Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Individuals carrying type 2 diabetes risk alleles in TCF7L2 display decreased beta cell levels of T cell factor 7 like-2 (TCF7L2) immunoreactivity, and impaired insulin secretion and beta cell sensitivity to glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). Here, we sought to determine whether selective deletion of Tcf7l2 in mouse pancreas impairs insulin release and glucose homeostasis.

Methods

Pancreas-specific Tcf7l2-null (pTcf7l2) mice were generated by crossing mice carrying conditional knockout alleles of Tcf7l2 (Tcf7l2-flox) with mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the Pdx1 promoter (Pdx1.Cre). Gene expression was assessed by real-time quantitative PCR and beta cell mass by optical projection tomography. Glucose tolerance, insulin secretion from isolated islets, and plasma insulin, glucagon and GLP-1 content were assessed by standard protocols.

Results

From 12 weeks of age, pTcf7l2 mice displayed decreased oral glucose tolerance vs control littermates; from 20 weeks they had glucose intolerance upon administration of glucose by the intraperitoneal route. pTcf7l2 islets displayed impaired insulin secretion in response to 17 (vs 3.0) mmol/l glucose (54.6 ± 4.6%, p < 0.01) or to 17 mmol/l glucose plus 100 nmol/l GLP-1 (44.3 ± 4.9%, p < 0.01) compared with control islets. Glp1r (42 ± 0.08%, p < 0.01) and Ins2 (15.4 ± 4.6%, p < 0.01) expression was significantly lower in pTcf7l2 islets than in controls. Maintained on a high-fat (but not on a normal) diet, pTcf7l2 mice displayed decreased expansion of pancreatic beta cell volume vs control littermates. No differences were observed in plasma insulin, proinsulin, glucagon or GLP-1 concentrations.

Conclusions/interpretation

Selective deletion of Tcf7l2 in the pancreas replicates key aspects of the altered glucose homeostasis in human carriers of TCF7L2 risk alleles, indicating the direct role of this factor in controlling beta cell function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Studies in families [1] and monozygotic twins [2] have provided ample evidence for a hereditary component in type 2 diabetes [3]. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) for type 2 diabetes, first reported in 2007 [4–8], have now revealed nearly 50 loci associated with the disease [9, 10]. Most of the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that are highly associated with type 2 diabetes appear to affect beta cell mass or function [11]. However, assessing the physiological impact of the genetic variations or even identifying the causal gene within a particular genetic locus has been a challenging task. Indeed, most genetic variations are in intronic regions, thus increasing the difficulty of assessing the impact of variants on cellular function. While the introduction into murine models of polymorphic variants using classical ‘knock-in’ is often impractical (and may not lead to clear-cut results, especially if the effect on disease risk is slight, even in man), a key intermediate approach is to examine the effects of loss-of-function of the candidate genes in cell culture systems and in animal models, as indicated in a review [12].

The TCF7L2 gene, located on chromosome 10 in a region tentatively associated with type 2 diabetes in 2003 [13], was directly associated with the disease in Icelandic and other northern European populations by Grant et al [14]. Since then, SNP rs7903146 within intron 4 of TCF7L2 has emerged in GWAS of type 2 diabetes as being most strongly associated with increased risk [4–6, 14]. T cell factor 7 like-2 (TCF7L2) is a member of the T cell factor (TCF) family of transcription factors, which is involved in the control of cell growth and in signalling downstream of wingless-type MMTV integration site family (Wnt) receptors [15]. Activation of the Wnt pathway leads to release of beta catenin from an inhibitory complex and its translocation to the nucleus, where it binds TCF7L2 and other related TCFs [16]. The function of this transcriptional complex is context-dependent, i.e. it may act as a transcriptional activator or as a repressor [16]. TCF7L2 was previously best known through its association with cancer development [17, 18], while the Wnt signalling pathway is essential for proliferation of the pancreatic epithelium [19]. Enhanced Wnt signalling has been shown to lead to islet proliferation [20]. While loss of beta catenin signalling has been shown to lead to pancreatic hypoplasia [21], stabilisation of beta catenin has been shown to result in the formation of large pancreatic tumours [22].

Individuals carrying risk alleles of rs7903146 display lowered insulin secretion [23, 24], impaired insulin processing [25] and decreased sensitivity to the incretin glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) [24–26] compared with controls. It has been reported that TCF7L2 messenger RNA levels in islets from type 2 diabetes patients are elevated [20, 22], whereas TCF7L2 immunoreactivity was depressed [27]. The latter, which suggests a decrease in protein content, was associated with downregulation of GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (or gastric inhibitory peptide) receptor levels, and impaired beta cell function [27]. Interestingly, rs10423928, the SNP in the gastric inhibitory peptide receptor, was also recently found to be associated with impaired oral glucose tolerance, decreased insulin secretion and diminished incretin effect [28].

Studies from our own laboratory and those of others have shown that silencing of Tcf7l2 expression in clonal cell lines [29] and primary islets [29, 30] leads to increased apoptosis [30] and impaired beta cell function [29, 30]. These changes are due, at least partly, to changes in the expression of genes involved in secretory vesicle recruitment to, and fusion with, the plasma membrane [29]. By contrast, overexpression of TCF7L2 exerted no obvious effect on pancreatic islet function [29], although, recently, transgenic mice overexpressing Tcf7l2 were reported to have impaired glucose homeostasis among other physiological anomalies [31]. Gene expression analysis following Tcf7l2 silencing revealed changes in the expression of several genes in mouse pancreatic islets [29], one of which (Glp1r) encodes the GLP-1 receptor [27, 29]. It has also been reported that TCF7L2 may mediate GLP-1-induced beta cell proliferation [32]. Since GLP-1 is implicated in beta cell survival, the increased incidence of apoptosis in TCF7L2-silenced islets [27, 30] and in individuals carrying the variants of TCF7L2 [21] is consistent with lowered GLP-1 signalling [27]. Correspondingly, the diminished insulinotropic effect of GLP-1 in Tcf7l2-silenced islets may be due, at least in part, to the lack of cognate receptors on the cell surface [29].

