Abstract

Objectives

Unemployment is a major determinant of health. We investigate whether health inequalities with regards to employment status have changed in Germany.

Methods

We used longitudinal data for the years 1994–2008 from a representative panel study (GSOEP). The sample consisted of respondents aged 30–59 years (15 waves, 21,329 persons, 129,526 observations). We analyzed trends and determinants of self-rated health status by employment status using logistic regression and fixed-effects logistic panel models.

Results

Health inequalities by employment status increased significantly by 72% in men and by 16% in women after controlling covariates. The trends were partly mediated by consequences of unemployment such as income loss, income poverty, life satisfaction and economic sorrows. Using regression models for panel data we confirmed that the observed increases in health inequalities at the population level also exist at the individual level.

Discussion

Altogether, our findings indicate that health inequalities with regards to employment status increased among men between 1994 and 2008. This observation is in line with increasing income inequalities in Germany and with increasing health inequalities in other European countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Social inequalities in health have been widely documented and studied in many countries (Bartley et al. 1998; Mackenbach 2006). Increasing research has recently focused on examining systematic differences in the magnitude of inequalities between regions, countries or groups of countries (Mackenbach et al. 2008; Bambra and Eikemo 2009; Eikemo et al. 2008b) and trends in health inequalities within countries (Kunst et al. 2005; Avendano et al. 2005; Mackenbach et al. 2003; Lahelma et al. 2002; Dalstra et al. 2002; Mazzuco and Suhrcke 2010). As of currently, research has shown that health inequalities in Europe have increased in some but not all countries and that there is considerable variation in the corresponding trends by gender, health or socio-economic indicator and measure of inequality. In this study, we analyse changes in health inequalities with regards to employment status in Germany since 1994.

Health inequalities in relation to employment status have been studied far less frequently than in relation to income or education. Nonetheless, unemployed men and women constitute a population group that is more clearly definable and, arguably, simplier to target through policy measures than the more heterogeneous group of “the poor”. Unemployment is associated with increased mortality, worse physical and mental health and more frequent use of health services (Bartley 1994; Mathers and Schofield 1998). Unhealthy lifestyle behaviours are also more common among the unemployed. Available evidence suggests that the association of unemployment and health is mediated by manifest (e.g. loss of income, material deprivation) and latent consequences (e.g. status deprivation, loss of time structure) (Bartley 1994; Mathers and Schofield 1998; Creed and Macintyre 2001). Additionally, a changing association between unemployment and health during economic change and systematic differences in the effects of employment status on health between countries has been recently described (Béland et al. 2002; Ahs and Westerling 2006; Arber and Lahelma 1993; Bambra and Eikemo 2009).

Within the last two decades, Germany has gone through enormous social change. After the re-unification of the two German states in 1991, the federal government was faced with rising debts, slow economic growth, rising unemployment rates and an ageing population. In tackling these challenges, the various federal governments conducted far reaching reforms of the German welfare system during the last two decades (Alber 2003; Fleckenstein 2008; Zimmermann 2005). During the 1990s, benefits for long and short-term unemployment were reduced several times and stricter rules and fines for the rejection of job offers as well as fewer opportunities for early retirement were implemented. Especially with the Hartz legislations from 2003 to 2005, the ‘frozen welfare state’ of Germany critically departed from its conservative path to a more market-oriented approach (Fleckenstein 2008). As a result, job loss since 1990 became an increasingly serious source of anxiety among Germans as overall poverty rates increased considerably with the worst overall increases in unemployment (Giesecke and Groß 2005; OECD 2008a). Given this particular political, economic and social context in Germany, monitoring changes in the magnitude of health inequalities between the employed and the unemployed within the last two decades is especially relevant, and can further provide insight on relation of social change and health inequalities in general.

We used longitudinal data from the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (GSOEP) to analyze trends in health inequalities between the employed and unemployed in Germany. In the present study, we first examine whether there were increasing health inequalities between the employed and the unemployed in Germany between 1994 and 2008. During the time of this study, this timeframe was the longest for which representative panel data on health and unemployment were available after the German reunification. We then investigate whether the trends can be attributed to changing material and psychosocial consequences of unemployment. The analysis of mediating factors allow us to draw implications for social policy—in particular, whether changes in health inequalities are mediated solely by income loss or also by rising perceptions of insecurity among the unemployed.

