Abstract

Background

Deviant behaviors are common during adolescence. Despite the diversity of juvenile delinquency, the patterns of deviant behaviors remain unclear in ethnic minorities. The present study aimed to evaluate the latent heterogeneity of deviant behaviors and associated factors in ethnic minority Yi adolescents.

Methods

The present study recruited a large sample of 1931 ethnic minority Yi adolescents (53.4% females, mean age = 14.7 years, SD 1.10) in five secondary schools in 2022 in Sichuan, China. The participants completed measures on 13 deviant behaviors and demographic characteristics, attitudinal self-control, and psychological distress. Sample heterogeneity of deviant behaviors was analyzed via latent class analysis using class as the cluster variable.

Results

The data supported three latent classes with measurement invariance by sex. 68.2%, 28.0%, and 3.8% of the sample were in the Normative, Borderline, and Deviant class, with minimal, occasional, and extensive deviant behaviors, respectively. The Deviant class was more prevalent in males (6.5%) than females (1.6%). There were significant class differences in domestic violence, school belonging, self-control, anxiety, and depressive symptoms. Males, domestic violence, low school belonging, and impaired self-control significantly predicted higher odds of the Deviant and Borderline classes compared to the normative class.

Conclusion

This study provided the first results on three latent classes of deviant behaviors with distinct profiles in ethnic minority adolescents in rural China. These results have practical implications to formulate targeted interventions to improve the psycho-behavioral functioning of the at-risk adolescents in ethnic minorities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adolescence is an important transitional life stage on the development of moral cognition and behaviors and adolescents are subject to various risk factors for delinquent behaviors [1]. Juvenile delinquency refers to adolescents’ engagement in deviant behaviors (such as fighting, cheating at school, and smoking) that violate social norms and values, and delinquent behaviors (such as theft, illicit drug use, and vandalism) that are illegal [2]. Juvenile delinquency is a growing societal issue around the world including China [3, 4], with potential impacts in terms of economic costs, public safety, and social dislocation. In the Chinese context, the minimum legal age for purchasing tobacco products is 18 years old. Smoking is commonly known as a harmful and addictive habit with various adverse health effects.

Deviant behaviors in adolescents have been associated with factors in the individual, family and school domains [5]. Empirical studies have found that lack of self-control is a key determinant of deviant behaviors in Chinese adolescents [6,7,8]. Direct and vicarious violent victimization, including experiences of domestic violence and witnessing violence, has been linked to an increased risk of juvenile delinquency [9]. Family functioning have been negatively correlated with deviant behavior [10] and family conflicts have been positively associated with mental health symptoms among Chinese adolescents [11].

School life plays an essential role in the academic, personal, and social development of adolescents [12]. A longitudinal study has linked lower levels of school belonging with higher rates of juvenile delinquency in American youths [13]. Besides, cultural factors, such as being part of an ethnic minority, could play a contributory role in deviant behaviors among adolescents. Ethnic minority status refers to being part of an ethnic group that is characterized by distinct cultural or ethnic attributes within the Chinese population. The relationship between deviant behaviors in adolescence and ethnic minority status is a complex and multifaceted issue. Research has shown higher rates of deviant behaviors among ethnic minority groups [14]. The relationships between deviant behaviors and ethnic minority status could be attributed to various factors in the economic (socioeconomic disadvantages), social (perceived prejudice and discrimination), cultural (cultural dissonance) domains [15,16,17,18].

The Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture in China comprises the largest population of ethnic Yi in China. Ethnic minorities in this area faced various social problems such as severe poverty, limited access to resources and opportunities, and rampant crime over the past century [19, 20]. In this region, parents tend to have lower education levels and often have to work outside the home for extended periods of time. These can make it challenging for them to closely monitor their children’s behavior and might contribute to lower levels of social control over adolescents. Ethnic minority adolescents in China have shown higher rates of illicit drug use and property delinquency than Han adolescents [21, 22]. A recent study conducted among Yi families in Liangshan highlights the need to provide culturally sensitive support among ethnic minority adolescents during family ethnic socialization [23]. Given the isolated geographical locations and mountainous terrain of this prefecture, it is a common practice of sending ethnic minority students away from their homes to attend boarding schools. This highlights the importance of school context for behavioral, cognitive, and psychological development of adolescents [24, 25]. A recent study has linked ethnic identity with mental health symptoms in ethnic minority Yi students [26]. Despite the potential importance and diversity of cultural contexts across ethnic minority groups, few studies in the Chinese context have investigated the heterogeneity of deviant behaviors in the context of ethnic minority adolescents.