Given the essentially ubiquitous expression of TCF7L2 across the majority of mammalian tissues (mice with systemic deletion of Tcf7l2 die shortly after birth due to defects in gut development) [33], it has up to now been difficult to establish whether changes at the level of islet cells (including decreased GLP-1 action on beta cells) is the principal (or even an important) contributor to the abnormalities in glucose homeostasis resulting from the inheritance of a risk allele. Indeed, earlier studies [34] suggested a role for TCF7L2 in intestinal L-cells, which are responsible for GLP-1 release, although Pilgaard and colleagues [26] demonstrated that patients carrying the risk T-allele have maintained incretin production, but decreased incretin sensitivity. In the present study, we addressed this question by selectively ablating both alleles of Tcf7l2 in all cells of pancreatic lineage. We hypothesised that loss of TCF7L2 in the pancreas would lead to impaired glucose tolerance if defective beta cell function were central to the increased disease risk. Our results support this hypothesis and point to defective GLP-1 signalling as a cause of the beta cell dysfunction.

Methods

Materials

Reagents were purchased from Sigma (Gillingham, UK) or Invitrogen (Paisley, UK), unless otherwise stated.

Animals

In vivo procedures were approved by the UK Home Office according to the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and performed at the Central Biomedical Service, Imperial College, London, UK. Mice were housed two to five per cage in a pathogen-free facility with a 12 h light–dark cycle and killed by cervical dislocation. Animals had free access to a standard mouse chow diet (Research Diet, New Brunswick, NJ, USA) unless otherwise stated. For high-fat diet treatment, mice were placed on a high-fat diet at 8 weeks of age for 8 weeks (60% [wt/wt] fat content; Research Diet).

Generation and characterisation of pancreas-specific Tcf7l2-null mouse

Mice carrying conditional knockout alleles of Tcf7l2 (Tcf7l2-flox) and in which exon 1 was flanked by LoxP sites (Genoway, Lyon, France) were backcrossed for five generations into a C57BL/6 background. Tcf7l2-flox mice were crossed with mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the Pdx1 promoter (Pdx1.Cre) (a kind gift from D. Melton, Harvard University, Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Cambridge, MA, USA) [31] to generate pancreas-specific Tcf7l2-null (pTcf7l2) mice. To maximise the number of pTcf7l2 mice, Tcf7l2-flox (homozygous)/Pdx1.Cre +/− mice were crossed with Tcf7l2-flox (homozygous)/Pdx1.Cre +/− mice to produce Tcf7l2-flox (homozygous)/Pdx1.Cre +/+ and Tcf7l2-flox (homozygous)/Pdx1.Cre +/− mice, and Tcf7l2-flox (homozygous)/Pdx1.Cre −/− mice as littermate controls. Mice were born at the expected Mendelian ratios with no apparent abnormalities. Genotyping was performed by PCR using DNA from ear biopsies. The ablation of Tcf7l2 gene expression from pancreatic islets was assessed by real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) on islet RNA as described below.

Oral and intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test

Glucose tolerance was assessed by oral and intraperitoneal administration of glucose (1 g/kg body weight). Mice were fasted for 16 h, with free access to water. Glucose tolerance tests were conducted at 09:30 or 09:00 hours for oral and intraperitoneal tests, respectively, on each experimental day.

Measurement of plasma hormones and GLP-1

Blood (200 μl) was removed by cardiac puncture from mice killed by cervical dislocation. Plasma was collected using high speed (2,000 g, 5 min, 4°C) centrifugation in heparin-coated Microvette tubes containing EDTA (Sarstedt, Leicester, UK) with added dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP IV) inhibitor (100 μmol/l) (Millipore, Watford, UK). Plasma insulin, proinsulin and GLP-1 levels from fed mice were assessed by ELISA (insulin, proinsulin: Mercodia, Uppsala, Sweden; GLP-1: Discovery Human Total GLP-1 kit, version 2; MesoScale, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Plasma glucagon from fasted mice was measured by radioimmunoassay (Millipore).

For the measurement of plasma insulin following intraperitoneal injection of glucose, blood (100 μl) was removed from the tail vein at various time points and plasma collected as described above. Plasma insulin was measured as above.

Immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy

Isolated pancreases were fixed in 10% (vol/vol) buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin wax within 24 h of removal. Sections (5 μm) were cut and incubated overnight at 37°C on superfrost slides. Slides were submerged sequentially in Histoclear, followed by decreasing concentrations of industrial methylated spirits for removal of paraffin wax. Permeabilised slices were blotted with primary antibodies, anti-guinea pig insulin (Dako, Ely, UK) and anti-rabbit TCF7L2 (Cell Signaling, Boston, MA, USA), and were visualised with Alexa Fluor 568 donkey anti-guinea pig IgG or with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG. Images were captured on an Axiovert 200 M microscope (Zeiss, Welwyn Garden City, UK) fitted with a ×63 oil objective. Data acquisition was controlled with a spinning disc system (Improvision/Nokigawa, Coventry, UK) running Volocity software (Improvision) [35].

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Primers were designed using Primer Express 3.0 (ABI, Warrington, UK). Specificity for all primers was verified using BLAST (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/) and PCR efficiency standard curves were performed on islet cDNA. RNA from 150 freshly isolated islets per sample was extracted using Trizol and stored at −80°C until required. cDNA conversion was performed using a high-capacity cDNA conversion kit (ABI) after DNAse treatment (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). Real-time PCR plates (ABI) were prepared manually and sealed with optical caps (ABI). Real-time PCR was performed on 25 ng cDNA using HPLC-purified primers on a Fast 7500 device (ABI) running 7500 software (ABI) and with powerSYBR reagent (ABI); ‘no reverse transcription’ control samples were included. Melt curves were performed at the end of each run. For primer sequences, see electronic supplementary material (ESM) Table 1; for PCR amplification efficiency, see ESM Fig. 1.

