Abstract

This paper presents an approach for evaluating the reliability and validity of mental health measures in non-Western field settings. We describe this approach using the example of our development of the Acholi psychosocial assessment instrument (APAI), which is designed to assess depression-like (two tam, par and kumu), anxiety-like (ma lwor) and conduct problems (kwo maraco) among war-affected adolescents in northern Uganda. To examine the criterion validity of this measure in the absence of a traditional gold standard, we derived local syndrome terms from qualitative data and used self reports of these syndromes by indigenous people as a reference point for determining caseness. Reliability was examined using standard test–retest and inter-rater methods. Each of the subscale scores for the depression-like syndromes exhibited strong internal reliability ranging from α = 0.84–0.87. Internal reliability was good for anxiety (0.70), conduct problems (0.83), and the pro-social attitudes and behaviors (0.70) subscales. Combined inter-rater reliability and test–retest reliability were good for most subscales except for the conduct problem scale and prosocial scales. The pattern of significant mean differences in the corresponding APAI problem scale score between self-reported cases vs. noncases on local syndrome terms was confirmed in the data for all of the three depression-like syndromes, but not for the anxiety-like syndrome ma lwor or the conduct problem kwo maraco.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

The war in northern Uganda, which has continued for over two decades, remains one of the world’s most enduring and devastating conflicts in recent times [30]. Greater than 1.8 million people, most of them ethnic Acholi, have been internally displaced and forced to live in overcrowded camps [33]. Efforts to reliably and validly assess the burden of war on the mental health of youth in such settings have been hampered by the lack of culturally appropriate and psychometrically sound mental health assessments [26]. Although some researchers have adapted Western mental health assessments [25] based on DSM diagnostic criteria [17] for use in war-affected environments, very few of these measures have been explored for their reliability and validity among non-Western populations, such as the Acholi of northern Uganda.

Researchers acknowledge methodological challenges associated with using standard Western diagnostic instruments in populations that differ dramatically from those in which they were developed [21, 22]. These challenges are often addressed in a variety of ways. Some studies employ translated instruments that are recommended for low-resource contexts but which have not been used previously in the specific study population [5, 10, 11, 27, 31]. Others modify mental health measures for cross-cultural use by identifying and integrating local terms into the standard language designed originally for use in (Western) cultures [25, 28]. Regardless of whether instruments are adapted or developed specifically for the local context, the psychometric properties of these measures must be rigorously evaluated.

The reliability and validity of measures remains a central issue in cross-cultural mental health research performed in non-Western cultures. Reliability addresses the degree to which empirical measures result in reproducible results across different interviewers and applications [32]. Validity refers to the degree to which an empirical tool actually measures the construct of interest [16, 20]. Although reliability and validity are two central concepts in mental health measurement, reliability is more commonly investigated in international research with less attention given to the critical issue of validity in measurement across cultural groups.

When criterion validity is considered, the most commonly used criterion for the validation assessment is a clinical diagnosis made by a mental health professional, most often a psychiatrist [36]. In many conflict-affected and non-Western environments there are two common barriers to using this traditional ‘gold standard’ process to assess criterion validity. The first challenge is the frequent lack of trained mental health professionals. In many conflict-affected regions, the few professionals available are often located at major psychiatric hospitals in capital cities and rarely work in regions directly affected by conflict. In Uganda, for example, the war has affected mainly the Acholi people who live in the northern regions of the country. While there are some psychiatrists and psychologists in the Acholi north who are familiar with the local language and culture, most are concentrated in the capital, Kampala. The second challenge is more fundamental. Most local mental health professionals are trained in Western-based psychiatry, with the models of disorder being derived from the DSM or ICD classification schemes. When working with non-Western populations where research has not yet determined if Western-models apply, it may be inappropriate to have those trained in Western psychiatry as the main criteria against which to judge validity [6]. Therefore, we are presenting here a process that may be employed when such limitations exist to implementing a traditional ‘gold standard’ validation process—by asking local people to identify the presence and absence of locally-recognized syndromes derived from qualitative data. These qualitative methods are described in more detail elsewhere [9, 13].

The study presented here builds on methods originally developed for research among adults to identify salient mental health problems as well as select, adapt and validate appropriate mental health measures [12]. These methods have been used in other countries including the Democratic Republic of Congo [7], and in southern Uganda [15]. The present study adapts the methodology used in these studies by applying this approach to: (a) developing a locally-derived measure; (b) adolescent populations; and (c) reports of caregivers as well as adolescents.

