Abstract

Background

To assess whether extending the observation period in patients with a near clinical complete response (near cCR) after chemoradiation (CRT) leads to an impaired oncological outcome.

Methods

Patients who had a clinical complete response (cCR) 8–10 weeks after CRT restaging with magnetic resonance imaging and endoscopy were offered a watch-and-wait strategy (W&W1), while patients with a near cCR were offered to undergo local excision or a second restaging 6–12 weeks later. Patients who achieved a cCR at the second restaging were also offered a watch-and-wait strategy (W&W2).

Results

Overall, 102 patients with a cCR at the first restaging immediately entered the W&W1, while the remaining 68 patients had a near cCR: 19 patients underwent transanal endoscopic microsurgery and 49 patients opted for a second restaging. Additionally, 44/49 (90%) patients showed a cCR at the second restaging and entered the W&W2. Patients in the W&W1 group had a 2-year local regrowth-free rate (LRFR) of 84% and 2-year overall survival (OS) of 99%, while patients in the W&W2 group had a 2-year LRFR of 73% and OS of 98% (p > 0.05). Multivariable Cox regression analyses showed that late inclusion was not a significant predictive factor for higher risk of LR or lower non-regrowth disease-free survival.

Conclusions

Overall, 90% of patients with a near cCR 8–10 weeks after CRT will proceed to a cCR 6–12 weeks later; therefore, it seems logical to extend the observation period rather than to proceed to surgery. Although there is a non-significant increase in local regrowth rate in these patients, it does not seem to impact the oncological outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Patients with locally advanced rectal cancer are treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiation (CRT) followed by total mesorectal excision (TME), typically after 6–10 weeks. In 15–20% of these patients, histopathology shows no residual tumor.1 Organ preservation (watch-and-wait [W&W] policy) could be offered to clinical complete responders (cCRs) after neoadjuvant CRT as an alternative for resection, mainly because of an improved quality of life and good oncological outcome.2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 The interest in this approach is increasing and there is a shift from a very strict selection strategy, including only patients when all diagnostic procedures show an unequivocal complete response, towards a less strict approach in which organ preservation is also considered in the so-called clinical near-complete responders (near cCR). On endoscopy and MRI, these patients still have some minor or equivocal findings and a local excision is often advocated to determine the final response. Although the oncological results of local excision after CRT in near cCR are reported to be good, substantial morbidity is associated with the procedure.10,11,12,13,14 Another approach to determine whether or not these near cCRs are, in reality, complete responders is to extend the observation period. A longer interval after CRT has been shown to result in more patients with a cCR.15 With a second assessment after another 6- to 12-week interval in patients with a near cCR, an additional number of patients were expected to show a cCR that can be managed by a W&W policy, while patients with residual abnormalities can undergo additional treatment.15

The question arises as to whether patients who achieve a complete response after a prolonged interval between CRT and response assessment have a higher risk for local regrowth and/or distant metastasis in a W&W policy than patients who immediately have a complete response. Therefore, the aim of this study was to compare the outcome of patients selected for a W&W policy at restaging 8–10 weeks after CRT with that of patients selected after a second restaging after an additional 6- to 12-week observation period.

Methods

Patients

This study included a highly selected group of all rectal cancer patients who were evaluated as potential candidates for a W&W strategy after neoadjuvant CRT between January 2005 and August 2015, including both patients who were primarily treated at our institute and patients who were referred. Organ preservation was offered in a prospective cohort study, approved by the local Institutional Review Board and registered in ClinicalTrials.gov since 2009 (NCT00939666 and NCT02278653). Inclusion criteria were non-metastatic biopsy-proven rectal cancer, neoadjuvant treatment (long course of CRT or 5 × 5 Gy radiotherapy with a long waiting interval), and evidence of a cCR or near cCR (definitions described below). Follow-up data were available for a period of ≥ 12 months after inclusion for W&W.

