Abstract

This article explores the use of favors by emerging market managers, the impact of using favors on their firms’ growth, legitimacy, and reputation in a variety of business environments, and how the use of favors affects firms’ paths to international expansion. We discuss the concept of favors, and to illustrate the process of favors, we look at culturally rooted examples of their use by managers from the BRIC countries of Brazil, Russia, India, and China. Utilizing neo-institutional theory, we create a typology of four types of environments in which managers and firms from emerging markets conduct business with various relational entities (e.g., governments, customers, suppliers, competitors, alliance partners). We posit that the use of favors by managers compensates for the relatively weak legitimacy of formal institutions in emerging market environments, with favors illustrating the resulting reliance upon informal cultural-cognitive institutions. We develop propositions regarding the impact of the use of favors on the organizational outcomes of growth, legitimacy, and reputation of emerging market firms doing business in each of the four environments. This leads to further propositions regarding how the use of favors can influence their firms’ internationalization growth paths. We conclude that the impact of favors on international growth paths results from the fit or non-fit of their use with the level of legitimacy of the formal institutional environment of the focal relational entity in various business transactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Emerging market economies are coming to be viewed as the world’s economic growth engine in the 21st century as evidenced by their striking recent contribution to world GDP. The terms “emerging market” and “developing country” have been used interchangeably (Doukas & Kan, 2006). The International Finance Corporation (IFC), an arm of the World Bank, coined the term “emerging markets” in the early 1980s, using it to identify its Emerging Markets Database which contains stock market information on firms from these countries (International Finance Corporation, 2006). Within this database, the stock markets of all developing countries are included and thus they are considered to be “emerging markets” (Doukas & Kan, 2006).

In spite of the diversity of countries which can be considered to be developing and thus emerging markets, several management scholars have identified systematic cultural differences between developed and developing countries which have an impact on management practices and firm behavior (e.g., Aycan, 2004; Hoskisson, Eden, Lau, & Wright, 2000; Jaeger, 1990; Jörgensen, Hafsi, & Kiggundu, 1986). Among these differences is the culturally embedded practice of using favors to facilitate business. An early reference to favors noted that in contrast to economic exchange, social exchange “entails unspecified obligations” and that it “involves favors that create diffuse future obligations…and the nature of the return cannot be bargained.” (Blau, 1964: 93). Thus an interaction in the context of a social exchange does not necessarily or does not usually result in an immediate “quid pro quo” between the parties, nor in a very specific one. This characterizes very well the practice of using favors as it occurs in the business environments we are examining.

A few studies have utilized the term “favors” to examine interpersonal interactions within organizations in developed economies (e.g., Flynn, 2003). Most management studies which have addressed favors (e.g., Chen, Friedman, Yu, & Sun, 2011; Flynn, 2003; Ledeneva, 1998; Schuster, 2006), have not provided a specific definition. Drawing in part on the ideas in these studies, we define the practice of giving and receiving favors as “an exchange of outcomes between individuals to accomplish business objectives, typically utilizing one’s connections, that is based on a mutually understood cultural tradition, with reciprocity by the receiver typically not being immediate, and the favor exchange being one which would not be construed as bribery or otherwise illegal within that cultural context” (McCarthy, Puffer, Dunlap, & Jaeger, 2012).

With respect to emerging markets, much recent focus has been on the BRICs—Brazil, Russia, India, and China—which we will use as representatives of emerging markets. According to a Goldman Sachs report, by 2050 the BRIC countries will have the collective potential to surpass the GDP of the original G6 industrialized nations of the United States, Japan, Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy (Wilson & Purushothaman, 2006: 923). To realize such potential, many emerging market (EM) firms, including those in the BRICs, will have to follow paths toward internationalization, with the most successful becoming emerging market multinational enterprises (EMNEs).

With respect to the BRICs, much has been published on the practice of guanxi in China, of which favors are a component (Chen & Chen, 2004; Chen & Chen, 2009; Chen & Tjosvold, 2007; Hitt, Lee, & Yucel, 2002; Luo, 2002), but the guanxi literature has typically not focused on the topic of favors itself (for recent exceptions see Chen et al., 2011; Jiang, Chen, & Shi, 2012). The same could be said about the literature on related practices in Brazil, Russia, and India, known as jeito in Brazil (Amado & Brasil, 1991; Barbosa, 1995), blat/sviazi in Russia (Fitzpatrick, 2000; Ledeneva, 2000; Michailova & Worm, 2003) and jaan-pehchaan in India (Batjargal, 2004; Habib & Zurawicki, 2006; Zhu, Bhat, & Nel, 2005). This article aims to fill this gap by addressing the topic of favors in the context of doing business internationally. A key variable is the strength of the legitimacy of the formal regulative institutional environment, typically being weaker in emerging markets than in developed ones. The importance of formal institutions, such as emerging market governments, in the strategies of companies from such countries has been underemphasized in the literature (Zhou & Peng, 2012). We will argue that such institutional environments lead to a greater use of favors to compensate for that weakness, thereby relying upon an informal, cultural-cognitive institution rather than formal ones.

The concepts and arguments developed in this article focus on how the use of favors by EM managers impacts their organizational outcomes of firm growth, legitimacy, and reputation, as well as how the use of favors can facilitate or inhibit the international expansion of their firms. We begin with a description of favors relevant in both emerging and developed economies and examine their positive and negative aspects in each context. This is followed by further theory development based on institutional theory. We then present our framework for explaining choices that EM managers may make when requesting and/or responding to favors as a pragmatic approach to facilitating the achievement of business objectives. The discussion includes an analysis of the potential impact of favors on an EM firm’s path to internationalization, as well as limitations of the analysis and suggestions for future research.

The culturally embedded practice of favors in emerging markets

The use of favors can have many positive effects on the conduct of business in the often hostile environments of many emerging markets. The key actors relevant to the use of favors by EM managers and firms are what we call their relational entities. We define relational entities as various parties with whom managers may become involved in conducting business, including customers, suppliers, intermediaries, competitors, alliance partners, and government bureaucrats—ranging from top policy makers to lower-level public officials like police, fire, and customs agents. These relational entities can be found in one’s home country, in other emerging markets, or in developed ones.

We see favors as being an informal cultural-cognitive institution (Scott, 2008b) that fills the void created by the weak legitimacy of a country’s formal regulative and normative institutions, as will be explained in the section on institutional theory. The resulting cultural-cognitive schema thus initiates the process of seeking and receiving a favor. It should be noted that favors may, in fact, be used to avoid paying bribes that carry associated costs and potential penalties. In contrast to favors, bribery involves a payment in money or in kind, with the expectation of something in exchange that requires unethical behavior on the part of the recipient of the bribe (Luo, 2002; Rose-Ackerman, 1999, 2002), and is considered illegal as well as unethical in most countries. In fact, Luo (2002) characterized favor exchange in China as a social norm, with bribery being a deviation from the social norm. Nevertheless, such deeply rooted cultural traditions typically coexist with, and can even foster, bribery (Fan, 2002; Tian, 2008), and thus may evoke a perception of pseudo-legitimacy for bribery in such economies. We would argue, however, that EM managers generally view the use of favors as necessary for conducting even day-to-day business with most EM firms and other relational entities with which they conduct business in environments with weak legitimacy of formal regulative institutions.

