Abstract

This study examines the indirect effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior through perceptions of organizational politics moderated by political skill. This study reports the responses of 321 respondents from six federal public service organizations in Ethiopia. A multi-stage random sampling procedure was employed to select the sampled federal public service organizations. To test hypotheses, the study employed structural equation modeling using AMOS version-26 software. The result revealed that all direct effects have a significant effect. Specifically, servant leadership has a positive effect on organizational citizenship behavior. Likewise, servant leadership has a negative effect on perceptions of organizational politics. Also, a perception of organizational politics has a negative effect on organizational citizenship behavior. Moreover, perceptions of organizational politics competitively mediated the effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior. As well, political skill moderated the effect of perceptions of organizational politics on organizational citizenship behavior but not the indirect effect. To the best of our knowledge, no one else employs perceptions of organizational politics as a mediating effect between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior. Furthermore, we are not aware of anyone else employing political skill as a moderating role in the indirect effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior through perceptions of organizational politics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Organizational citizenship behavior refers to extra-role employee acts that are not formally acknowledged or rewarded by the organization but that contribute to its effective functioning (P. M. Podsakoff et al., 2000). According to the literature on organizational behavior, organizational citizenship behavior includes things like helping colleagues with work-related issues, volunteering for tasks outside of one's job description, and being a positive ambassador for the organization (Brubaker et al., 2015; Huei et al., 2014; Turnipseed & Turnipseed, 2013). Organizational citizenship behavior significantly affects organizational success by establishing a feeling of shared purpose, cooperation, collaboration, a good work environment, and environmental sustainability (Dash & Pradhan, 2014; Huei et al., 2014; Ingrams, 2020; Obedgiu et al., 2020). Employees who engage in behaviors such as helping, cooperating, and showing concern for others contribute to the development of a collaborative and supportive (positive) work climate (Dash & Pradhan, 2014; de Geus et al., 2020; Huei et al., 2014; Ingrams, 2020). This positive climate enhances employee satisfaction, morale, and commitment, ultimately leading to higher productivity and better outcomes (de Geus et al., 2020; Ingrams, 2020).

Despite the fact that organizational citizenship behavior has been shown by a variety of researchers to increase organizational effectiveness, Kumasey et al. (2017) found that employees of public service organizations are less committed to practicing organizational citizenship behavior than those in the private sector. Because of this, service delivery in public service organizations is inefficient (de Geus et al., 2020; Ingrams, 2020). Investigating the reasons behind why workers in public service organizations are not dedicated to exhibiting organizational citizenship behavior is vital. De Geus et al. (2020) made the suggestion that further study is required to examine the factors that affect organizational citizenship behavior in public service organizations. To end with, the study takes as an initial research gap to conduct the present research.

One of the best ways to encourage organizational citizenship is through servant leadership (Amir, 2019; Bambale et al., 2015; Elche et al., 2020; Qiu & Dooley, 2022). Servant leadership is a leadership approach that emphasizes the leader's role as a servant to their followers, focusing on their needs, growth, and development (Dannhauser, 2007; Dittmar, 2006; van Dierendonck & Nuijten, 2011). Similarities exist between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior, notably in the area of role modeling (Ehrhart, 2004; Walumbwa et al., 2010). Servant leaders provide an example for their employees by acting with integrity, humility, and empathy (Dannhauser, 2007; Dittmar, 2006; van Dierendonck & Nuijten, 2011). This example of good behavior might encourage subordinates to take similar actions (Ehrhart, 2004; Walumbwa et al., 2010). Employees are more likely to be encouraged to act similarly when they see their leaders engaged in organizational citizenship behavior (Amir, 2019; Bambale et al., 2015; Elche et al., 2020; Qiu & Dooley, 2022). Employees are inspired to actively participate in organizational citizenship behavior by seeing the servant leader's dedication to going beyond the requirements of their jobs (Bambale et al., 2015; Ehrhart, 2004).

Although this significance has been acknowledged, the link between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior was found to be uneven and inconclusive. For instance, Mahembe and Engelbrecht (2014) and Elche et al. (2020) have revealed a significant link between the constructs, while others found it non-significant (e.g., Harwiki, 2013; Strajhar et al., 2016). To end with, the study takes the ‘black box’ issue in the link between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior as a second research gap to conduct the current study.

The ‘black box’ issue in the link clearly shows that there is a clear need for research by considering potential intervening or mediating variables that may explain the effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior. Due to this, prior studies helped to improve knowledge of the underlying processes explaining the link by studying different mediating variables, for instance, organizational justice (Zehir et al., 2013), organizational commitment (Harwiki, 2013), organizational culture (Harwiki, 2013), public service motivation (Gnankob et al., 2022), service climate and empathy (Elche et al., 2020), job embeddedness (Zia et al., 2022), leader-member dyadic communication role (Abu Bakar & McCann, 2016), service climate (Walumbwa et al., 2010), and psychological empowerment (Aziz et al., 2018). While previous researchers have identified different mediating variables, there is still a need to better understand the underlying mechanisms that explain this link (Hanaysha et al., 2022; Jafaat et al., 2014; Zehir et al., 2013). In this respect, perceptions of organizational politics are considered a relevant mediation variable in the link. This is because some researchers suggest that perceptions of organizational politics may play a mediating role in the link between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior (Khattak et al., 2022; Qiu & Dooley, 2022). Perceptions of organizational politics refers to employees' perceptions of the use of power and influence in the organization for personal gain or to further the interests of certain groups, often at the expense of others (Vigoda & Cohen, 2002).

The study argues that the potential mediating role of perceptions of organizational politics in the link between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior can be supported by servant leadership theory. Servant leadership theory suggests that leaders characterized by their focus on serving others have the potential to shape employees' perceptions of the organizational climate and their inclination to engage in organizational citizenship behavior (Eva et al., 2019; Liden et al., 2008, 2014; Walumbwa et al., 2010). Servant leadership emphasizes justice and transparency to promote a positive and supportive work atmosphere (Liden et al., 2014). By fostering an atmosphere of justice and transparency, they reduce employees' perceptions of political behaviors such as self-interest and favoritism (Khattak et al., 2022). As a result, employees are more likely to believe that the organization is honest and fair, which has a beneficial effect on how eager they are to exhibit organizational citizenship behavior (Byrne, 2005; Khan et al., 2019; Mathur et al., 2013; Shafiq et al., 2017). Based on this argument, the mediating role of perceptions of organizational politics is explained in the present study as: if leaders who are viewed as not servants by their subordinates run the risk of decline in citizenship behavior due to an increase in perceptions of organizational politics and vice versa.

Another reason why perceptions of organizational politics are a relevant mediating variable is because of the Ferris and Rowland (1981) argument. Ferris and Rowland (1981) stated that perceptions of the workplace can mediate between leadership and subordinate outcomes. Ferris & Rowland argued that leaders who are perceived as unfair, unsupportive, or untrustworthy may contribute to negative perceptions and lower outcomes. In line with this argument, different scholars (e.g., Islam et al., 2013; Kacmar et al., 2013; Khuwaja et al., 2020; Kimura, 2012; Saleem, 2015; Vigoda-Gadot, 2007) examined perceptions of organizational politics as a mediator in the different leadership styles (e.g., transformational leadership style, ethical leadership style, e.t.c.)–organizational citizenship behavior link, and perceptions of organizational politics have been found to mediate the links. Therefore, the present researchers propose that perceptions of organizational politics work in a similar manner in the servant leadership–organizational citizenship behavior links. Thus, understanding the mediating role of perceptions of organizational politics in the link between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior is important to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the determinants of organizational citizenship behavior. Since there are no empirical studies revealing the mediating role of perceptions of organizational politics, this study fills such a gap. To end with, the present study takes this as a third research gap to conduct the current study.