Insulin secretion assay

The insulin secreted from groups of six pancreatic islets of Langerhans was measured by radioimmunoassay (Millipore) [36, 37].

Optical projection tomography and calculations of relative beta cell mass

Whole pancreatic optical projection tomography (19 μm resolution) was performed as previously described [38, 39].

Statistical analysis

Data are the means ± SEM for the number of observations indicated. Statistical significance and differences between means were assessed by Student’s t test, with Bonferroni’s correction for multiple analyses.

Results

Tcf7l2 gene expression is lowered in islets from pTcf7l2 mice compared with wild-type littermates

To study the roles of Tcf7l2 in endocrine pancreas development and function, we generated pTcf7l2 mice as indicated in the Methods (Fig. 1a). Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated that Pdx1.Cre-mediated excision of exon 1 of Tcf7l2 essentially eliminated immunoreactivity to TCF7L2 protein throughout the pancreas, including islet beta cells (Fig. 1b). qPCR analysis demonstrated that Pdx1.Cre-mediated excision of exon 1 of Tcf7l2 reduced full-length Tcf7l2 mRNA levels in pancreatic islets from pTcf7l2 mice (Fig. 1c) to below the sensitivity of detection (Ct>40; corresponding Ct value for wild-type islets 23.8 ± 0.09) and led to decreased expression of the TCF7L2 target gene, Ccnd1 (Fig. 1c) [40].

Generation of pTcf7l2 mice. (a) Schematic showing wild-type and conditional inactivation (flox’d) of the Tcf7l2 allele with binding sites for primers used for genotyping (dotted lines). Black boxes, exons (exon number in white). (b) Immunohistochemical analysis of pancreases for TCF7L2 and insulin. Scale bar 20 μm. (c) Real-time PCR analysis of gene expression in islets of pTcf7l2 mice (black bars) and wild-type littermate controls (dotted outline or grey bar). Tcf7l2 expression was undetected (UD; Ct>40) in pTcf7l2 mice. ***p < 0.001. Ccnd1, cyclin D1 gene

pTcf7l2 mice display impaired intraperitoneal and oral glucose tolerance

Mice were subjected to intraperitoneal (Fig. 2) or oral (Fig. 3) glucose tolerance tests at 8, 12, 16 and 20 weeks. There was no significant difference in weight gain between pTcf7l2 and control littermates (ESM Fig. 2) on a normal diet at any time point examined, with glucose intolerance apparent when sugar was introduced by intraperitoneal injection at 20 weeks (Fig. 2d). pTcf7L2 mice were also significantly less tolerant to oral glucose than wild-type litter mate control mice, as measured 15 min post gavage (Fig. 3), this difference becoming apparent in younger animals (12 weeks) than was the case for impaired intraperitoneal glucose tolerance (Figs 2b and 3b). Plasma insulin and proinsulin content were not different between fed pTcf7l2 and wild-type littermate controls (ESM Fig. 3). Similar data were obtained from female mice (ESM Figs 4 and 5).

pTcf7l2 mice display normal intraperitoneal glucose tolerance. Male pTcf7l2 mice (grey lines or bars, n = 7) and wild-type littermate controls (black lines or bars, n = 3) were starved for 16 h prior to intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (1 g/kg body weight) at 8 (a, e), 12 (b, f), 16 (c, g) and 20 (d, h) weeks. Time courses (a–d) and AUCs for the entire test period (e–h) are shown. *p < 0.05

pTcf7l2 mice display impaired oral glucose tolerance. Male pTcf7l2 mice (grey lines or bars, n = 11) and wild-type littermate controls (black lines or bars, n = 6) underwent oral glucose tolerance tests at 8 (a, e), 12 (b, f), 16 (c, g) and 20 (d, h) weeks. Time courses (a–d) and AUCs for the entire test period (e–h) are shown. *p < 0.05

Islets from pTcf7l2 mice do not release insulin in response to GLP-1 stimulation

Islets isolated from 20-week-old pTcf7l2 mice displayed impaired glucose- and GLP-1-stimulated insulin secretion (54.6 ± 4.6% and 44.3 ± 4.9% lower than from control islets cultured at 16.7 mmol/l glucose or at 16.7 mmol/l glucose plus 100 nmol/l GLP-1, respectively) (Fig. 4a).

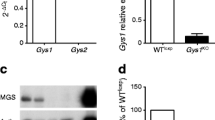

pTcf7l2 islets display lowered glucose- and GLP-1-stimulated insulin secretion. (a) Batches of six size-matched islets, isolated from 20-week-old mice and cultured for 10 days in 11 mmol/l glucose and then for 1 h at 3 mmol/l glucose, were incubated for 20 min at the indicated concentrations of glucose and GLP-1, after which time the supernatant fraction was collected. Islets were lysed in acid ethanol. Insulin in the islet lysate and supernatant fractions was assayed in duplicate by radioimmunoassay. Black bars, wild-type littermate controls ; grey bars, pTcf7l2 mice. (b) qPCR results for islets from pTcf7l2 mice (grey bars) and wild-type littermate controls (black bars). Data are from three separate islet preparations, with measurements in duplicate. (c) Plasma GLP-1 concentrations were measured in pTcf7l2 mice (grey bars) and wild-type littermate controls (black bars). (d) Plasma insulin content was measured in 20-week-old pTcf7l2 mice (grey line) and control littermates (black line), following glucose administration by intraperitoneal injection. (e) Plasma glucagon content was measured in 20-week-old pTcf7l2 mice (grey bar) and control littermates (black bar) following a 16 h fast. Data (c–e) are from at least four mice per genotype; *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01

We have previously shown that silencing of Tcf7l2 in mouse islets using a small interfering RNA (siRNA) against Tcf7l2 led to decreased expression of Ins2 and Munc18 (also known as Stxbp2) and increased expression of Stx1a [29]. In qPCR, pTcf7l2 islets displayed markedly decreased expression of Ins2 and Glp1r (Fig. 4b), namely by 15.4 ± 4.6% and 42 ± 0.08%, respectively, vs islets from littermate controls. By contrast, expression of the glucagon, Stx1a and Munc18-1 (also known as Stxbp1) genes was not altered in pTcf7l2 mouse islets vs controls (data not shown).