Methods

Measures

The Acholi psychosocial assessment instrument (APAI) was developed using data from a prior qualitative study among this same population [9]. Briefly, the study consisted of 45 free listing interviews with local youth and adults and 57 in-depth interviews with local key informants to identify and describe the important problems of youth in these camps for internally displaced people (IDPs). Among the many problems that emerged, we identified five common local mental health syndromes affecting Acholi youth in the camps: two tam, par, kumu, ma lwor, and kwo maraco. The symptoms of these local syndromes not only share similarities with Western definitions for mood disorders (two tam, par and kumu), general anxiety disorder (ma lwor) and conduct disorder (kwo maraco), but they also contain important culturally-specific descriptions of distress. For example, “sitting kumu” (sitting while holding one’s cheek in their hand) and not greeting people were described as hallmark symptoms of the local mood disorder kumu. The qualitative study also identified eight items indicative of prosocial behavior among youth in this setting.

To develop the APAI, we took the signs and symptoms that comprised each of the five local disorders and the information on local pro-social behaviors to generate individual questions and create a subscale for each. Table 1 presents the items that make up the APAI along with an indication of the specific items comprising each of the five syndrome and pro-social scales. The scoring format for the APAI was modeled on the youth self report (YSR), which is a tool developed to assess several domains of psychological problems among youth [2]. Respondents are asked about the frequency of each symptom during the previous week, with responses coded on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from ‘0’ (never) to ‘3’ (constantly). Symptoms that occur in more than one syndrome (i.e. sits alone) are only listed once in the APAI total problems score. An initial pilot study of the instrument with a group of youth from the nearby city of Gulu allowed us to modify and correct any problems with clarity, comprehension and language of the APAI measure prior to its use among youth living in camps for internally displaced people (IDPs).

Sample

The data were collected in the Unyama and Awer IDP camps in Gulu, Uganda during the summer of 2005. These two camps, the sites of our prior qualitative study, were selected because they represented the service catchment area of the nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) World Vision and War Child Holland, who actively participated in this research and provided the funding to implement it. Those eligible for the study were Acholi youth aged 14–17 years and their caregivers. The age range was selected because of plans to use the APAI for assessing adolescent participants in a controlled trial of interventions which followed the present study [14]. Adolescents who had lived in the camp for less than a month and those who did not speak the Acholi Luo language were excluded.

The focus of recruitment was to identify youth with and without the five mental health syndromes (kumu, par, two tam, ma lwor, and kwo maraco) that were identified in the earlier qualitative study [9]. To facilitate identification of potential survey participants, study supervisors visited with local, knowledgeable people identified by our NGO partners (i.e. teachers, camp leaders, and local NGO workers) and asked them to generate separate lists of adolescents they knew who had at least one of the five local mental health syndromes and of adolescents they thought had none of these syndromes. Approximately six key informants (three at each site) were asked to provide this information. Some key informants were the same as those who had participated in a prior qualitative study while others were community leaders with whom our NGO partners had worked and were considered to be knowledgeable about the problems of youth in the camps.

Our intent was to recruit a total of 250 young people (along with one caregiver each). Our previous experience with this method suggests that 50 pairs (self and another person) per subgroup usually provides adequate power to distinguish between cases and noncases of various disorders. Therefore, we would need at least 50 youth-caretaker pairs who agreed that the youth had none of the local syndromes and, for each syndrome, 50 youth-caretaker pairs who agreed that the youth had specific syndromes. Due to comorbidity between the disorders, the same young person could be on multiple lists. Thus, we estimated that we would need 100 adolescent-caretaker pairs in order to get 50 pairs for each syndrome, and 50 pairs for youth free of the syndromes, making a total of 150 pairs. Because many of those pairs would be discordant (youth and caretaker do not agree), and therefore not eligible for the analysis, we increased the sample size by 100 additional pairs for a total target sample size of 250.

Study protocol and syndrome assessment

A team of 20 local interviewers and 10 local supervisors carried out all data collection with oversight from the study investigators. The qualifications for the interviewers were that they were local adults known to the collaborating NGOs who spoke both Acholi Luo and English, and had, at minimum, a high school education. The supervisors were recruited from the team of interviewers who had participated in the prior qualitative study. All interviewers and supervisors received 3 days of training in research ethics, interviewing techniques and questionnaire administration by the study investigators. All interviews were conducted in private following informed consent. The study sample was collected via a two-stage procedure (see Fig. 1). In the first stage, a study supervisor asked each youth participant and their caregiver independently whether they believed that the participating adolescent had each of the five local syndromes contained in the APAI measure. Supervisors then assigned the adolescents and caregivers to one of the interviewers (blind to their syndrome status) who administered the survey (see Fig. 1).

