Abstract

This study aims to enhance the understanding of how servant leadership (SL) influences organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) in the specific context of Chinese private enterprises. Applying social exchange theory, social identity theory, and psychological contract theory, this study examines not only the mediating roles of relational identification and perceived organizational support (POS) but also how workplace loneliness negatively moderates the sequential mediating effect of SL on OCB. The analyzed survey included 335 employees from private enterprises in Zhejiang Province, China. Partial least squares structural equation modeling results show that relational identification and POS sequentially mediate the relationship between SL and OCB. Moreover, workplace loneliness significantly moderated these relationships. By presenting a framework that captures sequence mediation and includes a moderator, this study not only contributes methodologically to its field of study but also extends the literature by providing critical theoretical and practical insights for leadership and organizational behavior studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the beginning of the 21st century, China’s economic landscape has undergone significant transformations, marked in particular by a rising tide of uncertainty. In this dynamic environment, private enterprises have emerged as crucial drivers of the Chinese economy. Such enterprises contribute significantly to tax revenues, private investments, patent innovations, job opportunities, and the overall count of business entities (Liu and Wang, 2021). Despite their pivotal role, private enterprises operate under the pressures of self-financing and management autonomy, making them vulnerable to poor decision-making, which could lead to bankruptcy (Huang, 2013). Consequently, the stakes for survival and competitiveness have escalated, presenting formidable challenges to the sustained growth of these enterprises (Chen, 2020). Merely fulfilling one’s job responsibilities is no longer sufficient to ensure competitiveness in this context. To thrive amid these challenges, private enterprises must prioritize innovation, agility, and adaptability to swiftly respond to evolving market dynamics (Huang, 2013). In essence, continuous innovation, rapid adaptation, and increased competitiveness have become imperative for the survival and success of private enterprises in China’s rapidly changing economic landscape.

Organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) is a kind of voluntary action performed by employees that is not mandated by formal job descriptions and is not motivated by the organization’s official reward program to benefit the organization (Organ, 1988). OCB has been proven to play a key role in enhancing organizational performance, fostering innovation capabilities, and boosting competitiveness (Zhao et al., 2019). As OCB has emerged as a vital element for organizational success, a fundamental question that arises is how to effectively encourage employees to participate in and promote higher levels of such behavior within the organization (Choong and Ng, 2022).

Previous studies have established that leadership styles, particularly servant leadership, significantly influence OCB (Aboramadan et al., 2022). Servant leadership underscores the leader’s original intention and responsibility in serving employees, focusing on their well-being and development, which in turn encourages employees’ positive behavior such as increased OCB. Despite the beneficial effects of servant leadership on OCB being well-recognized, a fundamental question remains unanswered: what precise mechanisms, such as relational identification and perceived organizational support (POS), could drive the relationship between servant leadership and OCB? There remains a need to explore the underlying mechanisms that shape these relationships, especially within the context of China’s private enterprises. In China, enterprises are accustomed to implementing a paternalistic leadership style, and employees are accustomed to following the instructions of their leaders (Wang, 2022a). According to Wang’s (2022a) review, paternalistic leadership is a style similar to patriarchy, characterized by strict discipline and authority. In traditional Chinese society, authoritarianism represents the absolute obedience of subordinates to the authority of their superiors. When this value is reflected in business management, it manifests as subordinates’ compliance with the authoritative behavior of their superiors (Fan and Zheng, 2000; Wang, 2022a). This directive leadership style can lead employees to rely on leaders’ instructions and decisions (Zhang et al., 2011) rather than demonstrating autonomous OCB and may even result in compulsory citizenship behavior (Song, 2020). Understanding these mechanisms could offer actionable insights for addressing the challenges encountered by these firms.

Earlier research has focused primarily on the extrinsic effects of servant leadership on employee behavior, often overlooking its intrinsic influences, such as relational identification and POS (Zou et al., 2017). Although studies have focused on how leadership behavior fosters a positive relationship with employees’ OCB, such studies frequently fail to discuss the potential influence of employees’ negative emotions on this relationship. Negative emotions, such as workplace loneliness, have been shown to undermine employees’ OCB (Lam and Lau, 2012). When employees experience negative emotions, they may lack interest in servant behavior, which can reduce their receptiveness to such behavior and make it difficult for servant leadership to effectively motivate subordinates (Wu et al., 2021). Therefore, further attention must be given to employees’ negative emotions. This paper provides an introductory explanation of workplace loneliness and explores how it moderates the impact of servant leadership on employees’ OCB.

Theoretical foundation

Social exchange theory (SET), social identity theory (SIT), and psychological contract theory (PCT) can provide a foundational framework for understanding the complex interactions among servant leadership (SL), relational identification, POS, OCB, and workplace loneliness. Here, this framework is used to examine the mediating roles of relational identification and POS and to investigate how workplace loneliness negatively moderates the sequence mediating effect of SL on OCB.

SET proposes that social interactions are driven by a process of exchange to gain the most benefits while reducing costs (Blau, 1964), placing significant emphasis on the idea of mutual exchange or mutual benefit (Gouldner, 1960). According to SET, the provider of benefits to others expects reciprocation. Recipients of these benefits, in turn, feel obliged to take specific actions in return (Homans, 1958). When leaders make the well-being of employees a top priority, demonstrate genuine care, and actively listen to and address employees’ interests and needs, employees feel appreciated and valued by their leaders (Gotsis and Grimani, 2016). Therefore, employees are more inclined to take proactive action as a form of reciprocity with their leaders. This theory elucidates the relationship between SL and OCB by explaining how leaders’ supportive behaviors can foster reciprocal positive behaviors from employees, such as increased OCB. Additionally, SET explains the mediating role of POS, highlighting how POS can enhance employees’ motivation to reciprocate through OCB (Eisenberger et al., 1986).

SIT explores how people form their identity and self-worth on the basis of their belonging to social groups (Tajfel and Turner, 1986). It emphasizes that people tend to identify with and attach significance to the groups to which they belong. This identification can influence self-concept and self-esteem, as an individual derives a sense of belonging from their group membership (Tajfel and Turner, 1986). SIT is crucial for explaining the mediating role of relational identification in the relationship between SL and OCB, as servant leaders prioritize employees’ development and support (Liden et al., 2014), and their behaviors align with employees’ role expectations (Sluss and Ashforth, 2007), resulting in increased identification with the leaders (Johnson et al., 2010; Zou et al., 2017).

PCT involves unwritten and implicit expectations between employees and employers (Rousseau, 1989). PCT assumes that the payment and benefit harvest of employees and enterprises must be equal and fair, forming an equal relationship between responsibilities and obligations (Zhou, 2020). This kind of reciprocal relationship of responsibility and obligation is conducive to maintaining the stability of the relationship between enterprises and employees. However, when one party thinks that the return he or she receives does not compensate for his or her own efforts, the stability of this relationship will be damaged, causing a negative perception of the other party; thus, the relationship between the two is likely to break down (Li, 2020). Wright (2005) reported that feeling lonely in the workplace can cause employees to lack identification with organizational membership. In this case, employees evaluate the working environment negatively and express concerns about relationships with others in the workplace (Wei et al., 2019). Employees experiencing loneliness in the workplace may be reluctant to actively communicate with leaders (Zhu, 2017) and harbor feelings of distrust of or dissatisfaction with their leaders (Dai, 2021). Despite leaders’ efforts to provide support, employees may struggle to form meaningful relationships with them due to their sense of loneliness (Liu et al., 2016; Wei et al., 2019; Zheng et al., 2022). This challenge weakens the effectiveness of the psychological contract. This theory is particularly relevant for understanding the moderating effect of workplace loneliness, as breaches in psychological contracts can lead to feelings of isolation and disengagement, negatively impacting OCB (Morrison and Robinson, 1997).

