Abstract

Background

Three-dimensional (3D) reconstructed computed tomography (CT) is crucial for the reliable and accurate evaluation of tunnel enlargement after anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction. The purposes of this study were to evaluate the tibial tunnel enlargement at the tunnel aperture and inside the tunnel and to clarify the morphological change at the tunnel footprint 1 year after the anatomic triple-bundle (ATB) ACL reconstruction using 3D CT models.

Methods

Eighteen patients with unilateral ACL rupture were evaluated. The ATB ACL reconstruction with a semitendinosus tendon autograft was performed. 3D computer models of the tibia and the three tibial tunnels were reconstructed from CT data obtained 3 weeks and 1 year after surgery. The cross-sectional areas (CSAs) of the two anterior and the one posterior tunnels were measured at the tunnel aperture and 5 and 10 mm distal from the aperture and compared between the two periods. The locations of the center and the anterior, posterior, medial, and lateral edges of each tunnel footprint were also measured and compared between the two periods.

Results

The CSA of the posterior tunnel was significantly enlarged at the aperture by 40.4%, whereas that of the anterior tunnels did not change significantly, although the enlargement rate was 6.1%. On the other hand, the CSA was significantly reduced at 10 mm distal from the aperture in the anterior tunnels. The enlargement rate in the posterior tunnel was significantly greater than that in the anterior tunnels at the aperture. The center of the posterior tunnel footprint significantly shifted postero-laterally. The anterior and posterior edges of the posterior tunnel footprint demonstrated a significant posterior shift, while the lateral edge significantly shifted laterally. There was no significant shift of the center or all the edges of the anterior tunnels footprint.

Conclusions

The posterior tibial tunnel was significantly enlarged at the aperture by 40% with the morphological change in the postero-lateral direction reflected by the ACL fiber orientation 1 year after the ATB ACL reconstruction. The proper tibial tunnel location in the ACL reconstruction should be determined considering the tunnel enlargement in postero-lateral direction after surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Tunnel enlargement after anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction has been well documented (Buelow et al., 2002; Clatworthy et al., 1999; L’Insalata et al., 1997; Webster et al., 2001; Wilson et al., 2004). Multiple factors are implicated in the etiology of the enlargement and divided into two categories: mechanical and biological factors (Wilson et al., 2004). The “windshield wiper effect” (L’Insalata et al., 1997) and the “bungee cord effect” (Höher et al., 1998) as the graft motion at the graft–tunnel interface are mechanical factors. Biological factors include non-specific inflammatory response by synovial fluid propagation into the tunnel (Berg et al., 2001; Zysk et al., 2004) and allograft-provoked immune response (Robbrecht et al., 2014). Mechanical factors play a key role in tunnel enlargement (Ge et al., 2015; Iorio et al., 2008; Jagodzinski et al., 2005). Thus, excessive tension of the graft (Jagodzinski et al., 2005; Segawa et al., 2003), non-anatomical tunnel placement (Segawa et al., 2001; Xu et al., 2011), and aggressive rehabilitation (Hantes et al., 2004; Vadalà et al., 2007) are associated with the phenomenon. The presence of tunnel enlargement may lead to increased knee laxity or worse clinical outcome in the longer follow-up although it is insignificant in the short term (Buelow et al., 2002; Clatworthy et al., 1999; Fules et al., 2003; L’Insalata et al., 1997; Webster et al., 2001). Furthermore, tunnel enlargement often complicates revision ACL surgery as for proper tunnel placement (Wilson et al., 2004) and requirement of a two-staged procedure with bone grafting (Thomas et al., 2005).

The ACL is generally divided into two main bundles: anteromedial (AM) and posterolateral (PL) bundles. The double-bundle ACL reconstruction with hamstring tendon grafts has been widely performed with good clinical outcomes including knee stability (Aglietti et al., 2010; Amano et al., 2015; van Eck et al., 2012). On the other hand, Norwood et al. (1979) reported the highly-detailed anatomy of the ACL that was composed of three bundles. Then, Shino et al. (2005) developed the anatomic triple-bundle (ATB) ACL reconstruction with hamstring tendon grafts. This procedure included two femoral and three tibial tunnels in the ACL footprint in order to mimic the native ACL fiber arrangement. Thus, the stress applied to the tibial tunnel wall may be diminished because three tunnels have a larger contact area to the graft than two tunnels. Indeed, tunnel enlargement after the double-bundle ACL reconstruction was proved to be less than that after the single-bundle procedure (Aga et al., 2017; Järvelä et al., 2008; Kawaguchi et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2015). Moreover, in addition to creation of the multiple tunnels, a lower initial tension was utilized for graft fixation not to apply excessive load to the graft in the procedure (Mae et al., 2010, 2013). Therefore, it is expected that tibial tunnel enlargement may be reduced after the ATB ACL reconstruction.

