Abstract

Background

Perioperative allogeneic blood transfusion is associated with poor oncologic outcomes in multiple malignancies. The effect of blood transfusion on recurrence and survival in distal cholangiocarcinoma (DCC) is not known.

Methods

All patients with DCC who underwent curative-intent pancreaticoduodenectomy at 10 institutions from 2000 to 2015 were included. Primary outcomes were recurrence-free (RFS) and overall survival (OS).

Results

Among 314 patients with DCC, 191 (61%) underwent curative-intent pancreaticoduodenectomy. Fifty-three patients (28%) received perioperative blood transfusions, with a median of 2 units. There were no differences in baseline demographics or operative data between transfusion and no-transfusion groups. Compared with no-transfusion, patients who received a transfusion were more likely to have (+) margins (28 vs 14%; p = 0.034) and major complications (46 vs 16%; p < 0.001). Transfusion was associated with worse median RFS (19 vs 32 months; p = 0.006) and OS (15 vs 29 months; p = 0.003), which persisted on multivariable (MV) analysis for both RFS [hazard ratio (HR) 1.8; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.1–3.0; p = 0.031] and OS (HR 1.9; 95% CI 1.1–3.3; p = 0.018), after controlling for portal vein resection, estimated blood loss (EBL), grade, lymphovascular invasion (LVI), and major complications. Similarly, transfusion of ≥ 2 pRBCs was associated with lower RFS (17 vs 32 months; p < 0.001) and OS (14 vs 29 months; p < 0.001), which again persisted on MV analysis for both RFS (HR 2.6; 95% CI 1.4–4.5; p = 0.001) and OS (HR 4.0; 95% CI 2.2–7.5; p < 0.001). The RFS and OS of patients transfused 1 unit was comparable to patients who were not transfused.

Conclusion

Perioperative blood transfusion is associated with decreased RFS and OS after resection for distal cholangiocarcinoma, after accounting for known adverse pathologic factors. Volume of transfusion seems to exert an independent effect, as 1 unit was not associated with the same adverse effects as ≥ 2 units.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Distal cholangiocarcinoma (DCC) is a rare and lethal periampullary cancer that arises from the epithelium of the distal third of the common bile duct.1,2 DCC represents nearly 40% of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas and about 14% of all periampullary tumors.3,4,5,6 Although the pathophysiology of DCC is distinct, it is often treated similarly to other biliary tract malignancies.1 As such, its incidence is difficult to quantify, as epidemiologic studies frequently combine cases of intrahepatic, hilar, and distal cholangiocarcinoma, in addition to gallbladder cancer.1 Surgical resection is the primary management strategy for DCC, and as with other periampullary tumors, achievement of an R0 resection is of critical importance to improve survival.7 Nonetheless, prognosis remains poor, with approximately 20–40% overall survival (OS) at 5 years and median survival of 3.5 years.3,8

There are a number of prognostic factors that impact survival in patients with DCC. These factors include R1/R2 surgical margin status, tumor size > 2 cm, poor tumor differentiation, positive lymph nodes, lymphovascular invasion, and perineural invasion.1,3,8,9 Presence of such negative prognostic factors may reduce patient overall survival up to sixfold.9 However, given that these factors are primarily a manifestation of tumor biology and only discovered at or after surgical resection, oncology care teams are limited in their ability to proactively intervene to improve patient survival.

One prognostic factor that the surgical oncologist can control, and which has been shown to negatively impact survival in several malignancies, is the use of perioperative allogeneic packed red blood cell (pRBC) transfusion. Although evidence has been conflicting with regard to the number of units transfused and the timing of transfusion,10,11,12,13 multiple studies have reported an independent association between perioperative blood transfusion and poor prognosis, as well as postoperative morbidity in cancer patients.10,14,15,16 While worse outcomes have been noted among transfused patients with lung, pancreatic, gastric, bladder, adrenal, renal, and colorectal cancer, no studies to date have specifically assessed for a negative prognostic association in DCC.10,11,13,14,15,17,18,19 Given the increasing evidence that DCC is a distinct histopathologic disease, understanding the role that allogeneic blood transfusion may play in exacerbating poor outcomes is essential to optimizing the management of patients with this disease.2 The aim of this study is to evaluate the association of pRBC transfusion with both disease recurrence and overall survival among patients with DCC using a multiinstitutional patient cohort from various academic institutions across the USA.

