Abstract

Buchanan attempted to seek new theoretical construction through the contract method by introducing elements such as ‘individual’, ‘veil of uncertainty’, ‘public choice’, ‘decision costs’, and ‘unanimous agreement principle’. He not only transformed the contract theory model but also interpreted the ideas of consensus politics in an acceptable manner. Specifically, ‘individuals’ are entities of choice and behavior, and the process of choice allows individuals to express different goals and interests. The ‘veil of uncertainty’ prompts individuals to think about issues from a fair point of view when interests cannot be identified and future prospects are unpredictable and to make choices that are beneficial for both themselves and the group. ‘Public choice’ can solve the problem of justice diversity because it does not exclude different or conflicting motivations and goals. ‘Decision costs’ and ‘external costs’ both limit the way collective decisions are made and help identify the normal consequences of constitutional choices. The ‘unanimous agreement principle’ gives everyone equal status, allowing each person the right to pursue their own goals and values and preventing others from abusing their power. The use of the aforementioned theoretical elements not only helps people discuss constitutional choices at a general level but also helps to present the true face of the collective decision-making process, thereby establishing an empirical theory about the actual logic of individual actions in the political system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

In Chapter 13 of ‘Leviathan’, Hobbes pessimistically describes the human condition in its natural state. In this state, knowledge of geography, timekeeping, art, literature, society, and more would not exist. Worst of all, people would constantly live in fear and danger of experiencing a violent death, and their lives would be lonely, impoverished, degraded, cruel, and short (Hobbes, 1985, p. 95). In the dichotomy between nature and society, Hobbes tries to tell readers that this natural state is harsh, barbaric, and fleeting, and only by establishing a state can everyone live better lives. To escape the natural state, which is rife with the risks of total war, Hobbes’ social contract theory advocates that all individuals must surrender their natural rights to the sovereign, who is elected by the public and has the right to establish and enforce laws without being bound by the contract. While this approach does bring peace to human society, the Hobbesian contract only transforms universal fear into a specific fear, and it does not explain why individuals have a moral obligation to obey the sovereign, making it not a true contract (McLellan, 2003, p. 250).

Buchanan inherited Hobbes’ conception of the social contract, but unlike Hobbes’ pessimistic predictions, he believed that the vast majority of people were unwilling to be coerced from the outside and were actually capable of managing themselves and that harmony between pure individualism and the political order of the public interest could be achieved. Buchanan’s constitutional contract is not intended to emulate Rawls’ fair law of social establishment of certain rules but rather to explore constitutional choices at a general level and to examine the extent to which people can rationally discuss standards for social change if no one’s values are placed higher than anyone else’s. The issues discussed in the constitutional process include the following: What rules can enable people to live together better? How can we maintain the freedom of independent individuals while living in a peaceful, prosperous, and harmonious environment and create our own values? Apart from factors such as ‘God’s will’, ‘historical tradition’, and ‘natural rights’, how is the order of a society formed, and what is its legitimacy based on (Vanberg, 2020)?

An overview of Buchanan’s constitutional contract ideology

In Buchanan’s analysis, the marginal cost and benefit of producing, protecting, and stealing goods were equal, and if all parties could reach a consensus on disarmament, everyone’s lives would improve due to the reduction in the cost of investing in the protection and plundering of goods. However, even though everyone was strongly willing to sign a ‘cease-fire agreement’, they also realized that this agreement could be torn up at any time. As a result, everyone found themselves trapped in a prisoner’s dilemma (Voigt, 1997). As the theoretical starting point of the Buchanan Constitution, the ‘N-person prisoner’s dilemma’ differs from theoretical frameworks characterized by ‘force’ and ‘plunder’. It attempts to provide people with an opportunity to think and create a better society. People are placed behind the idealized ‘veil of uncertainty’, and through negotiation, exchange, and compromise with each other, they explore which rules can obtain public consensus and then collectively examine which rules are the best (Besley, 2007). According to Buchanan’s perspective, although predatory behavior cannot be completely eliminated in real-life situations, consensus-based political structures still have realistic expectations. This is because collective action not only eliminates some of the external costs imposed by individual behavior but also provides a means for external benefits that purely individual behavior cannot foresee and encourages individuals to consider long-term benefits. Moreover, collective commitment is also a mechanism for overcoming individual short-term weak willpower. When members of society become aware of their own weaknesses, they will make precommitments through appropriate methods. Most members of society, including politicians, are also willing to constrain themselves through precommitments (Voigt, 1997). When people have an expectation of a cooperative model, if a social contract requires all members to collectively choose to provide and share the cost of pure public goods and pushes for unanimous agreement, and if each participant is clear that this agreement will benefit them—the benefits obtained will be greater than those provided by pure public goods—then people seem to be able to join a collective agreement voluntarily, which can be decided upon only unanimously. Buchanan concludes that social norms can be established through cooperative means.

