Abstract

Background

Success factors of laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy (LNRH) to preserve bladder function are little known despite its widespread use. Thus, we conducted a protocol-based prospective cohort study to evaluate clinicopathologic factors for preserving autonomic nerves and its impact on duration of postoperative catheterization (DPC).

Methods

From 2012 to 2014, 30 patients with stage IB1 to IIA2 cervical cancer were recruited prospectively to undergo LNRH. All procedures were performed on the left side of the patients by one gynecologic oncologist. Extent of resection and preservation of autonomic nerves were documented in the protocol during LNRH.

Results

All patients received laparoscopic type C1 radical hysterectomy, where extent of resection and preservation of autonomic nerves were not different between the right and left sides. Stage IB1 disease was associated with the reduced risk of injury of the left junctions between the hypogastric and the splanchnic nerves; between the splanchnic nerve and the vesical branch of the pelvic plexus (S–V junction) (adjusted odds ratios, 0.06 and 0.06; 95 % confidence intervals, 0.01–0.92 and 0.01–0.48); the right S–V junction with marginal significance (adjusted odds ratio, 0.18; 95 % confidence interval, 0.03–1.06). Furthermore, bilateral preservation of autonomic nerves decreased DPC significantly when compared with failure or unilateral preservation (median, 6 days vs. 34 days or 57 days; P < 0.05).

Conclusions

LNRH has a higher likelihood of its success in stage IB1 than in stage IB2 to IIA disease. Moreover, preservation of bilateral autonomic nerves reduces DPC significantly in comparison with failure or unilateral preservation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Conventional radical hysterectomy (CRH) is one of primary treatments for patients with early-stage cervical cancer. In the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for treating International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage IB1 to IIA2 cervical cancer, CRH is recommended mainly in stage IB1 or IIA1 disease with tumor size <4 cm, whereas radiotherapy is preferred in stage IB2 to IIA2 disease with bulky tumor (≥4 cm).1 However, CRH can be also considered as a primary treatment of stage IB2 to IIA2 disease because surgery without radiotherapy has a 5-year survival rate of 96 %, which is similar to the result in previous studies where adjuvant radiotherapy after surgery was used according to pathologic findings.2–6 Moreover, CRH is also meaningful in providing the possibility to avoid radiotherapy, thereby preventing radiotherapy-related complications.7

In spite of the clinical efficacy of CRH for patients with cervical cancer, it causes urinary dysfunctions, including bladder hypotonia, urinary incontinence, and abnormal sensation, in 12–85 % of patients.8–10 The reason for this is that the pelvic autonomic nerves are injured during CRH, which play a major role of the neurogenic control of urinary functions. Thus, nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy (NRH) has emerged in the last 30 years for decreasing postoperative urinary dysfunctions without compromising oncologic outcomes, and the feasibility and efficacy of NRH have been suggested in a growing number of studies.11 Furthermore, Schneider and colleagues have reported identification and preservation of the pelvic splanchnic nerves in the cardinal ligament during laparoscopic radical hysterectomy, and some relevant studies have suggested the feasibility and efficacy of laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy (LNRH) since then.12–15

However, there are some limitations to replacing CRH with NRH, as follows: no consensus on the nerve-sparing technique; and an unresolved concern about whether the efficacy of NRH on preservation of bladder function is different among failure, unilateral, and bilateral preservation of autonomic nerves. Thus, we made a protocol for LNRH according to relevant anatomic identification and performed a protocol-based prospective cohort study. In the current study, we evaluated the success rate and factors for preservation of autonomic nerves during LNRH and compared postoperative bladder function among failure, unilateral, and bilateral preservation of autonomic nerves in patients with cervical cancer.

