Abstract

Purpose

We investigated if (a) people with lower physical activity have an increased risk of subsequent mental disorders (compared to those with higher physical activity); and (b) people with mental disorders have reduced subsequent physical activity (compared to those without mental disorders).

Methods

A systematic review of population-based longitudinal studies examining physical activity and mental disorders was conducted. Mental disorders were defined by International Classification of Diseases or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. The results were described in a narrative summary.

Results

Twenty-two studies were included. The majority (19) examined mood disorders and physical activity. Only two studies found consistent association between lower physical activity and a reduced risk of subsequent mental disorders. One study found the bidirectional association between physical activity and major depression. Twelve studies found mixed results (i.e., no consistency in direction and significance of the findings), and seven studies found no association between the variables of interest.

Conclusions

There is a lack of consistent evidence linking physical activity to be either a risk factor or consequence of mental disorders.

PROSPERO registration ID

CRD42017071737.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background and significance

People with mental disorders are at an increased risk of physical comorbidity [1, 2] and associated differential mortality [3, 4]. Compared to the general population, people with mental disorders engage in significantly less physical activity (PA) [5, 6]. PA interventions have demonstrated benefits in both psychological and physical well-beings of people with mental disorders [7, 8]. While much of the existing evidence for the efficacy of PA among people with mental disorders consists of findings from randomized-controlled trials [9], they are often limited by factors such as selection bias (e.g., participants who completed the study are more likely to be motivated to be physically active than non-participants) and short-study duration. Cohort studies can mitigate some of these limitations and may facilitate examination of the “real world effectiveness” of PA. To date, reviews examining the association between mental disorders and PA have been limited to people with depression. Mammen and Faulkner [10] found that 25 out of 30 longitudinal studies identified demonstrated that increased PA was associated with a reduced risk of subsequent depression. Roshanaei-Moghaddam and colleagues [11], on the other hand, examined the effect of baseline depression on subsequent PA. Eight out of eleven studies included found that depression at baseline was associated with subsequent reduction in PA. More recently, a comprehensive systematic review by Schuch et al. examined 49 longitudinal studies consisting of 266,935 participants to find that those with high levels of PA had lower odds of developing depression (odds ratio (OR) 0.83; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.79–0.88) [12]. It should be noted that previous reviews were based on a broad range of measures of depression—some were symptom scales and others diagnostic instruments. This has implications for clinical interpretation of the findings and casts doubt on the validity of pooling such widely disparate measures of depression [10]. Thus, this systematic review examines the following research questions: (1) Do people with lower PA have an increased risk of subsequent mental disorders—including mood disorders, anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, and psychotic disorders—compared to those with higher PA?, and: (2) Do people with mental disorders have reduced subsequent PA compared to those without mental disorders? It was hypothesized that: (1) people with lower PA would have an increased risk of subsequent mental disorders compared to those with higher PA, and (2) people with mental disorders would have reduced subsequent PA. To optimize the clinical utility of the analyses, this review focused on traditional diagnostic criteria for mental disorders.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline [13] and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guideline [14]. This study was prospectively registered in advance with PROSPERO (registration ID CRD42017071737). The following databases were searched for English-language, original research articles published in peer-review journals from inception to September 2017 initially, and then updated in May 2019: Medline, PubMed, EMBASE, PsychInfo, CINAHL, and Web of Science. In addition, references from articles identified as well as several systematic reviews [10, 11, 15,16,17,18,19,20,21] in the field were examined to identify any other article eligible. The following search algorithm was used: (“exercise” OR “physical activity”) AND (“schizophrenia” OR “psychosis” OR “depression” OR “bipolar” OR “serious mental illness” OR “severe mental illness” OR “anxiety” OR “substance use disorder” OR “substance dependence” OR “alcohol use disorder” OR “alcohol dependence” OR “stimulant use disorder” OR “stimulant dependence” OR “common mental illness” OR “common mental disorder”) AND (“longitudinal” OR “observational”). The inclusion criteria of the current review were: (a) longitudinal observational study with either prospective or retrospective design of at least 12 months of follow-up; (b) study populations include people with mental disorders (defined as those who meet the diagnostic criteria, either International Classification of Diseases (ICD, any version) or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM, any version) for mood disorders, anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, and psychotic disorders) as well as people without mental disorders of interest (“the general population”); (c) presence of mental disorder diagnoses or self-reported or objectively measured PA at the study baseline; and (d) outcome measures of either; change in PA over time in those with mental disorders compared to the general population, or incidence of mental disorders.