Post-chemoradiotherapy Evaluation

All patients underwent post-CRT restaging 8–10 weeks after the last radiation, with digital rectal examination (DRE), endoscopy, and magnetic resonance imaging [MRI; including diffusion-weighted (DWI)-MRI]. This was either primarily performed in our hospital or repeated in our hospital in referred patients. DRE and endoscopy were performed by surgeons with expertise in response evaluation. A typical cCR on endoscopy was defined as a white scar with telangiectasia without palpable abnormalities.3,8 Biopsy was not mandatory but, when performed, should be negative. A clinical near-complete response (near cCR) was defined as a superficial soft irregularity at DRE, a small residual flat ulcer, or irregular wall thickening at endoscopy and/or dysplasia at histopathology. A cCR on DWI-MRI was defined as the absence of residual tumor on T2W-MRI, with low signal at the former tumor location on b1000 DWI-MRI and the absence of suspicious nodes on T2W-MRI.3,8 A near cCR was defined as obvious downstaging with/without residual fibrosis, but with a heterogeneous or irregular aspect on MRI and/or a small focal area of high signal on b1000 DWI-MRI. All MRIs were evaluated by radiologists with ≥ 5 years of specific expertise in rectal cancer imaging.

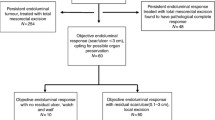

Decision for Watch-and-Wait Policy

From 2005 to 2009, patients were restaged 8–10 weeks after CRT. Patients who had an unequivocal cCR were offered a W&W policy. During 2009–2011, this approach shifted and in addition to patients with an immediate cCR 8–10 weeks after CRT (W&W1), patients with a near cCR were also offered to undergo either a local excision or a second restaging after an additional 6- to 12-week waiting interval. We initially used a 6-week interval but only a minor change in the clinical image was observed after 6 weeks, therefore we later changed this interval to 12 weeks. Patients who achieved a cCR at the second restaging were then offered a W&W policy (W&W2). All patients who did not obtain a cCR at the second restaging underwent a TME (see Fig. 1 for the patient flowchart). With all patients eligible for a W&W policy a TME was discussed as being the standard treatment.

Patient flowchart. First restaging: MRI and endoscopy, 8–10 weeks after the end of chemoradiation therapy. Second restaging: MRI and endoscopy, 6–12 weeks after the first restaging. cCR clinical complete response, cnCR near-complete response, W&W1 entering watch-and-wait protocol after first restaging, W&W2 entering watch-and-wait protocol after second restaging, TEM transanal endoscopic microsurgery, TME total mesorectal excision

Follow-Up

Additional to standard follow-up, according to national guidelines for colorectal cancer (consisting of regular carcinoembryonic antigen testing and computed tomography of the thorax and abdomen), patients underwent follow-up examinations specific for organ preservation, i.e. DRE, flexible sigmoidoscopy, and MRI 3-monthly in the first year and 6-monthly thereafter, as described previously.3,8

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared between groups using the independent samples t test for continuous variables and the χ 2 test for categorical variables. The interval between CRT and restaging was calculated from the last day of CRT to the first restaging in patients in the W&W1 group and to the second restaging in the W&W2 group.

Two-year local regrowth-free rate (LRFR), non-regrowth disease-free survival (NRDFS), and overall survival (OS) were calculated using Kaplan–Meier survival methods. Differences in survival between groups were tested using the log-rank test. OS was defined as the absence of death, LRFR was defined as the absence of luminal or nodal regrowth, and NRDFS was defined as the absence of death and distant metastasis. Duration of follow-up was calculated from the last date of radiotherapy to the event of interest or the last follow-up date.

A multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis was performed with the following factors: primary stage, age, sex, W&W1 versus W&W2, and adjuvant chemotherapy. Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). A p value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

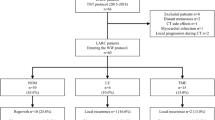

Baseline patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Overall, 170 patients had a cCR or near cCR after CRT; 141/170 patients (83%) were referred from 32 other hospitals.