However, the link between how employees perceive organizational politics and their organizational citizenship behavior is not straight-forward (Tripathi et al., 2023). In this respect, some scholars suggested that the link between perceptions of organizational politics and organizational citizenship behavior depends on employees' political skills (Bing et al., 2011; Kacmar et al., 2013; Tripathi et al., 2023). Authors like Kacmar et al. (2013) argue that it is essential to consider individual differences when investigating the effect of perceptions of organizational politics on organizational citizenship behavior. The term political skill refers to individual differences that relate to a person's ability to understand and successfully manage political situations in an organization (Ferris et al., 2005). Political skills can influence how individuals perceive, interpret, and respond to organizational politics (Kacmar et al., 2013). Employees with higher levels of political skill may perceive and interpret organizational politics differently from those with lower political skill (Ferris et al., 2007; Kacmar et al., 2013; Kaur & Kang, 2020). Employees with higher levels of political skill may be better equipped to navigate the political environment of the organization and maintain a positive attitude towards organizational citizenship behavior, even in the presence of perceived politics (Bing et al., 2011; Kacmar et al., 2013; Tripathi et al., 2023). Employees with lower levels of political skill may be more vulnerable to the negative effects of perceived politics on their attitudes and behaviors, leading to reduced organizational citizenship behavior (Bing et al., 2011; Kacmar et al., 2013; Tripathi et al., 2023). To the end, the present study suggests that the strength of the link between perceptions of organizational politics and organizational citizenship behavior will be stronger for employees with lower levels of political skill, and weaker for employees with higher levels of political skill. Therefore, the present study aims to contribute to the scant literature by examining how political skill moderates the effect of perceptions of organizational politics on organizational citizenship behavior.

Furthermore, the current study employs a moderated mediation (conditional mediation) model. Moderated mediation (conditional mediation) is a statistical framework that integrates aspects of both mediation and moderation analyses, aiming to explore how the mediating effect of a variable (in this case, perceptions of organizational politics) depends upon the moderator value (in this case, political skill) (Hayes, 2015a). Integrating the logic associated with perceptions of organizational politics as a mediating variable and political skill as a moderator, the present researchers produce a moderated-mediation framework. The study examines whether the mediation role of perceptions of organizational politics between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior is influenced by the level of political skill exhibited by employees. The implementation of a moderated mediation model facilitates the exploration of how the indirect relationship between leadership and organizational citizenship behavior, mediated by perceptions of organizational politics, is moderated by individual differences in political skill (Kacmar et al., 2013). To the end, the present study proposes that the strength of the mediating effect of perceptions of organizational politics on the link between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior will be stronger for employees with lower levels of political skill and weaker for employees with higher levels of political skill. To the best of the present researcher’s knowledge, no previous research has examined the moderating role of political skill in the indirect effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior through perceptions of organizational politics. Hence, the current researchers take this as the fourth research gap to conduct the current study.

Finally, discuss the gap is related to the context gap. The empirical review reveals that most of the study was conducted in developed countries (Abdelmotaleb & Saha, 2019; Iqbal et al., 2018) and business organizations such as hotels (Elche et al., 2020; Karatepe, 2013; Qiu & Dooley, 2022; Wu et al., 2013; Zia et al., 2022), banks (Shah et al., 2015; Song et al., 2022), the education sector (Güçel et al., 2012; Khattak et al., 2022; Salehi & Gholtash, 2011; Sudarsana Rao et al., 2017), non-government organizations (Brubaker et al., 2015), and manufacturing (Dash & Pradhan, 2014; Kumari et al., 2022; Sharma & Sangeeta, 2014). This implies that previous studies haven’t drawn much attention in the public institution setting, indicating that study in public service organizations is lacking, although the sector is strategic and relevant for the development of countries. Regarding this, Knies et al. (2017) stated that the welfare of the country depends on the performance of public service organizations. Tensay and Singh (2020) added that public service organizations are the backbones of the economy and the basic sectors for social and economic development to achieve the country's vision. However, public service organizations fall short in meeting the public’s expectations, especially in developing nations (Gnankob et al., 2022; Vidal, 2014). Therefore, this study aimed at addressing the gap by examining the effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior through the mediation role of perceptions of organizational politics, moderated by political skill in the public service setting, and adding the literature to minimize the outcome of inconsistency. Also this is the first study of its kind in federal public service organizations.

Review of Related Literature

Organizational Citizenship Behavior

The organizational citizenship behavior concept can be originally traced to the work of Chester Barnard in 1938 in his theory of cooperative systems. Barnard defined organizations as cooperative systems in which individuals work together to achieve common goals (Barnard, 1938). Barnard also stressed that the “willingness of persons to contribute efforts to the cooperative system is indispensable.” These arguments suggest that the willingness to cooperate among employees is crucial for achieving organizational goals and objectives. Barnard’s (1938) willingness to cooperate idea and organizational citizenship behavior are conceptually similar as they both are voluntary (P. M. Podsakoff et al., 2000). What Organ referred to organizational citizenship behavior as "discretionary behavior" in the previous three decades was Barnard's willingness to cooperate, which has been documented in the literature for more than seven decades (Bambale et al., 2015; Ocampo et al., 2018; P. M. Podsakoff et al., 2000).

Smith et al. (1983) were the first scholars to introduce the concept of organizational citizenship behavior. Smith et al. defined the following organizational citizenship behavior subscales: altruism (e.g., helps others who have been absent; volunteers for things that are not required; orients new people even though it is not required; helps others who have heavy workloads) and compliance (e.g., punctuality; attendance at work is above the norm; gives advance notice if unable to come to work; does not take extra breaks; does not spend time in idle conversations).

The definition of organizational citizenship behavior can vary depending on the author, but most definitions share some common characteristics. All definitions suggest that organizational citizenship behavior is an extra-role behavior that employees engage in, which goes beyond their formal job requirements and is directed towards the effective functioning of the organization (de Geus et al., 2020; Ocampo et al., 2018). Over the four decades of organizational citizenship behavior research, the construct has been conceptualized in several ways (e.g., Podsakoff et al., 2000; Smith et al., 1983; Williams & Anderson, 1991). However, Podsakoff et al. (2009) reported that the most popular conceptualizations are the dimensions developed by Williams and Anderson (1991), which were later validated by Lee and Allen (2002). In recent years, many scholars have begun to underscore the importance of organizational citizenship behaviors in public service organizations. Organizational citizenship behavior findings have encouraged public service organizations to use citizenship behavior to increase organizational performance (de Geus et al., 2020). Obedgiu et al. (2020) described that when engaging in organizational citizenship behavior, civil servants are seeking ways of enhancing organizational performance by contributing to a better organizational culture and providing better services. Obedgiu et al. (2020) stated that organizational citizenship behavior is a possible solution to meeting citizen satisfaction as it is among the important factors influencing organizational efficiency. de Geus et al. (2020) assert that organizational citizenship behavior has special importance due to the relevance of generalized citizenship in government-citizen relationships and the goals of public administration reforms to achieve greater organizational responsiveness to citizens. de Geus et al. (2020) also describe that, while growth was relatively steady in the private sector, studies in the public sector took longer to develop and have lately started. According to a review of the literature, organizational citizenship behaviors enhance productivity, resource efficiency, teamwork, the workplace environment, employee retention, performance stability, and an organization's capacity to adapt to environmental change (de Geus et al., 2020; Ingrams, 2020; Obedgiu et al., 2020).

