Abstract

The 2007–2009 Great Recession has led to an unprecedented increase in public debt in many countries, triggering substantial fiscal adjustments. What are the distributional consequences of fiscal austerity measures? This is an important policy question. This paper analyzes the effects of fiscal adjustments for a panel of 17 OECD countries over the last 30 years, complemented by a case study of selected fiscal adjustment episodes. The paper shows that fiscal adjustments are likely to raise inequality through various channels including their effects on unemployment. Spending-based adjustments tend to worsen inequality more significantly, relative to tax-based adjustments. The composition of austerity measures also matters: progressive taxation and targeted social benefits and subsidies introduced in the context of a broader decline in spending can help offset some of the adverse distributional impact of fiscal adjustments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Great Recession of 2007–2009 has led to an unprecedented increase in public debt, raising serious concerns about fiscal sustainability. Against this backdrop, many governments have been making substantial fiscal adjustments through a combination of spending cuts and tax hikes to reduce their ratios of debt to GDP. What are the distributional consequences of fiscal austerity measures?Footnote 1 This is an important policy question. Preventing a significant increase of income inequality during the adjustment period is critical to the sustainability of deficit reduction efforts, as a fiscal contraction that is perceived as being fundamentally unfair will be difficult to maintain. Moreover, high income inequality can harm long-term growth through various channels (for example, see Easterly, 2007; Berg et al., 2011; Woo, 2011).Footnote 2 Surprisingly, however, there has been little systematic analysis of the distributional effects of fiscal adjustments.Footnote 3

This paper provides evidence on the effects of fiscal adjustment episodes and a set of fiscal variables (tax structure, specific taxes, and expenditures) on income inequality in a panel of advanced economies over the last three decades, which is complemented with a case study of selected fiscal adjustments episodes. For the econometric analysis, the paper builds on a large literature on the determinants of cross-country variations in income inequality (for example, see De Gregorio and Lee, 2002; IMF, 2007; Barro, 2008).

Specifically, we address the following set of questions: Does fiscal austerity worsen income inequality? If so, how and by how much? Does the size of fiscal adjustment matter? Our results suggest that fiscal contractions tend to increase income inequality, including through their effects on unemployment. Alternative estimation methods find a similar range of impact magnitude: on average, a fiscal adjustment of 1 percentage point of GDP is associated with an increase in the disposable income Gini coefficient of around 0.4–0.7 percent over the first 2 years. Given the inelasticity of the Gini coefficient, this relatively small coefficient unveils a rather sizeable impact of fiscal contraction on income distribution. Spending-based adjustments tend to significantly worsen inequality, relative to tax-based adjustments. So do large-sized adjustments (those greater than 1½ percent of GDP). This seems to reflect the fact that large-sized fiscal adjustments tend to be longer in duration and mostly expenditure based, which is confirmed in the case study. Unemployment also tends to increase inequality, and hence, to the extent that fiscal adjustment raises unemployment, it constitutes an important channel through which adjustment affects inequality. About 15–20 percent of the increase in inequality due to fiscal adjustment may be occurring via the increase in unemployment.

The composition of fiscal adjustment also matters: progressive taxation and targeted social benefits and subsidies introduced in the context of a broader reduction in spending can help offset some of the adverse distributional impact of fiscal adjustment. For example, discretionary spending cuts could be combined with an enhancement of social safety nets, supported by means testing and efficient monitoring. Indeed, the progressivity of taxation (as measured by the ratio of direct to indirect taxes), social benefits (including health care, social security pensions, and unemployment compensation), and subsidies tend to be consistently associated with lower inequality for disposable income in the regressions, even after controlling for other determinants of inequality.Footnote 4 These results support the view that in advanced economies, reforms since the 1980s have been a factor behind rising income inequality by lessening the generosity of social benefits and the progressivity of income tax systems. In addition, fiscal policy can favorably influence long-term trends in both inequality and growth by promoting education and training among low- and middle-income workers.

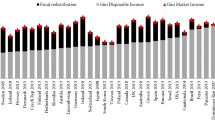

These findings have important policy implications for the economies that are currently undertaking fiscal adjustments. Adjustment packages should be carefully designed to limit negative social effects. It may be still too early to fully assess the distributional effects of the crisis and fiscal adjustment in these economies, as the distributional effects may take many years to work through the system.Footnote 5 Nonetheless, some patterns already seem to emerge in the same direction as our findings point to. In three countries (Ireland, Lithuania, and Spain), large increases in inequality seem to be associated with sharper increases in unemployment (Figure 1). For countries that provided less discretionary fiscal support during the crisis, inequality has not increased as much. In Ireland, inequality initially declined during the crisis because of a relatively large fall in top incomes (especially, capital incomes), tax increases, and an expansion of redistributive social transfers. However, the latest data suggest that income inequality started to widen as the crisis deepened and fiscal adjustment intensified.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: "Data, Trends in Income Distribution, and Related Studies" section describes inequality data and trends of income distribution, and briefly reviews related studies. "Econometric Analysis: Fiscal Adjustment and Inequality" section presents the main econometric analysis. "Case Study of Fiscal Adjustment Episodes" section discusses a case study of selected episodes. Concluding remarks are in "Concluding Remarks" section.

Data, Trends in Income Distribution, and Related Studies

Data on Income Distribution

There have been substantial efforts to compile cross-country datasets on income inequality over the last decades. Two datasets have been particularly influential: the Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) and the dataset assembled by Deininger and Squire (1996) for the World Bank and its successor, the World Income Inequality Database (WIID) of the United Nations University (UNU-WIDER, 2008). However, both have limitations for international comparison purposes. The LIS has produced the most comparable income inequality statistics currently available, but it covers relatively few countries and years—on average, inequality in each of these countries is observed in just 5 years, with most of the observations dating from after 1993. The Deininger and Squire dataset and the WIID, on the other hand, provide many more observations, but they are often not comparable across countries or even over time within a single country because they are based on different income definitions (e.g., market income, disposable income, or consumption expenditure) and different reference units (e.g., households, household adult equivalents, or persons) (See Atkinson and Brandolini, 2001; Smeeding, 2005; Babones and Alvarez-Rivadulla, 2007 among others).

This paper uses income inequality indicators from the Standardized World Income Inequality Database (SWIID) because of its better coverage and quality. The SWIID, which is obtained from Solt (2009; 2012 update), maximizes the comparability of income inequality data while preserving the broadest possible coverage across countries and over time. It standardizes the WIID database and provides comparable Gini coefficients for market and disposable income for up to 153 countries for as many years as possible from 1960 to 2011 (see Solt, 2009) for details).

As further robustness checks, we use alternative data on Gini coefficients for disposable income and alternative measures of income inequality (e.g., ratios of top to bottom quintiles/deciles, and labor income share) compiled from original sources including the WIID, the LIS, World Bank’s PovcalNet, and Eurostat. Measures of income inequality are relatively highly correlated with each other (Table 1)—for example, the correlation coefficient between Gini indices for disposable income from the SWIID and those in alternative dataset compiled from the aforementioned original sources is 0.95 (p value = 0.00).

Trends in Income Inequality

Data suggest that income inequality has increased since the 1980s in most advanced and many developing economies. This reflects an array of factors including skill-biased technological progress, technology diffusion, international trade, and market reforms. Inequality in disposable income (income after taxes and transfers) exhibits a similar upward trend, but there is a wider variation across countries and regions, largely due to different degrees of progressivity in income tax systems and spending policies (Figure 2).Footnote 6

During 1980–2010, the average disposable income Gini coefficients in advanced economies and emerging Europe, the most equal regions, increased by 3 and 6 percentage points, respectively. The Gini coefficients also increased in most countries in Asia and the Pacific region during the same period. In the two most unequal regions (Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America), however, income inequality increased in the 1980s and 1990s but subsequently declined markedly.