Deviant behaviors in adolescents are often complex and multifaceted. Latent class analysis (LCA) is a person-oriented modeling technique that can identify distinct subgroups of adolescents based on their patterns of deviant behaviors [27]. This analytical approach is useful for examining the heterogeneity in deviant behaviors and informing the associated risk factors. A literature search on Web of Science on 7th January 2024 using keywords of (“juvenile delinquency” or “deviant behaviour” or “delinquent behaviour” or “antisocial behavior” or “risk behavior” (Title) and latent class (Title)) found 15 articles that used LCA to examine the latent heterogeneity of deviant behavior in samples of adolescents and sexual minority youths. None of these studies, however, are based on ethnic minority adolescents. In the Chinese context, recent studies [28, 29] have yet to utilize LCA to examine the latent heterogeneity of deviant behaviors of adolescents, particularly among ethnic minority adolescents.

In light of the research gaps, the present study first aimed to investigate the latent heterogeneity of deviant behaviors in ethnic minority adolescents in China. The second objective was to examine the differences among the derived latent classes in associated variables, including demographic, family, school characteristics, self-control, and mental health symptoms. This would lead to a better understanding of the risk factors of deviant behaviors among Chinese ethnic minority adolescents. There are two hypotheses in the present study. First, considering existing LCA findings in mainstream adolescents [30,31,32,33], we hypothesized that there would exist multiple latent classes of deviant behaviors in ethnic minority adolescents. Second, the derived latent classes would demonstrate significant profile differences in associated variables, as found in previous similar studies among children and runaway youths [34, 35].

Methods

Participants

In the present study, 1931 ethnic Yi adolescents aged 12 to 17 were recruited in the Liangshan Prefecture of Sichuan, China from June to July 2022. The overall response rate of the adolescents was 86.8%. The participants were recruited from 38 classes in five secondary schools with an average class size of 51 students. Inclusion criteria were ethnic minority status, Grade 7 or 8, and able to understand simplified Chinese. The study purpose was clearly explained to the adolescents and written informed consent was obtained from the adolescents and their legal guardians. Study participation was voluntary and the adolescents could withdraw from the study at any time without negative consequence. The collected information was anonymized to preserve data confidentiality. Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the first author’s university.

The required sample size was calculated according to Dziak, Lanza and Tan [36] where N = m(w2)80/w2. In this equation, the numerator denoted the value of N × w2 for which power exceeded 80% and the denominator denoted the square of effect size. For 13 binary items, m(w2)80 was estimated to be 62.3 and 57.1 for 3 and 5 classes, respectively. For w = 0.2 (low to medium values), the required sample size was 1558. The present sample size (N = 1931) provided at least 80% power for13-item, 3-class to 5-class LCA with w = 0.2.

Measures

The study questionnaire included questions on deviant behaviors, demographic, family and school characteristics, attitudinal self-control, and mental health. It was field tested in May 2022 and underwent minor revisions based on feedback from the adolescents.

In this study, deviant behaviors referred to engagement in behaviors that causes harm to others or property or puts oneself in a position that invites harm from being compromised/inebriated, or break certain rules, regulations or norms. Deviant behaviors were assessed via 13 binary (yes/no) items on the respondents’ engagement in deviant behaviors over the past year: stealing others’ properties (thief), vandalism of properties (vandalism), robbery of others’ properties (robbery), fighting, obtain money or property by fraud (fraudulence), playing online games for more than 5 h continuously (gaming addiction), cheating, runaway, truancy, drinking alcohol, illicit drug use, smoking, and gambling. The list of deviant behaviors was developed based on existing literature on juvenile delinquency in Chinese adolescents [11, 37, 38] and is shown in Supplementary Table 1. We adapted and modified the items based on the Code of Conduct for Middle School Students and Law on the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency in China to fit the Chinese ethnic contexts. The 1-factor model on deviant behaviors showed adequate model fit to the present sample with comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.98, root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.036, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.050. The 13 items had strong factor loadings (λ = 0.61–0.95, p < 0.01) and good reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.89) in the present sample.

Demographic characteristics assessed in the questionnaire included biological sex, age, religious belief, and urban registration (versus rural). Family characteristics included having a single parent and domestic violence via three self-constructed items such as “Family members are loudly reprimanded, insulted or humiliated” on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 = “never” to 5 = “always”. School belonging was assessed by six self-constructed items such as “I think I belong to the school I am currently at” and “My school is a great place” on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”. The 1-factor model on school belonging showed satisfactory model fit to the present sample with comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.98, root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.068, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.028. Acceptable to good reliability was found for the total score of domestic violence (α = 0.67) and school belonging (α = 0.86).

