Abstract

Capital controls remain a common approach to capital flows management. Meanwhile, the IMF has revised its position regarding selective use capital controls. However, the effects of granular variation in capital controls by asset category and direction of flow are not fully documented. Using a new dataset on capital control measures, I find that countries using capital controls on short-term capital inflows receive a higher level of direct investment inflows, and that this effect is decreasing in the country’s growth rate. I show that this result is consistent with the interpretation that the capital control serves as a signal of stability in slower-growing countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

For decades, capital controls have been a controversial policy decision. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the position of the IMF was clear: liberalize capital markets—remove capital controls. Nevertheless, volatile capital flows and the subsequent debt crises of the 1990s have challenged the IMF’s position. Surges in short-term capital flows have been observed to invoke systemically destabilizing volatility, contributing to the 1994 Tequila Crisis in Mexico, the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, and the 1998 Russian Financial Crisis.Footnote 1 Many countries have since used capital controls. Well-studied examples are Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Malaysia.Footnote 2 The outcomes for capital controls are mixed. There is a general consensus that capital controls are effective at modifying the composition of capital flows, but not for stemming the volume of capital flows.Footnote 3 During the 1990s, the IMF suggested the use of controls on inflows for just 2 of 27 episodes of surging inflows (IMF Independent Evaluation Office 2005). Confronted with years of experience with volatile external capital flows, the IMF faced a need to revise its policy guidance with respect to capital controls. In 2011, the IMF released a comprehensive research series on capital flows policy guidance that concluded with the Institutional View on the Liberalization and Management of Capital Flows in which the IMF recognizes that in certain circumstances, capital flow management measures can be useful. They should not however substitute for warranted macroeconomic adjustmentFootnote 4 (Arora et al. 2013).

To the extent that capital controls can mitigate risks attributed to external capital flows, controls on short-term capital inflows are of particular interest. The maturity structure of short-term capital flows enables sustained surges in inflows to be followed by a sudden reversal with a shift in market conditions. Such “hot money” jumps market to market seeking high returns. The volatility of short-term capital flows can destabilize financial markets that are underdeveloped. Moreover, capital controls on short-term capital inflows are commonly used. Since 2007, more than 1 in 2 economies have used restrictions on short-term capital inflows, and more than 1 in 4 economies have added restrictions in the same time.Footnote 5 With controls on short-term capital inflows persistent if not growing in use, it is worthwhile to ask what an economy gives up by imposing this particular capital control? The effects of granular variation in capital controls by asset category and direction of flow are not fully documented. This paper focuses specifically on the relationship between capital controls on short-term capital inflows and direct investment inflows; does an economy give up its direct investment in using a capital control on short-term capital inflows? Further, I consider the conditions under which capital controls on short-term capital inflows might be useful or harmful for direct investment. This will be important for policymakers reviewing the use of capital controls in the case that the policymaker values the level of direct investment inflows.

Using a new dataset by Fernández et al. (2015) with information on capital control measures covering 100 countries over the years 1995–2015 and panel data fixed effects regression, I find that countries which use capital controls on short-term capital inflows receive a higher level of direct investment inflows. Further, I find that this effect is decreasing in the country’s per capita growth rate. Thus, lower (higher) growth countries which add restrictions on short-term capital inflows expect their direct investment inflows to increase (decrease), all else equal. This result is consistent with Cordella (2003), where capital control policy increases the expected return on investment, thereby increasing capital inflows. I test this relationship in alternative specifications, including instrumental variables panel data random effects regression and Arellano–Bond generalized method of moments. Policy questions concerning capital flows carry significant implications for reverse causality – this is addressed in the paper using the alternative specifications and I confirm that the results hold. Finally, I find evidence that capital controls on short-term capital inflows serves as a signal of stability to attract investors to lower-growth countries.

The essay proceeds as follows. The next section presents a brief literature review. Following the literature review is a discussion on the theoretical background which forms the basis for the empirical work. Next, I present some facts about the data used including the dataset used as the capital controls index. The following section contains the results of the baseline model. After discussing the baseline results, I re-estimate the baseline model using instrumental variables and then discuss sensitivity analysis. The final section concludes.

Literature Review

Capital flows management is an important branch of the international economics literature. The Research Department at the IMF has published several working papers that serve as the analytical basis for the policy guidance series on capital flows discussed in introduction.Footnote 6 The IMF’s revised policy guidance recognizes the capacity for capital controls to address macroeconomic and financial stability concerns in the face of inflow surges, only after all macroeconomic and exchange rate policy options have been exhausted (Ostry et al. 2011). The IMF’s revised position on capital controls highlights the substantial trade-offs that a policymaker must consider when evaluating a capital control. These trade-offs remain unsettled in the literature on many of the objectives that have been associated with capital controls. Forbes et al. (2015) find little support that capital controls are effective in any of 15 objectives. Forbes et al. (2015) however do not consider restrictions at the granular level like short-term capital inflows, nor do they study the influence of capital controls on direct investment. Several studies have found that capital controls push the maturity composition of external capital flows toward more long-term flows such as direct investment, but do not have an effect on the volume of external capital flows (Montiel and Reinhart 1999; Carlson and Hernandez 2002; Alfaro et al. 2005). Many studies have also found that capital controls improve growth resilience or reduce the vulnerability to crisis (Qureshi et al. 2011; Gupta et al. 2007; Edwards and Rigobon 2009; Pyun and An 2016), but there is evidence that this comes at the expense of efficiency losses and market discipline (Cardarelli et al. 2010; Forbes 2005b). Finally, there is an important branch of this literature which has looked at the costs of capital controls at the firm/investor level, where lower returns, higher cost of firm financing, and lower investment are significant (Alfaro et al. 2017; Forbes 2005b; Forbes et al. 2016).

The contribution of this paper adds to a subset of papers which have studied the economic consequences of capital controls on particular asset categories as opposed to broadly defined capital control indices (see e.g., Eichengreen and Rose 2014; Alfaro et al. 2017; Asiedu and Lien 2004). In a closely related paper, Dell’Erba and Reinhardt (2015) show using an event study that restrictions on short-term debt flows decrease the likelihood of banking debt surges but increase the likelihood of financial sector foreign direct investment surges. The results presented here indicate that slower-growing countries with capital controls on short-term capital inflows receive higher levels of foreign direct investment. This result is similar to Dell’Erba and Reinhardt (2015) and is consistent with Cordella (2003), where foreign lenders in a theoretical economy find it profitable to invest in an emerging market if and only if the emerging government imposes taxes on short-term capital inflows. In Cordella (2003), the policy imposed on short-term capital inflows can prevent bank runs, increasing expected returns to investing and in turn increasing the volume of capital flows.

Theoretical Background

The focus of this paper is a country-level analysis on the response of direct investment to capital controls on short-term capital inflows. In “Appendix 1”, I extend the framework in Magud et al. (2011) to characterize the relationship between long-term inflows and a capital control. Magud et al. (2011) use the portfolio balance approach to identify the optimal behavior of short-term capital inflows in response to a capital control on short-term capital inflows. An extension naturally follows, beginning with the optimal portfolio allocation with respect to long-term inflows. In the second subsection of the theoretical framework section in “Appendix 1”, I establish the optimal behavior of long-term inflows in response to a capital control on short-term inflows.

The conditions that describe the optimal behavior of long-term capital inflows when the economy is subject to a capital control on short-term capital inflows depend on the elasticity of long-term flows to total flows. Specifically, if the elasticity of direct investment to total inflows is greater than one, a capital control on short-term capital inflows increases the level of direct investment. However, if the elasticity of direct investment to total inflows is less than one, a capital control on short-term inflows leads to a lower level of direct investment. This means that the way direct investment responds to a capital control on short-term capital inflows may differ for some countries – increasing in some, decreasing in others. The value that this elasticity will ultimately take is exogenous to the model.