Clinical Complete Responders

A total of 102 patients (60%) had a cCR at first restaging 8–10 weeks after CRT and opted for a W&W strategy (W&W1 group). The median time between CRT and restaging was 9 weeks (range 4–21 weeks).

Clinical Near-Complete Responders

Sixty-eight patients (40%) had a near cCR, of whom 28 (41%) had a near cCR due to a suspected small residual tumor on both MRI and endoscopy; 11 patients (16%) had suspected residual tumor at endoscopy, with a complete response on MRI; in 19 patients (28%) suspected residual tumor was seen on MRI, with a complete response at endoscopy; the remaining 10 patients (15%) had suspicious or uncertain nodes on MRI.

Of the 68 near cCR patients, 19 (28%) underwent transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM): 10 patients had ypT0, 3 had ypT1, and 6 had ypT2. The six patients with ypT2 tumors in the TEM specimen were offered completion TME but refused. The remaining 49 near cCR patients chose to wait longer and undergo a second restaging, which was performed after a median total interval of 23 weeks (range 13–49) from the final radiation dose. After this second restaging, 44/49 patients (90%) had a cCR and opted for a W&W policy (W&W2 group). The remaining five patients with clinical residual tumor underwent TME, with a ypT0N0 in one patient, ypT1N0 in two patients, and ypT3N1 in the remaining patients.

Local Regrowth and Survival

The median follow-up of patients in the W&W1 group was 26 months (5–136). The 2-year local regrowth-free rate (LRFR) was 84% (95% confidence interval [CI] 75–90), and 2-year NRDFS was 97% (95% CI 89–99). In addition, 2-year OS was 99% (95% CI 92–99.8) for the W&W1 group. Patients in the W&W2 group had a median follow-up of 19.5 months (range 6–103). Two-year LRFR was 73% (95% CI 55–85), NRDFS was 93% (95% CI 79–98), and OS was 98% (95% CI 85–99.7) (Fig. 2). Although LRFR was lower in the W&W2 group, there were no significant differences regarding long-term outcome (p = 0.237). The multivariate Cox regression analysis showed an increased hazard ratio for W&W2 for local regrowth (HR 1.43, 95% CI 0.64–3.22), although this was not statistically significant. Tables 2 and 3 show the survival results.

Fifteen patients in the W&W1 group had a local regrowth: 12 had a luminal regrowth (after a mean of 11 ± 5.7 months, 2 had a nodal regrowth (after a mean of 9.5 ± 5.0 months), and 1 patient had both a luminal and nodal regrowth (after 7 months). In the W&W2 group, 10 patients had a local regrowth, all intraluminal (after a mean of 12.8 ± 5.3 months). All patients (in both groups) could be salvaged with a TME (all R0 resections), i.e. the same surgical procedure that would have been performed if they had not participated in W&W. Three patients had postoperative complications from TME and one patient developed a recurrence after salvage TME.

In the 19 patients who underwent TEM, 4 patients had a luminal regrowth and 2 patients had lung metastasis. None of the ypT0 patients had a recurrence. From three ypT1 patients, one patient developed a luminal regrowth and one patient developed lung metastasis. Furthermore, from six ypT2 patients, three patients (50%) had a luminal regrowth and one patient had lung metastasis.

Discussion

This study shows that the majority of patients (90%) with a near cCR response 8–10 weeks after CRTof rectal cancer will evolve into a cCR at a second reassessment 6–12 weeks later. Allowing a longer interval for near cCR will increase the number of patients who can be offered W&W, avoiding unnecessary surgery in more patients. There was an increase in local regrowth rate in these patients, but this does not seem to lead to significantly worse NRDFS and OS.