Attitudinal self-control was assessed via the Grasmick Low Self-Control Scale [39], which is a 23-item scale on six types of self-control trait. The present study included four subscales: impulsivity (3 items), risk seeking (4 items), self-centeredness (4 items), and temperament (4 items). The items are scored on a 4-point scale from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 4 = “strongly agree”. The Low Self-Control scale has been validated among adolescent samples in the Chinese context with good psychometric properties [8]. The 4-factor model showed good model fit to the data with CFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.036, and SRMR = 0.030 in the present sample with acceptable reliability (α = 0.64–0.81).

Anxiety and depressive symptoms were measured by the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), respectively, over the past two weeks [40, 41]. The items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 = “not at all” to 3 = “nearly every day”. The composite score for GAD-7 and PHQ-9 ranged from 0 to 21 and from 0 to 27, respectively. The cutoff scores for mild, moderate, and moderately severe anxiety/depression were represented by GAD-7/PHQ-9 scores of 5, 10, and 15, respectively. Both the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 have been validated in the Chinese context [42, 43]. The 1-factor model showed good model fit to the present sample for both GAD-7 with CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.027, and SRMR = 0.013 and PHQ-9 with CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.059, and SRMR = 0.034 with good reliability (α = 0.88–0.91).

Data analysis

Prevalence of deviant behaviors was compared across sex via chi-square tests. There were no missing data in the 13 deviant behaviour items. The 13 deviant behaviors showed a mean intraclass correlation of 0.077 within the class. Given the clustered nature, LCA was conducted under the TYPE = COMPLEX option with class as a cluster variable in Mplus 8.6 to adjust for non-independence in chi-square statistic and standard errors. The LCA model assumes that the observed variables are categorical, and that the latent classes are mutually exclusive and exhaustive. The deviant behaviors were assumed conditionally independent of each other within each latent class [44].

One-class to 5-class LCA models were estimated on the 13 deviant behaviors using robust maximum likelihood estimator [45]. Model fit was evaluated using Bayesian information criterion (BIC), sample-size adjusted Bayesian information criterion (aBIC), and bivariate log-likelihood chi-square (TECH10) with lower values indicating better fit. The Lo–Mendell–Rubin (LMR) likelihood ratio test [46] compared the fit of the k-class LCA model to the alternative k-1 class model with a p-value < 0.05 favoring the k-class model. Model classification quality was assessed using entropy and average latent class probabilities, with values of at least 0.80 and 0.90 indicating adequate classification, respectively. Sample heterogeneity in deviant behaviors was reported via prevalence and conditional item probabilities of latent classes. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.01 level in this study to address multiple testing.

LCA models were estimated separately by sex to test the stability of latent class structure. Measurement invariance was evaluated by comparing BIC of the LCA models with and without equality constraints on the item thresholds. The latent classes were compared in terms of demographic, family, and school characteristics, attitudinal self-control, and mental health symptoms. Class differences were estimated using the Bolck, Croon, and Hagenaars (BCH) method [47] with post-hoc comparisons using Sidak correction. 3-step multinomial logistic regression was conducted on the latent class memberships using demographic, family, school characteristics, and low self-control as predictors. The associations were estimated by adjusted odds ratios (OR), which were regarded as statistically significant if the 95% confidence interval (CI) excluded one.

Results

Sample characteristics

As Table 1 shows, half (53.4%) of the sample was females, and the average age was 14.7 years (SD 1.08). Most of them had a rural registration (95.7%) and one-eighth (13.1–13.2%) of them had religious belief and a single parent. Overall, the levels of school belonging, and self-control of the sample were moderate. The mean score for GAD-7 and PHQ-9 was 4.77 (SD 4.51) and 6.61 (5.08), respectively. The proportion of adolescents with minimal, mild, moderate, and moderately severe anxiety symptoms was 53.8%, 33.5%, 9.0%, and 3.7%, respectively. The corresponding proportion was 37.6%, 41.3%, 13.9%, and 7.1%, respectively, for depressive symptoms. As Supplementary Table 1 shows, the prevalence of deviant behaviors ranged from 2.8 to 31.6%. Higher prevalence (29.6–31.6%) was found for cheating at school and gaming addiction; while illicit drug use, robbery, fraudulence, and gambling were among the least common (2.8–5.3%). Males showed significantly higher prevalence in most deviant behaviors (χ2(1) = 15.2–258.0, p < 0.01) except for cheating and runaway than females.