Favors are also utilized in developed economies, typically within networks. However, although they may facilitate business transactions, favors are generally not essential in those environments since business transactions are typically guided by more transparent, formal, institutionalized practices, and breeches within transactions can be addressed within the legal and regulatory systems. Favors in developed economies are generally used to facilitate business dealings, such as using one’s network to get business leads or to improve the chances of obtaining a contract, but with no guarantee of success. In emerging markets, winning the contract might well be expected by the recipient, as could a reciprocal favor in the future by the giver. The fundamental difference is that the use of favors in most developed countries is far less necessary or frequent, and is not culturally rooted in mainstream business activities, since the rule of law is paramount and is supported by other relatively strong legitimate formal institutions which facilitate doing business.

A short description of culturally specific manifestations of favors in each of the BRIC countries (jeito in Brazil, blat and sviazi in Russia, jaan-pehchaan in India, and guanxi in China) is provided in the Appendix to highlight the cultural-cognitive embeddedness of these practices, each of which emerged in response to specific, and in some cases unique, weaknesses in the formal institutional environment of each country.

Institutional theory

Institutional theory has been recognized as being important for advancing international business theory (Dunning & Lundan, 2008a, b), and contemporary institutional theory is commonly referred to as neo-institutional theory (Scott, 2008a). Institutions are “the humanly devised constraints that structure human interaction” (North, 1990: 3), and have been categorized into three pillars: regulative, normative, and cultural-cognitive (Scott, 1995, 2008b). Regulative refers to formal institutions and related rule systems like laws and regulations as well as state-sanctioned enforcement mechanisms (Scott, 1995). The normative pillar includes institutions like professional societies that specify roles and guidelines for their members. The cultural-cognitive pillar embodies accepted beliefs and values as well as schema for guiding behavior that individuals share through social interaction, and that draw extensively upon a society’s culture (Jepperson, 1991).

Research on emerging markets has also focused on the cultural-cognitive institutional pillar, emphasizing the importance of cultural influences on values and practices of business persons in such settings (Ahlstrom & Bruton, 2006; Batjargal, 2004, 2007a, b; Boisot & Child, 1996; Boisot & Meyer, 2008; Jaeger, 1990; May, Puffer, & McCarthy, 2005; McCarthy & Puffer, 2008; Peng, 2003; Peng & Heath, 1996; Puffer, McCarthy, & Boisot, 2010; Tan, 2002). One study, in fact, has argued that an institution-based view is becoming the “third leg of the strategy ‘tripod’ … as well as a dominant perspective in strategy and IB research on emerging economies…” (Peng, Wang, & Jiang, 2008: 923). Institutional theory helps explain why favors figure so prominently in emerging market countries that are characterized by formal regulative institutions having weak legitimacy, in contrast to the more legitimate formal institutional environments found in most developed countries. Formal institutions typically include entities like governments, regulatory agencies, the judicial system, stock exchanges, rating agencies, and auditing firms.

Drawing from institutional theory, one study has emphasized the important role institutions play in the building of trust in relationships between organizations (Bachmann & Inkpen, 2011). We see such trustbuilding, which can include the reciprocal use of favors, as being more difficult to achieve between organizations with different institutional arrangements. We reach this conclusion based on the concept of institutional distance (Kostova, 1999; Kostova & Roth, 2002), which is “the extent of similarity or dissimilarity between the regulatory, cognitive, and normative institutions of two countries” (Xu & Shenkar, 2002: 608). Thus we view the use of favors as being more common between firms with similar institutional environments because of the typically high institutional distance between emerging and most developed countries, as well as the relatively lower institutional distance between emerging countries. Such a use of favors, we contend, would limit the “liability of foreignness” due to institutional distance which has an impact on the social costs of doing business (Eden & Miller, 2004). Furthermore, multinational enterprises face pressure for isomorphism with their respective overseas environments. These pressures are less for firms which are working with relational entities with whom the institutional distance as well as the liability of foreignness is low, and would include a firm’s need to be perceived as legitimate by relational entities. As Kostova, Roth, and Dacin (2008: 996) have pointed out, “Legitimacy is necessary and critical for organizational survival… (and)… legitimacy is achieved through becoming isomorphic as a result of adopting practices and structures that are institutionalized in a particular environment (field).”

Institutional distance has been shown to be a factor impacting the success of firms expanding overseas, since EM firms, and by implication their managers, have strong political capabilities since they are used to operating in unstable political environments (Guillén & García-Canal, 2009). We view these circumstances as symptoms of the weak legitimacy of formal institutions which necessitates the use of favors, among other behaviors. The same article notes that, as a result, EM firms typically internationalize beyond their home regions first to areas that are culturally, politically, or economically similar, as exemplified in the Uppsala model (Johanson & Vahlne, 2006, 2009).

In institutional theory terms, we will argue that EM firms typically internationalize first to areas that have a low institutional distance from their home environment to achieve organizational outcomes of growth in revenues, market share, and profitability, as well as enhancement of their legitimacy and reputation. We adopt the following definitions of legitimacy and reputation: Legitimacy refers to “actors’ perceptions of the organization, as a judgment with respect to the organization, or as the behavioral consequences of perception and judgment, manifested in actors’ actions—‘acceptance, endorsement, and so forth’ ” (Bitektine, 2011: 152). Reputation refers to “expectations of some behavior or behaviors based on past demonstrations of those same behaviors” (Podolny, 2005).

Consistent with the institutional distance construct, we posit that a firm’s legitimacy and reputation are affected by the use of favors, and will influence potential paths for international expansion. We argue that the practice of favors can sometimes facilitate such expansion, but can be detrimental for EM firms when going beyond other emerging markets to environments where formal institutional legitimacy is stronger. Another way to characterize local environments and their impact on the success of an MNE is to look at institutional distance with respect to the so-called supporting dimensions, which are defined as “…external non-market resources which support the firm’s operations” (Cuervo-Cazurra & Genc, 2011: 449). Developed countries have more advanced supporting dimensions in their business environments (Cuervo-Cazurra & Genc, 2011), which include institutional dimensions such as the rule of law and quality of the judicial system. Those authors also point out that firms from less developed countries will have a relative advantage over firms from more developed countries in a less developed environment as they will have learned how to operate without these supporting resources. We contend that one of the ways in which they do this is through the use of favors.

Of particular importance also is the role of business relationships and networks, which varies throughout the world (Jaeger, 1990; Schuster, 2006; Xin & Pearce, 1996). There is, however, a dearth of research on how national cultures and other institutional pillars affect the formation of personal networks (Brass, Galaskiewicz, Greve, & Wenpin, 2004) and managerial characteristics (Hofstede, 2007). Furthermore, at the societal level, retaining some aspects of culture and tradition in business activities may be more effective than developing comprehensive formal institutions, since the latter involve high fixed infrastructural and institutional costs (Boisot & Child, 1996). Yet, graft and bribery are common where it is accepted practice to rely on other people for help in surmounting bureaucratic barriers, rather than relying on effective and fair systems (Schuster, 2006). One study of the BRICs noted the presence of major corruption, low transparency, and weak corporate governance, as well as their uniformly high rankings in the use of bribery, with Brazil being the lowest of the four, and Russia the highest (Tian, 2008).