Buchanan believes that the state is not a necessary evil but rather a mechanism that promotes collective action, allowing individuals to achieve things together that they cannot achieve alone. Specifically, in real-life, some people try to exert their power over others, but improving their own fate at the cost of sacrificing that of another may lead to a disadvantageous situation for both parties. The even more extreme pursuit of personal interests can lead to the whole society falling into a state of complete failure. Therefore, rules are needed to regulate people’s behavior and ensure that society strives to achieve positive and harmonious results (Vanberg, 2004). Otherwise, not only will personal freedom be harmed, but society will also fall into a chaotic situation of a ‘war of all against all’ (Rizzo and Dold, 2020). In this circumstance, after repeated games, people eventually realize that cooperative games are not only beneficial to themselves but also contribute to social stability. Therefore, in exchange for the benefits brought by the system, individuals voluntarily give up their own freedom, and those who have already given up their freedom expect others to do the same, as everyone prefers to live in a society of mutual respect. As a result, all individuals in the group gradually reach consensus, sign a common contract, establish a state, and follow common rules. In the book ‘The Limits of Liberty’, Buchanan describes in detail the process of constitutional order formation, which is divided into seven stages: (1) Hobbesian equilibrium; (2) the emergence of civil law; (3) a series of activities in the post-civil law phase, including trade and theft; (4) the development of political constitution; (5) a series of political activities in the post-constitutional stage, including voting, vote trading, and public goods production; (6) a constitutional review process; and (7) activities occurring during the review process, including legal activities related to review and perhaps constitutional amendments (Congleton, 2014). In Buchanan’s view, the first round of constitutional negotiations established Hobbesian principles of wealth and welfare distribution as a given, attempting to reduce losses from ongoing conflicts by allowing individuals to exercise complete control in clearly defined areas. This is Buchanan’s new theory on the origins of common law, which is considered a multiparty ‘cease-fire agreement’. Given the equilibrium that arises from contractual promises in civil law, Buchanan anticipates another round of constitutional negotiations happening over the type of political constitution analyzed in ‘The Calculus of Consent’. The reason contractual governments are widely accepted is that they aim, by systematically enforcing civil laws, to prevent regression into a state of anarchy. Individuals who are faced with uncertainty and risk also agree to limitations on their individual freedom in exchange for similar commitments from other members of the community. In addition to its law-enforcing function, this type of government can also solve public welfare and externalities problems. Although a contract-based government is a productive organization, it still needs to enforce political constitutions to limit collective actions within agreed-upon decision-making processes and public policy areas, which gives rise to the system of constitutional review.

Buchanan believed that the rule of law, freedom, stability, and a prosperous economic outlook are not inherent qualities of a society. Moreover, individuals may engage in conflicts due to their desires, and society may also descend into disorder due to conflicts. Therefore, human society needs to establish a set of norms governing the actions of people in their interactions with one another to prevent conflict and other unpredictable risks (Besley, 2007). When all participants agree that the outcomes resulting from accepting appropriate constraints are better than those resulting from refusing behavioral limitations and when everyone agrees to promote the procedures for collective action, the consequences of this universal promise exchange will eventually prove beneficial for everyone. The ‘leviathan’ is the goal sought by adopting Hobbes’ social contract, but for Buchanan, it is a synonym for out-of-control government. In ‘Power to Tax’, the leviathan is analyzed as a possible consequence of imperfect constitutional design, which allows the government’s taxing authority to be captured by a stable transfer-maximizing majority coalition, a budget-maximizing, poorly monitored Niskanen-type bureaucracy, or by a powerful self-interested political leader interested in expensive projects (Congleton, 2014). Regarding the analysis of modern government models, Buchanan asserts that the government models of most Western countries do not belong to either the ‘benevolent authoritarians’ or the ‘leviathan with independent interests’, but rather lie somewhere between the ‘leviathan model’ and the ‘democratic model’, Buchanan divides these models into two categories based on their differences in modern government functions: ‘protective’ and ‘productive’ (Buchanan, 1975a, 1975b, p. 88). The former mainly protects individuals’ property and freedom, while the latter mainly provides public goods for individuals. Regarding this, Buchanan suggests that the Constitution can appropriately limit a ‘protective state’ that aims to protect property rights and oversee rules, contracts, and infringement disputes, but he is skeptical of whether it has the ability to limit a ‘productive state’ (Brennan and Munger, 2014). Although Buchanan acknowledges the positive role of the government in improving individual welfare and promoting collective action, he also recognizes the need to limit government power to prevent it from becoming an oppressive ‘leviathan’ (Holcombe, 2020). To describe the potential risks of modern government, Buchanan draws an analogy between market transactions and politics. In his opinion, the non-individualized operation of the market has turned everyone’s decisions into marginal decisions. Market participants may not always be able to achieve their desired benefits through trading behavior because, for the entire market system, each individual has numerous readily available alternative trading objects. One person alone cannot dominate the market. However, political transactions do not have or have fewer such alternative choices. It is not easy for individual participants to renegotiate agreements and ultimately exit the ‘social contract’ and turn to other ‘public good sellers’. Therefore, compared to a government that actually controls large social resources and monopolizes the supply of public goods, individuals are obviously in a weak position.

