Abstract

Despite evidence strongly supporting use of non-invasive or minimally invasive procedures in caries management, there is still a large gap between evidence-based recommendations and application of these concepts in practice, with the practice of dentistry still largely dominated by invasive procedures in the US. This paper describes efforts in education and clinical practice in the US in the last decade to promote evidence-based cariology strategies, which support a minimum intervention dentistry (MID) philosophy. These include, for example: a competency-based core cariology curriculum framework which has been developed and disseminated. National education accreditation standards supporting caries management are likely to soon be changed to support assessment of best evidence in cariology. There are several ongoing efforts by organised dentistry and other groups involving dental educators, researchers and clinical practitioners to promote cariology concepts in practice, such as the development of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for caries management by the American Dental Association. Within each of these strategies there are challenges, but also opportunities to expand the implementation of MID in the US, which create optimism for future improvements over time.

Key points

-

Even though multiple challenges exist to changing the paradigm of care as it relates to caries management in the US, there are also multiple opportunities to promote MID strategies within cariology education and practice

-

Collaborative efforts have led to the development and implementation of a core cariology curriculum framework in the US that promotes principles of MID.

-

Several organisations have developed or updated evidence-based guidelines for caries interventions, including the development of guidelines for non-restorative management of cavitated and non-cavitated lesions by the American Dental Association, which promotes principles of MID.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite evidence strongly supporting use of non-invasive therapies1,2,3 or minimally invasive procedures,3,4 within a comprehensive disease management plan at the tooth and individual level, evidence from the US5,6,7,8 and worldwide9,10,11 indicates that there is still a large gap between evidence-based recommendations and how dentists apply updated concepts. One of the main challenges of implementing a minimum intervention dentistry (MID) philosophy is an old and recalcitrant model of care, still very pervasive in practice, in which management of the caries disease process is accomplished primarily by removal of all demineralised tissue (regardless of depth, texture, etc), followed by restoration of teeth (that is, the traditional surgical or restorative model), and based in a conceptualisation of dental caries as an infectious and transmissible disease.12 However, the understanding of the disease and how best to manage it has evolved as evidence has changed, and an up-to-date understanding is essential to achieve best prevention and management outcomes.10,13 Currently, dental caries is defined as a biofilm-mediated, diet modulated, multifactorial, non-communicable, dynamic disease process caused by an ecological dysbiosis between the host and oral biofilms, that results in dental mineral loss over time.14,15,16,17,18,19 In fact, the disease and the resulting caries lesions are influenced by biological, behavioural, psychosocial, and environmental factors at the individual, family and community level, affecting decisions on how to prevent and manage it.18,19,20

Current understanding of the caries process supports the use of minimally invasive dentistry (MID) approaches to be implemented whenever possible,21,22 conserving tooth structure and preserving pulpal health.23 However, a systematic review indicates that thresholds on when to restore or not restore caries lesions have not improved over time.11 Studies assessing clinical decision making by US dental practitioners who are part of a national dental practice-based research network indicate a large variation in the restorative decision-making process.5,6,7 Unfortunately, the compiled evidence from existing surveys suggests that many US dentists surgically treat caries lesions prematurely, especially when working in private solo practices compared to large groups practices.6 A survey of US practitioners also suggests that complete caries removal to hard dentine is very common in practice, and that pulp diagnostic tests are not used routinely before decisions for treatment of teeth with deep caries lesions.24 This should come as no surprise, as there is a wide range of teaching practices related to caries removal among US dental schools.25 There is also evidence suggesting a lack of implementation of individualised caries preventive approaches.8 In fact, a considerable number of dentists do not routinely perform a caries risk assessment (CRA),8 or not in all patients,26 which has been advocated for management of dental caries.27 For those who perform CRA, there is not a strong association between the results of the CRA and individualised preventive regimens for adult patients.8 All these findings suggest that an invasive and not individualised approach to caries management is common, which may have been influenced by the fact that competency associated with caries management has been focused primarily on assessing restoration of teeth as part of the accreditation standards for dental training in the US, and the fact that many licensing exams still expect removal of carious tissues to hard dentine. The lack of high-level evidence for non-invasive or minimally invasive therapies in US populations has also compounded the implementation of many of these concepts.