The initial selection strategy for complete responders for W&W was very strict, leading to a low number of regrowths, but many complete responses were missed.3,16 The ‘test of time concept’ in the current study increased the number of patients eligible for W&W by 43%. This ‘test of time’ approach was also proposed by Smith et al., who first evaluated patients 6–7 weeks after CRT, followed by a second evaluation at 12 weeks for patients with major responses that fell slightly short of criteria for a typical cCR.4 The 1-year observation period as applied in earlier reports from Habr-Gama et al. can also be seen as an extended observation period, as is the ‘deferral of surgery’ concept of the Royal Marsden UK trial.2,17 The goal of these different approaches is to maximize the detection of complete responders. The underlying idea is that our current diagnostic techniques are insufficiently accurate to detect a true complete response because the rectal mucosa and wall can still be healing. Patients in the present study who were labeled as near cCR had presumed residual disease on MRI in approximately 84% of cases, and residual mucosal abnormalities at endoscopy in 57% of cases. Residual mucosal abnormalities as an important reason for missed cCR was also reported by Nahas et al.18 In a study on TME specimens, 74% of the ypT0 tumors showed mucosal lesions, mostly ulcers.4 Our study showed that in the large majority of patients, these features suggestive of residual disease disappeared after an extended interval. Several studies showed that the ability to detect a cCR is low for MRI as a single diagnostic modality (18–35%)18,19 and moderate for endoscopy (53%).20,21,22 Combining both increases sensitivity to 71%, meaning that 29% of the complete responses are still missed.18 The diagnostic performance of the modalities to predict whether a near cCR might become a cCR is yet to be determined.

Many retrospective studies have evaluated the impact of the interval after CRT on the pathological complete response (pCR) rate after surgery. A recent meta-analysis showed that the percentage of pCR after surgery increases by 6% when comparing intervals of less than 6–8 weeks with intervals of greater than 6–8 weeks.23 Sloothaak et al. reported an initial steep increase in response from 4 weeks after CRT, leveling off and reaching a plateau at 10–11 weeks.15 The single randomized trial GRECCAR 6 reported only a very small and non-significant difference in pCR between an interval of 7 versus 11 weeks.24 Although it seems there is little to gain with regard to increasing the pCR rate by extending the interval any longer, the clinical image of cCR lags behind and can lead to surgery being performed, while the patient will actually achieve a CR. This is confirmed by the observation that after an additional interval of only 6 weeks, only minor change in the clinical image was seen.

From a practical point of view, the traditional assessment 6–8 weeks after completion of CRT is a good starting point. Most patients will have obvious residual tumor that requires surgery. A local excision can be considered in special circumstances or in patients with substantial comorbidity. Some patients will present with a cCR, and the option of W&W can be offered as an alternative to TME. For patients with a near cCR, a reasonable option is to extend the observation period by another 12 weeks because the majority of these patients proceed to a cCR. One of the main concerns with extending the observation period is the risk of local tumor progression and the development of distant metastases in patients who do not reach a cCR. To date, the experience is that rapid local tumor progression in this short time span is virtually non-existent in patients with a near cCR, and that the originally planned TME is possible when eventually required. Although the current study is underpowered to draw conclusions in this respect, no statistically significant negative impact of a second observation period was noted on distant recurrence. The meta-analysis of studies comparing short and long intervals with surgery does not suggest any detrimental effect on survival of prolonging the interval.25 Overall, the risk for additional metastatic disease during a 12 week period in patients with a near cCR is expected to be very small.

The alternative to an additional observation period in near cCR is a local excision; however, this may result in postoperative morbidity, wound dehiscence, and pain.12 Additionally, there are reports that functional results are inferior compared with patients in a W&W strategy.22 A local excision does provide a definitive answer regarding the presence of residual tumor, and enables organ preservation in patients with a small tumor remnant.26

Another approach to maximize response is to use the interval for so-called ‘consolidation chemotherapy’. This approach has two potential advantages: (1) early chemotherapy could improve prognosis by tackling potential distant micrometastases; and (2) systemic chemotherapy combined with the prolonged interval may lead to a higher number of cCRs. This approach is supported by studies that have shown an increased pCR rate of 31–38% when chemotherapy is administered after neoadjuvant CRT.1,27,28

