Abstract

Total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy for cervical carcinoma is currently an accepted surgical procedure, however, bladder dysfunction after this procedure is likely to decrease the patient’s quality of life. Therefore, for a low risk of cervical carcinoma, total laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy should be applied.

In this chapter, step-by-step surgical instructions for total laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy are described (with a special focus on the nerve-sparing techniques) and our original research regarding the correlations between the preserved pelvic nerve networks and bladder functions after total laparoscopic nerve sparing radical hysterectomy are introduced.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy for cervical carcinoma is currently an accepted surgical procedure not only because of its technical feasibility, but also because of its favorable oncologic outcome [1–6]. However, bladder dysfunction after a laparoscopic radical hysterectomy is likely to decrease the patient’s quality of life because of the physical and mental stress that accompany post-operative disorders. The main cause is damage to the pelvic nerve plexus (inferior hypogastric plexus) and its vesical branches during this procedure. These nerve circuits are important for neurogenic bladder control [7–9].

Total laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy has been developed recently for early stage cervical carcinoma using a previously established technical procedure.. The principal features of this technique can be summarized by describing the procedure as one in which the hypogastric nerves, instead of the pelvic nerve plexus and its vesical branches, are preserved at several steps during a classical radical hysterectomy [10, 11]. Consequently, the hypogastric nerves are regarded as the main anatomical landmark of the nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy because they act as the upper limit of the pelvic nerve plexus and the vesical branches.

In this chapter, step-by-step surgical instructions for total laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy are described (with a special focus on the nerve-sparing techniques) and our original research regarding the correlations between the preserved pelvic nerve networks and bladder functions after total laparoscopic nerve sparing radical hysterectomy are introduced.

Surgical Procedures

Creation of the Vaginal Cuff

Prior to laparoscopic (LAP) surgery, a vaginal cuff is created (Fig. 41.1). In LAP surgery, an excision of suitable length of the vagina (2 cm from the tumor) is quite difficult due to the loss of tactile sensation; therefore, the creation of a vaginal cuff is essential for an accurate excision of the vagina. Moreover, the creation of a vaginal cuff is also quite useful to prevent the spillage of cancer cells during LAP surgery.

The patient is placed in the lithotomy position. First, 12–15 sutures are placed circumferentially approximately 2 cm from the tumor, and the sutures are pulled to reveal the incision line. Adrenaline at a dilution of 1:1,000,000 is injected into the incision line to reduce bleeding. The vaginal mucosa is then incised circumferentially using electrocautery and the vaginal cuff is doubly closed in a continuous fashion. When the margin of the tumor is difficult to determine, visual inspection with the Schiller test is essential.

Positioning of the Patient and Configuration of the Trocars

The patient is placed in the mild lithotomy position. The legs of the patient are extended slightly and the patent is tilted about 10 ° (Fig. 41.2a). A 12-mm trocar is placed in the umbilicus for a camera port and three 5-mm trocars for forceps are placed as in Fig. 41.2b. A 5-mm extra-long trocar (150 mm length) is placed at the posterior vaginal fornix, and a forceps placed through this port is used as a uterine manipulator. A 1-0 vicryl suture is placed around the uterine body and the uterus is manipulated by a pulling-and-pushing technique of the 1-0 vicryl suture with forceps through the vaginal trocar. In our procedure, a vaginal cuff is created prior to the LAP surgery, thus overcoming the problem of using a uterine manipulator (Fig. 41.2c).

Positioning of the patient and configuration of the trocars. (a) patient position, (b) trocar position, (c) A vaginal additional port. (C-1) An extra long trocar is placed at the posterior vaginal fornix. (C-2) 1-0 vicryl is placed around the uterine body. (C-3,4) This vicryl is grasped by the forceps through this port, and the uterus can be mobilized by this forceps like an uterine manipulator

Pelvic Lymphadenectomy

Pelvic lymphadenectomy is started by opening the pelvic sidewall triangle, which is the area between the round ligament, the infundibulopelvic ligament, and the external iliac vessels. At first, a wide opening of the pararectal space and paravesical space is developed allowing the exposure of the cardinal ligament between these spaces. These spaces are avascular spaces; therefore, a blunt dissection is sufficient for development. In order to maintain a good surgical view around the paravesical space (and obturator fossa), we suspend an umbilical ligament to the abdominal wall (Fig. 41.3 1).