To address the existing research gaps, the current study seeks to achieve several objectives: (1) to examine how relational identification plays a mediating role in connecting SL with OCB; (2) to assess how POS plays a mediating role in connecting SL with OCB; (3) to investigate how servant leadership influences OCB through the sequential mediation of relational identification and POS; and (4) to examine how workplace loneliness moderates these mediated relationships, particularly between SL and OCB.

By addressing these objectives, this study makes several key contributions: (1) it enriches the current understanding in the area by focusing on the intrinsic influences of servant leadership, going beyond the usually studied extrinsic factors; (2) by integrating employees’ negative emotion, such as workplace loneliness, as a moderator, the study offers a fuller, more nuanced view that is not purely leader-centric, illuminating why the beneficial outcome of servant leadership occasionally appears to be weakened; (3) the study advances the literature by using SET, SIT, and PCT to provide a robust theoretical grounding for the observed relationships and; (4) finally, by focusing on the unique context of Chinese private enterprises, the study is particularly relevant to practitioners and policy-makers concerned with improving organizational performance in emerging economies.

Thus, this study aspires to extend the theoretical boundaries of the field and offer practical insights into the role and impact of SL on OCB, particularly in China’s rapidly evolving private sector.

Literature review and hypothesis development

Servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior

“OCB” refers to the voluntary actions of employees that are not required by their job but contribute to overall well-being in the workplace. These are helpful activities that are not officially rewarded but that collectively improve a company’s operations (Organ, 1988). OCB reflects an employee’s willingness to exceed their job responsibilities for the organization’s benefit. Earlier research highlights a clear link: when leaders serve their teams and put them first, such as occurs in servant leadership, there is a noticeable increase in these extra efforts by employees (Newman et al., 2017; Neubert et al., 2016).

First, the essence of SL reflects the fundamental principles of “service” and “altruism” (Greenleaf, 1977). SL involves prioritizing followers’ needs. By consistently offering help and support, servant leaders make employees feel valued both by the leaders themselves and their organizations (Newman et al., 2017; Zou et al., 2020); subsequently, employees have a high level of satisfaction with and recognition of the leader and organization (Zou et al., 2020). Therefore, while performing their duties well, employees are willing to go beyond the prescribed job responsibilities to participate in actions that benefit the organization, and they are likely to exert extra effort to repay the care and assistance they receive from their leaders and the organization (Anand et al., 2018; Zou et al., 2017). In addition, the selfless and continuous service behaviors of leaders subtly influence employees, creating an atmosphere of dedication and selfless service within the organization (Liu, 2011). Consequently, under the influence of leaders’ sincere attitude towards employees, even if this attitude is not mandated by the organization, employees are motivated to put in more effort into their work and willingly go beyond their assigned responsibilities to contribute positively to the organization (Anand et al., 2018; Zou et al., 2017).

Moreover, SL encompasses nurturing employee well-being by advocating for their growth, and providing the support employees need to overcome work-related challenges. Appreciative of the support and resources offered by such leaders, employees reciprocate with actions that, while beyond their official duties, enhance organizational performance. This give-and-take dynamic aligns with social exchange theory, embodying the reciprocity principle (Zou et al., 2017). We anticipate a positive association between SL and OCB. Hence, we suggest the following hypothesis:

H1: Servant leadership is positively related to OCB.

Mediating effect of relational identification

Relational identification is considered a way individuals may define themselves through the significant roles they play within relationships (Sluss and Ashforth, 2008). This concept relies on the interplay between individuals within any given relationship and how they perceive their respective person-based and role-based identities (Sluss and Ashforth, 2008). Leadership style is a powerful determinant in guiding employee behavior, often dictating a certain path or approach for employees to follow (Guo, 2020). The manner in which employees engage with their organization can be instrumental in shaping their sense of self and, consequently, can lead to changes in how they act in the workplace (De Cremer and Van Knippenberg, 2005). While much research has focused on how individuals identify with their organization as a whole unit, the concept of relational identification at an individual level has not received as much scholarly focus (Guo, 2020).

In practice, interpersonal relationships are founded on work undertaken directly with employees. Positive interactions between employees and leaders play a crucial role in establishing stable and enduring role relationships (Sluss and Ashforth, 2008). Additionally, these interactions foster favorable views of leadership and further improve employee-leader relational identification (Ma and Liu, 2020). Relational identification focuses on interpersonal-level identification (Sluss and Ashforth, 2007). In this study, “relational identification” refers to relationships between employees and leaders and reflects the employees’ dependence on and identification with leaders (Sluss and Ashforth, 2007).

SL concerns being employee-centered, committed to providing services, and caring for and helping employees grow and develop (Vinod and Sudhakar, 2011). When servant behaviors occur, employees interpret such behavior as indicating leaders’ recognition, care, and support, and servant leaders gain respect and trust from employees, which builds strong relationships. Consequently, this improves employee-servant leader relational identification (Sluss et al., 2012; Yoshida et al., 2014). Employees not only shape their own behaviors and ideas according to those of a servant leader but also define themselves according to their relationships with leaders as a means of improving relational identification (Sluss et al., 2012; Zou et al., 2017). Leaders who practice servant leadership connect with each team member and recognize their needs, resulting in a strong binary relationship that then motivates the leader’s followers to reciprocate with OCB (Ruiz-Palomino et al., 2023).

To summarize, servant leadership places the employee at the forefront, giving priority to their growth, development, and well-being. Servant leaders are proactive in offering their services, support, and assistance to employees (Liden et al., 2014). They also exemplify the use of listening skills and empathy in workplace interactions (Zou et al., 2017). By fostering high-quality interpersonal relationships, SL enables employees to clearly perceive the value and importance of their role relationships, leading to a stronger alignment of their personal ambitions with their work roles, thus intensifying their sense of relational identification (Liden et al., 2014; Qu et al., 2015). Grounded in SIT, a robust sense of relational identification among employees often results in alignment with the leader’s vision (Sluss and Ashforth, 2007), driving behaviors that align with the employees’ identity objectives (Van Knippenberg (2000)). This stronger identification prompts such so-called followers to adopt the leader’s aims as their personal aims (Guo and Xiao, 2016), thus increasing their propensity to exhibit positive, role-exceeding behaviors. Consequently, employees are inclined not only to satisfy their explicit job requirements but also to voluntarily partake in additional actions that benefit the leader and the broader organization. Therefore, we suggest a hypothesis as follows:

H2: relational identification significantly mediates the relationship between SL and OCB.

Mediating role of perceived organizational support

POS is considered an employee’s view of the “extent to which their organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being” (Eisenberger et al., 1986. p. 501). Research shows that employees with higher levels of POS exhibit greater willingness to make efforts to reciprocate with leaders and organizations (Chen and Ge, 2020). Consequently, this approach leads to increased recognition, motivating employees to demonstrate greater concern for the organization and display more beneficial behaviors (Bowler and Brass, 2006). When employees perceive support from the organization, their trust in the organization increases, as they believe that the organization will offer fair feedback and appropriate compensation for their extra-role behaviors (Rockstuhl et al., 2020).

In the organizational context, leaders can be seen as embodiments of the organization itself, and the way they treat employees is interpreted as reflective of the organization’s attitudes. Support from leaders, therefore, is perceived as an extension of organizational support, offering employees a greater pool of resources and support in the workplace (Demerouti et al., 2001). As employees gain these resources, their motivation and initiative at work tend to increase (Zacher et al., 2019). Through SET, the support that employees perceive from their leaders and organizations cultivates a culture of reciprocity. This encourages them to contribute more significantly to the organization, often by engaging in extra-role activities as a form of repayment, which is indicative of increased OCB (Thompson et al., 2020). In response to this literature, we posit the following hypothesis:

H3: the relationship between SL and OCB is mediated by POS.