To evaluate reliability, 30 participants randomly selected were re-interviewed by the same interviewer 1–3 days after the initial interview (test–retest), and 19 randomly selected participants were re-interviewed by different interviewers (inter-rater).

Statistical analyses

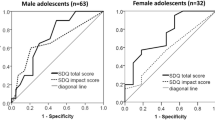

Individual local syndrome scale scores and a pro-social behavior scale score, along with a total APAI problems score, (all syndrome signs and symptoms excluding the pro-social behaviors), were generated for each study participant. The two APAI items relating to school (losing interest in school and concentration in class) were removed from all of the scale calculations because of problems with interpreting these items: although overall access to school in our sample was high (97%), lags in attendance due to family responsibilities were common in this camp setting. In addition, there was concern that these items were not interpreted consistently across all participants (i.e. some adolescents would endorse the items if they were not in school but still had interest whereas others would state that the item did not apply to them because they were not in school). Instrument reliability was assessed using Spearman-Brown “split half” and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for internal consistency and Pearson correlation coefficients for test–retest and inter-rater reliabilities. However, for kwo maraco (conduct problems), inter-rater reliability was assessed using Spearman coefficients since the data were not normally distributed. Individual item-analyses were conducted to evaluate whether the exclusion of any symptom improved the internal consistency of each problem scale.

For the validation analyses, “cases” were defined as those youth for whom both the adolescent and caregiver endorsed that the adolescent had the local syndrome of interest. “Noncases” were defined as those youth for whom both the adolescent and caregiver endorsed that the adolescent did not have the local syndrome of interest. Our intention was to create two youth groups, the ‘cases’, who were highly likely to have the particular syndrome and the ‘noncases’, who were highly unlikely to have the particular syndrome. Thus, the concordance of adolescent and caregiver report became the criterion by which we judged validity. Discordant cases (instances where just one of either the adolescent or caregiver endorsed the presence/absence of the syndrome without the agreement of the other) were interpreted as being uncertain with regards to the presence/absence of the syndrome in question and were therefore removed from the analysis for that syndrome. To examine validity we compared the mean scale scores of cases to non-cases for each of the syndrome scales, with our expectation being that cases would have significantly higher mean scores compared to non-cases. All statistical analyses were performed using the SAS software system, version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

The final sample size was 178 adolescents, with 166 (93%) having complete information and classified by agreement of youth and caregiver reports as either cases or non-cases for each of the five local syndromes under study. Given significant difficulty in finding 50 cases free of any mental health syndromes and 50 cases of conduct problems in the sample, data collection concluded when approximately 50 concordant observations were available for each of the other four local syndromes.

Table 2 summarizes the sample demographics. The average age of the participants was 14.6 years. On average, the youth had completed 5 years of education and had lived in the camps for more than 5 years. Forty-two percent of the adolescents reported a history of abduction by the rebel lords resistance army (LRA) that operates in the region.

With regard to reliability, each of the depression-like syndrome scales and the total depression scale (a single scale developed that combined the symptoms of two tam, par and kumu syndromes, not counting repeated items) exhibited strong internal consistency with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from 0.84 to α = 0.93 (Table 3). The Spearman-Brown coefficients for these subscales split into odd and even-numbered items showed similar results ranging from 0.82 to 0.95. The internal reliability of the ma lwor (anxiety syndrome), kwo maraco (conduct problems) and the pro-social scales were all adequate (i.e. at least 0.70 for both the Cronbach’s alpha and Spearman-Brown coefficient). The total APAI problem score (a single scale including the symptoms of the 5 local syndromes and excluding the pro-social items) had strong internal consistency (α = 0.93, s-b α = 0.93). Inter-rater reliability and test–retest reliability was good for all the APAI depression like problem scales (Table 3). However, test–retest and inter-rater reliability was less strong for the anxiety problem ma lwor (0.68 and 0.62 respectively) while the conduct problem scale (kwo maraco) and the prosocial scale exhibited poor inter-rater reliability (0.25 and 0.35 respectively).

