Abstract

This paper develops and discusses a model describing how multinational enterprises from emerging economies (EMNEs) overcome the liability of outsidership in their internationalization from a capability-building perspective. Our aim is to celebrate the important intellectual contribution of Johanson and Vahlne (J Int Bus Stud 40(9):1411–1431, 2009), who introduced the liability of outsidership concept. We first discuss learning from the local environment that can reduce outsidership, and then explain how greater absorptive capacity can translate into better performance internationally. Finally, we elaborate on how the institutional environment further conditions the process and the outcomes of learning. We conclude with some suggestions for future research from five theoretical perspectives: learning, social network theory, institutional theory, resource dependence theory, and MNE structure and design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Johanson and Vahlne’s “The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership”, published in JIBS in December 2009 has been one of the most influential papers published in international business (IB), reaching an impressive citation count and affecting a broad set of topical research streams over the years. Even though the original 1977 model has become a key reference in IB research, Johanson and Vahlne (henceforth, J&V) have kept their theory alive by offering a number of revisions to the original model, addressing advances in – and the changing landscape of – IB research and practice (Coviello, Kano, & Liesch, 2017; Hutzschenreuter & Matt, 2017; Li, 2011; Santangelo & Meyer, 2017).

What J&V discuss in both the 1977 and 2009 articles concerns the conditions in which firms successfully enter and expand in foreign markets. The original 1977 model was published at the end of an era when multinationals were becoming bigger by internalizing international activities and functions, and at the dawn of one in which multinationals started restructuring to become configured as networks (both internally and externally).

The original model considered the firm on a stand-alone basis, used the behavioral approach to the firm’s decision-making process, and took the concept of psychic distance between home and host countries as a foundational concept (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977). In 2009, following a series of publications from Uppsala scholars, J&V proposed a revised model in which business network structures and embeddedness became core concepts. Their main argument was that markets are networks of relationships and firms are interacting with other actors in various complex and sometimes invisible network patterns (Johanson & Vahlne, 2009). Insidership in relevant business networks was considered a necessary condition for successful internationalization, and minimizing the liability of outsidership (LoO).

For J&V, the liability of foreignness became less important than the liability of outsidership and the host-country context (and psychic distance) became less important than the business network structure. In building that model, J&V clearly used theories, concepts, cases, and facts related to and derived from both the restructuring of Western multinationals and the emergence of Asian ones, especially Japanese ones. Therefore, the 2009 model was predominantly fit to describe, explain, and predict the internationalization processes of such firms. In this paper, we will analyze to what extent the rise of emerging economies and their multinationals may help advance scholarly discussion of the model, especially implications of the LoO for emerging economy multinational enterprises (EMNEs) and how to overcome it. As we will explain, firms from emerging economies face specific barriers in their attempts to internationalize. So what are the specifics of LoO in the case of EMNEs and how do they overcome it? How can EMNEs develop absorptive capacity to overcome the LoO? Answering those questions will be the focus of this paper, which largely adopts a capability-building perspective. However, learning theory, social network theory, institutional theory, resource dependence theory, and work on firm structure may all offer additional suggestions for future research.

OVERVIEW OF THE 2009 ARTICLE

A Comparison of the Updated Uppsala Model with the Original Model

Johanson and Vahlne (2009) argue that the challenges of entering a foreign market are similar to those of entering any other market: the entrant is unaware of both who the key actors in this market are and how the networking relationships operate. Both the 1977 and the 2009 models focus on the interplay between state variables and change variables. Their main changes adopted in 2009 are the following:

Replacing general market knowledge by relationship-specific knowledge;

Focusing on opportunity development beyond risk management;

Prioritizing the strengthening of network position over improving market position;

Emphasizing the importance of trust rather than economic behavior;

Highlighting learning and trust-building as the main outcomes arising from business activities.

The 2009 article introduced the LoO concept. J&V argue that the following, simple but fundamental assumption underlies their new model: the handicap a firm will face from a weak network position, when entering a foreign market, is more relevant than the conventionally acknowledged liability of foreignness (LoF). LoF refers more to the knowledge and repertoire needed to address a host country’s general market conditions. J&V proposed that insider status is necessary for successful internationalization, thereby reflecting a LoO for MNEs entering a foreign market.

It is surprising that the LoF and LoO concepts are mentioned in only a minority of the papers published on EMNEs that cite J&V 2009: from the 176 papers identified in Scopus, LoO is absent in 126 articles (71.6%), whereas LoF is missing from 93 articles (52.8%). Among those who do cite LoO, Tian and his colleagues have interpreted this concept as including “lack of bridging and bonding social capital” (Tian, Nicholson, Eklinder-Frick, & Johanson, 2018). Others have emphasized “trust-based relationships” (Fiedler, Fath, & Whittaker, 2017), “position in the foreign network” (Si & Liefner, 2014), “access to knowledge confined to network insiders” (Holtbrügge & Berning, 2018), or even “difficulties of initiating new relationships or maintaining existing ones” (Ferrucci, Gigliotti, & Runfola, 2018). In contrast, LoF is cited in the context of “limited access to resources and capabilities in the host market” (Fornes & Cardoza, 2019), “lack of knowledge about the new institutional environment” (Shen & Puig, 2018), “the costs of doing business abroad” (Curran & Ng, 2018), and “lack of legitimacy” (Zhang, Young, Tan, & Sun, 2018). Researchers typically do not clearly differentiate between foreignness and outsidership and sometimes use the terms interchangeably (e.g., Kingkaew & Dahms, 2019; Yu & Sharma, 2016).

The above notwithstanding, LoO is the key concept in J&V’s 2009 model. Forsgren, Holm, & Johanson (2015) explain that J&V’s network model was created to incorporate three developments in the IB literature. The first derived from studies showing that a firm’s competitive advantage cannot be completely explained by focusing solely on resources within the firm; relations with the environment play a significant role. The second development concerned acknowledging the increasing importance of collaboration: external relationships should be recognized as important to decision-making in internationalization, and in 2009, a firm’s knowledge base could no longer be seen as only a matter of internal knowledge. Knowledge residing in a network of business partners, customers, and suppliers would often be essential. Therefore, overcoming LoO resulting from absent or limited connections with local entities becomes the key in internationalization processes. This is where absorptive capacity comes in as a critical construct in explaining internationalization.

Forsgren, Holm, and Johanson (2015) regard multinational enterprises as engaged primarily in exchange activities, whereby each subsidiary is embedded in its own network of business relationships. The firm is best viewed as “federative” or “loosely coupled”, and control from corporate headquarters is more limited than is usually assumed. The concept of a foreign country being the source of economic, institutional, and cultural barriers, becomes less relevant. Instead, the challenge is to establish a position in a foreign business network, irrespective of whether this network covers a country, part of a country, or several countries. It is the network barriers that matter, rather than country barriers (though both may coincide in some cases).