Although Buchanan advocates for various measures to constrain the government, such as specifying election administration methods, voting rights, election timing, and procedures, voting rules, eligibility requirements, agency methods, and democratic processes, he has always believed that the defects manifested by governmental institutions are not necessary evils. Buchanan finds that past political research has always fantasized about reforming individual behavior by imposing moral constraints on private interests and emphasizing the concept of public welfare, and the emphasis was often on moral innovation rather than structural reform. Consequently, the collapse and malfunction of a particular system are often attributed to bad people rather than the rules that constrain them. In his view, the above theoretical claims have failed to explore various inefficiencies and their underlying causes in depth. In contrast, Buchanan’s constitutional proposal does not focus on correcting the flaws of the government but rather analyzes the imperfect constitutional system that may cause the government to lose control. He proposes that system design should focus on the true nature of human behavior, which means taking human imperfection as a fundamental constraint and designing systems that accommodate such imperfections as much as possible. What does it mean to design rules according to the true nature of human actors? Buchanan believes that we must reject metaphysical assumptions that political authorities are composed of moral superheroes in order to prevent false or arbitrary coercion from replacing independent thinking. Specifically, Buchanan opposes using benevolent agents to analyze government, as he believes that such an assumption not only denies the legitimacy of limiting government power but also poses two types of realistic dangers: one is allowing the state to enter all social domains, suffocating individual freedom; the other is enabling politicians to use public goods to satisfy their private purposes, leading to corruption (Dias, 2009). Additionally, Buchanan emphasizes the importance of injecting some realism into political behavior. He believes that all political processes are the outcomes of different motivations and interests of individual choices and actions and that government institutions composed of individuals will inevitably mix personal interests into government and government decisions. It is often assumed that government officials are wholeheartedly pursuing the public interest, but the true desires of some officials may only be about conquering and maintaining power. This can lead to state power becoming a means by which some people seek private gain, causing the public interest attributes that the government should have to be lost to partiality, narrowness, and untrustworthiness (Brennan and Buchanan, 2004a, 2004b, p. 101). From this, Buchanan concludes that ‘rulers’ who act as agents are essentially no different from ordinary citizens in pursuing their personal interests, and there are no more moral guarantees. The logic of constitutional constraints is contained in the following prediction: Any power granted to the government may be exercised in ways that differ from the desirable purposes defined by citizens under the ‘veil of ignorance’ in certain contexts and occasions.

To curb the spread of bureaucratic privilege and prevent the abuse of political procedures by the power structure to exploit people, Buchanan advocates for the invention of a new type of political technology and democratic representation that would prevent the government from engaging in rent-seeking and special interest activities and ultimately satisfy the interests of everyone (Vanberg, 2014). This new form of representation is based on a constitutional assertion of rule constraints. Buchanan believes that rules can help ensure balanced outcomes or result in patterns for a community composed of individuals with established abilities and goals. Conversely, if a society lacks rule constraints, producers or sellers of goods will inevitably attempt to seize property, force labor, engage in unfair competition, bribe officials, and engage in monopolistic operations and rent-seeking activities. Once ‘plunder’ becomes an acceptable economic strategy, people will decrease their investment in productive behavior and increase their investment in predatory behavior, as well as increase their offensive and defensive investments to prevent others from harming them (Wagner, 1987). Considering that the constitution provides the most important rules in society, the expected benefits it provides not only form a supportive framework for a broad range of economic and political activities but also encompasses the overall benefits that arise over time from sustained mutual interactions and cooperative processes being appropriately constrained (Vanberg, 2005).

Buchanan’s constitutional thought can be summarized as follows: ‘a series of pre-established rules within which subsequent behavior takes place’ (Brennan and Buchanan, 2004, p. 1). This ideology requires that all political action be carried out according to certain rules, and the binding force of these rules depends on whether and to what extent they conform to the meta-rules. In the above system of rules, some rules were agreed-upon by the actors during the constitutional stage, and they are called ‘consented rules’. Another set of rules, known as ‘just rules’, were not consented to but were derived from the ‘consented rules’ and therefore also have binding force. To express his constitutional proposals more accurately, Buchanan elaborated on the concept of justice and redefined the relationship between justice and rules. Generally, justice is seen as a standard for evaluating behavior and rules, but in Buchanan’s theory, rules are the basis of justice, and rules set conditions for justice, rather than the other way around. Therefore, Buchanan’s constitutional rule system includes two types of justice concepts: justice under the rules and justice between the rules. Justice under the rules refers to the fact that behavior cannot violate previously agreed-upon rules. The significance of rules lies in providing information about the behavior of others to each activity subject, thus allowing each subject to pursue their own goals based on the reasonable expectations of future behavior stipulated by the rules. The value of justice lies in adhering to rules. Interpreting justice from the perspective of adhering to rules is completely different from the following viewpoint: specific rules are valuable because they meet objective standards of justice; Justice between the rules involves the issue of making choices between different rules. Buchanan’s view is that judgments about what rules should be can only be made based on more abstract rules (i.e., meta-rules) that apply to making judgments between different rules. The statement is: as long as the selection process conforms to the accepted meta-rules, then the rules selected from it are justice. Under this system of rules, justice exhibits a particular ‘non-teleological’ and context-dependent nature. It can no longer be said that those completely universal, abstract, context-deficient concepts of justice dictate what people should do—whether it is regarding behaviors or the nature of rules. How to act in a just manner solely depends on the specific rules to which an individual happens to agree. And it should not be assumed that justice can provide an independent standard, thus constructing a completely new holistic ideal rule, only consensus can fulfill this fundamental normative function. This is the most profound logical relationship in Buchanan’s constitutional theory(Brennan and Buchanan, 2004a, 2004b). Therefore, Buchanan’s constitutionalism advocates a theoretical approach similar to Kelsen’s normativism. Compared with Kelsen’s pure legal theory system, Buchanan’s constitutional rules also embody a recursive characteristic; that is, the effectiveness of the post-constitutional rules is relative to the effectiveness of the constitutional rules, which are produced under the consistent agreement of the constitutional phase (Bertolini, 2019).