EM countries generally have pervasive, entrenched, self-serving, and inefficient bureaucracies whose members have little inclination to surrender power. This situation hinders the development of legitimate formal regulative as well as normative institutions while perpetuating the use of the cultural-cognitive institution of favors to accomplish business goals. Specifically, one study noted that guanxi is a form of connections that serves as a substitute for formal institutional support in environments with weak formal institutions (Xin & Pearce, 1996). Furthermore, a large-scale study of 24 post-communist countries that had failed to develop such legitimate, market-enhancing institutions found that people continued to use individual connections to gain favors, and used bribery when necessary (McMann, 2009).

Institutional theory can thus be a foundation for gaining insights into the role of favors in EM firms’ business activities including their potential international expansion paths. In this context, we will also argue that EM firms and their managers must ultimately adapt to doing business according to the culturally acceptable use of favors in environments with strong formal institutions if they are to successfully complete their journeys of international expansion to those markets. Otherwise their internationalizing journeys risk being cut short and limited to settings with weak institutional environments.

A framework for analyzing EM managers’ use of favors and the impact on their firms’ international expansion

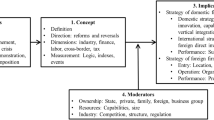

To summarize our concept, we develop a framework depicting EM managers’ propensity to use favors in their dealings with various relational entities (Table 1). We then propose the likely initial international expansion paths of EM firms (Table 2). Drawing from institutional theory, the vertical axis of Table 1 indicates the strength of the legitimacy of the formal institutional environments of those relational entities. The horizontal axis indicates the geographic locus, domestic or international, of the relational entity with which the focal EM manager conducts business. This geographic dimension focuses on the complex culturally based influences affecting the choices that EM managers make with relational entities whose formal institutional environments vary in legitimacy. The differences in both geography and degree of formal institutional legitimacy create situations in which EM managers conduct business in some environments where their relational entities do not share mutually understood cultural traditions, including the use of favors.

The complexities faced by most of these EM managers stem from their propensity to utilize favors in domestic business transactions. We view this practice as being heavily influenced by both their administrative heritage (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989), a phenomenon rooted in cultural traditions, as well as existing relationships and obligations in their social exchanges. Yet, to maximize growth opportunities, establish legitimacy, and secure a positive reputation as they follow a path to full international expansion, EM firm managers will have to adapt to the accepted culturally based use of favors of relational entities in such different institutional environments. In summary, the institutional and geographic dimensions are the basis for the two-by-two matrix in Table 1, which depicts the impact of the use of favors by EM managers on their firms’ growth, legitimacy, and reputation.

The four quadrants of Table 1 depict the types of situations in which EM managers from a single country might operate. We call these managers operating within the four quadrants Traditional Domestic Managers, Progressive Domestic Managers, Traditional International Managers, and Progressive International Managers. We develop propositions for each quadrant about the impact of using favors on company growth, legitimacy, and reputation—three dimensions which we refer to collectively as organizational outcomes. Our framework is based on the view that EM managers are affected by the environments of the relational entities with which they interact. These institutional environments take years to evolve and, in many cases, regardless of the inefficiencies within them, some firms may become “locked-into” partnering relationships with firms from similar backgrounds (Narula, 2002). Thus, when interacting with relational entities whose formal institutions have weak legitimacy, as is typical in most emerging markets, we argue that most EM managers necessarily rely on favors, a practice with which both parties are familiar.

A second important topic for international business is the potential international expansion paths of EM firms. Internationalization research has focused mostly on the stage model behaviors of first-mover entrants from developed market economies, with far less attention paid to the internationalization strategies of latecomers from emerging market economies (Ricart, Enright, Ghemawat, Hart, & Khanna, 2004). More recently, however, some research has focused on emerging market multinationals (EMNEs), examining how these firms internationalize (e.g., Guillén & García-Canal, 2009; Ramamurti & Singh, 2009). Furthermore, various environmental factors in less developed countries can, in some environments, give EMNEs a competitive advantage over developed country MNEs (Cuervo-Cazurra & Genc, 2008; 2011).

Building on this foundation, we argue that continual adjustments must be made to traditional internationalization theories to explain how managers of successful EM firms (such as Brazil’s Embraer, Russia’s Severstal, India’s Tata, and China’s Lenovo) have been able to compete successfully against developed market competitors. Thus we examine how the familiarity, as well as the complexity, of relationships developed through informal institutional settings, specifically the relational capital associated with social networks (Narula & Santangelo, 2009), including the use of favors, can help or hinder the international expansion patterns of EMNEs. Using the same two axes as Table 1, Table 2 depicts the most likely international expansion paths of EM firms, which we posit are influenced by their managers’ propensities to use favors.

Table 2 depicts propositions regarding the most likely international expansion paths for EM firms doing business in each of the four environments. We regard these expansion paths of EM firms as being influenced by the legitimacy of the formal institutions of the relational entity’s country, domestic or international. In line with the Uppsala model mentioned earlier, we would argue that EM firms typically internationalize beyond their home regions first to areas that are similar to the business environment in which they operate (Johanson & Vahlne, 2006, 2009). We refer to the EM firms represented in Table 2 as Traditional Domestic Firms, Progressive Domestic Firms, Traditional Internationalizer Firms, and Progressive Internationalizer Firms. A firm is positioned in the matrix according to the most internationalized quadrant in which it does a significant amount of its business. This does not necessarily mean that it constitutes the majority of its business, but that it is a large enough segment to have an important impact on the firm’s revenues and profitability. The propositions regarding the most likely international expansion paths are represented by the horizontal arrows where there would be movement between quadrants.

We see institutional theory as providing a useful way of understanding how the overall practice of granting and receiving favors influences the location-specific choices of EM firms. Culture and related managerial practices have been suggested as having a major impact on a firm’s ability to balance domestic and international pressures. Such practices are often a reflection of the role played by locally embedded institutions and policy responses (Buckley & Ghauri, 2004; Hofstede, 2007). Consequently, the aspect of institutional theory relevant to our analysis is the degree of legitimacy of the formal institutional environment of the EM firm’s focal relational entity. We also posit that formal institutions in domestic or international settings can have an impact on the path of an EM firm’s internationalization.

Weaker formal institutional environments can result in a competitive advantage for an EMNE over a developed country MNE (Cuervo-Cazurra & Genc, 2008, 2011). Yet, these types of tacit and complex social networking exchanges where members understand the tacit “rules” of the network can cause managers to become short-sighted. This could lead them to overly focus on these location-bounded assets at the expense of partnering with other firms having potentially greater asset profiles (Narula & Santangelo, 2009), knowledge, capabilities, and access to global resources such as are typically found in more developed countries. We recognize the relatively lower social cost in partnering with entities having similar institutional settings; that is, a relatively low institutional distance (Eden & Miller, 2004), and where firms have built up relational capital (Narula & Santangelo, 2009). However we argue that when dealing with relational entities from environments with strong, legitimate formal institutions, EM managers would need to adapt their use of favors and be guided by internationally accepted standards adhered to by those relational entities; that is, adapt to the local environment’s rule and belief systems in order to survive (Vora & Kostova, 2007).

An additional complexity is the case where EM managers deal simultaneously with relational entities whose formal institutional environments have different degrees of legitimacy. In such cases, EM managers might use favors with some, but not with others. For instance, Hadjikhani, Lee, and Ghauri (2007) found that managers are likely to engage in a variety of heterogeneous behaviors when interacting and/or expanding their business markets within uniquely different social-political (i.e., institutional) environments. Further, they suggested that additional research is needed to develop a better understanding of the types of strategies that firms use when they internationalize into different rather than similar socio-political environments. Consistent with this view, we seek to provide a richer understanding of how managers deal with different socio-political environments to achieve business goals through the use or non-use of favors.

