Abstract

Background

The efficacy of endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) for determining T category is variable for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). We aimed to assess the efficacy of EUS in accurately identifying T category for ESCC based on the 8th AJCC Cancer Staging Manual.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was conducted using a prospectively collected ESCC database from January 2003 to December 2015, in which all patients underwent EUS examination followed by esophagectomy. The efficacy of EUS was evaluated by sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy compared with pathological T category as gold standard. Overall survival of different EUS-T (uT) categories was assessed.

Results

In total, 1434 patients were included, of whom 58.2% were correctly classified by EUS, with 17.9% being overstaged and 23.9% being understaged. The sensitivity and accuracy of EUS for Tis, T1a, T1b, T2, T3, and T4a categories were 15.8 and 98.8%, 16.3 and 95.7%, 33.1 and 89.3%, 56.8 and 65.0%, 65.8 and 70.0%, and 27.3 and 97.5%, respectively. The survival difference between uT1a and uT1b was not statistically significant (p = 0.90), nor was that between uT4a and uT4b (p = 0.34). However, when uT category was integrated as uTis, uT1, uT2, uT3, and uT4, overall survival was clearly distinguished between the categories (p < 0.01).

Conclusions

EUS is in general feasible for classifying clinical T category for ESCC. However, EUS should be used with caution for discriminating between Tis, T1a, and T1b disease, as well as T4 disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Clinical T (cT) category, which is an important component of the clinical tumor, node, metastasis cancer staging system, is crucial for clinicians making initial therapeutic decisions for patients with esophageal cancer.1 Computed tomography is the most commonly used method to assess T category, but it can be inaccurate due to inability to differentiate the layers of the esophageal wall.2,3,4 Two metaanalyses have suggested that endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is a more accurate method for staging esophageal cancer, especially for determining T category.5,6 However, the efficacy of EUS for determining an individual patient’s T category is variable.7,8,9,10

Currently, only a few studies with small sample size have assessed patient survival based on different EUS-T (uT) staging categories, but none of them has focused on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC).8,11,12 More than half of all patients with esophageal cancer are Chinese,13 and the most common pathological type of esophageal cancer is squamous cell carcinoma in the East.14 Therefore, more data from China are required to evaluate the efficacy of EUS in classifying cT category for patients with ESCC.

We present herein data from 1434 surgical ESCC cases with the purpose of assessing the efficacy of EUS in classifying cT category and evaluating patient survival prognosis based on uT categories.

Patients and Methods

Patient Selection

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center. The study was conducted using data from an esophageal cancer database composed of 2274 consecutive cases of surgically treated ESCC performed at our center between January 2003 and December 2015. The data of the study are recorded at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center for future reference, with approval number RDDA2017000421. All patients included in this analysis met the following criteria: (1) their disease was histologically defined as ESCC, (2) they underwent R0 resection, and (3) they underwent pretreatment EUS.

The exclusion criteria were (1) surgery that was preceded by chemotherapy or radiotherapy (neoadjuvant therapy), (2) multiple primary esophageal tumors, (3) concurrent or previous other primary cancers, or (4) tumors with bulky obstruction that EUS failed to pass through.

The inclusion process used in this study is shown in Fig. S1 (online only). In this study, EUS was not performed in 363 patients, including the cases that EUS failed to pass through, and the cases that only underwent conventional esophageal endoscopy examination. In our center, many patients underwent endoscopic examination in outpatient clinic. Unfortunately, the cost in outpatient clinic cannot be covered by medical insurance in mainland China, which may hinder use of EUS in our center. For obstructing tumors, the status of tumor depth is hard to assess accurately by EUS. Therefore, doctors need to combine the results of computed tomography (CT) or positron emission tomography (PET)-CT and EUS to determine the staging for them.

Perioperative death was defined as death within 30 days of surgery or any time after surgery if the patient did not leave the hospital alive.

Endoscopic Ultrasonographic Staging

EUS was performed by six endoscopic experts (1353 cases) and six trainees (81 cases) under guidance from these experts. All experts have advanced training, and each of them performed EUS examination for about 250–300 cases per year. These six experts performed 369, 317, 268, 144, 141, and 114 cases of EUS respectively in this study. Trainees are required to have at least 200 cases of EUS under guidance from experts before being certified to perform EUS independently.