Methods

Study Population

The US Extrahepatic Biliary Malignancy Consortium (USEBMC) is a collaboration of 10 high-volume academic institutions from across the USA, including Emory University, Johns Hopkins University, New York University, The Ohio State University, Stanford University, University of Louisville, University of Wisconsin, Vanderbilt University, Wake Forest University, and Washington University in St. Louis. This database encompasses all patients from these institutions with extrahepatic biliary malignancies, specifically gallbladder cancer, hilar cholangiocarcinoma, and distal cholangiocarcinoma (DCC), who underwent surgical resection from January 1, 2000 to December 31, 2015. For the purpose of this study, all patients who underwent curative-intent pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) for primary DCC with preoperative and postoperative pRBC transfusion data available were included in analysis. Patients who died within 30 days as well as patients who underwent an R2 resection were excluded. The primary end-point was recurrence-free survival (RFS), and the secondary end-point was overall survival (OS).

Institutional review board approval was obtained at each institution prior to data retrieval. Retrospective chart review was used to collect pertinent baseline demographic, preoperative, operative, pathologic, and postoperative data. Pathologic staging was determined according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 7th edition staging system.20 The Charlson Comorbidity Scoring System was used to define preoperative comorbidities, and the severity of postoperative complications was classified according to the Clavien–Dindo grading system.21 Survival data were also collected and corroborated with the Social Security Death Index, when necessary. Disease recurrence was defined as the return of disease at any site, as obtained by patient medical records, imaging reports, and/or biopsy results. The threshold for transfusion was at the discretion of the treating surgeon, anesthesiologist, and postoperative care team.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive and comparative statistical analyses were performed for the entire cohort using SPSS version 23.0 (Armonk New York Software, IBM Inc.). RFS was calculated from the date of operation to the date of recurrence of disease, while OS was calculated from the date of operation to the date of death. Chi squared analyses and Student’s t test were used to compare categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Kaplan–Meier log-rank plots were calculated for both RFS and OS; univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses were similarly used to assess the prognostic value of clinicopathologic factors for RFS and OS. Statistical significance was predefined as a value of p < 0.05.

Results

Study Population

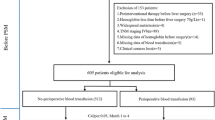

Among 314 patients with DCC, 212 (68%) underwent a curative-intent pancreatoduodenectomy. Twenty-one patients were missing preoperative or postoperative pRBC transfusion data and were excluded. As such, the final analytic cohort consisted of 191 patients. Baseline demographics and clinicopathologic factors for the study cohort are summarized in Table 1. Median age was 67 years, and 61% (n = 117) were male. A nearly equal number of patients underwent pylorus-preserving PD (n = 94; 49%) versus classic PD (n = 97; 51%); the overwhelming majority had an open procedure (n = 188; 99%). Mean estimated blood loss (EBL) was 618 mL. Most patients had advanced T-stage (T3/T4: n = 141; 76.6%), and over half (53%; n = 100) had lymph node metastasis and other adverse disease markers such as lymphovascular invasion (LVI) (51%; n = 87) and perineural invasion (PNI) (82%; n = 145). At the time of last follow-up, 78 patients (45%) had disease recurrence and 119 patients (62%) had died. Median follow-up for survivors was 18 months.

Fifty-three (28%) patients received a perioperative pRBC transfusion. Of these, 17 patients received only an intraoperative transfusion while 19 patients received only postoperative transfusion. The median number of pRBC units transfused was 2 (interquartile range 2.75 units). There was no difference in baseline demographics between patients who were transfused and those who were not transfused (Table 1). Perioperative pRBC transfusion was associated with increased EBL (1056 vs 413 mL; p = 0.006), positive resection margins (28 vs 14%; p = 0.034), and increased tumor size (25 vs 21 mm; p = 0.017). Transfusion was also correlated with increased major postoperative complications (46 vs 16%; p < 0.001) and longer length of hospital stay (19 vs 11 days; p = 0.001). There was no difference in receipt of neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy between groups.

