Abstract

Background

A pancreatic duct rupture can lead to various complications such as a fistula, pseudocyst, ascites, or walled-off necrosis. Due to pleural effusion, pancreaticopleural fistula typically causes dyspnea and chest pain. Leaks of enzyme-rich pancreatic fluid forming a pleural effusion can be verified in a thoracocentesis following radiological imaging such as computed tomography or magnetic resonance tomography. While management strategies range from a conservative to endoscopic and surgical approach, we report a case with successful minimally invasive treatment of pancreaticopleural fistula and effusion.

Case presentation

We present a case of a patient with pancreaticopleural fistula and successful minimally invasive surgical treatment. A 62-year old Caucasian man presented with acute chest pain and dyspnea. A computed tomography scan identified a left-sided cystoid formation, extending from the abdominal cavity into the left hemithorax with concomitant pleural effusion. Pleural effusion analysis indicated significantly elevated pancreatic enzymes. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography revealed a rupture of the pancreatic duct and nearby fluid accumulation. Endosonography later confirmed proximity to the tail of the pancreas, suggesting a pancreatic pseudocyst with visible tract into the pancreas. We assumed a pancreatic duct rupture with a fistula from the tail of the pancreas transdiaphragmatically into the left hemithorax with a commencing pleural empyema. A visceral and parietal decortication on the left hemithorax and a laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy was performed. The suspected diagnosis of a fistula arising from the pancreatic duct was confirmed histologically.

Conclusion

Pancreaticopleural fistulas often have a long course and may remain undiagnosed for a long time. At this point diagnostic management and therapy demand a high level of expertise. In instances of unclear symptomatic pleural effusion, considering an abdominal focus is crucial. If endoscopic treatment is not feasible, minimally invasive surgery should strongly be considered, especially when located in the distal pancreas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Pancreatic duct disruption may arise following an acute episode or exacerbation of chronic pancreatitis, surgical procedures, or trauma. Depending on its duration, this disruption can lead to the formation of fistulas, pleural effusion, pseudocysts, and ascites [1, 2]. Typically, middle-aged men are affected, with approximately half of patients having a history of chronic pancreatitis [3]. Up to 40% will develop fluid collections, such as pseudocysts after pancreatitis, which can lead to a pancreaticopleural fistula with recurrent left-sided pleural effusion [4, 5]. In contrast to smaller fluid collections, which are common within the first 4 weeks after pancreatitis onset and often resolve spontaneously [6, 7], there are no specific symptoms directly indicative of a Wirsung duct rupture. Many patients may lack a history of pancreatic disease, typically manifesting with abdominal pain, which may radiate to the back, along with nausea and bloating. However, predominant pulmonary symptoms such as chest pain, dyspnea, and cough can initially obscure an abdominal issue [8]. We underline that surgery remains a valid option if therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography (ERCP) as primary treatment choice is not feasible. This rare case highlights a complication-free minimally invasive thoracic and abdominal surgical approach, as failure in endoscopic management of patients with pancreaticopleural fistula often necessitates more invasive interventions such as open surgery.

Case presentation

A 62-year-old Caucasian man presented in a rural hospital with sudden onset of severe burning pain in the left hemithorax, prompted by his fear of a potential heart attack, given his father’s history. The patient had been suffering from night sweats and weakness over the last weeks. Physical examination showed no tenderness on abdominal pressure, but decreased breath sounds on the left side. Vital parameters were normal, temperature 36.6 °C. Escitalopram (10 mg daily) was the only long-term medication. There was no family history of abdominal illness. Around 5 years ago the patient received a dental crown. He had already contacted his family doctor a year ago because of similar symptoms and a feeling of pressure in the upper abdomen but he did not receive any serious examinations. This time the patient was admitted to hospital.

An immediately performed electrocardiogram showed no abnormalities; heart enzymes were within normal limits. Cardiac origin of pain was thus excluded. Intravenous analgesia relieved the pain significantly. Blood samples yielded slightly elevated inflammatory markers and pancreatic enzymes [leukocytes 13.9 G/L (4.4–11.3G/L), C-reactive protein 2.9 mg/dL (< 0.5 mg/dL), amylase 157 U/L (13–53 U/L), lipase 232 U/L (13–60 U/L)]. Renal and liver parameters were in range. Urinary status was unremarkable. A chest X-ray showed extensive pulmonary infiltrates with accompanying effusion on the left hemithorax. Additionally, an ultrasound of the abdomen and pleura was performed. There was no free fluid in the abdominal cavity but a pleural effusion in the left hemithorax measuring a volume of 400 ml. The provisional diagnosis was pneumonia with accompanying effusion on the left side. Therefore, antibiotic treatment with intravenous penicillin was initiated.