No genotype-specific differences in plasma GLP-1 content were apparent when examined in mice that had free access to food (Fig. 4c), indicating that oral glucose intolerance was unlikely to be due to changes in GLP-1 release from intestinal L-cells. In contrast, plasma insulin content was significantly lower in 20-week-old pTcf7l2 mice than in controls after the intraperitoneal injection of glucose (Fig. 4d); however, there was no apparent difference in fasted plasma glucagon content (Fig. 4e) between pTcf7l2 and control mice.

Beta cell mass is unchanged in pTcf7l2 mice on a normal chow diet

To determine whether the abnormal glucose tolerance described above might reflect altered pancreatic beta cell mass, the latter was determined by optical projection tomography [38, 39] (Fig. 5). This technique allows the distribution and total volume of insulin-positive areas to be assessed in pancreases rendered permeable to antibodies [38, 39]. No differences were apparent in the distribution, size and number of insulin-positive cells between pancreases from pTcf7l2 mice and wild-type littermate controls (Fig. 5a, b; ESM Videos 1 and 2 for wild-type mice and pTcf7l2 mice, respectively). Likewise, there were no significant differences in relative beta cell volume (1.66 ± 0.27 vs 1.89 ± 0.32 for pTcf7l2 and control mice, respectively) (Fig. 5c) or total pancreatic volume (Fig. 5d) between pTcf7l2 mice and wild-type litter mate controls (n = 4 mice per genotype).

pTcf7l2 mice on a normal diet have normal pancreas and beta cell volume. (a) Representative images from optical projection tomography of 16-week-old pTcf7l2 mice and wild-type (WT) littermate controls. Red, insulin staining; scale bar 650 μm. (b) Distribution of islet size in pancreases of pTcf7l2 mice (black bars) and wild-type littermate controls (grey bars). (c) Relative beta cell volume and (d) total pancreatic volume of pTcf7l2 mice and wild-type littermate controls. Cell and tissue volumes were obtained using Volocity (Improvision) software. Data were obtained from four mice per genotype

Impaired tolerance to intraperitoneal glucose in pTcf7l2 mice fed a high-fat diet

Maintenance of pTcf7l2 mice on a high-fat diet of 8 weeks duration from 8 weeks of age led to impaired intraperitoneal glucose tolerance vs control mice (Fig. 6a), which occurred 4 weeks earlier than in mice on a normal chow diet (Fig. 2). Both pTcf7l2 and control mice developed lowered insulin sensitivity following 8 weeks on a high-fat diet (Fig. 6b), compared with mice on a normal chow diet (Fig. 6c).

pTcf7l2 mice on a high-fat diet display decreased insulin sensitivity and impaired glucose tolerance. (a) Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance in pTcf7l2 mice (grey symbols) and control littermates (black symbols) following 8 weeks on a high-fat diet. (b) Insulin sensitivity after an intraperitoneal injection of insulin in 16-week-old pTcf7l2 mice (grey symbols) and control littermates (black symbols) following 8 weeks on a high-fat diet or (c) in the same mouse groups maintained on a normal diet. Data are from at least six mice per genotype; *p < 0.05

Impaired beta cell mass expansion in pTcf7l2 mice on a high-fat diet

As TCF7L2 is associated with cell proliferation [16, 17, 33], we next determined whether pTcf7l2 mice displayed impaired beta cell mass when fed a high-fat diet (Fig. 7; ESM videos 3 and 4 for wild-type mice and pTcf7l2 mice, respectively). Supporting this view, pTcf7l2 mouse pancreases had decreased numbers of islets at the extremes of the size spectrum (Fig. 7b), indicating potential abnormalities in the generation of new beta cells and in the proliferation of beta cells in pTcf7l2 mice. Correspondingly, there was a decrease in total beta cell volume in pTcf7l2 pancreases vs control (1.70 ± 0.25% vs 2.53 ± 0.28%) (Fig. 7c), but no significant difference in total pancreatic volume (Fig. 7d).

pTcf7l2 mice on a high-fat diet display impaired beta cell expansion. (a) Representative images from optical projection tomography of 16-week-old pTcf7l2 mice (n = 3) and wild-type (WT) littermate controls (n = 2) following 8 weeks on a high-fat diet. Red, insulin staining; scale bar 650 μm. (b) Distribution of islet size in pancreases of pTcf7l2 mice (grey bars) and wild-type littermate controls (black bars); expanded view of section between dotted line in larger graph in inset. (c) Relative beta cell volume and (d) total pancreatic volume of pTcf7l2 mice and wild-type littermate controls. Cell and tissue volumes were obtained using Volocity software (Improvision). *p < 0.05

Discussion

The principal aim of the present study was to determine whether selective deletion of Tcf7l2 in the pancreas replicates the essential metabolic features associated with inheritance of TCF7L2 risk alleles, namely impaired GLP-1-induced, but normal intravenous glucose-induced insulin secretion [26, 41]. To this end we used a Pdx1.Cre deleter strain (ESM Fig. 6) [42] to effect deletion in the pancreas, allowing us: (1) to minimise the risks of deletion in the brain, which occur with the more commonly used Ins2.Cre deleter mice [43]; and (2) to capture the potential effects of Tcf7l2 deletion early in pancreatic development.