Data extraction

Titles and abstracts of the articles were reviewed to identify studies that met the eligibility criteria. Eligibility assessment was then performed by two authors (SS and BS) independently. In keeping with previous reviews [5, 22], the following characteristics were extracted from each study when available: (a) study description (including author, publication year, location, study design, follow-up period, sample numbers, loss to follow-up, age, gender, PA measures, and mental disorder measures), and (b) study findings (effect size metrics, 95% CI, and confounders adjusted for). The study findings were examined and summarized according to consistency in direction and significance of the results. Two independent researchers extracted the data (SS and BS) and disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Methodological quality appraisal

The assessment of risk of bias in each study was evaluated using Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) [23] (Supplementary Table 1). Points are assigned based on the selection process of cohorts (0–4 points), the comparability of the cohorts (0–2 points), and the identification of the exposures and the outcomes of research participants (0–3 points). Two reviewers (SS and BS) independently assessed the methodological quality of each study with disagreements resolved by discussion.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to present a summary of the findings. As studies included were not sufficiently homogeneous in terms of exposure, comparator, and outcomes, meta-analysis of studies was not conducted in the current review.

Results

The search of Medline, PubMed, EMBASE, PsychINFO, CINAHL, and Web of Science databases identified a total of 8407 potential papers (Fig. 1). After removing duplicates, 4665 papers remained. Additional five papers were located through reference lists from other systematic reviews on the topic. Of these 4670 papers, 4647 papers were discarded after reviewing the titles and abstracts. The full texts of remaining 23 papers were examined. Six papers required further discussion before consensus was reached. Three corresponding authors were contacted via email for further data and/or clarification. All three authors [24,25,26] responded to our correspondence and two [24, 25] provided us with further data. A total of 18 studies were identified for inclusion initially. The updated search was conducted in May 2019. Additional 2672 potential non-duplicated papers were identified. After discarding 1153 duplicates, 1519 papers remained. The full texts of eight papers were examined after reviewing the titles and abstracts. Four additional papers were identified for inclusion. Therefore, a total of 22 studies were identified for inclusion in the review.

Study characteristics

A summary of included studies is presented in Table 1. Of 22 studies included, four studies examined the association between baseline mental disorders and subsequent PA [25, 27,28,29], and only one study [30] reported on the bidirectional relationship between the variables of interest. The other 17 studies examined the association between baseline PA and subsequent mental disorders. The number of participants ranged from 496 [30] to 25,520 [31] and follow-up periods ranged from 15 months [24] to 26 years [32].

The majority of the included studies (13 out of 18) examined depressive disorders [27, 28, 30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40], while one examined both depressive disorders and anxiety disorders [25] and another [41] examined mood disorders in general. One study [42] examined anxiety disorders only. Two studies examined the relationship between PA and alcohol use disorder [24, 43]. Three studies assessed mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and substance use disorders within the same samples [29, 44, 45]. One study [46] examined mood disorders, anxiety disorders, substance use disorders as well as psychotic disorders within the same cohort group. The majority of the studies (16 out of 22) utilized DSM criterion [24, 25, 27,28,29,30, 34,35,36,37,38, 40, 42, 44,45,46], while five used ICD criterion [31,32,33, 41, 43]. One study did not specify the diagnostic criteria used, but was included, because the study utilized Composited International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) questionnaire to derive its diagnoses [39].

In contrast to mental disorder diagnoses, there was little consistency in how PA was measured and categorized. None of the included studies used objective PA measurement tools. Eight studies used validated questionnaires like IPAQ [47], with remaining 14 studies relying on isolated self-reported PA items, often from just one question (e.g. “Over the past 12 months, how often did you participate in sports or exercising?” [24]). These questionnaires often used exercise (defined as a subtype of PA that is repetitive and structured, and has a specific intention of improving or maintaining fitness [48]) as a proxy for the overall PA. The wide range of measurement tools utilized to estimate the PA led to inconsistent PA categorizations (i.e., different studies used the same terminologies (e.g., “physically active”) to describe a wide range of different intensities/types/frequencies of PA), thus compromising the current review’s ability to compare and synthesize included studies in a systematic manner.

Mood disorders

Nineteen out of twenty-two studies examined the association between mood disorders and PA. Most (15/19) focused on depressive disorder, but three examined wider diagnostic entities to include dysthymia [46] and bipolar disorders [29, 44, 45]. Of these 19 studies, 15 [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41, 44,45,46] examined the relationship between PA at baseline and subsequent mood disorders; eleven [30,31,32,33, 37,38,39,40,41, 44, 45] of which examined for incident (new onset) mood disorders, whilst four studies [34,35,36, 46] did not measure the baseline mood disorder status. One [33] also examined the effect of persistent depression on PA. Five studies [25, 27,28,29,30] examined the impact of mood disorder at baseline on subsequent PA.