Latent class analysis models

Table 2 shows the fit indices of the LCA models in the whole sample and across sex. Substantial decreases in BIC and aBIC were found from 1-class to 3-class LCA models, after which the ICs levelled off. The 3-class, 4-class, and 5-class LCA models showed comparable BIC and the 3-class LCA model showed the minimum BIC in the male and female subsamples. The 4-class and 5-class LCA models showed lower bivariate log-likelihood chi-squares with fewer significant standardized residuals. The LMR likelihood ratio test results consistently pointed to the 3-class solution in the whole sample and across sex with a significantly better fit than the 2-class solution and comparable model fit as the 4-class solution (p = 0.33–0.59). Moreover, the 3-class LCA model showed higher entropy (0.83–0.84) than the 4-class model (0.72–0.80). These findings supported the 3-class LCA model in terms of BIC, LMR test, and entropy. The multiple-group LCA model with sex-invariant item thresholds showed comparable model fit in terms of BIC (18,069 versus 18,064) as the configural model with non-invariant item thresholds, supporting measurement invariance of latent class structure across sex.

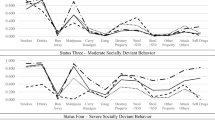

As Fig. 1 shows, the normative class comprised 68.2% of adolescents and had very low probabilities (0.0–5.4%) in all deviant behaviors except for gaming addiction and cheating (16.2%). The Borderline class comprised 28.0% of adolescents and showed substantial probabilities in fighting, gaming addiction, cheating, and truancy (45.2–62.0%). This class showed non-negligible probabilities in vandalism, runaway, drinking, and smoking (28.6–38.5%) but low probabilities in thief, robbery, fraudulence, illicit drug use, and gambling (1.9–17.4%). The smallest class comprised 3.8% of adolescents and was labelled the Deviant class. This class had the highest conditional item probabilities (58.9–93.0%) of all deviant behaviors.

Comparison of latent classes

As Table 3 shows, males were significantly more prevalent (p < 0.01) in the Deviant and Borderline class than normative class. No significant differences (χ2(2) = 1.32–2.70, p = 0.26–0.52) were found in other demographic variables. Significant differences (χ2(2) = 42.6–147.9, p < 0.01) were found across the three classes in domestic violence, school belonging, self-control, GAD7, and PHQ9 symptoms. Both Borderline and Deviant classes showed significantly lower levels of school belonging and self-control and higher levels of domestic violence, and GAD7 and PHQ9 symptoms than the Normative class. Moreover, the Deviant class showed significantly lower levels of school belonging and higher levels of domestic violence, risk seeking, self-centeredness, and GAD7 and PHQ9 symptoms than the Borderline class. Supplementary Table 2 shows significant differences (p < 0.01) in the prevalence of at least moderate anxiety symptoms (Normative class: 7.7%; Borderline class: 18.9%; Deviant class: 51.5%) and moderate depressive symptoms (Normative class: 12.9%; Borderline class: 32.8%; Deviant class: 67.9%).

Predictors of latent classes memberships

In Table 4, having a single parent was not significantly associated (p > 0.05) with the latent class memberships. Males had significantly higher odds in Borderline class (OR = 4.80, 95% CI 3.46–6.64, p < 0.001) and Deviant class (OR = 10.6, 95% CI 4.32–26.3, p < 0.001) compared to Normative class than females. Compared to Normative class, school belonging was significantly associated with lower odds of Borderline class (OR = 0.47, 95% CI 0.37–0.60, p < 0.001) and Deviant class (OR = 0.42, 95% CI 0.30–0.59, p < 0.001). Temperament were significantly associated with higher odds of Borderline class (OR = 1.97, 95% CI 1.44–2.68, p < 0.001) and Deviant class (OR = 1.92, 95% CI 1.20–3.07, p < 0.01) compared to Normative class. Domestic violence was significantly associated with higher odds of Deviant class compared to Normative class (OR = 6.52, 95% CI 3.54–12.0, p < 0.001) and Borderline class (OR = 2.57, 95% CI 1.78–3.72, p < 0.001). Risk-seeking was significantly associated with higher odds of Borderline class (OR = 1.34, 95% CI 1.10–1.63, p < 0.01) compared to Normative class. Self-centeredness was significantly associated with higher odds of Deviant class (OR = 2.25, 95% CI 1.32–3.84, p < 0.01) compared to Borderline class. Sensitivity analysis was conducted by including religious belief and urban registration as control variables in the multinomial logistic regression and the results were highly similar to those in Table 4.

Discussion

The present study characterized the latent heterogeneity of deviant behaviors and reported the first results on the three latent (Normative, Borderline, and Deviant) classes in a minority population of Chinese adolescents. The three latent classes showed distinct profiles of deviant behaviors and significant relationships with external variables. The majority of the adolescents were in the Normative class with minimal probabilities of deviant behaviors, higher levels of school belonging and self-control and lower levels of domestic violence and mental distress. A quarter of the sample belonged to the Borderline class with moderate probabilities in deviant behaviors (i.e. fighting, gaming addiction, cheating, and truancy). A longitudinal study has found temporal associations between deviant behaviors and school engagement and community violence exposure [48]. Further longitudinal research is needed to track the developmental trajectories of deviant behaviors among the adolescents and investigate potential risk factors of the transition from the Borderline class to the Deviant class in the future.

