Abstract

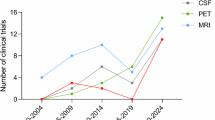

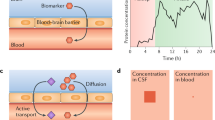

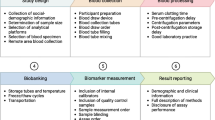

In the past 5 years, we have witnessed the first approved Alzheimer disease (AD) disease-modifying therapy and the development of blood-based biomarkers (BBMs) to aid the diagnosis of AD. For many reasons, including accessibility, invasiveness and cost, BBMs are more acceptable and feasible for patients than a lumbar puncture (for cerebrospinal fluid collection) or neuroimaging. However, many questions remain regarding how best to utilize BBMs at the population level. In this Review, we outline the factors that warrant consideration for the widespread implementation and interpretation of AD BBMs. To set the scene, we review the current use of biomarkers, including BBMs, in AD. We go on to describe the characteristics of typical patients with cognitive impairment in primary care, who often differ from the patient populations used in AD BBM research studies. We also consider factors that might affect the interpretation of BBM tests, such as comorbidities, sex and race or ethnicity. We conclude by discussing broader issues such as ethics, patient and provider preference, incidental findings and dealing with indeterminate results and imperfect accuracy in implementing BBMs at the population level.

Key points

-

Numerous studies have demonstrated the clinical utility and accuracy of plasma measures of the amyloid-β42:40 ratio and phosphorylated tau (p-tau) 181 and p-tau217 levels for the detection of Alzheimer disease (AD) pathology among clinically well-characterized patients.

-

Most AD blood-based biomarker (BBM) studies focused on specialty clinic populations are not generalizable to typical patients with dementia, and an urgent need exists to test the BBMs at the population level.

-

Chronic kidney disease, obesity and cardiovascular conditions or medication can elevate or lower AD BBM levels and need to be taken into consideration to avoid false-positive or false-negative diagnoses; understanding how to interpret AD BBM levels in the context of multiple chronic conditions is crucial for diagnosing AD among older adults in the population.

-

Other factors that might influence AD BBM levels include sex and race or ethnicity, although findings on these associations have been inconsistent to date.

-

A positive BBM test might indicate the presence of AD pathology but could be an incidental finding; the test must be considered in the context of all other symptoms and with the potential for co-pathologies.

-

Policies must be developed to protect patients who have AD BBM results added to their medical records so that they do not lose access to insurance or to disability or other rights.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.References

Prince, M. J. et al. World Alzheimer Report 2015 — the global impact of dementia: an analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. Alzheimers Dis. Int. https://www.alzint.org/u/WorldAlzheimerReport2015.pdf (2021).

GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 7, e105–e125 (2022).

McKhann, G. et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 34, 939–944 (1984).

Jack, C. R. Jr et al. NIA-AA research framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 14, 535–562 (2018).

Rabinovici, G. D. et al. Association of amyloid positron emission tomography with subsequent change in clinical management among Medicare beneficiaries with mild cognitive impairment or dementia. JAMA 321, 1286–1294 (2019).

Cummings, J. et al. Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline: 2022. Alzheimers Dement. 8, e12295 (2022).

Liu, J. L., Hlavka, J. P., Hillestad, R. & Mattke, S. Assessing the Preparedness of the U.S. Health Care System Infrastructure for an Alzheimer’s Treatment (RAND Corporation, 2017).

Mattke, S. & Hanson, M. Expected wait times for access to a disease-modifying Alzheimer’s treatment in the United States. Alzheimers Dement. 18, 1071–1074 (2022).

Sims, J. R. et al. Donanemab in early symptomatic Alzheimer disease: the TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 330, 512–527 (2023).

Lam, J., Hlávka, J. & Mattke, S. The potential emergence of disease-modifying treatments for Alzheimer disease: the role of primary care in managing the patient journey. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 32, 931–940 (2019).

Ritchie, C. W. et al. The Edinburgh Consensus: preparing for the advent of disease-modifying therapies for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 9, 85 (2017).