Sequential mediating effect of relational identification and POS

Few studies have examined the effect of relational identification (Huang et al., 2016). Sluss and Ashforth (2007) and Carmeli et al. (2009) have explored relational identification in organizational contexts, but comprehensive studies that integrate this construct with perceived organizational support (POS) are scarce.

To substantiate this impression, we conducted a literature search using “relational identification” and “perceived organizational support” as keywords or topics in databases such as Scopus, Web of Science, CNKI, and Emerald. The search results indicated that there is indeed limited research on the sequential mediating effect of relational identification and POS. For instance, while certain studies, such as Ashforth, Harrison, and Corley (2008), discuss relational identification broadly, they rarely connect this concept directly with POS in a sequential mediation framework. Similarly, Rhoades and Eisenberger (2002) focus extensively on POS but do not delve into its interaction with relational identification in a sequential manner.

However, other research alludes to a possible relationship between these two concepts. One group of researchers indicates that relational identification has a positive influence on employees’ personal relationships with leaders, along with their perceptions of leaders’ charisma (Steffens et al., 2014). Greater relational identification with leaders leads to better personal relationships and improved perceptions of leadership charisma (White et al., 2021). Employees’ perceptions of leadership support can be significantly influenced by the strength of the bonding relationship between employees and their leaders (Kim et al., 2021). Furthermore, the perception of support from leaders leads to POS (Rhoades and Eisenberger, 2002), which largely relies on employees’ identification with leaders (Eisenberger et al., 2002). In light of this logic, the degree of relational identification plays a pivotal role in shaping employees’ perceptions of leader support, as leaders are seen as agents of organizations, subsequently affecting POS.

In the context of SL, with its focus on serving and supporting employees, actions by leaders that demonstrate care, empathy, and healing are viewed by employees as acknowledgments of their value and support, hence reinforcing their identification with the leader (Liden et al., 2014). As employees’ identification with the relationship with their leaders intensifies, they are more likely to resonate with their leaders (Sluss and Ashforth, 2007; Zheng et al., 2022), thus placing greater emphasis on nurturing this relationship while interpreting leaders’ supportive actions as direct recognition and an indication of a valued bond. Leaders, as representatives of the organization (Rhoades and Eisenberger, 2002), can endow employees with a heightened sense of organizational support as this identification strengthens (Kim et al., 2021). Understood through this lens, employees perceive the supportive gestures of their leaders not only as personal backing but also as endorsements from the organization itself (Eisenberger et al., 2020). To draw on social exchange theory, such perceptions incite employees to reciprocate with commitment and discretionary efforts and be willing to undertake additional tasks as a sign of gratitude, thereby increasing OCB (Farh et al., 2007). This rationale leads us to posit the hypothesis as follows:

H4: the influence of SL on OCB is sequentially mediated by relational identification followed by POS.

Moderating effect of workplace loneliness

From an evolutionary perspective, loneliness is an unpleasant experience that also makes individuals feel unsafe in their environment, leading to negative emotions (Cacioppo et al., 2014). Workplace loneliness, defined as the distressing experience resulting from perceived deficiencies in one’s social relationships at work, can significantly affect employees’ behaviors and attitudes (Wright, 2005). Wright (2005) conceptualized workplace loneliness as encompassing both “emotional deprivation” and “social companionship deficiencies”. The negative impact of workplace loneliness on OCB is well documented, as employees experiencing loneliness often feel disconnected from their colleagues and their organization, leading to reduced engagement in discretionary behaviors that benefit the organization (Lam and Lau, 2012).

Workplace loneliness has a negative effect on organizational commitment, job engagement, innovation behavior, and emotional exhaustion (Xu et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019; Ayazlar and Güzel, 2014; Peng et al., 2017; Anand and Mishra, 2021) and a positive effect on turnover intention and counterproductive behavior (Chen et al., 2021; Promsri, 2018). Employees who feel lonely in the workplace are less likely to engage in OCB because of their perceived lack of support and recognition from the organization and their peers (Ozcelik and Barsade, 2018).

On the basis of SET, individuals seek to establish stable trust relationships with others to achieve long-term reciprocity (Blau, 1964). When an organization fulfils employees’ desires for close relationships and social interactions, employees perform their job well and make extra efforts to achieve organizational goals. Owing to their negative self-perception and lack of trust in others, lonely employees are unwilling to take the risk of social exchange with the organization; this perception can undermine their motivation to exceed their official job duties to help colleagues or contribute to organizational goals, thus reducing their altruistic behaviors within the organization (Lam and Lau, 2012; Li and Ye, 2015).

Wright (2005) contended that employees who feel lonely in the workplace experience a lack of identification with organizational membership. People who feel very lonely often have more problems with social interaction (Qu et al., 2010). When employees perceive that their social needs are not satisfied by their colleagues and organizations, they may experience workplace loneliness, which is apathy in a psychological sense (Ozcelik and Barsade, 2018). Workplace loneliness includes “emotional deprivation” and “a lack of social companionship”, with emotional deprivation specifically related to employees’ interpersonal relationships in the workplace (Ayazlar and Güzel, 2014). In such circumstances, employees may perceive the working environment negatively and express concerns about their relationships with others in the workplace (Wei et al., 2019). Thus, employees who feel isolated may struggle to form meaningful relationships with their leaders and colleagues, leading to a decrease in relational identification (Wei et al., 2019) and weakening the mediating pathways through which servant leadership influences OCB. A lack of social interaction and support can lead to negative self-perceptions and lower self-esteem, further exacerbating feelings of loneliness and reducing the likelihood of exhibiting OCB.

Individuals in organizations strive to develop stable and trusting relationships with others, aiming for long-term mutual benefits. When organizations fulfill employees’ desire for meaningful relationships, not only do the employees excel in their job performance, but they also exert additional effort to achieve organizational goals (Wang, 2022b). However, the greater the level of workplace loneliness employees experience, the more difficult it is for them to establish high-quality relationships with their leaders (Liu et al., 2016; Wei et al., 2019; Zheng et al., 2022). This occurs because of a negative view of oneself and difficulty connecting with one’s own identity (Wright, 2005). Consequently, this causes difficulty in establishing strong relationships with leaders (Ozcelik and Barsade, 2011). Employees who feel very lonely often believe that they are not achieving what leaders expect from them (Zhu, 2017). This makes them reluctant to engage in active communication with leaders. This, in turn, creates a lack of trust or confidence in one’s interactions with leaders (Dai, 2021).

PCT addresses the unwritten expectations and informal relationships that are present between employees and leaders (Levinson et al., 1962; Rousseau, 1995). These expectations encompass not only tangible aspects, such as salary and benefits, but also psychological and social elements, such as the quality of relationships and the sense of belonging within the workplace (Rousseau, 1990, 1995). Workplace loneliness can disrupt beneficial aspects of the psychological contract, such as trust, support, and the sense of belonging (Raja et al., 2004; Deery et al., 2006). This breach in the psychological contract can, in turn, result in a lower level of relational identification, as employees may struggle to connect with their leaders, colleagues and the organization due to negative emotions, such as distrust, because they consider that their social and emotional needs are not being fulfilled (Raja et al., 2004; Wang and Yang, 2010). This perception can lead to decreased trust and a reduced willingness to engage in reciprocal behaviors, such as OCB.

On the basis of this logical reasoning, workplace loneliness makes employees feel isolated and disconnected, resulting in a lack of belonging (Li and Ye, 2015). This can hinder employees from establishing trust and aligning themselves with their leaders. Consequently, employees may refrain from seeking assistance or raising inquiries with their leaders, as they struggle to forge positive interactions and connections with them (Lam and Lau, 2012; Li and Ye, 2015). This impacts employees’ perceptions of their leaders (Steffens et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2021); thus, even if leaders exhibit servant behavior and attitudes, employees may fail to recognize or undervalue these efforts due to their experience of loneliness. Once employees perceive strong loneliness in the workplace, they will evaluate the surrounding environment and relationships in a negative way (Wei et al., 2019), their psychological resources will be continuously depleted, their psychological uncertainty will increase, and they will think that they are unwelcome, question their work ability, and even have negative self-cognition, making it difficult to establish contact with other members of the organization (Wei et al., 2019; Zheng et al., 2022). It is also difficult to establish relationships with leaders, further resulting in a lack of relational identification (Wei et al., 2019). Against this background, the moderation hypothesis is proposed.