Servant Leadership

The idea of servant leadership has its roots in ancient philosophy and religious texts. Servant leadership was prominent in spirituality (Mark 10:43) and exemplified by Jesus to his disciples by stating that “Whoever wants to be a leader must be a servant” (Brewer, 2010). The idea was initiated and introduced into contemporary social organizations by American management and leadership scholar Greenleaf in the 1970s (Frick, 2004). When he came up with the idea of servant leadership as an alternative leadership paradigm, Greenleaf argued it as a “better leadership approach that puts serving others including followers, customers, and the community, as the number one priority (Frick, 2004).

Through the creation of several measurements for evaluating servant leadership's characteristics, several scholars have significantly advanced the study of servant leadership. Listening, empathy, healing, awareness, persuasion, conceptualization, foresight, stewardship, dedication to the growth of people, and community building were among the 10 qualities of servant leaders listed by Spears et al., (1996). Spears viewed servant leadership as not a sub-theory but as a complete theory of leadership. Vision, credibility, trust, and service were recognized by Farling et al. (1999) as essential elements of servant leadership, with an emphasis on the prioritizing of followers' needs, empowerment, and the promotion of a collaborative and community-oriented culture. The Organizational Leadership Assessment (OLA) instrument was created by Laub (1999) and is based on Larry Spears' criteria of servant leadership. It evaluates a leader's capacity for respecting and developing others, building community, and exhibiting authenticity. Ehrhart (2004) created the Organizational Citizenship Behavior Servant Leadership (OCBSL) measure to evaluate the characteristics of servant leadership that promote organizational citizenship behavior. The Servant Leadership Questionnaire (SLQ), developed by Barbuto and Wheeler in 2006, measures servant leadership behaviors and attitudes in areas such as altruistic calling, emotional healing, persuasive mapping, wisdom, and organizational stewardship. The Servant Leadership Scale (SLS), which was established by Liden et al. (2008), includes prioritizing subordinates, putting the community's needs before one's own, and resolving emotional issues. The Servant Leadership Survey (SLS), a multi-dimensional scale that includes aspects like empowerment, responsibility, humility, authenticity, courage, forgiveness, and stewardship, was developed by Dierendonck and Nuijten in 2011. Overall, the idea of servant leadership has been articulated and investigated by a range of academics. Though there may be variances in emphasis and approach, the common definition of servant leadership is a commitment to serving the needs of others and creating a supportive work environment (Liden et al., 2014).

Perceptions of Organizational Politics

There are three approaches that dominate the literature on organizational politics: (1) studies on influence tactics and actual political behavior; (2) studies on perceptions of organizational politics; and (3) studies on political skill. This study focused on perceptions of organizational politics. The Lewin (1936) idea that people react based on their perceptions of reality rather than on objective reality was the foundation of the perceptions of organizational politics approach (Kimura, 2012). For most employees within an organization, and indeed for the public in general, what determines an individual’s reaction to a particular situation is undoubtedly their perception rather than the reality of that situation per se (Cheng et al., 2019). Decades of empirical research have indicated that perceptions of organizational politics in the workplace have received negative responses from employees (Kacmar et al., 2013). Some researchers also argued that if the organizational environment is political, employees’ investment in the organization becomes more risky (Hochwarter et al., 2003). In a political environment, incentives are frequently given based on informal power structures rather than on contributions or efforts, and the rules may vary from day to day (Kimura, 2012). Because of this uncertainty, individuals are less likely to be confident that their efforts will produce any outcomes beneficial to themselves (Kacmar et al., 2013). Therefore, reducing employees’ perceptions of organizational politics should be viewed as an important issue both in the theory and practice of organizational management (Kimura, 2012).

Political skill

The term political skill has been in organizational literature for about five decades. While Pfeffer (1981) and Mintzberg (1983) advanced the notion of political skill in organizational management, later Ferris and Michele Kacmar (1992) and Perrewé et al., (2000) reintroduced the concept in the mainstream study. Since organizations are inherently political arenas, political skills sre appropriate to navigate social interactions and relations (Mintzberg, 1985). Political skill refers to the ability to understand people at work and use that understanding to persuade others to act in ways that further organizational objectives (Ahearn et al., 2004). The control an employee has over their work environment, including how they perceive and react to the workplace political environment, is dependent on the employee’s political skills (Andrews et al., 2009). Politically skilled employees can maneuver political organizations, which enables them to increase favorable outcomes and decrease unfavorable ones (Crawford et al., 2019). Politically skilled employees are able to more effectively navigate political environments, as their heightened understanding of people and environments provides them with insight into what performance is necessary to achieve desired outcomes in political contexts (Kacmar et al., 2013). Politically skilled employees, due to their capability, are likely to view perceptions of organizational political situations as less threatening and neutralize their impact (Crawford et al., 2019). Previous perceptions of organizational politics scholars viewed political skill as an essential asset for being effective (Kacmar et al., 2013). As organizations continue to become more complex, the ability to effectively navigate the political dynamics of the workplace is likely to become even more important (Ahearn et al., 2004; Ferris et al., 2005; Kacmar et al., 2013).

Servant Leadership and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

In the context of organizational citizenship behavior, servant leadership can affect employee behavior in several ways. By acting as a role model for subordinates, servant leaders promote organizational citizenship behavior in a significant way (Ehrhart, 2004; Liden et al., 2014; Mahembe & Engelbrecht, 2014). Empathy, humility, and integrity are qualities that servant leaders continually display (Liden et al., 2014). Employees are inspired by their leaders' behavior to adopt these traits and participate in organizational citizenship behavior (Yukl, 2002; Trong Tuan, 2017). For instance, when a servant leader continually goes beyond to assist others, employees are likely to engage in similar acts of citizenship (Trong Tuan, 2017). Furthermore, when servant leaders care about their employees' well-being, they are seen as admirable and honest, and as a result, the employees may feel psychologically forced to engage in organizational citizenship behavior (Ehrhart, 2004; Liden et al., 2014; Mahembe & Engelbrecht, 2014). Chon & Zoltan (2019) also asserted that when servant leaders express strong concern for the needs of their followers and treat followers fairly, these may arouse organizational citizenship behavior from the employees in return. Overall, servant leadership promotes the development of prosocial ideals by acting as a role model, promoting psychological safety and trust, and empowering employees (van Dierendonck, 2011). These factors all work to favorably affect organizational citizenship behavior (Elche et al., 2020; Gnankob et al., 2022; Mathur & Negi, 2014a, b; Strajhar et al., 2016; Zehir et al., 2013). These mechanisms foster an atmosphere where workers are more inclined to act in organizational citizenship ways that advance the organization's performance as a whole (Bambale et al., 2015; Liden et al., 2008, 2014). Therefore, in light of the above argument, the present study suggests the following hypotheses:

-

Hypothesis 1: Servant leadership has a positive effect on organizational citizenship behavior.