Pelvic lymphadenectomy. (1) The umbilical ligament is suspended to the abdominal wall to maintain the good surgical view. (2) The space between the psoas muscle and the external iliac vessels is developed widely until the obturator nerve and vessels are exposed. (3) The upper end of the lymphofatty tissue(around the common iliac lesion) is clipped and transected. (4) Pelvic lymphnode is removed en block. (5, 6) Final view of pelvic lymphadenectomy

Next, the space between the psoas muscle and the external iliac vessels is developed widely in order to expose the obturator nerve and vessels (Fig. 41.3 2). The lymphofatty tissue is easily dissected from the obturator nerve and vessels using a blunt dissection technique and the upper end of the lymphofatty tissue (around the common iliac lesion) is clipped and transected (Fig. 41.3 3). The clipping of the cut end of lymph node is particularly important to prevent lymphocele after the surgery. Following the transection of the upper end, the lymphofatty tissue is easily stripped off the external and internal iliac vessels en block (Fig. 41.3 4–6).

For a total laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy, the complete exposure of the pelvic nerve networks (hypogastric nerves, pelvic splanchnic nerves, pelvic nerve plexus, and their vesical branches) is essential; and in order to achieve complete exposure it is very important to perform lymphadenectomy adjacent to the internal iliac region.

After developing a wide pararectal space, the hypogastric nerves can be observed easily along the lateral sides of the mesorectum. The lymph node tissue around the internal iliac region is removed completely; then, the S2–3 roots are identifiable beneath the fascia of the piriformis muscle. Additionally the pelvic splanchnic nerves, which join the pelvic nerve plexus, are visible as visceral branches originating from the S2–3 roots after the lymph node tissue around the cardinal ligament is meticulously removed (Fig. 41.4). After all lymph nodes are harvested, the nodes are removed with a plastic bag to prevent the scattering of the specimen.

Complete exposure of pelvic nerve networks. (1) The lymph node tissue around the internal iliac region is removed completely, then the S2–3 roots are identifiable beneath the fascia of the piriform muscle. (2) The complete structure of pelvic nerve plexus is marked by a dotted circle. They are consisted by hypogastric nerves and pelvic splanchnic nerves

The Transection of Upper Ligaments

The infundibulopelvic ligament or the adnexal ligament (if the patient wants to preserve her ovaries) is desiccated and transected. The round ligament is also desiccated and divided.

The Dissection of the Bladder

The bladder peritoneum is incised using a monopolar knife and the bladder is dissected from the cervix. When the bladder is lifted ventrally enough, an avascular area between the bladder and the cervix can be visualized, and then the dissection of the bladder can easily be performed.

The Transection of the Uterine Artery and the Unroofing of the Ureter

The uterine artery has already been isolated at the pelvic lymphadenectomy step described above; therefore, the transection of the uterine artery is easily performed using a hemoclip. Lifting the end of the uterine artery medially, a branch to the bladder (middle vesical artery) is isolated. After transecting this branch, the uterine artery can be isolated from the ureter completely, and the ureter tunnel can be developed median of the ureter. The bladder pillar is dissected meticulously thus allowing a small vessel to be isolated (cervico-vesical vessels). After transecting these cervico-vesical vessels, the unroofing of the ureter is accomplished.

Steps 4–6 are identical to those of total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy (non nerve-sparing techniques); therefore please refer to the relevant chapter for further details.

The Transection of the Cardinal Ligament

At the pelvic lymphadenectomy step described above, the lymph node of the cardinal ligament is removed; therefore, the vessels and nerves around the cardinal ligament are already isolated at this point. In nerve-sparing procedure described here, only the deep uterine vein is clipped and transected at the pelvic sidewall, and the stump of the deep uterine vein is scraped up to the level of the hypogastric nerves (i.e., the upper end of pelvic nerve networks).

The Transection of the Posterior Layer of the Vesico-Uterine Ligament

This step is essential for the preservation of the vesical branches of the pelvic nerve networks. At the posterior layer of the vesico-uterine ligament, the vesical vessels, nerves, and adipose tissue are packed by a membrane, therefore a meticulous dissection or “demembranation” is required to expose the two or three vesical veins, which flow into the deep uterine vein; these veins are clipped and transected. The remnant after the transection of these vesical vessels at the posterior layer of the vesico-uterine ligament contains the vesical branches of the pelvic nerve networks. For complete preservation of the function of vesical branches, it is essential to prevent thermal injury; therefore, the vesical veins are transected using clips and scissors (Fig. 41.5 1–4).