Fortunately, there are many actions and ongoing efforts among dental educators, researchers, and by organised dentistry in the US promoting best evidence-based strategies in cariology, including MID principles. Examples of these efforts, and associated opportunities and challenges are described next.

Development of a core cariology curriculum framework in the US

Dental education can play an influential role to expand the MID philosophy into dental practice. The treatment philosophy inculcated in dental school, particularly during clinical experiences, has a great potential to impact a graduating dentist's decision-making process, especially whether to be more or less invasive in caries control.28 There is a world-wide need for integrating new concepts of dental caries disease and its management in the curriculum of dental schools around the globe29,30,31,32 including the US.33 Many US dental schools formally include preventive dentistry as part of their curriculum;34 however, despite several improvements in caries management over the last decades,9,35 many cariology programmes lack the profundity expected for this important area of clinical dentistry.36 A survey of cariology teaching in the US37 showed that 31% of dental schools did not have a defined curriculum for cariology; 51% of schools had more than one department in their institution that was primarily responsible for teaching cariology; and there was great variability in thresholds taught for restorative intervention (for example, 7% of schools were teaching to restore caries lesions when they were radiographically only in enamel). The survey also found that 35% of schools thought didactic teachings were not well translated into clinic, while 30% were unsure.37 In addition, there is a misalignment between what is required in some regional board live patient exams and what is taught in the curriculum of many schools, and this has been identified as a further barrier for MID implementation.37

To address these needs, and because cariology did not have a strong place in curriculum development and in competency assessment in US dental education,9 the section on cariology of the American Dental Education Association (ADEA) organised in 2015 a consensus workshop to adapt the European Core Cariology Curriculum32 to US dental education.33 The group developed a competency-based core cariology curriculum (CCC) framework for use in US dental schools, based on best available evidence. The CCC includes five domains: 1. knowledge base; 2. risk assessment, diagnosis, and synthesis; 3. treatment decision making: preventive strategies and nonsurgical management; 4. treatment decision making: surgical therapy; and 5. evidence-based cariology in clinical and public practice, each one accompanied by objectives and learning outcomes adapted to the US. The curriculum framework also includes a recommended caries management competency statement. The goal of the CCC is to provide a uniform but flexible platform for what should be included and assessed in US dental schools, with information schools can adapt to their own teaching and assessment structure.

As this curriculum framework is adapted and implemented by each dental school, there is a need to determine how best to assess the expected learning outcomes.33 Thus, different ways of teaching and assessment are likely needed, especially if schools are to follow the current accreditation standards for US dental education38 which emphasise critical thinking and problem solving during the teaching/learning process.

It is essential that other members of the dental workforce are included in these cariology curriculum discussions. For example, dental hygienists are a very important component of the dental workforce in the US, and critical to promote principles of MID in caries prevention and management. Dental hygienists should get robust training in cariology to exert their essential role, both at the individual and community level. There is an ongoing initiative to develop a core cariology curriculum framework for dental hygienists in the nation, similar to what was done for dental schools.33

Promotion of evidence-based caries management strategies in education and practice

Several groups have been created in the US in the last decade to promote and call attention to cariology in education, practice and research. Many of these groups work closely with international groups (for example, European Organisation for Caries Research [ORCA], International Association for Dental Research [IADR]) and efforts (for example, Caries Care International []). Some examples are briefly presented next to illustrate the importance and recognition that cariology, including principles of MID, is receiving nationally.

-

Over a decade ago the ADEA approved the formation of a cariology section to help promote cariology within US dental education. The CCC framework in the US is an example of the work by this group

-

The Caries Management by Risk Assessment (CAMBRA) movement aims to promote a risk-based approach to caries management, highlighting the need to individualise care. Regional CAMBRA meetings have been held in the US for years, including the west coast, central region, east coast, and more recently southern portions of the US, leading recently to national meetings around caries management. These regional and national CAMBRA coalitions involve groups of schools and other interested parties. Numerous efforts to reach dentists in private practice by holding continuing education meetings have been advocated by these groups