Transfusion and Predictors of Recurrence-Free Survival

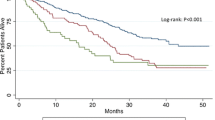

Among the 191 patients with perioperative pRBC transfusion data who underwent survival analysis, median follow-up was 18 months (range 0.6–137.2 months). On univariable Cox regression, perioperative blood transfusion (HR 1.95; 95% CI 1.2–3.2; p = 0.007), portal vein resection (HR 3.53; 95% CI 1.3–9.7; p = 0.015), and major postoperative complications (HR 2.0; 95% CI 1.2–3.3; p = 0.007) were each associated with decreased RFS (Table 2). Other factors such as tumor size, margin status, T-stage, or lymph node metastasis were not associated with RFS. On Kaplan–Meier analysis, patients who were transfused had a median RFS of 19 months versus 32 months for patients who were not transfused (p = 0.006) (Fig. 1a). Even after accounting for portal vein resection and major postoperative complications, perioperative blood transfusion remained independently significant on multivariable analysis, conferring a nearly twofold increase in risk of disease recurrence compared with no transfusion (Table 2).

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for recurrence-free survival among transfusion versus no-transfusion groups: a There is a statistically significant difference in recurrence-free survival (RFS) between patients who were transfused (n = 42) and patients who were not transfused (n = 127), where those who were transfused had a median survival of 19 months compared with 32 months for those were not transfused (p = 0.006); b When considering the amount of pRBCs transfused, patients who received at least 2 units of pRBCs perioperatively (n = 29) had a median RFS of 17 months versus 32 months for those transfused with 1 unit of pRBCs or less (n = 132) (p < 0.001)

When examining the effect of volume of transfusion, a worse RFS was observed among patients transfused with 2 or more units of pRBCs (HR 2.74; 95% CI 1.6–4.8; p < 0.001) versus patients transfused 1 unit or less. Patients who were transfused with ≥ 2 units of pRBCs had a median RFS of 17 months versus 32 months for those transfused with 0–1 units of pRBCs (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1b). This finding persisted on multivariable analysis, after accounting for portal vein resection and major postoperative complications (HR 2.6; 95% CI 1.4–4.5; p = 0.001). There was no difference in RFS for patients transfused with 1 unit of pRBCs compared with those who were not transfused (HR 0.87; 95% CI 0.3–2.8; p = 0.810). Postoperative versus intraoperative timing of transfusion was not found to be associated with recurrence (p = 0.211).

Transfusion and Predictors of Overall Survival

On analysis of OS, several perioperative and clinicopathologic factors were associated with increased risk of death on univariable Cox regression, including portal vein resection (HR 3.57; 95% CI 1.6–8.2; p = 0.003), EBL (HR 1.0; 95% CI 1.0–1.0; p = 0.012), poor grade (HR 4.5; 95% CI 1.6–12.6; p = 0.004), LVI (HR 1.5; 95% CI 1.0–2.2; p = 0.038), and major postoperative complications (HR 1.9; 95% CI 1.3–2.7; p = 0.002) (Table 3). In addition, perioperative blood transfusion was associated with a 1.76 times increase in risk of mortality (p = 0.003). Specifically, patients who received a transfusion had a lower median OS compared with those who were not transfused (15 vs 29 months; p = 0.003) (Fig. 2a). Even in a multivariable model, after accounting for other adverse clinicopathologic factors, perioperative pRBC transfusion remained independently associated with worse survival (HR 1.9; 95% CI 1.1–3.3; p = 0.018).