Consistent with earlier in vitro studies on isolated islets from mice [29] and humans [30] in which Tcf7l2/TCF7L2 gene expression was decreased using siRNA-mediated gene silencing, islets from pTcf7l2 mice displayed abnormalities in glucose- and GLP-1-induced insulin secretion (Fig. 4a). Interestingly, defects in intraperitoneal glucose tolerance were absent in mice <16 weeks of age (Fig. 2) and mild even in older animals. By contrast, clear abnormalities in oral glucose tolerance were apparent in pTcf7l2 mice from 12 weeks (Fig. 3). Fasted glucose levels (Figs 2, 3 and 6c) were unchanged in pTcf7l2 mice compared with control littermates, suggesting there were no profound effects on glucagon release from alpha cells, despite the expected deletion of Tcf7l2 from this cell type, too, as well as a previous report suggesting that carriers of the risk T-allele may have impaired alpha cell function [26]. Insulin sensitivity (Fig. 6c) and plasma glucagon levels (Fig. 4e) were unaltered in pTcf7l2 mice on a normal chow diet. Likewise, no differences in body mass were observed between pTcf7l2 mice and wild-type littermates under any conditions tested (ESM Fig. 2). Plasma GLP-1 (Fig. 4c), insulin and proinsulin (ESM Fig. 3) contents in pTcf7l2 mice were not different from control wild-type littermates, but pTcf7l2 islets had decreased Glp1r expression (Fig. 4b), indicating that the defective oral glucose tolerance may have been due to a decrease in GLP-1 signalling in pTcf7l2 islets.

pTc7l2 mice (ESM Fig. 2) and Glp1r-null mice [44] have normal body weight. However, unlike the latter, which have disturbed glucose tolerance irrespective of whether glucose is administered orally or intraperitoneally [44], pTcf7l2 mice had milder glucose intolerance, which was more pronounced with age (Figs 2 and 3) or following a high-fat diet (Fig. 6a).

It has previously been reported that islets from Glp1r-null mice exhibit normal glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, although the augmentation of insulin secretion by GLP-1 is impaired [45]. pTcf7l2 islets exhibited lowered glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (Fig. 4a), while 20-week-old mice had lower plasma insulin levels in response to an intraperitoneal glucose challenge (Fig. 4d). We have previously reported that the expression of Stx1a and Munc18-1 genes was affected in mouse islets when Tcf7l2 expression was silenced using an siRNA against Tcf7l2 [29]. Interestingly, the expression of these genes was not affected in pTcf7l2 islets (data not shown). This discrepancy between data from siRNA-mediated gene silencing in culture systems vs that from a tissue-specific knockout mouse may reflect differences between the effects of acute and chronic downregulation of Tcf7l2 gene expression and/or the existence of compensatory mechanisms, which are lacking in culture systems. This discrepancy therefore merits further investigation.

pTcf7l2 mice that were exposed at 16 weeks of age to 8 weeks of a high-fat diet displayed decreased beta cell mass in comparison to littermate controls (Fig. 7) as assessed by optical projection tomography following 3-dimensional reconstruction of whole mouse pancreases. These data parallel those of Maedler and colleagues in rats fed a high-fat diet [46], where a correlation between TCF7L2 abundance and beta cell regeneration from pancreatic ductal cells was observed, possibly reflecting the inability of beta cells to proliferate or regenerate from progenitor cells in the absence of functional TCF7L2. The decreased expression of Ccnd1 (Fig. 1c) in islets of Langerhans extracted from 20-week-old mice may also have contributed towards the lack of cell proliferation.

Patients carrying the risk SNP at rs7903146 display alterations in proinsulin/insulin ratios, which suggest that the glucose intolerance observed in these patients may be due to decreased levels of circulating mature insulin [23]. In contrast with these findings in man, plasma proinsulin levels and insulin content in pTcf7l2 mice were not different from wild-type littermate controls (ESM Fig. 3). However, glucose intolerance was more pronounced when glucose was administered orally to mice on a normal diet, indicating that the primary defect in pTcf7l2 mice could be lack of response to GLP-1, followed by impaired beta cell expansion in response to stress, e.g. high-fat diet.

It is currently unclear how the SNP at rs7903146 affects TCF7L2 gene expression and protein levels. Given that the SNP is associated with increased TCF7L2 mRNA levels in type 2 diabetic patients [24, 27], one hypothesis is that increased abundance of TCF7L2 may be associated with the development of type 2 diabetes. Savic and colleagues [31] have proposed that the intragenic region associated with type 2 diabetes may act as an enhancer region and lead to increased TCF7L2 abundance. Using BACS transgenic mice carrying the protective C-allele of rs7903146, the same group demonstrated that this intragenic region has enhancer activity in islets of neonatal mice, but not in adult islets [31]. Transgenic mice containing three copies of full-length Tcf7l2 cDNA driven by the enhancer region had increased Tcf7l2 expression and impaired glucose tolerance, while deletion of exon 11 of Tcf7l2 led to improved glucose tolerance in heterozygote mice [31]. However, as the modification of Tcf7l2 expression was induced in all mouse tissues, it is unclear whether these effects were due to effects on pancreatic islet function or on extra-pancreatic tissue, or to a combination of both. The data are hard to interpret in the context of pancreatic islet function, as enhancer activity was not detected in adult islets and expression of Tcf7l2 was not assessed in islets of Langerhans from the multimeric enhance-driven Tcf7l2 transgenic mouse [31]. In addition, the effect of the type 2 diabetes risk-conferring variant T-allele on enhancer function was not addressed [31]. In contrast, Gaulton and colleagues [47] demonstrated that heterozygote T-allele carriers have more open chromatin, which is associated with the increased enhancer activity conferred by the risk allele. This is in line with the observation that the risk T-allele is associated with increased TCF7L2 transcripts in islets. However, the authors also state that the allele-specific changes could impact on different genomic regulatory functions, including transcriptional promoter usage or splicing [47], and could, for example, lead to increased expression of alternative transcripts with dominant negative function.