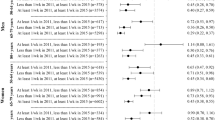

In terms of incident mood disorders, 5 out of 11 studies [33, 39,40,41, 44] found no association between PA at baseline and subsequent onset of mood disorders. Two studies [30, 37] found significant association between higher PA and a reduced likelihood of incident mood disorders. The remaining four studies had mixed results; Mikkelsen et al. [32] found that women with low PA had an increased likelihood of incident depression compared to those with high PA (1.80; 95% CI 1.29–2.51). There were no significant associations between women with moderate PA compared to high PA (1.07; 95% CI 0.80–1.44), or in men (1.11; 95% CI 0.73–1.68 with moderate PA and 1.39; CI 0.83–2.34 with low PA, both compared to the high PA group). Tanaka et al. [38], on the other hand, found that men who reported to “never” engage in PA had an increased risk of incident depression compared to those who reported to “often, sometimes” engage in PA (2.58; 95% CI 1.31–5.05). There was no significant association between the two variables found in women in this study (1.23; 95% CI 0.69–2.21). Ten Have et al. [45] found that those who engaged in between 1 and 3 h per week exercising (0.62; 95% CI 0.43–0.89), but not in those who exercised for more than 4 h per week (0.79; 95% CI 0.53–1.18), had a reduced risk of subsequent mood disorders compared to those who engaged in no exercise. Finally, Hallgren et al. [31] found that compared to those who did not achieve the WHO recommendation (150 min of moderate-to-vigorous PA per week), those who engaged in PA exceeding the WHO recommendation (over 300 min of moderate-to-vigorous PA per week) had a reduced risk of subsequent major depressive disorder (0.71; 95% CI 0.53–0.96), but not those who achieved the WHO recommendation (0.86; 95% CI 0.64–1.14).

Four studies examined the association of baseline PA and subsequent mood disorders without assessing for baseline mood disorder diagnoses, making it impossible to determine if these were incident cases or not. One study [34] found no association between PA and mood disorders in adolescents, while another study [35] found that lower PA was associated with an increased risk of subsequent depression. Using the response to the question: “How often did you exercise or play sports in the last week?”, Suetani et al. [46] found that compared to adolescents who engaged in frequent PA (more than 4 days), those with no PA engagement (“Not at all”) had an increased risk of subsequent mood disorders (1.79; 95% CI 1.05–3.06). However, there was no association between the two variables when the infrequent PA engagement (1–3 days) was compared to the frequent PA engagement group (1.05; 95% CI 0.83–1.32). McKerracher et al. [36] used a self-reported past-week frequency and duration of school and extracurricular sport and exercise at baseline (aged 9–15), and the long-form IPAQ at follow-up (approximately 20 years later) [47] to categorize participants into four PA groups [49]; (1) decreasing, (2) increasing, (3) persistently active, and (4) persistently inactive. The study found that compared to men in the persistently inactive group, men in the increasing group (0.31; 95% CI 0.11–0.92) or the persistently active PA group (0.35; 95% CI 0.15–0.81), but not those in the decreasing group (0.40; 95% CI 0.15–1.05), had a reduced risk of subsequent depression. No difference among the four groups was seen in women [36].

Five studies examined the effect of mood disorders on subsequent PA. Jerstad et al. found that adolescent girls with depression were less likely to engage in PA (compared to the non-depressed cohort) 6 years later [30]. Three studies [25, 27, 29] found no association between depression at baseline and subsequent PA. One study [28] found that participants with baseline depression who were active (defined in this study as the total estimated energy expenditure greater than 1.5 kcal/kg per day) had a greater likelihood of transitioning into being physically inactive compared to those without depression (1.6; 95% CI 1.2–1.9). However, among those who were physically inactive at baseline, depression was not associated with the transition into being physically active at follow-up (1.0; 95% CI 0.8–1.2).

Overall, these studies reveal an inconsistent pattern of associations between PA and mood disorders.

Anxiety disorders

Six studies [25, 29, 42, 44,45,46] examined the association between anxiety disorders and PA. Of these, three studies [42, 44, 45] examined incident anxiety disorders and one study [46] did not examine baseline anxiety disorders. Two studies explored the impact of anxiety disorders on subsequent PA [25, 29].