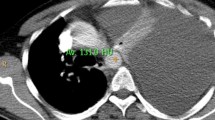

Diagnostic pleural puncture was performed 2 days later, which macroscopically showed a hemorrhagic pleural effusion with high levels of lipase (3000 U/L) and amylase (4800 U/L). On the same day, a computed tomography (CT) of the thorax revealed a 7 × 10 cm (craniocaudal) cystoid fluid collection emanating from the pancreas along the left diaphragmatic crus to the chest with leaking pleural effusion on the left hemithorax of approximately 700 ml and an atelectasis of the lower lobe on the left (Fig. 1).

According to the radiological imaging, the fluid had an intrathoracic origin with a penetration into the abdomen. Thus, malignancy could not be excluded. On the basis of the present findings, antibiotic treatment was escalated with metronidazole 2 days later. After an additional pulmonological assessment at our university clinic, the patient was transferred to our clinic the next day.

We completed the diagnostic workup performing an endosonography (Fig. 2). This showed an encapsulated pleural retention extending from the hiatus retrogastrically toward the pancreatic tail with a visible junction into the tail. Assuming it might be a pancreatic pseudocyst, the fluid collection was punctured in the same session. Amber-colored clear liquid with increased amylase and lipase without bacterial detection was extracted, carcinoembryonic antigen was not elevated.

After the weekend, we further drained the pleural effusion, extracting 700 ml of amber-colored liquid. A second CT scan of the thorax and abdomen showed a regressive effusion after drainage, with a persisting cyst of 6.5 cm craniocaudal in the thorax and 4 cm intraabdominal.

On day 12, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showed an encapsulated fluid collection as in the CT scan. The pancreatic duct could not be clearly defined in the area of the fluid collection but was regular proximal and distal; a clear connection between the duct structure and the cyst could neither be confirmed nor excluded (Fig. 3).

On day 14, an interdisciplinary board of general and visceral surgery, thoracic surgery, and gastroenterology decided upon an imminent surgical approach.

The patient was discharged 18 days after initial presentation with stable low inflammatory parameters and having received prophylactic vaccinations before planned splenectomy, as prior imaging assessed adhesion to splenic vessels. During hospital stay serum lipase and amylase were stable (maximum 196 and 181 U/L).

After recovery from 3 weeks of hospitalization, an elective surgery on day 29 after initial presentation was carried out. A pancreatic specialist and thoracic surgeon performed a left-sided thoracic visceral and parietal decortication via thoracoscopy and laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy combined with laparoscopically assisted splenectomy. Splenectomy was done because of intraoperative unclear borders and adhesion to the vessels as a result of strong inflammation. After dissecting the pancreas retroperitoneally, a tract was detected that reached intrathoracically (Fig. 4). The pancreatic tissue imposed chronically inflamed but the stapled pancreas remained without postoperative leakage. Due to pleural empyema and atelectasis, decortication was necessary. The pancreatic fistula emanating from the pancreatic duct was confirmed histologically. The pancreatic parenchyma showed signs of chronic pancreatitis. The diagnosis of a pancreatic duct rupture with a fistula at the transition from pancreatic body to tail with connection to the thorax on the left and extensive pleural effusion was histologically verified. Somatostatin was initiated for 5 days. Following surgery, the patient experienced an uneventful postoperative course and was discharged on day 10 after surgery; blood sample yielded lipase, amylase, and inflammatory markers in normal range.

Discussion

This case of a 62-year-old Caucasian patient with a massive pleural effusion due to atraumatic pancreaticopleural fistula shows a successful minimally invasive distal pancreatectomy as an appealing approach with low morbidity when the duct rupture is located in the distal part and not accessible for an endoscopic procedure.

A pancreaticopleural fistula is a communication between the pancreatic duct and the pleural cavity. Internal fistulas result from pancreatic disruption, in contrast to sympathetic effusions, which are mostly small and self-limiting [4]. In case of an anterior disruption, a PPF or pancreatic ascites will develop. Compared with a posterior disruption, as in our patient, pancreatic juice will enter a compartment with less resistance as the retroperitoneal space [4, 9]. Fluid erupts through the pleura into the pleural cavity and may form a PPF with leakage and fluid collection. As pancreatic enzymes are not activated due to missing digestion in the thorax, there is no immediate pain [10]. Men between 40 and 50 years are mainly affected, with history of chronic alcoholism in 50%. Trauma is seldom [3, 4]. Malignancy may also cause duct rupture [11]. Our patient had no history of abdominal trauma or pancreatitis, but alcohol consumption of 2–4 beers daily and active nicotine abuse (20 packyears). As a rare entity, pleural effusion occurs in chronic pancreatitis in 0.4–7% and with pancreatic pseudocysts in 6–14%. Due to the anatomy, left-sided pleural effusion is more common (76%), followed by right-sided in 19% and bilateral in 14% [3]. As those effusions can be large and recurrent, while the pancreas produces 1 liter of exocrine secret daily, a diagnostic puncture of the collection is useful [12]. High levels of lipase will then confirm the diagnosis of a PPF, and malign or benign entities can be evaluated [9]. We found increased amylase and lipase in the puncture. High levels of amylase can also be related to pancreatitis, lung carcinoma, or pneumonia as differential diagnosis [4].