In advanced economies, redistributive fiscal policy has played a role in reducing inequality in market income, particularly via social transfers. However, reforms since the mid-1990s have lessened the generosity of social benefits, particularly unemployment and social assistance benefits, contributing to rising income inequality (OECD, 2011 and Figure 3). Consistent with this observation, the correlation coefficient between the Gini coefficient for market income and that for disposable income has markedly declined from 0.5 in the 1990s to 0.37 in the 2000s.

In emerging and low-income economies, the redistributive capacity of fiscal policy has historically been limited because of weak taxation systems (large parts of the economy are outside the income tax system and the efficiency of tax collection is relatively low) and poorly targeted social transfers (see Chu et al., 2004; Gemmell and Morrissey, 2005; and Box 1). Social benefits and subsidies increased in these countries since the 1980s. However, their declining ratio of direct to indirect taxes indicates decreasing tax progressivity. Overall, data point to a strong negative association between social spending and disposable income inequality but to a less clear cut relationship between the ratio of direct to indirect taxes and inequality.Footnote 7

Related Studies

The large empirical literature on the determinants of income inequality finds that national income per capita, education, trade openness, and technological change are the main determinants of cross-country variations in income inequality (e.g., De Gregorio and Lee, 2002; Acemoglu, 2003; IMF, 2007; Meschi and Vivarelli, 2007; ADB, 2007; Barro, 2008; IMF, 2010a among others). Evidence shows a Kuznets inverted-U relationship between income level and income inequality and suggests that a higher level of educational attainment reduces income inequality, whereas education inequality increases income inequality. Depending on the level of economic development, trade openness may raise inequality, although it may actually improve income distribution indirectly as trade stimulates growth. Building on this literature, our analysis focuses on the effects of fiscal adjustment and a set of fiscal variables on inequality in disposable income, while controlling for the standard explanatory variables of inequality.

On the implications of fiscal policies for income inequality, studies find that countries’ differences and historical trends in income inequality can be partly explained by the level and progressivity of tax and spending policies (Bastagli et al., 2012; Chu et al., 2004). Yet, specific fiscal policy measures can have either equalizing or disequalizing effects on income distribution. In general, direct taxes (e.g., personal income tax and to a lesser extent of corporate income tax) and social expenditure are found to improve income distribution, while indirect taxes (including consumption taxes and custom duties) tend to increase inequality (Muinelo-Gallo and Roca-Sagales, 2011, 2013). Clearly, the impact would ultimately depend on the incidence of the tax and precisely on which socio-economic group the tax change is passed to (Clements et al., 2015). It has been found that changes in higher VAT rates can be fully shifted to consumers, while the benefits of reduced rates are not (Benedek et al., 2015). Similarly, earned income tax credits in the United States are found to benefit more employers than workers (Rothstein, 2010).

Overall, spending, particularly in the form of family and housing benefits, seems to have a higher redistributive impact than taxes (Martinez-Vazquez et al., 2012; Joumard et al., 2012; Paulus et al., 2009; Chu et al., 2004); although in the case of developing countries, spending on education and health seems to have a strong equalizing effect (Lustig 2015). The impact of fiscal policies on the income distribution of developing countries tends to be similar to that of advanced economies (Cubero and Hollar, 2010; Gemmell and Morrissey, 2005); yet the higher level of disposable income inequality in low-income economies is in part explained by lower levels of taxes and transfers (Bastagli et al., 2012). A crucial aspect to be considered both for taxes and spending is the extent at which the measure can effectively be well targeted. In the case of reduced VAT rates for food or other items widely consumed by the poor, Keen (2014) demonstrates how these measures tend to be badly targeted and end up usually benefitting the better off.

By contrast, only a few studies have looked at the distributional effects of fiscal adjustments. Mulas-Granados (2005) finds evidence that inequality tends to rise following fiscal adjustments in a panel of 15 EU nations during 1960–2000 and that spending cuts are detrimental to income distribution. More recently, Agnello and Sousa (2014) study fiscal adjustment episodes in 18 OECD countries from 1978 to 2009 and present evidence that income inequality rises during the periods of expenditure-based adjustments. Also, they find that inequality increases when fiscal adjustment follows periods of financial turmoil and when the country is experiencing low growth and/or high inflation. Ball et al. (2011) examine the impact on short- and long-term effects on unemployment of fiscal adjustments and find evidence that unemployment tends to rise following adjustments in advanced economies.Footnote 8 Through a case study analysis, Rawdanowicz et al. (2013) show that for 5 out of 10 OECD countries, the Gini coefficient increased at times of fiscal contraction, a result interpreted as mostly due to increasing dispersion of market income and less redistribution of taxes and transfers. About three countries reported an unchanged Gini coefficient, and only in two countries (Ireland and Denmark) the Gini coefficient declined. A similar study conducted by Avram et al. (2013) assesses the impact of nine adjustment packages between 2008 and 2012 in selected European countries. The study finds that in 5 countries, the adjustment measures were progressive as they hit households in the richest quintiles. In two economies, however, (Estonia and Lithuania) the measures hit mostly the poorest deciles. Through econometric estimates on 17 advanced economies over the period 1978–2009, Furceri et al. (2015) find that fiscal adjustment tends to lead to an increase in inequality in the short and medium term, but no conclusive evidence is found regarding whether tax-based or expenditure-based adjustments have different effects.

Econometric Analysis: Fiscal Adjustment and Inequality

This section presents evidence on the relationship between inequality in disposable income and fiscal variables (including fiscal adjustment). Based on an annual panel dataset for a group of advanced and emerging market economies over the last three decades,Footnote 9 we examine the following two sets of specific questions:

What are the distributional consequences of fiscal adjustment or contraction? Does fiscal austerity worsen the income inequality? If so, how and how much? Does the size of fiscal adjustment matter?

Estimated Model

The analysis builds on a large empirical literature on the determinants of income inequality, which finds that national income per capita, education, trade openness, and technological change are the main determinants of cross-country variations in income inequality (e.g., De Gregorio and Lee, 2002; IMF, 2007; Barro, 2008). While controlling for standard explanatory variables, we assess the effects of fiscal adjustment and a set of fiscal variables (tax structure, specific taxes, and expenditures) on inequality in disposable income.

The baseline panel regression specification is as follows:

where G it denotes the log of disposable income-based Gini coefficient, a measure of the income distribution for country i and year t; ν i denote the country-specific fixed effects (to control for country-specific factors including the time-invariant component of the institutional environment); η t are the time-fixed effect (to control for global factors); ε it is an error term; X it−1 is a vector of economic control variables; and Z it is the measure of fiscal adjustment or fiscal variables.

Two econometric methods are employed to estimate the panel regression. The first approach uses the fixed-effects (FE) panel regression, with Driscoll and Kraay (1998) standard errors that are robust to very general forms of cross-sectional and temporal dependence. The error structure is assumed to be heteroskedastic, autocorrelated up to two lags (to account for the persistence of income inequality), and correlated between the panels (i.e., countries) possibly due to common shocks, say, to technology or international trade. The second approach adopts a seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) for panel data which consists of two regression equations—one for disposable income Gini coefficient and the other for market income Gini coefficient. If the errors are correlated across the equations (i.e., the unobserved determinants of inequality in market income and disposable income could be correlated), the SUR estimator will be more efficient.Footnote 10 In addition, we use alternative regression specification and estimation methods as robustness checks, including a dynamic panel regression (see "How Do Different Fiscal Adjustment Measures Affect Income Inequality?" section below), as well as ordinary least squares (OLS) and panel-corrected standard error (PCSE) estimates, which also allow the variance–covariance matrix of the estimates to be consistent when the error terms are heteroskedastic and/or contemporaneously correlated across panels or autocorrelated within panel (Beck and Katz, 1995). The results are broadly similar.Footnote 11

X it-1 (the vector of economic control variables) includes the following:

-

Income per capita as measured by (i) the log of income per capita and (ii) the square of log of income per capita to consider the Kuznets relationship (Barro, 2008; De Gregorio and Lee, 2002).Footnote 12

-

Educational attainment as measured by the average number of years of secondary schooling of the population aged 15 and over. The literature emphasizes education as one of the major factors affecting the degree of income inequality. Many studies have found a negative association between inequality and education (see De Gregorio and Lee, 2002 and references therein).