Of three studies examining incident anxiety disorders, Strohle et al. [44] found that compared to those engaged in no PA (defined in this study as less than once a month or no exercise at all), participants who were engaged in regular PA, defined in this study as daily and several times a week (0.52; 95% CI 0.37–0.74), but not in non-regular PA, defined in this study as one-to-four times a month (0.73; 95% CI 0.45–1.19), showed a reduced risk of subsequent anxiety disorders. On the other hand, Ten Have et al. [45] found that compared to those engaged in no exercise, participants who engaged in between 1 and 3 h per week of exercise (0.56; 95% CI 0.40–0.79), but not those who engaged in more than 4 h per week of exercise (0.71; 95% CI 0.48–1.07), showed a reduced risk of subsequent anxiety disorders. Furthermore, McDowell et al. [42] and Suetani et al. [46] found no association between PA status and subsequent generalised anxiety disorder diagnosis. Overall, these studies suggest no consistent association between PA and subsequent anxiety disorders.

Two studies that examined the association between the baseline anxiety disorders and subsequent PA had conflicting findings. Hiles et al. [25] found that the baseline anxiety disorders diagnosis was associated with reduced subsequent PA [25], whereas Suetani et al. [29] found no association.

Substance use disorders

Six studies examined the association between substance use disorders and PA [24, 29, 43,44,45,46]. Two studies explored alcohol use disorder, and the remaining four explored substance use disorders in general. One study [45] found no association between PA and subsequent substance use disorders. Three studies found mixed results. Ejsing et al. [43] found that compared with those with a moderate/high PA level, participants with a sedentary level (1.45; 95% CI 1.01–2.09 in woman, 1.64; 95% CI 1.29–2.10 in men), but not those with a low PA level (0.88; 95% CI 0.64–1.19 in woman, 1.15; 95% CI 0.93–1.42 in men), had an increased risk of subsequent alcohol use disorder. This finding was found in both men and women. Likewise, Henchoz et al. found that participants engaging in no sports or exercise (2.32; 95% CI 1.60–3.35 in “never”), but not those with lower engagement (1.14; 95% CI 0.79–1.65 in “a few times a year”, 1.09; 95% CI 0.80–1.49 in “1–3 times per month”, and 1.16; 95% CI 0.92–1.46 in “at least once per week”), had an increased risk of subsequent alcohol use disorders compared to those who engaged in sports or exercise “almost every day” [24]. Strohle et al. [44] found that non-regular PA (0.48; 95% CI 0.31–0.75), but not regular PA (0.95; 95% CI 0.72–1.24), was associated with a reduced risk of subsequent substance use disorders (compared to those with no PA). Finally, Suetani et al. [46] found that adolescents who engaged in infrequent PA (0.75; 95% CI 0.62–0.91), but not those who engaged in no PA (0.92; 95% CI 0.56–1.51), had a reduced risk of substance use disorders compared to adolescents who engaged in frequent PA. Overall, there was no consistent association across all studies of PA and subsequent substance use disorders.

Only one study [29] examined the association between the baseline substance use disorders and subsequent PA, and found no association.

Psychotic disorders

Only one study examined the association between PA and psychotic disorders. Suetani et al. [46] did not find any association between the baseline PA and subsequent psychotic disorders.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment scores for included studies are summarized in Table 2. The mean score was 7.1 with the lowest score of 5 and the highest score of 8.

The majority (17 out of 22) of included studies scored equal to or higher than the mean score (i.e., the NOS score of at least 7 out of 9). One study [37] found a consistent association between higher PA and a reduced risk of depression. Another study [30] found the bidirectional beneficial association between PA and depression. Ten studies [25, 28, 31,32,33, 36, 43,44,45,46] found mixed results (i.e., no consistency in direction and significance of the findings), and five studies [27, 29, 34, 39, 41] found no association between PA and mental disorder diagnoses.

Discussion

Summary of evidence

We would like to draw attention to three key findings. First, apart from depression, there has been relatively little research examining the association between PA and mental disorders using clinical diagnostic criteria. Second, there is a wide range of different methods used to measure and classify PA, thus making it difficult to compare one study from another. Third, the findings from this review suggest that there are no convincing data to support the hypothesis that PA influences the risk of subsequent mental disorders, nor that mental disorders influence subsequent PA.

Within 22 included studies, only two found consistent association between lower PA and a reduced risk of subsequent mental disorders. One study found the bidirectional association (i.e., greater PA was associated with a reduced likelihood of subsequent major depression and major depression predicted lower subsequent PA engagement). Twelve studies found mixed results (i.e., no consistency in direction and significance of the findings). Seven studies found no association.