Study Design

Protocol

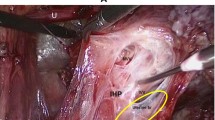

We reviewed anatomic identification of NRH as demonstrated in a previous study and then created a protocol for the current study (Supplementary Table 1).16 One experienced gynecologic oncologist performed LNRH on the left side of all patients according to Fujii’s method.16 Briefly, we found the hypogastric nerve containing sympathetic nerves on the rectal side of the pararectal space; the branch of the splanchnic nerve containing parasympathetic nerves was then identified after we cut the deep uterine vein in the deep portion of the parametrial connective tissue. Furthermore, we separated the anterior leaf of the vesicouterine ligament meticulously, and the posterior leaf of the vesicouterine ligament with the middle and inferior vesical veins was separated. We next identified the vesical branch of the pelvic plexus containing both sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves. In the protocol, LNRH-related structures for resection or preservation were demonstrated. Although the splanchnic nerve can be preserved easily if the deep uterine vein is identified and separated from the surrounding tissues, the junctions between the hypogastric and the splanchnic nerves (H–S junction) and between the splanchnic nerve and the vesical branch of the pelvic plexus (S–V junction) are easily injured by transection or thermal damage during dissection of the vesicouterine and uterosacral ligaments located in the proximal side of the uterus.17 Thus, we considered H–S and S–V junctions as the two points that should be preserved during LNRH in our protocol (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Comparison of duration of postoperative catheterization after laparoscopic nerve-sparing (type C1) radical hysterectomy among failure, unilateral, and bilateral preservation of junctions between hypogastric and splanchnic nerves (H–S junction) and between splanchnic nerve and vesical branch of pelvic plexus (S–V junction); *P < 0.05

Patients

We recruited patients with cervical cancer consecutively between September 2012 and April 2014. Eligibility criteria were as follows: FIGO stage IB1 to IIA2 disease; no previous abdominal surgery; no neoadjuvant chemotherapy; laparoscopic type C1 radical hysterectomy based on the Querleu-Morrow system; no abdominal disease hindering LNRH; documentation of the protocol during LNRH; and patients’ written informed consent.18 Among 40 patients who fulfilled the eligibility criteria during this period, 10 were excluded because of a finding of noncervical cancer at final pathology (n = 2), conversion to laparotomy (n = 2), loss of follow-up after surgery (n = 3), and incomplete documentation of the protocol (n = 3). Adjuvant concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) or CCRT followed by chemotherapy using cisplatin was administered to 14 patients (46.7 %) according to the following criteria: ≥2 intermediate-risk factors including tumor size ≥4 cm, stromal invasion ≥1/2, and lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI); or ≥1 high-risk factors including lymph node metastasis, parametrial invasion, and positive resection margin.

A Foley catheter was inserted until 2 days after surgery; all patients were then encouraged to void. We checked postvoid residual urine volume (PVR) after urination, and the patients were instructed to perform clean intermittent self-catheterization if PVR was less than 100 ml until 5 days after surgery. Thus, duration of postoperative catheterization (DPC) was defined as the time to achieve three consecutive PVRs of <100 ml after surgery.

Statistical Analysis

The main study outcomes were clinicopathologic factors for preserving autonomic nerves and DPC based on the degree of their preservation. We considered “not identified” or “thermal damage” as failure of preservation because it may increase the possibility of autonomic nerve injury. For identifying clinicopathologic factors to preserve autonomic nerves, we performed χ 2 or Fisher’s exact tests. After we selected potential factors on χ 2 or Fisher’s exact tests (P < 0.2), univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses with odds ratio (OR) and 95 % confidence interval (CI) were performed by using the potential factors. Moreover, power analysis was performed to demonstrate the effects of other covariates.

Next, we performed Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis tests for comparing DPC among failure, unilateral, and bilateral preservation of autonomic nerves. For statistical analyses, we used SPSS software version 19.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), and a P value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Preservation of Autonomic Nerves

Table 1 summarizes clinicopathologic characteristics of a total of 30 patients enrolled onto the current study. The median follow-up was 7.4 months (range, 3–20.6 months). No patient showed disease recurrence, and 5 patients (16.7 %) had surgery-related complications such as ureteral stricture, vesicovaginal fistula, urinoma, infected lymphocele, and lymphedema.

During LNRH, most of structures were resected according to the criteria of type C1 radical hysterectomy except the uterosacral ligament and length of the resected vagina and paracolpium due to intraoperative adhesion or bleeding.17 The uterosacral ligament was resected near the rectum in 18 patients (60 %), and length of the resected vagina of <1.5 cm and the paracolpium transected near S–V junction were observed in 4 (13.3 %) and 5 (16.7 %), respectively. However, there were no differences in extent of resection and preservation of autonomic nerves between the right and left sides (Table 2).

When we evaluated the success rate of preservation of H–S and S–V junctions according to clinicopathologic characteristics, the left H–S junction was preserved more commonly in stage IB1 disease (91.3 %) and no parametrial invasion (91.7 %) than in stage IB2 to IIA2 disease (57.1 %) and parametrial invasion (50 %), respectively. Moreover, we preserved the left S–V junction more frequently in stage IB1 than in IB2 to IIA2 disease (91.3 vs. 42.9 %), and it was preserved more commonly when the paracolpium was transected near the lower margin of the resected vagina (88 vs. 40 %; Table 3).