A total of 50 ‘cases’ were identified by agreement between both the adolescent and caregiver as having two tam, 97 with kumu, 112 with par, 68 with ma lwor and 13 with kwo maraco (recognizing that comorbidity was common). Only 12 adolescents were identified by agreement of both adolescent and caregiver report as having none of the five locally-relevant mental health syndromes (their data is not provided). The mean scale scores for those identified as having these syndromes (‘cases’) compared with those identified as not having them (‘non-cases’) are presented in Table 4. As shown in Table 4, the expected pattern of significant mean differences across case status was confirmed for all three depression-like syndromes (two tam, kumu, par). The mean scores for the corresponding scale scores of ‘cases’ of the anxiety syndrome ma lwor and the conduct problem syndrome kwo maraco were not significantly different from ‘non-cases’.

Comorbidity was common in the sample (Tables 5, 6). For example, looking at the three depression-like syndromes (par, kumu and two tam), none of the participants reported having just one of these local syndromes. Par emerged as a very common syndrome and was identified in 67% of the sample screened. Of those adolescents identified as cases of par, 77% were also identified as cases of kumu and 41% as cases of two tam.

Discussion

The present study builds upon a prior qualitative study [9] that initially identified the local syndromes measured by the APAI. The results of this quantitative study, together with the qualitative data, provide evidence that the scales designed to assess the three depression-like local syndromes (two tam, kumu, par) exhibited satisfactory reliability and validity. Reliability and validity of the local conduct problem scale (kwo maraco) and the local anxiety-like problem scale (ma lwor) were not supported by the data.

Overall, our findings suggest that there are not absolute boundaries between the three depression-like syndromes (par, two tam and kumu) and the anxiety syndrome (ma lwor). This agrees with the literature on depression and anxiety that has demonstrated high comorbidity between anxiety and depression [23] and strong correlations between dimensional scales assessing anxiety and depression [1–3]. However, our finding of empirical support for distinctions between ‘cases’ and ‘non-cases’ for all three locally-defined depression-like problems indicates that there are some unique symptom expressions between those with and without each of these local syndromes.

A number of study limitations must be noted. First, the initial effort to recruit 50 adolescent and adolescent cases said to have each of the syndromes and 50 noncases was not achieved. We recognize that finding 50 adolescents said to have no mental health syndromes in a war zone may prove exceedingly difficult. In this light, such an outcome is not particularly surprising. In the future, to identify a sizeable sample of youth with no mental health syndromes, we may need to substantially over-sample youth considered by local people to be entirely free of mental health problems. This small sample size may have contributed to the lack of significant differences observed when comparing problem scale scores between local syndrome ‘cases’ and ‘non-cases’ for conduct disorders (kwo maraco) which were endorsed far less frequently. An additional possible explanation for the lack of significant differences is the potential for misclassification of caseness. The differences between ‘cases’ and ‘non-cases’ were all in the expected direction, and use of local terminology for the syndromes and the classification of cases/noncases based on both caregivers and youth should have minimized the potential for this type of problem. However, it is still possible that some adolescents and their caretakers may have made misclassifications either because of uncertainty about the nature of the local disorders or about whether they had them or both. Ambiguities in the language may contribute to uncertainty about the nature of the disorders. For instance, ‘par’ is both the name of a locally-relevant syndrome and also the name of a symptom common across two of the three depression-like syndromes. In administering our study, we were aware of this challenge and addressed it in the way that the symptom items versus the syndromes were asked about. The Acholi Luo phrasing was such that a distinction was made between “feeling par” (for the symptom) and “having par” (for the syndrome).

An additional limitation of this study relates to discordant reporting between adolescents and caregivers. As the Western literature has demonstrated, it is quite common for the reports of caregivers and adolescents to diverge [29]. However, where parents and adolescents do agree on the presence or absence of a disorder, then it is much more likely that the assessment of each is accurate. The degree to which parent vs. adolescent reports are weighed may need to vary depending on whether internalizing or externalizing problems are being considered [35], which may allow for further consideration of discordant cases.