Methods

The GSOEP is a longitudinal household panel study conducted from 1984 onwards in West Germany and from 1991 in the former GDR, or East Germany (Wagner et al. 2007). In each participating household, all persons aged 18 years and older fill out a personal questionnaire every year, typically in spring. The stability of the sample is well beyond 90 percent for all subsamples and the proportion of personally interviewed household members is about 94% (TNS Infratest and SOEP-Group 2006). The study covers a wide range of socioeconomic indicators and a small number of health outcomes. The GSOEP population is regularly updated with new survey samples to reflect changes in the German population. The data has previously been used to analyse socioeconomic inequalities in health (Frijters et al. 2005; Nolte and McKee 2004; Rodriguez 2002). GSOEP is approved to be in accordance with the high standards for lawful data protection in the Federal Republic of Germany. We used all waves of GSOEP from 1994 to 2008. To facilitate the comparability over time, the waves were weighted with respect to age composition, gender and state of residence to match the German population as of December 31, 2004. The authors signed a contract with the data holders and are allowed to use and publish the data for scientific purposes.

Key demographic information on the study population is shown in Table 1. We restricted the analysis to men and women aged 30–59 years who were either employed or unemployed (94.5% of male and 76.5% of female respondents aged 30–59 years), while those in educational institutions or out of the labour force were excluded from the study. Overall, 21,329 respondents were observed 129,526 times between 1994 and 2008. The average number of observations per respondent was 9.0 during the observational period. The average age of the respondents was 43.6 years and 92.8% of the study sample had no missing values in any indicator measured.

We used the general self-rated health status (SRH) of the participants as our outcome measure. SRH is widely regarded as a good proxy for measuring general health and has been used previously to analyse trends and variations in health inequalities (Kunst et al. 2005; Eikemo et al. 2008a; Mackenbach et al. 2008). Cross-cultural differences make it difficult to compare SRH between different countries, however, the indicator is useful to compare trends within country (Idler and Benyamini 1997). Answer choices to the question “How do you rate your health status in general?” were dichotomized to contrast good or sufficient (“very good”, “good”, “sufficient”) and poor (“poor” or “bad”) health status based on international standards. The wording of the question and the answers was consistent in all studies.

The main variable of interest among study participants was employment status. This information was obtained through self-reported answers of two survey questions: “Have you been engaged in paid work during the last 7 days, even if this work was only for an hour or just a few hours?” [YES/NO] and “Are you currently engaged in paid employment? Which of the following applies best to your status?” [Among others: ‘Full-Time employed’; ‘Part-Time Employed’]. The answers were sorted into to the categories of “Full-time employed”, “Part-time employed” and “Unemployed”. During the observational period 9.5% of the sample members were unemployed, 21.2% were part-time employed and 69.3% were full-time employed (cf. Table 1).

We controlled the estimates for differences regarding the covariates marital status and educational attainment. Married status was defined as answering “yes” to the question “Do you live together with a regular partner?” disregarding the legal status of the relationship (84.8% of the sample). Educational attainment was measured using the internationally comparable CASMIN scale (Brauns et al. 2003), in which we differentiated groups with primary, secondary and tertiary educational attainment (38.2, 38.4 and 23.3% of the study sample, respectively).

Four indicators were used to assess manifest (household income, at risk of poverty rate) and latent (life satisfaction, economic sorrows) consequences of unemployment which were regarded as potential mediators in the analyses. Household income was measured in Euros after state-wide redistribution and social security benefits (standardized for consumer prices in Germany in 2000) and was annually adjusted for household size by the new OECD equivalence scale (Förster and Pearson 2003; OECD 2008b). According to EU standards, the ‘at risk of poverty rate’ is defined as the share of persons with a household income below 60% of the population median of a corresponding year (Eurostat 2008). In the dataset, we computed an indicator variable for being below this threshold. Life satisfaction was measured through the question “Generally speaking, how satisfied are you with your life?” with answers on a Likert-type scale ranging from “0” to “10”. Economic sorrows were assessed using the question “Are you worried concerning your economic situation?” with the options “Yes, strongly”, “Yes, partly” and “No, not at all.” The answers were dichotomized to contrast strong (“Yes, strongly”) and minor sorrows (“Yes, partly”, “No, not at all”).