In general, EUS examination started from the stomach to evaluate for presence of lymph nodes around celiac axis, left gastric artery, lesser gastric curvature, and cardia. Then, EUS was slowly pulled back into the chest to measure the tumor, including maximal thickness and depth of infiltration. In addition, lymph nodes of paraesophagus, subcarinal region, and bilateral esophagobronchial groove were also evaluated. The images and interpretation of EUS examination were recorded in the EUS note; For example, visualization of the celiac axis was documented in 1088 cases in this study.

The EUS reports were carefully reviewed, and the uT category was restaged according to the following categories from the 8th American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual for the Esophagus and Esophagogastric Junction: uTis, noninvasive neoplastic epithelia; uT1a, tumor invading the lamina or muscularis mucosa; uT1b, invasion up to the submucosa; uT2, invasion into the muscularis propria; uT3, tumor invades the adventitia; uT4, tumor invades the adjacent structures (uT4a, structures may be resectable; uT4b, structures are usually unresectable).15

Patients were advised to receive both EUS and computed tomography (CT) for diagnosis and staging. Of the 1434 patients who underwent EUS, 1329 also underwent CT, and the others underwent combined positron emission tomography and CT (PET-CT). PET-CT was not performed routinely because it has not been covered by medical insurance in mainland China. If CT or PET-CT was performed prior to EUS, the EUS operators will be aware of the results of them.

Pathological Staging

Pathological T (pT) category was also restaged using the 8th AJCC Cancer Staging Manual for the Esophagus and Esophagogastric Junction.15

Follow-Up

In general, follow-up examination was recommended every 3 months for the first year, every 4 months for the second year, and twice a year thereafter. For patients receiving additional therapy and/or follow-up outside of our center, telephone follow-up was conducted once a year. In addition, to obtain more complete data, telephone follow-up was conducted for all the patients from September to November 2016. Data including disease status and survival were recorded in the database from information provided by subsequent surveillance and treatment visits at our center and/or telephone follow-up. There were eight patients lost to follow-up. Patients who were lost during the follow-up period were censored at the last time of contact. Median time from date of surgery to last contact for the patients was 62 months (range 8–153 months).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 20.0, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Mean values are presented as mean ± standard deviation, and categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. Ranked data were evaluated using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Efficacy of EUS in classifying T category was evaluated by assessing sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value (PPV), overstage rate, and understage rate compared with pT category as gold standard. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate overall survival (OS), and the log-rank test was used to assess survival differences between groups. Two-sided probability value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. OS was calculated from date of surgery to date of death or last available follow-up.

Results

General Patient Characteristics

In total, 1434 patients were included in the study. Their clinicopathological characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The patients ranged in age from 35.0 to 84.0 years (median, 59.0 years), and 76.2% were male. The lower third of the esophagus was the most common location of tumor occurrence in this study, and T3 cases accounted for the majority of cases (Table 1).

Efficacy of EUS in Classifying Clinical T Category

Compared with pT category, the overall sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, PPV, overstage rate, and understage rate of EUS in classifying T category were 58.2, 79.5, 72.7, 58.2, 17.9, and 23.9%, respectively. Detailed comparisons between uT and pT categories are presented in Tables 2 and 3. EUS had the highest sensitivity (65.8%) and PPV (85.9%) in pT3 patients (Table 3). However, note that as many as 31.1% (298/958) of pT3 patients were understaged as having uT2 lesions by EUS (Table 2). In pT2 cases, 56.8% were accurately classified (Table 3), but as many as 35.8% (87/243) were overstaged as uT3 lesions by EUS (Table 2). Unexpectedly, the PPV of EUS in classifying the T2 category was only 25.8% (Table 3), and 55.7% (298/535) of uT2 patients identified by EUS were understaged from pT3 cases (Table 2). With regard to Tis and T1 cases, our data showed that EUS had unsatisfactory sensitivity and high overstaging rates: 15.8 and 84.2% for Tis, 16.3 and 83.7% for T1a, and 33.1 and 56.9% for T1b, respectively (Table 3). It is interesting that nearly half of uT1a patients (46.9%, 15/32) were actually pT1b cases, but only 25.3% (25/99) of uT1b patients were actually pT1a cases (Table 2). It should also be noted that all 21 uT4b patients were actually pT3 (18 cases) and pT2 (3 cases), as assessed by the resected specimens (Table 2).