-

The American Academy of Cariology (AAC; aacariology.org) was established in 2016 to address the gap between the evidence-based and actual treatment/management of dental caries in the US. Other healthcare providers such as physicians and nurses, and teachers, social workers, and similar professionals are also encouraged to engage in the AAC mission. Although the AAC is a very young organisation, it has submitted a request for an important change in accreditation standard 2-24 established by the Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA). The change is expected to be approved and includes caries management as part of the clinical competencies that must be demonstrated before graduation. This should further encourage the implementation of the CCC framework33

-

In 2015, the Alliance for a Cavity Free Future (ACFF) established a Canada-US Chapter (). The group has strongly focused on promoting interdisciplinary efforts for caries control in children. In fact, in 2019 the ACFF together with the AAC, the cariology section of ADEA and the European Organisation for Caries Research (ORCA), organised a conference focused on discussing challenges and opportunities for the implementation of evidence-based caries management strategies in dental practice and academia, with a publication from these deliberations expected soon. The ACFF also has provided funding for interprofessional efforts to improve caries outcomes in the US and Canada.

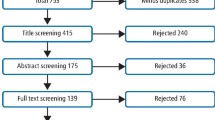

In addition to the efforts from these different organisations and groups, there are also several ongoing activities led by organised dentistry. For example, the American Dental Association (ADA) has established a plan to develop an overall evidence-based guideline for making clinical decisions at each stage of the caries process. Given the magnitude of the effort, the task has been broken up into the development of four guidelines, that will ultimately be connected into a larger overall guide.39 The first of these evidence-based clinical practice guidelines focused on nonrestorative treatments for carious lesions,40 both for primary and permanent teeth, by surface, and it is based on a systematic review with network metanalysis.1 Other guidelines in the series will include caries prevention (currently under development), restorative treatments for caries lesions (currently under development), and caries lesion detection and diagnosis (not started yet). Those are programmed to be released in oncoming years. The evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for nonrestorative treatments40 highlight that several nonrestorative approaches are effective in arresting or reversing carious lesions in permanent and primary teeth, stressing that for non-cavitated lesions 'non-restorative interventions should be prioritised based on effectiveness, safety, and feasibility'.40

Challenges and opportunities to promote MI strategies within cariology in the US

All of the efforts described previously provide a high level of optimism that best evidence in cariology, including principles of MID, will result in changes in the practice of dentistry in the US in the decades to come. However, there are numerous factors that offer a challenge and that need to be addressed to facilitate implementation in education and practice.41 Some of these can be considered as internal (that is, inside every institution), while some are more external (for example, healthcare system). Some examples are provided next.

Internal implementation factors to be considered in order to facilitate success:33

-

In education, a well-defined cariology curriculum, effectively integrating didactic, preclinical and clinical teaching components

-

A dental health record that supports charting and monitoring of caries lesion severity and activity, and use of caries risk assessment protocols with individualised risk-based re-assessments

-

Clinician/faculty active training and calibration programmes, including effective communication between faculty, especially in schools where various departments are responsible for the educational process on caries management. Variations on faculty education can directly impact cariology teaching.30,33 Faculty calibration sessions, for example, have been demonstrated to improve the standardisation in the use of CRA.42,43 Furthermore, having guidelines for implementation, facilitate the use of CRA by both faculty and students44

-

Outcomes assessment (productivity): give value ('reward' or reimbursement) for clinical time spent performing diagnosis and nonrestorative and conservative management of dental caries, as we reward treating caries lesions restoratively

-

Use of diagnostic and risk-based codes to facilitate tracking and assessment of these interventions.

External implementation factors that could challenge implementation of best evidence in cariology and MID include perceived or existing standards of care, the existing healthcare system, issues associated with appropriate use of information technology, public expectations of treatments and outcomes, etc. Out of these, many consider lack of economic incentives for non-invasive or minimally invasive procedures as one of the largest barriers to implement MID cariology approaches, as revenue is dependent on the type of procedures performed, and not the successful chronic management of the disease process.6

Many dentists do not manage dental caries using the latest evidence available, and some reserach suggests that dentists who do not perform CRA or diet counselling regularly tend to be more invasive.45 Attending continuing education courses is encouraged to get up-to-date evidence-based recommendations and clinical practice guidelines for caries management.40,46,47 Creation of procedural technique protocols48 could also be useful in the transition from a more traditional and invasive restorative philosophy to a MID philosophy. At the same time, better evidence and validation supporting CRA tools along with guidelines on how best to incorporate validated CRA tools into practice are needed.41