Proposition development

The following propositions examine the impact of managers’ use of favors with various relational entities on three organizational outcomes—growth, legitimacy, and reputation. The underlying rationale is that firms whose managers’ use of favors matches the legitimacy level of their relational entity’s formal institutional environment will have better organizational outcomes than firms whose use of favors is mismatched, an argument mirroring that of Cuervo-Cazurra and Genc (2011).

For Traditional Firm managers, for instance, the use of favors to compensate for the weak formal institutional environment shared with the domestic relational entity should enhance organizational outcomes. Conversely, the use or attempted use of favors by Progressive Firm managers with relational entities having strong formal institutional environments to try to bypass institutional regulations can hamper performance, as favors will likely be viewed as inappropriate. In terms of institutional distance, the smaller that distance is between the firm’s environment and that of its relational entity, the better the firm’s organizational outcomes will be regarding the use of favors with that relational entity, all other things being equal. Again this is in line with arguments made by Cuervo-Cazurra and Genc (2011). Additionally, the use of favors by Progressive Firm managers in weak formal institutional environments could lead to poor organizational outcomes, particularly with respect to reputation and legitimacy in their home environment. This would also be true, to a lesser extent, for Traditional Firm managers who aspire to operate in developed markets, since a tarnished reputation and low legitimacy could result in inhibiting their ability to expand in those markets. We will examine more closely each type of firms’ managers in Table 1, and present propositions linking their use of favors to organizational outcomes. In essence, two fundamental underlying propositions are inherent in our argument. However, to specify how traditional and progressive EM managers operate in both domestic and international markets, we expand these into four propositions (1a, 2a, 3a, 4a) and develop four additional propositions (1b, 2b, 3b, 4b) as the most likely initial international expansion paths of firms in each quadrant.

Traditional Domestic managers and firms

Traditional Domestic refers to EM managers and firms having relational entities located and operating primarily in their home country in sectors where formal institutions have weak legitimacy. Such EM managers and firms create routines that help them operate in these environments, and can be seen as resources that they bring to similar environments that may give them a competitive advantage with respect to firms from developed countries (Cuervo-Cazurra & Genc, 2008). With local connectivity, EM managers and firms are likely to have established complex socio-political relationships, through both formal and informal institutional activities which have been built up over time (Narula, 2002). According to Hadjikhani et al. (2007: 920), “in this environment, the relationships are explained to be embedded in a network in which the actors directly and indirectly are interdependent on each other.” Being a member of such a network can yield a high degree of location-specific assets such as the familiarity gained through interacting with a local supplier, customer, or government official, as well as deep understanding of the local knowledge infrastructure. Such familiarity, however, can create inertia for firms wanting to do business beyond their local environment (Narula, 2002; Narula & Santangelo, 2009). By depending upon local familiarity, cultural and administrative distance is created with more economically developed environments. Such distances encompass institutional distance, but in our view go beyond it, and can create additional barriers to global integration (Ghemawat, 2001).

Thus, we argue that Traditional Domestic managers are likely to utilize favors to compensate for the void created by the weak legitimacy of the formal institutional environment that they share with their relational entities. However, the use of favors will inhibit their firms’ ability to internationalize beyond countries with a similar propensity to use favors. Thus, such managers will more likely be attracted to institutional environments similar to their own where they have a higher probability of success. This leads to the following propositions:

Proposition 1a

The more that managers of Traditional Domestic firms use favors with other Traditional Domestics, the more growth their firms will experience in that market, without lessening their firms’ legitimacy or reputation. Yet, doing so may lessen their growth opportunities, legitimacy, and reputation with relational entities whose formal institutional environments have strong legitimacy.

Proposition 1b

The most likely initial international expansion path for Traditional Domestic firms is to do business with relational entities in the Traditional Internationalizer quadrant where favors are also commonly used because of the weak legitimacy of formal institutions.

Progressive Domestic managers and firms

Progressive Domestic refers to EM managers and firms that conduct business with relational entities in domestic industry segments characterized by formal regulative institutions exhibiting relatively strong legitimacy. In cases where governments and regulators have strengthened legal and regulative mechanisms affecting industries such as pharmaceuticals and financial services, more transparency is expected by various stakeholders, in contrast to other more traditional local sectors like retail trade or manufacturing. In the former sectors, we posit that managers of Progressive Domestic firms are exposed to more internationally accepted industry practices and managerial mindsets. This exposure is likely to influence their behavior and decision making, and as such, we propose that Progressive Domestic managers are unlikely to depend upon favors in spite of their traditional cultural acceptance in the home country. Therefore, the more that favors are used, the greater is the potential negative impact on their reputation, which in turn will have a spillover effect on legitimacy and growth, resulting in poorer outcomes for these Progressive Domestic firms. This will be especially true with respect to dealings with Progressive Internationalizers.

When such firms increase their knowledge of internationally accepted industry practices, they are less likely to be overly dependent upon localized social networks to gain competitive advantage over rivals (e.g., Narula, 2002; Narula & Santangelo, 2009). Thus, as Progressive Domestic firms gain firm-specific assets beyond the typical country-specific assets of their home market environments, these valuable experiences can lead to positive organizational outcomes with Progressive Domestics and Progressive Internationalizers. However, such actions could also lead to less growth in the two Traditional quadrants where the formal institutional environment is weak and the use favors is more critical to success. This leads to the following propositions:

Proposition 2a

The more that managers of Progressive Domestic firms use favors, the less will be their firms’ growth opportunities, legitimacy, and reputation, except with relational entities whose formal institutional environments have weak legitimacy.

Proposition 2b

The most likely initial international expansion path for Progressive Domestic firms is to do business with relational entities in the Progressive Internationalizer quadrant where favors are not commonly used because of the strong legitimacy of formal institutions.

Traditional Internationalizer managers and firms

Traditional Internationalizer refers to EM managers and firms that conduct business with relational entities in other emerging markets whose formal institutions have weak legitimacy. These managers are likely to utilize favors since their behavior is driven by routines inherent in their past experience and the mutual understanding that favors are an institutionalized social norm of doing business. As such, their organizational outcomes may be positive, and they may have a competitive advantage over firms from environments with stronger institutional legitimacy (Cuervo-Cazurra & Genc, 2008). Conversely, organizational outcomes are likely to be poorer in quadrants with strong formal institutional environments, where favors would likely be a competitive disadvantage. The more that Traditional Internationalizers use favors, the greater is the potential negative impact on their reputation, which will have a spillover effect on legitimacy and growth, resulting in poorer performance outcomes.

We also recognize that a relative weakness of formal institutions in the home environment can act as a barrier to firms wanting to internationalize to environments with stronger institutions. Tensions have long been associated with growing a firm’s business globally to take advantage of future economies of scale, while at the same time still meeting the demands of local consumers (Buckley & Ghauri, 2004). In essence, to become Progressive Internationalizers, these firms must adapt their use of favors, even within the highly established socio-political relationships upon which they have become dependent, since a misuse of favors can lead to reduced legitimacy and reputation. The use of favors by Traditional Internationalizers will inhibit their firms’ ability to internationalize beyond countries with a similar propensity to use favors, and they will more likely continue to be attracted to institutional environments similar to their own where they have a higher probability of success. This leads to the following propositions:

Proposition 3a

The more that managers of Traditional Internationalizer firms use favors in other emerging markets, the more growth their firms will experience in those markets without lessening their firms’ legitimacy or reputation. Yet, doing so will lessen their growth opportunities, legitimacy, and reputation with relational entities whose formal institutional environments have strong legitimacy.

