Psychol Med 49(10):1691–1704. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718002301

Zalsman G, Hawton K, Wasserman D, van Heeringen K, Arensman E, Sarchiapone M, Carli V, Höschl C, Barzilay R, Balazs J, Purebl G, Kahn JP, Sáiz PA, Lipsicas CB, Bobes J, Cozman D, Hegerl U, Zohar J (2016) Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry 3(7):646–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(16)30030-x

Bilsen J (2018) Suicide and youth: risk factors. Front Psychiatry 9:540. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00540

Borges G, Nock MK, Haro Abad JM, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Alonso J, Andrade LH, Angermeyer MC, Beautrais A, Bromet E, Bruffaerts R, de Girolamo G, Florescu S, Gureje O, Hu C, Karam EG, Kovess-Masfety V, Lee S, Levinson D, Medina-Mora ME, Ormel J, Posada-Villa J, Sagar R, Tomov T, Uda H, Williams DR, Kessler RC (2010) Twelve-month prevalence of and risk factors for suicide attempts in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. J Clin Psychiatry 71(12):1617–1628. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.08m04967blu

Klonsky ED, May AM, Saffer BY (2016) Suicide, suicide attempts, and suicidal ideation. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 12:307–330. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093204

Pengpid S, Peltzer K (2020) Past 12-month history of single and multiple suicide attempts among a national sample of school-going adolescents in Tonga. Asia-Pacif Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1111/appy.12425

Naghavi M (2019) Global, regional, and national burden of suicide mortality 1990 to 2016: systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. BMJ 364:l94. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l94

Czernin S, Vogel M, Flückiger M, Muheim F, Bourgnon J-C, Reichelt M, Eichhorn M, Riecher-Rössler A, Stoppe G (2012) Cost of attempted suicide: a retrospective study of extent and associated factors. Swiss Med Weekly 142:w13648. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2012.13648

Syverson CJ, Chavkin W, Atrash HK, Rochat RW, Sharp ES, King GE (1991) Pregnancy-related mortality in New York City, 1980 to 1984: Causes of death and associated risk factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol 164(2):603–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9378(11)80031-1

Dannenberg AL, Carter DM, Lawson HW, Ashton DM, Dorfman SF, Graham EH (1995) Homicide and other injuries as causes of maternal death in New York City, 1987 through 1991. Am J Obstet Gynecol 172(5):1557–1564. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(95)90496-4

Lindahl V, Pearson JL, Colpe L (2005) Prevalence of suicidality during pregnancy and the postpartum. Arch Women’s Mental Health 8(2):77–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-005-0080-1

Fildes J, Reed L, Jones N, Martin M, Barrett J (1992) Trauma: the leading cause of maternal death. J Trauma 32(5):643–645

Högberg U, Innala E, Sandström A (1994) Maternal mortality in Sweden, 1980–1988. Obstet Gynecol 84(2):240–244

Gentile S (2011) Suicidal mothers. J Injury Violence Res 3(2):90–97. https://doi.org/10.5249/jivr.v3i2.98

Gandhi SG, Gilbert WM, McElvy SS, El Kady D, Danielson B, Xing G, Smith LH (2006) Maternal and neonatal outcomes after attempted suicide. Obstet Gynecol 107(5):984–990. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000216000.50202.f6

Asad N, Karmaliani R, Sullaiman N, Bann CM, McClure EM, Pasha O, Wright LL, Goldenberg RL (2010) Prevalence of suicidal thoughts and attempts among pregnant Pakistani women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 89(12):1545–1551. https://doi.org/10.3109/00016349.2010.526185

Weng SC, Chang JC, Yeh MK, Wang SM, Chen YH (2016) Factors influencing attempted and completed suicide in postnatal women: a population-based study in Taiwan. Sci Rep 6:25770. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep25770

Cameron EE, Sedov ID, Tomfohr-Madsen LM (2016) Prevalence of paternal depression in pregnancy and the postpartum: an updated meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 206:189–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.07.044

Learman LA (2018) Screening for depression in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Clin Obstet Gynecol 61(3):525–532. https://doi.org/10.1097/GRF.0000000000000359

Tebeka S, Le Strat Y, Dubertret C (2016) Developmental trajectories of pregnant and postpartum depression in an epidemiologic survey. J Affect Disord 203:62–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.058

Kazemi A, Dadkhah A (2020) Changes in prenatal depression and anxiety levels in low risk pregnancy among Iranian women: a prospective study. Asia-Pacif Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1111/appy.12419