The mediation hypothesis suggests that relational identification and POS act as a chain mediating effect between SL and employees’ OCB. The moderation hypothesis proposes that direct interaction between employees’ workplace loneliness and SL affects relational identification. On the basis of these hypotheses, we argue that workplace loneliness could significantly moderate the sequential mediating hypothesis. Combining the analysis provided above, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H5: the mediating impact of SL on OCB via relational identification and POS varies with employees’ level of workplace loneliness. Specifically, higher levels of workplace loneliness weaken the indirect effect of SL on OCB.

Proposed research framework

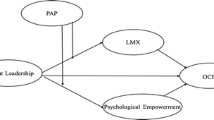

Building on the above discussion, we formulate the research framework (Fig. 1). By integrating three theories, namely, SET, SIT, and PCT, our study seeks to address the existing research gaps by investigating the mediating effect of relational identification and POS on the relationship between SL and OCB and additionally examining the moderating influence of workplace loneliness on the mediation of SL and OCB.

Methodology

Sample and procedure

The fieldwork of this study was performed in Zhejiang Province, China, which is known for having China’s highest concentration of private enterprises, contributing to a total economy exceeding 4 trillion yuan. It represents one of China’s leading provinces in terms of private enterprise development (He, 2022). In this cross-sectional study, a convenience sampling approach was employed to select both private enterprises and employees as participants (Etikan et al., 2016). The questionnaire underwent a pretest with three experts in the field and a pilot test involving 30 respondents to establish the adapted scale measurement’s reliability and validity. Subsequently, an email invitation was dispatched to 20 companies, seeking their assistance in distributing the questionnaire to employees who displayed interest in participating in the survey. Out of the 20 companies contacted, only seven consented, granting permission to administer the survey their employees. The email included a web link and a QR code facilitating access to the questionnaire. The email was accompanied by a cover letter assuring participants that all the responses would be kept confidential. The fieldwork was successfully concluded within a span of six weeks. A sample of 335 respondents participated in the survey, comprising 187 male respondents and 148 female respondents. The details of the demographic profile are presented in Table 1.

Measurements

The measurement scales were adopted from previous studies. Servant leadership was an independent variable. The measurement of servant leadership utilized the seven-item measurement scale by Liden et al. (2015). This version of the scale has been widely used in numerous studies (Chughtai, 2018; Eva et al., 2019; Lan et al., 2020; Liu, 2020). Sample items are “My leader can tell if something work-related is going wrong” and “my leader makes my career development a priority”. The reliability coefficient score for this scale was 0.893, indicating good reliability. The scale has been validated and used in various studies with high reliability scores, demonstrating its robustness and consistency (Chughtai, 2018; Eva et al., 2019; Lan et al., 2020; Liu, 2020).

Organizational citizenship behavior was the dependent variable. The Ahmad and Zafar (2018) five-item scale was used to measure OCB. This scale originated in research by Organ et al. (2006) and was subsequently validated by Ahmad and Zafar. Sample items are “I am willing to do more work than what the organization requires” and “I usually help other colleagues with their work”. The reliability coefficient score for this scale was 0.818, indicating good reliability.

A measurement scale by Sluss et al. (2012) with four items was adapted to assess relational identification. Sample items are “I would feel offended if someone criticized my relationship with my immediate supervisor” and “My relationship with my immediate supervisor is important to my self-image at work”. This four-item scale produced a reliability coefficient score of 0.809, indicating good reliability.

Perceived organizational support was assessed via a six-item measurement scale by Albalawi et al. (2019). These items were derived from pioneer researchers Eisenberger et al. (1990; 1997), who invented a POS scale. Example items are “I feel treated fairly in the organization” and “my organization cares about my general satisfaction”. This six-item scale achieved a Cronbach’s alpha score of 0.897, indicating good reliability.

Workplace loneliness was measured by Lam and Lau’s (2012) four-item instrument. This scale originated in Russell’s revised UCLA loneliness scale (1980), with all the items modified to be applicable to the work domain. For example, we initially changed the item “I can find companionship when I want it” to “I can find companionship in my workplace when I want it”. However, since this item was reversed-scored and could confuse participants, we ultimately revised it to “I lack companionship in my workplace when I want it”. Other sample items are “I am no longer close to anyone within this organization” and “I lack companionship in my workplace when I want it”. The reliability coefficient score for this scale was 0.939, indicating good reliability.

Data analysis and results

Initially, SPSS software was used to conduct descriptive analysis, assess normality, and perform common method bias analysis. Subsequently, Smart PLS software was utilized for model testing. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was used for data analysis in this study. PLS-SEM is a statistical technique that allows researchers to analyze complex relationships between observed and latent variables (Hair et al., 2021). PLS-SEM, a variance-based SEM approach, is used for causal predictive modeling to maximize the explained variance of dependent latent constructs (Chin et al., 2020; Shmueli et al., 2019; Hair et al., 2011). This method is useful in social sciences and business research, as it can handle small sample sizes, nonnormal data distributions, and complex models with multiple constructs and indicators (Hair et al., 2017).

PLS-SEM focuses on maximizing the explained variance of the dependent constructs, making it well suited for predictive analysis (Hair et al., 2019). It involves two main components: the measurement model (also known as the outer model), which assesses the relationships between indicators and their corresponding latent constructs, and the structural model (also known as the inner model), which evaluates the relationships between the latent constructs themselves (Henseler et al., 2015).

The analytical procedure involved the evaluation of the measurement model and structural path modeling. In stage one, we assessed the measurement model, which encompassed determining internal consistency reliability (composite reliability), indicator reliability, convergence validity (average variance extracted, AVE), and discriminant validity (Heterotrait-monotrait ratio, HTMT) (Henseler et al., 2015). In the subsequent stage, we evaluated the structural model to elucidate how each construct is represented by the corresponding manifest indicators.

Preliminary analysis

Table 2 depicts the means, standard deviations, kurtosis, skewness, and intercorrelations among the key constructs. The mean score for each construct exceeds the midpoint of 3.00, indicating that respondents generally perceive relatively high levels of servant leadership, organizational support, and workplace loneliness. Additionally, they exhibit a strong sense of relational identification and a greater tendency to practice citizenship behavior in the workplace. The standard deviation for each construct falls within an acceptable range, suggesting that the data points in the sample are relatively consistent and close to the mean (Jacobson and Truax, 1992).

With respect to data normality, both the skewness and kurtosis values for each construct fall within the acceptable ranges of −3 and +3 and −10 and +10, respectively (Brown, 2006), indicating a normal distribution. We acknowledge the critique by Fuller et al. (2016) regarding insufficiency in testing common method bias (CMB) due to the lack of statistical control for method effects. In response to this critique, we implemented the procedure suggested by Kock (2015), which proposes that if the variance inflation factors (VIF) for the inner model is 3.3 or less, the model is likely free from CMB. After a full collinearity assessment was performed, our findings indicated that all the VIFs were in fact below the threshold (Table 3). Therefore, we concluded that CMB does not pose a concern for our model on the basis of this more recent and robust statistical approach. As a result, this study does not raise significant concerns about common method bias.