The poor inter-rater reliability found for the local conduct problem, kwo maraco may be one example where issues of embarrassment resulted in poor or inconsistent reporting. Given the potential stigma associated with a condition that translates literally as “having a bad lifestyle,” accurate reporting by adolescents and caregivers may be unlikely and may pose difficulties for relying on agreement between caregiver and adolescent reports. Nonetheless, meta-analyses in Western cultures assessing parent-adolescent reports have demonstrated greater agreement on externalizing problems such as aggression, hyperactivity, or conduct problems compared to internalizing problems such as anxiety or depression [4, 18]. Such findings indicate that agreement in adolescent and caregiver reports may be greater for more observable problems such as hyperactivity or fighting compared to more internal problems such as feeling sad or anxious. As it was we could not recruit sufficient pairs who agreed to the presence of kwo maraco and we suspect that significant numbers of those who were said not to have it may have been unwilling to admit to it. In future applications, we will explore including additional assessments by other local people, such as teachers and local mental health workers knowledgeable of local syndrome terms when available, and basing the designation of cases and non-cases on agreement of two out of three informants including the subject themselves.

There are a number of strengths to the approach presented here for examining the reliability and validity of mental health measures in field settings, including the fact that these approaches are rapid, simple and require limited statistical analyses and human resources. Furthermore, relying on the reports of local people represents an emic perspective that is rare, yet believed by many to be important for cross-cultural mental health work [6, 13, 19, 21, 24, 26]. This approach relies on local terminology for mental health syndromes and incorporates both qualitative and quantitative research methods to investigate the constructs of interest.

By using local terms, interventions can be presented as responding to locally-recognized disorders. Such an approach has the potential to increase engagement and retention in mental health interventions [8]. For example, while the APAI formed the basis for measuring the outcome of a subsequent trial of interventions for the treatment of depression symptoms among Acholi IDP youth, the same qualitative data [9] was also used to select and adapt an evidence-based intervention to address commonly known depression-like problems in this setting [34].

Conclusion

The published literature suggests that the cross-cultural reliability and validity of mental health and psychosocial instruments are rarely assessed in low resource environments. This is partly due to the difficulty (sometimes impossibility) of employing standard assessment methods currently implemented routinely in more resourced environments. This paper describes the adaptation of an approach for assessing validity and reliability under conditions where standard approaches are not feasible. We describe our experience using this approach among a sample of IDP Acholi youth and caregivers, building on previous successful use of the same approach among adults. Based on these experiences, we believe that this approach is a feasible alternative for testing the criterion validity of measures in situations where other approaches are not suitable.

References

Achenbach TM (1991) Manual for the child behavior checklist and 1991 profile. Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont, Burlington

Achenbach TM (1991) Manual for the youth self report and 1991 profile. Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont, Burlington

Achenbach TM, Dumenci L (2001) Advances in empirically based assessment: revised cross-informant syndromes and new DSM-oriented scales for the CBCL, YSR, and TRF: comment on Lengua, Sadowksi, Friedrich, and Fischer (2001). J Consult Clin Psychol 69:699–702

Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT (1987) Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychol Bull 101:213–232

Aidoo M, Harpham T (2001) The explanatory models of mental health amongst low-income women and health care practitioners in Lusaka, Zambia. Health Policy Plan 16:206–213

Bass JK, Bolton PA, Murray LK (2007) Do not forget culture when studying mental health. Lancet 370:918–919

Bass JK, Ryder RW, Lammers CM, Mukaba TN, Bolton PA (2008) Post-partum depression in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo: validation of a concept using a mixed-methods cross-cultural approach. Trop Med Int Health 13:1–9

Bernal G (2006) Intervention development and cultural adaptation research with diverse families. Fam Process 45:143–151

Betancourt TS, Speelman L, Onyango G, Bolton P (2008) A qualitative study of psychosocial problems of war-affected youth in northern Uganda. J Transcult Psychiatry (in press)

Bhagwanjee A, Parekh A, Paruk Z, Petersen I, Subedar H (1998) Prevalence of minor psychiatric disorders in an adult African rural community in South Africa. Psychol Med 28:1137–1147

Bhui K, Craig T, Mohamud S, Warfa N, Stansfeld SA, Thornicroft G, Curtis S, McCrone P (2006) Mental disorders among Somali refugees: developing culturally appropriate measures and assessing socio-cultural risk factors. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 41:400–408

Bolton P (2001) Cross-cultural validity and reliability testing of a standard psychiatric assessment instrument without a gold standard. J Nerv Ment Dis 189:238–242

Bolton P (2001) Local perceptions of the mental health effects of the Rwandan genocide. J Nerv Ment Dis 189:243–248

Bolton P, Bass J, Betancourt T, Speelman L, Onyango G, Clougherty KF, Neugebauer R, Murray L, Verdeli H (2007) Interventions for depression symptoms among adolescent survivors of war and displacement in northern Uganda: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 298:519–527