To J&V, relationship development aiming at favorable network positioning is a process in which parties learn interactively and gradually to make commitments in building a relationship. It is largely an informal and socially constructed process, leading to a non-trivial level of mutual control. The authors illustrate such relationship development using the example of a Swedish firm whose internationalization to the USA was associated with building a business network that included its suppliers and customers. This relationship development involved seven firms, engaged in a ‘voluntarily orchestrated’ movement that lasted for 15 years.

In their 2009 model, J&V contemplated relationships among equals, with joint learning that would be associated with joint objectives. That is how firms would circumvent the liability of outsidership and succeed in their international expansions.

The Article’s Influence

We conducted a citation search and identified 1358 academic articles listed in Scopus that cite J&V 2009. An analysis of these citations shows that the model has served researchers in different ways, depending primarily on whether they focused on the internationalization of smaller or larger firms. The studies dealing with smaller firms mostly cited J&V for the importance of knowledge and networks in foreign operations (see, for example, De Clercq, Sapienza, Yavuz, & Zhou, 2012; Kontinen & Ojala, 2011; Mainela, Puhakka, & Servais, 2014). Those focused on larger firms connected J&V 2009 with a variety of topics, thereby attesting to the model’s versatility. For instance, it has been applied in studies about culture, national distance, and country differences (Ronen & Shenkar, 2013; Tung & Verbeke, 2010); in studies of foreign investment, acquisitions, and location choice (Lu, Liu, Wright, & Filatotchev, 2014; Sun, Peng, Ren, & Yan, 2012); in studies of networks, embeddedness, knowledge, and social capital (Herstad, Aslesen, & Ebersberger, 2014; Sun, Mellahi, & Thun, 2010); and in connection with other themes such as entrepreneurial management and subsidiaries’ roles (Pitelis & Teece, 2010; Rugman, Verbeke, & Yuan, 2011).

Among the papers listed in Scopus, we identified 201 documents that helped us understand how J&V 2009 has been discussed within the specific context of scholarship related to emerging economies. We were able to retrieve and review 178 of those documents, 176 of which we considered relevant to this analysis. We looked for documents whose keywords feature at least one of the following terms: emerging economies, emerging markets, EMNEs, Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, BRIC, or BRICS. Most of the 176 papers (namely 157, or 89%) reported the findings of empirical research, and the majority focused on large firms (110, or 63%). Although China was the emerging economy most often studied, J&V’s approach was also applied to EMNEs from India, Brazil, and Russia.1 In the next two sections, we will focus on those emerging economy firms, their distinctive features, and the importance of absorptive capacity for overcoming the LoO.

EMERGING ECONOMY FIRMS AND OUTSIDERSHIP

The internationalization of emerging market firms is a relatively recent phenomenon. EMNEs face conditions different from those encountered by firms that expanded internationally earlier. Their late-mover status has often led them to address differently the challenges posed by embeddedness and the LoO.

In the first wave of internationalization, North American and European firms expanded to both developed and less-developed countries. Direct investment gives better control of business activities abroad and often greater market power. Expansion to other developed economies required dealing with psychic distance and the liability of foreignness, but LoF was minimized in the case of Third World countries to which developed-country MNEs expanded. There they were fulfilling market needs, contributing to industrialization and seldom faced local competitors with an equivalent knowledge base. Legitimacy and recognition as valuable economic contributors came relatively easily.

The second wave of internationalization developed in a different context: the 1970s oil crisis, the emergence of new technologies (the so-called microelectronics revolution), and greater international competition. Japan, the main protagonist in the second wave, faced stronger LoF and LoO than had its predecessors. Japanese products were initially regarded as low quality, and Japanese firms were viewed with suspicion in the West due to their culture and work practices. Government support eventually allowed them to shake this stigma, a process described as economic catching-up (Amsden, 1989, 2009; Best, 1990). To penetrate the American market, Japanese firms adopted mechanisms such as creating new brands to disguise products’ actual origins. LoO was sometimes circumvented through partnerships, as in the case of Toyota partnering with General Motors to create a new firm (New United Motor Manufacturing Inc.) in California, in 1984.

The rise of EMNEs in the third wave of internationalization occurred in times of intense competition, institutional disarray, and increasingly stringent regulation (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2016; Rahaman, 2016). The initial movements of EMNEs into neighboring countries could be usefully described by the original 1977 model because the main determinant seemed to be psychic distance (even though many of these firms did not internationalize in a gradual way), but when emerging market firms began moving into more developed economies, outsidership became a serious obstacle (Li, Li, & Wang, 2019b).

If we look at EMNEs’ internationalization through the lens of J&V’s 2009 model, the state variable “positioning in business networks” was a complex challenge because the firms initially had only secondary positions in the key business networks. They were often lower-tier suppliers in global value chains led by developed-market multinationals (Awate, Larsen, & Mudambi, 2012; Luo & Tung, 2007). However, the other three variables of J&V’s model — identifying knowledge opportunities, relationship commitment decisions, and trust-building — can be mastered through developing absorptive capacity. That allowed EMNEs eventually to build favorable positions in the host country’s business networks.

BUILDING ABSORPTIVE CAPACITY IN OVERSEAS MARKETS

Absorptive capacity is “[the] ability to recognize the value of new information, assimilate it, and apply it to commercial ends” (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990: 128). It is the basis for acquiring and internalizing local knowledge. As one of the most widely applied theoretical constructs in organization studies, absorptive capacity also has substantial implications in internationalization research. J&V emphasized learning about local markets and network relationships in internationalization, a process where absorptive capacity plays an essential role. The process is critical to overcoming the liability of outsidership, so absorptive capacity strongly influences firms’ success in internationalization.

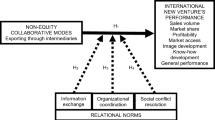

Of the 1358 papers citing J&V 2009 in Scopus, 329 (24%) also cited Cohen and Levinthal’s work on absorptive capacity (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). There is indeed an increasing volume of research at the intersection of absorptive capacity and the liability of outsidership, as Figure 1 shows.

Figure 2 represents a conceptual model that links the sources of learning and absorptive capacity with the process and outcome of internationalization. In our discussion below, we will apply it primarily in the context of firms from emerging economies.