Limitations

This study had some limitations. First, the follow-up is rather short to provide reliable long-term estimates of NRDFS and OS. Second, the sample size is small and therefore it is impossible to draw any definite conclusions about a difference in the potential risk for distant recurrence between the two groups with different observation intervals. Third, the population consists of a highly selected patient group who were referred to our unit for further management with an already established good clinical response at the referring hospital. In an effort to correct for this potential bias, the two groups were strictly based on the interval of the post-CRT assessment that led to the decision for a W&W policy, irrespective of whether this was done at the referring center or our own center; however, this has led to overlap in the intervals to restaging between the groups.

Conclusions

The large majority of patients with a near cCR 8–10 weeks after CRT will evolve into a cCR by extending the observation period after CRT, and can be included in a W&W policy. These patients may have a higher local regrowth rate compared with initially clinical complete responders, but without an apparent impact on OS. All regrowths could be easily salvaged. Therefore, extending the interval in near cCRs in order to increase the number of patients who can benefit from organ preservation appears to be safe.

References

Maas M, Nelemans PJ, Valentini V, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with a pathological complete response after chemoradiation for rectal cancer: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11(9):835–44.

Habr-Gama A, Perez RO, Nadalin W, et al. Operative versus nonoperative treatment for stage 0 distal rectal cancer following chemoradiation therapy: long-term results. Ann Surg 2004; 240(4):711–7; discussion 717-8.

Maas M, Beets-Tan RG, Lambregts DM, et al. Wait-and-see policy for clinical complete responders after chemoradiation for rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29(35):4633–40.

Smith JD, Ruby JA, Goodman KA, et al. Nonoperative management of rectal cancer with complete clinical response after neoadjuvant therapy. Ann Surg 2012; 256(6):965–72.

Ayloor SR KS, Jayanand SB, et al. Complete clinical response to neoadjuvant chemoradiation in rectal cancers: can surgery be avoided? Hepatogastroenterology 2013;60(123):410–414.

Appelt AL, Ploen J, Harling H, et al. High-dose chemoradiotherapy and watchful waiting for distal rectal cancer: a prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol 2015;16(8):919–927.

Renehan AG, Malcomson L, Emsley R, et al. Watch-and-wait approach versus surgical resection after chemoradiotherapy for patients with rectal cancer (the OnCoRe project): a propensity-score matched cohort analysis. Lancet Oncol 2016;17(2):174–83.

Martens MH, Maas M, Heijnen LA, Lambregts DM, Leijtens JW, Stassen LP, et al. Long-term outcome of an organ preservation program after neoadjuvant treatment for rectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djw171.

Beets GL, Figueiredo NF, Beets-Tan RG. Management of Rectal Cancer Without Radical Resection. Annu Rev Med 2017;68:169–182.

Lezoche G, Baldarelli M, Guerrieri M, et al. A prospective randomized study with a 5-year minimum follow-up evaluation of transanal endoscopic microsurgery versus laparoscopic total mesorectal excision after neoadjuvant therapy. Surg Endosc 2008; 22(2):352–8.

Perez RO, Habr-Gama A, Sao Juliao GP, et al. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) following neoadjuvant chemoradiation for rectal cancer: outcomes of salvage resection for local recurrence. Ann Surg Oncol 2016;23(4):1143–8.

Perez RO, Habr-Gama A, Sao Juliao GP, et al. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery for residual rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy is associated with significant immediate pain and hospital readmission rates. Dis Colon Rectum 2011; 54(5):545–51.

Coco C, Rizzo G, Mattana C, et al. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery after neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy for locally advanced extraperitoneal rectal cancer: short-term morbidity and functional outcome. Surg Endosc 2013; 27(8):2860–7.

Garcia-Aguilar J, Renfro LA, Chow OS, et al. Organ preservation for clinical T2N0 distal rectal cancer using neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and local excision (ACOSOG Z6041): results of an open-label, single-arm, multi-institutional, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16(15):1537–46.