The challenges discussed previously offer opportunities for improvement. In the US, conservative approaches for caries management are being implemented, albeit with much room for improvement. For example, a study published in 2013 showed that atraumatic restorative therapy appears to be underused in paediatric dentistry residency programmes in the US.49 There is a lack of knowledge by general dentists about silver diamine fluoride (SDF),50 which became available in the US several years ago, and was introduced with good evidence supporting its use for caries management being popular among paediatric dentists and dental hygienists.50,51 Participation in organisations such as practice-based research networks may expedite the translation of research into practice.52 A recent cross-sectional study53 conducted in the US suggested that dentists in public-health practices are embracing the MID philosophy and conservative evidence-based caries management protocols more readily than other groups. Increasing the diffusion of evidence to the public about the broad advantages of a MID philosophy might improve the translation of evidence into practice.54 For example, a patient who thinks that only professional dental cleanings and restorations protect and fix their dentition would never assume their individual responsibility for caries management. Improving the health literacy of individuals and communities is essential to improve their health.

Conclusions

US dental educators have taken the responsibility to engage and promote best evidence in cariology, including principles of the MID philosophy. A competency-based core cariology curriculum framework has been developed and disseminated. The accreditation standard for caries management in US dental education is very likely to soon be changed to better support assessment of best evidence in cariology as it relates to caries detection, diagnosis, risk assessment and nonrestorative and restorative caries management, supporting the MID philosophy.

The MID philosophy is being used by more dentists than ever before in the US and it will continue to increase. There are several ongoing efforts by organised dentistry and other groups involving dental educators, researchers and clinical practitioners. The creation of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for caries management in the US should promote the MID philosophy nationally.

References

Urquhart O, Tampi M P, Pilcher L et al. Nonrestorative Treatments for Caries: Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. J Dent Res 2019; 98: 14-26.

Marinho V C, Worthington H V, Walsh T, Clarkson J E. Fluoride varnishes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 7, DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002279.pub2.

Dorri M, Dunne S M, Walsh T, Schwendicke F. Micro-invasive interventions for managing proximal dental decay in primary and permanent teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010431.pub2.

Ahovuo-Saloranta A, Forss H, Walsh T, Nordblad A, Makela M, Worthington H V. Pit and fissure sealants for preventing dental decay in permanent teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 7: DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001830.pub5.

Gordan V V, Garvan C W, Heft M W et al. Restorative treatment thresholds for interproximal primary caries based on radiographic images: findings from the Dental Practice-Based Research Network. Gen Dent 2009; 57: 654-663.

Gordan V V, Bader J D, Garvan C W et al. Restorative treatment thresholds for occlusal primary caries among dentists in the dental practice-based research network. J Am Dent Assoc 2010; 141: 171-184.

Rechmann P, Domejean S, Rechmann B M, Kinsel R, Featherstone J D. Approximal and occlusal carious lesions: Restorative treatment decisions by California dentists. J Am Dent Assoc 2016; 147: 328-338.

Riley J L 3rd, Gordan V V, Ajmo C T et al. Dentists' use of caries risk assessment and individualized caries prevention for their adult patients: findings from The Dental Practice-Based Research Network. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2011; 39: 564-573.

Fontana M, Zero D. Bridging the gap in caries management between research and practice through education: the Indiana University experience. J Dent Educ 2007; 71: 579-591.

Schwendicke F, Foster Page L A, Smith L A, Fontana M, Thomson W M, Baker S R. To fill or not to fill: a qualitative cross-country study on dentists' decisions in managing non-cavitated proximal caries lesions. Implement Sci 2018; 13: 54.

Innes N P T, Schwendicke F. Restorative Thresholds for Carious Lesions: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Dent Res 2017; 96: 501-508.

Tanzer J M. Dental caries is a transmissible infectious disease: the Keyes and Fitzgerald revolution. J Dent Res 1995; 74: 1536-1542.