Computed tomography (CT) is shown to be more reliable imaging modality for the evaluation of tunnel enlargement than magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) because the sclerotic tunnel margin is clearly visualized (Marchant et al., 2010). In addition, multi-planar analysis using three-dimensional (3D) reconstructed CT images enables more accurate evaluation because the tunnel enlargement occurs in multiple directions (Basson et al., 2016; Robbrecht et al., 2014). We previously evaluated the femoral tunnel enlargement at the tunnel aperture and inside the tunnel and clarified the morphological change at the tunnel footprint after the ATB ACL reconstruction using 3D CT models (Tachibana et al., 2015). However, to the best of our knowledge, there are only few reports of tibial tunnel enlargement after ACL reconstruction evaluated by 3D CT (Aga et al., 2017; Araki et al., 2014). Therefore, the objectives of this study were 1) to evaluate the tibial tunnel enlargement not only at the tunnel aperture but also inside the tunnel and 2) to clarify the morphological change at the tunnel footprint 1 year after the ATB ACL reconstruction using 3D CT models. Our hypotheses were 1) that the tibial tunnel enlargement 1 year after the ATB ACL reconstruction would be smaller than that in the previous reports and 2) that the morphology at the tunnel footprint would change in the postero-lateral direction reflected by the ACL fiber orientation from the medial wall of the lateral femoral condyle to the anteromedial aspect of the tibial plateau (Otsubo et al., 2012).

Methods

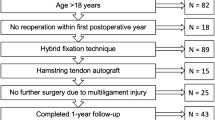

From June 2009 to February 2016, 22 patients with unilateral ACL injury were enrolled in this study. Seven patients were newly added to the cohort in our previous report concerning the femoral tunnel enlargement (Tachibana et al., 2015). This study received the approval of the institutional review board of Osaka University Hospital for human subject research (ID: 09157–2), and the informed consent to participate in this study was obtained from all the patients. They consisted of 8 males and 14 females with a mean age of 25.6 years (range, 14–48 years) at the time of surgery. They all consented to take CT examination at 3 weeks and 1 year after surgery. The cases with revision surgery, multi-ligamentous injury, and apparent osteoarthritic change on radiographic examination (greater than grade II according to the Kellgren and Lawrence classification) were excluded. Previous Tegner activity level scale ranged from 3 to 9, with a mean scale of 7.2. The cause of the ACL injury was trauma related to sporting activity in all but one patient with the injury at work. Surgery was performed in all cases by two surgeons with over 20-year experience (T.M. and K.N.). All meniscal tears including five lateral, three medial and three bilateral tears, were treated by meniscal repairs, whereas no meniscectomies were performed. There were no patients with severe articular cartilage damage greater than grade II according to the Outerbridge classification system.

Surgical technique

The ATB ACL reconstruction was performed as previously described (Shino et al. 2015, 2005). The semitendinosus tendon was harvested and transected into two double-looped grafts: the medial and lateral portions of the AM (AMM/AML) graft and the PL graft. The loop end of each graft was used for the femoral side. The free ends of the PL graft were unified, while those of the AMM/AML graft were left bifurcated as the AMM and AML bundles. The diameter of each graft was measured by graft sizing tubes (Smith & Nephew Endoscopy, Andover, MA, USA).

The torn ACL was removed to clearly visualize the ACL footprint. Two 2.4-mm guide pins were inserted from the lateral femoral cortex to the femoral ACL footprint behind the resident’s ridge and just anterior to the cartilage margin (Iwahashi et al., 2010) with an anterolateral entry femoral aimer (Smith & Nephew Endoscopy). Two 5.0- to 6.0-mm femoral tunnels matched with the graft diameters were created for the AMM/AML and PL grafts by over-drilling via the guide pins. For the tibia, three 2.4-mm guide pins were parallelly inserted from the medial tibial cortex to the anteromedial portion of the tibial ACL footprint (Otsubo et al., 2012) with a tibial tip aimer (Smith & Nephew Endoscopy). The guide pins were over-drilled to create two anteriorly-located tunnels (4.5- to 5.0-mm) for the two portions of the AMM/AML graft and one posteriorly-located tunnel (5.0- to 6.0-mm) for the PL graft, matching the graft diameters. Two Endobutton-CLs (Smith & Nephew Endoscopy) with appropriate loop lengths were connected to each loop end of the two grafts. The unified tibial end of the PL graft was sutured with two No. 2 polyethylene sutures using a Krackow stitch. Each tibial end of the bifurcated AMM/AML graft was also sutured with a No. 2 polyethylene suture by a Krackow stitch, respectively.