Paczynski, M. M. & Day, G. S. Alzheimer disease biomarkers in clinical practice: a blood-based diagnostic revolution. J. Prim. Care Community Health 13, 21501319221141178 (2022).

Sideman, A. B. et al. Primary care pracitioner perspectives on the role of primary care in dementia diagnosis and care. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e2336030 (2023).

Angioni, D. et al. Can we use blood biomarkers as entry criteria and for monitoring drug treatment effects in clinical trials? A report from the EU/US CTAD Task Force. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 10, 418–425 (2023).

Ovod, V. et al. Amyloid β concentrations and stable isotope labeling kinetics of human plasma specific to central nervous system amyloidosis. Alzheimers Dement. 13, 841–849 (2017).

Schindler, S. E. et al. High-precision plasma β-amyloid 42/40 predicts current and future brain amyloidosis. Neurology 93, e1647–e1659 (2019).

Thijssen, E. H. et al. Diagnostic value of plasma phosphorylated tau181 in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Nat. Med. 26, 387–397 (2020).

Palmqvist, S. et al. Discriminative accuracy of plasma phospho-tau217 for Alzheimer disease vs other neurodegenerative disorders. JAMA 324, 772–781 (2020).

Mielke, M. M. et al. Plasma phospho-tau181 increases with Alzheimer’s disease clinical severity and is associated with tau- and amyloid-positron emission tomography. Alzheimers Dement. 14, 989–997 (2018).

Janelidze, S. et al. Plasma p-tau181 in Alzheimer’s disease: relationship to other biomarkers, differential diagnosis, neuropathology and longitudinal progression to Alzheimer’s dementia. Nat. Med. 26, 379–386 (2020).

Mielke, M. M. et al. Performance of plasma phosphorylated tau 181 and 217 in the community. Nat. Med. 28, 1398–1405 (2022).

Janelidze, S. et al. Head-to-head comparison of 10 plasma phospho-tau assays in prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 146, 1592–1601 (2023).

Barthelemy, N. R. et al. Highly accurate blood test for Alzheimer’s disease is similar or superior to clinical cerebrospinal fluid tests. Nat. Med. 30, 1085–1095 (2024).

Hoffman, P. N. et al. Neurofilament gene expression: a major determinant of axonal caliber. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 84, 3472–3476 (1987).

Ashton, N. J. et al. A multicentre validation study of the diagnostic value of plasma neurofilament light. Nat. Commun. 12, 3400 (2021).

Mattsson, N., Cullen, N. C., Andreasson, U., Zetterberg, H. & Blennow, K. Association between longitudinal plasma neurofilament light and neurodegeneration in patients with Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 76, 791–799 (2019).

Lista, S. et al. A critical appraisal of blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 96, 102290 (2024).

Kodosaki, E., Zetterberg, H. & Heslegrave, A. Validating blood tests as a possible routine diagnostic assay of Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 23, 1153–1165 (2023).

Brand, A. L. et al. The performance of plasma amyloid beta measurements in identifying amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease: a literature review. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 14, 195 (2022).

Plassman, B. L. et al. Incidence of dementia and cognitive impairment, not dementia in the United States. Ann. Neurol. 70, 418–426 (2011).

Schubert, C. C. et al. Comorbidity profile of dementia patients in primary care: are they sicker? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 54, 104–109 (2006).

Sanderson, M. et al. Co-morbidity associated with dementia. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 17, 73–78 (2002).

Poblador-Plou, B. et al. Comorbidity of dementia: a cross-sectional study of primary care older patients. BMC Psychiatry 14, 84 (2014).

Polenick, C. A., Min, L. & Kales, H. C. Medical comorbidities of dementia: links to caregivers’ emotional difficulties and gains. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 68, 609–613 (2020).

Bunn, F. et al. Comorbidity and dementia: a scoping review of the literature. BMC Med. 12, 192 (2014).

Xu, H. et al. Kidney function, kidney function decline, and the risk of dementia in older adults: a registry-based study. Neurology 96, e2956–e2965 (2021).

Vargese, S. S. et al. Comorbidities in dementia during the last years of life: a register study of patterns and time differences in Finland. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 33, 3285–3292 (2021).