The objective of this paper is to determine, on average, how direct investment responds to a capital control on short-term capital inflows. I will also test this whether this relationship is different for countries that are growing slower or faster. In this way, an objective of this paper is to test the average sign of this elasticity.

Data

I use annual data on net foreign direct investment inflows from 1995 to 2015 for 100 countries. Data on the determinants for direct investment are sourced from World Bank’s World Development Indicators and the International Monetary Fund’s International Financial Statistics. Additional data are obtained in the Gurevich and Herman (2018) Dynamic Gravity Dataset. The data for capital controls are provided by the new dataset presented in Fernández et al. (2015). Data on the level of institutional quality are provided by the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World database, which measures the degree to which the policies and institutions of countries are supportive of economic freedom. Additional measures on institutional quality are obtained from the World Governance Indicators project, which are published with the World Development Indicators by World Bank. Finally, data for instrumental variables are obtained on legal origins from Porta et al. (1998), on central bank independence from Garriga (2016), and political institutions from Cruz et al. (2016a). A complete list of the variables with their definitions and their sources is included in “Appendix 2”. In the following, I will provide a brief description of the Fernández et al. (2015) dataset and how it is used in this paper, as well as some facts regarding the data in general.

Capital Control Measures

The capital control measures used in this paper originate in a new dataset made available by Fernández et al. (2015). Using information in the IMF’s Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions (AREAER), Fernández et al. (2015) build on a dataset presented in Schindler (2009). Fernández et al. (2015) further disaggregate the capital control measures by 10 distinct capital asset categories and by the direction of flows for 100 countries from 1995 to 2015.Footnote 7 The capital control measures draw from the de jure information contained in the IMF’s AREAER. De jure information in this context is correlated with official rules and practices, referring to the state of affairs in accordance with the law. In contrast, de facto information would measure actual outcomes, the extent to which rules and practices are enforced, independent of their official status.

Capital control measures by definition restrict capital transactions on the basis of residency, limiting capital mobility between residents and non-residents. There exist two types of capital inflow transactions and two types of capital outflow transactions on which most capital controls can be imposed. Table 1 distinguishes each type of transaction according to the residency of the initiating party and the direction of flow. Transactions that result in inflows or outflows can be initiated by a resident or non-resident. For example, the transaction recorded as a purchase locally by non-resident is a non-resident transaction and a capital inflow. An example of this transaction would be a Mexican firm purchasing a US bond, where the USA is the home country.

Fernández et al. (2015) use the narrative description in the AREAER to determine whether a restriction on any of the four transactions in Table 1 is present. Additionally, Fernández et al. (2015) repeat this procedure across 10 capital asset categories, including short-term capital (money market instruments). With this information, I build a set of capital control dummies for money market inflows and direct investment inflows in addition to an aggregate capital control index. The first money market inflows dummy variable equals one in a given year when a country only uses one of the restrictions in the second column of Table 1: either a restriction on a sale or issue abroad by a resident or a restriction on a local purchase by a non-resident. The second money market inflows dummy variable equals one in a given year when a country uses restrictions on both transactions in the second column of Table 1. I create a dummy variable for capital controls on direct investment inflows, and an aggregate control index over the remaining 8 capital asset categories, excluding money market instruments and direct investment.Footnote 8 The event that a country uses zero restrictions on inflows transactions serves as the numeraire for each asset-specific set of dummy variables.

While some countries have placed restrictions on money market inflows and money market outflows at the same time, these instruments have objectives which are theoretically opposing. Forbes et al. (2015) observe that increasing controls on inflows and decreasing controls on outflows are policy decisions that are meant to address strong net capital inflows, currency appreciation, rapid credit growth, and the related vulnerabilities. Likewise, removing controls on inflows but increasing controls on outflows theoretically addresses sudden stops, currency depreciation, or a contraction in credit. What’s more, restrictions on inflows help to prevent (rather than to respond to) crises, and they are considered to decrease uncertainty and increase transparency by providing creditors information regarding transaction costs at the beginning of a transaction (Ocampo and Stiglitz 2008). Finally, capital controls on outflows have been associated with meeting budgetary needs through financial repression. This last objective is not associated with capital controls on inflows, but is observed to have contributed to the unfavorable perception of capital controls, generally (Ghosh and Qureshi 2016). As a result of the opposing policy objectives for capital controls in the two different directions, I focus on controls on money market inflows.

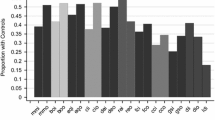

Using the detailed nature of the Fernández et al. (2015) dataset, I can determine the incidence of capital control restrictions specific to money market inflows. Following Table 1, a country can impose zero, one, or two restrictions on money market inflows. Three trends are evident in Fig. 1. The country-level incidence for each of the three possible quantities of restrictions used on money market inflows over the years 1995–2015 is plotted in Fig. 1. Countries that use either one or two restrictions tend to assume near equal parts of just less than half the sample, while countries that use no restrictions make up the remaining lion’s share. Second, the importance of money market capital controls increases in the late 1990s in the wake of several debt crises. The frequency of money market capital controls decreases slightly before the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 and increases again following the Global Financial Crisis. The number of countries that use no restrictions falls from 66 in 1995 to 56 in 1997, grows to 66 in 2006, but then steadily falls to 58 in 2013. The number of countries that use one of the restrictions has fallen since the financial crisis, from 23 countries in 2008 to 20 countries in 2015. However, the country-level incidence of two restrictions is steadily increasing following the global financial crisis from 16 countries in 2008 to 22 countries in 2015.

The relative frequency of the three levels of money market inflows capital controls is stable over the duration of the sample period. Countries that have zero restrictions on money market inflows consist approximately of three-fifths of the sample, and countries that have one or two restrictions make up about one-fifth of the sample for the duration of the sample period. However, the stability in relative frequency masks a significant temporal variation at the country level. In each year from 1995 to 2015, there exists at least one country adding restrictions on money market inflows and one country removing restrictions from money market inflows. Figure 2 is a histogram with the frequency of countries adding and removing controls in each year of the sample. There appears to be more countries changing controls in the beginning of the period than the end of the period, with the number of countries removing controls in much higher frequency in the beginning of the sample period. However, in any given year over the sample period, there are more countries adding restrictions than removing restrictions, with 11 years that have more countries adding restrictions versus 6 years that have more countries removing restrictions. A caveat of this illustration is that the dynamics in the various quantities of restrictions are pooled. In the subsection of “Appendix 3” on data visualization, the histogram in Fig. 4 breaks down the frequencies respecting each of the three ways a country can add restrictions and the three ways a country can remove restrictions.

Summary Statistics

The dependent variable in the baseline model of this paper is the level of net direct investment inflows (FDI) as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP). Measuring FDI and its determinants as a percentage of GDP provides cross-country comparability for these variables in a panel data setting. The conventional definition of foreign direct investment is cross-border investment made by a resident in one economy with the objective of establishing a lasting interest in a firm which resides in an economy other than that of the direct investor. Lasting interest indicates that the direct investor owns at least 10% of the voting power of the firm, which is meant to signal a long-term investment relationship (OECD 1998). Direct investment is expected to outlive cyclical movements in output, and FDI is robust to economic volatility and short-term movements in interest rates (Ramey and Ramey 1995). FDI tends not to be associated with the characteristics of “hot money,” capital flows that lead to surges and sudden stops (Reinhart and Reinhart 2009). For these reasons and the notion that FDI crowds in domestic investment, policymakers particularly value the level of foreign direct investment.