The Deviant class showed high probabilities in all deviant behaviors. Despite its low prevalence (3.8%), adolescents in this class showed the highest exposure to domestic violence and impairment in school belonging and self-control. More than half of this class had at least moderate levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms, which indicated substantial mental health needs for this class with poorer family and school functioning. The present study found a higher prevalence of Deviant class in males than females. This is consistent with the sex difference in deviant behaviors found in adolescents with higher levels of sensation-seeking and lower levels of impulse control in young men than young women [49, 50]. Existing studies [51, 52] have shown potential impact of domestic violence on self-control among children and adolescents. On the one hand, exposure to violence could decrease self-regulation abilities. On the other hand, low self-control could aggravate conflict within the family and contribute to domestic violence. Future research should elucidate the possible bidirectional relationships between domestic violence and self-control.

The present study identified factors associated with the latent class of deviant behavior. Our positive associations between impaired self-control and deviant behavior are in line with previous findings [53]. While risk-seeking and temperament were found to distinguish the Normative class from the other two classes, adolescents who were more self-centeredness showed significantly higher odds in Deviant class relative to Borderline class. Thus, interventions aimed at promoting self-control and reducing self-centeredness could be implemented both within families and schools. Family cohesion programs could be implemented to promote positive family relationships and reduce the risk of domestic violence. Positive youth development programs could be implemented in schools to promote self-control and a sense of school belonging among adolescents [54, 55]. These interventions could potentially help reduce the risk of deviant behavior among ethnic minority adolescents.

Throughout history, Chinese ethnic minorities have exhibited unique behavioral characteristics. Few studies have systematically analyzed their patterns of deviant behaviors and associated risk factors in social and individual domains. As Yi [56] pointed out, arbitrarily attributing poor minority performance to a striking feature of mainstream discourse is incorrect. This can lead to attributing the poverty and delinquency of the ethnic minority individuals solely to their cultural and social characteristics, which can create more vicious circles based on their psychosocial symptoms. In comparison to assimilation, the ethnic minority in China has been delineated as experiencing “borderline integration” [57]. To avoid intensifying the marginalization of ethnic minorities within the wider society, systematic research is necessary to elucidate the psycho-behavioral characteristics of ethnic minorities, identify potential risk and protective factors, and inspire more feasible intervention practices for their development in China. Further studies should compare the deviant behaviors of adolescents across ethnicity groups and investigate the role of acculturation in the well-being of adolescents across diverse ethnic backgrounds [58,59,60].

In the past decade, various poverty alleviation and rural revitalization policies have been implemented in the ethnic minority areas in China, which led to rapid development and substantial improvements in material lives [61, 62]. Apart from economic development of impoverished regions, it is crucial to enhance psycho-behavioral well-being of the adolescents for a holistic development. Our study provides insights into interventions for deviant behaviors among ethnic minority adolescents. Policymakers and practitioners should prioritize adolescents with lower levels of school belonging, exposure to domestic violence, higher levels of mental distress and tendencies towards risk-seeking and self-centeredness, and temperament. Our findings call for a greater emphasis to promote mental wellness among ethnic minorities. This could be achieved via adjustment of cultural and societal norms and beliefs about family structures, roles, and dynamics within ethnic minority communities to foster inclusive and harmonious family environments. A supportive school environment should be constructed by introducing professional teaching staff, educational psychologists, and school social workers in ethnic minority contexts. A comprehensive education curriculum should not only focus on academic achievement but also on the personal and psycho-behavioral development of adolescents to enhance their overall school learning experience.

Limitations and future directions

There were several limitations in this study. First, the cross-sectional design did not permit inference of the directional relationship between deviant behaviors and school belonging and mental distress. Deviant behaviors could lead to less school belonging and greater mental health symptoms. Longitudinal studies are needed to clarify the temporal associations between deviant behaviors with associated factors and development of deviant behaviors across adolescence and early adulthood. Second, similar to other Chinese studies [63, 64], the present study assessed deviant behaviors using a self-constructed scale. Despite the adequate psychometric properties, our new instrument was examined only based on an ethnic minority sample, so its usefulness as an assessment tool of deviant behaviors was restricted to this population and our present findings may not generalize to other populations. Measurement invariance and normative scores should be established across ethnicity groups before valid comparisons could be made with data from other populations. Third, all the study variables were self-reported by the adolescents, which may introduce common method bias. The non-random sampling of the present ethnic Yi sample implies potential selection and response biases. The results might not generalize to other ethnic minority groups. Future studies should incorporate assessments rated by parents and teachers and objective biomarkers to improve the validity of the measures.