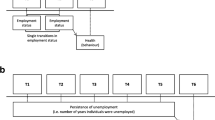

All statistical analyses were based on a pooled dataset including all panel waves from 1994 to 2008, allowing for trend analysis on the individual and population level. Analyses were performed using STATA 10.1 (StataCorp 2007). The study period was first split into four consecutive periods (1994–1998, 1999–2002, 2003–2005, 2006–2008), in which the prevalence of SRH was estimated separately for each period by employment status and gender. Age-adjusted odds ratios estimated through binary regression were then used to compare the risk of poor SRH between unemployed/part-time and full-time employed men and women. Subsequently, trends on the outcome in each employment group were estimated using multivariate logistic models that tested the main effects and interactions of dummy variables for employment status and a continuous time trend variable based on calendar year (0 = 1994, 0.07 = 1995,…,1.0 = 2008). We included stepwise control variables (age and education) and mediators into the models. Confidence intervals were estimated based on robust Huber-White estimates to control for the panel structure of the data (Huber 1967; White 1982). Finally, we estimated fixed effects logistic models (also known as conditional logistic regression models) with the same specifications. This modelling method has been used previously to assess the causal effect of income on health satisfaction (Frijters et al. 2005). In contrast to common logistic regression models that are fitting population-averaged effects for panel data, fixed effects models estimate average effects on the individual level while controlling for unobserved variable-bias between the respondents (Chamberlain 1980; Hosmer and Lemeshow 2000; Wooldridge 2010). Individuals who exhibited no changes in the included variables were considered non-informative and therefore excluded. Educational attainment of was not included in the fixed effects models, because it is constant over time on the individual level for our adult sample. Additionally, for multiple observations of a single respondent, calendar year (and the derived variable ‘trend’) and age are perfectly collinear. To resolve this collinearity, we had to exclude the main effect of ‘trend’ in the fixed effects models. The loss of information due to these exclusions is negligible for our research question. The fixed effects models are controlling for different baseline risks on the individual level (represented by ‘education’ as a covariate) and they are estimated to assess the changing effect of employment status on health over time and not the changing baseline risk over time (represented by the main effect of ‘trend’).

Results

Figure 1 shows the changes in prevalence of poor SRH from 1994 to 2008 by employment status and gender along with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. In the first period (1994–1998), the raw prevalence rates were 10.9 and 14.6% among full-time employed men and women and 23.6 and 24.7% among unemployed men and women. Until the 2006–2008 time period, the rates remained rather stable among the full-time employed men (11.0%) and declined slightly for full-time employed women (13.4%), while rates increased sharply among unemployed men (34.9%) and slightly among unemployed women (25.4%). The corresponding rates for the part-time employed were 19.2 and 13.7% in 1994–1998 and 20.3 and 12.9% in 2006–2008 for men and women, respectively.

The negative trend among unemployed men persisted after controlling for differences in the age structure of labour market groups. Figure 2 displays the linear changes of the prevalence of poor SRH between 1994 and 2008 by employment status and gender controlled for age. The linear change of the prevalence was insignificant among part-time and full-time employed men, while it increased significantly by 15.8% points among unemployed men. Among women, no group on the labour market experienced similar increases. The rates were stable among part-time and unemployed females while they increased slightly, but by a statistically significant amount of 2.9% points among full-time employed females.