AverageFootnote 9 foreign direct investment and short-term debt flows for 1995–2015 are plotted in Fig. 3. The countries have been separated into two groups. The first group consists of countries that have capital controls on money market inflows for the entire period or have introduced the controls by 2007 and are left in place for the remainder of the sample period. The second group consists of countries that have never had capital controls in place or have removed them before 2007 and never introduced them again. The first group of countries is represented by the solid line in Fig. 3a, b, and the second group is represented by the dashed line. The first group has markedly higher direct investment than the second group for almost the entirety of the sample period. The first group of countries—those using controls the entire period or have introduced by controls by 2007—also tends to have higher net flows on external short-term debt. Net flows on short-term debt appear more volatile than net foreign direct investment, as expected. Average direct investment reaches a high of about 4% of GDP in 1999 and again in 2007 before the Global Financial Crisis, while average net flows on external short-term debt reach a high of 2.5% in 2010 during the height of the Federal Reserve’s unconventional monetary policy program. While the two groups track each other more closely in Fig. 3b, this could be evidence of reverse causality. Reverse causality is a principal objective of this paper and is addressed in the instrumental variables and sensitivity analysis sections.

Table 2 provides the summary statistics for the continuous variables used in this study, including the determinants of annual foreign direct investment inflows according to the baseline specification. There is a large set of literature on the determinants of foreign direct investment. The determinants chosen here follow research relevant for external factors affecting FDI flows. Eicher et al. (2012) use Bayesian model averaging to identify, in probabilistic terms, which determinants are the most important for direct investment inflows. Alfaro et al. (2008) examine determinants of capital flows with an emphasis on the level of institutional quality. Blonigen (2005) provides a comprehensive survey on the determinants of direct investment. These three studies jointly identify trade effects, factor endowments, exchange rates, FDI frictions, institutions, the growth rate, and infrastructure as important determinants for foreign direct investment.

Trade effects follow an important motivation for FDI: export substitution to a host country. From the prospective of the host country, this is import substitution. Countries with larger import markets are expected to attract more FDI. The size of a country’s capital endowment also attracts more FDI (Lucas 1990; Bergstrand and Egger 2007). The capital endowment is captured by gross fixed capital formation. Infrastructure is closely tied to a direct investor’s expected return to investment. Strong infrastructure,Footnote 10 measured by the rate of telephone subscriptions, decreases a firm’s transaction costs, increasing the expected return on investment. Foreign direct investment is expected to be increasing in the growth rate, as firms are more likely to establish a stake in countries where a higher future growth rate is reasonably expected (Carlson and Hernandez 2002). Additionally, direct investment is expected to decrease with the appreciation of the exchange rate. To the extent that a large part of foreign direct investment the result of supply chain dynamics, investors avoid economies whose export sectors are weakened by strong currencies (McKinnon 1999). Blonigen (2005) and Eicher et al. (2012) find that legal institutions and property rights as well as control of corruption are the most important dimensions in terms of institutional quality for FDI. Finally, to capture FDI frictions, I follow Alfaro et al. (2008) with a measure called distantness that reflects how remote or distant a country may be from the center of economic activity.

The level of net foreign direct investment inflows averages between 2.4% and 3.4% for the sample. The substantial cross-sectional variation (country-to-country) is evident in the ranges (as measured by the distance between the minimum and maximum values) of the variables in Table 2. This is expected in a sample of 100 countries. The large standard deviations of FDI, telephone lines, and the growth rate give very large coefficients of variation adding to the evidence on the substantial cross-sectional variation in the sample used here.

Empirical Analysis

Baseline Model

As Fig. 1 indicates, there is an increase in the number of countries that use capital controls on money market inflows starting in 2007. More than 1 in 2 economies have used restrictions on money market inflows since 2007, and more than 1 in 4 have added restrictions in the same time. Motivated by the increasing frequency of money market capital controls and their potential cost (see, e.g., Cardarelli et al. 2010; Forbes 2005a, b), I use panel data fixed effects regression in this section to study the relationship between direct investment inflows and the use of money market inflows capital control policy. Specifically, I ask does an economy give up its direct investment in using a capital control on money market inflows?

The baseline regression in Table 3 is a panel data fixed effects regression, and the dependent variable is foreign direct investment inflows as a percentage of gross domestic product (FDI). This measure of investment as the dependent variable effectively provides cross-country comparability in a panel data setting. To investigate the relationship between FDI and capital controls, I regress dummy variables for money market capital control policy on FDI. I also test this relationship with an aggregate capital control index. I estimate a panel data fixed effects specification for the determinants of direct investment inflows:

In Eq. 1, FDI\(_{it}\) is foreign direct investment inflows as a percent of gross domestic product for a country i in year t. The determinants of FDI are included in the vector \(\varvec{x}_{it}\). The vector \(\varvec{c}_{it}\) contains the capital control restrictions which are the feature component. In addition, the variable \(d_{it}\) represents the dummy variable for the capital control on direct investment inflows. Finally, \({\text {PCG}}_{it}\) is the per capita growth rate, \(\alpha _{i}\) are the country fixed effects, and \(\lambda _{t}\) are the year fixed effects.

Following Table 1, the set of capital controls in \(\varvec{c}_{it}\) are the capital controls on money market inflows MMI1 and MMI2 that track whether a country has one restriction or both restrictions on money market inflows in a given year. Countries with no restrictions serve as the numeraire. The determinants of direct investment are included in the baseline model to determine whether direct investment changes as the result of money market capital controls or otherwise. An interaction term between money market capital controls and the per capita growth rate is included to capture the individuality in the capital control prescription. The interaction will reveal how direct investment responds to policy variation in combination with the expected local return on investment. I also test this relationship using an aggregate capital control index (ACI) which covers the eight other asset categories in the Fernández et al. (2015) dataset for both capital inflows and capital outflows excluding money market flows and direct investment. I also include capital controls on direct investment inflows in all regressions when they are present in a given country-year. It is important to be able to distinguish the effects of capital controls on direct investment inflows and capital controls on money market inflows.

Table 3 contains the results of the baseline fixed effects panel data regressions with country and year fixed effects. Cyprus, Malta, the Netherlands, Hong Kong, and Singapore are not included in the final sample due to extreme observations in direct investment or in the determinants. Kuwait, Ethiopia, Qatar, The United Arab Emirates, and Uzbekistan are not included due to data unavailability. The final sample includes 90 countries for the years 1995–2015. The results of the Hausman specification tests rejecting the null hypothesis of no systematic difference in random effects coefficients versus fixed effects coefficients are listed in the last row of Table 3. The joint significance of the year fixed effects is confirmed by an F-test, not presented here for brevity but available from the author. In the first column, the growth rate is significant and positive. The coefficient on the dummy variable for one money market capital control is statistically significant and positive, but this is not the case for the dummy variable for both money market capital controls. This means that country-years with one capital control on money market inflows in place have statistically significantly more direct investment inflows than country-years with no capital controls, but this result does not hold for country-years with both capital controls on money market inflows in place. Finally, the interactions of the two capital control dummies with the growth rate are both statistically significant and negative. The interaction between the per capita growth rate and money market capital controls indicates that high-growth (low-growth) countries which impose strong money market capital controls will receive less (more) direct investment inflows, all else equal. Interpreted jointly, the evidence indicates that the effects of money market capital control policy on direct investment inflows are larger in slower-growing countries than in faster-growing countries. A country in the first quartile of growth rates at 0.59% and that imposes one restriction on money market inflows expects \(.851-.190\times 0.59=.739\) percentage points higher direct investment. Likewise, a country in the third quartile of growth rates at 4.32% and that imposes one restriction on money market capital inflows expects \(.851-.190\times 4.32=.03\) percentage points higher direct investment. As the direct investment sample mean is 3.41% of GDP, this means that a typical slower-growing country that imposes capital controls on money market inflows expects approximately 21.7% higher direct investment, while a typical faster-growing country expects approximately .88% higher direct investment.

