Abstract

Background

Focal nodular hyperplasia is a common nonmalignant liver mass. This nonvascular lesion is an uncommon mass in children, especially those with no predisposing factors, namely radiation, chemotherapy, and hematopoietic stem cell therapy. Exophytic growth of the lesion further than the liver margins is not common and can complicate the diagnosis of the lesion. This report observes a focal nodular hyperplasia as a pedunculated lesion in a healthy child.

Case presentation

We describe a 9-year-old healthy Persian child who was born following in vitro fertilization complaining of abdominal pain lasting for months and palpitation. Employing ultrasound and computed tomography, a mass was detected in the right upper quadrant compatible with focal nodular hyperplasia imaging features. The child underwent surgery and the mass was resected.

Conclusion

Diagnosing focal nodular hyperplasia, especially pedunculated form can be challenging, although magnetic resonance imaging with scintigraphy is nearly 100% sensitive and specific. Thus, a biopsy may be needed to rule out malignancies in some cases. Deterministic treatment in patients with suspicious mass, remarkable growth of lesion in serial examination, and persistent symptoms, such as pain, is resection, which can be done open or laparoscopic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) appears in 3% of the population and is usually observed in women aged 20–50 years. However, it can also affect males and individuals of other ages. The benign mass regularly appears solitary in the right lobe of the liver. Changes in sinusoidal pressure and perfusion can induce reactive hyperplasia in the liver parenchyma, leading to FNH formation. Therefore, studies have shown a greater incidence of FNH in patients with vascular malformations; however, it is also seen in healthy patients without any predisposing factors [1, 2, 4]. Among previously reported cases, some mentioned a chronic usage of oral contraceptives in patients.

These patients are mostly asymptomatic, and the lesions are detected incidentally. Occurrence of FNH in children is rare; however, case reports show possible connections between the lesion and celiac disease, anticardiolipin or antiphospholipid antibodies, and hematologic malignancies [3]. Pedunculated FNH, accounting for 9% of all FNH cases, is a rare manifestation that presents with an exophytic growth attached to the liver by a pedicle and makes it challenging to diagnose the lesion. While FNHs constitute only 2–7% of all hepatic tumors in children, we experienced an extensive pedunculated focal nodular hyperplasia in a healthy 9-year-old girl [4]. This article intends to emphasize the occurrence of FNH in healthy children and discuss the possible role of in vitro fertilization (IVF).

Case presentation

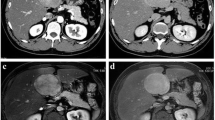

A 9-year-old Persian girl complaining of burning pain in the epigastrium, palpitations, and no other symptoms presented to our department. The nonpositional pain started 6 months before our visit and was not related to feeding or transit. She was referred to us by a cardiologist after a palpable mass in the right upper quadrant (RUQ) was detected. She did not mention any drug usage, allergies, or past medical or family history except the fact that she was born as a result of in vitro fertilization (IVF). On the physical examination and routine laboratory tests, which are reported below in the box, the only noticeable finding was a mild bulging in the RUQ. We performed an ultrasonography (US), demonstrating a large echogenic mass with moderate vascularity adjacent to the segment VI of the liver. A few days later, on the computed tomography (CT), a large, well-circumscribed mass (92 mm × 70 mm) without hemorrhage, hypervascular in portal phase with a central nonenhanced scar was present and seemed to emanate from the right liver lobe (Fig. 1). The lesion was hypodense in the precontrast phase and isoattenuated to the liver parenchyma in the equilibrium phase. The fibrotic scar demonstrated enhancement on the delayed scan. Based on the CT findings, pedunculated liver focal nodular hyperplasia and hepatocellular adenoma were considered. We checked for alpha fetoprotein and antihydatid antibody levels, which were both normal. For a decisive diagnosis and histopathological examination, the patient underwent surgery. Opening the abdomen, a large lesion was observed below the right lobe of the liver (Fig. 2). The lesion was resected, and macroscopic evaluation of the liver mass revealed a well-demarcated, solitary brown‒orange lesion with a central scar (Fig. 3A). No evidence of recurrence was detected on examination and US at the 1 month follow-up. Microscopic sections revealed a well-differentiated hepatocellular lesion with fibrous septa containing artery branches, a ductular reaction, and mixed inflammation. Nuclear pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, and mitotic figures were absent (Fig. 3B–D). The above-mentioned morphologic features suggested FNH.