Previously, Mammen and Faulkner [10] reported that 25 out of 30 longitudinal studies identified in their review showed the association between greater PA and a reduced subsequent risk of developing depression. However, only five [30, 32, 37, 39, 41] of the 30 studies included in their study met the inclusion criteria for the current review (due to this review having a narrower definition of mental disorders). Similarly, Hoare et al. [18] have identified six longitudinal studies that examined the association between PA and subsequent depressive symptoms among adolescents. Even though all six studies found the association between greater PA and a reduced subsequent risk of depressive symptoms with one study also demonstrating the opposite direction of association, only one out of the six studies included [30] met the inclusion criteria for the current review. The rationale for the tighter inclusion criteria for this study was so that the findings were more relevant to those individuals who attended specialist mental health services. Requiring a diagnostic threshold favored studies examining the association between PA and mental disorders where participants had more severe symptom profiles. This is in contrast to previous reviews [12, 21] which included studies of people who had mental health symptoms which may not reflect those who would seek help from mental health service providers. Our findings are, therefore, more applicable to patient populations but not generalizable to the non-clinical population.

There has been little attention given to the association between the PA and subsequent anxiety, substance use, and psychotic disorders. In the current review, six studies [25, 29, 42, 44,45,46] examined the association between PA and anxiety disorders. Another six studies [24, 29, 43,44,45,46] examined the association between PA and subsequent substance use disorders, and only one study examined the relationship between PA and psychotic disorders [46]. Overall, there was no consistent association among these studies.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the current analysis included the focus on participants with more robust definitions of mental disorders, thus allowing the findings to have more clinical utility compared to previous reviews. It also focused on data from longitudinal studies, facilitating a better exploration of the temporal association between PA and mental disorders.

The main limitation of the current analysis is the inconsistency in measurement and definition of PA in the included studies and absence of objective measurement of PA. As PA is often unstructured and varies in both intensity and duration as well as type, measuring and assessing PA are inherently complex [50]. Furthermore, the risk of under-reporting with self-report measurements may be particularly high in people with mental disorders. Given that all the studies included in this review relied on self-reports rather than objective measurements, and the proportion of participants focused were those with mental disorders, the risk of under-reporting due to both recall/reporting biases and methodological effectiveness of the tools used is likely to be substantial.

It should also be noted that this review had stronger emphasis on the statistical significance, rather than the effect size, of each association in interpreting the findings of the original studies. Some studies were classified as either having no or mixed association even when the effect sizes were large (e.g., in one study [36], men in the decreasing group compared to the persistently inactive group had the adjusted relative risk of subsequent depression at 0.40. However, as its 95% CI was between 0.15 and 1.05, the study was classified as having a mixed association). This is particularly important given that a meta-analysis was not conducted in this review. It is possible that the effect of PA may have been underestimated by taking this approach.

The majority of included studies measured mental disorder diagnoses at both time points to allow for the estimate of incident, or change in mental disorder diagnosis status. This allowed the current review to investigate if PA was associated with the change in the outcome (mental disorder diagnosis status), rather than just examining the association between the two variables at different time points. However, few included studies accounted for the change in PA status using a consistent measurement tool over the same period of time, which limited our ability to examine the change in the PA status in the same manner.

Another important limitation is that the current review only included observational studies. While most of the included studies controlled for potential confounders such as age, sex, and body mass index, only few of them considered other factors like smoking status, other medical conditions, and socioeconomic status, and none of them included factors like cardiorespiratory function. There may be other unmeasured confounding factors that may influence the association between the two variables in any given observational study. Given these limitations, even though the current review restricted its search to longitudinal studies only, it is unable to comment on causative factors between mental disorders and PA. This may, at least in part, explain why the results of the current review are not in line with the accumulating base of research evidence from interventional studies that indicate that PA is beneficial to people with mental disorders [7, 8].

The current review highlights the need for researchers in this field to explore an appropriate and consistent tool to measure PA in large cohort studies with more robust designs. While objective measurements such as accelerometers may have more favorable features in terms of validity, reliability, and sensitivity when measuring PA, this needs to be weighed against practical issues such as cost, feasibility, acceptability, and tolerance, especially if the study requires the participants to wear these devices for a considerable amount of time. Furthermore, given how rapidly the technology is advancing, most measurement devices that are used at the baseline data collection may be out of date by the follow-up point in longitudinal studies with long durations. Thus, subjective-validated measurement tools such as self-report questionnaire still have an important role [51].