The femoral loop end of the PL graft with an Endobutton on the top was introduced through the posterior tibial tunnel into the lower femoral tunnel and fixed by turning the Endobutton. The sutures from the tibial end of the PL graft were tied to a Double-Spike Plate (DSP; MEIRA, Nagoya, Japan). The femoral loop end of the AMM/AML graft was introduced through the far AM portal into the upper femoral tunnel and fixed in the same manner. The two sutured tibial ends of the AMM/AML graft were introduced from the intra-joint into the two anterior tibial tunnels, respectively. It was secured that more than 13 mm of the tibial ends of both grafts were inside the tibial tunnels. The sutures from the tibial ends of the AMM/AML graft were tied together to another DSP. Two DSPs were connected to the tensioners installed in a tensioning boot and manually pulled repetitively to remove the creep of the grafts. Finally, the fixation of the grafts was achieved by anchoring the DSPs to the tibia with cancellous screws, under a total initial tension of 20 N (10 N for the AMM/AML graft and 10 N for the PL graft) at 20 ° of knee flexion.

Rehabilitation programs

After immobilization with a brace for 2 weeks, range of motion exercises and partial weight-bearing were started. Full weight-bearing and jogging were permitted 4 weeks and 3 months after surgery, respectively. Return to previous sporting activity was allowed 7–9 months after surgery, depending on the recovery of the extensor and the flexor power of the knee (more than 80% of the contralateral healthy side).

Clinical examinations

Range of motion, knee swelling, patellar ballottement, and knee instability involving Lachman test and pivot shift test were examined 1 year after surgery. Instrumented anterior knee laxity was measured with a KT-2000 Knee Ligament Arthrometer (MEDmetric, San Diego, CA, USA), and the side-to-side difference at a manual maximum anterior tibial load was adopted as a parameter. In addition, activity level was evaluated by Tegner activity level scale.

Measurement of cross-sectional area and enlargement rate

CT scans were taken 3 weeks and 1 year after surgery with a CT scanner (Discovery CT 750HD; General Electric, Boston, MA, USA). The volume area included 10 cm above and below the knee joint line. The collimation was 16 × 0.625 mm, the tube parameters were 200 mA and 120 kV, the acquisition matrix was 512 × 512, the field of view was 180 mm, and the slice thickness was 0.625 mm. The Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) data obtained by the CT scans were transferred to a computer workstation (Dell Precision T1700; Dell, Round Rock, TX, USA). 3D computer models of the tibia and the three tibial tunnels at 3 weeks and 1 year after surgery were reconstructed from these data using a Visualization Tool Kit (Kitware Inc., Clifton Park, NY, USA)-based original program (Oka et al., 2009). The 3D model of the tibia at 1 year after surgery was superimposed to that at 3 weeks using a surface registration method, and the translation/rotation matrix was obtained. This method was performed by independently implementing the iterative closest point algorithm (Audette et al., 2000) with the least-squares procedure to match the two models. Then, the 3D models of the tibial tunnels at 1 year after surgery was superimposed to those at 3 weeks by applying the obtained translation/rotation matrix (Fig. 1a).

a Reconstruction and superimposition of the three-dimensional (3D) models of the tibia and the three tibial tunnels at 3 weeks and 1 year after surgery. The red and the green 3D models indicate the two anterior tunnels at 3 weeks and 1 year after surgery, respectively. The blue and the yellow 3D models indicate the posterior tunnel at 3 weeks and 1 year after surgery, respectively. b Measurement of the cross-sectional areas (CSAs) of the tibial tunnels at 3 weeks and 1 year after surgery. The measurement was performed by cutting the 3D models of the two anterior tunnels (left) and the posterior tunnel (right), along the planes perpendicular to the tunnel axes (black arrow head), at the aperture and 5 and 10 mm distal from the aperture. The bottom right cube has a length of 20 mm on each side. M: medial, L: lateral, A: anterior, P: posterior

The tunnel axes of the two anterior tunnels for the AMM/AML graft and the one posterior tunnel for the PL graft at 3 weeks were calculated, respectively. Since the 3D models of the tibial tunnels at 3 weeks after surgery were nearly cylindrical shape, the tunnel axis was defined as the longitudinal axis of the principal axes of inertia (eigenvectors of the tensor of inertia). The centroids of the numerous triangular facets forming the surface of the 3D model were used for calculating the moment arm around an axis, and the principal axes of inertia were automatically determined. Then, the cross-sectional area (CSA) of the tunnel was calculated by cutting the 3D construct along the planes perpendicular to the tunnel axis. The CSAs of the two anterior tunnels and the one posterior tunnel were measured at 3 weeks and 1 year, respectively. The two anterior tunnels were evaluated together in the CSA measurement because the two anterior tunnels were communicated in three cases with a small ACL footprint. When the two anterior tunnels were not communicated, the CSA of the two anterior tunnels were calculated as the sum of the separately measured CSAs of each tunnel. “The aperture” was defined as the most proximal plane completely surrounded by bony area, and the CSA was measured at the aperture and 5 and 10 mm distal from the aperture (Fig. 1b). The tunnel length (distance from the aperture to the most distal plane completely surrounded by bony area) at 3 weeks after surgery was 24.8 ± 3.1 mm in the anterior tunnels and 34.2 ± 4.0 mm in the posterior tunnel (Fig. 2). The CSAs were compared between the two periods including that calculated from the drill size intraoperatively. The tunnel enlargement rate from 3 weeks to 1 year after surgery was also calculated and compared between the anterior and the posterior tunnels.