As TCF7L2 protein content in type 2 diabetic islets was shown to be lower than in control islets, despite higher TCF7L2 message levels, another hypothesis is that the polymorphism, which is located in an intron, may lead to the increased expression of alternative transcripts of TCF7L2 through the upregulation of naturally occurring alternative transcripts [48–52]. These may then conceivably act as dominant negative repressors of TCF7L2. Alternative transcripts of TCF7L2 are expressed in a tissue-specific manner [25]. Data from Le Bacquer and colleagues [53] also indicate that expression of alternative transcripts that do not contain exons 13, 14, 15 and 16 could lead to increased beta cell apoptosis, while expression of transcripts containing exon 13 leads to improved beta cell function and survival. Recently, we showed that a truncated transcript of TCF7L2 that is generated by an alternative polyadenylation site in intron 4 within the region associated with type 2 diabetes risk is expressed in pancreatic beta cells and can act as a dominant negative regulator of TCF7L2 function by competitive binding to beta catenin [51], thus possibly leading to downregulation of Wnt signalling and beta cell proliferation, as observed in pTcf7l2 mice on a high-fat diet. It is currently unclear whether the expression of this transcript or any of the other alternative transcripts with potential dominant negative activity is altered by the presence of the risk T-allele of rs7903146.

While the Pdx1.Cre strain used here is likely to result in deletion in other (non-beta) cell types [43], we observed no changes in circulating levels of glucagon or GLP-1, which might have contributed to the phenotype, or in insulin sensitivity. Moreover, our preliminary data (not shown), obtained using a more beta cell-selective Ins1.Cre deleter strain provided by J. Ferrer (Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Spain) and B. Thorens (University of Lausanne, Switzerland), also revealed deficiencies in insulin secretion and glucose tolerance, suggesting that TCF7L2 plays a critical and cell autonomous role in the beta cell compartment.

In summary, the present study demonstrates that the elimination of Tcf7l2 function selectively in the pancreas is sufficient to replicate many of the key features observed in T-allele carriers of TCF7L2, which comprise ∼50% of the individuals in many human populations. Thus, Tcf7l2 appears to be required in the beta cell for the expansion of these cells under conditions of insulin resistance and for the normal function of the mature beta cell. An action on both of these factors thus results in a loss of functional beta cell mass. Strategies based on enhancing the function of TCF7L2 in the endocrine pancreas could lead to new ways of treating diabetes.

Abbreviations

- GLP-1:

-

Glucagon-like peptide 1

- GWAS:

-

Genome-wide association studies

- Pdx1.Cre :

-

Mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the Pdx1 promoter

- pTcf7l2 :

-

Pancreas-specific Tcf7l2-null

- qPCR:

-

Real-time quantitative PCR

- siRNA:

-

Small interfering RNA

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- TCF:

-

T cell factor

- TCF7L2:

-

T cell factor 7 like-2

- Tcf7l2-flox:

-

Mice carrying conditional knockout alleles of Tcf7l2

- Wnt:

-

Wingless-type MMTV integration site family

References

Pierce M, Keen H, Bradley C (1995) Risk of diabetes in offspring of parents with non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Diabet Med 12:6–13

Newman B, Selby JV, King MC, Slemenda C, Fabsitz R, Friedman GD (1987) Concordance for type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus in male twins. Diabetologia 30:763–768

Barroso I (2005) Genetics of type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med 22:517–535

Scott LJ, Mohlke KL, Bonnycastle LL et al (2007) A genome-wide association study of type 2 diabetes in Finns detects multiple susceptibility variants. Science 316:1341–1345

Sladek R, Rocheleau G, Rung J et al (2007) A genome-wide association study identifies novel risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Nature 445:881–885

Zeggini E, Weedon MN, Lindgren CM et al (2007) Replication of genome-wide association signals in UK samples reveals risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Science 316:1336–1341

Saxena R, Voight BF, Lyssenko V et al (2007) Genome-wide association analysis identifies loci for type 2 diabetes and triglyceride levels. Science 316:1331–1336

Steinthorsdottir V, Thorleifsson G, Reynisdottir I et al (2007) A variant in CDKAL1 influences insulin response and risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet 39:770–775

McCarthy MI (2010) Genomics, type 2 diabetes, and obesity. N Engl J Med 363:2339–2350

Travers ME, McCarthy MI (2011) Type 2 diabetes and obesity: genomics and the clinic. Hum Genet 130:41–58

Voight BF, Scott LJ, Steinthorsdottir V et al (2010) Twelve type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci identified through large-scale association analysis. Nat Genet 42:579–589

Cox RD, Church CD (2011) Mouse models and the interpretation of human GWAS in type 2 diabetes and obesity. Dis Model Mech 4:155–164

Reynisdottir I, Thorleifsson G, Benediktsson R et al (2003) Localization of a susceptibility gene for type 2 diabetes to chromosome 5q34-q35.2. Am J Hum Genet 73:323–335

Grant SF, Thorleifsson G, Reynisdottir I et al (2006) Variant of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) gene confers risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet 38:320–323

Jin T, Liu L (2008) The Wnt signaling pathway effector TCF7L2 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mol Endocrinol 22:2383–2392

Reya T, Clevers H (2005) Wnt signalling in stem cells and cancer. Nature 434:843–850

Roose J, Clevers H (1999) TCF transcription factors: molecular switches in carcinogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1424:M23–M37

Saadeddin A, Babaei-Jadidi R, Spencer-Dene B, Nateri AS (2009) The links between transcription, beta-catenin/JNK signaling, and carcinogenesis. Mol Cancer Res 7:1189–1196