In addition to how PA is measured, future studies should also consider the timing of the PA (e.g., at specific ages across the lifespan) and the duration of the PA (e.g., years as opposed to weeks). They should also examine how PA may impact on both physical and psychiatric outcomes both in the short term (e.g., changes in cardiometabolic parameters and symptom severity), and in the long term (e.g., changes in life expectancies and disease progression) for people with mental disorders. Future studies should incorporate novel designs that may help to strengthen the exploration of the causative natures of the relationship such as Mendelian comparison and sibling comparison on a large scale in a collaborative manner [52, 53]. For example, Choi et al. [54] recently investigated the bidirectional relationship between depression and PA using Mendelian Randomization. This study found that people with increased PA had reduced likelihood of developing depression, but the association was evident only when objectively measure PA, not self-reported PA, was used. They found no association between depression and subsequent PA status regardless of how PA was measured.

Conclusion

While the evidence base for PA as an effective intervention option among people with mental disorders is growing [55], there remains a lack of consistent epidemiological evidence linking PA to be either a risk factor or consequence of mental disorders. Therefore, it may be important not to overstate the benefit of PA in mental health service settings at this stage. The current review found the need for a more consistent approach to measuring and defining PA, as well as incorporating novel approaches to account for inherent complexities of PA among people with mental disorders. Given the potential importance of PA at both the individual and population levels [56], this issue warrants ongoing attention.

References

Scott KM, Lim C, Al-Hamzawi A, Alonso J, Bruffaerts R, Caldas-de-Almeida JM, Florescu S, de Girolamo G, Hu C, de Jonge P, Kawakami N, Medina-Mora ME, Moskalewicz J, Navarro-Mateu F, O’Neill S, Piazza M, Posada-Villa J, Torres Y, Kessler RC (2016) Association of mental disorders with subsequent chronic physical conditions: world mental health surveys from 17 countries. JAMA Psychiatry 73(2):150–158. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2688

Galletly CA, Foley DL, Waterreus A, Watts GF, Castle DJ, McGrath JJ, Mackinnon A, Morgan VA (2012) Cardiometabolic risk factors in people with psychotic disorders: the second Australian national survey of psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 46(8):753–761. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867412453089

Hjorthoj C, Sturup AE, McGrath JJ, Nordentoft M (2017) Years of potential life lost and life expectancy in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 4(4):295–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30078-0

Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG (2015) Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 72(4):334–341. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502

Stubbs B, Firth J, Berry A, Schuch FB, Rosenbaum S, Gaughran F, Veronesse N, Williams J, Craig T, Yung AR, Vancampfort D (2016) How much physical activity do people with schizophrenia engage in? A systematic review, comparative meta-analysis and meta-regression. Schizophr Res 176(2–3):431–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2016.05.017

Schuch F, Vancampfort D, Firth J, Rosenbaum S, Ward P, Reichert T, Bagatini NC, Bgeginski R, Stubbs B (2016) Physical activity and sedentary behavior in people with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 210:139–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.050

Rosenbaum S, Tiedemann A, Sherrington C, Curtis J, Ward PB (2014) Physical activity interventions for people with mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 75(9):964–974. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.13r08765

Rosenbaum S, Tiedemann A, Stanton R, Parker A, Waterreus A, Curtis J, Ward PB (2016) Implementing evidence-based physical activity interventions for people with mental illness: an Australian perspective. Australas Psychiatry 24(1):49–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856215590252

Firth J, Cotter J, Elliott R, French P, Yung AR (2015) A systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise interventions in schizophrenia patients. Psychol Med 45(7):1343–1361. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714003110

Mammen G, Faulkner G (2013) Physical activity and the prevention of depression: A systematic review of prospective studies. Am J Prev Med 45(5):649–657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.08.001

Roshanaei-Moghaddam B, Katon WJ, Russo J (2009) The longitudinal effects of depression on physical activity. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 31(4):306–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.04.002

Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Firth J, Rosenbaum S, Ward PB, Silva ES, Hallgren M, Ponce De Leon A, Dunn AL, Deslandes AC, Fleck MP, Carvalho AF, Stubbs B (2018) Physical activity and incident depression: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am J Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17111194

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 62(10):1006–1012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB (2000) Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 283(15):2008–2012

Teychenne M, Ball K, Salmon J (2008) Physical activity and likelihood of depression in adults: a review. Prev Med 46(5):397–411