Analysis of the structure of Buchanan’s constitutional contract

The notion that ‘right’ takes precedence over ‘goodness’ indicates that the purpose of societal existence is not to enhance a particular form of ‘goodness’, such as welfare, virtue, or other specific forms of improvement, as the criteria for judging justice but to provide individuals with a framework that enables them to pursue their own goals. Buchanan further argued that a suboptimal notion of ‘right’ is inadequate and that accepting constitutional governance is a better choice. To support this claim, Buchanan placed individuals in a constitutional choice scenario to consider and discuss the basic rules of the social and political order. This theoretical approach is very similar to Rawls’ idea of the ‘veil of ignorance’, which is a theoretical hypothesis for how social members can form a consensus. Rawls assumes that the contracting parties in the original position when deciding on the basic principles of society, have no knowledge of their specific identity, social status, intelligence, physical abilities, income, wealth, specific psychological tendencies, or even unique values and ideals. Their choices are based solely on general common knowledge. The relevant assumption in the ‘Veil of ignorance’ is to eliminate any individual, relying on material, intellectual, and information advantages, and then using specific social arrangements to seek benefits for himself. In contrast, Buchanan’s constitutional contract requires only that the contracting parties adopt a position equivalent to that of the ‘veil of ignorance’ under the constitutional context (Rawls, 1988, p. 136), in which the constitutional context is more like a motivating mechanism that compels self-interested agents to think about rules from a fair perspective. When the context is given appropriate characteristics, constitutional choice becomes a purely procedural process, and individuals can autonomously establish rules according to their own preferences. The rules established through the unanimous agreement of all members have legitimacy and are not subject to any moral criticisms. Structurally, Buchanan’s constitutional contract mainly consists of five elements.

Status quo

According to Buchanan, we cannot understand the status quo narrowly as a particular time segment but rather as a set of existing rules and procedures (Melenovsky, 2019). In Buchanan’s constitutional contract, the status quo is the starting point for thinking about basic social rules and the object of discussion and improvement. If we want to identify existing problems in social structures and propose solutions, the status quo becomes a reference point for future institutional improvements. The status quo includes at least two meanings: first, the actual life status of each individual, including but not limited to their special identities, social status, intelligence, physical strength, income, wealth, psychological tendencies, and personal values, as well as the political system they are in; and second, the situation that individuals find themselves in when constitutionalism has been chosen. As the choices possible under constitutionalism are based on long-term collective behavior considerations, these include combinations of different time sequences and resource allocations. Therefore, individuals cannot predict their position in the expected chain of collective decisions, and there is no identifiable self-interest. As a result, selfish individuals and altruistic individuals are no longer distinguishable in their behavior.

Individual

Buchanan believes that the understanding of social interaction processes must be based on the analysis of individual behavior, as individuals are the only entities that make choices and have behaviors (Vanberg, 2020). As the object of behavioral analysis and the subject of value expression, individuals possess characteristics such as independence, cognition, morality, and creativity. First, each person is an independent individual with different goals and interests in collective action (Dias, 2009). If different individual interests are assumed to be the same, then the subject is eliminated, and there will be no organized activity.Footnote 1 Second, individuals possess a certain level of cognitive ability, including self-awareness and foresight. Individuals view themselves as one potential manifestation of existence and have the ability to imagine becoming a better version of themselves. In addition, individuals have the ability to rank and classify their foresight and can constrain themselves to achieve their future expectations. Third, individuals have a sense of morality, and the constitutional selection process tends to treat everyone as morally equal and allow everyone to receive equal respect, consideration, and, ultimately, treatment (Brennan and Munger, 2014). Therefore, individuals are not limited by any narrow, hedonistic, or self-interested assumptions in the constitutional contract, and each person establishes a coherent and subjectively meaningful morality. Politics thus becomes a process for individuals to pursue self-worth. Last, individuals possess reflexivity and creativity. Although the social environment plays a shaping role in an individual’s future preferences and imagined choices (Lewis and Dold, 2020), what individuals do is not just a passive reaction but rather is more importantly displayed through seeking and creating values. Individuals not only have the ability to evaluate the state of society but also have the capacity for introspection into their own character (Müller, 2002). Based on reflection, evaluation, and criticism, individuals can choose an effective set of standards to assess their lives and ultimately change the rules that describe the social value system.

Object

If constitutional contracts are mechanisms through which people express their interests and preferences, what rules are available for them to discuss and choose (Cardinale and Scazzieri, 2018, p. 283)? Buchanan first rejected natural law and natural rights theories and then positioned existing social rules as ‘relatively absolute absolutes’ .This suggests that proven values such as enlightenment, law, custom, and liberalism cannot be easily abandoned but can be challenged, even if this does not restrict the goals pursued by collective choice (Wagner, 2019, p. 50). Even modern democratic systems cannot be viewed as a predetermined outcome but rather as one of the options for constitutional choices. As advocated by Hayek, the construction of an ideal society should be placed within an appropriate legal framework, where rules provide general conditions rather than arbitrary interventions, so that individuals can pursue their own goals individually or collectively and ultimately indirectly realize a ‘better society’ (Vanberg, 2005). Similarly, Buchanan does not presume to speculate on what individuals may agree upon, as such agreements may change through subsequent contracts. His constitutional contract aims to create an environment where individuals can construct their ‘artifacts’ through their own creativity and openness, ultimately changing the basic rules of social order and progressing toward a vision of a better society (Buchanan and Vanberg, 2002).