Proposition 3b

The most likely initial international expansion path for Traditional Internationalizer firms is to develop business with relational entities from countries in the same quadrant, where favors are also commonly used because of the weak legitimacy of formal institutions.

Progressive Internationalizer managers and firms

Progressive Internationalizer refers to EM managers and firms that interact with relational entities whose country’s formal institutions are strong, such as developed economies like the US, Canada, Australia/New Zealand, and Western European countries, as well as some Progressive Domestic and Progressive Internationalizer firms from emerging markets.

Progressive Internationalizer firms tend to source-in unique firm capabilities from more advanced economies, rather than just exploiting their unique local consumer niches on a global scale. Firms attempting to enter developed markets typically encounter substantial challenges (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 2000), and developed market experience for EM firms has typically been found to begin when developed economy firms seek to enter an emerging market’s local environment through strategic alliances. Thomas, Eden, Hitt, and Miller (2007) found that such alliance partnerships can not only facilitate EM firm survival, but also the entry of those firms into developed markets. As newly established Progressive Internationalizers gain experience in those markets, they are unlikely to utilize favors in their customary way, being guided instead by international standards for conducting business. In our view, a primary motivation is to demonstrate that they are trustworthy and dependable. In essence, these firms seek to achieve the growth, legitimacy, and reputational opportunities that can come from being a Progressive Internationalizer. With respect to the use of favors, they behave in a manner similar to that of firms from developed economies. This leads to the following propositions:

Proposition 4a

The more that managers of Progressive Internationalizer firms use favors, the less will be their firms’ growth opportunities, legitimacy, and reputation, except with relational entities whose formal institutional environments have weak legitimacy.

Proposition 4b

The most likely initial international expansion path for Progressive Internationalizer firms is to develop business with relational entities in the same quadrant. This includes both developed country firms and Progressive Internationalizer firms from other countries that have operated in sectors where favors are not commonly used because of the strong legitimacy of formal institutions.

Discussion, limitations, and future research

This article contributes to calls for greater theory development on EM firms (Bruton & Lau, 2008) and their international expansion by examining the impact of EM managers’ use of favors on their firms’ growth, reputation, and legitimacy, as related to their firms’ international expansion paths. We created a two-dimensional framework and developed propositions to explore these relationships, and emphasized how the use of favors can facilitate or inhibit that expansion to becoming an EMNE. Brief examples of the nature of favors in the BRICs, provided in the Appendix, illustrate the deeply culturally, and indeed institutionally, rooted nature of this phenomenon of social exchange.

Discussion

We have argued that the use of favors by some EM managers, specifically Traditional Domestics, can facilitate international expansion to other emerging markets with similar cultural-cognitive informal institutions (i.e., relatively low institutional distance). As a consequence, such practices may give them a competitive advantage (Cuervo-Cazurra & Genc, 2008). However, using favors could inhibit expansion beyond those institutionally compatible countries, and thus be a barrier to internationalizing to most developed countries. In contrast, the use of favors by Progressive Domestics would likely inhibit international expansion, even to other emerging markets, since Progressive Domestics’ legitimacy and reputation would be harmed by relying on that practice.

We have also taken a more nuanced view of isomorphism and its connection to organizational outcomes. Institutional theorists (Kostova et al., 2008; Vora & Kostova, 2007) assert that institutional theory suggests that organizations must adapt to the local environment’s rule and belief systems in order to survive. We have argued, in the context of using favors, that this is true for Traditional firms. However, it would not necessarily apply to Progressive firms whose use of favors, even in a traditional market where favors are common, would harm their overall legitimacy and reputation in progressive markets, making survival and growth in those markets more difficult. Thus, firms from emerging markets with international ambitions must pay attention to more than one environment and must keep in mind the impact of their use of favors on multiple stakeholders in multiple environments. It is unlikely that they could be isomorphic to two environments with conflicting demands. However, this view might be mitigated by the argument that where institutional logics compete, coexistence can be maintained and managed through the development of collaborative relationships (Reay & Hinings, 2009).

Our analysis has practical implications for managers and firms from developed economies in that they should recognize that EM managers may utilize favors differently depending on the relational entities with whom they are dealing. For instance, Progressive Internationalizers will have the most experience dealing with entities which adhere to internationally accepted standards, and thus might be the most suitable emerging market partners for developed market firms. Also, Progressive Domestics are likely to seek international legitimacy and thus avoid the use of favors, seeing their internationalization expansion path as doing business with entities whose formal institutional environments are strong. Similarly, Traditional Internationalizers might, over time, adapt their use of favors as they expand to environments where formal institutional environments have strong legitimacy. Consequently, those two types of EM firms might also have the potential to be good partners, while Traditional Domestics that rely extensively on favors would make the least suitable partners. Finally, developed country managers must avoid the tendency toward isomorphism when operating in emerging markets, and maintain their internationally based standards with regard to favors.

Limitations

Several limitations in this research must be acknowledged. First, our definition of the use of favors creates boundaries about how to interpret the practice of favors in business relationships. We have asserted, for instance, that givers and receivers expect that a favor will be reciprocated at an undetermined future date, as is suggested by social exchange theorists like Blau (1964). Nevertheless, there may be situations in which this assumption of reciprocity does not apply, such as in cases where the giver of the favor has more resources than the recipient and does not desire or expect reciprocation. This is often true for guanxi in China, such as when senior and junior members of a relationship have unequal rights and obligations (Chen & Chen, 2004). Such an understanding of inherent reciprocity can be viewed as what Cropanzano and Mitchell (2005) have termed a “folk belief.” We see this as a situation where favors would be put into a “common pot” and retrieved when needed. The same can be said for the Brazilian jeito where there is often no relationship between the giver and the receiver of the favor, and there is a “diffuse sense of reciprocity” between the two (Barbosa, 1995). Such situations could be investigated further in future research.

Second, we made the assumption that favors are employed uniformly in emerging market countries, and less so in developed economies. However, we recognize that the use of favors can vary from country to country, and may exist on more of a continuum rather than having discreet demarcations as is implied in our discussion. What we are addressing is the relative prevalence of the use of favors in the “home” environment versus that of the environment of the relational entity. We consider our comparison to be similar to that made by Cuervo-Cazurra and Genc (2011) when assessing the relative competitive advantages of firms in a specific environment by looking at their relative distances from that environment.

Third, our propositions regarding the impact of the use of favors on EM firms’ growth, legitimacy, and reputation are stated categorically within the four quadrants, but we recognize that in reality these too likely exist on a continuum. Nevertheless, our intent was to draw clear distinctions among EM managerial behaviors and firms’ initial international expansion paths to emphasize the major differences that exist among those four quadrants. A fourth limitation is that we have focused only on the most likely initial internationalization paths, but realize that other initial or sequential expansion paths are also feasible from most quadrants. Finally, this article has focused on EM managers and firms, yet our framework might also be applied to developed market managers and firms.