Papadopoulou S, Edlund H (2005) Attenuated Wnt signaling perturbs pancreatic growth but not pancreatic function. Diabetes 54:2844–2851

Rulifson IC, Karnik SK, Heiser PW et al (2007) Wnt signaling regulates pancreatic beta cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:6247–6252

Wells JM, Esni F, Boivin GP et al (2007) Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is required for development of the exocrine pancreas. BMC Dev Biol 7:4

Heiser PW, Lau J, Taketo MM, Herrera PL, Hebrok M (2006) Stabilization of beta-catenin impacts pancreas growth. Development 133:2023–2032

Loos RJ, Franks PW, Francis RW et al (2007) TCF7L2 polymorphisms modulate proinsulin levels and beta-cell function in a British Europid population. Diabetes 56:1943–1947

Lyssenko V, Lupi R, Marchetti P et al (2007) Mechanisms by which common variants in the TCF7L2 gene increase risk of type 2 diabetes. J Clin Invest 117:2155–2163

Villareal DT, Robertson H, Bell GI et al (2010) TCF7L2 variant rs7903146 affects the risk of type 2 diabetes by modulating incretin action. Diabetes 59:479–485

Pilgaard K, Jensen CB, Schou JH et al (2009) The T allele of rs7903146 TCF7L2 is associated with impaired insulinotropic action of incretin hormones, reduced 24 h profiles of plasma insulin and glucagon, and increased hepatic glucose production in young healthy men. Diabetologia 52:1298–1307

Shu L, Matveyenko AV, Kerr-Conte J, Cho JH, McIntosh CH, Maedler K (2009) Decreased TCF7L2 protein levels in type 2 diabetes mellitus correlate with downregulation of GIP- and GLP-1 receptors and impaired beta-cell function. Hum Mol Genet 18:2388–2399

Saxena R, Hivert MF, Langenberg C et al (2010) Genetic variation in GIPR influences the glucose and insulin responses to an oral glucose challenge. Nat Genet 42:142–148

da Silva XG, Loder MK, McDonald A et al (2009) TCF7L2 regulates late events in insulin secretion from pancreatic islet beta-cells. Diabetes 58:894–905

Shu L, Sauter NS, Schulthess FT, Matveyenko AV, Oberholzer J, Maedler K (2008) Transcription factor 7-like 2 regulates beta-cell survival and function in human pancreatic islets. Diabetes 57:645–653

Savic D, Ye H, Aneas I, Park SY, Bell GI, Nobrega MA (2011) Alterations in TCF7L2 expression define its role as a key regulator of glucose metabolism. Genome Res 21:1417–1425

Liu Z, Habener JF (2008) Glucagon-like peptide-1 activation of TCF7L2-dependent Wnt signaling enhances pancreatic beta cell proliferation. J Biol Chem 283:8723–8735

Korinek V, Barker N, Moerer P et al (1998) Depletion of epithelial stem-cell compartments in the small intestine of mice lacking Tcf-4. Nat Genet 19:379–383

Yi F, Brubaker PL, Jin T (2005) TCF-4 mediates cell type-specific regulation of proglucagon gene expression by beta-catenin and glycogen synthase kinase-3beta. J Biol Chem 280:1457–1464

Meur G, Qian Q, da Silva XG et al (2011) Nucleo-cytosolic shuttling of FoxO1 directly regulates mouse Ins2 but not Ins1 gene expression in pancreatic beta cells (MIN6). J Biol Chem 286:13647–13656

Ainscow EK, Zhao C, Rutter GA (2000) Acute overexpression of lactate dehydrogenase-A perturbs beta-cell mitochondrial metabolism and insulin secretion. Diabetes 49:1149–1155

da Silva XG, Leclerc I, Varadi A, Tsuboi T, Moule SK, Rutter GA (2003) Role for AMP-activated protein kinase in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and preproinsulin gene expression. Biochem J 371:761–774

Alanentalo T, Asayesh A, Morrison H et al (2007) Tomographic molecular imaging and 3D quantification within adult mouse organs. Nat Methods 4:31–33

Sun G, Tarasov AI, McGinty J et al (2010) Ablation of AMP-activated protein kinase alpha1 and alpha2 from mouse pancreatic beta cells and RIP2.Cre neurons suppresses insulin release in vivo. Diabetologia 53:924–936

Rajabi H, Ahmad R, Jin C et al (2012) MUC1-C oncoprotein induces TCF7L2 activation and promotes cyclin D1 expression in human breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem 287:10703–10713

Schafer SA, Tschritter O, Machicao F et al (2007) Impaired glucagon-like peptide-1-induced insulin secretion in carriers of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) gene polymorphisms. Diabetologia 50:2443–2450

Gu G, Dubauskaite J, Melton DA (2002) Direct evidence for the pancreatic lineage: NGN3+ cells are islet progenitors and are distinct from duct progenitors. Development 129:2447–2457

Wicksteed B, Brissova M, Yan W et al (2010) Conditional gene targeting in mouse pancreatic ss-cells: analysis of ectopic Cre transgene expression in the brain. Diabetes 59:3090–3098

Scrocchi LA, Brown TJ, MaClusky N et al (1996) Glucose intolerance but normal satiety in mice with a null mutation in the glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor gene. Nat Med 2:1254–1258

Flamez D, van Breusegem A, Scrocchi LA et al (1998) Mouse pancreatic beta-cells exhibit preserved glucose competence after disruption of the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor gene. Diabetes 47:646–652

Maedler K, Kerr-Conte J, Shu L (2011) TCF7L2 plays a role in the beta cell regeneration. Diabetologia S 1:407 (Abstract)

Gaulton KJ, Nammo T, Pasquali L et al (2010) A map of open chromatin in human pancreatic islets. Nat Genet 42:255–259