Quiñones, A. R. et al. Racial/ethnic differences in multimorbidity development and chronic disease accumulation for middle-aged adults. PLoS ONE 14, e0218462 (2019).

Kivimäki, M. et al. Association between socioeconomic status and the development of mental and physical health conditions in adulthood: a multi-cohort study. Lancet Public Health 5, e140–e149 (2020).

Wallace, L. M. K. et al. Investigation of frailty as a moderator of the relationship between neuropathology and dementia in Alzheimer’s disease: a cross-sectional analysis of data from the Rush Memory and Aging Project. Lancet Neurol. 18, 177–184 (2019).

Calvin, C. M., Conroy, M. C., Moore, S. F., Kuzma, E. & Littlejohns, T. J. Association of multimorbidity, disease clusters, and modification by genetic factors with risk of dementia. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e2232124 (2022).

Ben Hassen, C. et al. Association between age at onset of multimorbidity and incidence of dementia: 30 year follow-up in Whitehall II prospective cohort study. BMJ 376, e068005 (2022).

Hansson, O. Biomarkers for neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Med. 27, 954–963 (2021).

Syrjanen, J. A. et al. Associations of amyloid and neurodegeneration plasma biomarkers with comorbidities. Alzheimers Dement. 18, 1128–1140 (2022).

Sylvain, L. et al. Plasma phosphorylated tau 181 predicts amyloid status and conversion to dementia stage dependent on renal function. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 94, 411 (2023).

Pichet Binette, A. et al. Confounding factors of Alzheimer’s disease plasma biomarkers and their impact on clinical performance. Alzheimers Dement. 19, 1403–1414 (2023).

O’Bryant, S. E., Petersen, M., Hall, J., Johnson, L. A. & HABS-HD Study Team. Medical comorbidities and ethnicity impact plasma Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers: important considerations for clinical trials and practice. Alzheimers Dement. 19, 36–43 (2023).

Pan, F. et al. The potential impact of clinical factors on blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Transl. Neurodegener. 12, 39 (2023).

Rebelos, E. et al. Circulating neurofilament is linked with morbid obesity, renal function, and brain density. Sci. Rep. 12, 7841 (2022).

Murray, M. E. et al. Global neuropathologic severity of Alzheimer’s disease and locus coeruleus vulnerability influences plasma phosphorylated tau levels. Mol. Neurodegener. 17, 85 (2022).

Janelidze, S., Barthélemy, N. R., He, Y., Bateman, R. J. & Hansson, O. Mitigating the associations of kidney dysfunction with blood biomarkers of Alzheimer disease by using phosphorylated tau to total tau ratios. JAMA Neurol. 80, 516–522 (2023).

Zhang, B. et al. Effect of renal function on the diagnostic performance of plasma biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 15, 1150510 (2023).

Chen, X. et al. Plasma Aβ(42):Aβ(40) ratio as a biomarker for cognitive impairment in haemodialysis patients: a multicentre study. Clin. Kidney J. 16, 2129–2140 (2023).

Manouchehrinia, A. et al. Confounding effect of blood volume and body mass index on blood neurofilament light chain levels. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 7, 139–143 (2020).

Nota, M. H. C. et al. Obesity affects brain structure and function-rescue by bariatric surgery? Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 108, 646–657 (2020).

Lee, S. et al. Body mass index and two-year change of in vivo Alzheimer’s disease pathologies in cognitively normal older adults. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 15, 108 (2023).

Guo, J. et al. Body mass index trajectories preceding incident mild cognitive impairment and dementia. JAMA Psychiatry 79, 1180–1187 (2022).

Schaich, C. L., Maurer, M. S. & Nadkarni, N. K. Amyloidosis of the brain and heart: two sides of the same coin? JACC Heart Fail. 7, 129–131 (2019).

Troncone, L. et al. Aβ amyloid pathology affects the hearts of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: mind the heart. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 68, 2395–2407 (2016).

Stellos, K. et al. Association of plasma amyloid-beta (1–40) levels with incident coronary artery disease and cardiovascular mortality. Eur. Heart J. 34, P3145 (2013).