Future research

Institutional theory is only one lens through which to study the use of favors. Social exchange theory could also be an appropriate foundation for such research. Social exchange theorists have noted that the exchange occurs within the context of a relationship and is seen as involving a series of interactions that generate some form of obligations (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Emerson, 1976) which are usually seen as interdependent and contingent on the actions of another person (Blau, 1964; Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). Social exchange theory also addresses the nature of the rules of reciprocity, and these rules (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005) might be applied to the use of favors.

Another approach might be utilizing psychic distance, which has similarities to institutional distance, but psychic distance encompasses other characteristics beyond institutions. Child, Rodrigues, and Frynas (2009: 201) define psychic distance as “the distance that is perceived to exist between characteristics of a firm’s home country and a foreign country with which that firm is, or is contemplating, doing business or investing.” Our theoretical framework would suggest that EM managers and firms would adapt their use of favors in order to reduce the psychic distance between them and firms adhering to international business standards. However, some EM firms may be resistant to move beyond their comfort zones and may be unwilling to internationalize into markets that are more psychically or culturally distant (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977, 2006).

The practice of using favors can also be viewed in the context of country-specific assets and firm-specific assets (Rugman, 1987; Rugman & Verbeke, 2003). As has been pointed out by Cuervo-Cazurra and Genc (2008), experience and ability in the of use favors can be considered a country-specific competitive advantage for EM firms in their local environments, or when dealing with most firms from other emerging markets that share a common understanding and acceptance of using favors to achieve business goals. For firms that decide to internationalize beyond familiar environments and do business with entities in or from developed economies, research could examine the process by which such firms adapt their use of favors and comply with internationally accepted business practices, thereby acquiring different firm-specific assets. Some ways of developing such assets might include listing on a developed economy’s stock exchange or establishing headquarters there, both of which can bring the increased legitimacy and reputation associated with such institutional offshoring (Boisot & Meyer, 2008). Additionally, hiring executives from developed economies, as well as engaging in joint ventures with firms from those economies, can enhance learning and bring relevant knowledge to such EM firms.

Research results on the use of favors by EM managers and firms might also be contrasted to, and potentially integrated with, traditional internationalization strategies that were created for developed economy firms, such as the international product life cycle (McGregor, 1993), international strategy (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989, 2000), and the eclectic paradigm (Dunning, 1980, 1988, 2001).

Conclusion

In conclusion, further research on the use of favors, and the inherent use of networks among EM managers and firms, could be approached from various theoretical perspectives. We have examined the use of favors and its role in overcoming institutional weakness, its impact on competitive advantage in weak and strong institutional environments, the influence it might have on the choice of overseas partners, and its impact on international expansion paths. This leads to a better understanding of the importance of favors to managers of emerging market firms doing business in both emerging and developed markets, and of their firms’ internationalization expansion paths. Both insights can contribute to a broader understanding of international business and the evolution of emerging market multinationals.

References

Ahlstrom, D., & Bruton, G. D. 2006. Venture capital in emerging economies: Networks and institutional change. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30: 299–320.

Amado, G., & Brasil, H. V. 1991. Organizational behaviors and cultural context: The Brazilian “jeitinho”. International Studies of Management & Organization, 21: 38–61.

Aycan, Z. 2004. Leadership and teamwork in the developing country context. In H. W. Lane, M. Maznevski, M. E. Mendenhall & J. McNett (Eds.). The Blackwell handbook of global management: A guide to managing complexity: 406–422. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Bachmann, R., & Inkpen, A. C. 2011. Understanding institutional-based trust building processes in inter-organizational relationships. Organization Studies, 32: 281–301.

Barbosa, L. N. d. H. 1995. The Brazilian jeitinho: An exercise in national identity. In D. J. Hess & R. A. Da Matta (Eds.). The Brazilian puzzle: Culture on the borderlands of the western world: 35–48. New York: Columbia University Press.

Bartlett, C. A., & Ghoshal, S. 1989. Managing across borders. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Bartlett, C. A., & Ghoshal, S. 2000. Going global: Lessons from late movers. Harvard Business Review, 78: 132–142.

Batjargal, B. 2004. Software entrepreneurship: Knowledge networks and performance of software ventures in emerging economies. Ann Arbor: Davidson Institute, University of Michigan Business School.

Batjargal, B. 2007a. Comparative social capital: Networks of entrepreneurs and venture capitalists in China and Russia. Management and Organization Review, 3: 397–419.

Batjargal, B. 2007b. Network triads: Transitivity, referral and venture capital decisions in China and Russia. Journal of International Business Studies, 38: 998–1012.

Bhandwale, A. A. 2004. Freelang Hindi-English dictionary. Bangkok: Beaumont.

Bitektine, A. 2011. Toward a theory of social judgments of organizations: The case of legitimacy, reputation, and status. Academy of Management Review, 36: 151–179.

Blau, P. M. 1964. Exchange and power in social life. New York: Wiley.

Boisot, M., & Child, J. 1996. From fiefs to clans and network capitalism: Explaining China’s emerging economic order. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41: 600–628.

Boisot, M., & Meyer, M. W. 2008. Which way through the open door? Reflections on the internationalization of Chinese firms. Management and Organization Review, 4: 349–365.

Brass, D. J., Galaskiewicz, J., Greve, H. R., & Wenpin, T. 2004. Taking stock of networks and organizations: A multilevel perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 47: 795–817.

Bruton, G. D., & Lau, C.-M. 2008. Asian management research: Status today and future outlook. Journal of Management Studies, 45: 636–659.

Buckley, P., & Ghauri, P. 2004. Globalisation, economic geography and the strategy of multinational enterprises. Journal of International Business Studies, 35: 81–98.

Chen, C., & Chen, X.-P. 2009. Negative externalities of close guanxi within organizations. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 26(1): 37–53.

Chen, N., & Tjosvold, D. 2007. Guanxi and leader member relationships between American managers and Chinese employees: Open-minded dialogue as mediator. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 24(2): 171–189.

Chen, X.-P., & Chen, C. C. 2004. On the intricacies of the Chinese guanxi: A process model of guanxi development. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 21(3): 305–324.

Chen, Y., Friedman, R., Yu, E., & Sun, F. 2011. Examining the positive and negative effects of guanxi practices: A multi-level analysis of guanxi practices and procedural justice perceptions. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 28(4): 715–735.

Child, J., Rodrigues, S., & Frynas, J. 2009. Psychic distance, its impact and coping modes interpretations of sme decision makers. Management International Review, 49: 199–224.

Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. 2005. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31: 874–900.

Cuervo-Cazurra, A., & Genc, M. 2008. Transforming disadvantages into advantages: Developing-country mnes in the least developed countries. Journal of International Business Studies, 39: 957–979.

Cuervo-Cazurra, A., & Genc, M. E. 2011. Obligating, pressuring, and supporting dimensions of the environment and the non market advantages of developing country multinational companies. Journal of Management Studies, 48: 441–455.

Doukas, J. A., & Kan, O. B. 2006. Does global diversification destroy firm value?. Journal of International Business Studies, 37: 352–371.

Dunfee, T. W., & Warren, D. E. 2001. Is guanxi ethical? A normative analysis of doing business in China. Journal of Business Ethics, 32: 191–204.

Dunning, J. H. 1980. Toward an eclectic theory of international production: Some empirical tests. Journal of International Business Studies, 11: 9–31.

Dunning, J. H. 1988. The eclectic paradigm of international production: A restatement and some possible extensions. Journal of International Business Studies, 19: 1–31.