For evaluating independent factors for preservation of autonomic nerves, we selected stage IB1 disease, pelvic lymphadenectomy only, enough paracolpium, no LVSI, no lymph node metastasis, no parametrial invasion, negative resection margin, operative time <270 min and no transfusion as potential factors (P < 0.2), and then performed univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. We found that stage IB1 disease was related to a reduced risk of injury of left H–S (power 72.3 %; OR 0.06; 95 % CI 0.01–0.92) and left S–V junctions (power, 71.1 %; OR 0.06; 95 % CI 0.01–0.48). Moreover, it was also associated with a decreased risk of injury of the right S–V junction with marginal significance (power 73.7 %; OR 0.18; 95 % CI 0.03–1.06) (Table 4).

Duration of Postoperative Catheterization

When we compared DPC according to whether the H–S or S–V junction was injured, DPC was 82 days (range, 16–222 days), 38 days (range, 5–45 days), and 6 days (range, 3–34 days) in failure, unilateral, and bilateral preservation of H–S junction (P < 0.01), respectively. Among the 3 groups, we found a significant difference in DPC between failure and bilateral preservation. In terms of S–V junction, DPC was 57 days (range, 5–222 days), 34 days (range, 5–34 days), and 6 days (range, 3–12 days) in failure, unilateral, and bilateral preservation (P = 0.01), respectively, and it was different significantly between failure and bilateral preservation or between unilateral and bilateral preservation. For a comprehensive understanding of autonomic nerve function, we combined the data for both the H–S and S–V junctions and evaluated the impact of preservation of both junctions on recovery of postoperative bladder function. As a result, DPC was 57 days (range, 5–222 days), 34 days (range, 5–45 days) and 6 days (range, 3–12 days) in failure, unilateral, and bilateral preservation (P < 0.01), respectively. Among the 3 groups, DPC was significantly different between failure and bilateral preservation and between unilateral and bilateral preservation (Fig. 1).

Discussion

Generally, sympathetic nerves in the hypogastric nerve and the vesical branch of the pelvic plexus stimulate the urethral sphincter and inhibit the detrusor muscle of the bladder, whereas parasympathetic nerves in the splanchnic nerve and the vesical branch of the pelvic plexus relax the urethral sphincter and stimulate the detrusor muscle of the bladder.19 , 20 Because CRH causes pelvic autonomic dysregulation after surgical interruption, NRH has been the subject of interest because of its feasibility and safety.21 Depending on the development of the relevant anatomy, the hypogastric nerve can be separated from the uterosacral ligament, and the splanchnic nerve can be preserved during resection of the deep uterine vein and removal of the surrounding tissues called as the parametrium. Moreover, the vesical branch of the pelvic plexus can be separated from the paracolpium to remove a sufficient length of the vagina.16 , 22 Regarding its safety, NRH is expected to reduce postoperative bladder dysfunction without any decrease in radicality necessary to treat cervical cancer and to show a similar prognosis to CRH.23 , 24 However, no consensus of the nerve-sparing technique and an unresolved problem regarding the impact of the degree of preservation of autonomic nerves on postoperative bladder function are major limitations to change CRH into NRH as the primary treatment of cervical cancer.

In the current study, we found that FIGO stage IB1 disease was the only factor for enhancing the likelihood of the success of LNRH. Because there are few relevant studies, this finding is, to our knowledge, a new result for preserving autonomic nerves. It can be supported by a previous intention-to-treat study that showed a tendency for NRH to be performed more commonly in stage IB1 than in stage IB2 to IIA disease compared with CRH (77.7 vs. 67.7 %).25 This means that tumor extension to adjacent areas—stage IB2 to IIA2 disease—makes preservation of autonomic nerves by LNRH more difficult.