Fernández C E, Chanin M, Culver A M, Stein A, Appice G. Conceptualization of Dental Caries by Dental Students and Its Relationship with Preventive Oral Care Routine. J Dent Educ. 2020. doi: 10.1002/jdd.12357. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32805773.

Pitts N B, Zero D T, Marsh P D et al. Dental caries. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017; 3: DOI: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.30.

Simon-Soro A, Mira A. Solving the aetiology of dental caries. Trends Microbiol 2015; 23: 76-82.

Philip N, Suneja B, Walsh L. Beyond Streptococcus mutans: clinical implications of the evolving dental caries aetiological paradigms and its associated microbiome. Br Dent J 2018; 224: 219-225.

Marsh P D. The commensal microbiota and the development of human disease - an introduction. J Oral Microbiol 2015; 7: DOI: 10.3402/jom.v7.29128.

Fejerskov O. Changing paradigms in concepts on dental caries: consequences for oral health care. Caries Res 2004; 38: 182-191.

Machiulskiene V, Campus G, Carvalho J C et al. Terminology of Dental Caries and Dental Caries Management: Consensus Report of a Workshop Organized by ORCA and Cariology Research Group of IADR. Caries Res 2019; 54: 7-14.

Fejerskov O, Nyvad B, Kidd E A M. Dental caries: what it is? In O Fejerskov, B Nyvad and EAM Kidd (editors) Dental Caries The Disease and its Clinical Management, 3rd ed, 7-10. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, 2015.

Machiulskiene V, Carvalho J C. Clinical Diagnosis of Dental Caries in the 21st Century: Introductory Paper - ORCA Saturday Afternoon Symposium, 2016. Caries Res 2018; 52: 387-391.

Carvalho J C, Dige I, Machiulskiene V et al. Occlusal Caries: Biological Approach for Its Diagnosis and Management. Caries Res 2016; 50: 527-542.

Schwendicke F, Frencken J E, Bjorndal L et al. Managing Carious Lesions: Consensus Recommendations on Carious Tissue Removal. Adv Dent Res 2016; 28: 58-67.

Koopaeei M M, Inglehart M R, McDonald N, Fontana M. General dentists', paediatric dentists', and endodontists' diagnostic assessment and treatment strategies for deep carious lesions: A comparative analysis. J Am Dent Assoc 2017; 148: 64-74.

Nascimento M M, Behar-Horenstein L S, Feng X, Guzman-Armstrong S, Fontana M. Exploring How U S. Dental Schools Teach Removal of Carious Tissues During Cavity Preparations. J Dent Educ 2017; 81: 5-13.

Norton W E, Funkhouser E, Makhija S K et al. Concordance between clinical practice and published evidence: findings from The National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Am Dent Assoc 2014; 145: 22-31.

Young D A, Featherstone J D. Caries management by risk assessment. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2013; 41: e53-e63.

Dowell T B, Holloway P J, Keshani D, Clerehugh V. Do dentists fill teeth unnecessarily? Br Dent J 1983; 155: 247-249.

Martignon S, Gomez J, Tellez M, Ruiz J A, Marin L M, Rangel M C. Current cariology education in dental schools in Spanish-speaking Latin American countries. J Dent Educ 2013; 77: 1330-1337.

Tikhonova S, Girard F, Fontana M. Cariology Education in Canadian Dental Schools: Where Are We? Where Do We Need to Go? J Dent Educ 2018; 82: 39-46.

Ferreira-Nobilo N P, Rosario de Sousa M, L, Cury J A. Cariology in curriculum of Brazilian dental schools. Braz Dent J 2014; 25: 265-270.

Schulte A G, Pitts N B, Huysmans M C, Splieth C, Buchalla W. European Core Curriculum in Cariology for undergraduate dental students. Eur J Dent Educ 2011; 15 Suppl 1: 9-17.

Fontana M, Guzman-Armstrong S, Schenkel A B et al. Development of a Core Curriculum Framework in Cariology for U S. Dental Schools. J Dent Educ 2016; 80: 705-720.

Brown J P. A new curriculum framework for clinical prevention and population health, with a review of clinical caries prevention teaching in U S, Canadian dental schools. J Dent Educ 2007; 71: 572-578.

Yorty J S, Walls A T, Wearden S. Caries risk assessment/treatment programmes in U S. dental schools: an eleven-year follow-up. J Dent Educ 2011; 75: 62-67.