For model fit, in line with the guidelines of Schumacker and Lomax (2010) and Hair et al. (2022) on reporting model fit for PLS-SEM, we evaluated the model’s fit by checking the values of approximate fit indices, such as SRMR and NFI, directly from the PLS-SEM model results. Specifically, when these indices were compared with established benchmarks, we found that SRMR was less than 0.08 (SRMR value = 0.066) and that NFI was greater than 0.80 (NFI value = 0.836). The NFI value ranged from 0 (no fit) to 1 (perfect fit), with a value close to 0.90 indicating good model fit. These criteria fall within the acceptable thresholds (e.g., SRMR < 0.08 and NFI > 0.80), indicating that the model has achieved a satisfactory model fit (Table 3). As a result, this study does not raise significant concerns about common method bias.

Assessment of the measurement model

Table 4 presents the outer loadings, composite reliability, and AVE scores for each construct. The composite reliability of all the constructs surpasses the minimum threshold of 0.708 (Hair et al., 2022), indicating the strong overall reliability of the model. With respect to outer loadings, none of the items fall below the acceptable threshold of 0.708 (Hair et al., 2022). Furthermore, the AVE score for each construct is greater than the threshold of 0.500 (Hair et al., 2022). Hence, we can conclude that the model’s convergent validity is firmly established.

HTMT was utilized to examine discriminant validity (Table 5). Clark and Watson (1995) and Henseler et al. (2015) have endorsed a stricter criterion, proposing that HTMT values should remain below 0.85. As shown in Table 3, all the items conform to these criteria. Consequently, the achievement of discriminant validity is confirmed.

Assessment of the structural model

PLS-SEM does not assume normally distributed data; therefore, it uses nonparametric bootstrapping, “which involves repeated random sampling with replacement from the original sample to create bootstrap samples and obtain standard errors for hypothesis testing” (Hair et al., 2011. p. 148). We utilized a bootstrapping procedure with 10000 bootstrap samples to examine the significance of the path coefficients (Hair et al., 2022). As shown in Table 6, the effect of servant leadership on OCB is positively significant (β = 0.296, t = 5.725, p < 0.01), supporting Hypothesis 1. The effect of SL on OCB is significantly mediated by relational identification (β = 0.146, t = 4.445, p < 0.01) and perceived organizational support (β = 0.105, t = 3.258, p < 0.01). Therefore, Hypotheses 2 and 3 are supported. Since both the direct path and the indirect path are statistically significant, both mediating paths are considered partial mediation effects.

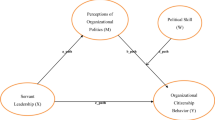

In addition, we also found that the sequential mediation between servant leadership and OCB was statistically significant (β = 0.045, t = 2.812, p < 0.01). Hence, Hypothesis 4 is well supported. Finally, the workplace loneliness functioned as a significant moderator of the effect of servant leadership on relational identification (β = −0.025, t = 2.206, p < 0.05). Therefore, H5 is supported. Figure 2 presents a moderation analysis, where workplace loneliness moderates the relationship between SL and relational identification. The graph has three lines, each representing different levels of workplace loneliness: low (1 SD below the mean), average (the mean), and high (1SD above the mean). The graph indicates that the positive impact of SL on relational identification is more pronounced when workplace loneliness is low (red line). Here, as SL increases, there is a steeper inclination in relational identification, suggesting that employees who feel less lonely in the workplace are more responsive to the effects of servant leadership.

In contrast, for employees who experience average workplace loneliness (blue line), the positive relationship between SL and relational identification remains, but the slope is less steep compared to the low loneliness scenario. This implies a moderate level of responsiveness to servant leadership. Finally, the green line indicates that when workplace loneliness is high, the positive slope is the flattest among the three scenarios. This suggests that the influence of SL on relational identification is dampened when employees feel more isolated or disconnected at work.

Overall, the graph illustrates that while SL has a positive effect on relational identification across different levels of workplace loneliness, the strength of this effect is contingent upon the degree of loneliness employees experience, with less loneliness amplifying the impact of SL.

In summary, H1, H2, H3, H4, and H5 are all supported (Table 6).

Discussion

The results of our investigation demonstrate the substantial roles that servant leadership, relational identification, and POS play in enhancing employee engagement in OCB. This discussion enriches each hypothesized link in our study, and explores the practical implications of our findings.

First, confirming our hypothesis, we identified a positive relationship between SL and OCB; enhanced servant leadership practices are associated with a corresponding increase in the occurrence of OCB. This outcome aligns with previous studies, demonstrating the consistency of these findings and their significance in real-world applications (Reed, 2016; Newman et al., 2017; Zou et al., 2020). This outcome also suggests that when leaders engage in servant leadership behaviors, employees are more likely to reciprocate with OCB. Here, the practical implication is that organizations should invest in training programs that cultivate servant leadership qualities in their leaders.

Second, the role of relational identification as a mediator between SL and OCB is pivotal. When a servant leader demonstrates care, support, empathy, healing, and other helpful behaviors, employees perceive these actions as indicators of a strong, high-quality relationship with the leader, fostering a sense of relational identification (Sluss et al., 2012; Yoshida et al., 2014). This strengthened identification between employees and leaders translates into increased employees’ willingness to engage in behaviors that extend beyond their job duties as a way of reciprocating the leader’s support. Thus, when leaders cultivate strong, supportive relationships, they enhance employees’ relational identification, which strengthens their tendency to exhibit OCB. This finding aligns with previous research (Zou et al., 2017). The implications for leadership are clear: leaders should focus on cultivating genuine, supportive relationships with their followers to foster a workplace culture where exceeding job expectations becomes the norm.

Third, the significant mediating effect of POS on the relationship between SL and OCB shows that employees view servant leadership actions as a representation of the organization’s support, which in turn encourages OCB. Employees interpret leaders’ support as an extension of the organization’s support, which then triggers reciprocal behaviors on the basis of social exchange theory, leading to greater engagement in OCB as a way of giving back to both their leaders and the organization. This finding is consistent with those of previous studies (Hakanen et al., 2011; Thompson et al., 2020). Additionally, it highlights the need for organizations to communicate support not only at the interpersonal level but also across the entire system, fostering a culture of mutual support and active contribution.

Fourth, our study reveals the sequential mediation of both relational identification and POS in the relationship between SL and OCB. This sequential mediation effect has rarely been observed in previous research (Eva et al., 2019; Lu et al., 2022). Most studies typically combine relational identification and organizational identification (Zou et al., 2017), with few studies linking relational identification to POS. Through their altruism and selflessness, servant leaders nurture a strong sense of identification in employees, not only with leaders but also with respect to the relationship between them (Liden et al., 2014; Newman et al., 2017). As leaders represent the organization (Chen et al., 2002), this identification naturally extends to the organization itself, leading employees to perceive higher levels of organizational support. This perceived support fosters shared beliefs and encourages positive OCB (Farh et al., 2007). This intricate dynamic suggests that servant leadership qualities, such as altruism, can enhance employees’ identification with their leaders and the organization, thereby promoting a culture of OCB. This finding has practical implications for organizational training and culture development, indicating that fostering a strong sense of community and support can improve overall organizational performance.

Finally, we address the role of workplace loneliness as a negative moderator between SL and relational identification. Previous research has reported how servant leadership can reduce workplace loneliness (Lin, 2019; Jin and Ikeda, 2023). In contrast, our study reveals that workplace loneliness, as a negative emotion, can diminish the benefits of servant leadership. This finding suggests that employees’ emotional states can significantly impact their behavior. While workplace loneliness may be an overlooked emotional state, its effect on employees’ performance is noteworthy and considerable. When employees experience pronounced loneliness at work, their responsiveness to servant leadership decreases, weakening their identification with leaders and consequently reducing their engagement in OCB (Wei et al., 2019). Therefore, organizations should implement proactive strategies to address workplace loneliness. Leaders and organizations need to prioritize employees’ emotional well-being and offer necessary support and resources to help them build closer social networks. Activities such as team-building activities and open communication channels can prevent the negative effect of workplace loneliness and ensure that the benefits of servant leadership are fully realized.