Korczak DJ, Madigan S, Colasanto M (2017) Children’s physical activity and depression: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 139(4):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2266

Janssen I, LeBlanc AG (2010) Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-7-40

Hoare E, Skouteris H, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Millar L, Allender S (2014) Associations between obesogenic risk factors and depression among adolescents: a systematic review. Obes Rev 15(1):40–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12069

Dunn AL, Trivedi MH, O’Neal HA (2001) Physical activity dose-response effects on outcomes of depression and anxiety. Med Sci Sports 33(6 SUPPL.):S587–S597

Bardo MT, Compton WM (2015) Does physical activity protect against drug abuse vulnerability? Drug 153:3–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.05.037

Azar D, Ball K, Salmon J, Cleland V (2008) The association between physical activity and depressive symptoms in young women: a review. Ment Health 1(2):82–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2008.09.004

Stubbs B, Williams J, Gaughran F, Craig T (2016) How sedentary are people with psychosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 171(1–3):103–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2016.01.034

Wells GS, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed Jan 2018

Henchoz Y, Baggio S, N’Goran AA, Studer J, Deline S, Mohler-Kuo M, Daeppen JB, Gmel G (2014) Health impact of sport and exercise in emerging adult men: a prospective study. Qual Life Res 23(8):2225–2234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0665-0

Hiles SA, Lamers F, Milaneschi Y, Penninx B (2017) Sit, step, sweat: longitudinal associations between physical activity patterns, anxiety and depression. Psychol Med 47(8):1466–1477. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716003548

Okkenhaug A, Tanem T, Johansen A, Romild UK, Nordahl HM, Gjervan B (2016) Physical activity in adolescents who later developed schizophrenia: a prospective case-control study from the Young-HUNT. Nord J Psychiatry 70(2):111–115. https://doi.org/10.3109/08039488.2015.1055300

Naicker K, Galambos NL, Zeng Y, Senthilselvan A, Colman I (2013) Social, demographic, and health outcomes in the 10 years following adolescent depression. J Adolesc Health 52(5):533–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.12.016

Patten SB, Williams JV, Lavorato DH, Eliasziw M (2009) A longitudinal community study of major depression and physical activity. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 31(6):571–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.08.001

Suetani S, Mamun A, Williams GM, Najman JM, McGrath JJ, Scott JG (2019) The association between the longitudinal course of common mental disorders and subsequent physical activity status in young adults: a 30-year birth cohort study. J Psychiatr Res 109:173–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.12.003

Jerstad SJ, Boutelle KN, Ness KK, Stice E (2010) Prospective reciprocal relations between physical activity and depression in female adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol 78(2):268–272. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018793

Hallgren M, Nguyen TTD, Lundin A, Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, Schuch F, Bellocco R, Lagerros YT (2019) Prospective associations between physical activity and clinician diagnosed major depressive disorder in adults: a 13-year cohort study. Prev Med 118:38–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.10.009

Mikkelsen SS, Tolstrup JS, Flachs EM, Mortensen EL, Schnohr P, Flensborg-Madsen T (2010) A cohort study of leisure time physical activity and depression. Prev Med 51(6):471–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.09.008

Cabello M, Miret M, Caballero FF, Chatterji S, Naidoo N, Kowal P, D’Este C, Ayuso-Mateos JL (2017) The role of unhealthy lifestyles in the incidence and persistence of depression: a longitudinal general population study in four emerging countries. Glob Health 13(1):18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-017-0237-5

Colman I, Zeng Y, McMartin SE, Naicker K, Ataullahjan A, Weeks M, Senthilselvan A, Galambos NL (2014) Protective factors against depression during the transition from adolescence to adulthood: findings from a national Canadian cohort. Prev Med 65:28–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.04.008

Jacka FN, Pasco JA, Williams LJ, Leslie ER, Dodd S, Nicholson GC, Kotowicz MA, Berk M (2011) Lower levels of physical activity in childhood associated with adult depression. J Sci Med Sport 14(3):222–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2010.10.458

McKercher C, Sanderson K, Schmidt MD, Otahal P, Patton GC, Dwyer T, Venn AJ (2014) Physical activity patterns and risk of depression in young adulthood: a 20-year cohort study since childhood. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 49(11):1823–1834. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-0863-7

Strawbridge WJ, Deleger S, Roberts RE, Kaplan GA (2002) Physical activity reduces the risk of subsequent depression for older adults. Am J Epidemiol 156(4):328–334