Bolton P, Wilk CM, Ndogoni L (2004) Assessment of depression prevalence in rural Uganda using symptom and function criteria. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 39:442–447

Cronbach LJ, Meehl PE (1955) Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychol Bull 52:281–302

Derluyn E, Broekaert E, Schuyten G, De Temmerman E (2004) Post-traumatic stress in former Ugandan child soldiers. Lancet 363:861–863

Duhig AM, Renk K, Epstein MK, Phares V (2000) Interparental agreement on internalizing, externalizing, and total behavior problems: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 7:435–453

Geertz C (1973) Interpretation of cultures. Basic Books, New York

Goldstein JM, Simpson JC (1995) Validity: definitions and applications to psychiatric research. In: Tsuang MT, Tohen M, Zahner GEP (eds) Textbook in psychiatric epidemiology. Wiley, New York, pp 229–242

Hollifield M, Warner TD, Nityama L, Krakow B, Jenkins J, Kesler J, Stevenson J, Westermeyer J (2002) Measuring trauma and health status in refugees: a critical review. JAMA 288: 611–621

Kagee A (2004) Do South African former detainees experience post-traumatic stress? Circumventing the demand characteristics of psychological assessment. Transcult Psychiatry 41: 323–336

Kessler RC, Foster CL, Saunders WB, Stang PE (1995) Social consequences of psychiatric disorders, I: educational attainment. Am J Psychiatry 152:1026–1032

Kleinman A (1988) Rethinking psychiatry: from cultural category to personal experience. Free Press, New York

MacMullin C, Loughry M (2004) Investigating psychosocial adjustment of former child soldiers in Sierra Leone and Uganda. J Refug Stud 17:460–472

Mollica R, Lopez Cardoza B, Osofsky HJ, Ager A, Salama P (2004) Mental health in complex emergencies. Lancet 364: 2058–2067

Nubukpo P, Preux PM, Houinato D, Radji A, Grunitzky EK, Avode G, Clement JP (2004) Psychosocial issues in people with epilepsy in Togo and Benin (West Africa) I: anxiety and depression measured using Goldberg’s scale. Epilepsy Behav 5:722–727

Patel V, Simunyu E, Gwanzura F, Lewis G, Mann A (1997) The shona symptom questionnaire: the development of an indigenous measure of common mental disorders in Harare. Acta Psychiatr Scand 95:469–475

Reich W, Earls F (1987) Rules for making psychiatric diagnoses in children on the basis of multiple sources of information: preliminary strategies. J Abnorm Child Psychol 15:601–616

Relief Web (2006) Child soldiers global report: United Nations Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

Seedat S, Nyamai C, Njenga F, Vythilingum B, Stein DJ (2004) Trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress symptoms in urban African schools: survey in Cape Town and Nairobi. Br J Psychiatry 184:169–175

Shrout PE (1995) Reliability. In: Tsuang MT, Tohen M, Zahner GE (eds) Textbook in psychiatric epidemiology. Wiley, New York, pp 213–242

UN OCHA (2007) Forgotten and neglected emergencies: Uganda

Verdeli H, Clougherty K, Onyango G, Lewandowski E, Speelman L, Betancourt TS, Neugebauer R, Stein TR, Bolton P (2008) Group interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed youth in IDP camps in Northern Uganda: adaptation and training. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 17:605–624

Weisz JR, Sigman M, Weiss B, Mosk J (1993) Parent reports of behavioral and emotional problems among children in Kenya, Thailand, and the United States. Child Dev 64:98–109

Zandi T, Havenaar JM, Limburg-Okken AG, van Es H, Sidali S, Kadri N, van den Brink W, Kahn RS (2008) The need for culture sensitive diagnostic procedures: a study among psychotic patients in Morocco. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 43: 244–250

Acknowledgments

A number of talented and dedicated collaborators made this work possible. We are endlessly grateful to all the local research assistants who carried out these interviews in Northern Uganda and to the youth and caregivers who participated in the interviews. We are also grateful to World Vision and War Child Holland for their collaboration and support of this field research. This publication was also made possible by Grant #1K01MH077246-01A2 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Additional thanks go to Seganne Musisi, James Okello, Margarita Alegria and Sidney Atwood for their input and review of study design/and or findings.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Betancourt, T.S., Bass, J., Borisova, I. et al. Assessing local instrument reliability and validity: a field-based example from northern Uganda. Soc Psychiat Epidemiol 44, 685–692 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-008-0475-1

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-008-0475-1