Dunning, J. H. 2001. The eclectic (oli) paradigm of international production: Past, present and future. International Journal of the Economics of Business, 8: 173–190.

Dunning, J. H., & Lundan, S. M. 2008a. Institutions and the oli paradigm of the multinational enterprise. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 25(4): 573–593.

Dunning, J. H., & Lundan, S. M. 2008b. Multinational enterprises and the global economy. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Eden, L., & Miller, S. R. 2004. Distance matters: Liability of foreignness, institutional distance and ownership strategy. Advances in International Management, 16: 187–221.

Efremova, T. 2000. Novyi slovar’ russkogo yazyka, tolkovo-slovoobrazitel’nyi, Vol. 2. Moscow: Russkii Yazyk Press.

Emerson, R. 1976. Social exchange theory. Annual Review of Sociology: 335–362.

Fan, Y. 2002. Guanxi’s consequences: Personal gains at social cost. Journal of Business Ethics, 38: 371–380.

Fitzpatrick, S. 2000. Blat in Stalin’s time. In S. Lovell, A. Ledeneva & A. Rogachevskii (Eds.). Bribery and blat in Russia: 166–182. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Flynn, F. J. 2003. How much should I give and how often? The effects of generosity and frequency of favor exchange on social status and productivity. Academy of Management Journal, 46: 539–553.

Ghemawat, P. 2001. Distance still matters. The hard reality of global expansion. Harvard Business Review, 79: 137–147.

Guillén, M., & García-Canal, E. 2009. The American model of the multinational firm and the ‘new’ multinationals from emerging economies. Academy of Management Perspectives, 23: 23–35.

Habib, M., & Zurawicki, L. 2006. Corruption in large developing economies: The case of Brazil, Russia, India and China. In S. Jain (Ed.). Emerging economies and the transformation of international Business: Brazil, Russia, India and China (BRICs): 452–477. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Hadjikhani, A., Lee, J., & Ghauri, P. 2007. Network view of MNCs’ socio-political behavior. Journal of Business Research, 61: 921–924.

Hitt, M. A., Lee, H.-U., & Yucel, E. 2002. The importance of social capital to the management of multinational enterprises: Relational networks among Asian and Western firms. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 19(2–3): 353–372.

Hofstede, G. 2007. Asian management in the 21st century. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 24(4): 411–420.

Hoskisson, R., Eden, L., Lau, C., & Wright, M. 2000. Strategy in emerging economies. Academy of Management Journal, 43: 249–267.

International Finance Corporation. 2006. Where is the smart money going and why. http://www.ifc.org/IFCExt/pressroom/IFCPressRoom.nsf/0/DE27141B248033878525717100472AA7?OpenDocument, Accessed Sept. 23, 2011.

Jaeger, A. 1990. The applicability of western management techniques in developing countries: A cultural perspective. In A. Jaeger & R. Kanungo (Eds.). Management in developing countries: 131–145. London: Routledge.

Jepperson, R. 1991. Institutions, institutional effects, and institutionalism. In W. W. Powell & P. J. DiMaggio (Eds.). The new institutionalism in organizational analysis: 143–163. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Jiang, X., Chen, C. C., & Shi, K. 2012. Favor in exchange for trust? The role of subordinates’ attribution of supervisory favors. Asia Pacific Journal of Management. doi:10.1007/s10490-011-9256-6.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J.-E. 1977. The internationalization process of the firm: A model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitment. Journal of International Business Studies, 8: 23–32.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J.-E. 2006. Commitment and opportunity development in the internationalization process: A note on the Uppsala internationalization process model. Management International Review, 46: 165–178.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J. E. 2009. The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. Journal of International Business Studies, 40: 1411–1431.

Jörgensen, J., Hafsi, T., & Kiggundu, M. 1986. Towards a market imperfections theory of organizational structure in developing countries. Journal of Management Studies, 23: 417–442.

Kostova, T. 1999. Transnational transfer of strategic organizational practices: A contextual perspective. Academy of Management Review: 308–324.

Kostova, T., & Roth, K. 2002. Adoption of an organizational practice by subsidiaries of multinational corporations: Institutional and relational effects. Academy of Management Journal, 45: 215–233.

Kostova, T., Roth, K., & Dacin, M. T. 2008. Note: Institutional theory in the study of multinational corporations: A critique and new directions. Academy of Management Review, 33: 994–1006.

Ledeneva, A. V. 1998. Russia’s economy of favours: Blat, networking and informal exchange. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ledeneva, A. V. 2000. Blat practices in Soviet and post-Soviet Russia. In S. Lovell, A. Ledeneva, & A. Rogachevskii (Eds.). Bribery and blat in Russia: 1–19. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Luo, Y. 2000. Guanxi and business. Hackensack, NJ: World Scientific.

Luo, Y. 2002. Corruption and organization in Asian management systems. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 19(2–3): 405–422.

May, R. C., Puffer, S. M., & McCarthy, D. J. 2005. Transferring management knowledge to Russia: A culturally based approach. Academy of Management Executive, 19: 24–35.

McCarthy, D. J., & Puffer, S. M. 2008. Interpreting the ethicality of corporate governance decisions in Russia: Utilizing integrative social contracts theory to evaluate the relevance of agency theory norms. Academy of Management Review, 33: 11–31.

McCarthy, D. J., Puffer, S. M., Dunlap, D., & Jaeger, A. M. 2012. A stakeholder approach to the ethicality of BRIC-firm managers’ use of favors. Journal of Business Ethics. Forthcoming.

McGregor, R. S. 1993. The Oxford Hindi-English dictionary. New York: Oxford University Press.

McMann, K. M. 2009. Market reform as a stimulus to particularistic politics. Comparative Political Studies, 42: 971–994.

Michailova, S., & Worm, V. 2003. Personal networking in Russia and China: Blat and guanxi. European Management Journal, 21: 509.

Mohanan, T. 1994. Argument structure in Hindi. Stanford: Center for the Study of Language and Information (CSLI Publications).

Narula, R. 2002. Innovation systems and ‘inertia’ in R&D location: Norwegian firms and the role of systemic lock-in. Research Policy, 31: 795–816.

Narula, R., & Santangelo, G. 2009. Location, collocation and R&D alliances in the European ICT industry. Research Policy, 38: 393–403.

North, D. C. 1990. Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Peng, M. W. 2003. Institutional transitions and strategic choices. Academy of Management Review, 28: 275–296.

Peng, M. W., & Heath, P. S. 1996. The growth of the firm in planned economies in transition: Institutions, organizations, and strategic choice. Academy of Management Review, 21: 492–528.

Peng, M. W., Wang, D. Y. L., & Jiang, Y. 2008. An institution-based view of international business strategy: A focus on emerging economies. Journal of International Business Studies, 39: 920–936.

Podolny, J. M. 2005. Status signals: A sociological study of market competition. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Puffer, S. M., McCarthy, D. J., & Boisot, M. 2010. Entrepreneurship in Russia and China: The impact of formal institutional voids. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34: 441–467.

Ramamurti, R., & Singh, J. V. 2009. Emerging multinationals in emerging markets. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Reay, T., & Hinings, C. 2009. Managing the rivalry of competing institutional logics. Organization Studies, 30: 629–652.