I have shown that the results in column (1) of Table 3 suggest that countries that use either one of the restrictions on money market inflows receive higher direct investment inflows. This is not the case for column (2) which contains the estimates including the aggregate capital control index. A higher value for the aggregate capital control index represents a broader use of capital controls for a particular country in a given year. The statistical insignificance of the aggregate control index suggests that on average, capital controls broadly do not influence the volume of direct investment inflows, all else equal. This result is consistent with the previous findings of the literature on capital controls (see, e.g., Montiel and Reinhart 1999; Carlson and Hernandez 2002; Alfaro et al. 2005). I do find a statistically significant and negative coefficient on the interaction term implying that faster-growing (slower-growing) countries that impose money market capital controls broadly receive less (more) direct investment.

The principal outcome from the results reported in Table 3 is the statistically significant and positive coefficient on the money market inflows capital control variable. Previous studies have predicted significantly higher FDI as a share of total flows, but insignificantly predicted higher levels of FDI (see, e.g., Montiel and Reinhart 1999 and Carlson and Hernandez 2002) This is the first study to show that a capital control on short-term inflows can lead to a higher level of direct investment. The theoretical framework introduced in earlier and extended in “Appendix 1” further informs the interpretation of the positive coefficient on the money market capital control variable. Recall that for the relatively elastic case, a capital control on short-term debt implies an increase in direct investment flows. This follows from the fact that an elasticity greater than 1 reflects increasing marginal returns with respect to the level of direct investment. Finally, the relationship between the growth rate and money market inflows capital controls also gives insight about the underlying mechanism. As discussed above, the joint relationship translates in .739 percentage points higher direct investment for low-growth countries that use money market inflows capital controls, and .03 percentage points higher direct investment for high-growth countries that use money market inflows controls. However, exclusive of the capital control, lower-growth countries attract less direct investment, not more (given the statistically significant and positive coefficient on the growth rate). These conditions support the interpretation that investors perceive capital controls on money market inflows in lower-growth countries serve as a signal of stability.

Finally, reverse causality may be the cause of the positive coefficient on the money market inflows capital control dummy in addition to the positive (yet insignificant) coefficient on the direct investment capital control dummy. If policymakers impose capital controls in response to higher capital inflows or if the countries that impose capital controls are the countries with higher inflows, reverse causality may pose a serious challenge. In the next section, I apply instrumental variables panel data random effects regression to address the potential reverse causality and confirm the results hold. When I address the endogeneity of capital controls, I also show that the coefficient on the direct investment capital control dummy becomes statistically significant and negative. In the section on sensitivity analysis, I present the results of Arellano–Bond generalized method of moments estimation.

Instrumental Variables

As discussed above, reverse causality is a challenge for regression analysis of capital flows (e.g., direct investment) on policy variables like capital controls.Footnote 11 Extra care must be taken to capture exogenous variation in the capital control that is unaffiliated with direct investment to capture the effect that capital controls have on the level of direct investment inflows. The same potentially reverse causality is true for other determinants of direct investment, particularly institutional quality and the level of imports. It is expected that countries with better institutions attract more direct investment. Conversely, the level of direct investment can help a country improve its institutions (Alfaro et al. 2005). Imports also exist in the potentially reverse direction of causality due to import-substituting direct investment. The potential for reverse causality in Eq. (1) is addressed with instrumental variables random effects regression, instrumenting for legal/property rights, imports, and the three capital controls variables.

Instrumental variables panel data random effects regression obtains coefficient estimates for the endogenous determinants using variables (instruments) that naturally exhibit exogenous variation. Following Alfaro et al. (2005) and Porta et al. (1998), I use legal origins as instruments for institutional quality (legal/property rights). Porta et al. (1998) study the legal origins of contemporary nation-states as principle determinants in shaping a country’s current financial institutions, the associated legislation on investor protection, the enforcement of such legislation, and the extent of concentration of firm ownership across countries. The authors show that most countries’ institutions can be traced back to one of four European legal systems: English common law, French civil law, German civil law, and Scandinavian civil law. Alfaro et al. (2005) adopt these four legal-origin variables as exogenous determinants of institutional quality and find that French legal origin and British legal origin are significantly predictive. I use French and British legal origins as two instrumental variables for legal/property rights.

Central bank independence has been cited consistently in the literature on the determinants of capital controls (see, e.g., Johnston and Tamirisa 1999; Grilli and Milesi-Ferretti 1995). Central banks which are legally but also operationally more independent are less likely to impose capital controls. Data on central bank independence are obtained from Garriga (2016), a database on central bank independence that covers 172 countries between 1970 and 2012. The measure of central bank independence is a statutory continuous index that reflects the level of independence on dimensions of personnel, finance, and policy. I use central bank independence as an instrument for the capital control on direct investment inflows. Operational monetary aspects of an economy are not attributes that reflect direct investment decisions on the margin. From a longer-term perspective, e.g., an examination of FDI stocks in cross section, this may be important for FDI through stable growth. Central bank independence in this case is important for FDI inflows, only marginally, through fewer capital controls.

The next instrument is a binary instrument that captures short-term interest rate hikes or drops. As a conservative measure, I use quarterly data on changes in the deposit rate from the IMF’s International Financial Statistics. To capture large short-term increases or decreases in the deposit rate, I obtain the annual average of the absolute value of the quarterly changes in the deposit rate. Interest rate hikes are a binary instrument which is equal to 1 in years when the annual average is greater than the median annual average. I use interest rate hikes as an instrument for money market capital controls. Large hikes or drops in the interest rate over short periods generate the incentives for large capital inflows or outflows in the form of short-term debt or portfolio flows. Direct investment is a more restrictive form of external capital, less associated with the forces triggering “hot money” like short-term debt and portfolio flows. Additionally, the interest rate that is relevant for the direct investor is the interest rate in their home country because that interest rate is the best measure of the opportunity cost of the capital invested.

The next two instruments come from the World Bank’s Database on Political Institutions (Cruz et al. 2016b). Following Giordani et al. (2017), Ghosh et al. (2014), Grilli and Milesi-Ferretti (1995), I use an indicator for right-leaning governments and an indicator for the electoral cycle. The indicator for right-leaning governments serves as an instrument for money market inflows capital control dummies. The political leaning of the governing party is used because right-leaning administrations tend to be less likely to use capital controls. The right-leaning government instrument takes on a within-year GDP-weighted share of all countries with right-leaning administrations. Finally, I use the electoral cycle of a country as an instrument for imports. Government expenditures and disposable incomes are well documented to increase with the electoral cycle, and the same can be reasonably expected of imports. The electoral cycle takes on a within-year GDP-weighted share of all countries with legislative or presidential elections in the following year.

The first-stage statistics are provided in Table 4. The first-stage F-statistic demonstrates that the legal-origins variables, the electoral cycle, and central bank independence are not weak instruments. However, the right-leaning government and interest rate hikes instruments have the typical weak instrument challenges.

