Abstract

Data sources

Medline, The Cochrane Database Trials Register, Embase, supplemented by handsearching of five prominent periodontal journals, references from reviewed papers and contact with experts in the field of mucogingival surgery.

Study selection

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with or without a split-mouth design, on human patients. RCTs had to compare at least two different surgical interventions on clearly specified recession defects, be over six months in duration and have clearly specified clinical measurements regarding root coverage.

Data extraction and synthesis

The initial search for studies was carried out by one operator. The studies were quality assessed by two independent review authors using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. Odds Ratios were combined for dichotomous data and mean differences in continuous data using a random-effect model. The strength of the evidence of included studies was assessed according to the GRADE recommendations for bias and heterogeneity.

Results

Fifty-one RCTs were reviewed encompassing 1574 patients and 1744 recession defects. Eighty meta-analyses were conducted. Results showed that surgical intervention using a coronally advanced flap (CAF) in conjunction with a connective tissue graft (CTG) was more effective at obtaining complete root coverage (CRC), reduced recession (RecRed) and keratinised tissue (KT) gain compared to CAF alone. The use of barrier membranes with CAF showed no significant improvement to CAF alone with regard to CRC and RecRed. The use of enamel matrix derivatives (EMD) in conjunction with CAF had significant improvement in CRC, RecRed and KT gain compared to CAF alone. Using multiple techniques or biomaterials yielded similar or fewer benefits than simpler procedures

Conclusions

Treatment of recession defects is best achieved with a coronally advanced flap combined with a connective tissue graft.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

Periodontal therapy has been traditionally centred around the treatment and elimination of disease in conjunction with maintenance of a functional dentition and its surrounding tissues. Recent emphasis on aesthetic outcomes means consideration is given to a healthy, stable periodontium but also to aesthetically pleasing periodontal outcomes.1,2

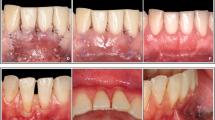

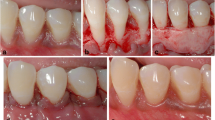

Periodontal plastic surgery (PPS) was a term first introduced by Miller in 19933 to encompass any surgical procedures used to treat or prevent abnormalities or developmental disorders of the gingiva and periodontium. Surgical techniques categorised under this term are implemented in gingival recession with the goal of achieving complete or partial root coverage to improve aesthetics, gingival health and to prevent symptoms from exposed root surfaces.4 Concordantly, treatment for gingival recession is often requested by patients.5

Various PPS interventions have been suggested as techniques to achieve complete root coverage with gingiva. Early research was provided in the late 1970s and early 1980s by Raul Caffesse and colleagues.6,7,8 Subsequently research has been conducted with traditional treatment such as the free gingival graft and lateral positioned pedicle graft techniques, to more recently developed coronally advanced or repositioned flaps.9,10,11 Coronally advanced flaps have been suggested as a clinically effective method of achieving root coverage, improved with the use of connective tissue grafting or the use of enamel matrix derivative.4

The aim of this systematic review was to update on a previous review on this topic by the same authors,4 and assess the available research on the clinical efficacy of various PPS interventions on localised gingival recession defects. This updated and expanded review covers 35 years of clinical research and includes twice the number of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and three times the number of patients in comparison to the previous review.

The review is detailed and thorough with regard to the information sources searched, the inclusion and exclusion criteria and assessment of the quality and validity of the evidence. Suitable aids were used where appropriate to grade the evidence and ensure the RCTs were of an appropriate standard. Although due emphasis was placed on the bias of the studies included, a Cochrane risk of bias table would have been useful to assess the validity of the included studies. The search terms and inclusion criteria for the evidence were narrow, which ensured there was a low degree of heterogeneity between studies, allowing for comparison and often meta-analysis of results where appropriate.