However, the theoretical relationship remains ambiguous because of two possible conflicting effects from an expansion of education on earnings distribution (Knight and Sabot, 1983): (i) the “composition” effect, which increases the relative size of the group with more education and tends initially to raise income inequality but eventually to lower it; (ii) the “wage compression” effect, which decreases the premium on education as the relative supply of educated workers increases, thereby decreasing income inequality. Thus, the net effect of increased education on the distribution of income is ambiguous. However, in advanced economies with relatively high level of education in the population, both effects are likely to produce a negative relationship between education and inequality.

-

Trade openness (sum of exports and imports as percent of GDP) to control for the impact on inequality of trade globalization. The standard theory of international trade suggests that trade openness would affect income distribution differently according to countries’ relative factor endowments: developed countries should experience a rise in the relative return to capital and greater income inequality, since they are relatively abundant in capital (and scarce in labor). The opposite should happen in emerging market and developing countries, since they are relatively abundant in labor. However, the effects of trade openness on income distribution have been found to be quite varied, making it difficult to predict their direction.Footnote 13 While IMF (2007) finds evidence that trade openness is associated with a reduction in inequality, others find the opposite.Footnote 14 Yet, the evidence is not conclusive (see Krugman, 2008; Meschi and Vivarelli, 2007; ADB, 2007 for more discussions).

-

Unemployment rate not surprisingly, a greater portion of unemployed (and inactive) workers are found to be in the bottom income quintile in the OECD countries (Martinez et al., 2001). Thus, higher unemployment may be associated with greater inequality.

-

The share of information technology (IT) capital in the total capital stock as a proxy for skill-biased technological progress (data from Jorgenson and Vu, 2007, with a 2011 update). Skill-biased technological progress is found to have made the biggest contribution to rising income inequality over the recent decades (Autor et al., 1998; Acemoglu, 2003; IMF, 2007).

-

Inflation tends to hurt the poor more than other income groups and to worsen inequality (Easterly and Fisher, 2001; Bulir, 1998). This may be in part due to differences in wealth composition and transaction patterns (the fraction of household wealth held in liquid assets, such as currency, decreases with income and wealth) and differential protection of earnings streams against inflation (wage earners at the bottom of the income scale are generally much less protected from cyclical real wage fluctuations, such as the minimum wage).

-

Incidence of banking crises banking crises can affect inequality because the poor have few resources to protect themselves against adverse shocks and very limited access to credit and insurance. Also, lack of education and skills makes the poor less mobile across regions and economic sectors, reducing their ability to switch jobs and relocate in response to shifting demand conditions. However, the evidence is mixed. For example, in the aftermath of the 1997 Asian crisis, Korea and (to a much lesser degree) the Philippines experienced an increase in income inequality, whereas Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia did not. In a recent study, Atkinson and Morelli (2011) do not find any systematic relationship between macroeconomic disasters and the inequality outcome (see also Glaeser, 2010). We tried the indicator of banking crises, but the results were not significant and did not alter the main conclusions.

Z it − 1 contains measures of fiscal consolidation or contraction and fiscal variables as follows:

-

Fiscal consolidation (spending and tax measures, in percent of GDP) from the action-based fiscal consolidation data for 17 member countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) for the period of 1978–2009 (from Devries et al., 2011).Footnote 15

-

Ratio of direct to indirect taxes, a measure of the tax structure (from the database of the Fiscal Affairs Department of the IMF), with a higher value indicating a potentially greater progressivity of the tax system in a country.

Identifying Fiscal Adjustment Episodes

To assess the impact of fiscal adjustment on inequality, this study uses the consolidation episodes identified by Devries et al. (2011) for a set of 17 OECD countries during the period 1978–2009 (See Table 3 for a list of selected episodes). Following Ramey and Shapiro (1998), Ramey (2011), and Romer and Romer (2010), fiscal adjustment episodes are captured by examining policymakers’ intentions and actions from policy documents such as budget documents, budget speeches, central bank reports, Convergence and Stability Programs submitted by the authorities to the European Commission. In particular, the analysis makes sure that each fiscal adjustment included in the dataset was primarily driven by intentions to reduce deficit rather than responses to prospective economic conditions and that the announced measures were implemented. The dataset includes 173 years of fiscal adjustments across 17 countries and documents detailed information for each country. It provides discretionary changes in the fiscal balance, distinguishing between discretionary changes in tax revenue and discretionary changes in expenditure. It also indicates whether measures where permanent or temporary, allowing to capture whether the expansion or contraction was reverted in the following year. The dataset includes fiscal consolidations that are followed by an adverse shock and an offsetting countercyclical discretionary stimulus. The budgetary effect of the fiscal consolidation measures are captured in the year in which they come into effect.

This new approach for the identification of fiscal adjustment episodes may solve for the bias that emerges using more conventional approaches, which identify fiscal adjustment with positive changes in the cyclically adjusted primary balance (CAPB), including specific changes in the cyclically adjusted revenue or expenditure.Footnote 16 For example, in the approach proposed by Giavazzi and Pagano’s (1996), a fiscal consolidation consists of a positive change in the CAPB of at least 2 percent of GDP in 1 year and at least 1.5 percent on average in the last 2 years. Alternatively, in the methodology proposed by Alesina and Ardagna (1998) a consolidation episode takes place when the CAPB shrinks by 3 percentage points of GDP for a single year or when cumulative changes in the CAPB are at least 5, 4, and 3 percentage points of GDP in, respectively, 4, 3, or 2 years.

As discussed in Devries et al. (2011), these approaches present some shortcomings that might limit statistical inference. First, changes in the cyclically adjusted balances may include macroeconomic changes other than policy driven ones. Second, they might reflect policy changes induced by current economic conditions, if for instance the government is reducing spending to reduce aggregate demand; hence, the measure would be affected by reverse causality. The narrative approach would on the contrary guarantee that the policy responses are systematically correlated with economic activities. Comparing the conventional approach (using Alesina and Ardagna, 2010) and the narrative approach by Devries et al. (2011), demonstrates that in 12 cases the CAPB metric inaccurately identifies the size of the adjustment. In the case of Italy in 1993 for instance, the large economic contraction could have caused the CAPB to be highly inaccurate. As a result of this bias, the conventional approaches tend to overstate the expansionary effects of fiscal adjustments and would be more in favor of the expansionary fiscal contraction hypothesis. Similarly, Figure 4 shows an imperfect matching of changes in the CAPB and changes in the deficit as identified by the Devries et al. (2011) dataset, which suggests that specific budgetary measures to reduce the deficits are not always reflected in changes in the CAPB. For these reasons, this study uses the Devries et al. (2011) dataset in the regression analysis and complements this dataset with three CAPB datasets for the analysis of case studies.

How Do Different Fiscal Adjustment Measures Affect Income Inequality?