Survival Analysis Based on uT and pT Categories

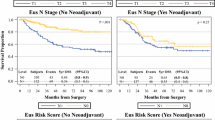

Perioperative mortality was 1.4% in the entire cohort. The long-term survival data for the pT and uT categories are listed in Table S1 (online only). As expected, the survival rate decreased monotonically and differed greatly with increasing T categories in both pT and uT category (Table S1, online only; Fig. 1). However, the long-term OS rate could not be clearly determined for T1a and T1b in either pT category (p = 0.93; Fig. 1a) or uT category (p = 0.90; Fig. 1b). Similar results were also observed between uT4a and uT4b patients (p = 0.34; Fig. 1b).

Since EUS could not clearly determine OS well for uT1a and uT1b, we integrated uT1a and uT1b into uT1. Likewise, uT4a and uT4b were integrated into uT4. Based on the integrated uT categories, the sensitivity and PPV of EUS for classifying T1 lesions increased to 49.3 and 76.3%, respectively (Table S3). Unfortunately, due to the small number of cases, the sensitivity and PPV of EUS for classifying the T4 category failed to improve (Table S3).

To evaluate the efficacy of the integrated uT category, the survival analyses were recalculated. As expected, the OS discrimination between the different T categories was dramatically improved (Table S4, online only; Fig. 2). Additionally, compared with pT categories, uT categories had similar corresponding 5-year survival rates, especially in T1–3 categories (Table S4, online only).

Efficacy of EUS at Different Tumor Locations

In further analysis, we divided all 1434 patients into three groups (upper third, middle third, and lower third), and analyzed the EUS performance between them. Detailed results are presented in Table S5. Interestingly, there was a statistically significant difference in EUS performance between different tumor locations (p = 0.01, Table S5, online only). EUS had the lowest sensitivity for upper-third tumors, but the highest sensitivity for lower-third tumors (39.7 vs. 60.4%, p < 0.01).

Discussion

These results show that EUS had moderate overall sensitivity (58.2%) and relatively high accuracy (72.7%) for classifying T category for ESCC. It is quite challenging for EUS to distinguish T1a from T1b tumors, and the PPV in classifying the T2 category is still not satisfactory. However, when the uT category was defined as uTis, uT1, uT2, uT3, and uT4, the OS could be clearly distinguished.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this report describes one of the largest studies evaluating the efficacy of EUS in determining T category for ESCC. The large number of cases included in the study lends power to assess the efficacy of EUS in classifying T categories and predicting OS based on uT categories in patients with ESCC. Our results suggest that, in general, EUS is useful in classifying T category for ESCC. Based on these findings, our data suggest that uT category determined by EUS can be used to guide the primary treatment for an individual patient with ESCC; For example, we can recommend preoperative chemoradiotherapy for ESCC patients if they are classified as T3 by EUS, because a previous report confirmed that this treatment strategy can benefit these patients.16 However, the primary treatment for cT2 category is controversial.17,18,19,20,21 Several studies recommend that patients with cT2 esophageal cancer should undergo esophagectomy without neoadjuvant therapy,17,18 while others suggest induction therapy because cT2 cases were usually understaged.19,20 Our results also showed that more than half of uT2 tumors were actually pT3 cases, suggesting that it is reasonable for uT2 patients to undergo induction therapy.