Servant Leadership and Perceptions of Organizational Politics

According to the servant leadership theory, leaders who put their followers' well-being, growth, and development first can have a significant effect on various aspects of the work environment (Greenleaf, 1977). One area where servant leadership may have an impact is how people view their organization as political (Khattak et al., 2022). Self-interest, manipulation, and the pursuit of individual agendas are all characteristics of organizations that are political, which can lead to unfavorable and unhealthy workplace conditions (Hochwarter, 2012; Ferris et al., 2007). On the other side, servant leaders display a different set of behaviors and values (van Dierendonck, 2011). They place a high value on honesty and making ethical decisions (Liden et al., 2008). These traits of servant leadership may lessen employees’ views of organizations as political (Khattak et al., 2022). Another way in which servant leadership may affect perceptions of organizational politics is through the establishment of fairness and justice (Kaya et al., 2016; Khattak & O’Connor, 2021). Servant leaders work to provide settings in which employees are treated fairly and decisions are made using objective standards (Khuwaja et al., 2020; Liden et al., 2008). This emphasis on fairness and justice reduces perceptions of political behavior, as employees feel that their interests are being considered and that decisions are not influenced by personal agendas (Khattak et al., 2022).

Moreover, by fostering transparency and trust, servant leadership can affect perceptions of organizational politics (Kaya et al., 2016; Khattak & O’Connor, 2021). Servant leaders encourage a culture that values transparent and open communication (Liden et al., 2008). By being transparent in their decision-making processes, servant leaders build trust with their employees (Thakore, 2013). When employees perceive their leaders as trustworthy and believe that decisions are made with integrity and fairness, their perceptions of organizational politics will be minimized (Kaya et al., 2016). Overall, servant leaders create an atmosphere where views of political behavior are reduced via the building of trust and openness, the promotion of fairness and justice, the empowering of workers, and the nurturing of an ethical climate (Kaya et al., 2016; Khattak & O’Connor, 2021). Thus, organizations can create a healthier work environment and increase organizational productivity by implementing servant leadership principles. In light of the above argument, the present study suggests the following hypotheses:

-

Hypothesis 2: Servant leadership has a negative effect on perceptions of organizational politics.

Perceptions of Organizational Politics and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Organizational citizenship behavior is significantly influenced by how people perceive organizational politics (Atta Mohsin & Muhammad Jahanzeb Khan, 2016; Tripathi et al., 2023). Employees who perceive a high degree of organizational politics that is driven by self-interest, favoritism, and injustice may lose faith in the system and stop engaging in extra-role activities like organizational citizenship behavior (Kaur & Kang, 2020; Tripathi et al., 2023). The perception of political behavior creates a negative work atmosphere, leading workers to question the fairness of the organization (Ferris et al., 2007). As a result, workers can be less inclined to practice organizational citizenship, which includes actions like helping coworkers and volunteering for extra work (Khattak et al., 2022; Khattak & O’Connor, 2021; Obedgiu et al., 2020; Randall et al., 1999; Ferris et al., 2002). In light of the above argument, the present study suggests the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 3: Perceptions of organizational politics have a negative effect on organizational citizenship behavior.

Perceptions of Organizational Politics as a Mediating Role Between Servant leadership and Organizational citizenship behavior

Perceptions of organizational politics can serve as a mediating role in explaining the effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior. Servant leadership, characterized by its focus on serving others, has the potential to shape employees' perceptions of the organizational climate and their inclination to engage in organizational citizenship behavior (Dierendonck & Nuijten, 2011; Liden et al., 2008). Servant leaders create a positive and supportive work environment, emphasizing transparency, fairness, and ethical decision-making (Liden et al., 2008). By fostering an atmosphere of trust and openness, servant leaders reduce employees' perceptions of political behaviors such as self-interest and favoritism (Kaya et al., 2016; Khattak & O’Connor, 2021). Consequently, employees are more likely to perceive the organization as fair and trustworthy, which positively influences their willingness to engage in organizational citizenship behavior (Liden et al., 2014). Based on this argument, the mediating role of perceptions of organizational politics is explained as: if leaders who are viewed as not servants by their subordinates run the risk of decline in citizenship behavior due to an increase in perceptions of organizational politics and vice versa.

Moreover, perceptions of organizational politics have been found to mediate the relationships between different leadership styles (e.g., transformational leadership style, ethical leadership style, e.t.c.) and organizational citizenship behavior (e.g., Islam et al., 2013; Kacmar et al., 2013; Khuwaja et al., 2020; Kimura, 2012; Saleem, 2015; Vigoda-Gadot, 2007). These researchers argue that leaders who are perceived as unfair, unsupportive, or untrustworthy may contribute to negative perceptions and a lower outcome (Islam et al., 2013; Kacmar et al., 2013; Khuwaja et al., 2020; Kimura, 2012; Saleem, 2015; Vigoda-Gadot, 2007). Based on the justification from the existing empirical evidence, the present study proposes that perceptions of organizational politics work in a similar manner in the servant leadership–organizational citizenship behavior relationships. Therefore, this research will contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms through which servant leadership impacts organizational outcomes, shedding light on the importance of reducing perceptions of organizational politics. In light of the above argument, the present study suggests the following hypotheses:

-

Hypothesis 4: Perceptions of organizational politics mediate the link between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior, such that the positive effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior is weakened when perceived organizational politics is high.

Political Skill as a Moderating Role between Perceptions of Organizational Politics and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

The nexus between how employees perceive organizational politics and their organizational citizenship behavior is not straight-forward (Tripathi et al., 2023). The moderating role of political skill can influence the link between perceptions of organizational politics and organizational citizenship behavior (Andrews et al., 2009; Ferris et al., 2005, 2007; Kacmar et al., 2013). When researching how views of organizational politics affect organizational citizenship behavior, it is crucial to take individual differences like political skill into account (Bing et al., 2011; Kacmar et al., 2013). Political skill can influence how individuals perceive, interpret, and respond to organizational politics (Bing et al., 2011; Kacmar et al., 2013). Individuals with higher levels of political skill may perceive and interpret organizational politics differently from those with lower levels of political skill (Kaur & Kang, 2020). Employees with higher levels of political skill may be better equipped to navigate the political environment of the organization and maintain a positive attitude towards organizational citizenship behavior, even in the presence of perceived politics (Bing et al., 2011; Kacmar et al., 2013; Tripathi et al., 2023). Because they are able to comprehend that politics is natural and inevitable in organizations (Ferris et al., 2005). Organizational politics is inevitable and unavoidable (Cliffs, 1984). Employees low in political skill view the existence of perceptions of organizational politics negatively, as they lack the sufficient resources to control the uncertainty manifested in high political environments (Bing et al., 2011; Kacmar et al., 2013). To the end, the present study proposes that the effect of perceptions of organizational politics on organizational citizenship behavior will be stronger for employees with lower levels of political skill and weaker for employees with higher levels of political skill. In light of the above argument, the study suggests the following hypotheses:

-

Hypothesis 5: Political skill can moderate the effect of perceptions of organizational politics on organizational citizenship behavior

Moderating Role of Political Skill in the Indirect Effect of Servant Leadership on Organizational Citizenship Behavior through Perceptions of Organizational Politics

While the present study believes that perceptions of organizational politics mediate the effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior, previous scholars have revealed that perceptions of organizational politics depend on employees’ levels of political skill (Bing et al., 2011; Kacmar et al., 2013; Tripathi et al., 2023). Moderated mediation is a framework that integrates mediation and moderation analyses to examine and test hypotheses about how mediated relationships vary as a function of context or individual differences (moderator value) (Cheah et al., 2021). Integrating the logic associated with perceptions of organizational politics as a mediating variable and political skill as a moderator, the present study produces a moderated-mediation framework. Moreover, Preacher et al. (2007) stated that when the ‘b_ Path’ is moderated by ‘W’, commonly referred to as a moderated mediation model. Preacher et al, (2007) added that in moderated mediation, the effect of X (the independent variable) on Y (the dependent variable) through M (the mediation variable) is not constant but varies depending on the level of the moderator variable (W). This implies that the indirect effect of X on Y through M is also contingent upon the value of the moderator variable (Preacher et al., 2007). Based on this argument, the present study was conducted to determine whether the strength of the mediation effect varies based on the levels of moderator value. In light of the above logic, the present study suggests the following hypotheses:

-

Hypothesis 6: Political skill can moderate the mediation effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior through perceptions of organizational politics.