In this section, we focus on the impact on inequality of fiscal adjustment or contraction for 17 OECD countries for 1978–2009 using a parsimonious specification of Eq. (1).Footnote 17 The regression results from both the SUR and FE approaches suggest that income inequality tends to rise during periods of fiscal adjustment, especially when the adjustment is based on a retrenchment in spending.Footnote 18 A fiscal adjustment amounting to 1 percentage point of GDP is associated with an increase of about 0.6–0.7 percent in inequality of disposable income (as measured by the Gini coefficient) in the following year (Table 2, columns 1, 4, 7, and 10). Given the inelasticity of the Gini, this relatively small coefficient unveils a sizeable impact of fiscal consolidation, particularly if compounded over multiple years.Footnote 19 An alternative dynamic panel regression specification confirms that income inequality increases following fiscal adjustment, with the cumulative effect peaking after 5–6 years and fading by the tenth year (see "How Do Different Fiscal Adjustment Measures Affect Income Inequality?" section below). The order of the impact magnitude also turns out to be in a similar range—a fiscal adjustment of 1 percentage point of GDP is associated with an increase in the disposable income Gini coefficient by around 0.4 percent in the following year. The effect of large fiscal adjustments (greater than about 1.5 percent of GDP) is somewhat larger and statistically more significant, compared to small adjustments (Table 2, columns 2, 5, 8, and 11).Footnote 20

Comparing spending-based adjustments with tax-based ones, the coefficients of measures of spending-based adjustments are statistically significant and of positive sign (+), indicating that spending cuts are associated with an increase in inequality. The estimated coefficients suggest that a spending cut of 1 percentage point of GDP is associated with an increase of about 1.5–2 percent in the Gini coefficient (columns 3, 6, 9, and 12). In contrast, the coefficients of tax-based adjustments are not significant but of negative sign (−). The contrasting results between spending- and tax-based adjustments are intuitive—for example, income tax measures can actually lower the inequality, depending on the progressivity of the particular measure, while the indirect effects through an increase in unemployment due to their recessionary effects may increase inequality. Taken together, therefore, the net effects of tax-based adjustments can be somewhat ambiguous.

On the other hand, the progressivity of taxation, as measured by the ratio of direct to indirect taxes, is negatively associated with disposable income inequality (Figure 3). Columns (7)–(9) suggest that an increase of 1 in that ratio is associated with a reduction of about 2.5 percent in inequality.Footnote 21 To put this in perspective, let us consider an illustrative example. In 2009, the disposable income-based Gini coefficients in Denmark and Portugal were 26.5 and 34, while the ratios of direct to indirect taxes were 1.91 and 0.74, respectively. The difference in the direct to indirect tax ratio between the two countries explains about 12 percent of the difference in inequality between them.

Consistent with the literature, education and trade openness are significantly associated with lower inequality. According to the estimated coefficients, a 1 percent increase in the average years of schooling is associated with about 0.04–0.12 percent reduction in inequality. On the other hand, a 1 percentage point of GDP increase in trade openness is associated with about 0.1 percent reduction in inequality. Evidence of an inverse U-shaped relationship between income per capita and inequality is also found, with the inequality starting to decrease when real income per capita exceeds about $17,700 in 2005 international dollars (based on column 1).Footnote 22 Also, it is interesting to note that the coefficients of unemployment are of positive sign but insignificant, after controlling for measures of fiscal adjustments (columns 4–12)—for example, if we drop the fiscal adjustment variable from the regression in column (4), then the coefficient of unemployment becomes significant at 1 percent (the coefficient estimate is 0.003 and its implied magnitude of impact on inequality turns out to be similar to those reported in "Dynamic Effects of Fiscal Adjustment on Income Inequality" section below).

Dynamic Effects of Fiscal Adjustment on Income Inequality

Since fiscal adjustments may have lingering effects on inequality over time, we further investigate the dynamic impact of fiscal adjustment on inequality by adopting a dynamic panel regression specification, again for the 17 OECD countries over 1978–2009. To this end, a univariate autoregressive model is extended to include the current and lagged impacts of the fiscal shock and to derive the relative impulse response functions (IRFs) in an unbalanced annual panelFootnote 23:

where i is a country; t is a year; g it denotes the Gini coefficient for disposable income; v i are country-specific fixed effects; η t are time-fixed effects (to control for global factors); and F it is a measure of fiscal consolidation or contraction (as percent of GDP) from Devries et al. (2011). The number of lags has been restricted to two; the presence of additional lags was rejected by the data.Footnote 24 Impulse response functions (IRFs) are obtained by simulating a shock on the fiscal consolidation. The shape of these response functions depends on the value of the δ and β coefficients. For instance, the simultaneous response will be δ 0, while the 1-year ahead response will be δ 1 + β 0 δ 0, and so on.

Overall, the Gini coefficient for disposable income tends to start rising about 1 year after the consolidation. A fiscal adjustment or contraction of 1 percentage point of GDP raises the Gini coefficient by 0.13 points in the second year and by 0.4 cumulatively over 5 years (Figure 5).Footnote 25 On average, the 0.13 and 0.4 increases in the Gini are equivalent to increases in inequality of 0.4 percent and 1.3 percent, respectively (the OECD average of the Gini coefficient for disposable income in the sample period is 30.02). The order of magnitude of the impact (a 0.4 percent rise in the first 2 years) is comparable to the 0.6–0.7 percent increase suggested by the baseline regression (Table 2). Also, an alternative measure of fiscal consolidation from Alesina and Ardagna (2010) is used.Footnote 26 The result is qualitatively similar, suggesting that a consolidation raises the Gini coefficient by 0.12 points in the second year and by 0.66 cumulatively over 5 years.

To gauge the impact of fiscal adjustment on inequality through the channel of unemployment, the same model described above is used to derive the dynamic impact of fiscal adjustment on unemployment (Figure 5). Fiscal adjustment seems to start affecting unemployment immediately, with a fiscal contraction of 1 percent of GDP leading to a 0.19 percentage point increase in the unemployment rate in the first yearFootnote 27 and 1.5 percentage points cumulatively over 5 years. The impact subsequently gets smaller, disappearing by the tenth year and then turning negative. Coefficients of the measure of fiscal adjustment and its two lagged terms are jointly significant at the conventional level. However, if an alternative measure of fiscal adjustment from Alesina and Ardagna (2010) is used for the same exercise on unemployment, none of the coefficients of fiscal adjustment and its two lagged terms are individually or jointly significant. According to the lower estimates in Table 3 (columns 1–8), a 1 percentage point increase in unemployment rate is associated with an increase in inequality of about 0.3–0.4 percent, which implies that about 15–20 percent of the increase in inequality due to fiscal adjustment may be occurring via the increase in unemployment.

The results are broadly similar if we use either alternative datasets (from World Income Inequality Data (WIID), Luxembourg Income Study (LIS), and the World Bank’s PovcalNet) or alternative measures of inequality (including ratios of top to bottom quintiles/deciles; (see Appendix Table A2).