Teismann T, Forkmann T, Brailovskaia J, Siegmann P, Glaesmer H, Margraf J (2018) Positive mental health moderates the association between depression and suicide ideation: a longitudinal study. Int J Clin Health Psychol 18(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2017.08.001

Zhao S, Zhang J (2018) The association between depression, suicidal ideation and psychological strains in college students: a cross-national study. Cult Med Psychiatry 42(4):914–928. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-018-9591-x

Parker G, Beresford B, Clarke S, Gridley K, Pitman R, Spiers G, Light K (2008) Technical report for SCIE research review on the prevalence and incidence of parental mental health problems and the detection, screening and reporting of parental mental health problems. Social Policy Research Unit, University of York, York

Yang Y, Li W, Ma T-J, Zhang L, Hall BJ, Ungvari GS, Xiang Y-T (2020) Prevalence of poor sleep quality in perinatal and postnatal women: a comprehensive meta-analysis of observational studies. Front Psychiatry 11:Article 161. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00161

Yang Y, Li W, Lok K-I, Zhang Q, Hong L, Ungvari GS, Bressington DT, Cheung T, Xiang Y-T (2020) Voluntary admissions for patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian J Psychiatry 48:101902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2019.101902

Li W, Yang Y, Hong L, An F-R, Ungvari GS, Ng CH, Xiang Y-T (2019) Prevalence of aggression in patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Asian J Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2019.101846

Zeng L-N, Yang Y, Feng Y, Cui X, Wang R, Hall BJ, Ungvari GS, Chen L, Xiang Y-T (2019) The prevalence of depression in menopausal women in China: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Affect Disord 256:337–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.06.017

Duval S, Tweedie R (2000) Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 56(2):455–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x

Knapp G, Hartung J (2003) Improved tests for a random effects meta-regression with a single covariate. Stat Med 22(17):2693–2710. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1482

Mota NP, Chartier M, Ekuma O, Nie Y, Hensel JM, MacWilliam L, McDougall C, Vigod S, Bolton JM (2019) Mental disorders and suicide attempts in the pregnancy and postpartum periods compared with non-pregnancy: a population-based study. Can J Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743719838784

Newport DJ, Levey LC, Pennell PB, Ragan K, Stowe ZN (2007) Suicidal ideation in pregnancy: assessment and clinical implications. Arch Women’s Mental Health 10(5):181–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-007-0192-x

Sheeba B, Nath A, Metgud CS, Krishna M, Venkatesh S, Vindhya J, Murthy GVS (2019) Prenatal depression and its associated risk factors among pregnant women in Bangalore: a hospital based prevalence study. Front Public Health 7:108–108. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00108

Anokye R, Acheampong E, Budu-Ainooson A, Obeng EI, Akwasi AG (2018) Prevalence of postpartum depression and interventions utilized for its management. Ann Gen Psychiatry 17:18–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-018-0188-0

Hawton K, Casañas i Comabella C, Haw C, Saunders K, (2013) Risk factors for suicide in individuals with depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 147(1):17–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.004

Kim JJ, La Porte LM, Saleh MP, Allweiss S, Adams MG, Zhou Y, Silver RK (2015) Suicide risk among perinatal women who report thoughts of self-harm on depression screens. Obstet Gynecol 125(4):885–893. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000000718

Orsolini L, Valchera A, Vecchiotti R, Tomasetti C, Iasevoli F, Fornaro M, De Berardis D, Perna G, Pompili M, Bellantuono C (2016) Suicide during perinatal period: epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical correlates. Front Psychiatry 7:138–138. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00138

Feng J, Li S, Chen H (2015) Impacts of stress, self-efficacy, and optimism on suicide ideation among rehabilitation patients with acute pesticide poisoning. PLoS ONE 10(2):e0118011. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118011

DeShong HL, Tucker RP, O’Keefe VM, Mullins-Sweatt SN, Wingate LR (2015) Five factor model traits as a predictor of suicide ideation and interpersonal suicide risk in a college sample. Psychiatry Res 226(1):217–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.01.002

Johnston RG, Brown AE (2013) Maternal trait personality and childbirth: the role of extraversion and neuroticism. Midwifery 29(11):1244–1250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2012.08.005

Ji H, Jiang H, Yang L, Qian X, Tang S (2015) Factors contributing to the rapid rise of caesarean section: a prospective study of primiparous Chinese women in Shanghai. BMJ Open 5(11):e008994. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008994