As our patient also presented with thoracic pain, clinical features are often misleading as pulmonary symptoms such as chest pain, dyspnea, cough, fever, or weight loss right up to septicemia [3]. Diagnosing PPF takes around 5 weeks [13]. For this reason, the first hint leading to the diagnosis of a PPF with pleural involvement is an abnormal X-ray of the chest typically showing effusion [8]. A CT of the thorax and abdomen is the best option to assess the pancreas and extension of the pseudocyst and pleural effusion, or even detection of the fistula itself is possible in 33% of cases [5, 8]. This should be followed by an endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of the effusion for amylase, lipase, carcinoembryonic antigen, and cytology depending on the availability of a gastroenterologist experienced in endoscopic ultrasound and interventions or just by thoracocentesis [5, 14]. Amylase is not always elevated as it is absorbed through the pleural surface [10]. Serum levels may show high amylase and lipase in case of pancreatitis [9]. In our case a disruption in the tail of the pancreatic duct with a tract into the cyst and concomitant large effusion as demonstrated in the previous endosonography justified surgery in a fit and symptomatic patient. The disruption of the distal pancreatic duct rendered an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography (ERCP) with stent implantation impossible. In addition, total disruption and distal obstruction of the duct is a limitation for stenting [15]. Therefore, we decided to perform pleural drainage to primarily relieve the symptoms followed by an elective laparoscopically assisted distal pancreatectomy. Conservative treatment contains nil per os in the beginning, parenteral alimentation, therapeutic thoracocentesis, and medical treatment with somatostatin (octreotide), suggesting a period of 2–4 weeks [12, 16]. ERCP and stenting should be the primary option for pancreatic rupture, but a complete duct rupture and pancreatitis can reduce therapeutic success [17]. Stenting is therefore only successful when intraductal pressure can be reduced by occluding the disruption or passing the sphincter Oddi [4]. The major concern is stent migration and the duration of stenting to reduce recurrence [18]. Few cases report stent removal after 4–6 weeks [19, 20]. Additionally, pleural effusion needs to be drained. Conservative or endoscopic therapy should be the treatment of choice, especially in patients with comorbidities or necrotising pancreatitis [16]. A review of literature from 2007 to 2017 including 43 cases showed that surgery was necessary after ERCP in 53% of cases; for the other patients, ERCP was successful [21]. Therapeutic ERCP has become more relevant in recent years as it is less invasive, especially because chronic pancreatitis may complicate surgery [22]. Another treatment option is a surgical or endoscopic cystogastrostomy, whereas surgical approach has a higher primary and overall success rate [23]. Initially an endoscopic cystogastrostomy was intended in our case. However, technically it was not possible because most of the cyst formation was located intrathoracically and therefore the cystogastrostomy would have been too close to the hiatus.

If surgical approach is intended, distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy, longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy, and Roux-en-Y reconstruction via laparotomy or the Partington Rochelle procedure (laterolateral pancreaticojejunostomy) are adequate techniques for distal duct rupture [15, 24]. If distal pancreatectomy is unfeasible due to vulnerable tissue (chronic pancreatitis) or duct strictures or if the defect is located more proximal, surgical techniques for pancreatic head resection such as partial pancreaticoduodenectomy, Beger or Frey procedure or Bern modification are possible [24]. Another reason to think about immediate surgical treatment is that conservative treatment has a success rate of 30–60%, a recurrence rate of 15%, and mortality rate of 12%, whereas surgery has a success rate of 90%, a recurrence rate of 18%, and mortality rate of 7.7%. Furthermore, patients with attempted conservative therapy have a longer course of treatment and recovery, with higher morbidity and mortality after secondary surgery [3, 8, 25]. However, surgery is indicated after 3–4 weeks if prior treatment fails [13].

PPF with pleural effusion is rare and it may not be possible to compare different therapeutic strategies. The literature only presents a small number and few up-to-date case series and cannot be compared with treatment of pseudocysts, where a lot of research exists. This disease still needs a tailored approach considering the best individual outcome and health condition. Our patient had no further episode of pain or pancreatitis 1 year after minimally invasive surgery.