Case Study of Fiscal Adjustment Episodes

We examine fourteen selected large fiscal adjustment or consolidation episodes and highlight their salient features. To do this, we obtain adjustment episodes using three methodologies based on the cyclically adjusted primary balance. We use (i) the approach proposed by Giavazzi and Pagano’s (1996), where fiscal consolidation consists of a positive change in the CAPB of at least 2 percent of GDP in 1 year and at least 1.5 percent on average in the last 2 years; (ii) the methodology proposed by Alesina and Ardagna (1998), where a consolidation episode takes place when the CAPB shrinks by 3 percentage points of GDP for a single year or when cumulative changes in the CAPB are at least 5, 4, 3 percentage points of GDP in, respectively, 4, 3, or 2 years; and (iii) the methodology proposed by Afonso (2010) which identifies consolidations with positive change in the CAPB of at least one and a half times the standard deviation (from the reference country panel) in 1 year or when the change in the CAPB is at least one standard deviation on average in the last 2 years. Complementing the narrative approach with these three methodologies, we selected seven expenditure-based consolidation episodes and seven revenue-based consolidation episodes (Table 3).Footnote 28

We then examine for each episode the corresponding change in the Gini coefficient, from the first year of the episode to the year after consolidation. On average, we find that spending-based consolidations tend to be associated with increases in income inequality (Figure 6). Looking at the simple average, the Gini coefficient increased by about 0.3 after spending-based consolidations, while it declines by 0.1 in the case of tax-based episodes. This seems to be largely because lower income earners are typically more affected by spending cuts as a larger portion of their disposable income comes from public spending and they are more vulnerable to losing their jobs. In contrast, tax-based consolidations tend to have mixed net effects on inequality: direct taxes tend to be progressive, whereas indirect taxes are regressive. Looking at the episodes, spending-based consolidations tend to be larger in size and longer in duration, which could be another reason for the more pronounced effects on inequality, than tax-based consolidations.Footnote 29

Sources: Authors’ estimates; IMF-Fiscal Affairs Department Database; Eurostat; Standardized World Income Inequality Database (SWIID); and national sources.

Changes in Income Inequality: Spending-Based versus Tax-Based Consolidation Episodes

Note: Episodes drawn from World Economic Outlook action-based consolidation database, and size of fiscal consolidation calculated as the change in structural balances. Episodes absent from the database but with large structural changes (annual increase > 0.5 percent of GDP) are also included.

That said, the net effect of a fiscal consolidation on inequality depends crucially on the specific composition of austerity measures. Cuts in social benefits tend to worsen inequality more than other spending reductions, for example, public wage cuts. Fiscal consolidations in Spain, 1992–1998 consisted of across-the-board spending cuts, while protecting social benefits. Also, addressing tax evasion and tax loopholes was an alternative way to generate public savings without necessarily elevating the income inequality (e.g., Germany 1996–1999).

In terms of the timing of consolidation, consolidations undertaken during recessions could have a greater impact on inequality. In particular, social benefit cuts and tax increases amid rising unemployment (as, for example, in Spain, 1992–1998, and Sweden, 1996–1998) seem to have led to higher inequality than those undertaken during non-recession periods (such as those in Austria, 1996–1997, and Belgium, 1996–1997). This suggests the importance of unemployment benefits and more generally, social protection in assisting the most vulnerable. In a similar vein, to the extent that active labor market measures (such as job search assistance, training, and incentives to hire workers) help alleviate (long-term) unemployment, they may help mitigate the deterioration in income distribution.

The recent consolidation experience in Ireland shares many of these features, although it is difficult to disentangle the distributional impact of consolidation itself from that of the financial crisis and ensuing recession. Inequality initially fell as upper income groups suffered major income losses, while taxes increased and redistributive social transfers expanded. However, the impact of the deepening crisis and recession quickly spilled over to broader income groups via rising unemployment. Against this backdrop, the government had to embark on a large fiscal consolidation in 2010 due to adverse market reactions to the soaring sovereign debt. The consolidation package was sizable and mainly expenditure based. Public sector wage cuts mainly affected the middle upper class which might have mitigated the rising inequality, whereas social benefit cuts (family allowances, old-age benefits) heavily weighed on the lower income group, contributing to higher inequality (see 2010 Survey on Income and Living Conditions for Ireland). Despite some offsetting tax measures that were progressive in nature, the largely spending-based consolidation in 2010 amid deepening crisis and recession appears to start increasing income inequality.

Concluding Remarks

This paper examined the effects of fiscal consolidation or contraction and a set of fiscal variables (tax structure, specific taxes, and expenditures) on inequality in disposable income by using an econometric analysis for a panel of advanced and emerging economies for the last three decades as well as a case study of selected consolidation episodes. The results suggest that fiscal consolidations tend to increase income inequality. On average, a consolidation of 1 percentage point of GDP is associated with an increase in the disposable income Gini coefficient of around 0.4–0.7 percent over the first 2 years. Spending-based consolidations tend to significantly worsen inequality, relative to tax-based consolidations. So do large-sized consolidations. The paper also found that unemployment is an important channel through which consolidation increases inequality.

The composition of austerity measures also matters, and better-designed tax and social benefits policies can help mitigate the adverse effects on income inequality of fiscal adjustments. Indeed, progressive taxation and social benefits are consistently associated with lower inequality for disposable income. These results are consistent with the view that in advanced economies, reforms since the 1980s have been a factor behind rising income inequality by lessening the generosity of social benefits and the progressivity of income tax systems.

More generally, fiscal policy can favorably influence long-term trends in both inequality and growth by promoting education and training among low- and middle-income workers. Education and skill-biased technological progress are associated with lower and greater inequality, respectively. In addition, trade openness tends to be associated with lower inequality. Evidence of the Kuznets inverted U-shaped relationship between income per capita and inequality is also found in the data.

Going forward, large fiscal adjustments are expected to be required in many countries for a long time in order to reduce debt-to-GDP ratios to sustainable levels. For reasons of equity and also of political economy, fiscal adjustments that are viewed as being unfair are unlikely to be sustainable. It is therefore critical that the costs associated with fiscal consolidations and weaker growth be shared equitably throughout the economy.

Notes

The distributional impact of failing to adjust is beyond the scope of the paper. However, the impact on income distribution of a delay in fiscal adjustment could be even worse, if it results in an eventual debt crisis that forces a sudden, even greater fiscal adjustment, accompanied by a severe recession.

The paper focuses on the distributional effects of fiscal adjustments, but it is important to recognize the potential trade-off between equity and efficiency when designing redistributive policies. Redistributive tax and benefit systems can introduce economic inefficiencies with implications for long-term productivity and growth, as redistributive policies can influence the incentives for people to work, save, and invest. There is a large literature on the relationship between inequality and growth (besides the aforementioned papers, see also Alesina and Rodrik, 1994; Banerjee and Duflo, 2003; Bertola et al., 2005; Barro, 2008 and references therein).

In some emerging market economies, reforms of fuel and food subsidies are crucial to improving the equity impact of fiscal policy—evidence suggests that the rich often benefit the most from generalized subsidy programs. See Coady et al. (2010) for details.

For example, Jenkins et al. (2012) find that in the first 2 years following the crisis, there was not much immediate change in disposable income distribution in many advanced economies as a result of government support via tax and benefits, with real income levels declining throughout the income distribution.

These correlations (Figure 3) are for a sample of advanced, emerging, and low-income economies during the period of 1980–2009. Restricting to a sample of OECD economies yields similar results.

Subsequent to our paper, Ball et al. (2013) also examine the inequality effects of fiscal adjustment for 17 OECD countries over 1978–2009. Overall, their results are consistent with those of this paper including a similar range of the impact magnitude and the same conclusion that expenditure-based adjustments tend to worsen the inequality more than tax-based ones.

The analysis focuses on within-country income inequality and does not consider other dimensions of inequality in a broad term, such as inequality of opportunities and poverty or inequality among countries.

Following Agnello and Sousa (2014), we impose cross-equation restrictions on the coefficients of fiscal adjustment measures in the market income inequality equation (i.e., these coefficients are assumed to be zero) under the common assumption that the fiscal austerity measures (discretionary changes in taxes and spending) only affect disposable income (i.e., income after taxes and transfers), while the indirect effects on both market and disposable income are controlled for by income per capita, unemployment, and other variables that are included in both equations. Note that if each equation contains exactly the same set of regressors, the SUR is equivalent to the OLS and hence there will be no gain in efficiency. For a discussion on the estimation of a SUR in the unbalanced panel data, see BiØrn (2004).