Table 2 shows the gender-specific results of the binary logistic regression model on the risk of ‘bad’ or ‘poor’ SRH with standard errors that are controlled for clustering on the respondent level. The models were estimated stepwise and included multiple observations per respondent. The results of Model 1 show that, over the whole observational period, the odds ratio for a poor SRH among unemployed in comparison to full-time employed increased significantly from 1.99 in 1994 to 3.42 in 2008 for men [Table 2, Model 1; 1994: OR(unemployed), 2008: OR(unemployed) × OR(trend × unemployed)] and slightly from 1.78 to 2.04 for women (Table 2, Model 1) after controlling for differences regarding age, marital status or educational attainment. Meanwhile, the risk of poor SRH decreased somewhat among full-time employed men by 8% and considerably among full-time employed women by 26% (Table 2, Model 1, OR(trend): percent notation). Among the unemployed, the risk increased 58% for men and 14% for women [Table 2, Model 1, OR(trend) × OR(trend × unemployment): percent notation]. The trends observed among part-time employed men and women were roughly in line with their full-time employed counterparts.

In Models 3 and 4, we attributed the differences found in Model 2 successively to material and psychosocial consequences of unemployment (Table 2; under “Mediators”). Earning incomes below the poverty level and having economic sorrows were the strongest determinants of poor SRH for men and women. The introduction of the four pathway variables representing manifest and latent consequences of unemployment lead to a complete elimination of differences between unemployed and full-time employed men in 1994. These variables mediated the increasing differences between both groups only partially, which is represented by the interaction of the variables trend and unemployment. For women, the differences in trends regarding the risk of poor SRH between the unemployed and employed diminished after we controlled for the four variables. For men, the trends still remained notable.

The results of a fixed effects binary logistic regression model for panel data on the risk of ‘bad’ or ‘poor’ SRH are shown in Table 3. In contrast to the population average model in Table 2, this model fits the average effects of explanatory variables on the individual level and thus, uses the panel structure of the dataset more thoroughly. The model describes how changes in the explanatory variables over time affect the change in the outcome over the observational period (Wooldridge 2002). Overall, the results of the panel model roughly follow the results of the cross-sectional models (Table 2). For men, becoming unemployed increased the risk if ‘poor’ or ‘bad’ SRH by only 17% (OR = 1.17) in 1994, but in 2008, this risk increased severely by 148% (OR = 1.17 × 2.12 = 2.48). For women, the effect of becoming employed did not significantly change SRH (OR = 1.53). Additionally, OR (trend × unemployment) remained stable between Model 1 and Model 3 for men. Therefore, the possible consequences of unemployment did not mediate the increase of the effect of unemployment over time, while they had significant effects on the outcome (except poverty). For both sexes, lower income, lower life satisfaction and strong economic sorrows were correlated to increased risk for poor SRH. In addition, the effect of unemployment was partly mediated the four manifest and latent variables. Comparing Model 1 and 3 for men, the OR of unemployment in 2008 was reduced from 2.48 to 1.79; for women the corresponding values were 1.22 (Model 1) and 1.08 (Model 3).

Discussion

Using longitudinal data from a representative household survey, we analyzed the changing self-rated health status of the labour force in Germany. Overall, the results presented in this study showed that health inequalities between the three labour market groups widened for men and women between 1994 and 2008 in Germany. Adjusted for age, marital status and educational attainment, the disparities in risk of a poor SRH between the unemployed and full-time employed increased considerably by 76% for men and to a much lesser extent of 16% for women in the observational period.

In analyzing the changing association of unemployment and health within the labour force, it is unclear whether changes result from a causal effect of unemployment on health or as result of an increased health-related selection on the labour market (Korpi 2001; Schuring et al. 2007). We used the panel structure of the dataset to address this question in our analyses. We found that the widening health gap between the unemployed and full-time employed cannot be a result of selection because it largely persisted in the fixed effects panel models, during which we controlled for unobserved heterogeneity of the respondents and reported on an individual basis in contrast to averaged population effects. We also tested whether the increasing health inequalities between the employed and unemployed were a result of the increasing manifest and latent consequences of becoming unemployed in Germany. Our results indicate that the increasing inequalities were only partly attributable to common consequences of unemployment, such as income loss and economic sorrows.