Table 5 contains the results from the two-stage least squares instrumental variables random effects estimation. The random effects estimator is the default in this case due to the time-invariant legal-origins instrumental variables. There are two striking results: the coefficient on both money market capital controls is large at about 2 percentage points, positive, and statistically significant. Additionally, the coefficient on the direct investment inflows capital control is large at about 4 percentage points, negative, and statistically significant. This contrasts the result on the direct investment capital control in the baseline regression, suggesting that reverse causality was a challenge and that it is mitigated using instrumental variables.

The signs and magnitudes remain largely consistent with all previous results. The coefficient on the level of institutional quality is no longer significant. The magnitudes on the coefficient on the dummy that tracks countries with at least one restriction on money market inflows are small and insignificant. The results of this regression however are consistent with Cordella (2003), where a capital control tax has to be high enough to generate the outcome that increases capital inflows. This result complements the results in Table 5, where capital controls must be on both money market inflows transactions to increase direct investment inflows.

The instrumental variables regression is over-identified, so a Sargan-Hansen overidentification test is possible. The \(\chi ^{2}\) statistic of 2.48 means that the null hypothesis that the overidentifying restrictions are valid is not rejected. Finally, a Hausman test confirms instrumental variables random effects are the consistent estimator for this model as compared to the usual panel data random effects estimator. The instrumental variables panel data random effects regression addressed the endogeneity of the capital control variables, provided consistent coefficient estimates, and confirmed that countries that use capital controls on money market inflows have higher direct investment.

Sensitivity Analysis

In this section, I perform sensitivity analysis in three ways. First, I implement alternative estimation methodologies to further test the sensitivity of reverse causality. Second, I re-estimate the instrumental variables specification with alternative determinants of direct investment that are emphasized in the FDI determinants literature. Finally, I comment on the relationship between capital controls and short-term debt.

Dynamic Panel

In the previous section, I addressed reverse causality between the dependent variable direct investment inflows and the capital control variables using instrumental variables panel data random effects regression. Reverse causality of imports and the level of institutional quality were also addressed. In this section, I address reverse causality by regressing the dependent variable on the baseline specification lagged one year and by implementing Arellano–Bond generalized method of moments.

Assume that the capital control variables are predetermined in the model if the variables are independent of all subsequent structural disturbances \(\varepsilon _{t+s}\) for \(s \ge 0\). In this case, lagging the right-hand side of Eq. (1) is sufficient for controlling for the reverse causality. If however serial correlation is present, the assumption that the variables are predetermined will be violated. Arellano–Bond generalized method of moments is useful in this case, because it uses lags and lags of differenced terms as instruments for the Arellano–Bond specification. I show that serial correlation is mitigated using the Arellano–Bond procedure.

Table 6 presents the results of fixed effects panel regressions with the right-hand side of Eq. (1) lagged one year in column (1) and Arellano–Bond generalized method of moments (GMM) regression in column (2). The lagged regression estimates the effect of last year’s money market capital control policy on this year’s direct investment inflows. The results are largely consistent with the baseline regression. Importantly, the coefficient on one money market capital control lagged one year is still statistically significant and positive. However, in this regression, the coefficient on the direct investment inflows capital control lagged one year is statistically insignificant from zero. Together, these results indicate that the lagged regression is not sufficient to overcome the problem of reverse causality. The lagged number of telephone lines becomes statistically significant and positive in the lagged regression. The lagged value of infrastructure suggests that improved infrastructure leads to higher FDI with a lag.

The second column of Table 6 contains the results of the Arellano–Bond GMM estimates. FDI inflows remain the dependent variable, and lagged FDI inflows enter Eq. 1 as a right-hand side endogenous explanatory variable. Imports and property rights are assumed to be endogenous as well. The growth rate and the interaction of the growth rate with the capital control variables are assumed predetermined, and the remaining variables enter the equation lagged (except for distantness, permitted to enter contemporaneously). Level lags of the endogenous and predetermined variables are used as instruments. The remaining right-hand side variables serve as instruments as lagged differences.

The results obtained using the Arellano–Bond generalized method of moments mirror those obtained through the lagged regression. The coefficient on the money market inflows capital control remains positive and statistically significant, and the coefficient on the interaction with the growth rate is negative and statistically significant. (Lagged interaction is insignificant with the GMM estimation.) Thus, countries which use a capital control on money market inflows have a higher level of direct investment, and this effect is decreasing in the growth rate. The endogeneity of the capital controls has been addressed in three ways, and this result has been confirmed in each of the three ways.

The coefficient on the direct investment inflows capital control however remains statistically insignificant from zero. This may signal that the Arellano–Bond GMM estimation does not in this case sufficiently account for the reverse causality. The Arellano–Bond test for autocorrelation confirms that autocorrelation in the first-differenced errors is not a concern with a test statistic of − 16.52 for the first order and 0.687 for the second order. This implies the second order is not rejected, as expected. However, the overidentification test does reject the Arellano–Bond GMM instruments as not valid. This outcome could be expected given our expectation that reverse causality has not been sufficiently mitigated.

Additional Robustness

The literature on the determinants of direct investment describes many attributes that are important for direct investment inflows. It is possible that other determinants of direct investment could be important for the relationship between direct investment inflows and capital controls. For information on additional determinants, I draw on the sources that jointly inform the selection of the determinants for the baseline specification: Eicher et al. (2012), Alfaro et al. (2008), Blonigen (2005). Other determinants that are commonly cited include control of corruption, the tariff rate, the level of financial development, and macroeconomic volatility.

Control of corruption captures the extent to which public power is exercised for private gain. Control of corruption is an index obtained from the World Governance Indicators database. Higher values of the control of corruption index represent better outcomes, implying lower costs and higher returns for direct investors. Given that direct investment and international trade are highly integrated, the tariff rate represents an implicit FDI friction. Stock market capitalization captures the level of financial development (Beck et al. 2000, 2009). Improved access to financing as a result of financial development improves long-run economic growth and therefore encourages investment (Benhabib and Spiegel 2000; Claessens and Laeven 2003; Levine and Zervos 1996; Levine 2001). Finally, macroeconomic volatility is measured as the standard deviation of the GDP growth rate for a given country over the sample period. The relationship between capital controls and direct investment may be influenced by macroeconomic volatility. There exists asymmetry in volatility outcomes, affecting investment differently in the source country than in the host country, contributing to ambiguity in the predicted effects on FDIFootnote 12 (Chenaf-Nicet and Rougier 2016).

Table 7 contains the results of the first-stage statistics for the four alternative instrumental variables regressions. The first pair of columns displays the first-stage statistics for the instrumental variables specification with control of corruption in the place of legal/property rights. The following three pairs of columns provide the first-stage statistics with the tariff rate, macroeconomic volatility, and financial development included among the exogenous covariates. The results in Table 7 are categorically consistent with the first-stage statistics presented in Table 4. The right-leaning government indicator and the indicator for interest rate hikes are weak instruments. The partial-\(R^{2}\) of central bank independence and electoral cycle are improved in the regressions that control for the tariff rate and the level of financial development, but are also not so high such that they suffer from the “strong instrument” problem.

Table 8 contains the results of the instrumental variables panel data random effects regression using the alternative determinants of direct investment. The random effects estimator is used in this case because the legal-origins instruments in addition to the measure for macroeconomic volatility are time-invariant. None of the alternative covariates across (1) through (4) in Table 8 are statistically significant. Meanwhile, the results in columns (1) and (2) are largely consistent with the instrumental variables results in Table 5.