Bayes-Genis, A. et al. Bloodstream amyloid-beta (1–40) peptide, cognition, and outcomes in heart failure. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 70, 924–932 (2017).

Zhu, F. et al. Plasma amyloid-β in relation to cardiac function and risk of heart failure in general population. JACC Heart Fail. 11, 93–102 (2023).

Brum, W. S. et al. Effect of neprilysin inhibition on Alzheimer disease plasma biomarkers: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 81, 197–200 (2024).

Langenickel, T. H. et al. The effect of LCZ696 (sacubitril/valsartan) on amyloid-β concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid in healthy subjects. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 81, 878–890 (2016).

Fowler, N. R. et al. Effect of dementia on the use of drugs for secondary prevention of ischemic heart disease. J. Aging Res. 2014, 897671 (2014).

Cannon, J. A., McMurray, J. J. & Quinn, T. J. Hearts and minds’: association, causation and implication of cognitive impairment in heart failure. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 7, 22 (2015).

Keshavan, A. et al. Population-based blood screening for preclinical Alzheimer’s disease in a British birth cohort at age 70. Brain 144, 434–449 (2021).

Brickman, A. M. et al. Plasma p-tau181, p-tau217, and other blood-based Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers in a multi-ethnic, community study. Alzheimers Dement. 17, 1353–1364 (2021).

Tsiknia, A. A. et al. Sex differences in plasma p-tau181 associations with Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers, cognitive decline, and clinical progression. Mol. Psychiatry 27, 4314–4322 (2022).

Baldacci, F. et al. Age and sex impact plasma NFL and t-tau trajectories in individuals with subjective memory complaints: a 3-year follow-up study. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 12, 147 (2020).

Ramanan, V. K. et al. Association of plasma biomarkers of Alzheimer disease with cognition and medical comorbidities in a biracial cohort. Neurology 101, e1402–e1411 (2023).

Lussier, F. Z. et al. Plasma levels of phosphorylated tau 181 are associated with cerebral metabolic dysfunction in cognitively impaired and amyloid-positive individuals. Brain Commun. 3, fcab073 (2021).

Saloner, R. et al. Plasma phosphorylated tau-217 exhibits sex-specific prognostication of cognitive decline and brain atrophy in cognitively unimpaired adults. Alzheimers Dement. 20, 376–387 (2024).

Vila-Castelar, C. et al. Sex differences in blood biomarkers and cognitive performance in individuals with autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 19, 4127–4138 (2023).

Rajan, K. B. et al. Population estimate of people with clinical Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment in the United States (2020–2060). Alzheimers Dement. 17, 1966–1975 (2021).

Matthews, K. A. et al. Racial and ethnic estimates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in the United States (2015–2060) in adults aged ≥65 years. Alzheimers Dement. 15, 17–24 (2019).

Schindler, S. E. et al. Effect of race on prediction of brain amyloidosis by plasma Aβ42/Aβ40, phosphorylated tau, and neurofilament light. Neurology 99, e245–e257 (2022).

Morris, J. C. et al. Assessment of racial disparities in biomarkers for Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 76, 264–273 (2019).

Wilkins, C. H. et al. Racial and ethnic differences in amyloid PET positivity in individuals with mild cognitive impairment or dementia: a secondary analysis of the Imaging Dementia-Evidence for Amyloid Scanning (IDEAS) cohort study. JAMA Neurol. 79, 1139–1147 (2022).

Garrett, S. L. et al. Racial disparity in cerebrospinal fluid amyloid and tau biomarkers and associated cutoffs for mild cognitive impairment. JAMA Netw. Open 2, e1917363 (2019).

Raman, R. et al. Disparities by race and ethnicity among adults recruited for a preclinical Alzheimer disease trial. JAMA Netw. Open 4, e2114364 (2021).

Hajjar, I. et al. Association of plasma and cerebrospinal fluid Alzheimer disease biomarkers with race and the role of genetic ancestry, vascular comorbidities, and neighborhood factors. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e2235068 (2022).

