Abstract

Background

Cerebellar malformations are broadly categorized into hypoplasias and dysplasias, which are further divided based on focal or diffuse involvement. Both hypoplasias and dysplasias are usually associated with cerebral involvement or as a part of syndromes. Isolated unilateral cerebellar dysplasia is, however, extremely unusual.

Case presentation

We present a rare case of isolated unilateral cerebellar dysplasia, in a 25-year-old male patient, who came to the Neurology clinic with complaints of infrequent seizure episodes since childhood.

Conclusion

Notable isolated unilateral cerebellar dysplasia is a rare entity requiring symptomatic treatment, with an anomalous development process being the likely aetiology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Abnormalities of human cerebellum are common features of development, but rarely persist in postnatal life [1,2,3]. Literature has reports of isolated mild cerebellar malformations, major cerebellar dysplasias are however very rare [1,2,3]. Few cases of major cortical cerebellar dysplasias have been reported in association with some congenital muscular dystrophies and related disorders, or intrauterine infections [3,4,5].Cerebellar malformations have also been observed together with cerebral abnormalities or as a component of syndromes like Joubert syndrome, Arima syndrome, Senior–Loken syndrome, Chudley–McCullough syndrome, CHARGE syndrome, and PHACES syndrome [6, 7]. Isolated unilateral cerebellar dysplasia is, however, exceedingly rare with only a few cases reported so far [1, 3, 6, 8]. We have summarized the literature review including a comparison with this case report (Table 1). Cerebellar developmental abnormalities have been attributed to aberrant migration and malorientation of the Purkinje cells and altered organization of glial cells in the intrauterine period as well as first 6–8 months of extra uterine life [1, 3, 9, 10]. According to a classification suggested by Patel and Barkovich, the malformations have been broadly classified into two types, malformations with cerebellar hypoplasia and ones with cerebellar dysplasia. Each of these was further classified into focal and diffuse [6]. Another classification has been suggested by P Demaerel, for cerebellar dysplasia, which was based on the part of the cerebellum which was involved. The dysplasias were divided into type 1a, in which the anterior lobe of the cerebellum showed abnormal fissuration, type 1b, in which dysplasia of both anterior and posterior lobe of the cerebellum was present, and type 2, which had vermian and hemispheric abnormalities [11]. It is pertinent to distinguish amongst the three developmental/intrauterine cerebellar abnormalities namely cerebellar atrophy, hypoplasia, and dysplasia. The term cerebellar atrophy refers to a small cerebellum with shrunken folia and large cerebellar fissures or a cerebellum that shows progressive volume loss. The term cerebellar hypoplasia is used for cases with a small cerebellum with fissures of normal size as compared to the folia [6]. The cerebellum is considered dysplastic if signs of disorganized development, such as an abnormal folial pattern or heterotopic nodules of gray matter are seen [6]. Defective or vertical fissures, irregular or bumpy gray–white matter junction, and abnormal arborization of the white matter within cerebellar hemispheres can also be seen. Vertical or abnormal fissures may also be present in the vermis [7]. Patients with cerebellar hypoplasia and dysplasia may present with seizure disorders, global or motor developmental delay, neurocognitive defects, hypotonia, or accompanying oculomotor disease, facial/skeletal deformities [1].