Conclusion

A pancreaticopleural fistula with massive pleural effusion is difficult to diagnose when presenting with thoracic symptoms atypical for pancreatic diseases. This case demonstrates a reasonable approach by minimally invasive surgery since endoscopic management as a preferred option is not always feasible.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Farias GFA, Bernardo WM, De Moura DTH, et al. Endoscopic versus surgical treatment for pancreatic pseudocysts: systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2019;98(8):e14255.

Gillams AR, Kurzawinski T, Lees WR. Diagnosis of duct disruption and assessment of pancreatic leak with dynamic secretin-stimulated MR cholangiopancreatography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186(2):499–506.

Machado NO. Pancreaticopleural fistula: revisited. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2012;2012:815476.

Safadi BY, Marks JM. Pancreatic-pleural fistula: the role of ERCP in diagnosis and treatment. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51(2):213–5.

Larsen M, Kozarek R. Management of pancreatic ductal leaks and fistulae. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29(7):1360–70.

Braden B, Dietrich CF. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided endoscopic treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts and walled-off necrosis: new technical developments. World J Gastroenterol WJG. 2014;20(43):16191–6.

Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis 2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62(1):102–11.

King JC, Reber HA, Shiraga S, et al. Pancreatic-pleural fistula is best managed by early operative intervention. Surgery. 2010;147(1):154–9.

Olakowski M, Mieczkowska-Palacz H, Olakowska E, et al. Surgical management of pancreaticopleural fistulas. Acta Chir Belg. 2009;109(6):735–40.

Cameron JL, Kieffer RS, Anderson WJ, et al. Internal pancreatic fistulas: pancreatic ascites and pleural effusions. Ann Surg. 1976;184(5):587–93.

Shohat S, Shulman K, Kessel B, et al. Spontaneous rupture of the main pancreatic duct synchronous with a multi-focal microscopic pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res JCDR. 2016;10(12):5–7.

Balthazar EJ. Complications of acute pancreatitis: clinical and CT evaluation. Radiol Clin North Am. 2002;40(6):1211–27.

Altasan T, Aljehani Y, Almalki A, et al. Pancreaticopleural fistula: an overlooked entity. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2014;22(1):98–101.

Gerosa M, Chiarelli M, Guttadauro A, et al. Wirsung atraumatic rupture in patient with pancreatic pseudocysts: a case presentation. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18(1):52.

Kiewiet JJS, Moret M, Blok WL, et al. Two patients with chronic pancreatitis complicated by a pancreaticopleural fistula. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2009;3(1):36–42.

Khadka M, Bhusal S, Pantha B, et al. Pancreaticopleural fistula causing pleural effusion: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2024;18(1):131.

Das R, Papachristou GI, Slivka A, et al. Endotherapy is effective for pancreatic ductal disruption: a dual center experience. Pancreatol Off J Int Assoc Pancreatol IAP Al. 2016;16(2):278–83.

Varadarajulu S, Wilcox CM. Endoscopic placement of permanent indwelling transmural stents in disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome: does benefit outweigh the risks? Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74(6):1408–12.

Saeed ZA, Ramirez FC, Hepps KS. Endoscopic stent placement for internal and external pancreatic fistulas. Gastroenterology. 1993;105(4):1213–7.

Hastier P, Rouquier P, Buckley M, et al. Endoscopic treatment of wirsungo-cysto-pleural fistula. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10(6):527–9.

Kord Valeshabad A, Acostamadiedo J, Xiao L, et al. Pancreaticopleural fistula: a review of imaging diagnosis and early endoscopic intervention. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2018;19(2018):7589451.

Sasturkar S, Gupta S, Thapar S, et al. Endoscopic management of pleural effusion caused by a pancreatic pleural fistula. J Postgrad Med. 2020;66(4):206–8.

Melman L, Azar R, Beddow K, et al. Primary and overall success rates for clinical outcomes after laparoscopic, endoscopic, and open pancreatic cystgastrostomy for pancreatic pseudocysts. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(2):267–71.

Strobel O, Büchler MW, Werner J. Surgical therapy of chronic pancreatitis: indications, techniques and results. Int J Surg Lond Engl. 2009;7(4):305–12.

Gómez-Cerezo J, Barbado Cano A, Suárez I, et al. Pancreatic ascites: study of therapeutic options by analysis of case reports and case series between the years 1975 and 2000. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(3):568–77.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patient for consent to publish this case report.

Funding

The authors declare that they have no financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SR drafted the manuscript. SR, CA, FK, and AS revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Raab, S., Aigner, C., Kurz, F. et al. Minimally invasive treatment of an internal pancreaticopleural fistula with massive pleural effusion: a case report. J Med Case Reports 18, 430 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-024-04761-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-024-04761-3