Ricart, E., Enright, M., Ghemawat, P., Hart, S., & Khanna, T. 2004. New frontiers in international strategy. Journal of International Business Studies, 35: 175–201.

Rose-Ackerman, S. 1999. A grand corruption and the ethics of global business. Working Paper, Yale School of Management’s Legal Scholarship Network, New Haven, CT.

Rose-Ackerman, S. 2002. “Grand” corruption and the ethics of global business. Journal of Banking & Finance, 26: 1889–1918.

Rugman, A. 1987. The firm-specific advantages of Canadian multinationals. Journal of International Economic Studies: 1–14.

Rugman, A. M., & Verbeke, A. 2003. Extending the theory of the multinational enterprise: Internalization and strategic management perspectives. Journal of International Business Studies, 34: 125–137.

Schuster, C. P. 2006. Negotiating in BRICs: Business as usual isn’t. In S. Jain (Ed.). Emerging economies and the transformation of international business: Brazil, Russia, India and China (BRICs): 410–427. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Scott, W. R. 1995. Institutions and organizations: Ideas and interests. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Scott, W. R. 2008a. Approaching adulthood: The maturing of institutional theory. Theory and Society, 37: 427–442.

Scott, W. R. 2008b. Institutions and organizations: Ideas and interests. Los Angeles: Sage.

Tan, J. 2002. Culture, nation, and entrepreneurial strategic orientations: Implications for an emerging economy. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26: 95–111.

Thomas, D. E., Eden, L., Hitt, M. A., & Miller, S. R. 2007. Experience of emerging market firms: The role of cognitive bias in developed market entry and survival. Management International Review, 47: 845–867.

Tian, Q. 2008. Perception of business bribery in China: The impact of moral philosophy. Journal of Business Ethics, 80: 437–445.

Vora, D., & Kostova, T. 2007. A model of dual organizational identification in the context of the multinational enterprise. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 28: 327–350.

Wilson, D., & Purushothaman, R. 2006. Dreaming with BRICs: The path to 2050. In S. Jain (Ed.). Emerging economies and the transformation of international business: Brazil, Russia, India and China (BRICs): 3–45. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Xin, K. R., & Pearce, J. L. 1996. Guanxi: Connections as substitutes for formal institutional support. Academy of Management Journal, 39: 1641–1658.

Xu, D., & Shenkar, O. 2002. Institutional distance and the multinational enterprise. Academy of Management Review, 27: 608–618.

Yakubovich, V. 2005. Weak ties, information, and influence: How workers find jobs in a local Russian labor market. American Sociological Review, 70: 408–421.

Zhou, J. Q., & Peng, M. W. 2012. Does bribery help or hurt firm growth around the world? Asia Pacific Journal of Management. doi:10.1007/s10490-011-9274-4.

Zhu, Y., Bhat, R., & Nel, P. 2005. Building business relationships: A preliminary study of business executives’ views. Cross Cultural Management, 12: 63–84.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix

Culturally based favors in the BRICs

Brazil: The use of jeito

One of the distinguishing features of Brazilian culture is the notion of “jeito” or “jeitinho” (diminutive of jeito). It has been described as “… a particular way in which Brazilians are able to bend rules in their favour and overcome major obstacles. Jeitinho has been celebrated by many as flexibility in doing business and organizing. However, if stretched too far, jeitinho can raise serious legal and ethical issues in which foreign companies prefer not to get involved (Rodrigues & Barros, 2002)” (as cited in Child et al., 2009: 212). Although the jeitinho is typically Brazilian, it is also a confirmation of the “personalist” and “social” dimension of this Latin American culture, and is rooted in the colonial history of Brazil (Amado & Brasil, 1991). The jeito arose in reaction to the very formal and rigid government bureaucracy, a legacy of the Portuguese colonial administration, which exists to this day. It also fits with the relationship-oriented nature of Brazilian as well as other Latin cultures (Schuster, 2006).

Russia: The use of blat or sviazi

Blat has been defined as “the Russian term for an unofficial system of exchange of goods and services based on principles of reciprocity and sociability” (Fitzpatrick, 2000). Sviazi is the Russian word for connections (Efremova, 2000; Yakubovich, 2005). The use of blat or sviazi is usually accomplished through personal relationships or networks, mostly longstanding, among family members and friends, including those from the military, educational institutions, home towns, and work settings, and importantly during the Soviet period, the communist party, including the Komsomol, the communist youth league. Using blat or sviazi as a member within one’s personal network is a culturally embedded expectation. Blat or sviazi typically involves an exchange for the sake of a relationship rather than a monetary payment (Fitzpatrick, 2000; Ledeneva, 2000). Sviazi, rather than blat, has emerged as the preferred term for the practice of favors in post-Soviet business. The use of favors remains a reaction to the weak and ineffective formal institutions and the predominance of a pervasive bureaucracy (Batjargal, 2007a, b).

India: The use of Jaan-pehchaan

India’s age-old practice of जान-पहचान or its English equivalent, jaan-pehchaan or jān-pehchan, loosely translated as “you get something done through somebody you know,” is the Indian version of favors. Jaan-pehchaan has also been defined as Hindi networks affecting firm performance (Batjargal, 2007b). The Hindi word jaan or jān (जान) means “life” (Bhandwale, 2004), “to know” (McGregor, 1993; Mohanan, 1994), and “acquainted, wise, intelligent,” while the word pehchaan or pehchan (पहचान) means “recognition, identity” (Bhandwale, 2004; McGregor, 1993). Zhu et al. (2005) define jān-pehchan as “who you know” and state that it reinforces the criticality of “familiarity” and “right connections” as a means for furthering one’s business interests. They examined the dynamics of how Indian business managers value relationship building in the context of jān-pehchan or “right connections.” India’s collectivistic society favors cohesive jaan-pehchaan connections as they are developed based on criteria such as caste (varnas), gender, language, religion, sect, community, philosophy, and culture, and can create difficulties for outsiders when doing business (Schuster, 2006: 413).

China: The use of guanxi

Guanxi is a deeply rooted cultural norm in Chinese business. The term consists of two words, guan, “to close up, or do someone a favor” and xi, “to tie up, and extend long-term relationships.” Guanxi relationships are carefully developed over time and can be further categorized based on three primary kinships: chia-ren (family or kin members), shou-ren (relatives, people in same village, classmates, friends) and shreng-ren (strangers, acquaintances) (Luo, 2000, 2002). According to Fan (2002), a person possessing all variations of guanxi may be viewed differently and be treated as being of higher status. While such guanxi relationships are dynamic and change over time, there is a tendency to favor guanxi members who have family guanxi (intimate and/or blood ties) that is accompanied by greater affection (qingqing) and benevolence (ren). When establishing new business guanxi relationships, a more utility-driven, opportunistic aspect exists in creating long-term relationships (Fan, 2002). Dunfee and Warren (2001) found that few Chinese managers possess extensive business guanxi connections and thus relied upon four complex types of guanxi, in a ranked order, to achieve their long-term business relationship objectives. Chinese managers aspire to develop such strong “guanxi bases” of close-knit networks with the ultimate goal of granting numerous favors in times of bounty and seeking reciprocity in times of necessity (Michailova & Worm, 2003).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Puffer, S.M., McCarthy, D.J., Jaeger, A.M. et al. The use of favors by emerging market managers: Facilitator or inhibitor of international expansion?. Asia Pac J Manag 30, 327–349 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-012-9299-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-012-9299-3