Clark T D, Mjor I A. Current teaching of cariology in North American dental schools. Oper Dent 2001; 26: 412-418.

Fontana M, Horlak D, Sharples S, Wolff M, Young D. Teaching of cariology in U S. dental schools. AADR Annual Meeting, 2012.

CODA. Commission on Dental Accreditation. Accreditation standards for dental education programmes. 2016. Available at (accesed March 2020).

Fontana M, Pilcher L, Tampi M P et al. Caries management for the modern age: Improving practice one guideline at a time. J Am Dent Assoc 2018; 149: 935-937.

Slayton R L, Urquhart O, Araujo M W B et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline on nonrestorative treatments for carious lesions: A report from the American Dental Association. J Am Dent Assoc 2018; 149: 837-849

Fontana M, Wolff M. Translating the caries management paradigm into practice: challenges and opportunities. J Calif Dent Assoc 2011; 39: 702-708.

Goolsby S P, Young D A, Chiang H K, Carrico C K, Jackson L V, Rechmann P. The Effects of Faculty Calibration on Caries Risk Assessment and Quality Assurance. J Dent Educ 2016; 80: 1294-1300.

Rechmann P, Featherstone J D. Quality assurance study of caries risk assessment performance by clinical faculty members in a school of dentistry. J Dent Educ 2014; 78: 1331-1338.

Young D A, Alvear Fa B, Rogers N, Rechmann P. The Effect of Calibration on Caries Risk Assessment Performance by Students and Clinical Faculty. J Dent Educ 2017; 81: 667-674.

Kakudate N, Sumida F, Matsumoto Y et al. Restorative treatment thresholds for proximal caries in dental PBRN. J Dent Res 2012; 91: 1202-1208.

Young D A, Kutsch V K, Whitehouse J. A clinician's guide to CAMBRA: a simple approach. Compend Contin Educ Dent 2009; 30: 92-94, 96, 98.

Wright J T, Crall J J, Fontana M et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline for the use of pitandfissure sealants: A report of the American Dental Association and the American Academy of Paediatric Dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc 2016; 147: 672-682.

Illinois Department of Public Health. Public Health Intervention: Use of Silver Diamine Fluoride for Arresting Dental Caries. 2017. Available at (accessed Nov 2017).

Kateeb E, Warren J, Damiano P et al. Atraumatic Restorative Treatment (ART) in paediatric dentistry residency programmes: a survey of programme directors. Paediatr Dent 2013; 35: 500-505.

Antonioni M B, Fontana M, Salzmann L B, Inglehart M R. Paediatric Dentists' Silver Diamine Fluoride Education, Knowledge, Attitudes, and Professional Behaviour: A National Survey. J Dent Educ 2019; 83: 173-182.

Chhokar S K, Laughter L, Rowe D J. Perceptions of Registered Dental Hygienists in Alternative Practice Regarding Silver Diamine Fluoride. J Dent Hyg 2017; 91: 53-60.

Rindal D B, Flottemesch T J, Durand E U et al. Practice change toward better adherence to evidence-based treatment of early dental decay in the National Dental PBRN. Implement Sci 2014; 9: 177.

Oliveira D C, Warren J J, Levy S M, Kolker J, Qian F, Carey C. Acceptance of Minimally Invasive Dentistry Among US Dentists in Public Health Practices. Oral Health Prev Dent 2016; 14: 501-508.

Schwendicke F, Domejean S, Ricketts D, Peters M. Managing caries: the need to close the gap between the evidence base and current practice. Br Dent J 2015; 219: 433-438.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

CEF is coordinator of the cariology unit, at the University of Talca, Chile, and declares to have no commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. MF is past chair and councillor of the ADEA cariology section, current co-chair of the Canada-US section of ACFF, current chair of AAC, and clinical co-director of cariology at the University of Michigan School of Dentistry. CG is co-director of cariology at the University of Michigan School of Dentistry.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fernández, C., González-Cabezas, C. & Fontana, M. Minimum intervention dentistry in the US: an update from a cariology perspective. Br Dent J 229, 483–486 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-020-2219-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-020-2219-x

- Springer Nature Limited