Duval A, Rolland S, Tubacher E, Bui H, Thomas G, Hamelin R (2000) The human T cell transcription factor-4 gene: structure, extensive characterization of alternative splicings, and mutational analysis in colorectal cancer cell lines. Cancer Res 60:3872–3879

Mondal AK, Das SK, Baldini G et al (2010) Genotype and tissue-specific effects on alternative splicing of the transcription factor 7-like 2 gene in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:1450–1457

Osmark P, Hansson O, Jonsson A, Ronn T, Groop L, Renstrom E (2009) Unique splicing pattern of the TCF7L2 gene in human pancreatic islets. Diabetologia 52:850–854

Locke JM, da Silva XG, Rutter GA, Harries LW (2011) An alternative polyadenylation signal in TCF7L2 generates isoforms that inhibit T cell factor/lymphoid-enhancer factor (TCF/LEF)-dependent target genes. Diabetologia 54:3078–3082

Prokunina-Olsson L, Welch C, Hansson O et al (2009) Tissue-specific alternative splicing of TCF7L2. Hum Mol Genet 18:3795–3804

Le Bacquer O, Shu L, Marchand M et al (2011) TCF7L2 splice variants have distinct effects on beta-cell turnover and function. Hum Mol Genet 20:1906–1915

Acknowledgements

We thank E. Bellomo, D. Hodson and S. Vakhshouri (Section of Cell Biology, Division of Diabetes, Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Medicine, Imperial College London) for technical assistance.

Funding

The research leading to these results was funded by the EFSD (G. da Silva Xavier), the Wellcome Trust (Programme Grant 081958/Z/07/Z and Senior Investigator award to G.A. Rutter), the Royal Society (Royal Society Wolfson Award to G.A. Rutter) and the Medical Research Council (MRC), UK (G0401641 and G0700342 to G.A. Rutter). GLP-1 assays were performed with the support of the MRC Centre for Obesity and Related Metabolic Diseases (MRC CORD), Cambridge, UK.

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Contribution statement

All the authors contributed to (1) the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of data; and (2) the drafting of the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content; and (3) all authors approved the final version to be published. GDSX generated and genotyped the conditional knockout mice, and performed the following: oral and intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test; gene expression analysis; insulin secretion assays on pancreatic islets; optical projection tomography analysis of pancreases; and the isolation, culture and analysis of pancreatic embryonic explants. AM isolated islets and performed gene expression analysis. SG performed oral gavage and LC, JAM and PMF performed optical projection tomography.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Electronic supplementary materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM Fig. 1

Efficiency of amplification of real-time PCR. Validation of real-time PCR primers for Tcf7l2, Ins2, Glp1r, Ccnd1, cyclophilin genes using 25, 50 and 100 ng of islet RNA. Black rhombus, square, triangle and round markers for Ct values for primers for Tcf7l2, Ins2, Glp1r, Ccnd1 genes, respectively. Grey round marker for Ct values for primers for cyclophilin. r 2 value for all fitted lines >0.98. (PDF 55.8 kb)

ESM Fig. 2

pTcf7l2 mice display normal body weight. Male pTcf7l2 mice (grey bars; n = 7) and wild-type littermate control (black bars; n = 3) were starved for 16 h and weighed prior to intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test. (PDF 35.8 kb)

ESM Fig. 3

pTcf7l2 null mice display normal plasma insulin and proinsulin content. Plasma proinsulin (a) and insulin (b) content were measured by ELISA from pTcf7l2 (grey bars; n = 4) and wild-type littermate control mice (black bars; n = 3). c) % of plasma proinsulin vs insulin. (PDF 44.1 kb)

ESM Fig. 4

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test on female pTcf7l2 mice. Female pTcf7l2 mice ( grey lines or bars, n = 6) and wild-type littermate control (black lines or bars, n = 4) were starved for 16 h prior to intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (1 g/kg) at 8 (a, e), 12 (b, f), 16 (c, g), and 20 (d, h) weeks. Time course (a, b, c, d) and area under the curve for the entire test period (e, f, g, h) are shown. *, p < 0.05. (PDF 79.0 kb)

ESM Fig. 5

Oral glucose tolerance test on female pTcf7l2 mice. Female pTcf7l2 mice (grey lines or bars, n = 6) and wild-type littermate control (black lines or bars, n = 4) were subjected to oral glucose tolerance test at 8 (a, e), 12 (b, f), 16 (c, g), and 20 (d, h) weeks. Time course (a, b, c, d) and area under the curve for the entire test period (e, f, g, h) are shown. *, p < 0.05. (PDF 70.6 kb)

ESM Fig. 6

Tcf7l2−/−/PDX-cre+ and Tcf7l2−/−/PDX-cre− mouse have normal intraperitoneal glucose tolerance. Male Tcf7l2 −/−/PDX-cre+ mice (grey lines, n = 6) and wild-type littermate control (Tcf7l2 −/−/PDX-cre+ mice; black lines, n = 6) were starved for 16 h prior to intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (1 g/kg) at 8 (a), 12 (b), 16 (c), and 20 (d) weeks. (PDF 78.3 kb)

ESM Table 1

(PDF 78.3 kb)

ESM Video 1

OPT of wild-type pancreas from mice on normal diet. (MOV 492 kb)

ESM Video 2

OPT of pTcf7l2 pancreas from mice on normal diet. (MOV 517 kb)

ESM Video 3

OPT of wild-type pancreas from mice on high fat diet. (MOV 807 kb)

ESM Video 4

OPT of pTcf7l2 pancreas from mice on high fat diet. (MOV 2,593 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

da Silva Xavier, G., Mondragon, A., Sun, G. et al. Abnormal glucose tolerance and insulin secretion in pancreas-specific Tcf7l2-null mice. Diabetologia 55, 2667–2676 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-012-2600-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-012-2600-7