Fourth, the LCA model assumed the observed variables to be conditionally independent within each latent class. However, the relationships among deviant behaviors might not be solely explained by the latent class variable. Violation of this assumption could bias the latent class structure, class assignment, and parameter estimates. Future studies could estimate the significant standardized residuals in the LCA model as sensitivity analyses to replicate the present results. Fifth, though our study analysis properly accounted for the clustering nature of adolescents nested within the class, the present sample was recruited from only five schools. The low school size did not permit us to systematically examine the variation in deviant behavior at the school level. Further large-scale studies are recommended among adolescents from more schools to conduct multilevel LCA in deviant behaviors at the school level. Sixth, adolescents could engage in deviant behaviors due to peer influence and social pressure. The present study did not examine peer influence as a motive for deviant behaviors. Future studies should examine the associations between social factors (peer influence and bullying victimization) and macro-level factors (stereotypes and culture) and deviant behaviors in the Borderline and Deviant classes.

Availability of data and materials

All data analysed during this study are included in this published article as supplementary materials. The Mplus syntax scripts are available from the first authors upon request by email.

References

Klopack ET, Simons RL, Simons LG. Puberty and girls’ delinquency: a test of competing models explaining the relationship between pubertal development and delinquent behavior. Justice Q. 2020;37(1):25–52.

Childs KK, Sullivan CJ, Gulledge LM. Delinquent behavior across adolescence: investigating the shifting salience of key criminological predictors. Deviant Behav. 2010;32(1):64–100.

Young S, Greer B, Church R. Juvenile delinquency, welfare, justice and therapeutic interventions: a global perspective. Bjpsych Bulletin. 2017;41(1):21–9.

Weng X, Ran M-S, Chui WH. Juvenile delinquency in Chinese adolescents: an ecological review of the literature. Aggress Violent Beh. 2016;31:26–36.

Crosnoe R, Erickson KG, Dornbusch SM. Protective functions of family relationships and school factors on the deviant behavior of adolescent boys and girls—reducing the impact of risky friendships. Youth Soc. 2002;33(4):515–44.

Chan HC, Chui WH. The influence of low self-control on violent and nonviolent delinquencies: a study of male adolescents from two Chinese societies. J Forensic Psychiatry Psychol. 2017;28(5):599–619.

Lu Y-F, Yu Y-C, Ren L, Marshall IH. Exploring the utility of self-control theory for risky behavior and minor delinquency among chinese adolescents. J Contemp Crim Justice. 2013;29(1):32–52.

Weng X, Chui WH. Assessing two measurements of self-control for juvenile delinquency in China. J Contemp Crim Justice. 2018;34(2):148–67.

Lin WH, Cochran JK, Mieczkowski T. Direct and vicarious violent victimization and juvenile delinquency: an application of general strain theory. Sociol Inq. 2011;81(2):195–222.

Shek DTL, Lin L. What predicts adolescent delinquent behavior in Hong Kong? A longitudinal study of personal and family factors. Soc Indic Res. 2016;129(3):1291–318.

Liu T-H, De Li S, Zhang X, Xia Y. The spillover mechanisms linking family conflicts and juvenile delinquency among Chinese adolescents. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2020;64(2–3):167–86.

Roeser RW, Eccles JS, Sameroff AJ. School as a context of early adolescents’ academic and social-emotional development: a summary of research findings. Elem Sch J. 2000;100(5):443–71.

Bender K. The mediating effect of school engagement in the relationship between youth maltreatment and juvenile delinquency. Child Sch. 2012;34(1):37–48.

Burnside AN, Gaylord-Harden NK. Hopelessness and delinquent behavior as predictors of community violence exposure in ethnic minority male adolescent offenders. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2019;47(5):801–10.

Chavez JM, Rocheleau GC. Formal labeling, deviant peers, and race/ethnicity: an examination of racial and ethnic differences in the process of secondary deviance. Race Justice. 2020;10(1):62–86.

Bennett M, Roche KM, Huebner DM, Lambert SF. Peer discrimination, deviant peer affiliation, and latino/a adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms: a prospective study. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2022.2093209.

Weinstein M, Jensen MR, Tynes BM. Victimized in many ways: online and offline bullying/harassment and perceived racial discrimination in diverse racial-ethnic minority adolescents. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2021;27(3):397–407.

Yao J, Yang LP. Perceived prejudice and the mental health of Chinese ethnic minority college students: the chain mediating effect of ethnic identity and hope. Front Psychol. 2017;8:247258.

Cao M, Xu D, Xie F, Liu E, Liu S. The influence factors analysis of households’ poverty vulnerability in southwest ethnic areas of China based on the hierarchical linear model: a case study of Liangshan Yi autonomous prefecture. Appl Geogr. 2016;66:144–52.