In parallel with their 2008 review the authors found the evidence supported the intervention of a coronally advanced flap, improved with the adjunct of a connective tissue graft or enamel matrix derivative, when attempting to achieve complete root coverage of recession defects. The evidence suggested that the use of multiple combinations of graft or biomaterials had no statistical improvement and often showed less improvement compared to simpler mucogingival procedures. Studies using barrier membranes, acellular dermal matrix and collagen membranes were included and assessed, but the volume of available evidence was insufficient to draw meaningful conclusions.

Although the number of patients included was provided, no social demographic information of the patients was provided. Consequently, assessment of the patients' age, gender, smoking habits, medical history and periodontal diagnosis could not be ascertained and related to the results. It is important to note that in focusing on single tooth recession defects the authors excluded any studies that assessed treatment of Miller class IV recession lesions; and therefore the conclusions made in this study may not be clinically relevant for treatment of such advanced recession defects. This may also explain the comparatively low number of studies included where one of the treatment modalities was a free gingival graft. The authors included all papers regardless of follow-up period. Only 8% of the studies reviewed had a follow-up of at least five years; unfortunately, therefore, long-term outcomes of periodontal plastic surgery could not be assessed in this review.

When considering future research, the authors suggest a review including more RCTs trialling the use of collagen matrices and enamel derivative matrices. They also suggest a review of more long-term trials, and potentially to review in more detail the aesthetic outcomes of treatment for gingival recession. Readers interested in aesthetics (in contrast to root surface coverage) should also read the recent 2016 systematic review of aesthetic outcomes following periodontal plastic surgery.12

References

Oates TW, Robinson M, Gunsolley JC . Surgical therapies for the treatment of gingival recession. A systematic review. Ann Periodontol 2003; 8: 303–320.

Kerner S, Katshain S, Sarfati A, et al. A comparison of methods of aesthetic assessment in root coverage procedures. J Clin Periodontol 2009; 36: 80–87.

Miller PD Jr . Concept of periodontal plastic surgery. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent 1993; 5: 15–20.

Cairo F, Pagliaro U, Neiri M . Treatment of gingival recession with coronally advanced flap procedures: a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol 2008; 35: 136–162.

Nieri M, Pini Prato GP, Giani M, Magnani N, Pagliaro U, Rotundo R . Patient perceptions of buccal gingival recessions and requests for treatment. J Clin Periodontol 2013; 40: 707–712.

Caffesse RG, Guinard EA . Treatment of localised gingival recessions. Part II. Coronally repositioned flap with a free gingival graft. J Periodontol 1978; 49: 357–361.

Guinard EA, Caffesse RG . Treatment of localised gingival recessions. Part III. Comparison of results obtained with lateral sliding and coronally repositioned flaps. J Periodontol 1978; 49: 457–461.

Caffesse RG, Guinard EA . Treatment of localised gingival recessions. Part IV. Results after three years. J Periodontol 1980; 51: 167–170.

Allen EP . Miller PD Jr . Coronal positioning of existing gingiva: short term results in the treatment of shallow marginal tissue recession. J Periodontol 1989; 60: 316–319.

Wennström JL, Zucchelli G . Increased gingival dimensions. A significant factor for the successful outcome of root coverage procedures? A 2-year prospective study. J Clin Periodontol 1996; 23: 770–777.

Trombelli L, Scabbia A, Wikesjö UM, Calura G . Fibrin glue application in conjunction with tetracycline root conditioning and coronally positioned flap procedure in the treatment of human gingival recession defects. J Clin Periodontol 1996; 23: 861–867.

Cairo F, Pagliaro U, Buti J, et al. Root coverage precedures improve patient aesthetics. A systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol 2016; 43: 965–975.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: Francesco Cairo Via Fra' Giovanni Angelico 51 50121 – Florence, Italy. E-mail: cairofrancesco@virgilio.it

Cairo F, Nieri M, Pagliaro U. Efficacy of periodontal plastic surgery procedures in the treatment of localized facial gingival recessions. A systematic review. J Clin Periodontol 2014; 41: S44–S62.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Madeley, E., Duane, B. Coronally advanced flap combined with connective tissue graft; treatment of choice for root coverage following recession?. Evid Based Dent 18, 6–7 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6401215

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6401215

- Springer Nature Limited