Several studies have previously investigated changes in health inequalities in Germany (Nolte and McKee 2004; Kunst et al. 2005; Kroll and Lampert 2010). Using cross-sectional data of representative health surveys and comparing 1984–1986 and 1990, Kunst et al. 2005 also found increasing inequalities in SRH with respect to income among men and women in Western Germany. Nolte and McKee (2004) also found increased OR’s for income position in comparing data from 1992 and 1997 for West Germany, while finding reduced differences for East Germany using data from the GSOEP. However, these results are not fully comparable as the authors did not analyse gender-specific effects in their models and were primarily focused on the differences between East and West Germany. Additionally, in contrast to the aforementioned study, we excluded the panel wave of the year 1992 from our analysis because this was the first year East Germans (former residents of the GDR) were part of a regular panel wave and the SRH indicator was not included in the questionnaire in the following year (1993). Kroll and Lampert (2010) analyzed data from the GSOEP to examine increasing inequalities in SRH with respect to income. This study also found increasing differences by household income (after taxes and social benefits) for men and less severe differences for women. Overall, our results are in accordance with the results already published on general trends in health inequalities in Germany.

Remarkably, inequalities in SRH between unemployed and employed women did not increase significantly during the study period. Available evidence suggests that the consequences of unemployment are similar for men and women, but their coping strategies are different (Leeflang et al. 1992). Men seem to prefer problem-focussed coping strategies, while women tend to employ symptom-based strategies utilizing their social networks. Consequently, there are several possible explanations for our study results following these gendered differences. The coping mechanisms employed by women are perhaps more effective than that of men, particularly when faced with increased strains due to unemployment. Another possible explanation is that the women, who suffered the worst economic difficulties, left the labour force, which is a very undesirable or unfeasible option for men, especially following a male breadwinner model. On the other hand, the labour force participation rates of women rose steadily over the observational period (from 66 to 71% in the sample) and the poverty rates of women out of employment decreased from 16 to 11%, so the latter explanation is somewhat unlikely. Thus, the causes behind the observed gender-specific trends remain unclear and should be investigated further.

There are several limitations to our study. We used self-rated health as a proxy measure for the health status of the respondents. While using a less subjective measure based on medical records of the respondents or biomarkers would have been more accurate, this was not possible while using the GSOEP, which is an economic panel study by design. We also did not include more direct measures of the latent consequences of unemployment (e.g. feelings of status deprivation or loss of meaningful time structure). Unfortunately, adequate measures were not available in the GSOEP study, therefore we had to use life satisfaction and economic sorrows as proxy measures. A third limitation is the relatively large gap between the panel waves, which was about a year between the observations. While GSOEP includes monthly spell data for employment status, it does not include similar spells for the other variables used. Therefore, to maintain consistent levels of information between all variables, we excluded spell data for employment status. It would thus be meaningful to replicate our findings with a different panel dataset that includes more relevant pathway variables instead of just broad life satisfaction.

The results of this study, showing increased health inequalities with respect to employment status in Germany, are in line with recent changes in German labour market policy. During the 1990s, benefits for long and short-term unemployment were reduced several times and in the early 2000s, stricter rules and fines for the rejection of job offers were imposed and lesser opportunities for early retirement were available (Fleckenstein 2008; Zimmermann 2005). As a result, loosing one’s job became increasingly stressful for Germans and income inequality, as well as poverty rates, increased from the late 1990 s onward (Giesecke and Groß 2005; OECD 2008a; Frick and Grabka 2008; Kroll 2010). The results of the population average model as well as of the panel regression model indicated that the observed trends for men were partly mediated by the income and poverty risk of the respondents, which were previously shown to be negatively effected by the recent reforms (Goebel and Richter 2007). In addition, increased uncertainty, which also mediated the effects, has also been discussed as an important outcome of social change in Germany (Blossfeld et al. 2008). Therefore, it is likely that the increases in health inequalities by employment status in Germany observed in this study are, to some extent connected to the changes of the German ‘Sozialstaat’ in the last two decades.