In summary, these findings not only reaffirm the theoretical constructs of our research framework but also provide actionable insights for organizations seeking to foster a culture of citizenship and engagement. They emphasize the significant impact of leadership styles and the perceived work environment on employee behaviors.

Theoretical and managerial implications

The theoretical implications of this research lie in enriching the body of knowledge regarding the mediating effect that links SL with OCB. This study increases our insight into the complex mechanisms through which SL influences OCB through moderated mediation.

The research presented here goes beyond investigating the sequential mediating effect between SL and OCB by introducing workplace loneliness as a moderator. This is a novel approach, as prior research has predominantly concentrated on factors that bolster the positive impacts of OCB (Li, 2022). The identification and examination of workplace loneliness as a moderating factor address a gap in the literature, which often overlooks the potential detrimental impacts of negative emotional states on the SL-OCB nexus. In this way, the study underlines the importance of not neglecting employees’ adverse emotional experiences.

From a managerial perspective, organizations should prioritize the cultivation of leadership styles, nurturing more servant leaders, and promoting OCB by focusing on employees’ needs and relationships. These goals can be accomplished by targeted training and development programs and by demonstrating good servant leadership behaviors. Relational identification significantly affects the relationship between servant leadership and employees’ OCB. Therefore, it is essential for leaders practising servant leadership to actively work to strengthen employees’ relational identification with them. This entails fostering strong interpersonal connections, realizing emotional interaction between leaders and employees and promoting a supportive leadership climate conducive to enhancing employees’ engagement in OCB.

Organizations should also aim to promote a positive work environment and a strong organizational culture. These goals can be achieved by implementing measures such as offering favorable working conditions, establishing open and transparent communication channels, encouraging employee participation in decision-making, and providing ample development opportunities and reward systems. These initiatives and efforts aim to enhance employees’ relational identification and POS. Furthermore, leaders must be aware that workplace loneliness can undermine the positive impact of SL. It is vital for leaders to identify and mitigate feelings of workplace loneliness, especially when interacting with employees who are experiencing high levels of such loneliness. Leaders might consider improving reward systems, granting greater autonomy at work, and adjusting workloads to mitigate feelings of loneliness among employees.

Leaders and organizations should aim to cultivate a supportive and closely connected work environment by fostering cooperation and mutual support among employees. They can achieve this by implementing social support systems to help employees cope with feelings of workplace loneliness. Providing opportunities for employees to connect more closely with one another, such as social activities, team-building activities, and employee support groups, can help strengthen connections and support networks within the organization. In addition, leaders and organizations can provide emotional support and mental health resources to aid employees to deal with the negative effects of workplace loneliness. Such support and resources could include providing access to psychological counseling services, conducting mental health training sessions, and supporting employees in self-management practices. Addressing the root causes of loneliness in the workplace is also crucial for effectively combating this issue.

Limitations and recommendations

This study focuses on the interpersonal aspect of relational identification at the individual level. However, within organizations, multiple identifications exist, such as organizational identification and leader identification. This study does not examine these other forms of identification, and subsequent research should consider investigating them as crucial variables in this field of study.

The sample size in this study is limited and does not cover all regions of China. In future research, expanding the scope and number of selected samples is essential to increase the representativeness of the findings. While this study employs well-established measurement scales, future research should explore measurement methods that are specifically tailored to the Chinese context to further investigate SL.

This study adopts a cross-sectional approach. However, future studies could benefit from adopting a longitudinal approach. Longitudinal studies involve gathering data from the same participants (individuals, groups, or entities) on multiple occasions over a prolonged period. This method enables researchers to track how variables evolve over time and examine relationships between variables across different time points. By tracking these changes, researchers can infer the directionality of relationships and explore potential causal pathways.

Moreover, this study did not incorporate contextual factors, such as organizational culture, industry type, or geographical location. In future research, it is important to consider and integrate such factors into the study framework to facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of the topic. For example, by accounting for such factors, we could obtain a more profound understanding of the effectiveness of servant leadership practices and identify patterns in how employees perceive servant leadership and engage in OCB across diverse contexts. Ultimately, this holistic approach would provide valuable insights for both practical application and theoretical advancement. Additionally, future studies could benefit from adopting qualitative research, which could provide increased insight into the factors that might affect SL and offer a richer understanding of workplace dynamics.

Conclusion

This research proposes a model of the sequential mediating effect, offering a fresh perspective on the relationship between SL and OCB. Our findings indicate that SL can positively influence OCB through the sequential mediating pathways of relational identification and POS. However, employees’ experience of workplace loneliness may diminish this impact. This study uncovers how servant leadership shapes OCB, emphasizing the crucial mediating roles of relational identification and POS. Additionally, it explores potential explanations for why servant leadership might not consistently enhance OCB among all employees. For example, negative emotions could be one such factor. Future research could further investigate these potential reasons, enabling servant leaders to adapt their behavior and mitigate any detrimental effects on the positive impact of SL.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study is available within the supplementary information files.

References

Aboramadan M, Hamid Z, Kundi YM, El Hamalawi E (2022) The effect of servant leadership on employees’ extra‐role behaviors in NPOs: The role of work engagement. Nonprofit Manag Leadersh 33(1):109–129. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21505

Ahmad I, Zafar MA (2018) Impact of psychological contract fulfillment on organizational citizenship behavior: Mediating role of perceived organizational support. Int J Contemp Hospitality Manag 30(2):1001–1015. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-12-2016-0659

Anand S, Vidyarthi P, Rolnicki S (2018) Leader-member exchange and organizational citizenship behaviors: Contextual effects of leader power distance and group task interdependence. Leadersh Quar. 29(4):489–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.11.002

Albalawi AS, Naughton S, Elayan MB, Sleimi MT (2019) Perceived organizational support, alternative job opportunity, organizational commitment, job satisfaction and turnover intention: amoderated-mediated model. Organizacija 52(4):310–324. https://doi.org/10.2478/orga-2019-0019

Anand P, Mishra SK (2021) Linking core self-evaluation and emotional exhaustion with workplace loneliness: Does high LMX make the consequence worse? Int J Hum Resour Manag 32(10):2124–2149. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1570308

Ashforth BE, Harrison SH, Corley KG (2008) Identification in organizations: an examination of four fundamental questions. J Manag 34(3):325–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308316059

Ayazlar G, Güzel B (2014) The effect of loneliness in the workplace on organizational commitment. Procedia-Soc Behav Sci 131:319–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.04.124

Blau PM (1964) Exchange and power in social life. Wiley

Bowler WM, Brass DJ (2006) Relational correlates of interpersonal citizenship behavior: a social network perspective. J Appl Psychol 91(1):70–82. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.1.70

Brown TA (2006) Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford Press

Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S, Boomsma DI (2014) Evolutionary mechanisms for loneliness. Cogn Emot 28(1):3–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2013.837379

Carmeli A, Gilat G, Weisberg J (2009) Perceived external prestige, organizational identification and affective commitment: a stakeholder approach. Corp Reput Rev 12(3):214–231. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr.1550014

Clark LA, Watson D (1995) Constructing validity: basic issues in objective scale development. Psychol Assess 7(3):309–319. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.309

Chen Y (2020) The challenges of private enterprises in China: a case study. J Chin Econ Bus Stud 18(3):255–270

Chen X, Peng J, Lei X, Zou Y (2021) Leave or stay with a lonely leader? An investigation into whether, why, and when leader workplace loneliness increases team turnover intentions. Asian Bus Manag 20(2):280–303. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41291-019-00082-2

Chen X, Ge Y (2020) Influence of family-work conflict on career growth of female employees: a regulated mediation model. Chin Pers Sci 3:31–41

Chen ZX, Tsui AS, Farh JL (2002) Loyalty to supervisor vs. organizational commitment: relationships to employee performance in China. J Occup Organ Psychol 75(3):339–356. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317902320369749