Transection of posterior layer of vesico-uterine ligament and paracolpium tissue. ① The posterior layer of vesico-uterine ligament of left side. Veins, nerves and adipose tissue are packed by a membrane.②③ “Demembranation” expose two or three vesical veins. They are isolated and transected one by one.④ After transection of the posterior layer of vesico-uterine ligament, pelvic nerve networks are exposed. (a) To preserved the pelvic nerve networks, the uterosacral ligament and paracolpium tissue are transected just above the hypogastric nerves. At this stage, we suture and ligate the paracolpium tissue to reduce the usage of energy device and to prevent thermal injury

Transection of the Paracolpium and Sacrouterine Ligament

The Douglas peritoneum is incised and the rectum is dissected until the posterior vaginal wall is exposed. Sometimes, the vaginal wall is opened at this stage because the vaginal cuff has already been created. After dissecting the rectum, the sacrouterine ligament can be exposed. To preserve the pelvic nerve networks, the uterosacral ligament and paracolpium tissue are transected just above the hypogastric nerves.

At this stage, the paracolpium tissue is sutured and ligated to reduce the usage of the energy device and to prevent thermal injury (Fig. 41.5a).

Transection of the Vagina

A vaginal pipe is inserted to extend the vaginal wall. The vaginal cuff has already been created at the first step of this surgery, thus after the transection of rectovaginal ligament, the vaginal wall can easily be transected.

Closure of the Vagina

The specimen is retrieved vaginally. To prevent the scattering of cancer cells, a plastic bag is used for the retrieval of the specimen (Fig. 41.6). The vaginal stump is closed using a 1-0 vicryl interrupted suture. The central part of the peritoneum is closed using a 2-0 vicryl suture, and the lateral part is opened to reduce the occurrence of lymphocyst following the surgery. The drainage tube is placed at the Douglas space.

The specimen of total laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy. ① To prevent the scattering of the cancer cells, a plastic bag is used for the retrieval of the specimen. ② This case is stage Ib2 cervical cancer, tumor size is 5 cm, and histological type is SCC. After the retrieval of the specimen, a vaginal cuff is opened to check the surgical margin

Figure 41.7 shows the final view of the total laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy for stage Ib2 cervical cancer.

Discussion

Bladder function following conventional total laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy is quite good. However, the degree of radicality of this procedure is insufficient in some cases. Therefore, the applicability of this procedure is expected to be limited to early stage cervical carcinoma [12]. For intermediate-stage or advanced-stage cervical carcinoma, a more radical procedure is necessary. In such cases, nerve-sparing techniques have never been applied. However, in some intermediate-risk cervical carcinoma cases, non-nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy tends to result in overtreatment. We suggest that a different nerve-sparing technique be applied for these cases.

The pelvic nerve plexus appears as a mesh and consists mainly of hypogastric nerves and pelvic splanchnic nerves. The hypogastric nerves are located at the ventral edge and pelvic splanchnic nerves are located at the dorsal edge of the pelvic nerve plexus [13]. Therefore, the pelvic nerve plexus has a somewhat definable anatomical width. In this case, it is possible to apply a different nerve sparing technique, which would likely consist of a more radical procedure than conventional nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy.

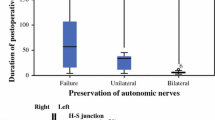

To accomplish the innovative nerve sparing technique described here, the complete exposure of the pelvic nerve plexus is necessary. As explained above, the complete exposure of pelvic nerve networks is possible and enables to control the degree of radicality to the point where the uterosacral ligament and paracolpium tissue can be transected. Furthermore, laparoscopic radical hysterectomies can be categorized into three types depending on the status of the preserved nerve network. The uterosacral ligament and the paracolpium tissue are transected above the hypogastric nerves for the conventional nerve-sparing procedure (group A), between the hypogastric nerves and pelvic splanchnic nerves for the radical nerve-sparing procedure (group B), or below the pelvic splanchnic nerves in the case of nerve-sacrificed radical hysterectomy (group C). We performed 27 cases belonging to group A, 13 cases to group B and 13 cases to group C (Fig. 41.8). Bladder function after these procedures was evaluated using urodynamic studies. Finally, we identified a correlation between the preserved pelvic nerve networks and bladder function after laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy.

The classification of total laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy. (a) Group A. (b) Group B (The dotted line shows the cutting line of Group A). (c) Group C. Patients with mixed pelvic nerve system sparing status (e.g., the right side is categorized into group A, and the left side is categorized into group C) were excluded from this study

Several studies have conducted urodynamic analyses after radical hysterectomy, but no consensus on these procedures has been reached, perhaps because around 80 % of patients with cervical carcinoma already had some degree of bladder dysfunction before the procedure was performed. It is therefore extremely difficult to evaluate the effects of nerve sparing techniques accurately [14]. In this study, we defined our original index (Function Ratio) to control for the scattering of data from urodynamic studies before surgical procedures. Urodynamic studies have many parameters, and among these parameters, the detrusor contraction pressure at maximum flow (PdetQmax) has been chosen to evaluate the motor function of the bladder, and the first desire to void (FDV) to evaluate sensory function, these are defined as:

Function Ratio (FDV) = FDV pre-operative / FDV post-operative.