The regressions results (e.g., the causal relationship between fiscal adjustment and inequality) may be subject to endogeneity and should be interpreted with caution. The causal relationship between fiscal adjustment and inequality is examined with a system generalized method of moments (SGMM) later (Appendix Table A1).

The Kuznets curve relationship implies that inequality exhibits an inverted U-curve as the economy develops: economic development (including shifts from agriculture to industry and services and adoption of new technologies) initially benefits a small segment of the population, causing inequality to rise. Subsequently, inequality declines as the majority of people find employment in the high-income sector. However, the existing evidence for the Kuznets curve is mixed (see Barro, 2008; Kanbur, 2000 and references therein).

For example, trade openness tends to exert downward pressure on the wage of low-skilled workers, increasing inequality. On the other hand, if openness has a positive effect on investment and growth so that the real incomes of the poorer groups in society also rise, this may enable these groups to invest in human capital and entrepreneurial activities, improving income distribution over the longer term.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is found to be associated with an increase in inequality (IMF, 2007). FDI inflows in emerging market and developing economies tend to increase the demand, and thus the wage premium, for skilled labor, whereas outward FDI in advanced economies tends to reduce the demand, and hence the wages, for lower-skilled labor. A related consideration is that trade openness may facilitate technology diffusion from advanced economies to emerging market and developing countries through FDI and imports of capital equipment (such as for information technology) as well as the international production network. In the receiving emerging market and developing countries, the new technologies tend to be more skill intensive than those in use before the liberalization of trade and FDI, which increases the demand for skilled labor and thus worsens income inequality. The fact that the earnings of highly skilled and highly educated workers have increased at the fastest rate in so many countries is also consistent with the view that higher international integration has introduced skill-biased technologies to the developing world.

Alternative sources were also used, including data on consolidations from Alesina and Ardagna (2010) for 17 OECD countries, and structural balance data from the IMF. For interesting discussions on the issues of identification of fiscal consolidation episodes, measurement of the size of consolidation, and estimation of short-term growth effects of consolidations, see Perotti (2011) and Alesina and Ardagna (2012) as well as IMF (2010b).

The CAPB is calculated by taking the actual primary balance—non-interest revenue minus non-interest spending—and subtracting the estimated effect of business cycle fluctuations on the fiscal accounts.

The sample country and period is dictated by the availability of data from Devries et al. (2011). In addition, given the magnitude of the recent global financial crisis, focusing on the period prior to it allows us to disentangle the distributional impact of consolidation itself from that of a large financial crisis and ensuing recession.

This is with respect to a baseline in which fiscal adjustment is not implemented and deficits continue to be financed without major disruptions. If the absence of fiscal adjustment leads to a fiscal crisis, with disruptive consequences for economic activity, income inequality could deteriorate even more. Our assumption that the coefficients of fiscal adjustment measures in the market income inequality equations are equal to zero are not rejected.

To put this in perspective, note that the average Gini coefficient for disposable income in the 17 OECD countries increased by about 2 percent over 10 years (between 1995 and 2005).

This seems to reflect the fact that large fiscal adjustments tend to be longer in duration and mostly spending based. Spending-based fiscal adjustment has been found to have more pronounced effects on inequality than tax-based adjustment. This is confirmed in the case study presented later in this paper.

However, the FE coefficient estimates (columns 10–12) turn out to be smaller in size and insignificant.

An international dollar is based on purchasing power parity exchange rates and has the same purchasing power as the U.S. dollar. Consumer price index inflation was also tried, but the resulting coefficients were not significant.

The methodology closely follows Cerra and Saxena (2008) and IMF (2010b). The least squares approach to estimate dynamic panel regression in the presence of country-fixed effects causes a dynamic panel bias due to the inevitable correlation between country-fixed effects and the lagged dependent variable when the time dimension of the panel (T) is small. Nickell (1981) derives a formula for the bias, showing that the bias approaches zero as T approaches infinity. The order of bias is O(1/T), which is small in our data with T = 32 and N = 17 (Judson and Owen 1999). As a robustness check, a system generalized method of moments (SGMM) is tried and the results are very similar as shown in Appendix Table A1.

Coefficients of the measure of fiscal adjustment or contraction and its two lagged terms are jointly significant at the conventional levels.

Results are closely similar when Gini coefficient or its log is used as the dependent variable in the dynamic panel regression. The Gini coefficient is employed here to facilitate interpretation of the chart.

The measure is a dummy variable taking a value of 1 in the year of a large fiscal consolidation or contraction and 0 otherwise, where a large fiscal consolidation is defined by Alesina and Ardagna (2010) to be larger than 1.5 percent of GDP. Thus, the result using this dummy variable is not directly comparable to that based on the consolidation measure (in percent of GDP) from Devries et al. (2011).

This magnitude is similar to that in Ball et al. (2011).

Many of these episodes took place as European Union member states attempted to meet the Maastricht criteria (i.e., the convergence criteria) for adoption of the euro as their currency.

On average, the duration and size of the seven spending-based consolidations were about 4 years and 6.8 percent of GDP (as measured by change in structural balance), compared to about 2 years and 3.2 percent of GDP in the case of the seven tax-based consolidations.

Asterisk indicates the countries included in the 17 OECD country sample, and † advanced economies.

References

Acemoglu D., 2003, “Cross-Country Inequality Trends,” The Economic Journal, Vol. 113, pp. F121–F149.

Agnello, L. and R. M. Sousa, 2014, “How Does Fiscal Consolidation Impact on Income Inequality?” Review of Income and Wealth, Vol. 60, No. 4, pp. 702–706.

Alesina, A. and S. Ardagna, 1998, “Tales of Fiscal Adjustments,” Economic Policy, Vol. 13, No. 27, pp. 487–545.

Alesina, A. and S. Ardagna, 2010, “Large Changes in Fiscal Policy: Taxes versus Spending,” in Tax Policy and the Economy, Vol. 24, ed. by J. R. Brown. Chicago: National Bureau of Economic Research, The University of Chicago Press.

Alesina, A. and S. Ardagna, 2012, “The Design of Fiscal Adjustments,” Unpublished Working Paper, Harvard University.

Alesina, A. and D. Rodrik, 1994, “Distributive Politics and Economic Growth.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 109, No. 2, pp 465–490.

Asian Development Bank, 2007, “Inequality in Asia,” In Key Indicators 2007: Inequality in Asia, Asian Development Bank, Manila.

Atkinson, A. B. and A. Brandolini, 2001, “Promise and Pitfalls in the Use of ‘Secondardy Data-Sets: Income Inequality in OECD Countries as a Case Study,” Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 39, No. 3, pp. 771–799.

Atkinson, A. B. and S. Morelli, 2011, “Inequality and Banking Crises: A First Look,” UNDP Human Development Research Paper 2011/06.

Autor, D., L. Katz, and A. Krueger, 1998, “Computing Inequality: Have Computers Changed the Labor Market?” Quarterly Journal of Economics, pp. 1169–1213.

Avram, S., F. Figari, C. Leventi, H. Levy, J. Navicke, M. Matsaganis, E. Militaru, A. Paulus, O. Rastringina, and H. Sutherland, 2013, “The Distributional Effects of Fiscal Consolidation in Nine Countries,” EUROMOD Working Paper No. EM 2/13, Institute of Social and Economic Research, Essex University, Essex.

Ball, L., D. Leigh, and P. Loungani, 2011, “Painful Medicine,” Finance and Development, Vol 49, International Monetary Fund.

Ball, L., D. Furceri, D. Leigh, and P. Loungani, 2013, “The Distributional Effects of Fiscal Austerity,” Manuscript, International Monetary Fund.