Case presentation

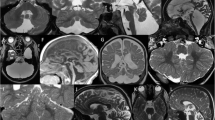

A 25-year-old male patient, presented with episodes of generalized tonic–clonic seizures once every 4–6 months since 4 years of age. There was no preceding aura or any localizing features. No focal neurological deficit was noted. The patient’s examination revealed a full scale intelligence quotient (IQ) of 72, suggesting marginal learning disability. The Mini-Mental Scale Examination (MSME) revealed a score of 19, indicating mild cognitive impairment. There was no significant history that could be indicative of hypoxic ischemic antenatal insult or genetic predisposition for the symptoms. No significant past history of head trauma, febrile seizures, or meningoencephalitis was present. However, the patient had poor academic performance. No dysmorphic features could be identified. No cognitive deficits/signs to suggest cerebellar pathology were seen on neurological examination. Electroencephalography (EEG) showed generalized spike and wave discharges. Multiplanar and multisequence non-contrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was performed using a 1.5-T MRI scanner (GE SIGNA). Reduced volume of the right cerebellar hemisphere was seen with disorganized architecture, fissural misorientation with individual folia running vertically rather than horizontally, abnormal folial pattern, and arborization of white matter. Signal intensity of cerebellar cortex as well as white matter was normal. No heterotopic nodules were seen. The right side of the vermis also showed relative hypoplasia with an abnormal folial pattern. The left cerebellar hemisphere was normal in morphology and signal intensity. A small extra-axial CSF collection was seen posterior to the dysplastic right cerebellar hemisphere, which was communicating with the fourth ventricle. Ipsilateral posterior fossa was relatively smaller (Figs. 1, 2, 3). No other structural or signal abnormality was noted in the rest of the brain. The patient was put on symptomatic treatment after neurosurgical review ruled out possibility of any favourable surgical intervention.

Conclusions

Notable isolated unilateral cerebellar dysplasia is a rare entity requiring symptomatic treatment and anomalous developmental process being the likely aetiology. As there are just a few reported cases, this case shall contribute to increase in awareness for this entity so that it can be diagnosed without delay and managed appropriately.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to [patient confidentiality], but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Soto-Ares G, Delmaire C, Deries B, Vallee L, Pruvo JP. Cerebellar cortical dysplasia: MR findings in a complex entity. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21(8):1511–9.

Yachnis AT, Rorke LB, Trojanowski JQ. Cerebellar dysplasias in humans: development and possible relationship to glial and primitive neuroectodermal tumors of the cerebellar vermis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1994;53(1):61–71.

Baek H. Disorganized foliation of unilateral cerebellar hemisphere as cerebellar cortical dysplasia in patients with recurrent seizures: a case report. J Korean Soc Radiol. 2013;1(69):177.

Barkovich AJ. Neuroimaging manifestations and classification of congenital muscular dystrophies. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19(8):1389–96.

Demaerel P, Lagae L, Casaer P, Baert AL. MR of cerebellar cortical dysplasia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19(5):984–6.

Patel S, Barkovich AJ. Analysis and classification of cerebellar malformations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23(7):1074–87.

Bosemani T, Orman G, Boltshauser E, Tekes A, Huisman TA, Poretti A. Congenital abnormalities of the posterior fossa. Radiographics. 2015;35(1):200–20.

Chatur C, Balani A, Vadapalli R, Murthy MG. Isolated unilateral cerebellar hemispheric dysplasia: a rare entity. Can J Neurol Sci. 2019;46(6):760–1.

Demaerel P. Abnormalities of cerebellar foliation and fissuration: classification, neurogenetics and clinicoradiological correlations. Neuroradiology. 2002;44(8):639–46.

Barth PG. Pontocerebellar hypoplasias. An overview of a group of inherited neurodegenerative disorders with fetal onset. Brain Dev. 1993;15(6):411–22.

Larroche JC. Morphological criteria of central nervous system development in the human foetus. J Neuroradiol. 1981;8(2):93–108.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RB did literature search, manuscript preparation, data acquisition and analysis. AA conceptualized, designed the case report, performed manuscript editing and review. Both the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent for the patient information and images to be published was obtained from the patient. Due approval was obtained from Ethics committee of NC Medical College and Hospital, Israna, Panipat, Haryana).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for the patient information and images to be published was obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

There were no financial or non-financial competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Babal, R., Aggarwal, A. A rare case report of non-syndromic unilateral cerebellar dysplasia and hypoplasia: a diagnostic enigma. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatry Neurosurg 59, 123 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-023-00723-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-023-00723-6