The latest metaanalysis including 42 studies (n = 2722) by Luo et al. concluded that the sensitivity of EUS in identifying T category was relatively high: 77% for T1, 66% for T2, 87% for T3, and 84% for T4 categories.22 Those researchers’ results were higher than ours. We could not determine a plausible explanation for this finding, other than that all of the EUS records were carefully reviewed. Interestingly, when their study was divided into two periods of time (1986–1999 and 2000–2014), they observed that the accuracy of EUS in determining T category was lower in 2000–2014 than in the last century (74 vs. 81%, p = 0.035).22 It is interesting that, comparing our results with those of Luo et al.’s subgroup from 2000 and 2014, the accuracy of EUS in defining T category is comparable. Recently, O’Farrell et al. presented 77 patients with esophageal cancer, demonstrating that the sensitivity of EUS in classifying T2 and T3 categories was 55 and 66%, respectively,8 highly similar to our results. However, the sensitivity of EUS in classifying the T1 category in their study was much higher than ours (94 vs. 49%). The small number of T1 cases in their study (33 cases) may account for this discrepancy. With regard to the T4 category, Meister et al. reported that the sensitivity of EUS was low (13%),9 which was quite similar to our results, indicating that EUS was not reliable in classifying the T4 category.

In further analysis, this study highlights the difficulty in distinguishing between T1a and T1b categories using EUS, which was also demonstrated by previous studies, due to the low sensitivity for T1a (31–39%) and T1b (51–56%).7,23 However, patients with T1a tumors are qualified candidates for receiving endoscopic resection,1,24,25,26 while patients with T1b tumors require esophagectomy.1,27 This indicates that it is desirable to improve the efficacy of EUS in distinguishing T1a and T1b by using more innovative techniques. Recently, Li et al. employed a novel technique (submucosal saline injection plus EUS) to stage early ESCC, and achieved high sensitivity for T1a (83.3%) and T1b (88.9%) tumors.28

The purpose of accurate staging is to predict patient survival prognosis and guide tailored therapy. Using data from the Worldwide Esophageal Cancer Collaboration, Rice et al. recently revealed that OS could be clearly determined using cT category.29 Unfortunately, a standard method was not defined for determining cT category, since the staging methods were inconsistent in their study.29 In this study, we used EUS alone to classify cT category, and the survival curves were, in general, clear between different uT categories, although due to the small number of uT4 tumors, discrimination of patient survival between uT3 and uT4 tumors was not satisfactory (p = 0.44). We therefore propose that more attention should be paid to distinguishing uT4 patients from other categories by EUS.

The limitations of this study should also be considered. First, as a retrospective study, diagnostic bias may exist because the EUS examinations were performed by different doctors, and their technique may be varied. Nevertheless, this may make our results more generalizable. Second, since patients with R1 and R2 resections were excluded, and most T4 cases underwent chemoradiotherapy, the number in the T4 subgroup was small. We believe further studies are warranted to draw a conclusion for T4 patients. Third, the results of this study were generated from a single institution, and we believe that more data from other centers, especially from Asia, are necessary to confirm our results.

The results of this study indicate that, in general, EUS is a feasible technique for determining cT category for ESCC. However, EUS should be used with caution for discriminating between Tis, T1a, and T1b disease, as well as T4 disease. More data from other centers are warranted to test our results.

References

Ajani JA, D’Amico TA, Almhanna K, et al. Esophageal and esophagogastric junction cancers, version 1.2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13:194-227.

Luo LN, He LJ, Gao XY, et al. Evaluation of preoperative staging for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:6683-6689.

Choi J, Kim SG, Kim JS, Jung HC, Song IS. Comparison of endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), positron emission tomography (PET), and computed tomography (CT) in the preoperative locoregional staging of resectable esophageal cancer. Surg Endosc 2010;24:1380-1386.

Blackshaw G, Lewis WG, Hopper AN, et al. Prospective comparison of endosonography, computed tomography, and histopathological stage of junctional oesophagogastric cancer. Clin Radiol 2008;63:1092-1098.

Thosani N, Singh H, Kapadia A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of EUS in differentiating mucosal versus submucosal invasion of superficial esophageal cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2012;75:242-253.

Puli S-R. Staging accuracy of esophageal cancer by endoscopic ultrasound: a meta-analysis and systematic review. World J Gastroenterol 2008;14:1479-1490.

Dhupar R, Rice RD, Correa AM, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound estimates for tumor depth at the gastroesophageal junction are inaccurate: implications for the liberal use of endoscopic resection. Ann Thorac Surg 2015;100:1812-1816.

O’Farrell NJ, Malik V, Donohoe CL, et al. Appraisal of staging endoscopic ultrasonography in a modern high-volume esophageal program. World J Surg 2013;37:1666-1672.