Choice

The significance of choice lies in allowing individuals to become responsible for their actions through freedom of choice. As a conscious behavior, the essence of choice inevitably opposes any predetermined view. If individuals are bound by a completely deterministic world, then there is no choice to speak of (Wagner, 2019, p. 653). Furthermore, choice must also be independent of all external preferences and prior values. If an individual’s choice is defined as either correct or incorrect by certain moral standards (Lewis and Dold, 2020), then the meaning of choice no longer exists. Only by breaking away from external preferences and restrictions can individuals make choices and replace the predictability of behavior with uncertainty (Lewis and Dold, 2020). Buchanan’s perspective on unrestricted choice is that it enables individuals to distance themselves from existing values or rules in order to examine different lifestyles and moral views, which can help individuals actively reflect and establish their own evaluation standards. Similarly, constitutional choice ensures that everyone can design a constitution that meets their expectations without being limited by agreements reached by unspecified groups or requiring the implicit power to monopolize the definition of legitimate behavior (Kliemt, 1994). People can choose both the rules and the choices based on their actual situation.

Unanimous agreement

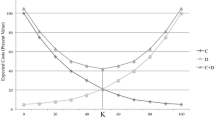

Buchanan’s constitutional contract also inherits Knut Wicksell’s principle of unanimous agreement, which includes the following four aspects. First, ‘agreement’ refers to a consensus reached by a group of rational individuals. Second, ‘agreement’ must be based on the individual, voluntary balancing of interests, and the utility between individuals cannot be compared. Third, ‘agreement’ must be unanimous. Finally, if the cost of unanimous agreement is too high, the majority rule may be adopted, but the level of agreement should be maximized. The first three conditions require that any collective decision must obtain the unanimous consent of all participants, and consensus is a legitimate standard for considering agreement. This embodies the concept of ‘respecting every person’ and ‘not harming anyone’s freedom’, which is equivalent to the moral principle that ‘no one can simply treat another person as a means to an end’ (Kliemt, 1994). Knut Wicksell was the first to recognize the significance of the ‘principle of unanimous agreement’ as an ideal standard, as it is necessary to ensure that public behavior truly improves or at least does not harm everyone’s situation. Buchanan, on the other hand, uses the ‘principle of unanimous agreement’ as the sole standard for judging rules (Buchanan, 2002, p. 59), with the method of judgment being whether the legal system is consistent with the potential content of a social contract between all participants. From the fourth condition, considering the impact of narrow self-interest on negotiations and the actual decision costs, Buchanan states that democratic politics can adopt majority decision-making rules without necessarily choosing unanimous agreement, but he also emphasizes that majority decision-making rules should be derived from consensual contractual logic. To make the ‘principle of unanimous agreement’ operational, Buchanan divides decisions into different levels, and in areas where the impact on individual life is greater, such as basic human rights and property rights, he believes that a larger proportion of majority agreement, or even unanimous agreement, is needed.

Buchanan and Rawls both focus on seeking just rules for social cooperation and while their theories share some similar elements, they also have some crucial differences (Dold, 2018). Compared to Rawlsian ideas, the ‘veil of ignorance’ is a more idealized theoretical construct, as people living in the real world and knowing who they are can no longer make choices behind the veil of ignorance. The conditions in Buchanan’s constitutional contract are relatively loose, and what drives individuals to make constitutional choices is uncertainty rather than ignorance. It allows individuals to independently weigh and pursue their own interests, and they are influenced by the constitutional choice situation and have to adopt strategies similar to the ‘veil of ignorance’, choosing rules that can eliminate or minimize potential disasters. In addition, Buchanan’s use of public choice theory makes the constitutional choice process more rigorous and rational. Specifically, individual actions are distinguished from collective actions, and the choice process allows individuals with differing objectives to express their values. The ‘N-person prisoner’s dilemma’ creates the potential for cooperation between individuals in a game of strategy. The ‘veil of uncertainty’ encourages individuals to approach issues with a sense of fairness when interests are ambiguous and future outcomes are unpredictable and guides individuals to choose rules that are beneficial to both themselves and the group. External costs and decision costs limit the ways in which collective decisions are made. The unanimous agreement principle gives everyone an equal advantage, allowing individuals to pursue their own goals, objectives, or values, as well as the right to decide what will happen in the real world while preventing abuse of political power that might disrupt people’s lives (Kliemt, 1994). In summary, the combined effect of these elements gives Buchanan’s constitutional contracts a relatively broad empirical foundation.