Columns (3) and (4) are different, while consistent in sign, the coefficients on the capital control variables are no longer statistically significant. This suggests that the influence that a money market capital control has on direct investment may share components with the level of financial development or with macroeconomic volatility. Variation in financial development or volatility might partially explain the relationship between capital controls and direct investment that we have observed. This is consistent with the notion that countries with sophisticated capital markets are less likely to benefit from using capital controls. Nevertheless, these variables are not statistically significant and thus do not contain predictive power.

Short-Term Debt Regression Estimation

The level of foreign direct investment inflows is not the purpose of imposing money market inflows capital controls; the purpose of these controls is more likely related to money market inflows. Evidence that money market inflows decrease with money market inflows capital controls is therefore highly relevant to the central research question. Analysis using country-level debt flows is more challenging than with investment flows. Alfaro et al. (2005) discuss the challenges in estimating the economic consequences of debt flows, highlighting measurement discrepancies in the debt flows data. Debt flows are also generally influenced by decisions that are distinct from equity flows. Finally, the sample is much smaller with only 55 countries reporting.

I re-estimate Eq. 1 using external short-term debt flows as a percent of GDP for the dependent variable. The quantity of money market capital controls imposed in a typical economy in addition to the other determinants in the baseline regression remain. The regression in Table 9 is estimated using panel data random effects regression. The explanatory variables are as expected in sign and significance, except for the capital control variables which are positive and not significant. This is consistent with the majority of the literature which finds that capital controls do not influence volume of capital flows (see, e.g., Montiel and Reinhart 1999; Carlson and Hernandez 2002; Alfaro et al. 2005; Forbes et al. 2015). The results require some judgment in their interpretation. The influence from equity flow decisions will impose multicollinearity in this specification, causing the coefficient to be biased toward zero. Additionally, Alfaro et al. (2005) point out that measurement error in debt flows data versus changes in the debt stocks data will also cause the coefficients to be biased toward zero. The smaller sample of countries for which data on debt flows are available however is countries which are more likely to use capital controls. These countries tend to be smaller, have lower incomes, but are growing faster.Footnote 13 As such, the coefficient on money market capital control faces opposing forces.

Conclusion

The use of money market inflows capital controls is common, and still the costs of using this kind of policy are not fully understood. I have shown that using money market capital controls do not cost a country its direct investment. In fact, slower-growing countries that use capital controls on money market inflows expect higher direct investment inflows. This result is consistent with the interpretation that investors perceive this capital control as a signal of stability. The contribution of this result is novel for two reasons: (1) the focus on the response of FDI to a granular level of variation in capital controls and (2) the finding that the volume of FDI is increasing with the use of this control. I have put this to result through multiple scenarios of reverse causality including instrumental variables and Arellano–Bond GMM and confirmed that countries that use money market inflows capital controls receive a higher level of direct investment. Future research should tie down the structural relationship among capital controls, the growth rate, and direct investment. Future research should also look into whether other cash flows management policies or other monetary or fiscal policies that mitigate economic volatility demonstrate the same signal effect. Finally, future work should determine whether this signal can be observed at the firm level and study the experience of firms under such conditions.

Notes

Information derived from the IMF’s AREAER report (Fernández et al. 2015).

Schindler (2009) covers restrictions for 91 countries from 1995 to 2005 on inflows and outflows over 6 asset categories.

The remaining 8 asset categories are bonds and other debt with maturity of more than one year, equity, collective investment, financial credit, derivatives, guarantees and sureties, and real estate.

The average is the cumulative percent of the cumulative GDP for each group of countries.

See Kinda (2012) for a detailed investigation on the role infrastructure plays as a driver of FDI flows.

I confirm that reverse causality is a mitigating factor in the relationship between foreign direct investment and capital controls on money market inflows. Results using probit and multinomial logit are available in “Appendix 1”.

Additionally, the definition of macroeconomic volatility is distinct from macroeconomic uncertainty. Macroeconomic volatility measures the variability of an economic series by taking into account all of the transitory variations of a statistical series. See Cariolle (2012) for an evaluation of the commonly used for calculating macroeconomic volatility. Macroeconomic uncertainty more specifically intends to measure the unpredictability of variations in total variability (Aizenman and Pinto 2004). In any case the evidence tends to complement the theory suggesting reduced investment under uncertainty (Dixit and Pindyck 1994).

For the sample of 55 countries which have data available on short-term debt, mean GDP is $298 billion USD, mean per capita GDP is $4,142 USD, and the mean GDP growth rate is 2.78%.

References

Aizenman, J. and B. Pinto. 2004. Managing volatility and crises: A practitioner’s guide overview. Working Paper 10602, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Alfaro, L., A. Chari, and F. Kanczuk. 2017. The real effects of capital controls: Firm-level evidence from a policy experiment. Journal of International Economics 108(C): 191–210.

Alfaro, L., S. Kalemli-Ozcan, and V. Volosovych. 2005. Capital flows in a globalized world: The role of policies and institutions. Working Paper 11696, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Alfaro, L., S. Kalemli-Ozcan, and V. Volosovych. 2008. Why doesn’t capital flow from rich to poor countries? An empirical investigation. The Review of Economics and Statistics 90(2): 347–368.

Arora, V., K. Habermeier, J. Ostry, and R. Weeks-Brown. 2013. The liberalization and management of capital flows: An institutional view. Revista de Economia Institucional 15(28): 205–256.

Asiedu, E., and D. Lien. 2004. Capital controls and foreign direct investment. World Development 32(3): 479–490.

Beck, T., A. Demirgüç-Kunt, and R. Levine. 2000. A new database on the structure and development of the financial sector. The World Bank Economic Review 14(3): 597–605.

Beck, T., A. Demirgüç-Kunt, and R. Levine. 2009. Financial institutions and markets across countries and over time—data and analysis. Policy Research Working Paper Series 4943, The World Bank.

Benhabib, J., and M.M. Spiegel. 2000. The role of financial development in growth and investment. Journal of Economic Growth 5(6): 341–360.

Benmelech, E., and E. Dvir. 2013. Does short-term debt increase vulnerability to crisis? Evidence from the East Asian financial crisis. Journal of International Economics 89(2): 485–494.

Bergstrand, J.H., and P. Egger. 2007. A knowledge-and-physical-capital model of international trade flows, foreign direct investment, and multinational enterprises. Journal of International Economics 73(2): 278–308.

Blonigen, B.A. 2005. A review of the empirical literature on fdi determinants. Atlantic Economic Journal 33(4): 383–403.

Cardarelli, R., S. Elekdag, and M.A. Kose. 2010. Capital inflows: Macroeconomic implications and policy responses. Economic Systems 34(4): 333–356.

Cariolle, J. 2012. Measuring macroeconomic volatility- applications to export revenue data, 1970–2005. Working Papers I14, FERDI.

Carlson, M. and L. Hernandez. 2002. Determinants and repercussions of the composition of capital inflows. International Finance Discussion Papers 717, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.).

Chenaf-Nicet, D., and E. Rougier. 2016. The effect of macroeconomic instability on fdi flows: A gravity estimation of the impact of regional integration in the case of euro-mediterranean agreements. International Economics 145: 66–91. International trade, FDI and growth: some interactions.

Claessens, S., and L. Laeven. 2003. Financial development, property rights, and growth. The Journal of Finance 58(6): 2401–2436.

Cordella, T. 2003. Can short-term capital controls promote capital inflows? Journal of International Money and Finance 22(5): 737–745.

Cruz, C., P. Keefer, and C. Scartascini. 2016a. Database of Political Institutions Codebook, 2015 Update (DPI2015). Updated version of thorsten beck, george clarke, alberto groff, philip keefer, and patrick walsh, 2001. “New tools in comparative political economy: The database of political institutions,” 15:1, 165–176 (september) world bank economic review, Inter-American Development Bank.