Meister T, Heinzow HS, Osterkamp R, et al. Miniprobe endoscopic ultrasound accurately stages esophageal cancer and guides therapeutic decisions in the era of neoadjuvant therapy: results of a multicenter cohort analysis. Surg Endosc 2013;27:2813-2819.

van Zoonen M, van Oijen MG, van Leeuwen MS, van Hillegersberg R, Siersema PD, Vleggaar FP. Low impact of staging EUS for determining surgical resectability in esophageal cancer. Surg Endosc 2012;26:2828-2834.

Bentrem D, Gerdes H, Tang L, Brennan M, Coit D. Clinical correlation of endoscopic ultrasonography with pathologic stage and outcome in patients undergoing curative resection for gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2007;14:1853-1859.x

Barbour AP, Rizk NP, Gerdes H, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound predicts outcomes for patients with adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction. J Am Coll Surg 2007;205:593-601.

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015;136:E359-386.

Lin Y, Totsuka Y, He Y, et al. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer in Japan and China. J Epidemiol 2013;23:233-242.

Rice TW, Ishwaran H, Ferguson MK, Blackstone EH, Goldstraw P. Cancer of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction: an eighth edition staging primer. J Thorac Oncol 2017;12:36-42.

van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2074-2084.

Markar SR, Gronnier C, Pasquer A, et al. Role of neoadjuvant treatment in clinical T2N0M0 oesophageal cancer: results from a retrospective multi-center European study. Eur J Cancer 2016;56:59-68.

Speicher PJ, Ganapathi AM, Englum BR, et al. Induction therapy does not improve survival for clinical stage T2N0 esophageal cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2014;9:1195-1201.

Dolan JP, Kaur T, Diggs BS, et al. Significant understaging is seen in clinically staged T2N0 esophageal cancer patients undergoing esophagectomy. Dis Esophagus 2016;29:320-325.

Hardacker TJ, Ceppa D, Okereke I, et al. Treatment of clinical T2N0M0 esophageal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:3739-3743.

Zhang JQ, Hooker CM, Brock MV, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy is beneficial for clinical stage T2 N0 esophageal cancer patients due to inaccurate preoperative staging. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;93:429-435.

Luo LN, He LJ, Gao XY, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound for preoperative esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0158373.

Bergeron EJ, Lin J, Chang AC, Orringer MB, Reddy RM. Endoscopic ultrasound is inadequate to determine which T1/T2 esophageal tumors are candidates for endoluminal therapies. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;147:765-771.

Pech O, May A, Manner H, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of endoscopic resection for patients with mucosal adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Gastroenterology 2014;146:652-660.

Berry MF, Zeyer-Brunner J, Castleberry AW, et al. Treatment modalities for T1N0 esophageal cancers: a comparative analysis of local therapy versus surgical resection. J Thorac Oncol 2013;8:796-802.

Bergman JJGHM, Zhang Y-M, He S, et al. (2011) Outcomes from a prospective trial of endoscopic radiofrequency ablation of early squamous cell neoplasia of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 74: 1181-1190.

Pennathur A, Farkas A, Krasinskas AM, et al. Esophagectomy for T1 esophageal cancer: outcomes in 100 patients and implications for endoscopic therapy. Ann Thorac Surg 2009;87:1048-1054.

Li JJ, Shan HB, Gu MF, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound combined with submucosal saline injection for differentiation of T1a and T1b esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a novel technique. Endoscopy 2013;45:667-670.

Rice TW, Apperson-Hansen C, DiPaola LM, et al. Worldwide esophageal cancer collaboration: clinical staging data. Dis Esophagus 2016;29:707-714.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Guangdong Esophageal Cancer Institute Science and Planning Foundation (M201401), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81501986), Guangdong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (2016A030313857), Guangdong Provincial Medical Scientific Funds (2016114134515565), and Guangdong Provincial Science and Technology Planning Foundation (2013B021800147).

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, J., Luo, GY., Liang, RB. et al. Efficacy of Endoscopic Ultrasonography for Determining Clinical T Category for Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Data From 1434 Surgical Cases. Ann Surg Oncol 25, 2075–2082 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-018-6406-9

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-018-6406-9