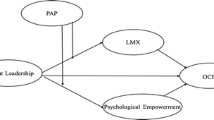

Conceptual Framework (Fig. 1)

Conceptual framework. Note: X = independent variable, Y = dependent variable, M = mediator variable, W = moderator variable. a_path means from ‘X’ to ‘M’, b_path means from ‘M’ to ‘Y’, c_path means from ‘X’ to ‘Y’ and d_path means from ‘W’ to ‘Y’. The research model is adopted from Ehrhart (2004), Kacmar et al. (2013), Kaur etal., (2023), and Preacher et al. (2007)

Methodology

A multi-stage random sampling procedure was employed, considering the nature of the sectors as strata. The federal public service organizations were first divided into three sectors (strata), and then two organizations were chosen at random from each sector. The sample organizations were chosen at random using this procedure: The researcher initially numbered all organizations in each category on a piece of paper, then mixed these slips and picked one slip at a time. Based on Tensay and Singh's (2020) suggestion, this study took 30% of the total organizations, demonstrating a reasonable representation of the population. In the second phase, simple random sampling techniques are employed to select the respondents. The sample size of the study was 321.

Measurements of variables

Servant leadership was measured by a 14-item servant leadership scale developed by Ehrhart (2004). Van Dierendonck (2011) described this scale as a one-dimensional model of servant leadership. It is also employed by recent researchers in the public sector (e.g., Gnankob et al., 2022). Sample items for the servant leadership scale are: 1. My supervisor creates a sense of community among department employees. 2. My supervisor holds department employees to high ethical standards.

Organizational citizenship behavior was measured by 16 items developed by Lee and Allen (2002). Regarding this, Walumbwa et al. (2010) discussed that organizational citizenship behavior is best represented as a uni-dimensional measure. This scale has been employed by recent researchers in the public sector (e.g., Khattak & O’Connor, 2021; Khattak et al., 2022). Sample items for the OCB scale are: 1. I help others who have been absent. 2. I keep up with developments in the organization.

Perceptions of organizational politics were measured by a six-item scale developed by Hochwarter et al. (2003). Sample items for the perceptions of organizational politics scale are: 1. There is a lot of self-serving behavior going on in this organization. 2. People do what is best for them, not what is best for the organization. Political skill was measured using a six-item scale developed by Ahearn et al. (2004). Sample items for the political scale are: 1. I understand people well. 2. It is easy for me to develop a good rapport with most people. The measurements of perceptions of organizational politics and political skill were employed in the public sector by Kacmar et al., (2013). All items are measured using a Likert-type scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree.

Data analysis and results

The statistical tools employed for this study were SPSS and AMOS software version 26. AMOS is the most user-friendly of all the SEM software programs (Collier, 2020).

Preliminary Analysis

The study carried out preliminary analyses like managing missing data, outlier identification, multivariate assumption testing, e.t.c. These steps ensured the reliability of our data, allowing us to proceed with a robust analysis.

Missing Data Management

There are a number of methods for how handling the missing data: list-wise deletion, pairwise deletion, single imputation by mean substitution, single imputation by multiple regressions (Allison, 2002; Enders, 2010). Shafer and Graham (2002) mentioned that, if the number of missing values in variable screening is relatively small, the imputation method is recommended. In the present study, there were 12 missing values in variable screening. More precisely, SL-10, SL-13, OCB-5, and POP-5 have one missing value each. SL-8 and OCB-3 have two missing values each. And POP-1 has four missing values. At the end, all missing values were treated by employing the imputation (series mean) method.

Examination of Outliers

According to Hair et al. (2014), if the distribution is found to depart from normality, the researcher could assess the Mahalanobis distance to identify the potential outliers in the dataset. Structural equation modeling using AMOS computes the distance for every observation in the dataset from the centroid (Hair et al., 2014). The outlier occurs when the distance of certain observations is too far compared to the majority of other observations in a dataset (Hair et al., 2014). A good rule of thumb is that if the p1 and p2 values are less than 0.001, these are cases denoted as outliers (Collier, 2020). Therefore, out of 328 data points, the p1 and p2 values of seven (7) observations were less than 0.001, so they were removed from the dataset. The new measurement model is re-specified using the cleaned dataset. Thus, 321 cases were ready for further statistical analysis. Memon et al. (2020) mentioned that a sample size of 250 and above is enough for data analysis programs in covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM).

Basic Assumptions of Multivariate Analysis Checks

Since the data analyses involve the use of a sample and not the population, the study must be concerned with meeting the assumptions of the statistical inference process that is the foundation for all multivariate statistical techniques (Hair et al., 2014). The most important assumptions, including normality, linearity, homoscedasticity, multicollinearity, and Autocorrelation were tested, and the results were within an acceptable threshold.

Common Method Bias

Since the data was gathered from one source, it might raise concerns about common method bias. Thus, to mitigate such issues, this study utilized Podsakoff et al.’s (2012) suggestions of allowing the respondents’ answers to be confidential to avoid desirability bias. Moreover, the study also applied Harman’s one-factor analysis to check for common method bias.

Characteristics of respondents

The demographic profile data (n = 321) result indicated that the majority of the respondents are male, married, hold bachelor's degrees, and are experienced. Specifically, of the 321 respondents, 53.6% are male employees. The highest numbers of respondents’ ages were within the ranges of 31–40 years (38.3%). The next was within 41–50 years (29.3%). The third of them were within the 21–30 year age group (24%), and the rest of them were within the 51–60 year age group (8.4%). In terms of educational level, over half of them (54.8%) acquired undergraduate degrees. Those who obtained master’s degree status were 35.2%, and diplomas made up 10%. The highest number of employees regarding experience was between 6–10 years (28.7%), while the least were within 1–5 years (2.2%). Generally, the study can conclude that respondents are representative of the population in terms of gender, age, education, and experience.

Descriptive and Correlational analysis

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics and correlations among the study variables. This table reveals that the correlations between the research variables were in the expected direction. Servant leadership was positively correlated with organizational citizenship behavior (r = 0.75, p < 0.01) and negatively correlated with perceptions of organizational politics (r = -0.71, p < 0.01). Perceptions of organizational politics were negatively correlated with organizational citizenship behavior (r = -0.72, p < 0.05). Political skill was positively correlated with organizational citizenship behavior (r = 0.71, p < 0.01).

Evaluation of the Measurement Model

The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) technique was employed to assess the validity and reliability of each individual measurement scale. In the one-factor model, all variables were loaded onto a single latent factor, whereas in the five-factor model, each variable was loaded onto its respective latent factor based on the theoretical framework. Before analyzing the overall measurement model, it is necessary to run an independent CFA for each variable. Additionally, CFA examines the goodness-of-fit indices (Hair et al., 2014). Basically, to evaluate the measurement models, three categories of fitness are used: absolute, incremental, and parsimonious fit to ensure that reliability and validity could be achieved (Hair et al., 2014).