Sloothaak DA, Geijsen DE, van Leersum NJ, et al. Optimal time interval between neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and surgery for rectal cancer. Br J Surg 2013; 100(7):933–9.

Maas M, Lambregts DM, Nelemans PJ, et al. Assessment of clinical complete response after chemoradiation for rectal cancer with digital rectal examination, endoscopy, and MRI: selection for organ-saving treatment. Ann Surg Oncol 2015; 22(12):3873–80.

West MA, Dimitrov BD, Moyses HE, et al. Timing of surgery following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer—a comparison of magnetic resonance imaging at two time points and histopathological responses. Eur J Surg Oncol 2016; 42(9):1350–8.

Nahas SC, Rizkallah Nahas CS, Sparapan Marques CF, et al. Pathologic complete response in rectal cancer: can we detect it? Lessons learned from a proposed randomized trial of watch-and-wait treatment of rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2016;59(4):255–63.

Hughes R, Harrison M, Glynne-Jones R. Could a wait and see policy be justified in T3/4 rectal cancers after chemo-radiotherapy? Acta Oncol 2010; 49(3):378–81.

Nakagawa WT, Rossi BM, de OFF, et al. Chemoradiation instead of surgery to treat mid and low rectal tumors: is it safe? Ann Surg Oncol 2002;9(6):568–73.

Lim L, Chao M, Shapiro J, et al. Long-term outcomes of patients with localized rectal cancer treated with chemoradiation or radiotherapy alone because of medical inoperability or patient refusal. Dis Colon Rectum 2007; 50(12):2032-9.

Habr-Gama A, Lynn PB, Jorge JM, et al. Impact of organ-preserving strategies on anorectal function in patients with distal rectal cancer following neoadjuvant chemoradiation. Dis Colon Rectum 2016; 59(4):264–9.

Habr-Gama A, de Souza PM, Ribeiro U, Jr., et al. Low rectal cancer: impact of radiation and chemotherapy on surgical treatment. Dis Colon Rectum 1998;41(9):1087–96.

Lefevre JH, Mineur L, Kotti S, et al. Effect of interval (7 or 11 weeks) between neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy and surgery on complete pathologic response in rectal cancer: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial (GRECCAR-6). J Clin Oncol 2016;34:3773–3780.

Petrelli F, Sgroi G, Sarti E, et al. Increasing the interval between neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and surgery in rectal cancer: a meta-analysis of published studies. Ann Surg 2016; 263(3):458–64.

Creavin B, Ryan E, Martin ST, et al. Organ preservation with local excision or active surveillance following chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2017;116(2):169–174.

Huang CM, Huang MY, Tsai HL, et al. An observational study of extending FOLFOX chemotherapy, lengthening the interval between radiotherapy and surgery, and enhancing pathological complete response rates in rectal cancer patients following preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2016; 9(5):702-12.

Garcia-Aguilar J, Chow OS, Smith DD, et al. Effect of adding mFOLFOX6 after neoadjuvant chemoradiation in locally advanced rectal cancer: a multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16(8):957–66.

Disclosures

Britt J. P. Hupkens, Monique Maas, Milou H. Martens, Marit E. van der Sande, Doenja M. J. Lambregts, Stéphanie O. Breukink, Jarno Melenhorst, Janneke B. Houwers, Christiaan Hoff, Meindert N. Sosef, Jeroen W. A. Leijtens, Maaike Berbee, Regina G. H. Beets-Tan, and Geerard L. Beets have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

No funding or grants were used to assist in the preparation of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hupkens, B.J.P., Maas, M., Martens, M.H. et al. Organ Preservation in Rectal Cancer After Chemoradiation: Should We Extend the Observation Period in Patients with a Clinical Near-Complete Response?. Ann Surg Oncol 25, 197–203 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-017-6213-8

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-017-6213-8