Cruz, C., P. Keefer, and C. Scartascini. 2016b. Database of political institutions codebook, 2015 update (dpi2015). Updated Version of Thorsten Beck, George Clarke, Alberto Groff, Philip Keefer, and Patrick Walsh, 2001. “New tools in comparable political economy: The Database of Political Institutions.” 15:1, Inter-American Development Bank.

Dell’Ariccia, G., J. di Giovanni, A. Faria, A. Kose, P. Mauro, J.D. Ostry, M. Schindler, and M. Terrones. 2007. Reaping the benefits of financial globalization. Technical report, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

Dell’Erba, S., and D. Reinhardt. 2015. FDI, debt and capital controls. Journal of International Money and Finance 58: 29–50.

Dixit, A.K., and R.S. Pindyck. 1994. Investment under uncertainty. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Edison, H., and C.M. Reinhart. 2001. Stopping hot money. Journal of Development Economics 66(2): 533–553.

Edwards, S. 1999. How effective are capital controls? The Journal of Economic Perspectives 13(4): 65–84.

Edwards, S., and R. Rigobon. 2009. Capital controls on inflows, exchange rate volatility and external vulnerability. Journal of International Economics 78(2): 256–267.

Eichengreen, B., and A. Rose. 2014. Capital controls in the 21st century. Journal of International Money and Finance 48: 1–16.

Eicher, T., L. Helfman, and A. Lenkoski. 2012. Robust FDI determinants: Bayesian model averaging in the presence of selection bias. Journal of Macroeconomics 34(3): 637–651.

Fernández, A., M.W. Klein, A. Rebucci, M. Schindler, and M. Uribe. 2015. Capital control measures: A new dataset. Working Paper 20970, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Forbes, K., M. Fratzscher, T. Kostka, and R. Straub. 2016. Bubble thy neighbour: Portfolio effects and externalities from capital controls. Journal of International Economics 99: 85–104.

Forbes, K., M. Fratzscher, and R. Straub. 2015. Capital-flow management measures: What are they good for? Journal of International Economics 96(S1): 76–97.

Forbes, K.J. 2005a. Capital controls: Mud in the wheels of market efficiency. Cato Journal 25(1): 153–166.

Forbes, K.J. 2005b. The microeconomic evidence on capital controls: No free lunch. NBER Working Papers 11372, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Garriga, A.C. 2016. Central bank independence in the world: A new data set. International Interactions 42(5): 849–868.

Ghosh, A.R., J.I. Kim, and M.S.Q.J. Zalduendo. 2012. Surges. Technical report, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

Ghosh, A.R. and M.S. Qureshi. 2016. What’s in a name? That which we call capital controls. Technical report, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

Ghosh, A.R., M.S. Qureshi, and N. Sugawara. 2014. Regulating capital flows at both ends; Does it work? IMF Working Papers 14/188, International Monetary Fund.

Giordani, P., M. Ruta, H. Weisfeld, and L. Zhu. 2017. Capital flow deflection. Journal of International Economics 105: 102–118.

Grilli, V., and G.M. Milesi-Ferretti. 1995. Economic effects and structural determinants of capital controls. Staff Papers (International Monetary Fund) 42(3): 517–551.

Gupta, P., D. Mishra, and R. Sahay. 2007. Behavior of output during currency crises. Journal of International Economics 72(2): 428–450.

Gurevich, T. and P. Herman. 2018. The dynamic gravity dataset: 1948–2016. USITC Working Paper 2018-02-A, United States International Trade Commission.

Gwartney, J., R. Lawson, and J. Hall. 2016. Economic freedom of the world: 2016 annual report. Technical report, Vancouver, B.C.

Habermeier, K.F., A. Kokenyne, and C. Baba. 2011. The effectiveness of capital controls and prudential policies in managing large inflows. Technical report, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

IMF Independent Evaluation Office. 2005. IEO evaluation report on the IMF’s approach to capital account liberalization 2005. International Monetary Fund.

International Monetary Fund. 2010. The fund’s role regarding cross-border capital flows. Technical report, Washington, DC.

International Monetary Fund. 2011a. Macroprudential policy: An organizing framework. Technical report, Washington, DC.

International Monetary Fund. 2011b. Recent experiences in managing capital inflows cross-cutting themes and possible guidelines. Technical report, Washington, DC.

International Monetary Fund. 2011c. The multilateral aspects of policies affecting capital flows. Technical report, Washington, DC.

International Monetary Fund. 2012. Liberalizing capital flows and managing outflows. Technical report, Washington, DC.

Johnston, B.R. and N. Tamirisa. 1999. Why do countries use capital controls? 98.

Kaplan, E., and D. Rodrik. 2002. Did the Malaysian capital controls work?, 393–440. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kinda, T. 2012. On the drivers of fdi and portfolio investment: A simultaneous equations approach. International Economic Journal 26(1): 1–22.

Kose, M.A., E. Prasad, K.S. Rogoff, and S.-J. Wei. 2006. Financial globalization: A reappraisal. Working Paper 12484, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Levine, R. 2001. International financial liberalization and economic growth. Review of International Economics 9(4): 688–702.

Levine, R., and S. Zervos. 1996. Stock market development and long-run growth. The World Bank Economic Review 10(2): 323–339.

Lucas, R.E. 1990. Why doesn’t capital flow from rich to poor countries? The American Economic Review 80(2): 92–96.

Magud, N.E., C.M. Reinhart, and K.S. Rogoff. 2011. Capital controls: Myth and reality—a portfolio balance approach. Working Paper 16805, National Bureau of Economic Research.

McKinnon, R. 1999. The East Asian dollar standard, life after death? Working Papers, Stanford University, Department of Economics.

Montiel, P., and C.M. Reinhart. 1999. Do capital controls and macroeconomic policies influence the volume and composition of capital flows? Evidence from the 1990s. Journal of International Money and Finance 18(4): 619–635.

Ocampo, J.A., and J.E. Stiglitz. 2008. Capital market liberalization and development. Initiative for policy dialogue series. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

OECD 1998. OECD benchmark definition of foreign direct investment, third edition (1996). Financial Market Trends (70).

Ostry, J., A. Ghosh, K.F. Habermeier, L. Laeven, M. Chamon, M. Qureshi, and A. Kokenyne. 2011. Managing capital inflows; What tools to use? IMF Staff Discussion Notes 11/06, International Monetary Fund.

Ostry, J.D., A.R. Ghosh, and A. Korinek. 2012. Multilateral aspects of managing the capital account. Technical report, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

Porta, R.L., F. LopezdeSilanes, A. Shleifer, and Robert W. vishny. 1998. Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy 106(6): 1113–1155.

Pyun, J.H., and J. An. 2016. Capital and credit market integration and real economic contagion during the global financial crisis. Journal of International Money and Finance 67: 172–193.

Qureshi, M.S., J.D. Ostry, A.R. Ghosh, and M. Chamon. 2011. Managing capital inflows: The role of capital controls and prudential policies. NBER Working Papers 17363, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Ramey, G., and V.A. Ramey. 1995. Cross-country evidence on the link between volatility and growth. American Economic Review 85(5): 1138–1151.

Reinhart, C. and V. Reinhart. 2009. Capital flow bonanzas: An encompassing view of the past and present. In NBER international seminar on macroeconomics 2008, pp. 9–62. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Reinhart, C. and T.R. Smith. 1998. Too much of a good thing: The macroeconomic effects of taxing capital inflows. MPRA Paper 13234, University Library of Munich Germany.