Evaluation of the Individual Measurement Model

Individual Measurement Model for Servant Leadership (Fig. 2)

To evaluate the individual measurement model for servant leadership, previous studies (Gnankob et al., 2022; Khattak et al., 2022; Liden et al., 2014; Miao et al., 2014; Shim & Park, 2019; van Dierendonck & Nuijten, 2011) stated that servant leadership is considered the first-order factor. CFA was computed using AMOS to test the measurement model, and the individual measurement model fit for servant leadership was CMIN/df = 7.879, CFI = 0.882, TLI = 0.861, and RMSEA = 0.147. According to Collier (2020), model fit improvement can be conducted to yield a good fit. Therefore, model fit improvement was conducted in the present study. The first improvement was that three items (i.e., SL-1, SL-5, and SL-6) from the indicators of servant leadership were removed due to low factor loadings (< 0.70). According to Hair et al. (2010), factor loadings greater than 0.70 are better to explain unobserved constructs in the study. The second improvement was that modification indices were checked and error terms were correlated. Hereafter, the individual measurement model for servant leadership yielded a good fit for the data: CMIN/df = 2.583, CFI = 0.937, TLI = 0.932, SRMR = 0.035, RMSEA = 0.070.

Individual Measurement Model for Organizational Citizenship Behavior (Fig. 3)

To evaluate individual measurement models for organizational citizenship behavior, Hameed Al-Ali et al. (2019) and Walumbwa et al. (2010) argued that organizational citizenship behavior is considered the first-order factor. The individual measurement model fit for organizational citizenship behavior was CMIN/df = 5.739, CFI = 0.927, TLI = 0.916, and RMSEA = 0.122. Model fit improvement was conducted. Two (2) indicators (i.e., OCBI-3 and OCBO-3) from the OCB were removed due to low factor loadings (< 0.70). Furthermore, modification indices were checked and error terms were correlated. Hereafter, the individual measurement model for organizational citizenship behavior yielded a good fit for the data: CMIN/df = 2.549, CFI = 0.985, TLI = 0.978, SRMR = 0.017, and RMSEA = 0.070.

Individual Measurement Model for Perceptions of Organizational Politics (Fig. 4)

Previous studies (Crawford et al., 2019; Hochwarter et al., 2003; Islam et al., 2013; Kacmar et al., 2013) argued that perceptions of organizational politics were considered the first-order factor. The individual measurement model fit for POP was CMIN/df = 12.471, CFI = 0.947, TLI = 0.912, and RMSEA = 0.189. Model fit improvement was conducted through modification indices, and error terms were correlated. Hereafter, the individual measurement model for perceptions of organizational politics yielded a good fit for the data: CMIN/df = 1.091, CFI = 0.999, TLI = 0.999, SRMR = 0.008, and RMSEA = 0.017.

Individual Measurement Model for Political Skill (Fig. 5)

Previous researchers (e.g., Crawford et al., 2019; Kacmar et al., 2013) argued that political skill was considered the first-order factor. The result revealed that CMIN/df = 12.448, CFI = 0.956, TLI = 0.926, and RMSEA = 0.189. Model fit improvement was conducted through modification indices, and error terms were correlated. Hereafter, the individual measurement model fit for political skill yielded CMIN/df = 3.678, CFI = 0.999, TLI = 0.982, SRMR = 0.008, and RMSEA = 0.093.

To assess convergent validity, factor loading, average variance extraction, and composite reliability were considered (Collier, 2020; Hair et al., 2014). The acclaimed values for factor loading are supposed to be greater than 0.70, for AVE at least 0.5, and for CR greater than 0.7 (Collier, 2020; Hair et al., 2014). Thus, the CFA result of each construct is presented in Table 2, which displays that the factor loading of each indicator is beyond the threshold. Moreover, the AVE of each variable was above 0.5, and that of CR was greater than 0.7.

Evaluation of the Overall Measurement Model

The overall measurement model involves combining and analyzing the relationships between the constructs to assess the overall model fit. The four-factor model (servant leadership, organizational citizenship behavior, perceptions of organizational politics, and political skill) yielded a good fit for the data: CMIN/df = 1.798, CFI = 0.970, TLI = 0.966, SRMR = 0.024, and RMSEA = 0.050, which is consistent with the fit indices of Hair et al. (2014).

The second objective of the measurement model is to test discriminant validity. To verify the discriminant validity, an overall CFA was conducted by combining the four constructs together (servant leadership, OCB, POP, and political skill). The result shows that the discriminant validity (covariances) between constructs is below 0.85 (see Fig. 6). A general guideline is that discriminant validity can be established when covariance is below 0.85 (Hair et al., 2014).

Evaluation of the Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

The structural model refers to the part of the model that represents the hypothesized relationships among the latent variables (Hair et al., 2014). It focuses on examining the direct and indirect effects of variables on each other (Hair et al., 2014). By utilizing the structural model generated through AMOS, researchers can gain insights into the complex relationships among study variables and assess the model (Byrne, 2016). A good model fit is accepted if the value of the CMIN/df is < 5, the model's overall goodness of fit; TLI and CFI > 0.90 (Hair et al., 2014; Hu & Bentler, 1998). In addition, an adequate fitting model is accepted if the value of the SRMR and RMSEA is < 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1998). Based on this, the study demonstrated a well-fitting model for the data, as indicated by several fit indices: CMIN/df = 2.672, CFI = 0.916, TLI = 0.911, SRMR = 0.068, and RMSEA = 0.072. These indices suggest that the data align reasonably well with the theory, indicating an acceptable level of fit for a structural model.

This section also focuses on hypothesis testing, which aims to determine the support or rejection of the proposed hypotheses. Hypothesis testing is a critical step in the research process, as it allows researchers to draw meaningful conclusions based on the collected data and evaluate the validity of their theoretical assumptions (Martin and Bridgmon, 2012). Through rigorous statistical analyses, such as direct, mediation (indirect), moderation (interaction), and moderated mediation (conditional indirect) effects, the study examines the links between variables and assesses the significance and strength of these effects.

Hypothesis 1: Servant Leadership has a positive effect on Organizational Citizenship Behavior

The study assessed the effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior. The results, as portrayed in Table 3 and Fig. 7, indicated that the effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior was positive and significant (β = 0.76; t = 15.01; p < 0.05). The squared multiple correlation (R2) was 0.58 (see: Table 3 and Fig. 7), this shows that 58% of the variance in organizational citizenship behavior is accounted for by servant leadership. Thus, servant leadership is regarded as one of the significant antecedents of organizational citizenship behavior in public service organizations.

Hypothesis 2: Servant Leadership has a negative effect on Perceptions of Organizational Politics

The study assessed the effect of servant leadership on perceptions of organizational politics. The results as portrayed in Table 4 indicated that the effect of servant leadership on perceptions of organizational politics was negative and significant (β = -72; t = -13.478; p < 0.05), supporting hypothesis 2. The R2 was 0.52, which shows that 52% of the variance in perceptions of organizational politics is accounted for by servant leadership (see Table 4 and Fig. 8).

Hypothesis-3: Perceptions of Organizational Politics has negative effect on Organizational Citizenship Behavior

The study assessed the effect of perceptions of organizational politics on organizational citizenship behavior. The results as portrayed in Table 5 indicated that the effect of perceptions of organizational politics on organizational citizenship behavior was negative and significant (β = -0.74; t = -15.42; p < 0.05), supporting hypothesis 3. The R2 was 0.54 (see Table 5 and Fig. 9), this shows that 54% of the variance in organizational citizenship behavior is accounted for by perceptions of organizational politics.