Local Business Partners

MNEs must develop business relationships with local enterprises upon entering a host country. Through the exchange and cooperation with local suppliers and partners, firms accumulate both general knowledge about the local market (Barkema, Bell, & Pennings, 1996; Luo & Peng, 1999; Tsang, 2002) and relationship-specific knowledge about their business partners (Johanson & Vahlne, 2003, 2009). These direct and indirect local business associates are therefore an important source of learning in the process of overcoming the LoO. In this regard, absorptive capacity is very important. Cohen and Levinthal have shown that developing absorptive capacity requires both knowledge overlap and knowledge diversity (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). Knowledge overlap with the knowledge bases of local partners can serve as the foundation for effective communication. It enhances a deeper understanding of the information and knowledge being transferred and facilitates identifying new opportunities (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). Knowledge overlap can be based on common technical, managerial, and institutional experience, but at the same time, heterogeneity in partners’ knowledge bases is also essential if useful new linkages and associations are to be created (Simon, 1985). Excessive overlap minimizes the diversity that is so helpful for generating novel ideas and solutions (Li, Tian, & Wan, 2015; Li & Wan, 2016). EMNEs should thus try to select business partners with an appropriate level of knowledge overlap.

The closeness of relationships and trust between partners also influence absorptive capacity. Closer relationships and greater trust facilitate knowledge transfer (Li & Hambrick, 2005). Parties with close ties tend to develop relationship-specific heuristics that can promote the transfer of complex and tacit knowledge (Hansen, 1999; Uzzi, 1997). Trust alleviates concerns about the appropriation and misuse of knowledge. A trusting relationship between international business partners can develop from prior exchanges or through personal connections between the firms’ executives.

Learning can also be influenced by the relative status of business partners and the power dynamics involved. International partners of unequal status and power may be prone to coopetition in which engagement of the weaker party may be curbed by concerns about unwanted knowledge dissipation to the more powerful (Yli-Renko, Autio, & Sapienza, 2001). This problem may be especially salient for EMNEs entering more developed economies. In learning from local powerful partners, EMNEs also need to manage the risk of unwanted knowledge dissipation. To enhance their knowledge overlap with local partners, EMNEs may recruit professionals educated and trained in developed countries and local returnees from overseas. They can also try to build relationships with local firms that intend to penetrate their home market. China has used such techniques intensively (Tian et al., 2018) but, interestingly, when Chinese multinationals have moved into mature markets with strong and long-established business networks, as is the case in Europe, they have had to modify their preferred guanxi type of relationships and recruit experienced European managers capable of establishing network relationships (Chen, 2017). However, there are limits to such practices. Puffer, McCarthy, Jaeger, and Dunlap (2013) analyzed the Chinese guanxi, the Brazilian jeitinho, the Russian blat or sviazi, and the Indian jaan-pehchaan practices, and found that their use only facilitates relationships aimed at expansion into foreign markets with a similar cultural-cognitive mindset and similar informal institutions. Elsewhere, these practices can actually inhibit internationalization. Guercini et al. (2017) have shown that ethnic networks facilitate the creation of business networks in the early stages of internationalization, but that they have little impact on the establishment of connections with suppliers and consumers.

Implication 1:

EMNEs can improve their absorptive capacity and enhance learning from business partners by selecting partners with the proper level of knowledge overlap, developing close relationships and trust with them and managing the risk of unwanted knowledge dissipation if the partners are more powerful.

Local Consumers

Apart from business partners, local consumers are also essential sources of knowledge for internationalizing EMNEs. A demand-based perspective (Priem, 2007; Xie & Li, 2015) suggests that, apart from traditional value-capturing tactics, firms can also gain competitive advantage by creating value and improving the consumer benefit experienced (CBE) (Priem, Butler, & Li, 2013). For EMNEs, this involves learning from local consumers, which is also essential for overcoming the LoO (Xie & Li, 2015; Zhang, Xie, Li, & Cheng, 2019). Effective learning can help a firm improve the CBE of host-country consumers in various ways. First, EMNEs can tap into local consumers’ knowledge about related products and services and use that knowledge to build connections with their own products. They can create an ecosystem. This will facilitate local consumers’ getting familiar with the firm’s new products and services and create value via the synergy generated in the ecosystem (Li, Chen, Yi, Mao, & Liao, 2019a).

EMNEs should also make efficient use of peer- or expert-based selection systems to lower consumers’ search costs (Priem, 2007). A firm can reduce search costs for consumers via traditional promotion and advertising, but in a digital economy it can be more effective and efficient to use peer-review systems or platforms (Li et al., 2019a). The systems can be either local or global, but they should be widely used and regarded as reliable by local consumers.

Finally, an entering firm can build up local consumers’ knowledge of its products by creating trial opportunities. A typical example is China’s smartphone company Xiaomi, which opened Xiaomi stores in emerging markets such as India where potential consumers can try their various products and get assistance. Such managerial practices also provide firms with first-hand experience with local consumers to learn about their specific requirements.

Implication 2:

EMNEs can improve their absorptive capacity to learn from local consumers and at the same time increase consumer benefits by tapping into local consumers’ knowledge of related products and services, using peer- or expert-based recommendation systems to reduce search costs and helping local consumers build up product-specific consumption experience.

Local Communities

Doing business in a foreign country embeds a firm in a new social environment where it needs to deal with and reconcile the complex interests of different stakeholders in the local community. Failing to attend to the interests and requirements of local communities may create social pressures and business obstacles. For instance, there have been frequent cases of boycotts against products made in foreign sweatshops. Therefore, learning from stakeholders in the host country can be critical for the survival and success of a new entrant (Darendeli & Hill, 2016; Laplume, Sonpar, & Litz, 2008).

Three dimensions of learning from a local community may be particularly important. One is recognizing and building on local employees’ potential as boundary spanners. The essential role of boundary spanners in stimulating information exchange has long been recognized (e.g., Tushman & Scanlan, 1981). Their knowledge can be a critical determinant of a firm’s absorptive capacity (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). Social, economic, and cultural differences from those of a firm’s home country may make a firm’s management practices ineffective or even misguided. In order to correctly evaluate and attend to local stakeholders’ expectations, EMNEs may find the knowledge possessed by local employees very helpful.

An entrant should also pay attention to potential conflict in the interests of home- and host-country stakeholders (Li et al., 2019b). This may require “contextualized” measures to manage the relationships with different parties.

Entrants can also enhance their learning from local communities by proactively making socially responsible investments outside of their main business activities. It has been noted that foreign investors can be reluctant to get involved in such activities and that they are less likely than local economic actors to invest effectively (Campbell, Eden, & Miller, 2012). This approach can, however, be very effective in reducing the LoO. Socially responsible investing helps build a favorable image in the host country and can motivate important stakeholders to cooperate. Learning will often also be facilitated.

Implication 3:

EMNEs can improve their absorptive capacity and enhance learning from local communities by leveraging the knowledge of local employees, paying special attention to potential conflicts of interest between home- and host-country stakeholders, and proactively engaging in socially responsible local investments.