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for overall survival among transfusion versus no-transfusion groups: a There is a statistically significant difference in overall survival (OS) between patients who were transfused (n = 53) and patients who were not transfused (n = 138), where those who were transfused had a median survival of 15 months compared with 29 months for those were not transfused (p = 0.003); b When considering the amount of pRBCs transfused, patients who received at least 2 units of pRBCs perioperatively (n = 37) had a median OS of 14 months versus 29 months for those transfused with 1 unit of pRBCs or less (n = 145) (p < 0.001)

A dose-dependent association between number of pRBC units transfused and OS was noted on both Cox regression and Kaplan–Meier analysis. Patients transfused with 2 or more units of pRBCs had an over twofold risk of mortality (HR 2.5; 95% CI 1.6–3.7; p < 0.001), as well as a decreased median OS (14 vs 29 months; p < 0.001) compared with patients transfused with 1 or 0 units (Fig. 2b). The adverse impact of multiple unit transfusion on survival persisted on multivariable analysis, after accounting for portal vein resection, EBL, grade, LVI, and major postoperative complications (HR 4.0; 95% CI 2.2–7.5; p < 0.001). As with RFS, transfusion with 1 unit versus 0 units of pRBCs was not associated with worse OS (p = 0.621). Likewise, no difference in survival was observed relative to intraoperative versus postoperative timing of transfusion (0.247).

Discussion

This study is the first to the authors’ knowledge to assess the relationship of perioperative allogeneic pRBC transfusion with recurrence and survival outcomes among patients undergoing curative-intent resection of distal cholangiocarcinoma. In this study cohort, pRBC transfusion was associated with decreased RFS and OS after resection for DCC, even after accounting for other known adverse clinicopathologic factors on multivariable analysis. Moreover, volume of transfusion also seemed to exert an independent association on survival analysis, as transfusion with 2 or more units was correlated with worse RFS and OS compared with transfusion of 0 or 1 unit. Together, these findings support prior studies, which had reported a deleterious association between pRBC transfusion and oncologic outcomes.10,11,12,13,14,22,23

Although perioperative pRBC transfusion has been associated with worse survival in multiple solid organ malignancies, the mechanism through which transfusion exerts its injurious effects remains unclear. The major concern stems from the theory that allogeneic blood transfusion acts as an immunosuppresor by causing a systemic inflammatory response through the release of cytokines and by directly changing plasma concentrations of inflammatory mediators.24 Such cytokines and inflammatory mediators have been shown to influence tumor recurrence in vivo and are released ubiquitously with the stress of surgery.25,26 Blood transfusion may thus act synergistically to exaggerate the surgery-induced cytokine response, worsening prognosis and promoting tumor recurrence.24,27,28 Indeed, the current study demonstrated that patients with DCC who had a perioperative blood transfusion were nearly twice as likely to recur, even after controlling for markers of worse tumor biology (such as the need for portal vein resection) and major postoperative complications, another possible source of cytokine release. Regardless of the mechanism, these findings corroborate current data implicating allogeneic blood transfusion as a negative prognostic factor.

While the majority of studies to date support the association between transfusion and poor oncologic outcomes, investigations into whether volume of transfusion affects cancer recurrence and survival have been conflicting. Studies assessing transfusion by Squires et al. in gastric cancer and Poorman et al. in adrenocortical carcinoma reported no difference in RFS or OS based on the number of units transfused.10,13 However, in another study by Kneuertz and colleagues, transfusion of > 2 units of pRBCs was associated with both decreased RFS and OS among patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.12 Likewise, Postlewait et al. also reported a decreased disease-specific survival with receipt of ≥ 3 units of pRBCs when examining the role of transfusion in outcomes of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer.11 Similar to the studies by Kneuertz and Postlewait, the current study noted that transfusion with 2 or more units was associated with both a worse RFS (HR 2.6; p = 0.001) and OS (HR 4.0; p < 0.001), even when accounting for other poor prognostic variables. Of note, survival among patients who received only 1 unit was comparable to patients who had not received any transfusions. The timing of transfusion (intraoperative vs postoperative) was not found to influence outcomes.