Hypothesis 4: Perceptions of Organizational Politics have a mediating role between Servant Leadership and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

The study assessed the mediating role of perceptions of organizational politics between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior. The results revealed that the mediation effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior through perception of organizational politics was significant (β = 0.28, p < 0.05, 0.05% CI = 0.26, 95% CI = 0.54), supporting Hypothesis 4. This indicates that perceptions of organizational politics competitively partially mediated the effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior. Competitively mediated means the perception of organizational politics has a negative role. The R2 was 0.66 (see: Table 6 and Fig. 10); this displays that 66% of the variance in organizational citizenship behavior is accounted for by servant leadership and perceptions of organizational politics.

Hypothesis 5: Political Skill has a moderating role between Perceptions of Organizational Politics and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

The present study examined the moderation role of political skill between perceptions of organizational politics and organizational citizenship behavior. There are three different ways that moderation can be assessed in a full structural model. These three ways are (1) the mixed model method, (2) the full indicator interaction method, and (3) the matched-pairs method (Collier, 2020). Collier stated that the mixed model method and the full indicator interaction method have their own drawbacks. The full indicator interaction method can lead to complex models and this complexity can make model estimation and interpretation more challenging (Collier, 2020). Moreover, Collier stated that the full indicator interaction method reduced model parsimony, making it harder to achieve a good model fit and potentially increasing the risk of over fitting the data. The mixed model method accounts for the measurement error in the independent and dependent variables but fails to run a latent interaction test and, subsequently, does not account for measurement error in the moderator (Collier, 2020). Collier stated that the recommended approach to conducting moderation testing is the matched-pair method. Therefore, the present study employed the matched-pair technique to assess the moderation. In testing moderation with a continuous variable, it is essential to form a mean-centered interaction term that is a product of the moderator and independent variable, as suggested by Collier (2020). Therefore, the study conducted a mean-centered interaction term for the political skill and perception of organizational politics in SPSS software.

The study result revealed a negative and significant moderating effect of political skill between perception of organizational politics and organizational citizenship behavior (β = -0.08, t = -2.06, p < 0.05) (see Table 7 and Fig. 11), supporting Hypothesis 5. The R2 value for organizational citizenship behavior was 0.61 (see Table 7 and Fig. 11). This finding revealed that 61% of the variance in organizational citizenship behavior is accounted for by perceptions of organizational politics, political skill, and the interaction of these two constructs. Without the inclusion of the moderating effect (perception of organizational politics → organizational citizenship behavior), the R-square value for organizational citizenship behavior was 0.54. This shows an increase of 7% in variance explained in the dependent variable (organizational citizenship behavior) when we compare with the inclusion of the moderating effect.

The results of the slope analysis conducted to better understand the nature of the moderating effects are shown in Fig. 11. As can be seen in Fig. 11, the line is much steeper for high political skill; this shows that at high levels of political skill, the effect of perception of organizational politics on organizational citizenship behavior is much weaker in comparison to low political skill. As shown in Fig. 11, as the level of political skill increased, the strength of the effect between perceptions of organizational politics and organizational citizenship decreased. It means employees having high political skills can manage their activities in the political environment and perform their organizational citizenship behaviors (Fig. 12).

Hypothesis 6: Political Skill has a Moderating Role in the Indirect Effect of Servant Leadership and Organizational Citizenship Behavior through Perceptions of Organizational Politics

Utilizing the AMOS software, the moderated mediation effect (conditional indirect effect) of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior through perceived organizational politics, moderated by political skill, was examined. To explore the conditional indirect effect, the analysis considered the levels of political skill at one standard deviation above and below the mean. By conducting separate analyses for these different levels, it is possible to assess how the conditional indirect effect varies based on the degree of political skill. The index value of moderated mediation was also considered. The index of moderated mediation is a statistical value that quantifies the strength and significance of the interaction effect between the moderator (in this case, political skill) and the indirect effect (Hayes, 2015a). By calculating this index, it is possible to assess the magnitude and significance of the conditional indirect effect across different levels of political skill. Based on this, Table 8 reveals that when the moderator is low (political skill at one standard deviation below), the indirect effect is significant (β = 0.28, p < 0.05, 0.05% CI = 0.366, 95% CI = 0.722). However, when the moderator is high (political skill at one standard deviation above), the indirect effect is not significant (β = 0.306, p > 0.05, 0.05% CI = -0.079, 95% CI = 0.571). Likewise, the index value of moderated mediation was not significant (index = -0.03, P > 0.05, 0.05% CI = -0.082, 95% CI = 0.073).

The R2 value for organizational citizenship behavior was 0.60 (see Fig. 12). This finding revealed that 60% of the variance in organizational citizenship behavior is accounted for by servant leadership, perception of organizational politics, political skill, and the interaction of perception of organizational politics, and political skill. Thus, servant leadership, perception of organizational politics and political skill are regarded as significant antecedents of organizational citizenship behavior in public service organizations (Fig. 13).

Discussion

The study examined the moderating role of political skill in the indirect effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior through perceptions of organizational politics. To study the moderated mediation model, the effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior was examined at the first stage. The result shows that servant leadership has a significant effect on the subordinate’s organizational citizenship behavior in the federal public service organizations in Ethiopia. This finding is consistent with earlier studies (Elche et al., 2020; Khattak et al., 2022; Mahembe & Engelbrecht, 2014), indicating that servant leaders are generally positively accepted by their subordinates, which ultimately transforms into higher organizational citizenship behavior. According to the study, those who advocate for public service organizations' policies should be concerned about whether or not their leaders are servants if they want to encourage the employees to exhibit citizenship behaviors. Simply put, those in positions of leadership in the public sector should encourage setting an example for others to follow.

The second stage was to examine the effect of servant leadership on subordinates’ perceptions of organizational politics. The result revealed that servant leadership has a negative effect on subordinates’ perceptions of organizational politics. This finding supports previous studies (Khattak & O’Connor, 2021; Khattak et al., 2022). The negative effect between perceptions of organizational politics and servant leadership suggests that servant leadership influences how employees perceive justice and equity. Employee views of organizational politics therefore grew as a result of leaders' failure to act in a servant-like manner. In other words, leaders who exhibit servant conduct increase the likelihood that their followers will do the same and lessen the likelihood that they will see organizational politics.

The third stage was to examine the effect of perceptions of organizational politics on organizational citizenship behavior. It was found that perceptions of organizational politics have a negative effect on organizational citizenship behavior. This finding is consistent with previous research (Atta Mohsin & Muhammad Jahanzeb Khan, 2016; Khan et al., 2019; Tripathi et al., 2023). The negative finding implies that if employees perceive more self-serving behavior from others, they will not be motivated to engage in organizational citizenship behavior. The current research's findings are likewise in line with those of Organ (1988), who proposed that an employee will be eager to enhance his or her organizational citizenship behavior so long as they perceive the organization is administered fairly (Vigoda-Gadot, 2007). In contrast, high levels of perceptions of organizational politics negatively affect the level of organizational citizenship behavior (Khan et al., 2019).