Difference in the tunnel length between the anterior tunnels (left) and the posterior tunnel (right). The tunnel length was defined as the distance from the aperture plane to the most distal plane completely surrounded by bony area of the three-dimensional (3D) models of the tunnels. The red and the blue 3D models indicate the anterior and the posterior tunnels at 3 weeks after surgery. The bottom right cube has a length of 20 mm on each side. M: medial, L: lateral, A: anterior, P: posterior

Location of the center and edges of the tunnel footprint

According to the previously reported coordinate system for the tibial plateau surface (Tsukada et al., 2008), the locations of the center and the edges of the tunnel footprint were measured. Upper viewed images of the tibial 3D models at the two periods on the plane parallel to the tibial plateau were obtained. Using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA), the outlines of the tunnel footprints were determined by connecting the manually plotted multiple points (over 30 plots), and the centers of the two anterior and the one posterior tunnels footprints were automatically calculated. When the two anterior tunnels footprints were not communicated, the midpoint of the centers of each anterior tunnel footprint was employed as the center of the two anterior tunnels footprints. The transverse tangent line between the most posterior margins of the medial and the lateral tibial condyles was defined as the posterior border. Next, the longitudinal line perpendicular to the transverse line and tangent to the medial and the lateral margins of the tibial plateau was defined as the medial and the lateral border, respectively. Finally, the transverse line parallel to the posterior border and tangent to the anterior margin of the tibial plateau was defined as the anterior border.

The location of the center of each tunnel footprint was measured as a percentage of the anterior–posterior and the medial–lateral distances on the tibial plateau from the anterior and the medial tibial borders (Fig. 3a). The locations of the anterior and posterior edges of each tunnel footprint were also measured as percentages of the anterior–posterior distance on the tibial plateau, while those of the medial and lateral edges were measured as percentages of the medial–lateral distance on the plateau (Fig. 3b). By comparing the locations of the center and the edges between the two periods, the translation of the tunnel footprint was evaluated.

a Measurement of the center location of the tibial tunnel footprint. The locations of the centers of the anterior and the posterior tunnels footprints were measured as percentages of the anterior–posterior and the medial–lateral distances on the tibial plateau from the anterior and the medial borders, respectively. b Measurement of the location of the anterior, posterior, medial, and lateral edges of the anterior tunnels footprints. The locations of the anterior and posterior edges of the footprint were measured as percentages of the anterior–posterior distance on the tibial plateau, while those of the medial and lateral edges were measured as percentages of the medial–lateral distance on the plateau, respectively. M: medial, L: lateral, A: anterior, P: posterior

The intra- and inter-observer intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) was 0.98–0.99 (standard deviation, 0.1–0.4) for the measurement of the CSA and 0.94–0.98 (standard deviation, 0.2–0.7) for the measurement of the location of the edge of the tunnel footprint (Tachibana et al., 2015).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with JMP software (JMP Pro version 13.1.0; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Power analysis (power 0.8; α 0.05; detectable difference 8.0; standard deviation 5.1) indicated a sample size requirement of 15 subjects for valid comparisons. The null hypothesis of normal distribution of the data obtained in this study was tested and denied by the Shapiro-Wilk W test. Therefore, when the CSA of the tibial tunnel was assessed, the Friedman test for one-way repeated measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) by ranks and the Steel-Dwass test for post-hoc multiple comparison were used to compare the change of non-parametric variables among three different time points. When the enlargement rate of the tibial tunnel was assessed, the Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used to compare non-parametric variables between two groups. When the locations of the center and the edges of the tunnel footprint were assessed, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the change of non-parametric variables between two different time point. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical examinations

There was no patient with loss of knee flexion/extension exceeding 5 °, knee swelling, patellar ballottement, or positive Lachman or pivot shift test 1 year after surgery. The mean side-to-side difference of the anterior knee laxity measured by a KT-2000 arthrometer was 0.4 ± 1.2 mm and the mean Tegner activity level scale was 6.8 (range, 3–9) at the final follow-up. Seventeen of the 22 patients returned to their former activity level, while 5 patients reduced their activity level because of graduation from school or fear of re-injury.

CSA and enlargement rate

Four cases with the anterior tunnels merging with the posterior tunnel at 1 year CT follow-up were excluded from the evaluation due to the impossibility to discriminate the border between the anterior and the posterior tunnels. It was because we intended to compare the results of this study with those in previous reports after double-bundle ACL reconstruction which were usually reported separately in the anterior and the posterior tunnels (Achtnich et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2012; Siebold & Cafaltzis, 2010). Therefore, the data from 18 patients was finally evaluated.