Function Ratio (PdetQmax) = PdetQmax post-operative / PdetQmax pre-operative.

In fact, the PdetQmax is expected to be proportional to bladder function, and the FDV is expected to be inversely proportional to bladder function. Therefore, the function ratio formulas (FDV, PdetQmax) differ.

Ralph et al. reported that bladder function after radical hysterectomy could improve within 12 months after surgery [15]. Therefore, we analyzed data at 12 months after the operation to ascertain the correlation between the preserved pelvic nerve networks and bladder function after laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy (Fig. 41.9).

Based on the results of this study, it is possible to suggest that the distributions of sensory nerves and motor nerves differ. The sensory nerve is distributed predominantly at the lower (dorsal) half of the pelvic nerve networks. Thus, the sensory functions of group A and B are statistically equivalent, and the sensory function of group C is significantly lower than that of group A or B.

In contrast, the motor nerve is distributed predominantly at the upper (ventral) half of the pelvic nerve networks. Hence, the motor function of group A was significantly more preserved compared to that of either group B or C. The motor functions of groups B and C were damaged to same extent, and thus showed no mutually significant difference. Through this study, we conclude that various types of total laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy are technically feasible, and the sensory and motor functions of the bladder following the operation can be tailored depending on the patient’s risk of cervical cancer.

References

Malzoni M, Tinelli R, Cosentino F, Fusco A, Malzoni C. Total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy versus abdominal radical hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy in patients with early cervical cancer: our experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(5):1316–23.

Li G, Yan X, Shang H, Wang G, Chen L, Han Y. A comparison of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy and laparotomy in the treatment of Ib-IIa cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105(1):176–80.

Taylor SE, McBee Jr WC, Richard SD, Edwards RP. Radical hysterectomy for early stage cervical cancer: laparoscopy versus laparotomy. JSLS. 2011;15(2):213–7.

Lee EJ, Kang H, Kim DH. A comparative study of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy with radical abdominal hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer: a long-term follow-up study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;156(1):83–6.

Sobiczewski P, Bidzinski M, Derlatka P, Panek G, Danska-Bidzinska A, Gmyrek L, et al. Early cervical cancer managed by laparoscopy and conventional surgery: comparison of treatment results. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19(8):1390–5.

Nam JH, Park JY, Kim DY, Kim JH, Kim YM, Kim YT. Laparoscopic versus open radical hysterectomy in early-stage cervical cancer: long-term survival outcomes in a matched cohort study. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(4):903–11.

Glahn BE. The neurogenic factor in vesical dysfunction following radical hysterectomy for carcinoma of the cervix. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1970;4(2):107–16.

Seski JC, Diokno AC. Bladder dysfunction after radical abdominal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1977;128(6):643–51.

Fishman IJ, Shabsigh R, Kaplan AL. Lower urinary tract dysfunction after radical hysterectomy for carcinoma of cervix. Urology. 1986;28(6):462–8.

Kavallaris A, Hornemann A, Chalvatzas N, Luedders D, Diedrich K, Bohlmann MK. Laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy: description of the technique and patients’ outcome. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;119(2):198–201.

Liang Z, Chen Y, Xu H, Li Y, Wang D. Laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy with fascia space dissection technique for cervical cancer: description of technique and outcomes. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;119(2):202–7.

Park NY, Chong GO, Hong DG, Cho YL, Park IS, Lee YS. Oncologic results and surgical morbidity of laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy in the treatment of FIGO stage IB cervical cancer: long-term follow-up. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21(2):355–62.

Yamaguchi K, Kobayashi M, Kato T, Akita K. Origins and distribution of nerves to the female urinary bladder: new anatomical findings in the sex differences. Clin Anat. 2011;24(7):880–5.

Lin HH, Yu HJ, Sheu BC, Huang SC. Importance of urodynamic study before radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;81(2):270–2.

Ralph G, Tamussino K, Lichtenegger W. Urological complications after radical abdominal hysterectomy for cervical cancer. Baillieres Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 1988;2(4):943–52.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kanao, H., Takeshima, N. (2018). Total Laparoscopic Nerve-Sparing Radical Hysterectomy. In: Alkatout, I., Mettler, L. (eds) Hysterectomy. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-22497-8_41

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-22497-8_41

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-22496-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-22497-8

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)