Cheng W, Rao Y, Tang Y, Yang J, Chen Y, Peng L, Hao J. Identifying the Spatio-temporal characteristics of crime in liangshan prefecture, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(17):10862.

Yang L, Muer C, Hama R, Chen XL, Yuan B, Ma Y. Illicit drug use and awareness of Yi and Han students in Sichuan Liangshan area. Chin J School Health. 2016;37(5):647–50.

Wu YN, Chen XJ, Qu J. Explaining Chinese delinquency: self-control, morality, and criminogenic exposure. Crim Justice Behav. 2022;49(4):570–92.

Yao H, Hou Y, Hausmann-Stabile C, Lai AHY. Intergenerational ambivalence, self-differentiation and ethnic identity: a mixed-methods study on family ethnic socialization. J Child Family Stud. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-024-02819-w.

Leibold J. Interior ethnic minority boarding schools: China’s bold and unpredictable educational experiment. Asian Stud Rev. 2019;43(1):3–15.

Chang F, Huo Y, Zhang S, Zeng H, Tang B. The impact of boarding schools on the development of cognitive and non-cognitive abilities in adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1852.

Lai AHY, Lam JKH, Yao H, Tsui E, Leung C. Effects of students’ perception of teachers’ ethnic-racial socialization on students’ ethnic identity and mental health in rural China’s schools. Front Psychol. 2024. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1275367.

Lanza ST, Cooper BR. Latent class analysis for developmental research. Child Dev Perspect. 2016;10(1):59–64.

Xu X, Sun IY, Wu Y. Strain, depression, and deviant behavior among left-behind and non-left-behind adolescents in China. Int Sociol. 2023;38(3):394–410.

Chen L, Chen X, Zhao S, French DC, Jin S, Li L. Predicting substance use and deviant behavior from prosociality and sociability in adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2019;48(4):744–52.

Cho S, Lacey B, Kim Y. Developmental trajectories of delinquent peer association among Korean adolescents: a latent class growth analysis approach to assessing peer selection and socialization effects on online and offline crimes. J Contemp Crim Justice. 2021;37(3):379–405.

Luther AW, Leatherdale ST, Dubin JA, Ferro MA. Classifying patterns of delinquent behaviours and experiences of victimization: a latent class analysis among children. Child Youth Care Forum. 2023;53:693.

Nasaescu E, Zych I, Ortega-Ruiz R, Farrington DP, Llorent VJ. Longitudinal patterns of antisocial behaviors in early adolescence: a latent class and latent transition analysis. Eur J Psychol Appl Legal Context. 2020;12(2):85–92.

Ang RP, Li X, Huan VS, Liem GAD, Kang T, Wong QY, Yeo JYP. Profiles of antisocial behavior in school-based and at-risk adolescents in Singapore: a latent class analysis. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2020;51(4):585–96.

Luther AW, Leatherdale ST, Dubin JA, Ferro MA. Classifying patterns of delinquent behaviours and experiences of victimization: a latent class analysis among children. Child Youth Care Forum. 2024;53(3):693–717.

Jeanis MN, Fox BH, Muniz CN. Revitalizing profiles of runaways: a latent class analysis of delinquent runaway youth. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2019;36(2):171–87.

Dziak JJ, Lanza ST, Tan XM. Effect size, statistical power, and sample size requirements for the bootstrap likelihood ratio test in latent class analysis. Struct Eq Model A Multidiscip J. 2014;21(4):534–52.

Shek DTL, Zhu XQ. Paternal and maternal influence on delinquency among early adolescents in Hong Kong. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(8):1338.

Wan GW, Tang SS, Xu YC. The prevalence, posttraumatic depression and risk factors of domestic child maltreatment in rural China: a gender analysis. Children Youth Serv Rev. 2020;116:1052.

Arneklev BJ, Grasmick HG, Tittle CR, Bursik RJ. Low self-control and imprudent behavior. J Quant Criminol. 1993;9:225–47.

Mossman SA, Luft MJ, Schroeder HK, Varney ST, Fleck DE, Barzman DH, et al. The generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale in adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder: signal detection and validation. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2017;29(4):227–34.

Martin A, Rief W, Klaiberg A, Braehler E. Validity of the brief patient health questionnaire mood scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(1):71–7.

Sun J, Liang K, Chi X, Chen S. Psychometric properties of the generalized anxiety disorder scale-7 item (GAD-7) in a large sample of Chinese adolescents. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(12):1709.

Xiong N, Fritzsche K, Wei J, Hong X, Leonhart R, Zhao X, et al. Validation of patient health questionnaire (PHQ) for major depression in Chinese outpatients with multiple somatic symptoms: a multicenter cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:636–43.