Absorptive Capacity, Internationalization Process, and Performance

Absorptive capacity serves as a key concept in unraveling how learning through relationships leads to more successful internationalization. J&V’s 1977 and 2009 models do not explicitly illustrate how the internationalization process translates into MNE performance. Santangelo and Meyer (2017), in their counterpoint to the 2017 revision of the Uppsala model, explained the influence on internationalization performance through an evolutionary perspective. They suggested that an MNE’s performance is determined by the selection outcome that best fits the environment. Therefore, firms making more “path-breaking resource commitments” in internationalization process will be more likely to have a higher performance, but at the same time also bear more risk of incurring large losses or being forced to exit. From a capability-building perspective, however, novel resource commitments that lead to stronger firm capabilities can improve performance both by enhancing the expected positive outcome from these resource commitments and by actually lowering the risk of losses.

Greater absorptive capacity enhances learning, which in turn facilitates the accumulation of more extensive, accurate, and relevant relationship-specific knowledge. As is illustrated in J&V’s 2009 model, knowledge accumulation substantially influences EMNEs’ internationalization and helps them overcome the LoO. Specifically, more efficient and accurate learning from local business partners, consumers, and communities can help firms better identify and respond to local business opportunities. Deeper knowledge about these different stakeholders helps MNEs formulate their strategies and tactics accordingly, leading to smoother and more efficient strategy implementation. With similar resource commitments made in the local market, a firm with higher absorptive capacity and more knowledge accumulation than a rival will therefore be more likely to achieve better performance. Effective learning, on the other hand, also mitigates the risk faced by MNEs in the host-country market. They can better evaluate any operational and financial hazards using the information provided by business partners; more accurately and timely detect changes in consumer preferences; and be more attuned to the social, institutional, or culture pressures in the host country. The ability to derive more benefits from resource commitments and to better control risk of failure eventually translates into better performance internationally.

Implication 4:

Greater absorptive capacity will enhance learning from local business partners, consumers, and communities, which can lead to more successful internationalization.

Influence of the Institutional Environments

The institutional environment is an important contingency in the above proposed processes. It impacts both learning through relationships and how better absorptive capacity is linked to more successful internationalization.

Despite J&V’s assumption that institutional and cultural issues are less relevant when internationalization follows a business network strategy, an emerging economy firm’s gaining access to host-country business networks is strongly influenced by institutional parameters. On the negative side, the weak institutional environments of emerging economies handicap any firm seeking to join business networks composed of firms from developed countries. Creating trust is more essential, but it is also difficult to achieve. To be accepted in such networks, an emerging country firm must prove it will comply with, and perhaps even go beyond, the standards of the local business community. In their favor, emerging-country firms can often count on home government support (Ciravegna, Lopez, & Kundu, 2014). This might involve diplomacy smoothing their acceptance, financing, institutional guidance, or exhibitions and commercial missions promoting the country’s firms products and brands. Such government support can reduce costs and risks, augment a firm’s bargaining power, enhance learning, and generally facilitate a firm’s entry into business networks. That will facilitate and streamline internationalization.

Visible cases include Chinese firms because the Chinese government openly directs their internationalization and influences the decision-making of both state-owned and non-state-owned firms in its expression of state capitalism (Li et al., 2019b; Li, Liu, & Qian, 2019c). Traditional mechanisms to reduce LoO, such as the creation of foreign information offices and various forms of promotion are combined with financial support. Government and firms work in tandem in sectors where the government thinks there is a strategic interest (Holtbrügge & Berning, 2018; Santangelo & Meyer, 2011) or when the internationalizing firm is a state-owned enterprise (Li et al., 2019b; Luo, Xue, & Han, 2010). In such cases, the Chinese government might finance a firm’s entry into foreign business networks through an acquisition (Li et al., 2019b; Wei, Clegg, & Ma, 2015) or a greenfield investment. The Chinese government’s motivation for most such investments has been to bring managerial and technological knowledge back home, as Luo and Tung (2007) have described. The impact of outsidership may be considerably reduced in the case of asset-seeking, foreign acquisitions, as the investing Chinese firm’s dependence on the host-country’s business network might be limited. However, the political dimension associated with the expansion of Chinese firms sometimes raises institutional sensitivities and public concerns in the host countries, as exemplified by the 2019 Huawei case. In May 2019, the Commerce Department of the United States put Huawei and its multiple subsidiaries on the trade blacklist, during the heightened U.S.–China trade tension. They are barred from trading with U.S. companies without governmental approval for the concern of potential threat this Chinese telecommunications giant put on the information security of the U.S. Being banned from purchasing elements and components from its major American suppliers, Huawei’s global businesses were significantly affected. The case attests to the salience of the host country’s security concern and bilateral political dynamics in global business.

For the Brazilian government, internationalization is not a priority, but even so Brazilian firms have received considerable funds for their expansion through the acquisition of developed-market multinationals and brands. However, in those cases, the post-acquisition integration was sometimes challenging due to the need to gain internal legitimacy in the acquired firm and external legitimacy in the relevant business networks (Fleury, Fleury, & Borini, 2013).

In host countries, the relationships among local parties and knowledge, which has been developed locally, are embedded in the economy’s institutional environment (Meyer & Peng, 2016). Learning must therefore adapt itself to the specific institutional context. The substantial differences between the institutional environments of the host and home countries can make learning very challenging for an EMNE (Lundan & Li, 2019; Xie & Li, 2018). The local institutional context will normally impact the content, cost, and efficiency of learning and shape how absorptive capacity is built up. A dynamic and uncertain host-country environment will influence how firms interact with their business partners and attend to local consumer needs, and it will shape the local community’s expectations. A dynamic institutional environment can make the knowledge overlap between international partners especially important, as overlap can help them better keep up with rapid changes (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). A dynamic and uncertain environment will at the same time make it harder for an entering firm to improve the consumer benefit experienced because the changes in consumer demand and tastes will tend to be frequent and less predictable, and an entrant must, at the same time, consider institutional changes in its home country, as changes in regulations or government policies there can create both opportunities and threats.

As for how absorptive capacity translates into actual performance, the institutional context can also play an essential role (Lundan & Li, 2019). Effective learning from multiple parties will help firms accumulate the knowledge they need to overcome the LoO, but a favorable network position alone cannot guarantee strong performance. Shocks and constraints in the institutional environments may create obstacles to profitability or even survival for a foreign firm. Political tension between the host and home country is an obvious example, and Huawei is again a pertinent case. As mentioned before, Huawei has suffered from boycotts from U.S. enterprises which cut off the supply of some essential elements for its products. This boycott is to a large extent a consequence of the trade war between China and the United States. So in discussing how absorptive capacity builds up and how it influences internationalization, it is necessary to account for the effects of the external institutional environments.

Implication 5:

Learning from local business partners, consumers, and communities, and how absorptive capacity relates to internationalization performance, are all contingent on characteristics of the institutional environments of the home and host countries.