Banerjee, A.V. and Duflo, E. 2003, "Inequality and Growth: What Can the Data Say?" Journal of Economic Growth, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 267–299.

Barones, S. J. and M. J. Alvarez-Rivadulla, 2007, “Standardized Income Inequality Data for Use in Cross-National Research,” Socio logical Inquiry, Vol. 77, No. 1, pp. 3–22.

Barro, R., 2008, “Inequality and Growth Revisited,” Asian Development Bank Working Paper Series on Regional Economic Integration, No. 11, January.

Bastagli, F., D. Coady, and S. Gupta, 2012, “Income Inequality and Fiscal Policy,” IMF, Staff Discussion Note, 12/08, International Monetary Fund, Washington.

Beck, N. and J. Katz, 1995, “What to Do (and Not to Do) with Time-Series Cross-Section Data, American Political Science Review, Vol. 89, No. 3, pp. 634–647.

Benedek, D., R. de Mooij, M. Keen, and P. Wingender, 2015, “Estimating VAT Pass Through,” IMF Working Paper 15/214, International Monetary Fund, Washington.

Berg, A., J. D. Ostry, and J. Zettelmeyer, 2011, “What Makes Growth Sustained?” European Bank for Reconstruction and Development Working Paper No. 33, July.

Bertola, G., Foellmi, R., and Zweimüller, J., 2005, Income Distribution in Macroeconomic Models. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

BiØrn, X., 2004, “Regression Systems for Unbalanced Panel Data: A Stepwise Maximum Likelihood Procedure,” Journal of Econometrics, Vol. 122, No. 2, pp. 281–291.

Bulir, A. (1998), “Income Inequality: Does Inflation Matters?” IMF Working Paper 98/7, International Monetary Fund, Washington.

Cerra, V. and S. Saxena, 2008, “Growth Dynamics: The Myth of Economic Recovery,” American Economic Review, Vol. 98, No. 1, pp. 439–57.

Chu, K.-Y., H. Davoodi, and S. Gupta, 2004, “Income Distribution and Tax and Government Social-Spending Policies in Developing Countries,” in Inequality, Growth, and Poverty in an Era of Liberalization and Globalization, ed. by Giovanni Andrea Cornia. New York: Oxford University Press.

Clements, B., R. de Mooij, S. Gupta, and M. Keen, 2015, Inequality and Fiscal Policy. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Coady, D., R. Gillingham, R. Ossowski, J. Piotrowski, S. Tareq, and J. Tyson, 2010, “Petroleum Product Subsidies: Costly, Inequitable, and Rising” IMF Staff Position Note SPN/10/05, International Monetary Fund, Washington.

Cubero, R. and I. V. Hollar, 2010, “Equity and Fiscal Policy: The Income Distribution Effects of Taxation and Social Spending in Central America,” IMF Working Paper, 10/112, International Monetary Fund, Washington.

Deininger, K. and L. Squire, 1996, “A New Data Set Measuring Income Inequality,” World Bank Economic Review, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 565–591.

De Gregorio, J. and J. Lee, 2002, “Education and Income Inequality: New Evidence From Cross-Country Data,” Review of Income and Wealth, Vol. 48, No. 3, pp. 395–416.

Devries, P., J. Guajardo, D. Leigh, and A. Pescatori, 2011, “A New Action-based Dataset of Fiscal Consolidation,” IMF Working Paper No. 11/128, International Monetary Fund, Washington.

Driscoll, J. C. and A. C. Kraay, 1998, “Consistent Covariance Matrix Estimation with Spatially Dependent Panel Data,” Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 80, pp. 549–560.

Easterly, W. and S. Fisher, 2001, “Inflation and the Poor,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Vol. 1, pp. 159–178.

Easterly, W., 2007, “Inequality Does Cause Underdevelopment: Insights from a New Instrument,” Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 84, No. 2, pp. 755–776.

EU KLEMS, 2012, EU KLEMS Database, EU KLEMS.

European Commission, 2012, Eurostat database, European Commission.

Furceri, D., J. T. Jalles, and P. Loungani, 2015, “Fiscal Consolidation and Inequality in Advanced Economies: How Robust is the Link?, “in Inequality and Fiscal Policy, ed. by B. Clements, R. de Mooij, S. Gupta and M. Keen. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Gemmell, N. and O. Morrissey, 2005, “Distribution and Poverty Impacts of Tax Structure Reform in Developing Countries: How Little We Know,” Development Policy Review, Vol. 23, No. 2, pp. 131–144.

Giavazzi, F. and M. Pagano, 1996, “Non-Keynesian Effects of Fiscal Policy Changes: International Evidence and the Swedish Experience,” Swedish Economic Policy Review, Vol. 3, pp. 67-103.

Glaeser, E. 2010, “Does Economic Inequality Cause Crises?” The New York Times (December 14, 2010).

Goñi, E., J. H. López, and L. Servén, 2008, “Fiscal Redistribution and Income Inequality in Latin America,” Policy Research Working Paper 4487.

IMF, 2007, “Globalization and Inequality,” World Economic Outlook, pp. 31–65.

IMF, 2010a, “Appendix 3. Fiscal Adjustment and Income Distribution in Advanced and Emerging Economies,” Fiscal Monitor (November), pp. 94–98.

IMF, 2010b, “Will It Hurt? Macroeconomic Effects of Fiscal Consolidation,” World Economic Outlook (October).

IMF, 2012, World Economic Outlook Database, International Monetary Fund.

IMF-Fiscal Affairs Department, 2012, Fiscal Affairs Department Database, International Monetary Fund.

Jenkins, S. P., A. Brandolini, J. Micklewright, and B. Nolan, 2012, The Great Recession and the Distribution of Household Income. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jorgenson, D. and K. Vu, 2007, “Information Technology and the World Growth Resurgence,” German Economic Review, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 125–145.

Joumard, I., M. Pisu, and D. Bloch, 2012, “Less Income Inequality and More Growth–Are They Compatible?: Part 3. Income Redistribution via Taxes and Transfers Across OECD Countries,” OECD Economic Department Working Papers No. 926.

Judson, R. and A. Owen, 1999, “Estimating Dynamic Panel Data Models: A Guide for Macroeconomists,” Economics Letters, Vol. 65, No. 1, pp. 9–15.

Kanbur, R., 2000, “Income Distribution and Development,” in Handbook of Income Distribution, ed. by A.B. Atkinson and F. Bourguignon, pp. 791–841.

Keen, M., 2014, “Targeting, Cascading, and Indirect Tax Design,” Indian Growth and Development Review, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 181–201.

Knight, J. B. and R. Sabot, 1983, “Educational Expansion and the Kuznets Effects,” American Economic Review, Vol. 73, pp. 1132–1136.

Krugman, P., 2008, “Trade and Wages, Reconsidered,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Vol. 2, pp. 103–137.

Lustig, N., 2015, “The Redistributive Impact of Government Spending on Education and Health: Evidence from 13 Developing Countries in the Commitment to Equity Project,” in Inequality and Fiscal Policy, ed. by S. Gupta, M. Keen, B. Clements and R. de Mooij. Washington: International Monetary Fund.

Martinez, R., L. Ayala, and J. Ruiz-Huerta, 2001, “The Impact of Unemployment on Inequality and Poverty in OECD Countries,” Economics of Transition, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 417–447.

Martinez-Vazquez, J., B. Moreno-Dodson, and V. Vulovic, 2012, “The Impact of Tax and Expenditure Policies on Income Distribution: Evidence from a Large Panel of Countries,” Review of Public Economics, Vol. 200, No. 4/2012, pp. 95–130.

Meschi, E. and M. Vivarelli, 2007, “Globalization and Income Inequality,” IZA Discussion Paper No.2958, July.