As the Friedman test detected significant differences among the CSAs at three different time points at the tunnel aperture in the posterior tunnel and 10 mm distal from the aperture in the anterior tunnels (P < 0.05), the Steel-Dwass test for post-hoc multiple comparison was conducted. At the aperture in the posterior tunnel, the CSA at 1 year after surgery was significantly larger than those at 3 weeks and calculated from the intraoperative drill size. At 10 mm from the aperture in the anterior tunnels, the CSA at 1 year after surgery was significantly smaller than those at the other two time points. There was no significant difference between the CSA calculated from the intraoperative drill size and that at 3 weeks after surgery (Table 1). The tunnel enlargement rate was 6.1% in the anterior and 40.4% in the posterior tunnels and the enlargement rate in the posterior tunnel was significantly greater than that in the anterior tunnels at the aperture site (Fig. 4).

Location of the center and edges of the tunnel footprint

There was no significant shift of the center and all the edges of the anterior tunnels footprint from 3 weeks to 1 year after surgery. The center of the posterior tunnel footprint significantly shifted postero-laterally. The anterior and posterior edges of the posterior tunnel footprint demonstrated a significant posterior shift, while the lateral edge of the posterior tunnel footprint significantly shifted laterally (Table 2).

Discussion

The principal findings of this study were 1) the tibial tunnel enlargement rate 1 year after the ATB ACL reconstruction was 6.1% in the anterior and 40.4% in the posterior tunnels at the aperture site and the rate was seemed to be smaller than that in the previous reports and 2) the center and edges of the posterior tunnel footprint shifted postero-laterally reflected by the ACL fiber orientation.

Recently, tibial tunnel enlargement rate after double-bundle ACL reconstruction have been reported to be 21–41% for the anterior and 38–45% for the posterior tunnel on MRI (Achtnich et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2012; Siebold & Cafaltzis, 2010). However, these evaluations have been performed by measuring the tunnel diameter on a two-dimensional (2D) plane and only at one area (most enlarged area or 1- or 2-cm distal from the joint line). 3D CT analysis is a more reliable and accurate evaluation method of tunnel enlargement after ACL reconstruction (Basson et al., 2016; Robbrecht et al., 2014). Therefore, we evaluated the tibial tunnel enlargement after the ATB ACL reconstruction using 3D CT models. The enlargement rate at the aperture was 6.1% in the anterior and 40.4% in the posterior tunnels 1 year after the ATB ACL reconstruction. The enlargement rate in the present study was considered to be less than those in previous reports (Achtnich et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2012; Siebold & Cafaltzis, 2010), because the estimated enlargement rate “in diameter” was 3.0% in the anterior and 18.5% in the posterior tunnels if the tunnel enlargement occurred in posterior and lateral directions equally. The smaller tunnel enlargement rate might be affected by performing the anatomic ACL reconstruction with three tibial tunnels and a lower tension for the graft fixation and conducting relatively gentle rehabilitation programs.

On the other hand, the enlargement rate decreased gradually from the aperture toward the inside of the tunnel, and the tunnel shape was conical as with previous reports of tunnel enlargement after ACL reconstruction with hamstring tendon grafts (Araki et al., 2014; Basson et al., 2016; Fules et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2012). The hamstring tendon graft is typically fixed extra-cortically using suspensory fixation devices, and the graft moves within the tunnel around the extra-cortical fixation point as a fulcrum. Thus, the force between the graft and the tunnel wall should be considered as a rotational moment and increase gradually from the extra-cortical fixation point to the tunnel aperture. In animal studies, the graft–tunnel motion increased gradually from the tunnel exit to the tunnel aperture, and the graft–tunnel healing inversely correlated with this motion (Bedi et al., 2009; Rodeo et al. 2006). (Giron et al. 2005) reported that the tunnel enlargement rate was correlated with the distance from the extra-cortical graft fixation point. We thought that this was the reason why the tunnel after ACL reconstruction with hamstring tendon grafts formed into the conical shape.

Besides, the enlargement rate in the posterior tunnel was significantly greater than that in the anterior tunnels at the aperture site. We considered the reason for the difference as follows. First, two anteriorly-located 4.5- to 5.0-mm and one posteriorly-located 5.0- to 6.0-mm tibial tunnels were created in the ATB ACL reconstruction, while the same initial tension was applied to each graft. Thus, the applied stress to the tunnel wall might be smaller in the anterior tunnels than that in the posterior tunnel, because the anterior tunnels had a larger contact area to the graft than the posterior tunnel. Second, it has been reported that the in situ force of the ACL increased and the force of the PL bundle was higher than those of the AMM or AML bundle at hyperextension during passive flexion-extension (Fujie et al., 2011). Therefore, the force applied to the posterior tunnel wall might be greater than that of the anterior tunnels. Finally, the distance between the tunnel aperture and the extra-cortical fixation point was greater in the posterior tunnel compared to the anterior tunnels (Fig. 2). The longer distance from the fixation point in the posterior tunnel might affect the enlargement rate at the aperture as suggested in previous reports (Buelow et al., 2002; Fauno & Kaalund, 2005; Giron et al., 2005).