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

The Learning Perspective

EMNEs can overcome the LoO by building up their capacity to absorb knowledge from their host-country networks, but this mechanism to some extent relies on embeddedness in the host country. One question is to what extent better absorptive capacity can directly help EMNEs build stronger and more-enduring connections with local business partners, consumers, or other stakeholders. Firms with greater absorptive capacity are better able to recognize and appreciate new information and opportunities, which implies an open mindset and more effort to be involved in local networks. Such firms are more likely to be successful in connecting with local actors and overcoming the LoO. This perspective also suggests that building local relationships and absorptive capacity would be mutually reinforcing and recursive, which provides subject matter for future scholarly examination.

In addition, scholars have also pointed out the importance of learning within the boundary of MNEs (Hutzschenreuter & Matt, 2017). An MNE with prior internationalization experience should accumulate knowledge that is distributed among its different divisions or subsidiaries. MNEs can, in principle, manage and synthesize the knowledge embedded in their subsidiaries to facilitate further international expansion. How headquarters actually do internalize and integrate knowledge from various subsidiaries deserves deeper examination. Moreover, it remains to be explored to what extent the knowledge accumulated by subsidiaries in specific countries or regions is non-location bound and can effectively be applied in other contexts. Here, trying to deploy prior learning that is not applicable in a new market may even create new challenges.

Another potential question with regard to the learning perspective is the downside of learning, or the “liability of insidership” (i.e., the cost of being an insider). If we view learning and networking as mutually reinforcing, we should ask the question whether there would be any costs of local network ‘lock-in’, such as costs associated with inertia, path dependence, and restricted access to new partners (Jiang, Xia, Cannella, & Xiao, 2018). Indeed, researchers have shown that learning from experience is not always optimal, and can entail negative transfers, defined as learning the wrong lessons from prior experience (Haleblian & Finkelstein, 1999). It can also lead to superstitious learning where “[the] subjective experiencing of learning is compelling, but the connection between action and performance is mis-specified” (Levitt & March, 1988: 325). Any ‘lock-in’ will then not only reduce a firm’s adaptability but also inhibit the identification of new opportunities (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). Therefore, future research should explore the potential performance barriers and threats arising from over-embeddedness in a host country’s networks. Strategies and practices that can help EMNEs overcome these barriers would also be an important topic for research. What are the consequences of over-embeddedness? Will prolonged partnering with specific firms dampen innovation? How can EMNEs maintain relationships with existing partners in the host country while getting connected with new, more diverse partners?

Social Network Theory

One central argument of social network theory is that non-redundant relationships are associated with more diverse information (Burt, 1992). While there can be a variety of knowledge flowing in a network, a firm’s position and the network structure will determine what portion of this knowledge the firm can eventually access (Singh, Kryscynski, Li, & Gopal, 2016). Despite J&V’s emphasis on networks in their 2009 paper, they made little reference to the key constructs in social network theory such as network positions, structural holes, and the density of a network’s structure. For an EMNE new to a host country and potentially suffering from the disadvantages of being a late-comer (Awate et al., 2012; Luo & Tung, 2007), issues such as partner selection, the effects of network structure on knowledge transfer and application, and the dynamic evolution of networks can be very important. These are issues that have been studied extensively in the social network literature (Petricevic & Verbeke, 2019). There are significant opportunities for advancing LoO research by developing more refined hypotheses based on the core constructs of social network theory.

In developing relationships in a host market, the first question for an EMNE is probably with whom to collaborate. Social network theory suggests the importance of taking into consideration not only the level of trust based on prior interactions (Li, Eden, Hitt, & Ireland, 2008) but also the network positions of prospective partners. For example, network brokers typically have diverse ties and are a rich source of information. It would thus be interesting to investigate whether connecting with brokers is, in relative terms, the most effective approach for overcoming LoO. How do relational and structural aspects of partners jointly influence the process of overcoming LoO? Furthermore, established relationships need to be carefully managed, otherwise those ties may be dissolved (Jiang et al., 2018). What types of ties are more likely to survive? Are there any patterns of network evolution discernable in more-developed host markets? Social network theory should have some potential to address those questions and provide guidance for EMNEs in managing their network relationships.

Global value chains (Gereffi, Humphrey, & Sturgeon, 2005) are another conceptual approach to understanding the creation and dynamics of business networks. Of particular interest is the recent discussion in JIBS aimed at better understanding the importance of the middle ground between markets and hierarchies in today’s international business landscape (Benito, Petersen, & Welch, 2019; Strange & Humphrey, 2019). Issues such as trust and flexibility take center stage, when qualifying the nature of and the rationale for business relationships.

Institutional Theory

The increasing prominence of EMNEs worldwide has triggered the development of new approaches in the institutional theory domain, derived from different theoretical roots (Aguilera and Grøgaard 2019). Both the (macro-level) economics tradition of viewing institutions as setting and enforcing the rules of the game, and the sociological tradition, emphasizing a concern for social legitimacy imposed by institutions, have been influential in IB research (Meyer & Peng, 2016). The (macro-level) economics perspective implies that institutional characteristics should influence the effectiveness of EMNEs’ learning from local actors and hence the process of internationalization, but this perspective promotes a relatively static approach, viewing firms as passive respondents and institutions as stable. In fact, firms can be proactive and even institution-seeking (Paik & Zhu, 2016), and institutions can to some extent be shaped by the actions of MNEs and their home-country governments. Given the proactivity of investing firms from emerging markets and the support they receive from their home governments (Luo & Tung, 2007), it is reasonable to allow for dynamism in the institutional framework when analyzing the internationalization of EMNEs. More specifically, how and to what extent can EMNEs influence local institutions to help them get involved in local networks and learn more effectively? For example, some Chinese firms are taking an active role in defining technology standards. They may play a critical role in determining the rules of future technology governance. It is worth examining how such efforts can affect the firms’ network positions in advanced markets as well as their subsequent learning and performance internationally.

Neo-institutional theory focuses on the legitimacy pressures EMNEs face. This issue is particularly important on the community level. Despite various definitions of community based on country-of-origin, industry and location (e.g., Li, Yang, & Yue, 2007; Marquis & Tilcsik, 2016), it is still not clear what constitutes the community of an EMNE in a host country and to which groups EMNEs should refer, in order to earn legitimacy. In fact, the requirements imposed by different communities will vary and may even conflict, which might discourage an EMNE from becoming an insider in host markets. Future research should seek to define the boundaries of EMNEs’ communities and the implications for their strategies.

Another promising direction relates to the complexity of the belief systems that guide firms’ behavior (Rao, Monin, & Durand, 2003). EMNEs are likely to be confronted with conflicting or competing systems as they globalize. To balance between becoming an insider in an overseas market and keeping a share of the domestic market, EMNEs must sometimes navigate among different (and sometimes conflicting) institutional logics.