Muinelo-Gallo, L. and O. Roca-Sagalés, 2011, “Economic Growth and Inequality: The Role of Fiscal Policies,” Australian Economic Papers, Vol. 50, No. 2–3, pp. 74–97.

Muinelo-Gallo, L. and O. Roca-Sagalés, 2013, “Joint Determinants of Fiscal Policy, Income Inequality and Economic Growth,” Economic Modelling, Vol. 30, pp. 814–824.

Mulas-Granados, C., 2005, “Fiscal adjustments and the short-term trade-off between economic growth and equality,” Revista de Economia Pública, Vol. 172, No. 1, pp. 61–92.

Nickell, S., 1981, “Biases in Dynamic Models with Fixed Effects,” Econometrica, Vol. 49, No. 6, pp. 1417–1426 (November).

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), 2011, “Divided We Stand: Why Inequality Keeps Rising” (Paris).

OECD, 2012, “Income Inequality and Growth: The Role of Taxes and Transfers,” OECD Economics Policy Notes, No.9 (January).

Paulus, A., M. Čok, F. Figari, P. Hegedüs, N. Kump, O. Lelkes, H. Levy, C. Lietz, S. Lüpsik, D. Mantovani, L. Morawski, H. Sutherland, P. Szivos, and Andres Võrk, 2009, “The Effects of Taxes and Benefits on Income Distribution in the Enlarged EU,” Working Paper N. 8/09, EUROMOD.

Perrotti, R., 2011, “The “Austerity Myth”: Gain Without Pain?” in Fiscal Policy after the Financial Crisis, ed. by A. Alesina and F. Giavazzi. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ramey, V. A. and M. D. Shapiro, 1998, “Costly Capital Reallocation and the Effects of Government Spending,” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, Vol. 48, No. 1, pp. 145−194.

Ramey, V. A., 2011, “Identifying Government Spending Shocks: It's All in the Timing,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 126, No. 1, pp. 1–50.

Rawdanowicz, L., E. Wurzel, and K. Christensen, 2013, “The Equity Implications of Fiscal Consolidation,” OECD Economics Department Working Papers N. 1013, OECD Publishing.

Reinhart, C. and K. Rogoff, 2011, “From Financial Crash to Debt Crisis,” American Economic Review, Vol. 101, No. 5, pp. 1676–1706.

Romer C. D. and D. H. Romer, 2010, “The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes: Estimates Based on a New Measure of Fiscal Shocks,” American Economic Review, Vol. 100, No. 3, pp. 763–801.

Rothstein, J., 2010, “Is the EITC as Good as an NIT? Conditional Cash Transfers and Tax Incidence,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 177–208.

Smeeding, T. M., 2005, “Public Policy, Economic Inequality, and Poverty: The United States in Comparative Perspective,” Social Science Quarterly, Vol.86, No. S1, pp. 955–983.

Solt, F., 2009, “Standardizing the World Income Inequality Database,” Social Science Quarterly, Vol. 90, No. 2, pp. 231–242 (2012 update).

Solt, F., 2012, “Standardized World Income Inequality Database, Version 3.1”.

UNU-WIDER, 2008, “World Income Inequality Database, version 2.0c, May 2008,” http://www.wider.unu.edu/research/Database/en_GB/database.

Woo, J., 2011, “Growth, Income Distribution and Fiscal Policy Volatility,” Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 96, No. 2, pp. 289–313.

World Bank, 2012, World Development Indicators CD-ROM, World Bank.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

*Jaejoon Woo is Chief Korea Economist at the Bank of America Merrill Lynch and also an Associate Editor of International Economic Journal. He was a senior economist at the IMF when the paper was written. His work focuses on growth, fiscal policy, inequality, and macroeconomics. He received his Ph.D. in Economics from the Harvard University; his email address is jaejoon.woo@baml.com. Elva Bova is an Economist at the European Commission. Her work focuses on fiscal policy and macroeconomics. She received her Ph.D. in Economics from the University of London; her email address is elvabova@gmail.com. Tidiane Kinda is Special Assistant to the Director in the Asia and Pacific Department of the IMF. His work focuses on international economics, public finance, and income inequality. He received his Ph.D. in Economics from CERDI Université d’ Auvergne; his email address is tkinda@imf.org. Y. Sophia Zhang is an Economist in the IMF. Her work focuses on public finance. She received her Ph.D. in Economics from the University of California at Los Angeles; her email address is yzhang@imf.org. The authors would like to thank the editor, two anonymous referees, Martin Cerisola, David Coady, Carlo Cottarelli, Xavier Debrun, Markus Eller, Greetje Everaert, Lorenzo Forni, Davide Furceri, Phil Gerson, Martine Guerguil, Sanjeev Gupta, Mulas Granados, Frigyes Heinz, Andrea Lemgruber, Laura Jaramillo Mayor, Leandro Medina, Tigran Poghosyan, Marcos Poplawski Ribeiro, Serges Saksonovs, Andrea Schaechter, Bahrom Shukurov, Yan Sun, Anke Weber, and participants in IMF seminars and Villa Mondragone International Economic Seminar, Rome, Italy for helpful comments and discussions. Petra Dacheva and Carsten Jung provided excellent research assistance. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix A: Description of Data and Sample Country List

Appendix A: Description of Data and Sample Country List

Measures of Income Inequality

-

(1)

Gini coefficients for disposable and market income, Solt (2009; 2012 update)

-

(2)

Gini coefficients for disposable income (alternative dataset), compiled by the authors using data from World Income Inequality Database (2008), World Bank’s PovcalNet (2012), Eurostat (2012), and national sources

-

(3)

Labor income share, EU KLEMS Database (2012)

-

(4)

Ratios of top to bottom income shares (by quintile or decile), data from World Income Inequality Database (2008), PovcalNet (2012), Eurostat (2012), and national sources

Other Variables

-

(1)

Real GDP per capita (in log), IMF’s World Economic Outlook (2012)

-

(2)

Average years of schooling of population of age over 15 (in log), Barro and Lee (2010).

-

(3)

Trade openness (percent of GDP), World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI) (2012).

-

(4)

CPI Inflation rate (log of (1 + π)), WDI (2012).

- (5)

-

(6)

Information technology (IT) capital share of total capital stock, Jorgenson and Vu (2007).

-

(7)

Ratio of direct to indirect taxes, IMF/Fiscal Affairs Department Database (2012).

-

(8)

Cyclically adjusted individual and corporate income taxes and cyclically adjusted indirect tax, IMF/Fiscal Affairs Department Database (2012).

-

(9)

Government spending (wage bill, social benefits, subsidies, capital spending), IMF/Fiscal Affairs Department Database (2012).

-

(10)

Fiscal consolidation (spending and tax measures), percent of GDP, Devries et al. (2011).

-

(11)

Fiscal consolidation episodes, Alesina and Ardagna (2010).

-

(12)

Banking crisis incidence, Reinhart and Rogoff (2011).

Sample Country List Footnote 30

48 Advanced and Emerging Economies: Argentina, Australia*†, Austria*†, Belgium*†, Bulgaria, Brazil, Canada*†, Chile†, Colombia, Czech Republic†, Denmark*†, Finland*†, France*†, Germany*†, Greece†, Hong Kong, Hungary†, Iceland†, Indonesia, Ireland*†, Israel, Italy*†, Japan*†, Korea†, Lithuania, Luxembourg†, Latvia, Malaysia, Netherlands*†, Norway†, New Zealand†, Peru, Poland†, Portugal*†, Romania, Russia, Singapore, Slovak†, Slovenia†, South Africa, Spain*†, Sweden*†, Switzerland†, Thailand, Turkey†, Ukraine, United Kingdom*†, and United States*†