The role of the contractual model in Buchanan’s constitutional theory

Buchanan believes that the analytical framework for the above problems must be a contractual model. He clearly expresses this view in ‘The Calculus of Consent’, stating that the contract model opens up space for the discussion of fundamental social issues, placing individuals in an ideal position to discuss and analyze the possible standards for changing power structures, relationships between individuals and between individuals and governments, and the legitimacy of a country’s mode of operation (Vanberg, 2014). This contractual method maintains coherence in both form and content and is not only a way of making a contract but also a result of the agreement, in which the decision-making process is full of complex calculations and choices. In addition, the contract theory method exhibits two aspects: first, it discusses the choice of constitutional rules at a general level; second, the discussion or theoretical construction of the relevant system is empirical. Its purpose is to implicitly rationalize political structures that have never had a strict theoretical foundation and to provide some theoretical certainty for ‘individualistic democracy’ (Buchanan and Tullock, 2000, p. 328). Specifically, the role of the contract mode in Buchanan’s constitutional theory is as follows.

Organizing individuals

Buchanan’s constitutional theory contains two opposing logics: the first involves transforming the logic of collective organization into individual calculation, emphasizing that we should understand all social interactions by analyzing the behavior of participants and acknowledging that individuals are the ultimate and only entities that can make choices and take action. The second involves transforming individual choice into collective decision-making, emphasizing how independent individuals seek their own goals and values and cooperate with others to seek collective goals, as well as how to determine what will happen in the real world. Obviously, in the transformation of the second logic, the contractual method becomes the bridge that connects individual calculations and group decisions (Buchanan, 1975a, 1975b). In fact, the constitutional contract is also a theoretical link between Buchanan’s public choice theory and constitutional economics. The significance of the contract method is not only that it is a mechanism for translating individual choice into collective decision-making, but more importantly, it establishes the logical foundation for relevant social norms through individual choice rather than from assumed external ethical standards (Brennan and Buchanan, 2004a, 2004b, p. 228).

The foundation of nation-building theory

How can individuals who pursue self-interest be organized to establish a country and abide by laws? As mentioned earlier, Hobbes’ solution is to sacrifice individual rights in exchange for the existence of civilized order, but Buchanan explicitly opposes any form of external coercion. He believes that politics is a complex process of transactions in which individuals seek collective goals that cannot be pursued by any genuinely effective non-collective or private means. To achieve these goals, individuals, who are governed by potential social order, must either provide funds for public goods for common consumption or exchange behavioral promises with each other so that all participants can share certain benefits together (Müller, 2002). Through the principle of reciprocity, individuals agree to limit their own behavior as a cost and expect that the behavior of others with whom they interact is similarly restricted in order to pursue expected benefits (Cardinale and Scazzieri, 2018, p. 273). Thus, people establish states and follow common rules (Buchanan, 1975a, 1975b). Unlike the predatory political paradigm, Buchanan’s constitutional contract creates an endogenous paradigm for political order through the public choice mechanism, where government and legal institutions are not external entities that regulate society members but rather the result of collective interactions between individuals (Holcombe, 2020).

Fair incentive mechanisms

Buchanan believes that politics should not be viewed as a struggle for power or control and that political rules should not be determined by who can exert power over others to seize their resources, ultimately maximizing personal gain. Such political paradigms effectively continue the wars of human society in another way (Meadowcroft, 2016). Unlike those political views that purely manifest conflict, struggle, and exploitation, Buchanan advocates a political paradigm based on consensus. This political view opposes coercion, emphasizes individual freedom of will as a precondition, and acknowledges that people establish relationships with each other on an equal footing and ultimately share government and politics in broader communication. As a mechanism for the realization of consensus-based politics, the constitutional contract makes participants show uncertainty about their own constitutional interests and a relative lack of constitutional knowledge through specific situational design, and because of the filtering role played by the ‘veil of uncertainty’, this situation not only increases the possibility of people reaching an agreement on a set of rules in line with their common interests but also prompts self-interested agents to choose the principle of impartiality to judge the rules. Therefore, the essence of Buchanan’s constitutional contract is not about what rules can be recognized as being of mutual interest but rather about which procedure is most likely to form mutual interest rules and be jointly accepted by all parties among all alternative procedures (Vanberg, 2005).

Mechanism of value generation

Buchanan’s contract theory aims to establish an order where everyone can enjoy specific purposes, goals, and values without allowing any value to overpower others (Bertolini, 2019). Under this strict contract paradigm, the entire political process becomes a complex, multiparty contract system where equally positioned individuals achieve their common goals through freely choosing and communicating with each other. Therefore, the constitutional contract becomes an important means for people to express their individual interests and values, which is integrated with Buchanan’s assertion that ‘the individual is the only existing value expresser.’ Buchanan believes that individualism provides a better standard than those a priori ideas. If a situation is judged to be ‘good’, it only needs to be considered whether that situation allows individuals to get what they want, regardless of what they are (Vanberg, 2020). In other words, the effectiveness of rules depends not on whether they comply with efficiency or other special values but only on whether they are actually accepted by the participants. Therefore, Buchanan’s constitutional contract not only ensures that individuals are protected from the individual and collective actions of others but also protects the right of individuals as independent entities to freedom and the ability to create value (Kliemt, 1994).