In particular, stage IB1 disease was an independent favorable factor for reducing the risk of injury of the left autonomic nerves, whereas it was related to the decreased risk of injury of the right S–V junction with marginal significance. The reason for this is that LNRH was performed in the left side of all patients. Actually, the surgeon experienced difficulty in preserving the right autonomic nerves because of the narrow range of motion with rigid instruments during laparoscopy. Preservation of autonomic nerves may thus be influenced by the surgeon’s position during LNRH. This hypothesis may be supported by the finding that the success rates of preservation of H–S and S–V junctions were lower in the right side than in the left side in stage IB1 disease (87 vs. 91.3 %; 78.3 vs. 91.3 %). Thus, we thought that stage IB1 disease could not be a favorable factor for preservation of the right side because of the relatively low rate of success. To overcome this limitation, it is important to perform LNRH on the side of the distribution of autonomic nerves or to replace it with robot-assisted NRH because of the wide range of motion required for wristed instruments.

Furthermore, bilateral preservation of autonomic nerves showed shorter DPC than failure or unilateral preservation. This finding is similar to previous studies in which unilateral preservation resulted in more damage to bladder function immediately after surgery than bilateral preservation.26 , 27 This means that failure or unilateral preservation may not play a role in preserving bladder function, as bilateral preservation does. However, further investigation is necessary to compare bladder function among failure, unilateral and bilateral preservation after surgery because previous studies have reported no difference between unilateral and bilateral preservation in long-term follow-up.28–30

The current study had the following advantages. First, some relevant studies have reported only the feasibility of NRH by many surgeons, without also reporting its success rate.14 , 15 , 25 , 29 We, however, conducted a protocol-based prospective cohort study where patients were recruited consecutively, and one gynecologic oncologist performed laparoscopic type C1 radical hysterectomy. Second, we reported the success rate of LNRH and found clinicopathologic factors affecting preservation of autonomic nerves. Third, we investigated postoperative bladder function according to the degree of preservation of autonomic nerves.

However, the current study has some limitations. The feasibility of laparoscopic radical surgery has not been established in clinical trials. However, we selected LNRH because it has been reported to be feasible in previous studies, and it has some advantages in terms of early recovery after surgery, short hospitalization, and a low rate complications compared with laparotomic NRH. Moreover, the feasibility of LNRH is expected to be evaluated by an ongoing clinical trial in the near future.31 Second, a growing body of literature supports the use of type B surgery in patients with stage IB1 disease.32 However, we prefer type C1 LRH because of a lack of well-designed randomized controlled trials to provide the safety and efficacy of type B surgery in the patients. Third, the small number of patients (thus contributing to the study’s relative low power, at <80 %), the incomplete resection of the uterosacral ligament and the paracolpium, as well as the length of the resected vagina bias the interpretation of the current study’s results.

However, the current study is meaningful in that LNRH may have a higher likelihood of its success in FIGO stage IB1 than in stage IB2 to IIA disease, and bilateral preservation of autonomic nerves may be more important to preserve bladder function immediately after surgery than failure or unilateral preservation. Further large protocol-based prospective study for LNRH are needed to approve these results.

References

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Cervical cancer practive guidelines in oncology, version 1, 2014. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#site. Accessed July, 2014.

Hockel M, Horn LC, Manthey N, et al. Resection of the embryologically defined uterovaginal (Mullerian) compartment and pelvic control in patients with cervical cancer: a prospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:683–92.

Hockel M, Hentschel B, Horn LC. Association between developmental steps in the organogenesis of the uterine cervix and locoregional progression of cervical cancer: a prospective clinicopathological analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:445–56.

Lee TY, Jeung YJ, Lee CJ, et al. Promising treatment results of adjuvant chemotherapy following radical hysterectomy for intermediate risk stage 1B cervical cancer. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2013;56:15–21.

Kim HS, Kim JY, Park NH, et al. Matched-case comparison for the efficacy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy before surgery in FIGO stage IB1–IIA cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;119:217–24.

Quinn MA, Benedet JL, Odicino F, et al. Carcinoma of the cervix uteri. FIGO 26th annual report on the results of treatment in gynecological cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;95(Suppl 1):S43–103.

Suh DH, Kim JW, Kang S, et al. Major clinical research advances in gynecologic cancer in 2013. J Gynecol Oncol. 2014;25:236–48.

Benedetti-Panici P, Zullo MA, Plotti F, et al. Long-term bladder function in patients with locally advanced cervical carcinoma treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and type 3–4 radical hysterectomy. Cancer. 2004;100:2110–7.

Chen GD, Lin LY, Wang PH, Lee HS. Urinary tract dysfunction after radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;85:292–7.

Zullo MA, Manci N, Angioli R, et al. Vesical dysfunctions after radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer: a critical review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2003;48:287–93.