The fourth stage was to examine the mediating effect of perceptions of organizational politics between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior. The study found that the effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior has not only a direct effect but also an additional mediating effect. In the present study, perceptions of organizational politics are competitively partially mediated the effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior. This means that servant leaders have the ability to decrease the perception of politics by placing emphasis on treating their followers with fairness and ethics (Khattak et al., 2022). When employees perceive their work environment as less political, it increases the likelihood of them actively participating in organizational citizenship behavior (Islam et al., 2013; Kacmar et al., 2013; Vigoda-Gadot, 2007).

The findings of the study support previous studies conducted by Ehrhart (2004) and Qiu and Dooley (2022), who claimed that there is a mediated rather than direct link between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior. However, Ehrhart (2004) and Qiu and Dooley (2022) suggested organizational justice as a mediator in this link, and the present study emphasizes organizational politics as playing a similar role. In relation to this, scholars have claimed that, though organizational politics and organizational justice are distinct concepts, they are similar since they both aim to represent how employees view fairness and justice in the workplace (Andrews & Kacmar, 2001; Byrne, 2005; Kaya et al., 2016; Mathur et al., 2013; Vigoda-Gadot, 2007). Organizational politics refers to the use of power to achieve personal goals rather than organizational goals (Vigoda & Cohen, 2002). Employees who perceive high levels of organizational politics may believe that decisions are being made based on personal interests or favoritism rather than objective criteria (Vigoda-Gadot, 2007). This can lead to a sense of unfairness or injustice among employees who feel that they are being treated unfairly or that their contributions are not recognized or valued (Hochwarter et al., 2020; Kaya et al., 2016). Similarly, organizational justice refers to employees' beliefs about the fairness of the procedures and outcomes in the workplace (Ehrhart, 2004). Employees who perceive high levels of organizational justice believe that decisions are being made fairly and that they are being treated equitably. This can lead to a sense of fairness and justice among employees who feel that they are being treated fairly and that their contributions are being recognized and valued (Byrne, 2005; Mathur et al., 2013). For this reason, scholars have argued that the ideas of organizational politics and organizational justice are similar since they both aim to represent how employees perceive fairness and justice at work.

The fifth stage was to examine the moderating role of political skill between perceptions of organizational politics and organizational citizenship behavior, and the result showed that political skill can moderate the link. This study supports the Tripathi et al. (2023) study. According to Mintzberg (1985) organizations are political arenas, and political skill is necessary to thrive in these settings. Mintzber (1985), also pointed out that to succeed in the organization, in addition to leaders, general employees should also use political skills for work. If organizations truly are political arenas and inherently social in nature, then employees need social effectiveness skills like political skills in order to successfully interact with and influence others. Moreover, Kacmar et al. (2013) stated that politically skilled individuals do not view political work environments in a negative light but rather as an environment to be managed through the use of political skill. Overall, employees' political skills can play an important role in mitigating the negative effects of perceptions of organizational politics on organizational citizenship behavior.

The last stage was to examine the moderated mediation effect; however, the finding revealed that the index value of the moderated mediation was not significant. In relation to this, Cheah et al. (2021) stated that researchers are theory-driven, not data-driven, in their research design, especially when testing a hypothesized research model. Just to remind the study theory driven, the current study integrated the mediation model with the moderation model to examine the moderated mediation model. Because, moderated mediation is a framework that integrates mediation and moderation analyses to examine how mediated relationships vary as a function of context, boundaries, or individual differences (Cheah et al., 2021). Integrating the logic associated with the mediation model and moderation model produces a moderated-mediation framework in which perceptions of organizational politics are posited to mediate the effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior, and political skill moderates the effect of perceptions of organizational politics on organizational citizenship behavior. In other words, the study proposes that the strength of the mediating effect of perceptions of organizational politics on the nexus between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior will be stronger for employees with lower levels of political skill and weaker for employees with higher levels of political skill. Although the present researcher employed appropriate theory-driven methods, the moderated mediation effect was not significant, and as a result, Hypothesis 6 was rejected.

Conclusion

Based on the significance of the public service organization to national performance, an intentional effort was made in this study to show empirical evidence of how servant leadership could positively impact the subordinate’s organizational citizenship behavior but also minimize the negativities of political perceptions within the organizational environment. Also, it tried to reveal the usefulness of a subordinate’s political skills as a means of neutralizing negative outcomes from POP. The results of the correlation between servant leadership, organizational citizenship behavior, perceptions of organizational politics, and political skill showed strong relationships. This implies that servant leadership, organizational citizenship behavior, perceptions of organizational politics, and political skill share many attributes in common, and an increase in performance of one of them may add value to an increment of another. The study also revealed that the direct effects, mediation effect (indirect effect), and moderation effect (interaction effect) were found to be significant. From this result, one may infer that as leaders of public service organizations apply servant leadership in their day-to-day leadership practices, it helps to improve subordinate organizational citizenship behavior by reducing perceptions of organizational politics.

Implications

Theoretical implications

This study contributes to the literature on perceived organizational politics by demonstrating its mediating role in the relationship between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior. Previous studies have shown the links between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior, but, to the best knowledge of the current researcher, no study so far is known about the mediation mechanisms of perceptions of organizational politics. This is the first study conducted on the effect of servant leadership style on subordinate’s organizational citizenship behavior and the mediating role of perceptions of organizational politics using Ethiopian public service organizations and within the Ethiopian cultural settings. The study found that perceptions of organizational politics are one mechanism to explain the effects of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior.

Practical Implications

Public service organizations can take the following steps to promote organizational citizenship behavior and create a positive work environment that helps to improve organizational effectiveness: Firstly, public service organizations should apply servant leadership principles. Through putting their employees' needs first and modeling qualities like humility, empathy, and empowerment, leaders can serve as role models for employees. Employee trust, respect, and teamwork might result from this, which can improve organizational citizenship behavior. Secondly, public service organizations should promote an environment of openness and fairness. They may lessen the perception of organizational politics by actively encouraging openness in decision-making procedures and making sure opportunities and resource distributions are fair. Employees may be more inclined to participate in organizational citizenship activities if they work in a setting where they are respected and feel trustworthy. Thirdly, public service organizations should establish mechanisms to recognize and reward organizational citizenship behavior. They should encourage employees to participate in organizational citizenship by recognizing employees who frequently display these behaviors. In order to properly identify organizational citizenship behavior, formal recognition programs, performance reviews, or other incentive systems might be put in place. Finally, public service organizations should actively support and foster a collaborative culture. By sharing knowledge, assisting others, and building positive relationships, employees can contribute to a supportive work environment that encourages organizational citizenship behavior.

Limitations and Future Research

Despite all the contributions and implications made by the research highlighted above, it also has some limitations. The first is the generalizability of the results; although the researcher tried to capture the maximum number of federal public service organizations operating in Ethiopia, only six were selected. Therefore, in the future, this research can be conducted at all federal public service organizations. Second, the current researcher collected data for the predictors and criterion variables from one source. Therefore, future researchers should collect data from different sources. Third, researchers should explore the impact of perceptions of organizational politics on organizational citizenship behavior and reduce the damaging aspects of organizational politics on organizational citizenship behavior by incorporating additional individual difference moderator variables. Social intelligence may play a moderating role. Social intelligence is one of the most important character strengths to determine, especially the success of employees in organizations, because organizations are social in nature (Garg, Jain, & Punia, 2020). The usefulness of social intelligence in response to perceptions of organizational politics is unknown. To the best of the present researchers’ knowledge, the moderated role of social intelligence between perceptions of organizational politics and organizational citizenship behavior has never been examined previously in any single study. Therefore, conducting studies on social intelligence as a moderator may reveal fresh and novel findings.

Summary