Tanaka H, Sasazawa Y, Suzuki S, Nakazawa M, Koyama H (2011) Health status and lifestyle factors as predictors of depression in middle-aged and elderly Japanese adults: a seven-year follow-up of the Komo-Ise cohort study. BMC Psychiatry 11:20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-11-20

Wang F, DesMeules M, Luo W, Dai S, Lagace C, Morrison H (2011) Leisure-time physical activity and marital status in relation to depression between men and women: a prospective study. Health Psychol 30(2):204–211. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022434

Zhang XC, Woud ML, Becker ES, Margraf J (2018) Do health-related factors predict major depression? A longitudinal epidemiologic study. Clin Psychol Psychother. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2171

Weyerer S (1992) Physical inactivity and depression in the community. Evidence from the Upper Bavarian Field Study. Int J Sports Med 13(6):492–496. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-1021304

McDowell CP, Dishman RK, Vancampfort D, Hallgren M, Stubbs B, MacDonncha C, Herring MP (2018) Physical activity and generalized anxiety disorder: results from The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). Int J Epidemiol 47(5):1443–1453. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyy141

Ejsing LK, Becker U, Tolstrup JS, Flensborg-Madsen T (2015) Physical activity and risk of alcohol use disorders: results from a prospective cohort study. Alcohol Alcohol 50(2):206–212. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agu097

Strohle A, Hofler M, Pfister H, Muller AG, Hoyer J, Wittchen HU, Lieb R (2007) Physical activity and prevalence and incidence of mental disorders in adolescents and young adults. Psychol Med 37(11):1657–1666. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329170700089X

Ten Have M, de Graaf R, Monshouwer K (2011) Physical exercise in adults and mental health status findings from the Netherlands mental health survey and incidence study (NEMESIS). J Psychosom Res 71(5):342–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.04.001

Suetani S, Mamun A, Williams GM, Najman JM, McGrath JJ, Scott JG (2017) Longitudinal association between physical activity engagement during adolescence and mental health outcomes in young adults: A 21-year birth cohort study. J Psychiatr Res 94:116–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.06.013

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, Pratt M, Ekelund U, Yngve A, Sallis JF, Oja P (2003) International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 35(8):1381–1395. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB

Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM (1985) Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep 100(2):126–131

Group TI (2005) IPAQ scoring protocol. Accessed June 2015

Knowles G et al (2017) Physical activity and mental health: commentary on Suetani et al. 2016: common mental disorders and recent physical activity status: findings from a National Community Survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 52(7):803–805. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1399-4

Bauman A, Ainsworth BE, Bull F, Craig CL, Hagstromer M, Sallis JF, Pratt M, Sjostrom M (2009) Progress and pitfalls in the use of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) for adult physical activity surveillance. J Phys Act Health 6(Suppl 1):S5–S8

Wade KH, Richmond RC, Davey Smith G (2018) Physical activity and longevity: how to move closer to causal inference. Br J Sports Med. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-098995

Kujala UM (2018) Is physical activity a cause of longevity? It is not as straightforward as some would believe. A critical analysis. Br J Sports Med. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-098639

Choi KW, Chen CY, Stein MB, Klimentidis YC, Wang MJ, Koenen KC, Smoller JW, Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics C (2019) Assessment of bidirectional relationships between physical activity and depression among adults: a 2-sample mendelian randomization study. JAMA Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4175

Lederman O, Suetani S, Stanton R, Chapman J, Korman N, Rosenbaum S, Ward PB, Siskind D (2017) Embedding exercise interventions as routine mental health care: implementation strategies in residential, inpatient and community settings. Australas Psychiatry 25(5):451–455. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856217711054

Suetani S, Rosenbaum S, Scott JG, Curtis J, Ward PB (2016) Bridging the gap: What have we done and what more can we do to reduce the burden of avoidable death in people with psychotic illness? Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 25(3):205–210. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796015001043

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following researchers for providing additional data; Yves Henchoz from Lusanne University Hospital, Sarah Hiles from VU University Medical Center, and Arne Okkenhaug from Levanger Hospital.

Funding

JGS is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Practitioner Fellowship Grant (APP1105807) and employed by The Queensland Centre for Mental Health Research which receives core funding from the Queensland Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SS, JJM, and JGS planned the study. BS and SS conducted data extraction and methodological quality appraisal. SS and JGS wrote the initial drafts of the manuscript. All authors were involved in later revisions and all authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Suetani, S., Stubbs, B., McGrath, J.J. et al. Physical activity of people with mental disorders compared to the general population: a systematic review of longitudinal cohort studies. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 54, 1443–1457 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01760-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01760-4