Rodrik, D. and A. Velasco. 1999. Short-term capital flows. Working Paper 7364, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Schindler, M. 2009. Measuring financial integration: A new data set. IMF Staff Papers 56(1): 222–238.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful for the helpful comments and discussions with Sangeeta Pratap. I am thankful for the helpful comments from Merih Uctum, Chun Wang, Thom Thurston, Justin Pierce, and an anonymous referee. I would also like to thank USITC seminar participants, especially Saad Ahmed, Alan Fox, Tamara Gurevich, Ross Hallren, Peter Herman, and Sandra Rivera, participants of the Symposium on International Trade Policy at the EEA Conference, especially Thomas Osang, and Diego Nocetti, and participants of the Midwest International Trade seminar.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Theoretical Framework

Magud et al. (2011) use the capital asset pricing model to explain the behavior of external capital flows. The first subsection entails the framework on short-term flows developed in Magud et al. (2011). In the second subsection, I extend the framework to shift the perspective to long-term flows and characterize the relationship between long-term flows and a capital control imposed on short-term flows.

There are two different categories (maturities) of external capital flows: short-term flows \(S_{t}\) and long-term flows \(L_{t}\), which together make up total capital flows \(F_{t}\). Short-term capital flows can be expressed as a share x of total capital flows: \(xF_{t}\). The interest rate for short-term capital flows is \(r^{*}\) and the interest rate for long-term flows, r. The variance for short-term capital flows is \(\sigma _{r^{*}}^{2}\), and the variance for long-term flows is \(\sigma _{r}^{2}\).

Short-Term Flows

In Magud et al. (2011), a representative investor maximizes expected utility of wealth given her risk preferences. This means that the representative investor will trade off risk (variance) \(\sigma _{w}^{2}\) for expected return \(\overline{w}\) on the portfolio of external capital flows. Expected return on total capital flows can be expressed as

The second term on the right-hand side represents the premium attributed to short-term capital flows. The variance of the return on total external capital flows is given by

A position in which \(x=1\) implies that all external capital flows are in short-term capital. This is all high risk, high return. The contradistinction \(x=0\) implies that all external capital flows are in long-term capital which is lower risk, and lower return. We solve for the optimal share in short-term capital flows x, by using a log-linearized approximation of expected utility;

The first-order condition implies:

where \(\Phi\) is the coefficient of relative risk aversion and \(\alpha\) is the share of short-term external capital flows that minimizes variance;

Suppose that we impose a capital control on short-term external capital flows. The capital control can be represented by a tax \(\tau\) which drives a wedge between the rents paid for short-term capital by the domestic borrower and the return received by the international lender. We can redefine \(r^{*}\) as the after-capital-controls return on short-term external capital flows:

As Eq. 7 indicates, a capital control in the form of a positive tax will decrease the return on short-term capital flows. All else equal, this kind of capital control policy implies that short-term capital flows are relatively less rewarding. Formally:

thus, a decrease in the return on short-term capital flows \(r^{*}\) implies a decrease in the optimal share of short-term capital flows x.

Aggregation over investors j with wealth \(W_{j}\) implies demand for short-term flows \(\sum _{j}x_{j}W_{j}\) and total wealth \(\overline{W}=\sum _{j}W_{j}\). In equilibrium, total supply of short-term flows \(V^{*}\) should equal total demand for short-term flows:

We can characterize the aggregation by multiplying through Eq. 5 by \(W_{j}\). This yields, with some manipulation:

where \(\Phi =\sum _{j}\frac{\Phi _{j}}{W_{j}/\overline{W}}\) is redefined to represent aggregate risk aversion.

In aggregate, the share of short-term capital flows falls with the use of a capital control:

We can also show that aggregate capital flows increase with the use of a capital control:

Magud et al. (2011) totally differentiate Eq. 10 with respect to \(V^{*}\) and \(\overline{W}\) to further investigate the way the levels of capital flows change with the use of capital controls:

Equation 13 is expression that describes how changes in short-term capital flows and total capital flows contribute to changes in the short-term interest rate. The authors elaborate on this relationship with the objective of identifying the elasticity of short-term flows with respect to total flows, \(\eta =\frac{{\mathrm{{d}}}V^{*}}{{\mathrm{{d}}}\overline{W}}\frac{\overline{W}}{V^{*}}\). With some manipulation:

Equation 14 is an expression for the way changes in the supply of short-term capital flows influence marginal returns on short-term capital flows, as a function of the elasticity of short-term capital flows with respect to total capital flows. Intuitively, this is expected: elasticity reflects the rate at which marginal returns are changing, where \(\eta >1\), marginal returns are increasing in the level of short-term capital flows. A decrease in the return on capital flows due to a capital control \(\tau\) is therefore met by a decrease in the level of short-term capital flows. If \(\eta = 1\), marginal returns are constant and capital flows do not change in response to a capital control. When \(0<\eta <1\), marginal returns are decreasing in the level of short-term capital flows. In this case, optimal capital flow behavior is to expand given an additional decrease in the return on short-term capital flows, i.e., from a capital control tax \(\tau\). The intuition here is that investors now require a larger quantity of capital invested to earn the same return. The key point is that for the desired outcome of capital control policy to work, the elasticity between short-term flows and total flows should be greater than 1.

Long-Term Flows

We are interested in the way that a capital control on short-term flows influences long-term flows with respect to total flows. I extend the framework of Magud et al. (2011) to characterize this relationship. Following Eq. 5 in Appendix, the share of long-term flows in total flows is given by:

The share of long-term flows as written in Expression (16) depends on the optimal share of short-term flows. Aggregation over investors j with wealth \(W_{j}\) gives the demand for long-term flows \(\sum _{j}(1-x_{j})W_{j}\). In equilibrium, the total supply of long-term flows \(Q^{*}\) should equal the total demand for long-term flows:

We can characterize the aggregation by multiplying through Eq. 16 by \(W_{j}\). This yields with some manipulation:

We can totally differentiate to discern how the return on short-term flows changes with changes in long-term flows and with changes in total flows:

With the objective of identifying the elasticity of long-term flows with respect to total flows \(\xi =\frac{{\mathrm{{d}}}Q^{*}}{{\mathrm{{d}}}\bar{W}}\frac{\bar{W}}{Q^{*}}\), we can characterize the marginal returns following Equation 19:

Equations 20 and 21 are conditions which characterize the response of long-term capital flows and total capital flows to a change in the after-tax return on short-term capital flows and depend on the value of the exogenous parameter, elasticity \(\xi\).

When the elasticity \(\xi >1\), marginal returns of long-term flows with respect to total flows are increasing and imply vis-a-vis Eqs. 20 and 21 that the marginal returns of short-term flows are decreasing. In this case, a capital control on short-term flows \(\tau\) (implying a decrease in \(r^{*}\)) leads to an expansion of long-term and total capital flows. When \(\xi <1\), marginal returns of long-term flows are decreasing and Eqs. 20 and 21 are positive. In this case, the capital control implies an decrease in the level of long-term and total flows.

Appendix 2: Variables

See Table 10.

Appendix 3: Other Data Visualization

The positive frequencies in Fig. 4 for the three different shades of blue represent the three distinct ways one country can add restrictions on short-term capital inflows in a given year, and the negative frequencies in three shades of purple represent the three distinct ways one country can remove restrictions on short-term capital inflows in a given year. Thus, blues represent country-year capital control additions, and purples represent country-year capital control removals.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nugent, R.J. Restrictions on Short-Term Capital Inflows and the Response of Direct Investment. Eastern Econ J 45, 350–383 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41302-018-0122-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41302-018-0122-9