Macroscopic and microscopic view of the mass. Macroscopic and microscopic view of the mass. A A well-demarcated, solitary brown–orange lesion with a central scar. B Focal nodular hyperplasia is composed of bland hepatocytes surrounded by fibrous septa, pointed by arrows, containing artery branches. C A med large-sized, thick walled muscular vessel with hyperplastic changes is demonstrated by the arrow. D The arrow points to ductular reaction that is a characteristic feature of focal nodular hyperplasia

Discussion

FNH is a benign lesion accounting for 8% of all nonhemangiomatous liver masses. The exact etiology of the lesion is still under debate, but it seems that hypoperfusion or hyperperfusion in the liver due to arterial malformation and changes in perfusion can cause a regenerative hyperplastic response in normal hepatocytes, leading to FNH [1]. FNH is often asymptomatic but can present as abdominal pain or a tender abdominal mass, especially when the lesion is larger than 10 cm [1, 5]. Same as our study, a few cases reported an uncommon pedunculated lesion of the liver, which is susceptible to torsion or becoming symptomatic and causing intraperitoneal hemorrhage. Navarini et al. reported a 26-year-old female presenting with an acute abdomen caused by pedicle torsion of a pedunculated FNH [6]. FNH is mainly reported in children with certain risk factors, such as chemotherapy, hematologic cancers, underlying liver disease, and history of radiotherapy; however, a previous case reported a healthy child with no medical history but who was born prematurely [7]. We experienced FNH in a child who was born following IVF, and we assume that there might be a correlation between IVF and FNH in a healthy child. Identical to the controversial effect of oral contraceptives on FNH, which is still not definite, more investigation is needed to find the possible connection between IVF and FNH [8,9,10].

Most often, laboratory data do not provide a conclusive diagnosis of FNH. However, there might be a slight rise in gamma-glutamyl transferase levels in some cases [4]. US is usually the initial imaging method with low sensitivity, performed when doubting FNH. However, a previous study showed a 96% success rate for contrast-enhancing US in ruling out hepatic adenoma. The US demonstrates an isoechoic or hypoechoic mass with a hyperechoic central scar relative to the liver parenchyma. Another widely used modality is triphasic helical CT with and without contrast agent, in which lesions appear hypodense or isodense before contrast agent administration, hyperdense during the arterial phase, and hypodense during the venous phase. The magnetic resonance imaging with hepatocyte scintigraphy with a sensitivity and specificity of 99% and 100% is the most accurate imaging modality for diagnosing the FNH. Using hepatocyte specific contrast agents, such as gadobenate dimeglumine, makes the lesion hyperintense relative to the normal liver parenchyma, which is particularly common in FNH [1, 7, 11]. Even using the imaging modalities, due to challenges in diagnosing FNH, especially the pedunculated form, sometimes biopsy may be needed. For instance, in a 35-year-old female, fine needle aspiration ruled out a gastrointestinal stromal tumor for a suspicious perigastric mass detected by CT [12,13,14].

At the time of presentation, our patient had an US revealing a hepatic mass. Due to the normal laboratory tests, tumor markers, the patient’s age, and imaging features of the lesion described earlier, malignant lesions were ruled out, and the mass was highly suspected to be FNH or hepatocellular adenoma, which the biopsy defined the mass to be FNH.

In asymptomatic, incidentally detected patients with FNH, only serial imaging is enough. In contrast, in pedunculated lesions at risk of rupture, torsion, intraperitoneal hemorrhage, continuous growth of the lesion, and becoming symptomatic, the patient should undergo surgery or biopsy [1, 3, 5]. Among the cases, one suggested a conservative management of an exophytic FNH [15], while another one described a rupture of projected FNH 3 years after the initial diagnosis, leading to resection of segment IV/V of the liver [16]. Before surgery, hepatic angiography may be conducted to reduce the vascularity of the tumor, as was done in the case reported by Khan et al. [17].

In a macroscopic view, the central scar is remarkable in FNHs and consists of mature collagen surrounded by vessels and fibrous septa; however, it may be absent in some cases. In microscopic view, multiple nodules of hepatocytes with granular cytoplasm between the fibrous septa can be seen. Bile ducts and Kupffer cells may also be present. Both hematoxylin and eosineosin (H&E) and reticulin stains can be helpful in diagnosing the tissue accurately [1,2,3, 7, 12]. A summary of the previously reported cases of the pedunculated FNH is presented in Table 1.

Conclusion

FNH, a common mass that appears in the liver in adulthood, can present as an exophytic pedunculated mass that increases the risk of intraperitoneal hemorrhage and rupture and can lead to misdiagnosis of the lesion as an extrahepatic mass, such as a gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Thus, surgical resection of the tumor is the treatment of the choice. Moreover, although rare, pedunculated FNH is a considerable differential diagnosis even in healthy children without any past medical history, presenting with epigastric or RUQ pain or tenderness.

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting this article are available in Razi Hospital Data center, Rasht, Iran.