Chin W, Cheah JH, Liu Y, Ting H, Lim XJ, Cham TH (2020) Demystifying the role of causal-predictive modeling using partial least squares structural equation modeling in information systems research. Ind Manag Data Syst 120(12):2161–2209. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-10-2019-0529

Choong YO, Ng LP (2022) The effects of trust on efficacy among teachers: The role of organizational citizenship behaviour as a mediator. Curr Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03067-1

Chughtai AA (2018) Examining the effects of servant leadership on life satisfaction. Appl Res Qual Life 13(4):873–889. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-017-9564-1

Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli WB (2001) The job demands-resources model of burnout. J Appl Psychol 86(3):499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

De Cremer D, Van Knippenberg D (2005) Cooperation as a function of leader self‐sacrifice, trust, and identification. Leadersh Organ Dev J 26(5):355–369. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730510607853

Deery SJ, Iverson RD, Walsh JT (2006) Toward a better understanding of psychological contract breach: a study of customer service employees. J Appl Psychol 91(1):166–175. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.1.166

Dai Y (2021) The effect of workplace loneliness on employees’ emotional labor: the moderating effect of job embeddedness. Dissertation, Beijing Jiaotong University

Eisenberger R, Cummings J, Armeli S, Lynch P (1997) Perceived organizational support, discretionary treatment, and job satisfaction. J Appl Psychol 82(5):812–820. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.82.5.812

Eisenberger R, Fasolo P, Davis-LaMastro V (1990) Perceived organizational support and employee diligence, commitment, and innovation. J Appl Psychol 75(1):51–59. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.75.1.51

Eisenberger R, Huntington R, Hutchison S, Sowa D (1986) Perceived organizational support. J Appl Psychol 71(3):500–507. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500

Eisenberger R, Rhoades Shanock L, Wen X (2020) Perceived organizational support: why caring about employees counts. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav 7:101–124. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012119-044917

Eisenberger R, Stinglhamber F, Vandenberghe C, Sucharski IL, Rhoades L (2002) Perceived supervisor support: contributions to perceived organizational support and employee retention. J Appl Psychol 87(3):565–573. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.565

Etikan I, Musa SA, Alkassim RS (2016) Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am J Theor Appl Stat 5(1):1–4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

Eva N, Robin M, Sendjaya S, van Dierendonck D, Liden RC (2019) Servant leadership: a systematic review and call for future research. Leadersh Q 30(1):111–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.07.004

Fan JL, Zheng BS (2000) Paternalistic leadership in Chinese organizations: an analysis from a cultural perspective. Indig Psychol Res Chin Soc 01:6–11

Farh JL, Hackett RD, Liang J (2007) Individual-level cultural values as moderators of perceived organizational support–employee outcome relationships in China: Comparing the effects of power distance and traditionality. Acad Manag J 50(3):715–729. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.25530866

Fuller CM, Simmering MJ, Atinc G, Atinc Y, Babin BJ (2016) Common methods variance detection in business research. J Bus Res 69(8):3192–3198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.008

Gotsis G, Grimani K (2016) The role of servant leadership in fostering inclusive organizations. J Manag Dev 35(8):985–1010. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-07-2015-0095

Gouldner AW (1960) The norm of reciprocity: a preliminary statement. Am Soc Rev 25(2):161–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092623

Greenleaf RK (1977) Servant leadership: A journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness. Paulist Press, New York

Guo SH, Xiao MZ (2016) Collectivism-oriented human resource management and employees’ positive and negative reciprocity: the differently mediating role of organizational and relational identifications. J Bus Econ 12(302):29–36

Guo SH (2020) The influence of self-sacrificing leadership on employees’ voice behavior: the mediation of relational identity and the moderation of error management culture. Forecasting 39(5):61–67. https://doi.org/10.11847/fj.39.5.61

Hakanen JJ, Peeters MC, Perhoniemi R (2011) Enrichment processes and gain spirals at work and at home: A 3‐year cross‐lagged panel study. J Occup Organisational Psychol 84(1):8–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.2010.02014.x

He X (2022) The total amount exceeds 4 trillion, why is Zhejiang private economy so strong. ZJU News. http://zdpx.zju.edu.cn/news1_9320_305.html

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2015) A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Mark Sci 43(1):115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hair JFJr, Matthews LM, Matthews RL, Sarstedt M(2017) PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: updated guidelines on which method to use Int J Multivar Data Anal 1(2):107–123. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMDA.2017.087624

Hair JF Jr, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2022) A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). (3rd Ed.). Sage, Thousand Oakes, CA

Hair JF Jr, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M, Danks NP, Ray S (2021) An Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling. In: Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R. Classroom Companion: Business. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7_1

Hair JF Jr, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M(2011) PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet J Mark theory Pract 19(2):139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

Hair JF Jr, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM (2019) When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur Bus Rev 31(1):2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Homans GC (1958) Social behavior as exchange. Am J Sociol 63(6):597–606. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2772990

Huang YL, Liu SL, Liu XL (2016) Study on progress and prospect of relational identification. Soft Sci 31(1):95–100. https://doi.org/10.13956/j.ss.1001-8409.2017.01.21

Huang YZ (2013) The influence of authentic leadership on organizational citizenship behavior of employees: the mediating role of psychological capital. Dissertation, Central South University

Jacobson NS, Truax P (1992) Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. In A. E. Kazdin (ed.), Methodological issues & strategies in clinical research (pp. 631–648). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10109-042

Jin J, Ikeda H (2023) The role of empathic communication in the relationship between servant leadership and workplace loneliness: a serial mediation model. Behav Sci 14(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010004

Johnson RE, Chang CH, Rosen CC (2010) Who i am depends on how fairly i’m treated”: effects of justice on self‐identity and regulatory focus. J Appl Soc Psychol 40(12):3020–3058. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00691.x

Kim TW, You YY, Hong JW (2021) A study on the relationship among servant leadership, authentic leadership, perceived organizational support (POS), and agile culture using PLS-SEM: mediating effect of POS. Ilkogr Online 20(3):784–795. https://doi.org/10.17051/ilkonline.2021.03.84

Kock N (2015) Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int J e-Collaboration 11(4):1–10. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100101

Lam LW, Lau DC (2012) Feeling lonely at work: investigating the consequences of unsatisfactory workplace relationships. Int J Hum Resour Manag 23(20):4265–4282. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.665070

Lan YY, Qu XT, Xia YH (2020) The influence of servant leadership on employee creativity: the mediating role of knowledge sharing behavior and the moderating role of leader-follower value congruence. Hum Resour Dev China 37(11):37–49. https://doi.org/10.16471/j.cnki.11-2822/c.2020.11.003

Levinson H, Price CR, Munden KJ, Mandl HJ, Solley CM (1962) Men, management, and mental health. Harvard University Press

Liden RC, Wayne SJ, Liao C, Meuser JD (2014) Servant leadership and serving culture: influence on individual and unit performance. Acad Manag J 57(5):1434–1452. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0034

Liden RC, Wayne SJ, Meuser JD, Hu J, Wu J, Liao C (2015) Servant leadership: validation of a short form of the SL-28. Leadersh Quar 26(2):254–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.12.002

Li CH, Ye ML (2015) Review on workplace loneliness. China Human Resource Development, (11): 29-37. https://doi.org/10.16471/j.cnki.11-2822/c.2015.11.006

Li N (2020) Research on incentive strategies for the new generation of employees born after 1995 in small and medium-sized enterprises – based on psychological contract theory. Mod Bus Trade Ind 41(32):66–68

Li J (2022) The impact of supervisor incivility on employees’ organizational citizenship behavior. Dissertation, Guangxi University of Science and Technology

Lin YZ (2019) The relationship between servant leadership, workplace loneliness, and nurses’ turnover intention. Dissertation, Guangxi University

Liu CZ (2011) The impact of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior. Dissertation, Hunan University