Weller BE, Bowen NK, Faubert SJ. Latent class analysis: a guide to best practice. J Black Psychol. 2020;46(4):287–311.

Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 8th ed. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2017.

Nylund KL, Asparoutiov T, Muthen BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct Eq Model A Multidiscip J. 2007;14(4):535–69.

Bakk Z, Tekle FB, Vermunt JK. Estimating the association between latent class membership and external variables using bias-adjusted three-step approaches. Sociol Methodol. 2013;43(1):272–311.

Lin S, Yu C, Chen J, Zhang W, Cao L, Liu L. Predicting adolescent aggressive behavior from community violence exposure, deviant peer affiliation and school engagement: a one-year longitudinal study. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;111: 104840.

Liu XR, Kaplan HB. Explaining the gender difference in adolescent delinquent behavior: a longitudinal test of mediating mechanisms. Criminology. 1999;37(1):195–215.

Shulman EP, Harden KP, Chein JM, Steinberg L. Sex differences in the developmental trajectories of impulse control and sensation-seeking from early adolescence to early adulthood. J Youth Adolesc. 2015;44(1):1–17.

Willems YE, Li JB, Hendriks AM, Bartels M, Finkenauer C. The relationship between family violence and self-control in adolescence: a multi-level meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(11):2468.

Finkenauer C, Buyukcan-Tetik A, Baumeister RF, Schoemaker K, Bartels M, Vohs KD. Out of control: identifying the role of self-control strength in family violence. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2015;24(4):261–6.

Connolly EJ, Al-Ghamdi MS, Kobeisy AN, Alqurashi F, Schwartz JA, Beaver KM. Identifying latent classes of antisocial behavior among youth from Saudi Arabia: an assessment of the co-occurrence between aggression, psychopathy, low self-control, and delinquent behavior. Youth Violence Juvenile Justice. 2017;15(3):219–39.

Williams JL, Anderson RE, Francois AG, Hussain S, Tolan PH. Ethnic identity and positive youth development in adolescent males: a culturally integrated approach. Appl Dev Sci. 2014;18(2):110–22.

Curran T, Wexler L. School-based positive youth development: a systematic review of the literature. J Sch Health. 2017;87(1):71–80.

Yi L. Ethnicization through schooling: the mainstream discursive repertoires of ethnic minorities. China Quart. 2007;192:933–48.

Heberer T. China and its national minorities: autonomy or assimilation. 1st ed. United Kingdom: Routledge; 2017.

Diaz T, Bui NH. Subjective well-being in Mexican and Mexican American Women: the role of acculturation, ethnic identity, gender roles, and perceived social support. J Happiness Stud. 2017;18(2):607–24.

Lokhande M, Reichle B. Acculturation and school adjustment of children and youth from culturally diverse backgrounds: predictors and interventions for school psychology. J Sch Psychol. 2019;75:1–7.

Areba EM, Watts AW, Larson N, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Acculturation and ethnic group differences in well-being among Somali, Latino, and among adolescents. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2021;91(1):109–19.

Yin X, Meng Z, Yi X, Wang Y, Hua X. Are, “Internet+” tactics the key to poverty alleviation in China’s rural ethnic minority areas? Empirical evidence from Sichuan Province. Financ Innov. 2021;7(1):30.

Gu R, Zhang W, Chen K, Nie F. Can information and communication technologies contribute to poverty reduction? Evidence from poor counties in China. Inform Technol Dev. 2023;29(1):128–50.

Wang Y, Ma S, Jiang L, Chen Q, Guo J, He H, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and deviant behaviors among Chinese rural emerging adults: the role of social support. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):2404.

Jin X, Chen W, Wu Y. A study of deviant behaviour among China’s left-behind children: the impact of strain, social control and learning. Child Family Social Work. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.13085.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their appreciation to all adolescents for their participation in the study, and the school principals and teachers for their help in the study coordination and the useful comments from the reviewers.

Funding

The work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (Grant No. 22CSH068), a ChiangKiang visiting scholar program (for Yip) and General Research Fund Grants (17608522; 17603323) by the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kunjie Cui: conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, and writing—original draft. Ted C.T. Fong: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software; visualization, and writing—original draft. Paul S.F. Yip: conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, resources, supervision, validation, and writing–review & editing. All authors have provided critical comments and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with ethical standards of relevant institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Declaration of Helsinki in 1975, as revised in 2008. Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Southwestern University of Finance and Economics. All adolescent participants provided voluntary written assent and family guardians provided consent for the adolescent to join the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, K., Fong, T.C. & Yip, P.S.F. Latent heterogeneity of deviant behaviors and associated factors among ethnic minority adolescents: a latent class analysis. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 18, 93 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-024-00771-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-024-00771-7