Criteria for institutional evaluation

As previously mentioned, constitutional choices can enable people to discuss and analyze possible standards for changing the structure of rights, interpret and understand the relationship between individuals and between individuals and the government, and evaluate the legitimacy of the operation of the state (Vanberg, 2014). Therefore, what are the appropriate standards for evaluating public institutions and rules? Knut Wicksell emphasizes the significance of the principle of unanimous agreement as an ideal criterion, which means that government action truly improves the situation for everyone, or at least does not cause harm. Later, Buchanan also accepts these ideas, emphasizing that political economy should not only examine whether everyone’s situation has improved but should also use everyone’s unanimous agreement as the measure of ‘good’ and ‘bad’. Given that the Pareto optimal ideal of collective action may not be achievable due to the actual situation of decision costs and voter rationality being insufficient, an alternative to the ‘unanimity standard’ could be being consistent with the real content that may arise from a social contract in which everyone participates. This testing method also applies to legal institutions that have developed under spontaneous order, as well as elements that have been explicitly set aside in the past to achieve a specific goal (Müller, 2002). Therefore, the constitutional contract emphasizes that the evaluation criteria for rules are formed through consensus among participants, and the unanimous agreement principle is the only criterion for judging rules (Buchanan, 2002, p. 59).

Concluding thoughts

Although Buchanan’s constitutional contract was presented in a hypothetical form (Müller, 2002), it improved the contractual theory model by introducing elements such as the ‘individual,’ the ‘veil of uncertainty,’ ‘public choice’, ‘decision costs’ and the ‘unanimous consent principle’. The effects of the transformation of the relevant theory include the assertion of a constitutional contract that individuals are the creators of value and behavioral decision-makers (Vanberg, 2020) and proof that the state can achieve self-construction through nonviolent means, providing a solid theoretical foundation for democratic systems. Normative political theory does not need to borrow any external moral structure or ethical truth, human behavior only needs to meet reasonable assumptions, and rule systems can be expected to bring acceptable universal results to society. Broad contractarian theory compares politics to economic relations and supplements traditional theories of the production and exchange of goods and services with political market theory.Footnote 2 Human behavior in the market system and government behavior in political systems are now included in the same analytical trajectory, thereby changing the paradigm of viewing politics as an exogenous factor in economic policy-making models and of understanding the political process through heterogeneous thinking. The contractual mode suggests that policies, rules, and institutions are the result of subjective choices made by people rather than those entirely universal, abstract, and context-independent ideals of justice demanding what people should do; furthermore, whether justice is achieved depends on what rules individuals happen to agree upon. In short, these judgments attribute the construction of public order to the result of social interactions, without the need for explanations from perspectives such as ‘God’s will’, ‘social welfare’, and ‘collective preferences’. Compared with Rawls’ political liberalism, Buchanan’s constitutional contract provides participants with more information about social, political, and economic systems and informs them that their main reason for making constitutional choices is the uncertainty of future prospects. The interaction experience among individuals during the constitutional phase is of great significance for political liberalism, which advocates justice diversification because it appeals to the formation of rules in a normal situation through public choice. At the same time, the application of the continuous cost model can help determine the normal consequences of constitutional choices, while the concept of external costs not only explains the reasons why society needs to bear decision-making costs but also provides a method for evaluating collective decision-making. Buchanan’s reform of the traditional contractarian approach not only helps present the true face of the collective decision-making process (Vallier, 2018) but also helps establish an empirical theory about the actual logic of different individuals’ actions in the political system.

However, Buchanan’s constitutional contract has received criticism from various perspectives. Buchanan argued that individuals can autonomously choose moral norms and criteria for behavior evaluation, while a more critical view holds that the constitutional choice perspective overly emphasizes people’s initiative while ignoring the role of existing social structures in shaping individuals. In addition, critics also point out that the ‘economic man model’ is inappropriate in certain areas of human life, such as interactions within family and church environments. To effectively predict the future costs of collective choice systems, while considering that the majority of people are a mixture of moral beings, economic beings, and other factors, with different proportions of these elements, critics advocate for using a more balanced model as the human prediction model (Kogelmann, 2015). Buchanan criticizes Rawls for deriving a specific outcome from the ‘veil of ignorance,’ arguing that people’s judgments about fairness are matters of personal experience and that other outcomes can emerge beyond the ‘difference principle’. In contrast, the constitutional contract exhibits clear non-teleological characteristics. Buchanan recognizes unanimity as the only necessary element for establishing the legitimacy of rules. However, critics argue that the content of unanimity itself can be negated by another kind of unanimity, and in situations where each individual has veto power, no decision can be made. Additionally, Amartya Sen opposes Buchanan’s exclusive identification of justice through procedural mechanisms, as he believes that the constitutional contract only emphasizes procedural justice unilaterally while lacking consideration for the outcome (Dold, 2018). Given that multiple game equilibria arise in constitutional choices, a proceduralist approach cannot ensure that the normative stance of the constitutional outcome is consistent with prioritizing individual freedom. This highlights that universalism pursued in constitutional choices may not effectively promote freedom or prevent harm unless appropriate limitations are placed on predefined categories. However, Buchanan does not believe that universalism should not be restricted but emphasizes that the normative premise of limiting universalism should be unanimously agreed-upon at the constitutional level. In addition, the feasibility of the ‘principle of unanimous agreement’ has also been questioned. Amartya Sen believes that even in an ideal decision-making environment, it is difficult to eliminate conflicts between basic principles. Other critics point out that even if people can reach a consensus on constitutional commitments during the constitutional stage, differences in individual freedom or opportunities in the post-constitutional stage, such as unequal power relations, asymmetric information, a lack of effective guarantees, and unreasonable enforcement, can seriously damage valuable constitutional commitments. As previously mentioned, Buchanan believes that the unanimity principle is more likely to apply at the constitutional level than at the operational level of decision-making, but transferring it to the constitutional level would narrow the scope of the unanimity principle (Horn and Wagner, 2020). Furthermore, the abstractness and fuzziness of principles, as well as the rupture between rule selection and rule internal selection, would further expose the limitations of constitutional proceduralism in promoting good rules and raise doubts about the consistency of Buchanan’s constitutional contract theory.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this research, as no data were generated or analyzed.