Given the concern over the possible harmful consequences of allogeneic blood transfusion, various measures exist in the healthcare system to both control the circumstances under which transfusions are administered and proactively decrease their necessity in the perioperative period. Although there is no current standardized transfusion protocol that is universally applied, guidelines recommend a restrictive strategy of blood transfusion for hemoglobin < 7.0 g per deciliter as determined by the TRICC randomized, controlled clinical trial.29 Nevertheless, these guidelines were created for intensive care unit patients, not surgical patients, and are thus limited in their applicability to the unpredictable circumstances of the operating room. While measures are actively underway to standardize transfusion thresholds in surgical patients specifically, as evidenced by the Blood Management Program developed at Johns Hopkins Hospital, and by the Transfusion Requirements in Cardiac Surgery III (TRICS III) trial, these are still emerging.30,31 As such, other efforts to minimize the need for allogeneic transfusions have also been developed. Two such techniques include preoperative autologous blood donation, where patients donate their own blood in the weeks leading up to their procedure, and acute normovolemic hemodilution, where whole blood is removed immediately prior to the operation to a target of 8.0 g/dL, while maintaining euvolemia through replacement of half of the volume removed with 5% albumin and the other half with crystalloid.32 Preoperative iron supplementation is another promising strategy to decrease the need for transfusion.33 When successful, these interventions can mitigate the significant postoperative risks and worse oncologic outcomes associated with the administration of allogeneic blood products.

This study is limited by its retrospective design, which restricts the interpretation of results to defining associations rather than causality. Furthermore, although transfusion data were available for each patient, individual preoperative and intraoperative hemoglobin levels were not collected at the time of the multiinstitutional collaboration. Analyses were also limited by missing data and the current absence of a standardized transfusion protocol, leaving the final decision to transfuse to the surgeon and patient management team. Despite its limitations, this study is unique in its multiinstitutional design for the evaluation of such a rare disease, making it generalizable on a national scale..

In conclusion, allogeneic red blood cell transfusion is independently associated with decreased RFS and OS among patients who undergo curative-intent resection for distal cholangiocarcinoma. Volume of transfusion plays an independent role, with ≥ 2 units being associated with worse survival compared with transfusion with 1 unit or less. These findings support the judicious use of perioperative blood transfusions with the intent of ultimately optimizing oncologic outcomes.

References

Dickson PV, Behrman SW. Distal cholangiocarcinoma. Surg Clin North Am. 2014;94(2):325–42.

Ethun CG, Lopez-Aguiar AG, Pawlik TM, et al. Distal cholangiocarcinoma and pancreas adenocarcinoma: are they really the same disease? A 13-institution study from the US Extrahepatic Biliary Malignancy Consortium and the Central Pancreas Consortium. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;224(4):406–13.

DeOliveira ML, Cunningham SC, Cameron JL, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma: thirty-one-year experience with 564 patients at a single institution. Ann Surg. 2007;245(5):755–62.

Riall TS, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, et al. Resected periampullary adenocarcinoma: 5-year survivors and their 6- to 10-year follow-up. Surgery. 2006;140(5):764–72.

Hatzaras I, George N, Muscarella P, Melvin WS, Ellison EC, Bloomston M. Predictors of survival in periampullary cancers following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(4):991–97.

Cameron JL, He J. Two thousand consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220(4):530–36.

Konishi M, Iwasaki M, Ochiai A, Hasebe T, Ojima H, Yanagisawa A. Clinical impact of intraoperative histological examination of the ductal resection margin in extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2010;97(9):1363–8.

Kiriyama M, Ebata T, Aoba T, et al. Prognostic impact of lymph node metastasis in distal cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2015;102(4):399–406.

Murakami Y, Uemura K, Hayashidani Y, et al. Prognostic significance of lymph node metastasis and surgical margin status for distal cholangiocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95(3):207–12.

Squires MH, 3rd, Kooby DA, Poultsides GA, et al. Effect of perioperative transfusion on recurrence and survival after gastric cancer resection: a 7-institution analysis of 765 patients from the US Gastric Cancer Collaborative. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221(3):767–77.

Postlewait LM, Squires MH, Kooby DA,Weber SM, Scoggins CR, Cardona K, Cho CS, Martin RCG, Winslow ER, Maithel SK. The relationship of blood transfusion with peri-operative and long-term outcomes after major hepatectomy for metastatic colorectal cancer: a multi-institutional study of 456 patients. HPB. 2015;1–8.

Kneuertz PJ, Patel SH, Chu CK, et al. Effects of perioperative red blood cell transfusion on disease recurrence and survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(5):1327–34.

Poorman CE, Postlewait LM, Ethun CG, et al. Blood transfusion and survival for resected adrenocortical carcinoma: a study from the United States Adrenocortical Carcinoma Group. Am Surg. 2017;83(7):761–68.