References

Ahs A, Westerling R (2006) Self-rated health in relation to employment status during periods of high and of low levels of unemployment. Eur J Public Health 16(3):294–304

Alber J (2003) Recent developments in the German welfare state: basic continuity or a paradigm shift? In: Gilbert N, Van Voorhis RA (eds) Changing patterns of social protection. Transaction, London, pp 9–73

Arber S, Lahelma E (1993) Inequalities in women’s and men’s ill-health: Britain and Finland compared. Soc Sci Med 37(8):1055–1068

Avendano M, Kunst AE, van Lenthe F, Bos V, Costa G, Valkonen T, Cardano M, Harding S, Borgan JK, Glickman M, Reid A, Mackenbach JP (2005) Trends in socioeconomic disparities in stroke mortality in six European countries between 1981–1985 and 1991–1995. Am J Epidemiol 161(1):52–61. doi:10.1093/aje/kwi011

Bambra C, Eikemo TA (2009) Welfare state regimes, unemployment and health: a comparative study of the relationship between unemployment and self-reported health in 23 European countries. J Epidemiol Community Health 63(2):92–98

Bartley M (1994) Unemployment and ill health: understanding the relationship. J Epidemiol Community Health 48(4):333–337

Bartley M, Blane D, Davey Smith G (eds) (1998) The sociology of health inequalities. Blackwell, Oxford

Béland F, Birch S, Stoddart G (2002) Unemployment and health: contextual-level influences on the production of health in populations. Soc Sci Med 55(11):2033–2052

Blossfeld HP, Buchholz S, Hofäcker D, Hofmeister H, Kurz K, Mills M (2008) Globalisierung und die Veränderung sozialer Ungleichheiten in modernen Gesellschaften. Eine Zusammenfassung der Ergebnisse des GLOBALIFE-Projektes. Kölner Zeitschrift f Soziologie 59 (4):667–691

Brauns H, Scherer S, Steinmann S (2003) The CASMIN educational classification in international comparative research. In: Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik JHP, Wolf C (eds) Advances in cross-national comparison. Kluwer, New York, pp 221–244

Chamberlain G (1980) Analysis of covariance with qualitative data. Rev Econ Stud 47(1):225–238

Creed PA, Macintyre SR (2001) The relative effects of deprivation of the latent and manifest benefits of employment on the well-being of unemployed people. J Occup Health Psychol 6(4):324–331

Dalstra JAA, Kunst AE, Geurts JJM, Frenken FJM, Mackenbach JP (2002) Trends in socioeconomic health inequalities in the Netherlands, 1981–1999. J Epidemiol Community Health 56(12):927

Eikemo TA, Bambra C, Joyce K, Dahl E (2008a) Welfare state regimes and income-related health inequalities: a comparison of 23 European countries. Eur J Public Health 18(6):593–599

Eikemo TA, Huisman M, Bambra C, Kunst AE (2008b) Health inequalities according to educational level in different welfare regimes: a comparison of 23 European countries. Sociol Health Illn 30(4):565–582

Eurostat (2008) Measuring progress towards a more sustainable Europe—2007 monitoring report of the EU sustainable development strategy. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg

Fleckenstein T (2008) Restructuring welfare for the unemployed: the Hartz legislation in Germany. J Eur Soc Policy 18(2):177–188

Förster M, Pearson M (2003) Income distribution and poverty in the OECD area: trends and driving forces. OECD Econ Stud 2002:8

Frick JR, Grabka M (2008) Niedrigere Arbeitslosigkeit sorgt für weniger Armutsrisiko und Ungleichheit. DIW Wochenbericht 75(38):556–566

Frijters P, Haisken-DeNew JP, Shields MA (2005) The causal effect of income on health: Evidence from German reunification. J Health Econ 24(5):997–1017

Giesecke J, Groß M (2005) Arbeitsmarktreformen und Ungleichheit. APuZ 16:25–31

Goebel J, Richter M (2007) Nach der Einführung von Arbeitslosengeld II: Deutlich mehr Verlierer als Gewinner unter den Hilfeempfängern. DIW Wochenbericht 2007(50):753–761

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S (2000) Applied logistic regression. Wiley series in probability and statistics. Texts and references section, 2nd edn. Wiley, New York

Huber PJ (1967) The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under non-standard conditions. In: Neyman J (ed) Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability. University of California Press, Berkeley, pp 221–233

Idler EL, Benyamini Y (1997) Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav 38(1):21–37

TNS Infratest, SOEP-Group (2006) SOEP 2006 Method Report. TNS Infratest Sozilforschung. http://www.diw-berlin.de/documents/dokumentenarchiv/17/diw_01.c.83168.de/meth_2006.pdf. Accessed 1 Dec 2009