Hall, J. R., Petersen, M., Johnson, L. & O’Bryant, S. E. Characterizing plasma biomarkers of Alzheimer’s in a diverse community-based cohort: a cross-sectional study of the HAB-HD cohort. Front. Neurol. 13, 871947 (2022).

Gleason, C. E. et al. Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers in Black and non-Hispanic White cohorts: a contextualized review of the evidence. Alzheimers Dement. 18, 1545–1564 (2022).

Barnes, L. L. Alzheimer disease in African American individuals: increased incidence or not enough data? Nat. Rev. Neurol. 18, 56–62 (2022).

Simons, R. L. et al. Racial discrimination during middle age predicts higher serum phosphorylated tau and neurofilament light chain levels a decade later: a study of aging black Americans. Alzheimers Dement. 20, 3485–3494 (2024).

Cholerton, B. et al. Total brain and hippocampal volumes and cognition in older American Indians: the Strong Heart Study. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 31, 94–100 (2017).

Granot-Hershkovitz, E. et al. APOE alleles’ association with cognitive function differs across Hispanic/Latino groups and genetic ancestry in the study of Latinos — investigation of neurocognitive aging (HCHS/SOL). Alzheimers Dement. 17, 466–474 (2021).

Hansson, O. et al. The Alzheimer’s Association appropriate use recommendations for blood biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 18, 2669–2686 (2022).

Drabo, E. F. et al. Longitudinal analysis of dementia diagnosis and specialty care among racially diverse Medicare beneficiaries. Alzheimers Dement. 15, 1402–1411 (2019).

Boustani, M. et al. Who refuses the diagnostic assessment for dementia in primary care? Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 21, 556–563 (2006).

McCarten, J. R., Anderson, P., Kuskowski, M. A., McPherson, S. E. & Borson, S. Screening for cognitive impairment in an elderly veteran population: acceptability and results using different versions of the Mini-Cog. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 59, 309–313 (2011).

Balogun, W. G., Zetterberg, H., Blennow, K. & Karikari, T. K. Plasma biomarkers for neurodegenerative disorders: ready for prime time? Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 36, 112–118 (2023).

Brum, W. S. et al. A two-step workflow based on plasma p-tau217 to screen for amyloid beta positivity with further confirmatory testing only in uncertain cases. Nat. Aging 3, 1079–1090 (2023).

Verberk, I. M. W. et al. Characterization of pre-analytical sample handling effects on a panel of Alzheimer’s disease-related blood-based biomarkers: results from the Standardization of Alzheimer’s Blood Biomarkers (SABB) working group. Alzheimers Dement. 18, 1484–1497 (2022).

Hampel, H. et al. Blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease: current state and future use in a transformed global healthcare landscape. Neuron 111, 2781–2799 (2023).

Morgan, D. J. et al. Accuracy of practitioner estimates of probability of diagnosis before and after testing. JAMA Intern. Med. 181, 747–755 (2021).

Kapasi, A., DeCarli, C. & Schneider, J. A. Impact of multiple pathologies on the threshold for clinically overt dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 134, 171–186 (2017).

Galasko, D. R., Grill, J. D., Lingler, J. H. & Heidebrink, J. L. A blood test for Alzheimer’s disease: it’s about time or not ready for prime time? J. Alzheimers Dis. 90, 963–966 (2022).

Howe, E. G. Ethical issues in diagnosing and treating Alzheimer disease. Psychiatry 3, 43–53 (2006).

Frederiksen, K. S. et al. European Academy of Neurology/European Alzheimer’s Disease Consortium position statement on diagnostic disclosure, biomarker counseling, and management of patients with mild cognitive impairment. Eur. J. Neurol. 28, 2147–2155 (2021).

Arias, J. J., Manchester, M. & Lah, J. Direct to consumer biomarker testing for Alzheimer disease — are we ready for the insurance consequences? JAMA Neurol. 81, 107–108 (2024).

Mattsson, N., Brax, D. & Zetterberg, H. To know or not to know: ethical issues related to early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2010, 841941 (2010).