Sutton JM, Kooby DA, Wilson GC, et al. Perioperative blood transfusion is associated with decreased survival in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a multi-institutional study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18(9):1575–87.

Gierth M, Aziz A, Fritsche HM, et al. The effect of intra- and postoperative allogenic blood transfusion on patients’ survival undergoing radical cystectomy for urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. World J Urol. 2014;32(6):1447–53.

Amato A, Pescatori M. Perioperative blood transfusions for the recurrence of colorectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD005033.

Keller SM, Groshen S, Kaiser LR. Blood transfusion and lung cancer recurrence. Ann Thorac Surg. 1989;48(5):746–47.

Manyonda IT, Shaw DE, Foulkes A, Osborn DE. Renal cell carcinoma: blood transfusion and survival. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293(6546):537–38.

Linder BJ, Thompson RH, Leibovich BC, et al. The impact of perioperative blood transfusion on survival after nephrectomy for non-metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC). BJU Int. 2014;114(3):368–74.

Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(6):1471–74.

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240(2):205–13.

Wang T, Luo L, Huang H, et al. Perioperative blood transfusion is associated with worse clinical outcomes in resected lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97(5):1827–37.

Perisanidis C, Dettke M, Papadogeorgakis N, et al. Transfusion of allogenic leukocyte-depleted packed red blood cells is associated with postoperative morbidity in patients undergoing oral and oropharyngeal cancer surgery. Oral Oncol. 2012;48(4):372–78.

Miki C, Hiro J, Ojima E, Inoue Y, Mohri Y, Kusunoki M. Perioperative allogeneic blood transfusion, the related cytokine response and long-term survival after potentially curative resection of colorectal cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2006;18(1):60–66.

Hofer SO, Shrayer D, Reichner JS, Hoekstra HJ, Wanebo HJ. Wound-induced tumor progression: a probable role in recurrence after tumor resection. Arch Surg. 1998;133(4):383–89.

Hofer SO, Molema G, Hermens RA, Wanebo HJ, Reichner JS, Hoekstra HJ. The effect of surgical wounding on tumour development. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1999;25(3):231–43.

Pandey P, Chaudhary R, Aggarwal A, Kumar R, Khetan D, Verma A. Transfusion-associated immunomodulation: Quantitative changes in cytokines as a measure of immune responsiveness after one time blood transfusion in neurosurgery patients. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2010;4(2):78–85.

Innerhofer P, Tilz G, Fuchs D, et al. Immunologic changes after transfusion of autologous or allogeneic buffy coat-poor versus WBC-reduced blood transfusions in patients undergoing arthroplasty. II. Activation of T cells, macrophages, and cell-mediated lympholysis. Transfusion. 2000;40(7):821–27.

Hebert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(6):409–17.

Gani F, Cerullo M, Ejaz A, et al. Implementation of a blood management program at a tertiary care hospital: effect on transfusion practices and clinical outcomes among patients undergoing surgery. Ann Surg. 2017.

Shehata N, Whitlock R, Fergusson DA, et al. Transfusion Requirements in Cardiac Surgery III (TRICS III): study design of a randomized controlled trial. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018;32(1):121–29.

Jarnagin WR, Gonen M, Maithel SK, et al. A prospective randomized trial of acute normovolemic hemodilution compared to standard intraoperative management in patients undergoing major hepatic resection. Ann Surg. 2008;248(3):360–69.

Hallet J, Hanif A, Callum J, et al. The impact of perioperative iron on the use of red blood cell transfusions in gastrointestinal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transfus Med Rev. 2014;28(4):205–11.

Acknowledgment

Funding provided in part by the Katz Foundation. Supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR000454 and TL1TR000456. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lopez-Aguiar, A.G., Ethun, C.G., Pawlik, T.M. et al. Association of Perioperative Transfusion with Recurrence and Survival After Resection of Distal Cholangiocarcinoma: A 10-Institution Study from the US Extrahepatic Biliary Malignancy Consortium. Ann Surg Oncol 26, 1814–1823 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-019-07306-x

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-019-07306-x