Pieterse QD, Kenter GG, Maas CP, et al. Self-reported sexual, bowel and bladder function in cervical cancer patients following different treatment modalities: longitudinal prospective cohort study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23:1717–25.

Possover M, Stober S, Plaul K, Schneider A. Identification and preservation of the motoric innervation of the bladder in radical hysterectomy type III. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;79:154–7.

Querleu D, Narducci F, Poulard V, et al. Modified radical vaginal hysterectomy with or without laparoscopic nerve-sparing dissection: a comparative study. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;85:154–8.

Ceccaroni M, Roviglione G, Spagnolo E, et al. Pelvic dysfunctions and quality of life after nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy: a multicenter comparative study. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:581–8.

Bogani G, Cromi A, Uccella S, et al. Nerve-sparing versus conventional laparoscopic radical hysterectomy: a minimum 12 months’ follow-up study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24:787–93.

Fujii S. Anatomic identification of nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy: a step-by-step procedure. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:S33–41.

Dursun P, Ayhan A, Kuscu E. Nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy for cervical carcinoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2009;70:195–205.

Querleu D, Morrow CP. Classification of radical hysterectomy. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:297–303.

Raspagliesi F, Ditto A, Fontanelli R, et al. Type II versus type III nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy: comparison of lower urinary tract dysfunctions. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;102:256–62.

Rob L, Halaska M, Robova H. Nerve-sparing and individually tailored surgery for cervical cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:292–301.

Charoenkwan K, Pranpanas S. Prevalence and characteristics of late postoperative voiding dysfunction in early-stage cervical cancer patients treated with radical hysterectomy. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2007;8:387–9.

Bergmark K, Avall-Lundqvist E, Dickman PW, et al. Vaginal changes and sexuality in women with a history of cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1383–9.

Kim HS, Choi CH, Lim MC, et al. Safe criteria for less radical trachelectomy in patients with early-stage cervical cancer: a multicenter clinicopathologic study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:1973–9.

Landoni F, Maneo A, Cormio G, et al. Class II versus class III radical hysterectomy in stage IB–IIA cervical cancer: a prospective randomized study. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;80:3–12.

van den Tillaart SA, Kenter GG, Peters AA, et al. Nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy: local recurrence rate, feasibility, and safety in cervical cancer patients stage IA to IIA. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:39–45.

Kato K, Suzuka K, Osaki T, Tanaka N. Unilateral or bilateral nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy: a surgical technique to preserve the pelvic autonomic nerves while increasing radicality. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17:1172–8.

Tseng CJ, Shen HP, Lin YH, et al. A prospective study of nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy for uterine cervical carcinoma in Taiwan. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;51:55–9.

Liang JT, Chien CT, Chang KJ, et al. Neurophysiological basis of sympathetic nerve-preserving surgery for lower rectal cancer—a canine model. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:2206–14.

Chen C, Li W, Li F, et al. Classical and nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy: an evaluation of the nerve trauma in cardinal ligament. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:245–51.

Ditto A, Martinelli F, Mattana F, et al. Class III nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy versus standard class III radical hysterectomy: an observational study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:3469–78.

Laparoscopic approach to cervical cancer (LACC). Available at: http://www.clinicaltrial.gov/ct2/show/NCT00614211?term=LACC&rank=1. Accessed July, 2014.

Ditto A, Martinelli F, Ramondino S, et al. Class II versus class III radical hysterectomy in early cervical cancer: an observational study in a tertiary center. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:883–90.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants (04-2012-0890; 03-2012-0170) from the Seoul National University Hospital research fund and from the Priority Research Centers Program (2009-0093820) and BK21 plus program (5256-20140100) through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology. Members of the FUSION (FUnctional Surgery and Imaging On Neoplasms) Study Group: Hee Seung Kim, MD, Sang Youn Kim, MD, Min A. Kim, MD, PhD, Chang Wook Jeong, MD, PhD, Kyoung Sup Hong, MD, and Yong Sang Song MD, PhD (Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea).

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Behalf of the FUSION Study Group.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, H.S., Kim, T.H., Suh, D.H. et al. Success Factors of Laparoscopic Nerve-sparing Radical Hysterectomy for Preserving Bladder Function in Patients with Cervical Cancer: A Protocol-Based Prospective Cohort Study. Ann Surg Oncol 22, 1987–1995 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-014-4197-1

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-014-4197-1