Mortier P, Cuijpers P, Kiekens G, Auerbach R, Demyttenaere K, Green J, Kessler R, Nock M, Bruffaerts R (2018) The prevalence of suicidal thoughts and behaviours among college students: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med 48(4):554–565. https://doi.org/10.1017/0033291717002215

Kang E-H, Hyun MK, Choi SM, Kim J-M, Kim G-M, Woo J-M (2015) Twelve-month prevalence and predictors of self-reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempt among Korean adolescents in a web-based nationwide survey. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 49(1):47–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867414540752

Cavanagh JT, Carson AJ, Sharpe M, Lawrie SM (2003) Psychological autopsy studies of suicide: a systematic review. Psychol Med 33(3):395–405. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291702006943

Roca M, del Amo AR-L, Riera-Serra P, Pérez-Ara MA, Castro A, Roman Juan J, García-Toro M, García-Pazo P, Gili M (2019) Suicidal risk and executive functions in major depressive disorder: a study protocol. BMC Psychiatry 19(1):253. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2233-1

Sunnqvist C, Sjöström K, Finnbogadóttir H (2019) Depressive symptoms during pregnancy and postpartum in women and use of antidepressant treatment–a longitudinal cohort study. Int J Women’s Health 11:109. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S185930

Sahin E, Seven M (2018) Depressive symptoms during pregnancy and postpartum: a prospective cohort study. Perspect Psychiatric Care 55(3):430–437. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12334

Lu L, Dong M, Zhang L, Zhu X-M, Ungvari GS, Ng CH, Wang G, Xiang Y-T (2019) Prevalence of suicide attempts in individuals with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Epidemiol Psychiatric Sci. https://doi.org/10.1017/2045796019000313

Jung M (2019) The relationship between alcohol abuse and suicide risk according to smoking status: a cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord 244:164–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.09.077

Girardi P, Pompili M, Innamorati M, Serafini G, Berrettoni C, Angeletti G, Koukopoulos A, Tatarelli R, Lester D, Roselli D, Primiero FM (2011) Temperament, post-partum depression, hopelessness, and suicide risk among women soon after delivering. Women Health 51(5):511–524. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2011.583980

Onah MN, Field S, Bantjes J, Honikman S (2017) Perinatal suicidal ideation and behaviour: psychiatry and adversity. Arch Women’s Mental Health 20(2):321–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-016-0706-5

Paris R, Bolton RE, Weinberg MK (2009) Postpartum depression, suicidality, and mother-infant interactions. Arch Women’s Mental Health 12(5):309–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-009-0105-2

Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, Romito P, Lelong N (2007) Women’s psychological health according to their maternal status: a study in France. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 28(4):243–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/01674820701350351

Su PY, Hao JH, Tao FB (2010) Adverse psychology and behaviors in pregnant women with different types of behavior (in Chinese). Chin Mental Health J 24(12):908–911. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2010.12.006

Xie QR, Cheng GY, Wang QF, Sun ZT, Cheng ZP (2010) A study on relationship between adverse psychology, behavior and alexithymia among prenant women (in Chinese). Chin J Woman Child Health Res 21(6):747–749. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1673-5293.2010.06.012

Shamu S, Zarowsky C, Roelens K, Temmerman M, Abrahams N (2016) High-frequency intimate partner violence during pregnancy, postnatal depression and suicidal tendencies in Harare, Zimbabwe. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 38:109–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.10.005

Supraja TA, Thennarasu K, Satyanarayana VA, Seena TK, Desai G, Jangam KV, Chandra PS (2016) Suicidality in early pregnancy among antepartum mothers in urban India. Arch Women’s Mental Health 19(6):1101–1108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-016-0660-2

Vergel J, Gaviria SL, Duque M, Restrepo D, Rondon M, Colonia A (2019) Gestation-related psychosocial factors in women from Medellin, Colombia. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatria 48(1):26–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcp.2017.06.003

Yang XL (2007) Evaluation of psychological status and corresponding nursing of psychological disorder among parturient women (in Chinese). J Qiqihar Med Coll 28(5):601–602. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-1256.2007.05.052

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the University of Macau (MYRG2019-00066-FHS), the National Key Research & Development Program of China (No. 2016YFC1307200), the Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Incubating Program (No. PX2016028) and the Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals’ Ascent Plan (No. DFL20151801).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest related to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rao, WW., Yang, Y., Ma, TJ. et al. Worldwide prevalence of suicide attempt in pregnant and postpartum women: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 56, 711–720 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01975-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01975-w