Although the importance of the institutional environment is almost universally recognized, future research might fruitfully attempt to elaborate on which kinds of impact can take place and the mechanisms involved. What institutional characteristics in a host country most significantly influence an EMNE’s development? How can building and maintaining business relationships be affected by institutional characteristics and how should EMNEs best manage the risks created by various institutional environments?

Resource Dependence Theory

J&V, in their 2009 exposition, emphasized the development of close relationships and trust between partners in order to facilitate learning. However, another aspect of developing and maintaining relationships is the mutual dependence and power dynamics involved, and those have not yet been adequately considered. Resource dependence theory (Hillman, Withers, & Collins, 2009; Pfeffer & Salancik, 2003) suggests that organizations seek to reduce their dependence on powerful external parties. The two key considerations are the extent of mutual dependence and any power imbalance (Casciaro & Piskorski, 2005). Mutual dependence is largely governed by the extent of embeddedness and of mutualism (Gulati & Sytch, 2007). It thus tends to promote closer relationships. Power imbalance, on the other hand, can create problems such as expropriation by business partners (Emerson, 1962). Closer relationships with – and increased dependence on – certain partners can grant those partners greater power, which may increase the risk of unintended knowledge dissipation and appropriation. So apart from pursuing learning objectives, we would expect EMNEs to also proactively manage their dependence on local business partners. But how can they best balance the benefits of close relationships against the risks of greater dependence? Should EMNEs build relationships with multiple partners to better manage their dependence on the external environment given the resource constraints they face? How can EMNEs increase their own power over their business partners?

MNE Structure and Design

J&V focused on learning as the motivation for constructing relationships, but building absorptive capacity and learning also require appropriate internal organization. Such internal organization can extend to the governance of parent–subsidiary relationships. Structure is important because it determines to what extent individuals within a firm can communicate and exchange information and knowledge. It therefore influences how the knowledge bases of individuals are integrated and contribute to the firm’s absorptive capacity. The importance of learning within MNEs from the multiple subsidiaries has been pointed out in the extant literature (Hutzschenreuter & Matt, 2017). It remains to be explored in the EMNE context what the best parent–subsidiary structure is for promoting learning from relationships (Verbeke & Kenworthy, 2008). How does the parent–subsidiary relationship affect overcoming the outsider’s liabilities in a host country? What kind of organizational design best favors learning from different partners? To what extent does a supposedly best design depend on a firm’s business relationships with different partners?

CONCLUSION

This paper has presented a capability-building perspective on J&V’s 2009 study. It offers several takeaways that may prove useful to IB researchers and managers,

The 2009 Uppsala model is centered on relationships in business networks rather than on conventional market entry considerations. This relationship-based perspective makes more explicit and specific how firms can overcome obstacles to their internationalization. Learning from the local market as proposed in the 1977 model provides only general guidance, without specifying which market components to learn from and how. In treating markets as networks of relationships, the 2009 model generates concrete implications about the sources of – and approaches to – learning: Entrants should overcome the LoO by learning from their partners in network relationships. This view can help generate more precise theoretical predictions and more actionable implications for managerial practice. Moreover, this change from the original model also better suits today’s global business environment. Networking and relationship-based internationalization have become more important than ever, given today’s greater volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity (VUCA conditions) in the firm’s economic, political, social, innovation-related, and broader institutional environments (Tulder, Verbeke & Jankowska, 2019).

The liabilities of outsidership appear to be especially salient for firms from emerging economies. These liabilities make the relationship-based perspective more applicable to them, for two reasons. First, they are confronted with a more challenging environment. They often enjoy neither initial competitive advantage, nor superior technology. EMNEs tend to start from second-tier network positions. They tend to lack legitimacy, thus showing a clear LoO. For firms in a weak competitive position, it is fundamentally important to manage their resource dependence and uncertainties through cooperative relationships. Therefore, building and maintaining stable partnerships with local entities is especially important for EMNEs entering into more developed economies if they are to gain a more favorable network position and overcome the liabilities of outsidership.

A second consideration is that absorptive capacity could be viewed as a core competence for overcoming outsidership liabilities. Its presence substantially impacts learning from relationships with different local entities, so it is a capability to which EMNEs need to attach great importance and which they need to keep reinforcing in their internationalization process. Absorptive capacity will likely be even more critical when the external market is fraught with VUCA challenges, as is the case today.

Notes

-

1

Although China is no longer regarded as an emerging economy by some researchers, it was considered so (and part of the BRICs) when the JV article was published and the subsequent studies were conducted.

REFERENCES

Aguilera, R. V., & Grøgaard, B. 2019. The dubious role of institutions in international business: A road forward. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(1): 20–35.

Amsden, A. H. 1989. Asia’s next giant: Late industrialization in South Korea. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Amsden, A. H. 2009. Does firm ownership matter? POEs vs. FOEs in the developing world. In R. Ramamurti & J. V. Singh (Eds.), Emerging multinationals in emerging markets (pp. 64–78). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Awate, S., Larsen, M. M., & Mudambi, R. 2012. EMNE catch-up strategies in the wind turbine industry: Is there a trade-off between output and innovation capabilities? Global Strategy Journal, 2(3): 205–223.

Barkema, H. G., Bell, J. H., & Pennings, J. M. 1996. Foreign entry, cultural barriers, and learning. Strategic Management Journal, 17(2): 151–166.

Benito, G. R., Petersen, B., & Welch, L. S. 2019. The global value chain and internalization theory. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(8): 1414–1423.

Best, M. H. 1990. The new competition: Institutions of industrial restructuring. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Burt, R. 1992. Structural holes: The social structure of competition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Campbell, J. T., Eden, L., & Miller, S. R. 2012. Multinationals and corporate social responsibility in host countries: Does distance matter? Journal of International Business Studies, 43(1): 84–106.

Casciaro, T., & Piskorski, M. J. 2005. Power imbalance, mutual dependence, and constraint absorption: A closer look at resource dependence theory. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(2): 167–199.

Chen, J. 2017. Internationalization of Chinese firms: What role does Guanxi play for overcoming their liability of outsidership in developed markets? Thunderbird International Business Review, 59(3): 367–383.

Ciravegna, L., Lopez, L., & Kundu, S. 2014. Country of origin and network effects on internationalization: A comparative study of SMEs from an emerging and developed economy. Journal of Business Research, 67(5): 916–923.

Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. 1990. Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1): 128–152.

Coviello, N., Kano, L., & Liesch, P. W. 2017. Adapting the Uppsala model to a modern world: Macro-context and microfoundations. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(9): 1151–1164.

Cuervo-Cazurra, A. 2016. Multilatinas as sources of new research insights: The learning and escape drivers of international expansion. Journal of Business Research, 69(6): 1963–1972.