Liu C, Liu J, Zhu L (2016) Team territory behaviour and knowledge sharing behaviour: based on the perspective of identity theory. Human Resources Development of China, (21): 61-70

Liu MZ (2020) Research on the double-edged sword effect of servant leadership on hotel frontline employees’ service innovation behavior. Dissertation, Jinan University

Liu J, Wang X (2021) Analysis on the mechanism of digital economy affecting enterprise life span. Sci Tech Inf Gansu 11(50):65–67. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-6375.2021.11.020

Lu J, Cheah PK, Falahat M (2022) A conceptual model for servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior. in International conference on business and technology (pp. 299-308). Springer International Publishing, Cham

Neubert MJ, Hunter EM, Tolentino RC (2016) A servant leader and their stakeholders: When does organizational structure enhance a leader’s influence? Leadersh Quar 27(6):896–910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.05.005

Newman A, Schwarz G, Cooper B, Sendjaya S (2017) How servant leadership influences organizational citizenship behavior: the roles of LMX, empowerment, and proactive personality. J Bus Ethics 145(1):49–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2827-6

Ma J, Liu L (2020) Study on the relationships among inclusive leadership, relational identification, and followership: the moderation of power distance. Hebei J Ind Sci Technol 37(2):59–68. https://doi.org/10.7535/hbgykj.2020yx02002

Morrison EW, Robinson SL (1997) When employees feel betrayed: a model of how psychological contract violation develops. Acad Manag Rev 22(1):226–256. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1997.9707180265

Organ DW (1988) Organizational citizenship behavior: the good soldier syndrome. Lexington Books/D. C. Heath and Com

Organ DW, Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB (2006) Organizational citizenship behavior: its nature, antecedents, and consequences. Sage, Beverly Hills, CA

Ozcelik H, Barsade S (2011) Work loneliness and employee performance. In Academy of management proceedings (Vol. 2011, No. 1, pp. 1-6). Briarcliff Manor: Academy of Management. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2011.65869714

Ozcelik H, Barsade SG (2018) No employee an island: workplace loneliness and job performance. Acad Manag J 61(6):2343–2366. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2015.1066

Peng J, Chen Y, Xia Y, Ran Y (2017) Workplace loneliness, leader-member exchange and creativity: The cross-level moderating role of leader compassion. Personal Individ Differ 104:510–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.09.020

Promsri C (2018) Relationship between loneliness in the workplace and deviant work behaviors: evidence from a Thai Government Bank. Soc Sci Humanities J 2(3):352–357

Qu KJ, Zou H, Yu YB (2010) The relationship between loneliness and personalities in adolescent students: the mediating effect of interpersonal competence. Psychol Explor 30(6):75–80

Qu R, Janssen O, Shi K (2015) Transformational leadership and follower creativity: the mediating role of follower relational identification and the moderating role of leader creativity expectations. Leadersh Quar 26(2):286–299. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1003-5184.2010.06.015

Raja U, Johns G, Ntalianis F (2004) The impact of personality on psychological contracts. Acad Manag J 47(3):350–367. https://doi.org/10.5465/20159586

Reed L (2016) Servant leadership, followership, and organisational citizenship behaviours in 9-1-1 emergency communications centers: Implications of a national study. Servant Leadersh: Theory Pract 2(1):71–94

Rhoades L, Eisenberger R (2002) Perceived organizational support: a review of the literature. J Appl Psychol 87(4):698–714. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.698

Rockstuhl T, Eisenberger R, Shore LM, Kurtessis JN, Ford MT, Buffardi LC, Mesdaghinia S (2020) Perceived organizational support (POS) across 54 nations: a cross-cultural meta-analysis of POS effects. J Int Bus Stud 51(6):933–962. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-020-00311-3

Rousseau DM (1989) Psychological and implied contracts in organizations. Empl Responsib Rights J 2(2):121–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01384942

Rousseau DM (1990) New hire perceptions of their own and their employer’s obligations: a study of psychological contracts. J Organ Behav 11(5):389–400. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030110506

Rousseau DM (1995) Psychological contracts in organizations: understanding written and unwritten agreements. Sage publications

Ruiz- Palomino P, Linuesa-Langreo J, Elche D (2023) Team- level servant leadership and team performance: the mediating roles of organizational citizenship behavior and internal social capital. Bus Ethics Environ Responsib 32(52):127–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12390

Russell D, Peplau LA, Cutrona CE (1980) The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J Personal Soc Psychol 39(3):472–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472

Schumacker RE, Lomax RG (2010) A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ

Shmueli G, Sarstedt M, Hair JrJF, Cheah JH, Ting H, Vaithilingam S, Ringle CM (2019) Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: guidelines for using PLS predict. Eur J Mark 53(11):2322–2347. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-02-2019-0189

Sluss DM, Ashforth BE (2007) Relational identity and identification: defining ourselves through work relationships. Acad Manag Rev 32(1):9–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.23463672

Sluss DM, Ashforth BE (2008) How relational and organizational identification converge: processes and conditions. Organ Sci 19(6):807–823. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1070.0349

Sluss DM, Ashforth BE, Gibson KR (2012) The search for meaning in (new) work: task significance and newcomer plasticity. J Vocat Behav 81(2):199–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.07.002

Song ZW (2020) The impact of paternalistic leadership on employees’ compulsory citizenship behavior: a moderated mediation model. Dissertation, He Bei University

Steffens NK, Haslam SA, Reicher SD (2014) Up close and personal: evidence that shared social identity is a basis for the ‘special’ relationship that binds followers to leaders. Leadersh Quar 25(2):296–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.08.008

Tajfel H, Turner JC (1986) The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7-24). Nelson-Hall

Thompson PS, Bergeron DM, Bolino MC (2020) No obligation? How gender influences the relationship between perceived organizational support and organizational citizenship behavior. J Appl Psychol 105(11):1338–1350. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000481

Van Knippenberg D (2000) Work motivation and performance: a social identity perspective. Appl Psychol 49(3):357–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00020

Vinod S, Sudhakar B (2011) Servant leadership: a unique art of leadership. Interdiscip J Contemp Res Bus 2(11):456–467

Wang Q, Li L, Wang GX (2019) The impact mechanism of workplace loneliness on job engagement: the roles of leader-member exchange and traditionality. Modern Manag Sci (7):87–89

Wang LT, Yang L (2010) A review of research on psychological contract breach. Cooperative Econ Sci Technol 394:42–44

Wang YL (2022a) A literature review on paternalistic leadership. China Collective Econ (29):109-111

Wang ZY (2022b) Incentives, identification, and behavior: exploring organizational citizenship behavior among tourism major students during internships. Dissertation, Qingdao University

Wright SL (2005) Loneliness in the workplace. Dissertation, University of Canterbury

Wei W, Huang CY, Zhang Q (2019) The influence of negative mood on organizational citizenship behavior and counterproductive work behavior: a self-control perspective. Manag Rev 31(12):146–158. https://doi.org/10.14120/j.cnki.cn11-5057/f.2019.12.013

Wu J, Liden RC, Liao C, Wayne SJ (2021) Does manager servant leadership lead to follower serving behaviors? It depends on follower self-interest. J Appl Psychol 106(1):152–167. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000500

White CA, Slater MJ, Turner MJ, Barker JB (2021) More positive group memberships are associated with greater resilience in Royal Air Force (RAF) personnel. Br J Soc Psychol 60(2):400–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12385

Xu YY, Lin XQ, Xi YH (2019) When do lonely employees become more engaged: the intervention effects of future work self-clarity and transformational leadership. Nankai Bus Rev 22(5):79–89

Yoshida DT, Sendjaya S, Hirst G, Cooper B (2014) Does servant leadership foster creativity and innovation? A multi-level mediation study of identification and prototypicality. J Bus Res 67(7):1395–1404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.08.013