Korpi T (2001) Accumulating disadvantage. Longitudinal analyses of unemployment and physical health in representative samples of the Swedish population. Eur Sociol Rev 17(3):255–273

Kroll LE (2010) Sozialer Wandel, soziale Ungleichheit und Gesundheit. Die Entwicklung sozialer und gesundheitlicher Ungleichheiten in Deutschland zwischen 1984 und 2006. VS Verlag, Wiesbaden

Kroll LE, Lampert T (2010) Zunehmende Unterschiede im subjektiven Gesundheitszustand zwischen den Einkommensgruppen. Informationsdienst Soziale Indikatoren 43(January 2010):5–8

Kunst AE, Bos V, Lahelma E, Bartley M, Lissau I, Regidor E, Mielck A, Cardano M, Dalstra JAA, Geurts JJM, Helmert U, Lennartsson C, Ramm J, Spadea T, Stronegger WJ, Mackenbach JP (2005) Trends in socioeconomic inequalities in self-assessed health in 10 European countries. Int J Epidemiol 34(2):295–305

Lahelma E, Kivela K, Roos E, Tuominen T, Dahl E, Diderichsen F, Elstad JI, Lissau I, Lundberg O, Rahkonen O (2002) Analysing changes of health inequalities in the Nordic welfare states. Soc Sci Med 55(4):609–625

Leeflang RL, Klein-Hesselink DJ, Spruit IP (1992) Health effects of unemployment–II. Men and women. Soc Sci Med 34(4):351–363

Mackenbach JP (2006) Health inequalities: Europe in profile. UK Presidency of the EU, Rotterdam

Mackenbach JP, Bos V, Andersen O, Cardano M, Costa G, Harding S, Reid A, Hemstrom O, Valkonen T, Kunst AE (2003) Widening socioeconomic inequalities in mortality in six Western European countries. Int J Epidemiol 32(5):830–837. doi:10.1093/ije/dyg209

Mackenbach JP, Stirbu I, Roskam A-JR, Schaap MM, Menvielle G, Leinsalu M, Kunst AE, the European Union Working Group on Socioeconomic Inequalities in H (2008) Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. N Engl J Med 358(23):2468–2481

Mathers CD, Schofield DJ (1998) The health consequences of unemployment: the evidence. Med J Aust 168(4):178–182

Mazzuco S, Suhrcke M (2010) Health inequalities in Europe: new insights from European labour force surveys. J Epidemiol Community Health (online first)

Nolte E, McKee M (2004) Changing health inequalities in east and west Germany since unification. Soc Sci Med 58(1):119

OECD (2008a) Growing unequal? Income distribution and poverty in OECD countries. Country note: GERMANY

OECD (2008b) Income distribution—inequality. OECD.StatExtracts, Paris

Rodriguez E (2002) Marginal employment and health in Britain and Germany: does unstable employment predict health? Soc Sci Med 55(6):963–979

Schuring M, Burdorf L, Kunst A, Mackenbach J (2007) The effects of ill health on entering and maintaining paid employment: evidence in European countries. J Epidemiol Community Health 61(7):597–604

StataCorp (2007) Stata Statistical Software: release 10.0. Stata Corporation, College Station, TX

Wagner GG, Frick JR, Schupp J (2007) The German socio-economic panel study (SOEP)—scope, evolution and enhancements. Schmollers Jahrbuch 127(1):139–169

White H (1982) Maximum likelihood estimation of misspecified models. Econometrica 50:1–25

Wooldridge JM (2002) Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT Press, Cambridge

Wooldridge JM (2010) Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data, 2nd edn. MIT Press, Cambridge

Zimmermann K (2005) Eine Zeitenwende am Arbeitsmarkt. APuZ 16:3–5

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editors, an anonymous reviewer and Kim Truong for commenting on earlier drafts of this paper.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kroll, L.E., Lampert, T. Changing health inequalities in Germany from 1994 to 2008 between employed and unemployed adults. Int J Public Health 56, 329–339 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-011-0233-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-011-0233-0