Curran, L., & Ng, L. K. 2018. Running out of steam on emerging markets? The limits of MNE firm-specific advantages in China. Multinational Business Review, 26(3): 207–224.

Darendeli, I. S., & Hill, T. L. 2016. Uncovering the complex relationships between political risk and MNE firm legitimacy: Insights from Libya. Journal of International Business Studies, 47(1): 68–92.

De Clercq, D., Sapienza, H. J., Yavuz, R. I., & Zhou, L. 2012. Learning and knowledge in early internationalization research: Past accomplishments and future directions. Journal of Business Venturing, 27(1): 143–165.

Emerson, R. M. 1962. Power-dependence relations. American Sociological Review, 27, 31–41.

Ferrucci, L., Gigliotti, M., & Runfola, A. 2018. Italian firms in emerging markets: Relationships and networks for internationalization in Africa. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 30(5): 375–395.

Fiedler, A., Fath, B. P., & Whittaker, D. H. 2017. Overcoming the liability of outsidership in institutional voids: Trust, emerging goals, and learning about opportunities. International Small Business Journal, 35(3): 262–284.

Fleury, A., Fleury, M. T. L., & Borini, F. M. 2013. The Brazilian multinationals’ approaches to innovation. Journal of International Management, 19(3): 260–275.

Fornes, G., & Cardoza, G. 2019. Internationalization of Chinese SMEs: The perception of disadvantages of foreignness. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 55(9): 2086–2105.

Forsgren, M., Holm, U., & Johanson, J. 2015. Knowledge, networks and power—The Uppsala School of International Business. In M. Forsgren, U. Holm, & J. Johanson (Eds.), Knowledge, networks and power (pp. 3–38). Berlin: Springer.

Gereffi, G., Humphrey, J., & Sturgeon, T. 2005. The governance of global value chains. Review of International Political Economy, 12(1): 78–104.

Guercini, S., Milanesi, M., & Dei Ottati, G. 2017. Paths of evolution for the Chinese migrant entrepreneurship: A multiple case analysis in Italy. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 15(3): 266–294.

Gulati, R., & Sytch, M. 2007. Dependence asymmetry and joint dependence in interorganizational relationships: Effects of embeddedness on a manufacturer’s performance in procurement relationships. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(1): 32–69.

Haleblian, J., & Finkelstein, S. 1999. The influence of organizational acquisition experience on acquisition performance: A behavioral learning perspective. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(1): 29–56.

Hansen, M. T. 1999. The search-transfer problem: The role of weak ties in sharing knowledge across organization subunits. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(1): 82–111.

Herstad, S. J., Aslesen, H. W., & Ebersberger, B. 2014. On industrial knowledge bases, commercial opportunities and global innovation network linkages. Research Policy, 43(3): 495–504.

Hillman, A. J., Withers, M. C., & Collins, B. J. 2009. Resource dependence theory: A review. Journal of Management, 35, 1404–1427.

Holtbrügge, D., & Berning, S. C. (2018). Market entry strategies and performance of Chinese firms in Germany: The moderating effect of home government support. Management International Review, 58(1): 147–170.

Hutzschenreuter, T., & Matt, T. 2017. MNE internationalization patterns, the roles of knowledge stocks, and the portfolio of MNE subsidiaries. Journal of International Business Studies, 48, 1131–1150.

Jiang, H., Xia, J., Cannella, A. A., & Xiao, T. 2018. Do ongoing networks block out new friends? Reconciling the embeddedness constraint dilemma on new alliance partner addition. Strategic Management Journal, 39(1): 217–241.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J.-E. 1977. The internationalization process of the firm—A model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. Journal of International Business Studies, 8(1): 23–32.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J.-E. 2003. Business relationship learning and commitment in the internationalization process. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 1(1): 83–101.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J.-E. 2009. The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(9): 1411–1431.

Kingkaew, S., & Dahms, S. 2019. Explaining autonomy variations across value-chain activities in foreign-owned subsidiaries. Thunderbird International Business Review, 61(2): 425–438.

Kontinen, T., & Ojala, A. 2011. Network ties in the international opportunity recognition of family SMEs. International Business Review, 20(4): 440–453.

Laplume, A. O., Sonpar, K., & Litz, R. A. 2008. Stakeholder theory: Reviewing a theory that moves us. Journal of Management, 34(6): 1152–1189.

Levitt, B., & March, J. G. 1988. Organizational learning. Annual Review of Sociology, 14(1): 319–338.

Li, J. 2011. Rethinking international and global strategy. Global Strategy Journal, 1(3–4): 275–278.

Li, D., Eden, L., Hitt, M. A., & Ireland, R. D. 2008. Friends, acquaintances, or strangers? Partner selection in R&D alliances. Academy of Management Journal, 51(2): 315–334.

Li, J., & Hambrick, D. C. 2005. Factional groups: A new vantage on demographic faultlines, conflict, and disintegration in work teams. Academy of Management Journal, 48(5): 794–813.

Li, J., Chen, L., Yi, J., Mao, J., & Liao, J. 2019a. Ecosystem-specific advantages in international digital commerce. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(9): 1448–1463.

Li, J., Li, P., & Wang, B. 2019b. The liability of opaqueness: State ownership and the likelihood of deal completion in international acquisitions by Chinese firms. Strategic Management Journal, 40(2): 303–327.

Li, J., Liu, B., & Qian, G. 2019c. The belt and road initiative, cultural friction and ethnicity: Their effects on the export performance of SMEs in China. Journal of World Business, 54(4): 350–359.

Li, J., Tian, L., & Wan, G. 2015. Contextual distance and the international strategic alliance performance: A conceptual framework and a partial meta-analytic test. Management and Organization Review, 11(2): 289–313.

Li, J., & Wan, G. 2016. China’s cross-border mergers and acquisitions: A contextual distance perspective. Management and Organization Review, 12(3): 449–456.

Li, J., Yang, J. Y., & Yue, D. R. 2007. Identity, community, and audience: How wholly owned foreign subsidiaries gain legitimacy in China. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1): 175–190.

Lu, J., Liu, X., Wright, M., & Filatotchev, I. 2014. International experience and FDI location choices of Chinese firms: The moderating effects of home country government support and host country institutions. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(4): 428–449.

Lundan, S. M., & Li, J. 2019. Adjusting to and learning from institutional diversity: Toward a capability-building perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(1): 36–47.

Luo, Y., & Peng, M. W. 1999. Learning to compete in a transition economy: Experience, environment, and performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 30(2): 269–295.

Luo, Y., & Tung, R. L. 2007. International expansion of emerging market enterprises: A springboard perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(4): 481–498.

Luo, Y., Xue, Q., & Han, B. 2010. How emerging market governments promote outward FDI: Experience from China. Journal of World Business, 45(1): 68–79.