Notes

In Social Choice, Democracy, and Free Markets (1999a [1954]), Buchanan criticizes Arrow for attributing rationality to the social group rather than its individual components. In his view, even if a collective faces a set of alternative options, the actual choice is made only by the individuals who participate in the decision-making process.

These theories include the use of concentrated interests and dispersed costs, the logic of special interest groups, electoral motives, term limits, policy myopia, and the perspective of policy economics.

References

Bertolini D (2019) Constitutionalizing Leviathan: a critique of Buchanan’s conception of lawmaking. Homo Oecon 36(1):41–69

Besley T (2007) The new political economy. Econ J 117(524):570–587

Brennan G, Buchanan JM (2004a) The power to tax, translated by Feng Keli and others. China Social Sciences Press, Beijing

Brennan G, Munger M (2014) The soul of James Buchanan? Indep Rev 18(3):331–342

Brennan J, Buchanan JM (2004b) Constitutional economics, translated by Feng Keli and others. China Social Sciences Press, Beijing

Buchanan JM (1975a) A contractarian paradigm for applying economic theory. Am Econ Rev 65(2):225–230

Buchanan JM (1975b) The limits of liberty: between anarchy and Leviathan. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Buchanan JM (2002) Property and freedom, translated by Han Xu. China Social Sciences Press, Beijing

Buchanan JM, Tullock G (2000) The calculus of consent: logical foundations of constitutional democracy, translated by Chen Guangjin. China Social Sciences Press, Beijing

Buchanan JM, Vanberg VJ (2002) Constitutional implications of radical subjectivism. Rev Austrian Econ 15(2):121–129

Cardinale I, Scazzieri R (2018) The Palgrave handbook of political economy. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Congleton RD (2014) The contractarian constitutional political economy of James Buchanan. Const Political Econ 25(1):39–67

Dias MA (2009) James Buchanan e a “política” na escolha pública. Ponto-e-Vírgula 6:203

Dold MF (2018) How to criticize James M. Buchanan? Amartya K. Sen on the normative premises of constitutional contractarianism. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324056521. Accessed 18 Dec 2019

Hobbes (1985) Leviathan, translated by Li Sifu and others. Commercial Press, Beijing

Holcombe RG (2020) James M. Buchanan’s constitutional project: past and future. Public Choice 183(3):371–387

Horn K, Wagner RE (2020) James M. Buchanan—a theorist of political economy and social philosophy. Const Political Econ 31(2):259–265

Kliemt H (1994) The calculus of consent after thirty years. Public Choice 79(3):341–353

Kogelmann B (2015) Modeling the individual for constitutional choice. Const Political Econ 26(4):455–474

Lewis P, Dold M (2020) James Buchanan on the nature of choice: ontology, artifactual man and the constitutional moment in political economy. Camb J Econ 44(5):1159–1179

McLellan J (2003) A history of western political thought, translated by Peng Huaidong. Hainan Publishing House, Haikou

Meadowcroft J (2016) Commons, anticommons and public choice: James Buchanan on liberal democracy. Econ Aff 36(2):224–228

Melenovsky CM (2019) The status quo in Buchanan’s constitutional contractarianism. Homo Oecon 36(1):87–109

Müller C (2002) The methodology of contractarianism in economics. Public Choice 113(3):465–483

Rawls J (1988) A theory of justice, translated by He Huaihong and others. China Social Sciences Press, Beijing

Rizzo MJ, Dold MF (2020) Can a contractarian be a paternalist? The logic of James M. Buchanan’s system. Public Choice 183(3):495–507

Vallier K (2018) Social contracts for real moral agents: a synthesis of public reason and public choice approaches to constitutional design. Const Political Econ 29(2):115–136

Vanberg VJ (2004) The status quo in contractarian-constitutionalist perspective. Const Political Econ 15(2):153–170

Vanberg VJ (2005) Market and state: the perspective of constitutional political economy. J Institutional Econ 1(1):23–49

Vanberg VJ (2014) James M. Buchanan’s contractarianism and modern liberalism. Const Political Econ 25(1):18–38

Vanberg VJ (2020) J. M. Buchanan’s contractarian constitutionalism: political economy for democratic society. Public Choice 183(3):339–370

Voigt S (1997) Positive constitutional economics: a survey. Public Choice 90(1):11–53

Wagner RE (1987) James M. Buchanan: constitutional political economists. Regulation 11:14

Wagner RE (2019) James M. Buchanan: a theorist of political economy and social philosophy. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, Basingstoke

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, LMY; methodology, LMY; validation, LMY; formal analysis, LMY; investigation, LMY; resources, LMY; data curation, LMY; writing—original draft preparation, LMY; writing—review and editing, LMY; supervision, LMY; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All analyses were based on previously published studies; thus, no ethical approval was required.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, M. Structural and functional analysis of Buchanan’s constitutional contract. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 111 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02628-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02628-y

- Springer Nature Limited