Abbreviations

- FNH:

-

Focal nodular hyperplasia

- IVF:

-

In vitro fertilization

- RUQ:

-

Right upper quadrant

- US:

-

Ultrasonography

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

References

Hamad S, Willyard CE, Mukherjee S. Focal Nodular Hyperplasia. PubMed. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532244/. Accessed 11 Nov 2020.

Wasif N, Sasu S, Conway WC, Bilchik A. Focal nodular hyperplasia: report of an unusual case and review of the literature. Am Surg. 2008;74(11):1100–3.

Ji Y, Chen S, Xiang B, Wen T, Yang J, Zhong L, et al. Clinical features of focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62(6):813–8.

Tsalikidis C, Mitsala A, Pappas-Gogos G, Romanidis K, Tsaroucha AK, Pitiakoudis M. Pedunculated focal nodular hyperplasia: when in doubt, should we cut it out? J Clin Med. 2023;12(18):6034–44.

Alfayez A, Almodhaiberi H, Al Hussaini H, Alhasan I, Algarni A, Takrouni T. Hepatic focal nodular hyperplasia in a five-year-old healthy boy: a case report and literature review. Int J Hepatobil Pancr Dis. 2021;11(2):1–8.

Navarini D, Marcon F, Alcir L, Fornari F. Acute abdomen caused by a large pedunculated focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52(12):1513–4.

Koolwal J, Birkemeier KL, Zreik RT, Mattix KD. Pedunculated focal nodular hyperplasia in a healthy toddler. Baylor Univ Med Center Proc. 2018;31(1):97–9.

Ponnatapura J, Kielar A, Burke LMB, Lockhart ME, Abualruz AR, Tappouni R, et al. Hepatic complications of oral contraceptive pills and estrogen on MRI: Controversies and update—adenoma and beyond. Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;60:110–21.

Byrnes V, Cárdenas A, Afdhal N, Hanto D. Symptomatic focal nodular hyperplasia during pregnancy: a case report. Ann Hepatol. 2004;3(1):35–7.

Ben Ismail I, Zenaidi H, Jouini R, Rebii S, Zoghlami A. Pedunculated hepatic focal nodular hyperplasia: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9(6): e04202.

Dietrich CF, Schuessler G, Trojan J, Fellbaum C, Ignee A. Differentiation of focal nodular hyperplasia and hepatocellular adenoma by contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Br J Radiol. 2005;78(932):704–7.

Reddy K, Hooper K, Frost A, Hebert-Magee S, Bell W, Porterfield JR, et al. Pedunculated focal nodular hyperplasia masquerading as perigastric mass identified by EUS-FNA. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81(1):238–40.

Martiniuc A, Dumitraşcu T. Pedunculated focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver. Surg Gastroenterol Oncol. 2018;23(1):79.

Badea R, Meszaros M, Hajjar ALN, Rusu I, Chiorean L. Benign nodular hyperplasia of the liver-pedunculated form: diagnostic contributions of ultrasonography and consideration of exophytic liver tumors. J Med Ultrasonics. 2014;42(1):97–102.

Zeina AR, Glick Y. Pedunculated hepatic focal nodular hyperplasia. Ann Hepatol. 2016;15(6):929–31.

Kinoshita M, Takemura S, Tanaka S, Hamano G, Ito T, Aota T, et al. Ruptured focal nodular hyperplasia observed during follow-up: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2017;3(1):1–6.

Khan MR, Saleem T, Haq TU, Aftab K. Atypical focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver. eCommons—AKU (Aga Khan University). 2011;10(1):104–6.

Sawhney S, Jain R, Safaya R, Berry M. Pedunculated focal nodular hyperplasia. Pediatr Radiol. 1992;22(3):231–2.

Zhuang L, Ni C, Din W, Zhang F, Zhuang Y, Sun Y, et al. Huge focal nodular hyperplasia presenting in a 6-year-old child: a case presentation. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;29:76–9.

Akaguma A, Ishii T, Uchida Y, Chigusa Y, Ueda Y, Mandai M, et al. Laparoscopic resection for pedunculated focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver during pregnancy. Oxf Med Case Rep. 2023;2023(6):omad054.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

There was no funding, financial support, and sponsorship for this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PS, MM, MG, SP, NP, AZ, and MM were all contributed to this project by designing the study, data collection, drafting and revising the work. All authors are agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was provided by the Research Ethics Committees of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran on 10 January 2024. The approval ID is IR.GUMS.REC.1402.514.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s legal guardian for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

There is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Moayerifar, M., Samidoust, P., Gholipour, M. et al. Pedunculated focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver in a healthy child born following in vitro fertilization: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports 18, 185 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-024-04512-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-024-04512-4