Mainela, T., Puhakka, V., & Servais, P. 2014. The concept of international opportunity in international entrepreneurship: A review and a research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 16(1): 105–129.

Marquis, C., & Tilcsik, A. 2016. Institutional equivalence: How industry and community peers influence corporate philanthropy. Organization Science, 27(5): 1325–1341.

Meyer, K. E., & Peng, M. W. 2016. Theoretical foundations of emerging economy business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 47(1): 3–22.

Paik, Y., & Zhu, F. 2016. The impact of patent wars on firm strategy: Evidence from the global smartphone industry. Organization Science, 27(6): 1397–1416.

Petricevic, O., & Verbeke, A. 2019. Unbundling dynamic capabilities for inter-organizational collaboration: The case of nanotechnology. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 26(3): 422–448.

Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. R. 2003. The external control of organizations: A resource dependence perspective. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Pitelis, C. N., & Teece, D. J. 2010. Cross-border market co-creation, dynamic capabilities and the entrepreneurial theory of the multinational enterprise. Industrial and Corporate Change, 19(4): 1247–1270.

Priem, R. L. 2007. A consumer perspective on value creation. Academy of Management Review, 32(1): 219–235.

Priem, R. L., Butler, J. E., & Li, S. 2013. Toward reimagining strategy research: Retrospection and prospection on the 2011 AMR decade award article. Academy of Management Review, 38(4): 471–489.

Puffer, S. M., McCarthy, D. J., Jaeger, A. M., & Dunlap, D. 2013. The use of favors by emerging market managers: Facilitator or inhibitor of international expansion? Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 30(2): 327–349.

Rahaman, M. M. 2016. Chinese import competition and the provisions for external debt financing in the US. Journal of International Business Studies, 47(8): 898–928.

Rao, H., Monin, P., & Durand, R. 2003. Institutional change in Toque Ville: Nouvelle cuisine as an identity movement in French gastronomy. American Journal of Sociology, 108(4): 795–843.

Ronen, S., & Shenkar, O. 2013. Mapping world cultures: Cluster formation, sources and implications. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(9): 867–897.

Rugman, A., Verbeke, A., & Yuan, W. 2011. Re-conceptualizing Bartlett and Ghoshal’s classification of national subsidiary roles in the multinational enterprise. Journal of Management Studies, 48(2): 253–277.

Santangelo, G. D., & Meyer, K. E. 2011. Extending the internationalization process model: Increases and decreases of MNE commitment in emerging economies. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(7): 894–909.

Santangelo, G. D., & Meyer, K. E. 2017. Internationalization as an evolutionary process. Journal of International Business Studies, 48, 1114–1130.

Shen, Z., & Puig, F. 2018. Spatial dependence of the FDI entry mode decision: Empirical evidence from emerging market enterprises. Management International Review, 58(1): 171–193.

Si, Y., & Liefner, I. 2014. Cognitive distance and obstacles to subsidiary business success: The experience of Chinese companies in Germany. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie, 105(3): 285–300.

Simon, H. A. 1985. What we know about the creative process. Frontiers in Creative and Innovative Management, 4, 3–22.

Singh, H., Kryscynski, D., Li, X., & Gopal, R. 2016. Pipes, pools, and filters: How collaboration networks affect innovative performance. Strategic Management Journal, 37(8): 1649–1666.

Strange, R., & Humphrey, J. 2019. What lies between market and hierarchy? Insights from internalization theory and global value chain theory. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(8): 1401–1413.

Sun, P., Mellahi, K., & Thun, E. 2010. The dynamic value of MNE political embeddedness: The case of the Chinese automobile industry. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(7): 1161–1182.

Sun, S. L., Peng, M. W., Ren, B., & Yan, D. 2012. A comparative ownership advantage framework for cross-border M&As: The rise of Chinese and Indian MNEs. Journal of World Business, 47(1): 4–16.

Tian, Y. A., Nicholson, J. D., Eklinder-Frick, J., & Johanson, M. 2018. The interplay between social capital and international opportunities: A processual study of international ‘take-off’ episodes in Chinese SMEs. Industrial Marketing Management, 70, 180–192.

Tsang, E. W. 2002. Acquiring knowledge by foreign partners from international joint ventures in a transition economy: Learning-by-doing and learning myopia. Strategic Management Journal, 23(9): 835–854.

Tung, R. L., & Verbeke, A. 2010. Beyond Hofstede and GLOBE: Improving the quality of cross-cultural research. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(8): 1259–1274.

Tushman, M. L., & Scanlan, T. J. 1981. Boundary spanning individuals: Their role in information transfer and their antecedents. Academy of Management Journal, 24(2): 289–305.

Uzzi, B. 1997. Social structure and competition in interfirm networks: The paradox of embeddedness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 35–67.

van Tulder, R., Verbeke, A., & Jankowska, B. (Eds.). 2019. International Business in a VUCA World. Bingley: Emerald.

Verbeke, A., & Kenworthy, T. P. 2008. Multidivisional vs metanational governance of the multinational enterprise. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(6): 940–956.

Wei, T., Clegg, J., & Ma, L. 2015. The conscious and unconscious facilitating role of the Chinese government in shaping the internationalization of Chinese MNCs. International Business Review, 24(2): 331–343.

Xie, Z., & Li, J. 2015. Demand heterogeneity, learning diversity and innovation in an emerging economy. Journal of International Management, 21(4): 277–292.

Xie, Z., & Li, J. 2018. Exporting and innovating among emerging market firms: The moderating role of institutional development. Journal of International Business Studies, 49(2): 222–245.

Yli-Renko, H., Autio, E., & Sapienza, H. J. 2001. Social capital, knowledge acquisition, and knowledge exploitation in young technology-based firms. Strategic Management Journal, 22(6–7): 587–613.

Yu, Y., & Sharma, R. R. 2016. Dancing with the stars: What do foreign firms get from high-status local partners? Management Decision, 54(6): 1294–1319.

Zhang, X., Xie, L., Li, J., & Cheng, L. 2019. “Outside in”: Global demand heterogeneity and dynamic capabilities of multinational enterprises. Journal of International Business Studies. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-019-00252-6.

Zhang, H., Young, M. N., Tan, J., & Sun, W. 2018. How Chinese companies deal with a legitimacy imbalance when acquiring firms from developed economies. Journal of World Business, 53(5): 752–767.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Editor-in-Chief Alain Verbeke and two anonymous reviewers for their insightful feedback during the review process. The research is supported in part by the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (HKUST #16505817 and #16507219). We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Charles Chen, Afonso Fleury, Juno Li, and Arden Leung to this commentary.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Fleury, M.T.L. Overcoming the liability of outsidership for emerging market MNEs: A capability-building perspective. J Int Bus Stud 51, 23–37 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-019-00291-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-019-00291-z