In the present study, the center and edges of the tunnel footprint shifted postero-laterally over time after surgery in the posterior tunnel. As the ACL fiber runs postero-laterally from the medial wall of the lateral femoral condyle to the anteromedial aspect of the tibial plateau 31, the tibial tunnel enlargement also occurred in postero-lateral direction reflected by the fiber arrangement of the ACL. In addition, the anterior edge of the posterior tunnel footprint shifted posteriorly. This indicated that newly formed bones infiltrated into the anterior area where the stress was not applied as suggested in previous reports (Araki et al., 2014; Tachibana et al., 2015; Yamakado et al., 2002). Thus, the tibial tunnel was enlarged in the postero-lateral direction reflected by the ACL fiber orientation at the aperture site, especially in the posterior tunnel, even though we performed anatomic ACL reconstruction with a lower tension for the graft fixation and relatively gentle postoperative rehabilitation. The clinical relevance of this study is that tibial tunnel enlargement after ACL reconstruction may not be avoided to some extent as far as tendon graft is used although it doesn’t lead to increased knee laxity in the short term as shown in this study. However, the presence of tunnel enlargement may lead to increased knee laxity or worse clinical outcome in the longer follow-up. The proper tibial tunnel location in the ACL reconstruction should be determined considering the tunnel enlargement in postero-lateral direction after surgery, and creation of the tibial tunnel within the antero-medial area in the ACL footprint may be preferable.

There were some limitations in this study. First, we followed the patients for only 1 year. The tunnel enlargement occurs during the first 3–6 months after ACL reconstruction and don’t proceed thereafter (Buelow et al., 2002; Sun et al., 2015; Webster et al., 2001). However, we are continuing to follow up patients over 1 year after surgery. Second, the evaluation was performed on only one surgical procedure, not compared to single- or double-bundle ACL reconstruction with hamstring tendon grafts or ACL reconstruction using a bone-patellar tendon-bone graft. The tunnel enlargement after ACL reconstruction with hamstring tendon grafts have been reported to be greater than that using a bone-patellar tendon-bone graft (Clatworthy et al., 1999; L’Insalata et al., 1997; Webster et al., 2001). Therefore, the change of the CSA of the tibial tunnel and morphology at the tunnel footprint after ACL reconstruction with a bone-patellar tendon-bone graft may be different from that in the present study.

Conclusions

The posterior tibial tunnel was significantly enlarged at the aperture by 40% with the morphological change in the postero-lateral direction reflected by the ACL fiber orientation 1 year after the ATB ACL reconstruction. The proper tibial tunnel location in the ACL reconstruction should be determined considering the tunnel enlargement in postero-lateral direction after surgery.

Abbreviations

- 3D:

-

Three-dimensional

- ACL:

-

Anterior cruciate ligament

- AM:

-

Anteromedial

- AML:

-

Lateral portion of the anteromedial

- AMM:

-

Medial portion of the anteromedial

- ATB:

-

Anatomic triple-bundle

- CSA:

-

Cross-sectional area

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PL:

-

Posterolateral

- RM-ANOVA:

-

Repeated measures analysis of variance

References

Achtnich A, Stiepani H, Forkel P, Metzlaff S, Hänninen EL, Petersen W (2013) Tunnel widening after anatomic double-bundle and mid-position single-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 29(9):1514–1524

Aga C, Wilson KJ, Johansen S, Dornan G, La Prade RF, Engebretsen L (2017) Tunnel widening in single- versus double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstructed knees. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 25(4):1316–1327

Aglietti P, Giron F, Lasco M, Cuomo P, Ciardullo A, Mondanelli N (2010) Comparison between single-and double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective, randomized, single-blinded clinical trial. Am J Sports Med 38(1):25–34

Amano H, Toritsuka Y, Uchida R, Mae T, Ohzono K, Shino K (2015) Outcome of anatomical double-bundle ACL reconstruction using hamstring tendons via an outside-in approach. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 23(4):1222–1230

Araki D, Kuroda R, Matsumoto T, Nagamune K, Matsushita T, Hoshino Y, Oka S, Nishizawa Y, Kurosaka M (2014) Three-dimensional analysis of bone tunnel changes after anatomic double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using multidetector-row computed tomography. Am J Sports Med 42(9):2234–2241

Audette MA, Ferrie FP, Peters TM (2000) An algorithmic overview of surface registration techniques for medical imaging. Med Image Anal 4(3):201–217

Basson B, Philippot R, Neri T, Meucci JF, Boyer B, Farizon F (2016) The effect of femoral tunnel widening on one-year clinical outcome after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using ZipLoop® technology for fixation in the cortical bone of the femur. Knee 23(2):233–236