Philip, G., Savundranayagam, M. Y., Kothari, A. & Orange, J. B. Exploring stigmatizing perceptions of dementia among racialized groups living in the Anglosphere: a scoping review. Aging Health Res. 4, 100170 (2024).

Walker, J. et al. Patient and caregiver experiences of living with dementia in Tanzania. Dementia 22, 1900–1920 (2023).

Werner, P. & Kim, S. A cross-national study of dementia stigma among the general public in Israel and Australia. J. Alzheimers Dis. 83, 103–110 (2021).

Stites, S. D. et al. How reactions to a brain scan result differ for adults based on self-identified Black and White race. Alzheimer’s Dement. 20, 1527–1537 (2024).

Stites, S. D. et al. The relative contributions of biomarkers, disease modifying treatment, and dementia severity to Alzheimer’s stigma: a vignette-based experiment. Soc. Sci. Med. 292, 114620 (2022).

Grill, J. D. et al. Short-term psychological outcomes of disclosing amyloid imaging results to research participants who do not have cognitive impairment. JAMA Neurol. 77, 1504–1513 (2020).

van der Schaar, J. et al. Considerations regarding a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease before dementia: a systematic review. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 14, 31 (2022).

Jack, C. R. Jr. et al. Age-specific and sex-specific prevalence of cerebral β-amyloidosis, tauopathy, and neurodegeneration in cognitively unimpaired individuals aged 50–95 years: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 16, 435–444 (2017).

Ossenkoppele, R. et al. Amyloid and tau PET-positive cognitively unimpaired individuals are at high risk for future cognitive decline. Nat. Med. 28, 2381–2387 (2022).

Bennett, D. A. et al. Neuropathology of older persons without cognitive impairment from two community-based studies. Neurology 66, 1837–1844 (2006).

Dodge, H. H. et al. Risk of incident clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease-type dementia attributable to pathology-confirmed vascular disease. Alzheimers Dement. 13, 613–623 (2017).

Stites, S. D., Milne, R. & Karlawish, J. Advances in Alzheimer’s imaging are changing the experience of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 10, 285–300 (2018).

Xanthopoulou, P. & McCabe, R. Subjective experiences of cognitive decline and receiving a diagnosis of dementia: qualitative interviews with people recently diagnosed in memory clinics in the UK. BMJ Open 9, e026071 (2019).

Planche, V. et al. Validity and performance of blood biomarkers for Alzheimer disease to predict dementia risk in a large clinic-based cohort. Neurology 100, e473–e484 (2023).

Mattsson-Carlgren, N. et al. Prediction of longitudinal cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer disease using plasma biomarkers. JAMA Neurol. 80, 360–369 (2023).

Largent, E. A., Stites, S. D., Harkins, K. & Karlawish, J. That would be dreadful: the ethical, legal, and social challenges of sharing your Alzheimer’s disease biomarker and genetic testing results with others. J. Law Biosci. 8, lsab004 (2021).

Acknowledgements

M.M.M. and N.R.F. acknowledge support from the National Institute on Aging and the NIH (grants U24 AG082930, RF1 AG077386, RF1 AG079397, RF1 AG69052 and P30 AG07247).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M.M. researched data for the article and wrote the article. Both authors contributed substantially to discussion of the content and reviewed and/or edited the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.M.M. has served on scientific advisory boards and/or has consulted for Acadia, Biogen, Eisai, LabCorp, Lilly, Merck, PeerView Institute, Novo Nordisk, Roche, Siemens Healthineers and Sunbird Bio. N.R.F. declares no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Neurology thanks J. Schott, C. Gleason and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Mielke, M.M., Fowler, N.R. Alzheimer disease blood biomarkers: considerations for population-level use. Nat Rev Neurol 20, 495–504 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-024-00989-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-024-00989-1

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Navigating the Landscape of Plasma Biomarkers in Alzheimer's Disease: Focus on Past, Present, and Future Clinical Applications

Neurology and Therapy (2024)

-

Rationale and design of the BeyeOMARKER study: prospective evaluation of blood- and eye-based biomarkers for early detection of Alzheimer’s disease pathology in the eye clinic

Alzheimer's Research & Therapy (2024)