Bedi A, Kawamura S, Ying L, Rodeo SA (2009) Differences in tendon graft healing between the intra-articular and extra-articular ends of a bone tunnel. HSS J 5(1):51–57

Berg EE, Pollard ME, Kang Q (2001) Interarticular bone tunnel healing. Arthroscopy 17(2):189–195

Buelow JU, Siebold R, Ellermann A (2002) A prospective evaluation of tunnel enlargement in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with hamstrings: extracortical versus anatomical fixation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 10(2):80–85

Clatworthy MG, Annear P, Bulow JU, Bartlett RJ (1999) Tunnel widening in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective evaluation of hamstring and patella tendon grafts. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 7(3):138–145

Fauno P, Kaalund S (2005) Tunnel widening after hamstring anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction is influenced by the type of graft fixation used: a prospective randomized study. Arthroscopy 21(11):1337–1341

Fujie H, Otsubo H, Fukano S, Suzuki T, Suzuki D, Mae T, Shino K (2011) Mechanical functions of the three bundles consisting of the human anterior cruciate ligament. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 19(Suppl 1):S47–S53

Fules PJ, Madhav RT, Goddard RK, Newman-Sanders A, Mowbray MA (2003) Evaluation of tibial bone tunnel enlargement using MRI scan cross-sectional area measurement after autologous hamstring tendon ACL replacement. Knee 10(1):87–91

Ge Y, Li H, Tao H, Hua Y, Chen J, Chen S (2015) Comparison of tendon-bone healing between autografts and allografts after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using magnetic resonance imaging. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 23(4):954–960

Giron F, Aglietti P, Cuomo P, Mondanelli N, Ciardullo A (2005) Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with double-looped semitendinosus and gracilis tendon graft directly fixed to cortical bone: 5-year results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 13(2):81–91

Hantes ME, Mastrokalos DS, Yu J, Paessler HH (2004) The effect of early motion on tibial tunnel widening after anterior cruciate ligament replacement using hamstring tendon grafts. Arthroscopy 20(6):572–580

Höher J, Möller HD, Fu FH (1998) Bone tunnel enlargement after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: fact or fiction? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 6(4):231–240

Iorio R, Vadalà A, Di Vavo I, De Carli A, Conteduca F, Argento G, Ferretti A (2008) Tunnel enlargement after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in patients with post-operative septic arthritis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 16(10):921–927

Iwahashi T, Shino K, Nakata K, Otsubo H, Suzuki T, Amano H, Nakamura N (2010) Direct anterior cruciate ligament insertion to the femur assessed by histology and 3-dimensional volume-rendered computed tomography. Arthroscopy 26(9 Suppl):S13–174

Jagodzinski M, Foerstemann T, Mall G, Krettek C, Bosch U, Paessler HH (2005) Analysis of forces of ACL reconstructions at the tunnel entrance: is tunnel enlargement a biomechanical problem? J Biomech 38(1):23–31

Järvelä T, Moisala AS, Paakkala T, Paakkala A (2008) Tunnel enlargement after double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective, randomized study. Arthroscopy 24(12):1349–1357

Kawaguchi Y, Kondo E, Kitamura N, Kai S, Inoue M, Yasuda K (2011) Comparisons of femoral tunnel enlargement in 169 patients between single-bundle and anatomic double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions with hamstring tendon grafts. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 19(8):1249–1257

L’Insalata JC, Klatt B, Fu FH, Harner CD (1997) Tunnel expansion following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a comparison of hamstring and patellar tendon autografts. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 5(4):234–238

Lee YS, Lee SW, Nam SW, Oh WS, Sim JA, Kwak JH, Lee BK (2012) Analysis of tunnel widening after double-bundle ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 20(11):2243–2250

Mae T, Shino K, Matsumoto N, Natsu-ume T, Yoneda K, Yoshikawa H, Yoneda M (2010) Anatomic double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using hamstring tendons with minimally required initial tension. Arthroscopy 26(10):1289–1295

Mae T, Shino K, Matusmoto N, Yoneda M, Yoshikawa H, Nakata K (2013) Immediate postoperative anterior knee stability: double- versus triple-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions. Arthroscopy 29(2):213–219

Marchant MH Jr, Willimon SC, Vinson E, Pietrobon R, Garrett WE, Higgins LD (2010) Comparison of plain radiography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of bone tunnel widening after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 18(8):1059–1064

Norwood LA, Cross MJ (1979) Anterior cruciate ligament: functional anatomy of its bundles in rotator instabilities. Am J Sports Med 7(1):23–26

Oka K, Murase T, Moritomo H, Goto A, Sugamoto K, Yoshikawa H (2009) Accuracy analysis of three-dimensional bone surface models of the forearm constructed from multidetector computed tomography data. Int J Med Robot 5(4):452–457

Otsubo H, Shino K, Suzuki D, Kamiya T, Suzuki T, Watanabe K, Fujimiya M, Iwahashi T, Yamashita T (2012) The arrangement and the attachment areas of three ACL bundles. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 20(1):127–134

Robbrecht C, Claes S, Cromheecke M, Mahieu P, Kakavelakis K, Victor J, Bellemans J, Verdonk P (2014) Reliability of a semi-automated 3D-CT measuring method for tunnel diameters after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a comparison between soft-tissue single-bundle allograft vs. autograft. Knee 21(5):926–931

Rodeo SA, Kawamura S, Kim HJ, Dynybil C, Ying L (2006) Tendon healing in a bone tunnel differs at the tunnel entrance versus the tunnel exit: an effect of graft-tunnel motion? Am J Sports Med 34(11):1790–1800

Segawa H, Omori G, Tomita S, Koga Y (2001) Bone tunnel enlargement after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using hamstring tendons. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 9(4):206–210

Segawa H, Koga Y, Omori G, Sakamoto M, Hara T (2003) Influence of the femoral tunnel location and angle on the contact pressure in the femoral tunnel in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 31(3):444–448

Shino K, Nakata K, Nakamura N (2005) Anatomic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using two double-looped hamstring tendon grafts via twin femoral and triple tibial tunnels. Oper Tech Orthop 15(2):130–134

Shino K, Mae T, Tachibana Y (2015) Anatomic ACL reconstruction: rectangular tunnel/bone-patellar tendon-bone or triple-bundle/semitendinosus tendon grafting. J Orthop Sci 20(3):457–468

Siebold R, Cafaltzis K (2010) Differentiation between intraoperative and postoperative bone tunnel widening and communication in double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective study. Arthroscopy 26(8):1066–1073

Sun R, Chen BC, Wang F, Wang XF, Chen JQ (2015) Prospective randomized comparison of knee stability and joint degeneration for double- and single-bundle ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 23(4):1171–1178

Tachibana Y, Mae T, Shino K, Kanamoto T, Sugamoto K, Yoshikawa H, Nakata K (2015) Morphological changes in femoral tunnels after anatomic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 23(12):3591–3600

Thomas NP, Kankate R, Wandless F, Pandit H (2005) Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using a 2-taged technique with bone grafting of the tibial tunnel. Am J Sports Med 33(11):1701–1709

Tsukada H, Ishibashi Y, Tsuda E, Fukuda A, Toh S (2008) Anatomical analysis of the anterior cruciate ligament femoral and tibial footprints. J Orthop Sci 13(2):122–129

Vadalà A, Iorio R, De Carli A, Argento G, Di Sanzo V, Conteduca F, Ferretti A (2007) The effect of accelerated, brace free, rehabilitation on bone tunnel enlargement after ACL reconstruction using hamstring tendons: a CT study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 15(4):365–371

van Eck CF, Kopf S, Irrgang JJ, Blankevoort L, Bhandari M, Fu FH, Poolman RW (2012) Single-bundle versus double-bundle reconstruction for anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a meta-analysis—does anatomy matter? Arthroscopy 28(3):405–424

Webster KE, Feller JA, Hameister KA (2001) Bone tunnel enlargement following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a randomized comparison of hamstring and patellar tendon grafts with 2-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 9(2):86–91

Wilson TC, Kantaras A, Atay A, Johnson DL (2004) Tunnel enlargement after anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Am J Sports Med 32(2):543–549

Xu Y, Ao Y, Wang J, Yu J, Cui G (2011) Relation of tunnel enlargement and tunnel placement after single-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 27(7):923–932

Yamakado K, Kitaoka K, Yamada H, Hashiba K, Nakamura R, Tomita K (2002) The influence of mechanical stress on graft healing in a bone tunnel. Arthroscopy 18(1):82–90

Zysk SP, Fraunberger P, Veihelmann A, Dörger M, Kalteis T, Maier M, Pellengahr C, Refior HJ (2004) Tunnel enlargement and changes in synovial fluid cytokine profile following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with patellar tendon and hamstring tendon autografts. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 12(2):98–103

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Tsuyoshi Murase and Mr. Ryoji Nakao for developing the software.

Availability of data and materials

Data will be available upon request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TO analyzed the acquired data, and drafted the manuscript. TM performed the operation, conducted the study and organized all. YT helped to analyze the data. KN performed the operation and supervised the study. KS, KS and HY supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study protocol received the approval of the institutional review board of Osaka University Hospital for human subject research (ID: 09157–2). We obtained the informed consent to participate in this study from all the patients in writing, providing the opportunity to refuse it.

Consent for publication

We offered the publication of the available data regarding this study to all the participants, providing the opportunity to refuse it. Then, we obtained the informed consent from them in writing.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ohori, T., Mae, T., Shino, K. et al. Morphological changes in tibial tunnels after anatomic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with hamstring tendon graft. J EXP ORTOP 4, 30 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40634-017-0104-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40634-017-0104-6